Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: ONE

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

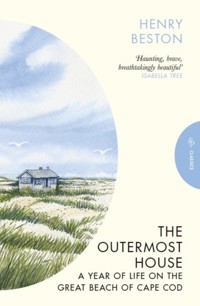

A rediscovered classic of American nature writing: the poetic account of a solitary year observing the wild beauty of Cape Cod With an introduction by Philip Hoare A fragment of land in open ocean, the outermost beach of Cape Cod lies battered by winds and waves. It was here that the writer-naturalist Henry Beston spent a year in a tiny, two-roomed wooden house built on a solitary dune, writing his rapturous account of the changing seasons amid a vast, bright world of sea, sand and sky. Transforming the natural world into something mysterious, elemental and transcendent, Beston describes soaring clouds of migrating birds and butterflies; the primal sounds of the booming sea; luminous plankton washed ashore like stardust; the long-buried, blackened skeleton of an ancient shipwreck rising from the dunes during a winter storm; a single eagle in the endless blue. With its rhythmic, incantatory language and its heightened sensory power, The Outermost House is an American classic that changed writing about the wild: a hymn to ancient, eternal patterns of life and creation. Henry Beston (1888-1968) was born in Quincy, Massachusetts and educated at Harvard. He wrote many books in his lifetime, including a memoir of his years in the volunteer ambulance corps in the First World War, an account of life in the US Navy and a book of fairy tales. The Outermost House, widely considered his masterpiece, was published in 1928. His Cape Cod house was named a National Literary Landmark in 1964, and it was destroyed by a huge winter storm in 1978.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 256

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Beston reminds us of the transformative power of nature, its ability to heal, renew and sustain… Haunting, brave, breathtakingly beautiful’

ISABELLA TREE, AUTHOR OF WILDING

‘A colorful and ever-changing chronicle of movement that approaches the magnificent’

BOSTON TRANSCRIPT

THE OUTERMOST HOUSE

A YEAR OF LIFE ON THE GREAT BEACH OF CAPE COD

HENRY BESTON

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY PHILIP HOARE

PUSHKIN PRESS CLASSICS

To Miss Mabel Davison and Miss Mary Cabot Wheelwright

Contents

Introduction

It’s a long walk in winter from Nauset Coast Guard Station to the end of the Eastham bar, a sandy spit that echoes the great arm of Cape Cod, held out into the Atlantic from the coast of New England. The sea here is navy blue; the sky the colour of a cormorant’s eye. Yet as I trudge along the beach with my friend Dennis Minsky, a naturalist and writer, on a freezing January morning, we seem to enter a microclimate. The bitter wind drops and the sun gains strength. The beach starts to seem less bleak. And we don’t feel alone. Perhaps it’s the birds that hover overhead. Or perhaps there’s a third person walking with us.

For a few years in the 1920s, Henry Beston knew this place better than anyone else. He endured its winters and luxuriated in its summers, and he observed that this strand was often a few degrees warmer than the rest of the Cape. But it is still stripped back by the cold today, pared to its bones. The beach rises ahead of us, not flat, but rolling like the great waves falling on the shore, fit to pile up more barriers they can break down.

In 1925, Beston bought fifty acres of duneland here, inspired to build what he thought would be a summer house on the site. He called the two-room, twenty by sixteen foot cedar-shingled hut “The Fo’castle”, as if it were more ship or ark than house. In September 1926 he went there for two weeks—and stayed for a year. “The world today is sick to its thin blood for lack of elemental things, for fire before the hands, for water welling from the earth, for air, for the dear earth itself underfoot’, he would write. He hoped to reconnect himself here, ‘to know this coast and share its mysterious and elemental life”. He left in the late summer of 1927, in “the year at high tide,” as he called it.

All signs of his tenancy have since been erased by those tides and storms. The dunes themselves have raised and lowered, tethered only by their grasses and shrubs, whose roots, as Beston observed, bind the sand itself, weaving invisibly below the thin crust that forms on the wind-blown sand. Compass grass earns its name, as its dead strands flicker and circle in the breeze, tracing its own radius like a raked Japanese garden.

