Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

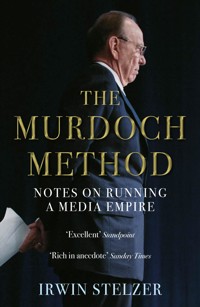

An exclusive, insider viewpoint on the "Murdoch Method" from his right-hand man and adviser, Irwin Stelzer. Rupert Murdoch is one of the most notorious and successful businessmen of our age. Now, for the first time, an insider within the Murdoch empire reveals the formidable method behind the man. Irwin Stelzer, an adviser to Murdoch for 35 years reveals what makes Rupert tick and how he grew from humble beginnings as the owner of an Adelaide newspaper, to becoming the head of a globe-circling enterprise worth over $50 billion. But this isn't just a straight-forward business memoir. Rather, Stelzer explores what makes Murdoch so unique: whether that be down to his love of taking risks, his mistrust of the establishment, or his unconventional management style. Revealing what really happened during Murdoch's most infamous moments, Stelzer examines how Murdoch navigated both his success and his failures: including his tussles with regulators, his doomed foray into social media, his victories over trade unions, and how he handled the fallout of the News of the World phone-hacking scandal. Venerated, despised, admired and mistrusted, Murdoch has left an indelible imprint on the world of business, media, and politics. Read this engrossing account to find out how he did it.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 511

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FORTHE MURDOCH METHOD

‘A finely balanced assessment of the media mogul’s sprawling empire – written by his right-hand man.’

Guardian

‘Want to be a newspaper proprietor? A movie mogul? An icon? Irwin Stelzer’s inside knowledge shows us how it’s done.’

Baron Maurice Saatchi, co-founder, Saatchi & Saatchi

‘Instructive and entertaining… It takes the independence and acuity of a friend – and at the same time an arm’s-length adviser of someone of Irwin Stelzer’s standing – to convey brilliantly an analysis of the risks that Murdoch has taken on the road to success.’

Lord Salisbury, former Leader of the House of Lords

‘A fascinating account of the organisational approach [Murdoch] utilised in building a great entrepreneurial media empire.’

John Malone, chairman of Liberty Media

‘The author’s close relationship with Rupert Murdoch gave him his biggest advantage as a biographer – special insights into the man and his motives.’

David Green, chief executive of Civitas

First published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This edition published in 2019.

Copyright © Irwin Stelzer, 2018

The moral right of Irwin Stelzer to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 401 6

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 402 3

Printed in Great Britain

Credits for photo insert: plates 1, 3, 6, 8, 10, 11, 14 © Getty Images; plates 4, 7 © PA Images; plate 9 © Reuters; plates 2, 5, 12, 13 © Rex Shutterstock/AP; plate 15 © EPA/EFE The Walt Disney Company.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For CitaWho has made this book and much else possible

‘I’m a strange mixture of my mother’s curiosity; my father, who grew up the son of the manse in a Presbyterian family, who had a tremendous sense of duty and responsibility; and my mother’s father, who was always in trouble with gambling debts’

Rupert Murdoch, 20081

‘I would hope they [my children] would lead useful, happy and concerned lives with a very responsible view of what they should and are able to do according to their circumstances’

Elisabeth Murdoch, circa 19892

‘I am a curious person who is interested in the great issues of the day and I am not good at holding my tongue’

Rupert Murdoch, 20123

CONTENTS

Timeline

Preface

Introduction:Rupert Murdoch: The Man, His Method and Me

1 The Corporate Culture

2 Power, Politics and the Murdoch Method

3 Deals

4 Economic Regulation

5 Crisis Management

6 Responsibility

7 Protecting His Assets

8 The Succession and the Pivot

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Select Bibliography

Notes

Index

KEITH RUPERT MURDOCH

TIMELINE

1931

March

Keith Rupert Murdoch born

1950

October

Goes up to Worcester College, Oxford

1952

October

Father, Keith Arthur Murdoch, passes away. Rupert inherits father’s stake. The will is complicated, so the precise date of possession is difficult to pinpoint

1953

Family approves of Rupert becoming managing director of Adelaide papers, News and Sunday Mail

1956

Marries Patricia Booker

1958

Daughter Prudence (now Prudence MacLeod) born

1964

July

Launches The Australian, a serious, nation-wide broadsheet in Australia, and his first new title

1967

Divorces Patricia BookerMarries Anna Torv (now Anna Murdoch Mann)

1968

January

Acquires News of the World

August

Elisabeth Murdoch born

1969

September

Acquires The Sun, at the time a broadsheet

1970

November The first genuine Page Three girl appears in The Sun

1971

September

Lachlan Keith Murdoch born

1972

December

James Rupert Jacob Murdoch born

1973

December

Acquires San Antonio Express, the News, and their combined Sunday paper. First US acquisition

1976

November

Acquires New York Post

1978

August

New York newspaper strike

October

Author meets Murdoch for first time at birthday party for his wife Cita at Lutèce restaurant in New York

1981

February

Acquires The Times and The Sunday Times

1983

November

Acquires Chicago Sun-Times

1985

March

Rupert acquires 50 per cent of 20th Century Fox and the balance in September of that year

September

Rupert becomes an American citizen

1986

January

The Times and Sunday Times move to Wapping and strike begins

1989

January

Acquires William Collins Publishers and combines it with Harper & Row, acquired a year earlier

February

Sky Television launched

1990

January

Purchases two Hungarian newspapers, Mai Nap and Reform

1992

June

Rupert fires Steve Chao over performance at company conference in Aspen

1993

September

Rupert claims satellites threaten dictatorships and is thrown out of China

December

Rupert (Fox) acquires TV rights to NFL for four years for $1.58 billion

1996

James Murdoch sells Rawkus Records to News Corp. in 1996 and joins the family firm

October

Rupert launches Fox News Channel

1998

May

Murdoch issues apology to Chris Patten for cancelling publication of and disparaging his book

1999

June

Divorces Anna Murdoch. Marries Wendi Deng the same month

2001

November

Daughter, Grace Helen Murdoch, born

2003

July

Daughter, Chloe Murdoch, born

November

The Times switches to tabloid format alongside broadsheet, which is abandoned in November 2004 in favour of tabloid format

2005

July

News Corp. buys Intermix which owns Myspace for $580 million, value grows to $12 billion, sold for $35 million June 2011

Lachlan Murdoch resigns from News Corp. after Rupert undermines his authority

2007

August

Acquires The Wall Street Journal

2008

January

Settles defamation suit with author Judith Regan

2011

February

Elisabeth Murdoch sells her company (Shine) to News Corp.

