18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

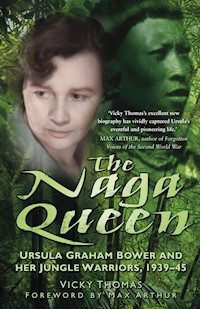

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1937, Ursula Bower visited Nagaland at the invitation of a friend, and on a dispensary tour encountered the Naga people. She was so taken was with their striking dignity, tribal pride and unique culture that she arranged to live among them to write an anthropological study. But she became more than an observer – living alone among them, Ursula was integrated into their village life, becoming their figurehead when in 1944 the Japanese invaded the jungles of Nagaland from Burma. The Nagas turned to her for leadership and with the support of General Slim, her Naga guides were armed and trained to patrol and repel the Japanese incursions. The Nagas' courage and loyalty were duly recognised, and after the conflict Ursula, with Naga support, went on to run a jungle training school for the RAF. Later, with her husband, Tim Betts as Political Officer, she worked among the volatile tribes of the remote Apa Tani Valley, bordering Tibet. Following the Independence of India in 1947, Ursula returned to her highland roots, but to her death in 1988, her experiences among the Naga people shaped and directed her life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

To Peter, who would have been so proud

Acknowledgements

So many people have helped to bring the story of Ursula Graham Bower to light that it’s hard to know where to start, but I will begin with Max Arthur, for whom I was carrying out research at the Imperial War Museum when I stumbled on a transcript of an interview with an extraordinary Englishwoman, living alone among tribesmen in the hills of Nagaland. I would probably never have embarked on my own research had it not been for Max’s encouragement and enthusiasm for my own project.

After Googling ‘Naga Queen’ I found a page on the Burma Star website which featured a short synopsis of an as-yet-unwritten biography by Catriona Child (now Kakroo) – Ursula’s daughter. To my relief this book had not been started, but after meeting with Catriona we agreed that I should write Ursula’s story and she gave me three heavy crates of family documents – letters, diaries and photos. Without the insight and detail from this family archive, TheNaga Queen would never have been possible – and I thank Catriona for trusting me with such valuable family artefacts and for giving me so much personal information and a string of connections to relatives and friends who added a different perspective to my picture of Ursula.

Among these people who so kindly welcomed me to their homes and regaled me with memories and anecdotes were Ebenezer and Isabel Butler. Despite having recently been flooded out of their Carlisle home, they entertained me royally and shared stories of Eb’s time at Ursula’s jungle school – she made an impact on him undiminished by the years. Geraldine Hobson was just a child when her father Philip Mills was Governor’s Secretary and Director of Ethnography in Assam during Ursula’s first visit to Nagaland, having formerly been Subdivisional Officer. He not only encouraged Ursula in her anthropological research but he and his wife became firm family friends – my thanks to Geraldine for an enlightening day sharing her memories and her father’s ‘Pangsha Letters’.

Then Catriona put me in touch with Ursula’s cousin Joan Shenton, who recalled childhood anecdotes and shared family photos. I was privileged to meet Yongkong, then resident in London, who had been part of the Naga delegation to the UK in 1962, and who stayed with Ursula and Tim at their farm on Mull. A very elderly gentleman, sadly now passed away, he embodied the Naga people’s deep and long-lasting gratitude and affection for Ursula – another valuable insight into Ursula’s relationship with her Naga family.

My thanks go too to Professor Alan Macfarlane, now Emeritus Professor of Anthropological Science and Life Fellow of King’s College Cambridge, who generously gave me carte blanche to use material from his 1985 video interview with Ursula – since it was never possible to meet Ursula in person it was wonderful to hear her recollections in her own voice.

Finally, I want to thank Ryan Gearing of Tommies Guides Military Booksellers and publishers, who brought Naga Queen to the notice of Jo de Vries at The History Press, who recognised a remarkable story when she saw one!

To all these people, my profound thanks – it wouldn’t have been possible without such generous support and help.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

1The Early Years

2Roedean

3The Reluctant Debutante

4From Kensington to India

5Nagaland

6The Fascination of the Hills

7Ursula – the Anthropologist

8Going it Alone

9Black Magic

10The World at War

11Mixed Receptions

12In Exile

13Tribal Law

14The World Beyond the Hills

15Christmas and the Spirit World

16News from Home

17Cats – Big and Small

18Masang

19War Comes to the Far East

20The Burma Refugees

21‘V’ Force

22Watch and Ward

23The Japanese Arrive

24Meeting Slim

35Searching for the Japanese

36The White Queen of the Nagas

37The Proposal

38Two Weddings

39Tibet

40Indian Independence

41Leaving Tibet

42Back in England

43From Nagaland to Scotland

44The Nagas in Trouble

45The Last Years

46Pilgrimage to Nagaland

Plates

Copyright

Foreword

Vicky Thomas often shared details of her latest research with me, but in 2003 one story really captivated her, that of Ursula Betts, a lone Englishwoman, living among Naga tribesmen in the remote jungle-covered hills north of Assam on the North-East India-Burma borders during World War II. She eventually tracked down Ursula’s daughter and with her co-operation, the help of other friends and family, and with Ursula’s dairies and additional research she has now written The Naga Queen. Her outstanding research shines from the pages, giving a special insight into the personality and influences that drove Ursula’s courageous and pioneering spirit.

It would have been exceptional enough for an Englishman – an outsider – to gain the confidence of the naturally cautious former head-hunters in Nagaland, but for a woman to be so accepted was even more extraordinary. The redoubtable Ursula was not only accepted, but became the leader of these tribesmen in their actions as guerrilla scouts when the advancing Japanese threatened their homeland. The story of Ursula’s life among the Nagas unfolds with humour and pathos for hers was a highly unusual relationship with the tribesmen – a blend of employer, mother and friend. But after the Japanese threat was neutralised, Ursula’s story becomes an even more romantic one. Still hungry for adventure, Ursula and her husband Tim move into the wild and remote Subansiri territory towards the Himalayas for him to administer as a Political Officer. The area had only recently been charted in 1945 and was home to a number of turbulent warring tribes, which tested the diplomatic and tactical skills of Ursula and Tim to their limits. A new episode opens – again full of personal insight and first-hand detail – a ground-breaking and pioneering tale which not only follows Ursula’s life but portrays the historical situation in pre-independence India.