Strewn above the high water mark are huge pieces of timber, tossed there by the waves; logs that might have floated here from the Gulf of Maine, as Beston recalls, or lumber from ancient shipwrecks, in a sea still echoing with the voices of long-drowned sailors that Marconi—whose early radio station was set on the nearby cliffs—believed he could record from the ether. At one point in his book, Beston reports an entire ship revealed in the sand, a Mary Celeste sailing out of the dunes. The sea spits it all out. In the local museum at the Highland Light, up the shore at Truro, a row of assorted chairs salvaged from different wrecks stand against the wall, as if waiting for their owners to resume their seats. The Cape has always been a haunted place.

Life is hardscrabble. The tracks of horned larks run side by side with coyote paw prints. Half buried in the dead tufts of turf are the carcasses of eiders and herring gulls; the beach as cemetery. Close to where Beston’s hut stood is something truly strange: a desiccated, primeval sturgeon, all grey spines and plates, a prehistoric monster cast up by the sea. It points its bony snout out to the water, waiting to regenerate. We might have been standing here twenty thousand years ago—if it weren’t for the fact that this land didn’t exist until then, when the Laurentide ice sheet that formed it began to retreat in the Pleistocene.

Time compresses, speeds up. We scratch about in the sand by the great pooling inlet that floods out from the marsh to the sea, emptied and filled twice a day by the tide, but we can’t find any trace of Beston’s hut. Dennis saw the last of it, in the great storm of 1978 that finally pulled it apart. It had been successively moved back, in retreat from the rising sea, but the sea would have its bones. Dennis remembers seeing a few scattered planks, the last residue of Beston’s investment in this place.

It is a calm enough scene on this winter’s day. It is hard to even remember that the world beyond this beach exists. Everything seems concentrated to this here, this now. But strangely enough, the violence of the taking of the Fo’castle seems a mirror of what brought Beston here in the first place. This battlefield of the elements was a kind of sympathetic magic; it drew Beston away from the memory of recent trauma.

* * *

Henry Beston Shearan was born in Quincy, Massachusetts in 1888. His father was a doctor of Irish descent; his mother, a French Catholic. He was educated at Harvard, but was drawn to France—his mother died when he was eight years old—and he later studied at the University of Lyon. He was a handsome, broad-chested young man—he looks like an American football player in early photographs. In others he wears a dandified double-breasted suit, complete with beret. In 1915, he joined the French army, and served as an ambulance driver on the Western Front. In the last year of the war he joined the US Navy as a press representative.

In what seems like a strange transition, after the war he would begin writing fairy stories—The Firelight FairyBook (1919) and The Starlight Wonder Book (1923). But perhaps these were a reaction to his wartime experiences, in the way that the war itself had seen a remarkable rise of belief in faeries, angels and other aspects of the supernatural. In a way, Beston’s precise but romantic writing turns the Cape into a kind of fantasy; a retreat into nature and sun worship. Beston found a kind of solace there. He was a man who had returned from the First World War in which he’d worked as an ambulance driver, picking up the deadly flotsam and jetsam of an industrial war that had turned the land into an awful perversion of the natural world: the Western Front had become a terrible heaving sea, coursed by tanks, called land ships, patrolled by men in gas masks like aqualungs, and shellholes flooded with fetid water in which they might drown.

Beston saw many men die. At one point he has a conversation with a young soldier on guard duty about how the war is proceeding. Moments after Beston walks away, a shell falls and he watches as the soldier seems to inflate like a balloon, then falls back, imploded. “A chunk of the shell had ripped open the left breast to the heart. Down his sleeve, as down a pipe, flowed a hasty drop, drop, drop of blood that mixed with the mire.”

Later, Beston is taken even nearer to the front line. “No Man’s Land had widened to some three hundred feet of waving furze,” he wrote, “over whose surface gusts of wind passed as over the surface of the sea. About fifty feet from the German trenches was a swathe of barbed wire…. Upon this mist hung masses of weather-beaten blue rags whose edges waved in the wind. ‘Des camarades’ (comrades), said my guide very quietly.”