2012

February

James Murdoch resigns from News International and heads to Fox in Los Angeles

April

Rupert testifies at Leveson Inquiry

December

Dame Elisabeth Murdoch dies

2013

June

News Corp. split into News Corp (without the full point) and 21st Century Fox. Succession established as described in the book

November

Divorces Wendi Deng Murdoch

2014

August

Rupert drops out of bidding for Time Warner to preserve credit rating

2016

March

Marries Jerry Hall

July

Roger Ailes resigns as CEO of Fox News and Rupert becomes acting CEO

2017

December

Sells 21st Century Fox Entertainment assets to Disney

2018

January

Murdoch purchases 10 television stations, some in important sports markets.

Note: Dates cover and surround most events mentioned in the book.

PREFACE

When this book was published earlier this year the Murdochs were in the process of selling many but not all their media assets to Disney. In the book I quoted a question Rupert asked, and answered: ‘Are we retreating? Absolutely not. We are pivoting at a pivotal moment.’

Now that the complex asset-disposal process is just about completed, we can see how pivotal the moment was – and the nature of it for Murdoch. As has so often proven to be the case (as analysed in this book), Rupert’s combination of intuition and opportunism is standing him in good stead. So, too, is his cold calculation that the assets he decided not to hold onto would become progressively less valuable within the 21st Century Fox (TCF) structure and, as Disney CEO Bob Iger believed, more valuable as a part of Disney.

Video-on-demand services such as Netflix have made the positions of many of Murdoch’s previous assets (and their like) untenable. Murdoch had planned to spend about $1 billion for TCF programming in 2018; according to The Economist, Netflix will spend $12–13 billion, Amazon close to $5 billion, with rumours putting that figure at $20 billion. In effect, that makes it difficult – indeed, impossible – for Fox (or other traditional media companies, for that matter) to compete for talented writers, directors, producers and on-screen talent. Netflix, for example, lured producer Shonda Rhimes (of Grey’s Anatomy fame) from NBC with an estimated $100 million contract. And Ryan Murphy, another producer with several hits (such as Nip/Tuck) to his name, switched from Fox, his long-time home, to Netflix to accept a five-year deal valued at about $300 million. Dana Walden, co-chief executive of the Fox Television Group, told the New York Times that Netflix ‘sent a message to the entire talent community. The old deals that seemed incredibly lucrative at the time, there’s a new template in town. For any uber-premium creator, the value has gone up 10 times. And Ryan [Murphy] is a once-in-a-lifetime-creator.’

So, pivot Rupert did, ‘play[ing] a bad hand very well’, as Barry Diller (creator of the Fox Broadcasting Company) put it. Better, in fact, than he originally thought he had done. Comcast decided to challenge Disney and, before dropping out of the resulting bidding war, increased the offer for the TCF asset package to $71.3 billion, $18.9 billion higher than Disney’s original bid – and repeated that exercise when it was Sky’s turn to be put on the auction block. That bidding war took Comcast’s winning Sky bid to £17.28 per share; in December of 2016 Murdoch had bid £7.50 for the 39% of Sky he did not already control. This is not the place to recount the various iterations; suffice it to say that the Murdochs will walk away with their share of well over $70 billion when all is said and done – with the possibility of more to come if subsequent, add-on deals eventuate.

Perhaps the more interesting and important aspect of Murdoch’s change of tack is whether or not this is a pivot for Rupert to a good life aboard his yacht with his wife Jerry Hall, and to one of charitable work for his son, Lachlan. (Rupert’s other son, James, has opted for that of a US/UK entrepreneur-investor.) Thus far, the leisurely lives available to father and son are not to be – I characterize such a result as ‘improbable’ in this book.

The sale to Disney did not include the Fox Broadcasting Company network and its 28 local TV stations; the Fox News channel, which is expected to reap about $1 billion in advertising revenues and $1.7 billion in affiliate fees next year; Fox Sports 1 and 2; or Fox Business Network channel, among other assets. Nor did it include News Corp, home of Dow Jones Company and the Wall Street Journal, the USA’s largest newspaper by total circulation; digital real-estate services; the New York Post (Rupert’s money-losing but beloved tabloid newspaper, which he uses to discomfort the comfortable, to paraphrase humourist Finley Peter Dunne, creator in the late nineteenth century of the fictional Mr Dooley); HarperCollins, the second-largest book publisher in the world, with operations in 18 countries; newspapers in the UK (The Times, Sunday Times and Sun); or the television and print properties in Australia that together make the largest media company in the nation. And more. Retaining these properties would satisfy the appetite of most media moguls – especially one about to cash a cheque for multiple billions, at age 87.

Lachlan is now chairman and CEO of what is being called ‘New Fox’. Rupert is executive chairman and Lachlan is co-chairman of News Corp, and old Murdoch hand Robert Thomson is the company’s chief executive.

It pleases the media, important components of which are controlled by Murdoch competitors, to report conflicts between Rupert and Lachlan – and some do undoubtedly exist. But since Lachlan’s return to the family fold after departing over a dispute with some of Rupert’s top aides (most notably Roger Ailes), Lachlan has not looked back in anger; Lachlan is less confrontational than James, and less embarrassed by the pro-Trump tilt of Fox News. He has emphasized to me his desire to see that his father’s legacy is a positive one, and that he includes in that legacy the establishment of Fox News. This is rather like Rupert’s effort to preserve the formidable legacy of his father, Sir Keith. Rupert financed the production of a movie, for example, that presented the governments and military forces involved in the Battle of Gallipoli in the same negative light in which Sir Keith had viewed them – to the annoyance of his critics and the establishment that Rupert has always despised.