Ursula Betts overcame many obstacles and setbacks to pursue her dream of adventure. I am so glad that Vicky Thomas’s excellent new biography has vividly captured Ursula’s eventful and pioneering life.

Max Arthur

London, November 2011

Introduction

In the humid October heat of Assam, in the hill town of Dimapur, a Scottish girl in her mid-twenties stood by her car, fanning herself and swatting away the flies. She was waiting for the only train of the day to arrive at the small railhead on the Nagaland border. At last a growing rumble and flurry of local activity heralded the arrival of the train from Bundu, on the Assam plain below. Alexa Macdonald hurried across to where a motley assortment of local Indian traders and British ex-pats were unloading and boarding. As the melee cleared, Alexa picked out a tall girl, standing alone surrounded by smart British luggage, and ran across the dusty track which served as a platform to greet her friend, Ursula Graham Bower.

Travelling alone from London by sea, Ursula’s journey had been a long and daunting one since setting out on 25 September 1937. After a long sea crossing, she finally arrived in India at the end of October, and then negotiated her way from Calcutta by train, then steamer into Assam. After crossing the Brahmaputra at Bundu and boarding a final train, Ursula had weathered the last bone-shakingly uncomfortable leg of her journey, cheered by the prospect of joining Alexa and finally being able to relax in familiar company. Alexa’s brother, Ranald, was working in the British administration of the Indian Civil Service in Imphal, and when he had asked Alexa to come out and housekeep for him during the winter, her thoughts had turned immediately to her friend Ursula. A trip to India would be just the sort of adventure she would love, and Alexa wrote to Ursula at once, inviting her to come out and keep her company for a few months.

The girls loaded the luggage into the car, Ursula climbed gratefully into the passenger seat and Alexa drove off into the thick surrounding jungle towards Imphal. The scenery and vegetation were like nothing Ursula had ever seen before. Dense forest, draped with tangled creepers blocked the light above the rough road, then, as the route began to climb, they came to more open territory. Cliffs and streams turned eventually to low-ground forest then a wide mountain landscape. The car bumped and bounced over the uneven zigzag road and progress was slow. They had covered some forty tortuous miles when they rounded a bend and there, walking towards them, were four men.

To Ursula’s surprise, these were not the slender Assamese of the low country – there was a more Filipino or Indonesian look to them – but on consideration, their closest resemblance was to Mongolians. They were stocky, with the muscles of their copper-coloured shoulders and torsos sharply defined above their native kilts. They stepped aside to let the car pass and Ursula sat back in her seat, stunned.

‘Lexie, for goodness sake – who are they?’ Alexa looked surprised and said simply, ‘Nagas’. Ursula recalled that moment for the rest of her life. Of course… they were Nagas. ‘I could not think at the time what I knew about Nagas, or where I had seen Nagas – I didn’t know what it was, but it was real déjà vu – which disappeared as soon as it had hit me’, she later recalled.

Imprinted on Ursula’s mind was the splash of colour of their woven cloths, their shining muscles – it was a flash of something timeless and intriguing. ‘Just one look and they were gone, and I was left with my head fairly going round, wondering what on earth had happened to me. I knew Nagas – I was certain I knew Nagas. I just didn’t know where I was.’

In that moment Ursula’s life was changed forever – things would never be the same again.

1

The Early Years

The year was 1910, and in Portsmouth the Fleet was in as the nation enjoyed a period of peace at the end of the Edwardian age. A large number of naval officers were on shore leave, among them the dashing Commander John Bower of submarine C34, who with his best friend, Noel Laurence, arrived at a party in Fareham. It was an elegant affair, gentlemen in evening dress or dress uniform and young ladies in ball gowns – the latter chaperoned by their mothers or married older sisters as late-Edwardian society demanded.

Casting his eye around the assembled company, John Bower’s gaze fell on a girl of extraordinary beauty. He quickly contrived to make her acquaintance, and he and Noel were introduced to Miss Doris and Miss Esme Coghlan White. It was Doris, the younger of the two, who had caught his eye and he spent the rest of the evening with her, under the watchful gaze of the girls’ mother. By the time carriages came at the end of the party, John was utterly smitten, and he made sure of Doris’s address so as to be able to call on her. His plan was to get to know her better and, after a respectable interval, ask her to marry him.

John Bower was the youngest son of the Bowers of Kincaldrum, a long-established Scottish family whose ancestry could be traced back directly to Henry I of England and, according to family records, as far back as Cerdic who lived 495 to 534. The name ‘Bower’ stemmed from a knight who distinguished himself in the Third Crusade by repelling a sortie of Saracens, and from who were descended the families of the Archers and the Bowers. The coat of arms of the Bowers features two bows and three quivers of arrows, with the motto, ‘Ad Metam’ – ‘To the mark’.

It was during the nineteenth century that the Bower estates were lost through the defalcations of the family lawyer, and they had to leave the ancestral home. From this time on, the Bower men had to get jobs, so they mainly joined the Navy and some the Indian Army and the family remained associated with those services thereafter. All carved out distinguished careers – at the age of fifteen, Graham John Bower joined the Navy, where he prospered and was awarded a knighthood for his services to the crown. Sir Graham married the Australian beauty, Maude Laidley Mitchell. Although, according to one of the Scottish Bowers, ‘Maude was a very stupid woman’, she captivated Graham with her stunning good looks. With her cascade of pre-Raphaelite auburn hair, she was the belle of Sydney, and ‘stupid’ or not, they were soon married. Maude may have been the princess of Sydney society, but she had a strongly religious streak and was apt to throw fits of the vapours at the slightest provocation.