The memory of rotting men caught like crows on a barbed clothes line must have induced elements of what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder in the writer. Beston left that horror behind for this utopian vision, this New England—only to find a new place of loss. The shipwrecks he witnessed, the life and death struggle of the beach, the bulwark of the Cape itself; they all seemed to bridge the living and the dead.

The nearest humans to the Fo’castle are the young surfmen who staff the lifeguard station—most of them Cape-born. They’re soldiers of the sand and sea, patrolling the dunes in all weathers: in fog and sun and blinding sandstorms and drifting snow that obscures all landmarks. Beston keeps hot coffee on his hearth should he hear his friends’ footsteps at any time of night as they call in to see if he is OK. In the bleakest winter, he sees them carrying their lanterns in the desolation, looking out for lost souls. “Those lights along the surf have a quality of romance and beauty that is Elizabethan,” he says, “that is beyond all stain of present time.”

There is a purity here, where humans, their technologies and their wars, do not hold dominion. Beston writes of wanting to see a tempest sweep over the Cape, noting that there, as in England, the word has the same meaning as the title of Shakespeare’s play. Perhaps he is a Prospero, conjuring up phantasmagorical effects on his island of strange noises. “The tempest,” says Melville, “bursting from the waste of Time.” Indeed, Beston talks about leaving his friends “on shore,” as if his sandy spit were isolated by time and space. For this Europhile American, the Cape’s New Englishness still looks back to old England in its names—Truro, Chatham, Wellfleet—as though they were more connected by the Atlantic than separated by it.

Even now this land hardly seems land at all, let alone part of modern America. The Outer Cape is set thirty miles out into the Atlantic. It is another frontier in another time, a newly invented land, at least from a western point of view. The Nauset people had lived here first, alongside the Wampanoag—their name meant People of the Dawn, since this is where first light rises over New England. When the Europeans came, in the seventeenth century, they found it a difficult place to settle. In November 1620, the Pilgrim Fathers made first landfall here on the Cape (having left my hometown of Southampton), in what we now call Provincetown Harbour. They stole Indian seed corn, did their washing, and moved on to the mainland across Cape Cod Bay.

Fitfully scattered with homesteads and fishing villages, this remained a remote, appropriated, primordial place then, still coming into being. On his numerous walks through Cape Cod in the 1840s, Henry David Thoreau declared it a place where a man might put all America behind him. A century later Sylvia Plath, who had spent her childhood summers on the Cape, returned to this beach for her honeymoon with Ted Hughes. It may have been the only happy seven weeks of their life together, that summer of 1957, when the “great salt tides of the Atlantic” had set “the sea of my life steady”, as Plath wrote. Yet it would appear later in her darkest poem, “Daddy”, in which the waters off Nauset offer a sole glimpse of natural beauty: those blue-green waters that might have saved her.

I’ve been visiting the Cape for nearly twenty years; I too have lived in a wooden house on its beach, with the sea rushing under its foundations. I’ve felt the house shaking in a nor’easterly—Beston claimed that in one such storm, in his hut, he nearly died, once or twice. I’ve realized that you never make friends with the Cape, only an alliance. I’ve become familiar with it, but forever surprised by it. By its beauty and its bleakness.

You come to a dead end here. (Provincetown, at the Cape’s tip, boasts a car bumper sticker—“The Last Resort”.) Or perhaps a living beginning. This is where the sea starts, its waters swarming with whales, sharks and seals and sand lances and bluefish, with diving gannets and primeval cormorants and punk-crested mergansers and sturdy eider ducks that seem to hold the sea together as they float in rafts, apparently impervious to the freezing cold. They coo at me as I swim in those winter waters—whether from disapproval or approval, I’m not quite sure.

In a rhapsodic episode in his book, Beston watches a handsome young man strip and dive into the surf, emerging with a smile on his face. Beston puts himself, and his reader, in the place of the diver, in the way that you have to place your body, through his book, in this place. The Cape is sensual and unforgiving. It takes your breath away, in every sense, because it is a sensory overload. It is elemental because you cannot help but be part of the elements here. Beston knew as much. He came here in Thoreau’s footsteps, as if following them in the sand, and built himself a hut. His seaborne, sand-borne version of the philosopher’s house on the shores of Walden Pond performs the same monastic function. Like Thoreau, his account of his stay would define him ever after. But Beston was already following in a Cape tradition.