Rupert remains in New York, very active in all aspects of the Fox operation – and not just as a caretaker for the assets left over after the Disney sale. Rights to Thursday-night NFL games have been acquired and are proving a good buy, especially when combined with more innovative techniques for capturing consumer attention to ads, and more lively commentary than accompanied these matches in the past. Rupert and Lachlan have made it clear where they intend to take New Fox. The plan is to position the company as a growth company, one that will attract investors who might be put off by the company’s massive position in the newspaper and book publishing industries – deemed unlikely to grow very much or, indeed, likely to shrink as competition from Amazon in the book business and the Internet in the news business eats into earnings.

There will be one difference from the days when Rupert worried very little about excessive borrowing to finance growth when on the acquisition and expansion trails. As this book relates, that attitude brought the old News Corp to the brink of disaster when markets turned, interest rates soared, and over-leveraged companies were threatened with collapse – just when Rupert had borrowed and borrowed again to support the establishment of Sky. That searing experience taught him to ignore the siren call of bankers eager for fees but unconcerned about the long-term fate of their clients.

Lachlan, who reportedly only occasionally attends New Fox meetings (when personnel decisions are being made), remains in Los Angeles, his town of choice before the sale to Disney. He prefers it to New York for several reasons, only one of which is that it reduces the possibility of friction with his father. Los Angeles has a school system that he feels is optimal for his children; it is a bit closer than New York to the Australia where he and Sarah feel so much at home; and it is handy to his newly purchased ranch in Aspen, Colorado, where he can pursue the outdoor activities of which he is so fond. It is also convenient for an executive actively managing News Corp’s Australian assets, which include the country’s only national newspaper, a host of regional papers, the only pay-tv network, and the most-viewed website. In the most recent fiscal year Murdoch’s Australian media holdings generated $9.02 billion in revenues.

It’s not just about money, though. As I relate in this book, Rupert Murdoch is about much more than that. He has a set of social and political beliefs, sometimes changing but best characterized as conservative with a libertarian tilt, and a powerful drive to affect political events. And he has the megaphones with which to trumpet these beliefs and satisfy that drive, whether by supporting politicians who find his agenda congenial, or publicizing issues he deems important. In 2018, he visited Australia – where former PM Kevin Rudd, who had lost the support of the Murdoch media, described him as ‘a cancer on democracy’ – to make his wishes on issues and candidates known to his editors and elected officials. The result was the defenestration of then-PM Malcolm Turnbull. Newspaper circulation may be declining, but by controlling 60% of Australia’s total output, News Corp can affect the agenda of the other media with which Murdoch’s newspapers compete. Whether he is as powerful as Australian politicians seem to believe is uncertain, but they certainly act as if he is – a situation not unlike that prevailing in Britain.

In America Rupert is at the height of his political powers. Fox News is as important to Donald Trump as any media source can be to an incumbent politician. The channel is organized rather like a newspaper, with an attempt to separate news from comment. There is pro-Trump material early in the morning, from which the President routinely constructs his daily agenda, and to which he often reacts while the show is on air. That is followed by news broadcasts, hosted by presenters generally regarded as non-partisan, or in some cases as having an anti-Trump tilt. Then, when dinner is being served or the washing up begins on the East Coast, comes the pro-Trump commentary of which the President is so fond. The commentators and their guests attack Trump critics, defend some of the President’s positions and gaffes, and generally provide grist for the mill of Trump’s core supporters, while anti-Trump channels sputter in ineffectual rage at Fox News’s larger viewer numbers.

Rupert speaks with the President at least weekly, was invited along with Jerry Hall to Trump’s first White House state dinner for France’s president Emmanuel Macron (this was before relations between the two presidents had deteriorated), and received a congratulatory call on the Disney deal from the man who considers himself a negotiator and deal-maker without equal, Donald Trump. This happened before government regulators had cleared it, and no doubt to make certain that Fox News would remain in pro-Trump Murdoch’s hands rather than coming under the control of someone in the anti-Trump Hollywood camp.

In short, although Murdoch may have ended up converting more of his media assets into cash than he had originally planned, he has kept enough of them to sit astride a very extensive empire in the US, UK, Australia and several other countries in which his newspapers are read and televised sporting events watched. He has good working relations with the son who chose to succeed him – and can take satisfaction from the success of his other offspring in finding well-funded happiness elsewhere. He has returned to an expansion mode – and achieved greater political influence than he has ever had before. Doubt that and listen to the complaints of former Australian prime ministers, the anti-Murdoch politicians and press in Britain and the Fox News-haters in America.

Rupert Murdoch’s handing off of his remaining media empire to his heirs might not be the best of all possible worlds he imagined – but the current situation is undoubtedly a very close second best, and a platform for whatever next act opportunity might provide.

Irwin Stelzer, October 30, 2018

INTRODUCTION

RUPERT MURDOCH: THE MAN, HIS METHOD AND ME

‘I count myself among the world’s optimists. I believe that the opportunities we face are boundless, and the problems soluble’ – Rupert Murdoch, 19991

‘His greatest asset is that he is contemporary. He’s always got a new angle on something. He doesn’t just bang on about some old thing’ – John Howard, 20112

‘Murdoch has never made a dollar from his acquisitions of the tabloid New York Post or the well-regarded Times of London. He loves newspapers for the visceral connection to them he feels as the son of a newspaper executive … A chief executive with a stronger affinity for the bottom line would have jettisoned those newspapers long ago’ – David Folkenflik, NPR media correspondent, 20133

I have known Rupert Murdoch for more decades than either of us cares to count. These years were hectic, exciting times that Rupert kindly characterised in a handwritten note as being ‘filled with 35 years of great memories’. I mention that not as a form of name-dropping, but as a warning to readers that I am not certain I have achieved sufficient distance from those years to be as dispassionate in my appraisal of Rupert’s managerial techniques as perhaps I should be. But I have given it a good try.