The redoubtable empire-builder and his straight-laced antipodean wife had three children, James, John and Maud, and returned to England, settling at Droxford in Hampshire. John joined the Royal Navy as a midshipman, taking part in the Somaliland Expedition of 1902–04, and then, as the Navy expanded its submarine operations, he joined the new service. Not satisfied with the risks involved in early submarines, he also learned to fly in 1908, taking to the sky at a hair-raising sixty miles an hour in a flimsy aircraft which more resembled a box-kite with a motor bicycle engine on the front than anything dignified by the term ‘aeroplane’ today. The pioneering Bower alpha males led their family packs and the ladies ‘merely followed the drum’.

Doris’s family were no less colourful. Before her marriage to Francis Coghlan White, Doris’s mother Violet was a Du Croz – a flamboyant family of travellers, adventurers and entrepreneurs. They had made their fortune in Australia, Violet’s father Frederick and his brother having set up a very lucrative merchant’s business in partnership with the famous Dalgety. The Du Crozes became so successful that they owned considerable areas of Melbourne and were prominent figures in the growing city’s best social circles.

Frederick du Croz returned with his wife Margaret to England, to Sussex, where he bought a fine house, Courtlands, at West Hoathly. Margaret was a charming woman, at home in elegant society and happy to throw her money into philanthropic projects, but she had a bullish and obstinate side too. As Joan Shenton, one of Violet’s grandchildren, recalled, ‘she quarrelled madly with the local vicar, so she built a church of her own – that was the sort of person she was’. Their daughter Violet was born and brought up in Sussex and, while visiting an aunt in the Brighton area, met the Coghlan Whites. Pillars of local society, the Coghlan Whites were an equally eminent family, and it was a matter of great satisfaction to both sides when Violet married Francis, affectionately known as Cog. He took a post as District Officer in the Far East, so committing them to live abroad for some time. Cog cut a dashing figure with his dark hair and trim moustache – and with his tremendous personal charm, he was always surrounded by admiring women – however, in Violet’s eyes he could do no wrong, and his flirtations were of no consequence.

While in India, Cog contracted sprue, a tropical disease affecting the mouth, throat and digestion, which could not be cured – but could be improved by removal from the tropical climate. Violet and Cog came back and took up residence with her parents at Courtlands, where Cog, although an invalid, ran the family estate. All the same, he was frequently absent as his sister Frances accompanied him on long cruises for the sake of his health. When Margaret died, the Coghlan Whites moved to Hambledon in Hampshire, not far from Droxford.

In the early 1900s, the daughters of upper-class families were not expected to ‘come out’ into society until they were eighteen, at which time they would emerge, butterfly-like, from their cocoons. Because of Cog’s illness and frequent absences, Violet was almost solely responsible for bringing up their two daughters, Esme and Doris. Once Esme turned eighteen, Violet allowed her to put her hair up and go to balls and parties, and being unusually liberal and modern in her attitudes, she felt it unfair that sixteen-year-old Doris should be denied the same entertainment. So it was that, although technically still in the schoolroom, Doris was allowed out into society – and fate brought her together with Commander John Bower.

Bower was so smitten by the sixteen-year-old siren that he proposed almost immediately. Doris, although taken aback by the suddenness of this development, was bowled over by all the ardour and passion, and threw herself enthusiastically into the whirlwind romance. At this stage, Violet, despite her liberal, modern thinking, put her foot down. She was adamant that Doris was much too young to get engaged at sixteen, so Bower, impulsive and besotted, threatened to shoot himself. It was only with great effort that Noel Laurence dissuaded him.

Violet insisted that they have a very long engagement and not marry until Doris came of age, so eventually Doris and John were married in December 1912 – very shortly after the death of Cog. Young, glamorous, dashing, and very much in love, they lived at the centre of navy social life and Doris eagerly embraced the role of service wife, travelling everywhere with her husband. The world was their oyster.

In November of 1913 Doris Bower discovered she was pregnant – and greeted the news with less than unbounded joy. A baby would cramp her style, just when she and John were having such a wonderful time. Being pregnant would spoil her figure, and what was more, it wouldn’t be long before she would have to forego the high life and stay at home, nursing her bump.

Ursula Violet Graham Bower was born on 15 May 1914, and Doris was impatient to return to the social life she’d enjoyed before. Still only twenty-one, Doris had no intention of staying at home with the infant Ursula while John travelled and partied, but fortunately, Violet was happy to look after her grand-daughter. She joined them as live-in nursemaid in the Bower home in the Dovercourt suburb of Harwich where John was based, and Granny Violet – affectionately known by all, for whatever reason, as Humpus – took care of Ursula’s upbringing.

Ursula was three months old when the First World War broke out and Harwich, as a major submarine base, became the centre for North Sea E-boat patrols. At the age of two, Ursula’s first memory was of looking down from a first-floor window on to a bomb-crater in the seafront road in Dovercourt. Just a few doors away from the Bower home, barriers had been rigged up around it and a solitary policeman stood guard. German Zeppelin airships had legitimately targeted the naval base, but had missed, hitting instead the residential suburb where many naval families lived.

Her second enduring memory was of going to see the wreckage of a Zeppelin which had been shot down. She recalled,

It must have been the ‘Cuffley Zepp’, whose destruction was a landmark in World War I. It had been raining, and the grass was wet and brilliantly green. The wreckage lay in a field with many other visitors seeking access to it; the way in lay through a single gate. I remember my father picking me up and carrying me over the muddy and trampled entry. I remember, again vividly, blackened openwork girders towering high up above my head against a showery sky. The Zeppelin had come down in flames and I was told later that a number of the luckless crew had jumped to escape the flames. The ground was presumably soft after rain, and it was noted how extremely deep was the impression made by the Captain’s falling body.

It was at Harwich that the Bowers met Rudyard Kipling. At the time, John’s forays into writing had remained unpublished, but Kipling encouraged him and nurtured his talent. This was the start of a writing career which was to last for many years, as John wrote under the name ‘Klaxon’. Ursula would be the first to admit that much of his verse was clearly derived from Kipling’s, but his prose had a much more individual character. Whatever his style, this second career brought new influences to bear, and may have been what inspired Ursula to write in later life.