Life-saving huts had been set up on this coast here since the eighteenth century, for those cast up on these bleak shores—a sailor might survive a shipwreck here, only to die of exposure, with no hope of reaching habitation. The huts held supplies, and offered shelter. Later still, beachcombers and isolatoes—as Herman Melville called the inhabitants of the Cape and its islands, Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard—built dune shacks out of driftwood and the remains of those wrecks whose timbers still stick out of the sand. Their shanties might as well be constructed from seaweed. In Moby-Dick, Melville jokes the inhabitants of Nantucket are so much of the sea that little clams can be found clinging to the undersides of their tables and chairs.

The dune shacks, like Beston’s Fo’castle, were self-sufficient, drawing water from wells in the sand and, nowadays, energy from the sun via solar panels. Their inhabitants are Beston’s heirs. Their boards and shingles speak of an interwar bohemianism, of nude sunbathing and a worship of the sun and the sea as an antidote to what had gone before. Some of them still stand, on the back shore, precious heirlooms passed down from hand to hand, withstanding attempts to demolish them, either by the authorities, or by the elements. Others have collapsed into the sea, like the cottage converted from a life-saving station by the playwright Eugene O’Neill at Peaked Hill Bars which, according to a report in the local paper, the Advocate dated 8 January 1931, “took a long slide into Davy Jones locker today,” as the “boiling surf” pounded away at its flimsy foundations.

O’Neill had long since gone, but his neighbours still remembered how he’d row alone into the sea, “taking the most reckless chances … in a ‘Kiyak’ or Eskimo light skin canoe.” There’s a sense that the Cape’s more remote settlements, their shingled houses with their neat-fitted drawers and cupboards, standing on stilts over the sand that itself is forever shifting, might yet survive the great flood, when it comes. In January 1933, two years after O’Neill’s hut fell, the Fo’castle teetered at the edge of a broken dune. Beston dashed back to retrieve what he could, before it fell into the sea, as the high tide came to within a foot of the door. But miraculously, it was preserved, moved back and “still monarch of its sand dunes,” as he wrote in a letter to the New Bedford-Standard Times.

The shipwrecks that Beston witnesses are not only a reminder of his recent past, but of all time, past, present and future. He sees them almost in slow motion. He watches a vessel break up, with no hope of saving the crew. “One great sea drowned all the five…. the whole primitive tragedy was over in a moment of time.” A week later, one of the surfmen finds a hand sticking up out of the sand. The wreckage trembles in the surf. The accumulated remains of that winter and many others lie packed in the dunes, “like fruits in a slice pudding.”

This vast, harsh landscape is paradoxically soft and fragile. Beston sees himself within it, not as an heroic challenge, but as an assimilation and a sublimation. He joins this place, knowing he is only a temporary part of it. Little wonder the Native Americans laughed at the pale incomers when they tried to buy this land; how could anyone own a place that is clearly part of something so much greater than the human?

And so Beston becomes part of the beach, the sea, the dunes, watching them as they change through the seasons. His book is an almanac. In the winter he sleeps on his couch by the windows, feeling part of the outside, in an observatory or wheelhouse. He is feral, nocturnal, tidal, tugged by the moon and the stars. He kicks the phosphorescent sea into a scatter of stardust, and walks under the “westing of the moon.” The constellations—the Pleiades and Orion—are the graphic markers of the passing seasons; they’re where stories began, as John Berger said. Beston peers at the night sky and sees “the whole earth is dark, dark as a shallow cap.” In the sharpness of the Cape winter, which can stretch into April and even May, “there is a blueness in the air, a blue coldness on the moors … Winter is no mere negation, no mere absence of summer; it is another and a positive presence.”

Beston is human in his reactions but pulls out of his time and space to see this place as if from outer space, like an astronaut. His distance—even in his closeness—allows him to experience it all the better, in the way that Thoreau saw the whole ocean in Walden Pond. “How is it that we can ignore the drama of the sun,” Beston says, “the great natural drama by which we live … not to share in it, is to close a dull door on nature’s sustaining and poetic spirit.”