I am unlikely to forget either the date or the doings at my first meeting with Rupert Murdoch – a small dinner given in honour of the birthday of one Cita Simian in October 1978, at that time an employee of my consulting firm. I told Cita, who later became my wife, that I wanted to give a dinner party in honour of her forthcoming birthday. She responded that two old friends, Anna and Rupert Murdoch, had already organised one. I had not heard much about Mr Murdoch other than that he had bought the New York Post, prompting Time magazine to produce a cover with Murdoch’s superimposed head on a gorilla’s body, the grotesque figure astride New York and a headline ‘EXTRA!!! AUSSIE PRESS LORD TERRIFIES GOTHAM.’ With Cita’s permission I called Murdoch to ask if I might act as a joint host at the dinner. He agreed.

So it was that the Murdochs, Cita with her date, and I with mine, showed up at a fashionable New York eatery for one of the more unpleasant evenings any of us had ever experienced.

Our respective dates probably sensed early on that Cita’s interests and mine were less with them and more with each other, and undoubtedly wanted the evening to come to a quick end. Rupert was in the midst of a battle not only with the print unions, but with the Daily News and The New York Times, competitors of his struggling New York Post. He had purchased the city’s only surviving afternoon daily for $30 million two years earlier, and converted it from the voice of the New York left to a feisty tabloid that took a somewhat different view of events from that of its previous, ultra-liberal owner. And was bleeding red ink. Overmanning was rife in the industry; nepotism ruled on the shop floor and in the distribution network. The publishers, deciding they had had enough, posted new work rules that cut down on staff. Strikes by several unions followed, closing all the city’s newspapers.4 The proprietors were calling for solidarity in the hope of breaking the strike – and in the case of the then-financially-robust New York Times, of prolonging the strike to further weaken and perhaps destroy the New York Post, which it regarded less as a competitor than as an embarrassment to the industry because of its gossipy nature and its place on the right of the political spectrum. It is an old adage that The New York Times is read by people who think they should run the country, and the New York Post is read by people who don’t care who is running the country so long as they do something truly scandalous, preferably while intoxicated. Unfortunately for the pretentions of The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, now owned by Murdoch, is read by the people who actually do run the country.

Since solidarity with competitors is not Rupert’s long suit, he broke with his fellow publishers and settled with the unions after bearing the losses of the strike for about six weeks. The Post, sniffed W. H. James, publisher of the Daily News, ‘was seeking the temporary quick buck at the expense of its former allies’.5 Indeed. Murdoch knew he could have the market to himself for at least long enough to acquaint potential readers with the Post, and to earn some advertising revenue from retailers starved of outlets in which to trumpet their wares – this was before multiple alternatives to print advertising became available. Rupert took personal charge of the Post’s labour negotiations – an early hint of how he reacts in a crisis – and settled with the unions, becoming for about a month the sole newspaper available on the streets of New York City. Murdoch agreed to a ‘me too’ deal: he would give the unions whatever they were able to wring from the Daily News and The New York Times.

That go-it-alone move took place only a few weeks before the dinner to celebrate Cita’s birthday, with rather unfortunate consequences for the success of the party. Because he had a stake in the terms to which the other papers would finally agree, and because negotiations between the unions and the other publishers were reaching their climax, Rupert was repeatedly called from our table to take telephone calls from his staff, the union representatives and, I assume, Mayor Ed Koch, who owed his election to the New York Post and who was worried about the eighty-three-day strike’s adverse effect on retail sales and employment in the city. Meanwhile, Anna presided graciously over the remains of the party, while the rest of us hoped dessert would be served quickly so that we might get the evening over with.

After that dinner party I was increasingly included in the overlapping social lives of the Murdochs and Cita. When Rupert and Anna first came to America they had a weekend place in upstate New York, where Cita, then a senior aide to Governor Hugh Carey, was living. They had been told by mutual friends to look up Cita, which they did. Rupert said she had been described as ‘this interesting young woman’, and he undoubtedly realised she might be a useful contact in New York politics, to provide introductions (this being the days before the purchase of the New York Post gave him automatic entrée into those circles) and enrich his understanding of the personalities, feuds and issues that dominate life in New York City and Albany.

Rupert and I quickly became interested in each other’s news and views about the US and world economies, politics and mutual acquaintances, as well as the gossip that contributes to the vibrancy and vitality of life in New York. A friendship blossomed, with many private dinners and shared events. At one point the Murdochs – Rupert, Anna, Liz, Lachlan and James – spent Thanksgiving with us in our postage-stamp-size log cabin in Aspen, Colorado, the boys sleeping in an attic, the others in two tiny bedrooms.

A good time was had by all, if you count as a good time the robust arguments among the Murdoch clan about the meaning of current news events. Such discussions were, and long remained, part of Rupert’s ongoing training programme for his children. When things got out of hand, as they frequently did, Anna would soothe wounded feelings, in this case by refocusing attention on the carving of the Thanksgiving turkey and changing the subject to which nearby house might be suitable for purchase by the Murdochs. At that time, when the children were of an age at which they had a strong preference for vacationing with friends, Rupert and Anna wanted something that would enable them to do just that without sacrificing family time. The home they finally settled on, a stone’s throw from our own, had an indoor pool and multiple bedrooms. And enough large public spaces to accommodate the inevitable parties for business associates, politicians and others for whom there was only one conceivable response to a Murdoch invitation.

I recall telling Rupert as I left for the five-mile drive into town one morning that I was going in to buy a newspaper (no iPads in those days), but didn’t want to take him along since he might do just that and end up owning a small-town newspaper. Instead, I took James, aged nine, who educated me in an Australian’s concept of space. Our house sits atop a hill on a small plot, most of which is too steep to be habitable. When we had driven about four miles from the end of our property, in the direction of downtown Aspen, James asked me to let him know when we reached the end of our property, which we had actually left some four miles back.