With Humpus looking after Ursula, Doris was free to enjoy the life of a navy wife – and it occurred to her that two children would be no more incommoding than one. When Ursula was two, Graham was born, and Doris looked after him a great deal of the time, while Ursula stayed mainly with Humpus. She was undoubtedly happy with her – but as she grew older she couldn’t avoid feeling that her mother had rejected her, and this conviction coloured much of the rest of Ursula’s life. Ursula’s own daughter Catriona, almost eighty years later, was brutally honest:

Mummy, from an early age was quite a plump baby and grew into a tubby toddler… she was indulged by her grandmother, and one of her cousins had an enduring memory of my mother being a plump little girl sitting on a sofa eating a box of violet creams.

Sadly, Ursula didn’t match up to Doris’s image of the ideal daughter – a petite and elfin moppet she was not.

The life of a navy family was a nomadic one, especially during the war, and in 1917 the Bowers moved to Inverkeithing in Scotland, where John served in the ill-fated K-boat submarines based at Rosyth until the end of the war in 1918. For once, Ursula was left with Doris, as Humpus returned to Hampshire. With submarine warfare still in its infancy, the K-boats were appallingly hazardous, but Bower quickly got to grips with his command of K12, and did well in what was a particularly accident-prone class.

Crews would be on exercises for unspecified periods and, required to observe radio silence, had no means of contacting their families to say when they would be home. John was away for long spells – but Doris would always be at the dockyard when he got back. Their romance had always been a very passionate one, and one might attribute Doris’s certainty as to when he would be returning to a mental resonance between them, but a strong psychic ability – a sixth sense – ran in Doris’s family. With a sudden intuition, Doris would take the rickety train from Inverkeithing to the dockyard, where the men grew accustomed to seeing the elegant figure of Commander Bower’s wife arriving at the submarine base and would comment, ‘Ah, K12 is coming home today’. And K12 would turn up, and with her John Bower – but as the war progressed, he was increasingly exhausted and stressed. Just as it was not recognised in the trenches of the Western Front, shell-shock was not acknowledged as the result of weeks cooped up underwater in a vessel of dubious reliability and under sustained exposure to enemy attack – but by the end of the war that was what John Bower was experiencing.

After a short posting in Chatham, K12 was sent to Portsmouth. In one of the most stable periods of Ursula’s early childhood, the family settled in Droxford, near John’s parents. Humpus also lived in the area, having found a beautiful Queen Anne house just across the road from Sir Graham and Lady Maude. Her home became a family hub as Doris’s sister Esme brought her children to live with her while her husband was travelling with the Navy (she was now married to John’s best friend, Noel Laurence).

With the Bower family around her, Ursula began to discover first-hand the family’s tradition for adventure. Her daughter Catriona summed up the influence that the Bower family had on Ursula’s childhood:

The Bowers were a series of alpha males – accustomed to command and quite tough cookies – good organisers and good servicemen, with a strong adventurous streak. There was all this travel, and the navy – and her great uncle [Sir Graham’s brother Hamilton] was an explorer and did some of the early surveys in Tibet. She had all those influences and lots of stories of derring-do and adventure – she was reared on Kipling and Buchan. She breathed all that in – it all passed into her system.

In Droxford Ursula came under two contrasting influences. One was Humpus, who meant well, but by overindulging Ursula’s penchant for expensive chocolates, helped to turn an already big-boned child into a large and plump one. Doris, always elegant and immaculately dressed, felt little in common with the daughter who so little resembled her. Equally certainly, Doris was unaware of the lasting sense of rejection Ursula felt.

The other influence was Sir Graham, who would take her for long walks on the Hampshire Downs. These forays awakened her interest in the ancient world and even as a little girl of six or seven she was fascinated by archaeology as a window into the past. In Sir Graham’s house the talk was always of travel and adventure. She recalled years later,

All the time there was coming and going in the house and talk of these service adventures and anecdotes of my grandfather and great uncle. One heard this sort of thing all the time, and it really was most exciting. I was bitterly resentful that I was not a boy. I can remember bursting into floods of tears at the age of three, being quite inconsolable on discovering that I couldn’t follow my father into the Navy.

Ursula and Graham grew up with cousins, Joan and Keith, and Ursula became particularly close to the latter, who was about her age. The big nuclear family was completed with plenty of dogs and at least one pony, which the children learned to ride. In addition, her father, with whom she always got on very well, enjoyed taking her out shooting and fishing. She never felt rejected by John as she did by Doris, and she loved the unashamedly boyish activities that they shared. These were tremendously formative years for Ursula, and by the time the family moved on again when she was eight, Ursula was a dyed-in-the-wool Bower. She had become a tomboy, and she was beginning to feel prevented by convention from enjoying the hereditary spirit of adventure which promised to inspire the lives of her brother and cousin.

The next move for the Bowers was to Weymouth where she first went to school – the four cousins in Droxford had previously been taught at home. From here Ursula evinced a desire to go to boarding school, most particularly Roedean, and at last some of her aspirations looked within reach. It was arranged that she would study at Roedean, then go to university – Oxford for choice – and read archaeology.

2

Roedean

Ursula loved Roedean and thrived there. Girls came to board from all over the world and she felt at home among the daughters of travellers, diplomats and aristocrats – one didn’t get to go to Roedean without having the financial wherewithal. Perched on the cliffs overlooking the sea to the east of Brighton, and backing on to the South Downs, the situation offered plenty of opportunity to enjoy the countryside – and Ursula was in her element. Here, too, Ursula was removed from the upheavals of naval family life – and from the feeling that she was second best to her brother in her mother’s eyes.

Graham too went to boarding school – which suited all concerned – and when John was posted to China, Doris went with him. Recognising the stress that sustained submarine operations inflicted, the admiralty transferred John to surface ships, but he missed the camaraderie. Captaining his new ship, he increasingly found himself alone on the bridge so, far from feeling like part of a team, he became isolated and demoralised. Former athlete, boxing champion and non-drinker, he took to the bottle. This began to affect his behaviour, and he was, as his grand-daughter would later put it, ‘messing about with other women and being impossible at dinner parties’. Before long, the unshakeable marriage was on the rocks.