And its greatest drama is always the sea, because it is always there. The tides determine what and how Beston sees the world. They cast up horseshoe crabs at his feet, and change the light itself; the reflecting mirror of his Cape existence. The sea-sounds augur and echo the seasons—“Men hear the coming winter in the roar.” Storms thrill him, the sea “a strange underbody of sound when heard through the high, wild screaming of a gale.” Joseph Conrad wrote in The Mirror of the Sea that “some of us … have seen it looking old, as if the immemorial ages had been stirred up from the undisturbed bottom of ooze … If you would know the age of the earth, look upon the sea in a storm.”

Beston has stepped outside time. He senses the passing of the world through the fibre of the Cape; the way it receives life and death, and is animated by that energy. The dead birds frozen on the beach; the living ones that scrape by in winter. Beston calls them “ocean peoples,” and their sentinel spirits provoke the most celebrated passage from his book, one which yearns for a reconnection with the natural world.

“We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals,” writes this highly moral, innocent man. “Remote from universal nature, and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion.”

Beston’s spell on the Cape—and it is an enchantment—allowed him to see out of that dark glass, and across the distance between us and other species which Berger called “the narrow abyss of miscomprehension.” They are the real faeries, his familiars. “They are not brethren, they are not underlings,” says Beston; “they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.” This was the legacy of his house at the end of the world. Through its windows he bore testament to unmemorialized animals, ordinary humans, a shifting, abiding landscape, a rising, roaring sea. How could he ever forget it? How could anyone ever forget it? In a way, the spell was too powerful.

It was only having left the Cape that Beston was able to write about it. As the naturalist and writer Robert Finch says in his perceptive 1988 introduction to Beston’s book, “he had to leave the place where he found his vision in order to convey it to us.” As Finch notes, when Beston proposed marriage to the writer Elizabeth Coatsworth, best known for her own nature writing, she agreed only on condition that he should write his book first. The Outermost House was published in 1928, and they were married the following June. The couple lived in a farmhouse in Nobleboro, down east in Maine, as it is known, where they brought up two daughters. Beston wrote other books—Northern Farm, Herbs and the Earth—but none achieved the success of The Outermost House. He donated the Fo’castle to the Massachusetts Audubon Society in 1959, and returned to the house for the last time in October 1964, when it was dedicated as a National Literary Landmark.

Henry Beston died on 15 April 1968. His house only outlived him by ten years. It was washed away in the storm of 6–7 February 1978, and its lonely beach was returned to the birds. What lies there now is unchanged, and utterly changed. Its shores are now patrolled by great white sharks that have, in recent years, taken human lives; their shadows haunt the sands in the way of all the lost. The shipwrecks still emerge. The whales and birds still migrate. The human summer visitors come and go. And when they leave, the hard shoulder of the year takes over. The wind whips in your face, and the cold bites your skin, and the old-new land and sea show themselves once more. Fugitive, mortal, beautiful. Nothing human at all.

How could anyone ever forget such a place?

Foreword to the 1949 Edition

With the appearance of this edition of The Outermost House, the book celebrates its twentieth anniversary and an eleventh printing. The text is unchanged, remaining what it was when first set down in long hand on the kitchen table overlooking the North Atlantic and the dunes, the little room full of the yellow sunlight reflected from the sands and the great sound of the sea.

It is the privilege of the naturalist to concern himself with a world whose greater manifestations remain above and beyond the violences of men. Whatever comes to pass in our human world, there is no shadow of us cast upon the rising of the sun, no pause in the flowing of the winds or halt in the long rhythms of the breakers hastening ashore. On the outer beach of the Cape, the dunes still stand in their barrier wall, seemingly much the same, but to the remembering eye somewhat reshaped by wind and wave. The little house, to whom the ocean has been kind, has been compelled by the hurricane winds to find a better foundation and build a new chimney, else all is with it as before. At the Coast Guard Station there are new activities and new faces, and the visitor will find there sons of the very men mentioned in this book. With such changes, however, the dune world is not concerned. In that hollow of space and brightness, in that ceaseless travail of wind and sand and ocean, the world one sees is still the world unharassed of man, a place of the instancy and eternity of creation and the noble ritual of the burning year.