At one point in our developing relationship Rupert invited me to breakfast at his New York apartment and said that it would be unfair of him to continue picking my brains on economic matters without paying me a fee. Without some such arrangement, he wouldn’t feel free to call, at least not as frequently as he had been doing. Since the Murdochs were Cita’s friends initially, I was reluctant to accept a fee, but Cita advised me that if I did not I could count on far fewer interesting conversations with Rupert. So we agreed a consulting arrangement, terminable by either of us whenever we saw fit.

During the following decades I was a consultant to Rupert and to his company, advising him – although sharing views with him might be a more accurate description – on whatever topic he cared to raise, day or night, weekday or weekend: the trend in interest rates; the development of regulations in the UK and the US and, at times, in Australia; the prospects for the Chinese economy and the potential for investment; his expectations concerning his lifespan and the corporate succession that, deep down, he did not believe would ever be necessary. I had no illusions that I was the only person or even the most important person with whom he discussed whatever happened to pique his curiosity or interest: it was his practice not to share with anyone the information he had picked up from other experts, which meant that each of us was being tested against a huge database, the contents of which we could only guess.

My time as adviser and, I like to think, friend covered:

• the years of rapid expansion and multiple acquisitions;

• the financial crisis resulting from Sky’s expensive challenge to the BBC, beneficiary of some £3.7 billion in guaranteed income from the licence fee,6 which BBC supporters claim ‘is not just another tax. It is a payment for a service’,7 although payment is due even if you never use the ‘service’ by watching BBC channels;

• the struggle to get Fox News onto the key New York City cable system to challenge the dominant liberal broadcast networks and cable news channel CNN;

• his twenty-year stalking of The Wall Street Journal;

• times when the US regulatory authorities were challenging an acquisition or sale of a company, or the UK authorities some of his business practices;

• financial problems threatened his hold on his company and his dynastic ambitions;

• a campaign in The New York Times aimed at upending his effort to purchase The Wall Street Journal;

• the day he had to tell his mother that he would seek American citizenship so that he would be eligible to meet government regulations concerning ownership of television stations.

And more. I do not pretend to have been a key player in these and other events, or to have been the only person Rupert asked to organise his thoughts into important speeches such as his provocative MacTaggart Lecture in 1989 or his consequential 1993 address extolling the key role satellite broadcasting might play in bringing down dictators, of which more later. In the case of the regulatory issues I often had the lead role in preparing presentations for the American and British authorities. In others, I offered such advice as I could, and in still others provided a sounding board as Rupert considered his options. At other times, I contributed merely by being there. In no sense was I ever ‘the chief adviser to Rupert on just about every matter’, as Woodrow Wyatt, a long-time Murdoch friend with significant influence in the Thatcher government and a columnist for the News of the World, claimed,8 or Rupert Murdoch’s ‘secret agent’ or his ‘representative on earth’, as the left-wing press would have people believe,9 or stand ‘in the same kind of relationship to Murdoch as Suslov did to Stalin’, as the right-leaning Spectator would have it.10 Rupert needs no ‘representative on earth’; his intelligence, political and financial shrewdness, and the power of his media empire are enough to provide him with any access he might need to the business and political communities. As he put it to the Leveson Inquiry, appointed in response to the hacking scandal, when asked whether I was his ‘economic guru’: ‘No, a friend, someone I enjoy talking to.’ I will settle for that. The addition of ‘He’s a fine economist’ was frosting on the cake.11

We were both fortunate that I was financially independent, which allowed me to be incautious in situations in which company employees might reasonably feel more constrained. In the many years in which I ran my consulting firm, my partners and I held to the view that no client should be allowed to become a large enough portion of our business to make us fearful of losing him. That, I argued, was in the client’s interest as it assured him of advice unencumbered by the financial needs of the firm. So we established an informal rule that no client would be allowed to become so large that it accounted for significantly more than 5 per cent of our total revenue. After my partners and I sold the firm, and I became a freelance, solo consultant, I could not take on and properly serve enough clients to observe a 5 per cent limit. I preserved the spirit of that rule by not allowing any client to be so important that I would fear antagonising him when called on to advise him. In Rupert’s case, the practical application of the ‘independence rule’ was to retain other clients, the right to return to my position at Harvard’s Kennedy School, and have an understanding that the engagement could be terminated by either party. Wyatt, a keen observer who included Cita, myself and Rupert at many wonderful dinner parties, writes in the diary he swore he was not keeping, ‘Irwin still argues with Rupert and is always ready to pack his bags and go if Rupert doesn’t like it. But he remains very fond of him, as I do.’12

All of this resulted in an unanticipated ‘bonus’: the complete freedom, with no confidentiality agreement, to write this book. As I reflect on the decades of consulting with Rupert, I have come to feel that the pace of events, the often urgent nature of the decisions to be made, prevented me from realising that what at the time had seemed to me successive applications of often-brilliant ad hoc solutions were in fact applications of a management method, one that might be of interest to the following: corporate leaders faced with the need to develop a trade-off between central control and the encouragement of entrepreneurship – intrapreneurship, to use the more fashionable term – and creativity, but suffer from overexposure to traditional management courses and texts; entrepreneurs and executives who must do computations before putting what Rupert often calls ‘the odd billion’ at risk, and who must balance the various interests of owners and stakeholders in these post-2008 financial crash years in which corporate behaviour is under a microscope; policymakers who must protect consumers without at the same time stifling innovation by protecting incumbents; and, of course, to Murdoch-watchers from New York to London to Beijing to Adelaide who have always followed Rupert’s career with a mixture of curiosity, wonder, admiration and distaste.