John’s drinking and marital problems never stopped him from staying in touch with Ursula, and he wrote to her from all around the world from HMS Crocus. In 1927, sweltering in tropical heat, Bower wrote to the thirteen-year-old Ursula with some sound advice:

I enclose a cheque for £1. I have made it out to our DVB [Doris, currently at home], as I don’t know if you have a chequebook yet. She will cash it. Do not put it in the Savings Bank but blue it. These things are meant to be wasted on nonsense when unexpected.

Now, my dear child. I want to impress on you that you must be very good, always obedient to your good, kind mistresses at school. Always remember that your father was very, very good at school, and that your mother (if she had been to school) would have been equally good. You must always – oh, cut it out! I can’t keep it up. I’ll try something more modern. Keep your hands down and shoulders back, and don’t muck the horse’s mouth about. Keep your stockings up and always wear them a size too big because then they don’t wear out so quickly.

Once the Bowers – their marriage in tatters – returned from China, Ursula saw her mother during her holidays, when she stayed with her or Humpus, who had moved to London. There are photos in the family album of holidays in Cornwall – playing on the beach and picnicking – but Ursula still felt herself under the shadow of being second favourite child.

Ursula prospered at Roedean, where Humpus paid her fees. It was a school with a very strong academic track-record – no mere training ground for marriageable daughters of the well-to-do. As she later remembered,

You had to work. Standards were extraordinarily high. In my day it was quite difficult to get in. And moving between form and form, you were allowed one slip-up in your promotion. If you failed to get promotion in your exams at the end of the summer term for the second time, you were out. It didn’t matter if you were the head girl’s younger sister. You were out, to make room for a scholarship girl who was better than you were. There was no nonsense about it. I think it was extremely good for me too.

This was borne out by her report of September 1930, which was sent to her, chez Humpus, at 188b Cromwell Road, London SW5. It included a personal letter from her headmistress:

My dear Ursula,

I am very glad that you have done well in the School Certificate examination. It is delightful that you should have distinction in both English and French. You are also first in the school in Latin. You are fifth on the whole school list for your total marks. The details are as follows:

Scripture

Pass with credit

English

Distinction (second in school)

History

Good

Geography

Pass with credit

Latin

Good (first in school)

Greek

Fail

French

Distinction

Spoken French

Good

Arithmetic

Weak pass

Art

Pass with credit

You can now go straight ahead and specialise in Classics.

I hope you have had a good holiday.

Yours affectionately,

E.M. Tanner

Humpus, with her modern attitudes, was the very antithesis of Lady Maude. She saw Doris already separated from John and sadly recognised that reconciliation would be impossible, so she urged Doris to divorce him. She knew how much Doris still adored the errant John – and what a terrible scandal it would be if they divorced (so ghastly a social stigma was divorce at that time that, as a divorcee, Doris would be barred from such social gatherings such as Ascot), but she could not watch as John’s drinking tore them apart. Doris would never have divorced John had her mother not pushed her.

John Bower retired from the Navy in 1929 and he and Doris were finally divorced in 1932, when Ursula was eighteen – a split which left Doris and Humpus quite broke. John, as financially disadvantaged as the Bower ladies, went to live with his parents in Droxford. This was no easy home-coming, as Lady Maude disapproved of most things he did, including his drinking. John’s letters to Ursula were peppered with phrases such as ‘Her Ladyship won’t stand…’ and he cheerfully made a joke of his trying domestic situation.

Eventually John left Droxford and married his literary friend, Barbara Euphen Todd (best known for her Worzel Gummidge books for children). Ursula always got on well with her step-mother and liked her very much – as, strangely enough, did Doris. Although happier, John didn’t give up drinking, and this took its toll on his health. The divorce coincided with the general financial depression of the early thirties, so Doris had no option but to work. Only thirty-eight when they divorced, she was still a very striking and attractive woman, so to make ends meet, she took positions as companion to elderly ladies on cruises. Far from being depressed at her situation, she made the best of it and enjoyed the shipboard life.

Ursula reflected on her own situation with the benefit of hindsight:

I was at Roedean – I wanted to go to Oxford for choice, but anyhow somewhere to read archaeology, which was my passion. Then I happened to get to the sixth form just in the middle of the early nineteen thirties’ financial crisis. There was my younger brother to consider, and I was just told that I had to leave Roedean before I was through the sixth. The money had to be devoted to getting my brother through Cambridge.

Lady Maude would probably have had her ten cents’ worth about girls going to university – she would not have approved and would certainly have made her feelings known to Humpus. Educationally speaking, Ursula’s fate was sealed.

3

The Reluctant Debutante

Whether it was down to failing finances or Lady Maude’s disapproval, Ursula had to leave Roedean before she could complete her school certificate. As such a promising student, Ursula’s removal mystified her headmistress. An additional problem was that Ursula was told that she must not divulge her reason for leaving. It would have been too humiliating for such a prestigious family to own up to money troubles – so she would just have to bluff it out:

My grandmother thought the most disgraceful thing that could happen to a Victorian was to lose your money, and she absolutely forbade me when she removed me from the school to tell people that it was because we were short of money. And the school took it – because I take it I was showing promise – that it was my own lack of character and laziness. Nothing could have been more hurtful. I was so afraid of my grandmother, who was a most formidable lady, that I never dared say anything. I knew there’d be the most awful row.

As Ursula had predicted, her headmistress assumed that Ursula simply couldn’t be bothered to finish her education and was in a hurry to get out into the world, so tore her off a strip. ‘I got what we would call a “pie-jaw”, which reduced me to floods of tears, because I dared not tell her that the one thing I wanted to do was to stay on and go to university.’ Miss Tanner hoped to persuade her to stay and see her qualifications through – bandying words such as ‘wasting your talents’ and ‘a great future in front of you’, but Ursula did as she was told. Ursula was so upset she refused to go on with her classical studies, and so was also berated by her classics teacher, whom she liked very much. She too thought that Ursula was simply ‘dropping out’. In abject misery, Ursula retired to the art studio, and perhaps guessing what the problem was, the art mistress lent a sympathetic ear. Ursula remembered, ‘She just let me do nothing. I hadn’t the heart to go on with it. What was the use? It was real heartbreak, absolute heartbreak.’