As I read over these chapters, the book seems to me fairly what I ventured to call it, “a year of life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod.” Bird migrations, the rising of the winter stars out of the breakers and the east, night and storm, the solitude of a January day, the glisten of dune grass in midsummer, all this is to be found between the covers even as today it is still to be seen. Now that there is a perspective of time, however, something else is emerging from the pages which equally arrests my attention. It is the meditative perception of the relation of “Nature” (and I include the whole cosmic picture in this term) to the human spirit. Once again, I set down the core of what I continue to believe. Nature is a part of our humanity, and without some awareness and experience of that divine mystery man ceases to be man. When the Pleiades and the wind in the grass are no longer a part of the human spirit, a part of very flesh and bone, man becomes, as it were, a kind of cosmic outlaw, having neither the completeness and integrity of the animal nor the birthright of a true humanity. As I once said elsewhere, “Man can either be less than man or more than man, and both are monsters, the last more dread.”

The author wishes to thank most gratefully the friends at Rinehart and Company whose good will makes possible this new edition of his book. He also wishes to thank, and again most gratefully, that staunch and discerning friend of those who write about Nature in America, Professor Herbert Faulkner West of Dartmouth College.

HENRY BESTONJanuary, 1949

CHAPTER I

THE BEACH

—I—

EAST AND AHEAD of the coast of North America, some thirty miles and more from the inner shores of Massachusetts, there stands in the open Atlantic the last fragment of an ancient and vanished land. For twenty miles this last and outer earth faces the ever hostile ocean in the form of a great eroded cliff of earth and clay, the undulations and levels of whose rim now stand a hundred, now a hundred and fifty feet above the tides. Worn by the breakers and the rains, disintegrated by the wind, it still stands bold. Many earths compose it, and many gravels and sands stratified and intermingled. It has many colours: old ivory here, peat here, and here old ivory darkened and enriched with rust. At twilight, its rim lifted to the splendour in the west, the face of the wall becomes a substance of shadow and dark descending to the eternal unquiet of the sea; at dawn the sun rising out of ocean gilds it with a level silence of light which thins and rises and vanishes into day.

At the foot of this cliff a great ocean beach runs north and south unbroken, mile lengthening into mile. Solitary and elemental, unsullied and remote, visited and possessed by the outer sea, these sands might be the end or the beginning of a world. Age by age, the sea here gives battle to the land; age by age, the earth struggles for her own, calling to her defence her energies and her creations, bidding her plants steal down upon the beach, and holding the frontier sands in a net of grass and roots which the storms wash free. The great rhythms of nature, today so dully disregarded, wounded even, have here their spacious and primeval liberty; cloud and shadow of cloud, wind and tide, tremor of night and day. Journeying birds alight here and fly away again all unseen, schools of great fish move beneath the waves, the surf flings its spray against the sun.

Often spoken of as being entirely glacial, this bulwark is really an old land surfaced with a new. The seas broke upon these same ancient bounds long before the ice had gathered or the sun had fogged and cooled. There was once, so it would seem, a Northern coastal plain. This crumbled at its rim, time and catastrophe changed its level and its form, and the sea came inland over it through the years. Its last enduring frontier roughly corresponds to the wasted dyke of the cliff. Moving down into the sea, later glaciations passed over the old beaches and the fragments of the plain, and, stumbling over them, heaped upon these sills their accumulated drift of gravels, sand, and stones. The warmer sea and time prevailing, the ice cliff retreated westward through its fogs, and presently the waves coursed on to a new, a transformed and lifeless, land.

So runs, as far as it is possible to reconstruct it in general terms, the geological history of Cape Cod. The east and west arm of the peninsula is a buried area of the ancient plain, the forearm, the glaciated fragment of a coast. The peninsula stands farther out to sea than any other portion of the Atlantic coast of the United States; it is the outermost of outer shores. Thundering in against the cliff, the ocean here encounters the last defiant bulwark of two worlds.