What I have come to think of as the Murdoch Method, at times the stuff of the tabloids, at others of the financial press, has enabled Rupert to build his empire to a globe-girdling enterprise with 100,000 employees, a market cap (total value of all shares) of some $56 billion,13 and annual revenues of more than $36 billion in its 2017 fiscal year.14 But that very same style and approach to business has at times almost brought him down. The management techniques that allowed him to invade the turf of formidable competitors such as the BBC and the American television networks also led him to fail to build Myspace and other acquisitions into the powers they had every possibility of becoming, and to risk ruin, or at the least embarrassment, by excessive reliance on short-term borrowing and by creating a culture that did not always respect the limits beyond which even tabloid journalists cannot stray with impunity. ‘We have made some bad mistakes along the way,’ Rupert told a group of his executives before he had scandals to add to his list. ‘We have had our share of one-issue magazines, odd blunders by some of our editors and managers, and financial overreaching by me. But we’re still here.’15

The Murdoch Method is the sum total of the management techniques that grew out of his attitudes and conceptions, many of them conscious, many not. Rupert did not sit down and make a how-to-manage list, which makes the idea of a Murdoch Method mine, not his. Nor did he come to management without a set of guiding stars – most important, his parents. To them we should add a list of fundamental beliefs: in competition as a system of providing choice and rewarding the able; in a mission to discomfit an exclusionary establishment; in keeping his word; in the need for him to be directly engaged at all levels of his companies; in taking risks others would not take, relying on his own estimate of the risk–reward ratios; and, above all else, in a plan to pass control of his empire to his children. Rupert lives on what he described to biographer William Shawcross as ‘the risk frontier’, and relies much more on his own informed intuition than on formal risk-management techniques – intuitive, but an intuition informed by an ability to separate the relevant from the irrelevant in the information he gathers from a global network of contacts tapped as he searches for the latest news and gossip from business, political and other informants. He knows as well as anyone else that risk-takers don’t always win, but is convinced that safety first does not build great companies, and that failure can provide valuable lessons to future behaviour. Those of us who have watched him blow out a knee skiing, or lose part of a finger crewing with far younger men in a dangerous yacht race, or been with him when he drives from office to home when late for a dinner party, will attest to the fact that he finds it exhilarating to take chances, even if some have less-than-happy endings.

The Method also includes a willingness to take a long view denied executives who must, or believe they must, respond more immediately to the desires of shareholders for short-term gains. I remember helping prepare notes for a speech for Rupert in which I referred to a company operation becoming profitable after seven years, and Rupert inserting the word ‘only’ before ‘seven years’. There is an ongoing battle between executives who feel pressured to wax triumphant on quarterly calls with Wall Street analysts, and critics of what they see as capitalism’s excessive emphasis on so-called short-termism. Never mind that these very critics often also object to a corporate structure based on two classes of stock, voting and non-voting, an arrangement that gives Rupert and other executives who do not own a majority of their company’s shares freedom from the need to elevate short-term earnings results to a primary goal.

Another ingredient of the Murdoch Method that might be worth studying for those who want to build or manage great companies is its view of traditional notions of proper corporate organisation, such as establishing what to most executives are essential: clear lines of authority. Rupert worries that overly rigid rules will impinge on creativity and the sheer joy of coming to work in the morning that can be such a key motivator of the best and brightest. A distinguishing characteristic of the original News Corp. and its successor companies, 21st Century Fox and News Corp (without the period), is a professed disdain for the sort of organisational structure on which other companies lavish so much time. Rupert puts it this way:

Fortunately for our company all of us know that the structure can work well only when it is periodically subverted. This means that when someone jumps ‘the chain of command’, he or she is not disciplined for doing so, but instead rewarded for that initiative if the subversion of the system helps us to reach our goals … We are greedy: we want to develop a management technique that gives us the best of entrepreneurial individualism AND the best of organisational teamwork.

As one executive put it, ‘While our competitors are organizing and communicating, we are taking away their markets.’16 I have often thought that anyone attempting to prepare an organisation chart of the old News Corp. or the new News Corp or 21st Century Fox would first have to study the art of Jackson Pollock.

But make no mistake: when attention to organisation is important – among other things to minimise tax burdens, as many multinationals do in performance of their fiduciary obligation to shareholders; to provide upward paths for talented employees; to make certain that informality does not morph into chaos; and to maximise interaction and creativity – attention is paid. Murdoch believes that ‘structure alone can’t take us very far’, but knows that the day is past when fleeting conversations in hallways, or one-day drop-ins by him, will provide necessary coordination and interaction. So he introduced what he calls a ‘more formal consultative structure’, but done in a way that reflects his ambivalence about that action: ‘Such a structure will be more formal than we have had in the past, but much more relaxed than is characteristic of the corpocracies with which we have to contend in the marketplace.’17

There is much to learn, too, from how Murdoch balances his desire for growth, profit and the construction of a dynastic empire against what he sees as his requirement to fulfil his father’s interdiction ‘to be useful in the world’.18 There is a good deal of discussion these days, some of it useful, about corporate responsibility, and debates about whether corporate managers can best serve their constituents, and by extension society, by concentrating on maximising profits or by including in their remit responsibility to what are called ‘stakeholders’ – employees, consumers and the environment. This is an especially important question for media companies in general, and more particularly for News Corp and now 21st Century Fox, headed as they are by a man who is his parents’ son and who has strong views on matters of social and political policy. Media companies are different: they are not ordinary manufacturing operations, or trophy properties like sports teams. They can shape opinion and tastes; they can degrade the culture or enrich it; they can help to solidify the status quo and the place of the dominant establishment, or remain outside the establishment and make their voices heard on behalf of members of society scorned by establishment elites. But media companies – electronic or print – can only be effective in the long run if they are profitable, as James Murdoch pointed out in his 2009 MacTaggart Lecture, to the consternation of his sister, who three years later used her own MacTaggart Lecture to challenge what she saw as his excessively narrow view of the role of media companies.

The special characteristics of media companies cannot change the fact that, like all private-sector enterprises, they can be profitable and operate in a socially beneficial manner only if they are well managed, especially at a time when good management must include developing responses to what in today’s jargon are called ‘the disrupters’, or, as Joseph Schumpeter better put it, to ‘a perennial wave of creative destruction’.19 The so-called disrupters are challenging not only the market share of traditional media companies, but their very existence, by developing new sources of what is called ‘content’, new ways of delivering such news and entertainment to the multiple devices consumers now possess, and by offering advertisers precisely targeted audiences at reasonable prices.

My hope is that elucidation of the Murdoch Method, its successes and failures, its virtues and its limitations, will prove valuable to all those with corporate management responsibilities, and to those wishing to learn more about the public policy issues surrounding the media business.