Many years later she met Miss Tanner and confessed the reasons for her removal – only to be informed, ‘If you’d told us, you could have gone for a scholarship’. She was sufficiently good for the school to have paid, not only to finish her school certificate, but to put her through university too. Ursula’s life could have followed quite a different course, but for an outdated Victorian taboo.

In an interview recorded in her sixties, Ursula summed up the situation at the time, the general view of women’s lot in the 1930s, and the sad conflict with her much envied – and much loved – brother:

He wanted to go into the Navy, but there was so much cutting of defence spending at that time that my father was bitterly against it – he said there was no career in it, that he would never get through and get the full promotion, and he’d better go into a civilian occupation. My brother didn’t see that at all, and he eventually took the bit between his teeth in 1939 and went into the Marines, in which he served for quite a reasonable career. However, I was stranded – very unhappy for about five years…

It was Ursula’s great misfortune to be born a girl,

I heard it said that girls always marry. It was no good spending money on me because I wouldn’t want a career – while my brother would … but of course that isn’t so. It was purely the social attitude of the time, that women didn’t have careers. Women didn’t take jobs – not in the service families at any rate.

Crushed in her hopes of pursuing her passion for archaeology and the career she would so have loved, there was an even worse indictment inherent in the end to her education, ‘The thought that I wasn’t worth spending money on was a most dreadful thing. It was a very unhappy time.’

What was more, the financial sums didn’t add up. There was money available to educate Graham – and after Ursula had been dragged from Roedean, the family paid for her to go to finishing school in Switzerland for six months – perhaps on Lady Maude’s recommendation. Ursula enjoyed Switzerland and learnt to speak beautiful French – but returning to England, her linguistic abilities and newly acquired social sophistication were no antidote to the disappointment of life in London. Ursula was expected to live with and look after Humpus – but adoring her as she did, she set about it with as good a will as she could muster.

As etiquette required, there was no public acknowledgement that the Bower ladies were short of money – if they really were. Ursula ‘did the season’ and spent a year going to balls and social gatherings. Unlike her mother, this was not her idea of a good time. She was no longer the violet-cream-eating podge of her childhood, but she was still a generously proportioned girl and disliked having to dress up and do the rounds, making small talk. Digging up pottery shards or old bones somewhere in the country would have been more her style.

Society magazines carried photos of white-clad debutantes, engaging the camera with a confident eye. Ursula’s ‘coming out’ portraits, however, show a pretty but wistful girl, staring away from the lens, looking uncomfortable in her elaborate debutante dress. ‘The season’ was an upper-class family’s way of launching their daughters on society and getting them to all the right parties to meet eligible young men, so Ursula complied to oblige her mother and grandmother. London society was a rich hunting ground for girls with marriage in mind, and Ursula (despite having nothing further from her thoughts than matrimony) certainly met some interesting people, including James Robertson Justice, with whom she later recalled sitting on a park bench. Given Ursula’s candid and matter-of-fact character, that wouldn’t have been a euphemism for anything more intimate.

The society parties of the mid 1930s did nothing to boost the confidence of a girl much in the shadow of her glamorous mother. Ursula was now a tall, ‘well-covered’ young woman, and living with the ever-indulgent Humpus, dieting would have been out of the question. In any case, feeling rejected by her mother and thwarted in her wish for an academic career, Ursula was hardly a vain girl. Bound up in the duty of being a companion to Humpus, she got on with the job in hand, finding interests and hobbies with which to pass her time. She studied archaeology from books, and found outlets for her artistic talents in theatre and costume-design. Related to costume design, Ursula also enjoyed textiles, embroidery and calligraphy, and far from sitting and feeling sorry for herself, she kept busy. Humpus either failed to notice her grand-daughter’s discontentment with London life or, with the best will in the world, turned a blind eye. The die had been cast and there was nothing she could do to compensate Ursula for the university education she had longed for – or to cure the frustration she felt at the lack of real, Bower-standard excitement in her life.

On her occasional visits to London, Doris would take Ursula out – although this maternal attention stopped short of going clothes shopping with her unfashionable daughter. Arriving one day at Humpus’s house, svelte and immaculately dressed, Doris Bower watched with disbelief as her daughter, in her late teens, came downstairs wearing a suit more appropriate for a fifty-year-old. ‘What ARE you wearing?’ she demanded – and irrevocable damage was done. The hurt must have gone very deep, as Ursula later remembered the incident vividly to her own daughter, Catriona. She recalled, ‘Mummy was completely devastated, because no-one had ever come with her to buy her nice clothes or to think of how she was dressed.’

Looking back, many years later, Ursula assessed her relationship with her mother,

It’s a rather painful affair, but I think it’s got to go down. My mother, who was a most charming, intelligent and very, very attractive woman – a wonderful woman with a surprisingly strong character – or rather a strong moral character – great determination. What she wanted was a really attractive debutante daughter, which was a desirable thing for her generation – who would make an extremely good marriage. Careers didn’t enter into it. Career women were dull. Well, the last thing I was, was an attractive debutante. She wanted a very, very pretty girl who could dance and play tennis and golf and ride well – and what she got was me. So I’m afraid she just honestly didn’t take any trouble. She had got her own problems with her marriage.

Even so, Ursula nursed no great rancour against Humpus – for whom she felt enormous respect and affection. As for Doris, the sense of rejection still didn’t stop Ursula from wanting her mother’s approval and trying to be as good a daughter to her as she could.

Doris spent holidays with Ursula and Graham, and she would often take them to the West Highlands. Here Ursula discovered the beauty of Scotland, the love of which would stay with her all her life. Scotland brought out the psychic instincts in Ursula – certainly Doris and Humpus both had a sixth sense, which had been passed on to Ursula. On one occasion Ursula and Doris were camping in the western highlands. Graham was not with them, so the two of them were touring in a car, and as dusk fell they planned to make camp. They found a gate leading into a field on the side of a hill at the top of which were the remains of a broch – a vitrified fort. It was a very ancient, Bronze Age site, and as was the custom in those days, the defenders built walls of stone then, to make them extra strong, lit fires around the edges so that the minerals in the stone melted and turned into strong glass.

Although the gateway into the site was quite wide, it was badly rutted and they had trouble getting the car through and into the field. Closing the gate they unloaded their kit and started to pitch their tent. Ursula began to feel uncomfortable and both of them found themselves instinctively looking over their shoulders to the top of the hill. Doris wasn’t happy, ‘I don’t like this place. It doesn’t feel good,’ and at this point Ursula looked up and saw a strange, twisted shape – a contorted figure – looming down towards them from the broch above. ‘Quick! Let’s get out of here!’ They threw their kit into the car, jumped in and drove off. Going in the other direction the car fairly flew through the gate like a cork from a bottle. Neither questioned in the least what they had both seen and felt – they had both experienced the same sense of terror and they simply drove away and found somewhere else to camp.

Ursula’s special solace was her car ‘Aggie’, a hugely expensive Aston Martin. For a girl whose education had had to be curtailed due to lack of funds, this sounds an unlikely purchase, but Ursula eventually got to the bottom of the family finances:

It turned out when it was too late that my grandmother had provided savings for me which would have sent me to university – but nobody told me about those, and they were never used. I think they matured when I was about twenty-one. They were never drawn on when I really needed them, which was when I was seventeen. So when eventually I got them, I regret to say I blewed them on an extremely nice sporting car which was the joy of my life.

Ursula’s idea of a good time was to take her beloved Aggie up to the highlands and to tramp the wild country in search of archaeological relics, or to look for hill-fort remains in Dorset:

I used to go off whenever I could get away. I wasn’t awfully popular because it meant they had to pay somebody to come in and live with my grandmother and housekeep for her. I used to go off to Skye and do hill-walking all by myself in the mountains. It was lovely being back in Scotland – the Scottish feeling is very, very strong – still is. I loved that. Sometimes I used to have old school friends with me, but quite a lot of the time I was alone. I loved hill-walking. To start with I found I suffered from a certain amount of vertigo, but I didn’t like this because it interfered with my walking. So, I simply made myself go up steep slopes and risk it – and I cured myself.

Ursula found another way in which she and Aggie could escape. It was not unusual in the thirties for young women with a taste for speed and excitement to take part in car rallies. Certainly, not all of them would have had their own cars and many would have been navigators rather than drivers, but Ursula enjoyed the sport and, particularly as many of her rally partners were also women, she made sure she could deal with engine problems by taking a course in mechanics. John Bower was quite happy with Ursula rally driving – it was typical family behaviour. His only objection was raised when he found out that her current navigator was a man. This racing partnership was certainly no romance – in mentioning her new navigator to her father she referred to him as ‘the Gloomy Dane’ – but while he could deal with his little girl hunting, shooting, fishing, engine-fixing and rushing around the country in a fast car, he could not countenance her doing the latter closely closeted with a man, and they had an enormous row. Ursula protested the innocence of the partnership, and John, having a man’s instincts about the ‘GD’s’ possible ulterior motives, was furious. This caused a serious disagreement and a rift between them, and they didn’t speak for a long time – in fact it was probably the last time that Ursula saw him.

Doris, meanwhile, grew tired of globetrotting in the company of elderly ladies and married an old – and, fortuitously, extremely wealthy – family friend, Eric Patterson. This wasn’t a marriage of convenience – Patterson was a charming, kind and gentle man – and as Doris never expected to recapture the breathless passion of her first romance, she entered into her second marriage with a more measured idea of love and what made a working partnership, and this proved a recipe for lasting happiness.

With both parents resettled, Ursula remained with Humpus in London. With no prospect of her life changing, Ursula grabbed every opportunity to escape, especially loving her trips to Skye: ‘That was bliss. Every year I used to go and stay in a farmhouse near Bla Bheinn at Torrin on Loch Slapin – go up for about six weeks every summer.’

On her holiday to Skye in 1937 Ursula met Alexa Macdonald – the only other guest at the small family bed-and-breakfast. She, like Ursula, loved the highlands and the great outdoors, and both jumped at the opportunity to go out with the local crofters on a night-fishing trip on Loch Flavin. Wrapped up against the summer evening chill, they sat in the small Hebridean fishing boat and watched the spreading wakes ripple the moonlit surface of the bay as they cast off. Ursula always remembered that night, the huge black mountains of the Barlam Range towering over them, the enormous full yellow harvest moon and the water like black glass, without a breeze to disturb it. Between hauling in bucketfuls of mackerel until after midnight, the girls got talking and, hitting it off at once, they spent the rest of their holiday hill-walking together. Their walks and picnics afforded plenty of opportunities to discuss their hopes and aspirations, and Ursula confessed her longing to travel. She wanted to go somewhere wild and untouched, and explore for herself a different culture, rich in history and tradition. It was a wistful notion – as things were, Ursula could envisage no turn of events which could break the routine of her life in London.

Ursula’s photos from the holiday show more of the wide-open spaces and local landmarks than people and faces, but there are some snaps of their hosts at the farm. To them these two young ladies must have painted an unconventional picture of modern femininity – but judging by their warm smiles in Ursula’s album, they were won over by the townies’ unaffected manners and their enjoyment of their island home. By the end of the holiday a great friendship had been cemented. The girls exchanged addresses and promised to stay in touch.

4

From Kensington to India

Ursula settled back into her household routine with Humpus, where the immediate prospect was of autumn, then winter in London, with little chance of escape. As she acknowledged, ‘Kensington is not what I would call a terribly exciting area for a young woman of rather adventurous tendencies.’ Then in autumn, a letter arrived from Alexa inviting her to India. It was a gift from heaven. Alexa was going out to housekeep for her brother who was in the Indian Civil Service, and she wondered if Ursula would like to keep her company through the winter.