My close association with Rupert ended when he appointed his son James to oversee the company’s UK and other overseas interests. James (full disclosure here: Cita is his godmother) had his own cadre of loyalists and advisers, and quite sensibly preferred to have them around him as he moved up the News* ladder. The last thing he needed was to have his father’s old friend and consultant hanging around, perhaps reporting back to Dad should he stumble while transferring his talents from Sky to print and other areas of the Murdoch operation.

Looking back, I am not surprised that I found working with Rupert so exciting. For one thing, the immediacy of the media business is intrinsically intoxicating – get it quickly, get it right, move on. For another, as this book will make clear, the Murdoch Method differs from the calmer, less personal, more routine methods of many of my other clients: being around Murdoch and News is not the same thing as strolling the corridors of your local electricity company. Finally, and most important, the anti-establishment DNA that underlies the Murdoch Method had and has great appeal to this Jewish consultant, who initially found the doors to most ‘white shoe’ law firms (many now defunct), utilities and other businesses off-limits. My ethnically impaired consultancy eventually succeeded because of the hard work and intelligence of my partners and our staff, many of whom could not even obtain an interview from companies dominated by the WASP ascendency. One perfectly polite and sensible client, who hired my firm because we were able to communicate with regulators who respected facts rather than lineage, told me over dinner he was glad that the new Civil Rights Act did not make Jews a group that could benefit from its anti-discrimination provisions, because, unlike the groups that were protected, we would be upward-thrusting and after his job. Another congratulated me on starting the firm, and told me that if he ever hired Jews, we would be among the first. No surprise that I understood and was driven by the same motive as Rupert, to take on and win in a game rigged against us, although for different reasons.

A word about how this book has been written. I have never kept a diary, for two reasons. First, I was so busy doing that I had no hours to spare in which to record what I had done. Second, whenever I considered keeping such a record, I always rejected the idea lest the keeping of the diary end up dictating what I did, rather than the other way around. So this book may contain errors of detail. I decided that it would be better to live with such unfortunate mistakes than to ask Rupert and his staff to check some of my recollections against their records, for that would have meant notifying them of this book before its publication, which I did not want to do. So, advance apologies for slip-ups and mis-recollections of the incidents in which I was heavily or peripherally involved. I believe it fair to say that those recollections, when possible checked against public reports, provide a sufficient and solid basis for any conclusions I have drawn.

* Throughout the book ‘News’ is used as a shorthand for the Murdoch companies.

CHAPTER 1

THE CORPORATE CULTURE

‘The psychological key to Murdoch is his capacity to continue to think of himself as an anti-establishment rebel despite his vast wealth and his capacity to make and unmake governments’ – Robert Manne, in David McKnight’s Rupert Murdoch: An Investigation of Political Power, 20121

‘I am suspicious of elites [and] the British Establishment, with its dislike of money-making and its notion that public service is the preserve of paternalists’ – Rupert Murdoch, 19892

‘Throughout his [Murdoch’s] long career, he has fixed his gaze on an established competitor and picked away at its dominance … His … is … a broader grudge match against the toffs, the chattering classes, and the top drawer of society on whatever continent he happens to find himself’ – Sarah Ellison, Vanity Fair, 20103

Never mind the composition of the Murdoch companies’ boards; never mind the organisation chart, if there is one; never mind any of the management tools that have been layered on the one thing that underpins the management of News Corp4 – its culture. All companies have cultures – a definable ethos, a style of thought, informal means of communication, systems of rewards and punishments. It doesn’t take a keen-eyed consultant to notice the difference in the cultures of, say, your local utilities and Google, or Facebook and General Motors. Or to notice that many of the companies in a particular industry have similar cultures; witness the distinctive dress styles and political outlook of many Silicon Valley executives, and the very different uniforms, even now, of most investment bankers and many lawyers.

Nowhere is a guiding culture as important a determinant of how a company is run as it is at News Corp. The managerial method that reflects that culture – the Murdoch Method as I have chosen to call it – has propelled the company from a single newspaper in an obscure corner of Australia into a multi-billion dollar media empire. That style, which has produced the good, the bad and sometimes the ugly, can best be described as arising from a rather unique view of the world: it is ‘them vs us’, we outsiders versus, well, just about everyone else, including ‘the elite’, any powerful incumbent that Murdoch selects as a competitive target, and most especially ‘the establishment’.

No matter that Rupert benefited from what even he must admit is an elite education at one of the finest prep schools in the world, Geelong Grammar, the ‘Eton of Australia’, which in later years he claimed he did not enjoy, ‘although I’m sure I had some happy times there – I was there for long enough’,5 and Oxford, which, judging from his later benefactions to Worcester College, he seems to have enjoyed.6 No matter how successful he has been, no matter the lifestyle that such success permits, Rupert continues to identify himself as an outsider – outside conventional cultural norms, outside the models on which other media companies are built, outside the Australian, British and (later) American establishments.

Definitions of the ‘establishments’ vary, some using the rather vague ‘its members know who they are’. Owen Jones is more specific: ‘Powerful groups that need to protect their position … [and] “manage” democracy to make sure that it does not threaten their own interest.’7 Perhaps the most useful for our purposes is Matthew d’Ancona’s definition of a member of this ‘caste’ as ‘the privileged Englishman: such an individual grew up surrounded by Tories, took for granted the fact that he would have homes in the country and in London … and inhabited a social milieu in which everybody knew everybody.’8 Rupert, owner of The Times, which media commentator Stephen Glover is not alone in calling ‘the newspaper of The Establishment’, believes the establishment inhibits social mobility, and will fight fiercely to retain its privileges. Sitting atop the establishment pyramid is the Royal Family, many of the members of which Murdoch often characterises as ‘useless’, and supporting the structure from the bottom are the deferential cap-doffers. Here is the way Rupert, invited to address the 750th anniversary celebration of the founding of University College, Oxford, hardly a rally of radicals seeking to ‘occupy’ the Sheldonian Theatre, chose to describe the virtues of the technological revolution in the world of communications:

You don’t have to show your bank statement or distinguished pedigree to deal yourself into a chat group on the Internet. And you don’t have to be wealthy to e-mail someone on the far side of the globe. And thanks to modern technology … you won’t have to be a member of an elite to obtain higher education and all the benefits – pecuniary and non-pecuniary – that it confers.

In this regard, Rupert is rather like all my Jewish friends who rose in the professional and business worlds in New York City despite (I rather think because of) an effort by ‘the establishment’ to keep us in our place. No amount of success can change our view of ourselves as outsiders even though many of the previously restricted clubs and apartment buildings are now officially, and in some cases actually, no longer off-limits. In Rupert’s case, it was first the Australian establishment that found him unacceptable because his father’s attacks on the Gallipoli campaign had been unwelcome reading for the powers that be in the government and the armed forces. Then, the British establishment would not accept an Australian interloper, especially one who published the irreverent Sun. Add to the establishment charge sheet against Rupert the rumours that he is a republican at heart, stifling his anti-monarchy views in deference to his mother and her memory, and aiming his media products specifically at those outside of the establishment, at men and (according to Rupert) women who deemed it harmless fun to ogle semi-clad girls in The Sun until that feature was dropped, who prefer sport to opera on TV, families that prefer to watch a popular movie to listening to some elevating lecture, and people who enjoyed the first-rate political commentary featured in The Sun. I was occasionally called upon to contribute the typical 600-word commentary, and the standards of exposition required of such political commentary and reporting on America were exacting indeed.

No matter that Page Three girls are gone, and that they were not introduced into the paper by Rupert. That feature, which passed its sell-by date a few years ago, was the invention of Larry Lamb, the first editor of The Sun. Rupert was in Australia when the first such photo appeared, and professed himself ‘just as shocked as anybody else’, although he later called what became a national institution ‘a statement of youthfulness and freshness’.9 Rupert’s mother undoubtedly disagreed, as she did with other features of the tabloid. In a widely watched television interview, she complained of his gossip columnists’ invasion of the privacy of the royals, celebrities and others who made it onto the pages of the Murdoch tabloids. To critics confronting him with his mother’s comments, a chuckle and ‘She’s not our sort of reader’.

No matter that Murdoch’s Sky Television offers significantly more ‘high culture’ programming such as operas than the establishment’s beloved BBC ever did: to the elites you are either ‘in’ or ‘out’, and Rupert, by his choice and theirs, most definitely is ‘out’, even though by ordinary metrics – wealth, power, influence – he most definitely is ‘in’.

In America, the old establishment quite rightly sees in Murdoch’s Fox News Channel a threat to its ability to control the political agenda and consensus, and in his New York Post an assault on its notions of propriety. Homes in Sydney, London, New York and Los Angeles, among other places, flitted to and from by private jet, possession of a beautiful yacht and other trappings of great wealth cannot change Rupert’s vision of himself as an outsider opposed to and at times reviled by a ‘them’ that he believes to be impeding economic growth with their sloth and aversion to innovation, and upward mobility by their snobbery and dislike of ‘new money’. For a child of a child of the manse, imbued with a demanding work ethic, it is perfectly consistent with material success to retain the outlook of an outsider, especially for an Australian-born mogul, raised in ‘an unofficial culture imbued with … hostility towards the country’s class society and snobbery. Above all, Australian culture … celebrated the ordinary citizen, opposing the elite.’10

That the culture of the Murdoch enterprise has deep Australian roots there can be little doubt. Rupert puts it this way: ‘Our Australian company … will always be the cultural heart of what we are – adventurous, entrepreneurial, hard-working and with a special loyalty and collegiality in all that we do.’11 His eldest son, Lachlan, echoed that sentiment years later: ‘An Australian influence nourishes the family, even in the States ... I have got to say that I love both countries deeply, and they are both an essential part of my identity.’12 To which his father added, ‘I share my son’s sentiment.’13

The Murdochs’ pride in their Australian heritage exists despite Sir Keith Murdoch’s constant battle with the establishment there over his decision to publicise the senseless slaughter of Australian soldiers at Gallipoli. Then a young reporter, Keith defied military censorship while reporting on the First World War Gallipoli campaign, the Allies’ failed attempt to knock Turkey out of the war by seizing control of the Dardanelles and capturing Constantinople (modern Istanbul). Keith Murdoch drafted what is now the famous Gallipoli Letter, laying out in vivid prose and great detail the mismanagement of the campaign by British officers selected on the basis of their social standing, the poor morale of the troops and the unnecessary waste of young lives.14 He delivered it to the Australian prime minister and to Britain’s minister of munitions, David Lloyd George, who passed it on to Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, all in violation of Keith’s signed agreement ‘not to attempt to correspond by any other route or by any other means than that officially sanctioned … [by] the Chief Field Censor’. The result was the sacking of General Sir Ian Hamilton as commander of the Allied Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, the removal of Winston Churchill from the Admiralty and, soon after, the withdrawal from the Dardanelles of Australian and other Allied troops, but not before suffering 142,000 casualties, 28,000 of them Australian. Of the 44,000 killed, 8,700 were Australian,15 this in a country of under five million at the time. The United Kingdom, with almost ten times the population of Australia, took fewer than three times as many casualties. That Aussie casualty rate, the result of poor leadership, proved to Rupert that his father had done the right thing, and that the criticism of him was unjust. Some sixty-six years after his father’s letter was published, Rupert funded Gallipoli, a movie set on the Anzac battlefield, graphically illustrating the futility of the campaign. It won the award for ‘best film’ and numerous other ‘bests’ from the Australian Film Institute. Murdoch family ties run deep and long.

Rupert styles himself not only an outsider, but also a revolutionary. In his student days, he kept a bust of Lenin in his rooms at Oxford, rooms that were ‘one of the best rooms in college – the De Quincey room’.16 He dismisses such behaviour with ‘I was young and even had other hare-brained ideas’.17 My guess is that the episode was not due to the mere youthful innocence of a university student, but was aimed at upsetting the British establishment.