Ursula admitted she had no idea what she was going to. ‘Of course, I jumped at this, and I may say I thought of India entirely in terms of the Taj Mahal and Delhi.’ It was an opportunity not to be missed, and surprisingly, even the family responded with enthusiasm to the idea, despite the fact that alternative arrangements would have to be made to look after Humpus. The cause for this soon became clear as one of her mother’s friends pointed out gleefully, ‘My dear, you never buy a girl a return ticket to India’. Girls were shipped out to India with a view to finding a husband, and Ursula was under no illusions as to the reason for her mother’s enthusiastic support. ‘By this time I was pretty well on the shelf. I think my mother saw me off with the light of hope in her eye.’

Ursula set about gathering together suitable clothing for the trip and, methodical and inclined to make lists, she jotted down items she thought would be essential:

3 pants, 2 evening frocks and coats, 1 slip, 1 nightdress, 1 pyjamas, 1 pyjama belt, 4 scarves, 2 belts (elastic), 2 bras, 1 bed-jacket, 2 shirts, 2 frocks, 1 pant, 3 handkerchiefs, 1 face towel, 2 shorts, 2 silk frocks [this latter was struck through on better consideration]

Eventually the day came for Ursula to leave London, and wanting to preserve every memory of the forthcoming adventure, she started a diary:

Saturday 25 September

Breakfasted 8.30 and finished packing. Mother and Graham came round about 10.45, found me still busy. Feel rather awful about going. Set off in rain for Euston. Taxi took long way round, but caught train. Aunt Mary came to see me off, brought proof of Yiewsley photo. Baby in carriage – would spit. City of Marseilles not bad boat, quite clean, but native cabin boys. Mother left before boat sailed to catch 5.20 train. Felt very miserable at final parting. Cabin mate elderly Mrs Whitehouse. Quite friendly so far. Unpacked while boat sailed; dinner and early bed.

Ursula brightened up the evenings aboard ship by fortune-telling for her fellow travellers, using a deck of cards. Ursula had known for some time that she shared the sixth sense which ran in her mother’s side of the family – so it was just an extension of this to pick up fortune-telling with cards under the instruction of Humpus’ housemaid back at home. Ursula was blasé about her talent, and regaled her fellow passengers with whatever predictions came naturally to her. On one occasion she foresaw a windfall of money – which the would-be recipient pooh-poohed as impossible, and the groundswell of opinion was that Ursula was picking ideas from the air and saying what she thought people would like to hear. Convinced of the accuracy of her predictions, she gave up the card sessions – partly due to her co-passengers’ reaction – but also in case she foresaw anything more sinister. Her confidence in her predictions was entirely vindicated when the girl wrote to her later, confirming a surprise legacy.

For a British woman travelling alone, and speaking no Hindustani, the journey by a series of trains and boats to the railhead at Dimapur was a daunting one, but at last, in late October, she arrived. As the crowds dispersed and the dust of the station cleared, Ursula looked around her – and with a surge of relief spotted Alexa. Ursula’s impressions of that first journey into the unknown were to stay with her all her life:

The car hummed on, round steeper bends, between bamboos, through lighter, drier forest – the hazy plain falling lower and lower behind – and up the feet and knees of the great Barail Range itself.

A group of hill men scattered before us and stood on the roadside, staring. They were not the slim-built Assamese of the low ground. The sight of them was a shock. Here were the Philippines and Indonesia. Bead necklaces drooped on their bare, brown chests, black kilts with three lines of cowries wrapped their hips, and plaids edged with vivid colours hung on their coppery shoulders. Tall, solid, muscular, Mongolian, they stood, a little startled as we shot by.

Many years later, in 1985, her wonder and enchantment were undimmed by time:

I must have sat there like a fool, gaping. Illumination so plain, so known and obvious, that I was speechless at my own stupidity in not remembering sooner. And suddenly, in the split second before it reached full consciousness, the knowledge was gone. It vanished as cleanly and completely as writing wiped off a slate. The car swept on up the twisty road, and I sat there dumb in the back seat, trying to snatch from the edge of my mind the vital, the intensely important thing which a few seconds earlier had been so clear. I never did.

Later, with better knowledge of the region and the local tribes, she could have identified the men as Nagas of the Angami tribe – but at the time she saw only the four distinctive tribesmen. She recalled the vivid colours of their woven plaid cloths – a sudden flash of something timeless and intriguing:

Just one look and they were gone – and I was left with my head fairly going round, wondering what on earth had happened to me. I knew Nagas – I was certain I knew Nagas. I just didn’t know where I was.

En route for Imphal to the south, Ursula and Lexie paused for refreshment at Kohima, the administrative capital of the Naga territory – but her memories of this are sketchy. She stared away to the mountain ranges beyond the town to the east, to unmapped lands, accessible only by bridle-roads, winding down the bare spurs in big, looping folds. Hills stretched away into the hazy distance – an ocean of peaks with wild forests covering steep clefts and gulfs. ‘That landscape drew me as I had never known anything do before, with a power transcending the body – a force not of this world at all…’

The next morning Ursula surveyed her surroundings. Imphal was the main town of Manipur State, which occupied the plain and some of the mountainous region between Assam and Burma. What she saw was a pleasant backwater, whose one long road to the railhead effectively cut it off from the rest of the province, and where a single mule-track opened up the route to Burma to the east. Imphal was a comfortable little British garrison with a company of military police – the Assam Rifles – along with two civil service officers, the Political Agent and Alexa’s brother, Ranald Macdonald, who was the junior, with an engineer and a doctor – and that was it.

In true British Raj style, the flavour of suburban England had been painstakingly recreated with tiled bungalows and gardens full of snapdragons and lupins among the native bougainvillea bushes. Beyond the European settlement the crumbling and dusty bazaar sprawled away towards the locals’ domain – a huge area of bamboo huts forming a mass of villages among the lush, dank greenery and many ponds across the plain.

For the British, life in Imphal ticked by at a leisurely pace and the local amenities provided sedate entertainment. There were shady lawns, golf at the ‘Club’, tennis at the Residency, and the men went shooting duck on the lakes to the south. Although Ursula was a proficient shot, it was not expected that she would join them, so she accompanied the memsahibs instead. ‘We womenfolk idled comfortably. We shopped at the Canteen, we dined, we visited the Arts and Crafts showroom, and twice a week we went to watch the polo.’