Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'Dan Morrison has unearthed a fabulous true-crime story and embedded it within a fascinating work of micro history. David Grann has competition.' - Robert Twigger, author of Walking the Great North Line A crowded train platform. A painful jolt to the arm. A mysterious fever. And a fortune in the balance. Welcome to a Calcutta murder so diabolical in planning, modern in conception, and cold in execution that it made headlines from London to Sydney to New York. In The Prince and the Poisoner, Dan Morrison unravels the gruesome tale of two warring brothers, set amidst the febrile atmosphere of Jazz Age India. It is the story of a city and an empire on the cusp of cataclysmic change, capturing a moment when centuries-old assumptions and expressions of power become forever altered for Indians and Englishmen alike. Moving at the pace of a thriller, Morrison's investigation of a riveting fratricide among India's rural aristocracy pulls the reader on a journey from Calcutta to Bombay, through feudal estates, viceregal balls, police interrogation cells and colonial courtrooms – a world of movies, dancing, protest and revolutionary violence.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 340

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Mac and Ida

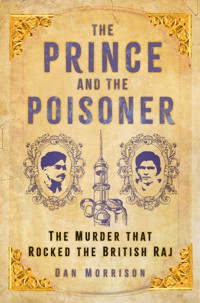

Cover illustration: New York Daily News

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Dan Morrison, 2024

The right of Dan Morrison to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9605 9

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Cast of Characters

1 Every Inch an Aristocrat

2 These Jealous Impulses

3 The Nervous Bhaiya

4 As Meat is Dangerous for the Child

5 The Viper’s Tooth

6 Savour of Self-Interest

7 A Specially Virulent Strain

8 Taut

9 I Will See You, Doctor

10Cito, Longe, Tarde

11 Squirming Rats

12 The Poisoned Spear

13 When a Man Becomes Desperate

14Boro Ghori

15 Like Something Out of a Foreign Novel

16 Hello!

17 People of Position and Money

18 Forward Under Custody

19 This Smart Set

20 Practically Nil

21 Best of Brothers and Friends

22 A Chota Peg

23 No Proper Trial

24 Vendetta

25Rajbansha

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Notes

Bibliography

Cast of Characters

The Accused

• Benoyendra Chandra Pandey: The charismatic Raja of Pakur, a fiefdom bigger than modern New York City; zamindar ruling over thousands of impoverished farmers and tribals; aspiring film producer. Elder half-brother to Amarendra Pandey.

• Taranath Bhattacharjee: Small-time doctor, part-time vaccine maker, and former student at the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine. Friendly with Benoyendra’s mistress, the actress and dancing girl Balika Bala.

• Sivapada Bhattacharjee: Assistant professor at the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine; former professor of Taranath (no relation); and consulting physician to members of the Pakur Raj clan and other well-to-do families.

• Durga Ratan Dhar: A member of Calcutta’s medical elite and a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians.

The Victim

• Amarendra Chandra Pandey: The 22-year-old heir, with his elder half-brother, to the Pakur Raj estate. On the verge of seeking a formal division after years of suspicion that Benoyendra is looting their shared patrimony.

The Law

• E. Henry Le Brocq: Deputy police commissioner in charge of Calcutta’s detective department. A genial, aggressive lawman.

• Saktipada Chakrabarty: Assistant police commissioner who launched the Pakur investigation following a secret meeting with Kalidas Gupta (see below).

• N.N. Banerjee: The popular public prosecutor trying his biggest case yet.

• Barada Pain: Wily politician and defence lawyer; future scandal-scarred member of Bengal’s wartime Cabinet.

• Thomas Hobart Ellis: Sessions judge and future governor of East Pakistan.

• John Rolleston Lort-Williams: Justice of the Calcutta High Court, and a former Conservative Member of Parliament from south-east London.

• Syed Nasim Ali: Justice of the Calcutta High Court; future chief justice.

The Family and its Affiliates

• Protapendra Chandra Pandey: The late Raja of Pakur, and a supporter of the militant Bengali underground. Died in 1929 of a bacterial infection.

• Rani Surjabati Devi: Aunt and surrogate mother to Benoyendra, Amarendra, and their two sisters; Amarendra’s chief protector; target of Benoy’s machinations.

• Srimati Pritilata Devi: Benoy’s petite, long-suffering wife.

• Prosunendra Chandra Pandey: Benoy’s son, a child at the time of Amarendra’s death.

• Balika Bala: Stage actress, dancing girl, and Benoyendra’s principal mistress.

• Rabindranath Pandey: Amarendra’s uncle and defender, and a trained ayurvedic doctor.

• Kalidas Gupta: Diminutive lawyer turned sleuth for the Pandey family and the Calcutta police.

The Doctors

• B.P.B. Naidu: Head of plague research at the Haffkine Institute in Bombay. Part of a new generation of Indian scientists who rose to challenge European dominance of medical research on the subcontinent.

• P.T. Patel: Superintendent of the Arthur Road Infectious Disease Hospital.

• Nalini Ranjan Sen Gupta: Senior Calcutta physician.

• Santosh Gupta: Nalini Ranjan Sen Gupta’s nephew and a researcher at the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine.

• C.L. Pasricha: Professor of pathology at the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine.

• A.C. Ukil: Calcutta pulmonologist, and director of a laboratory at the All-India Institute of Science.

1

Every Inch an Aristocrat

November 1933: Howrah Station

For most of the year, Calcutta is a city of steam, a purgatory of sweaty shirt-backs, fogged spectacles, and dampened décolletage. A place for melting. In summer the cart horses pull their wagons bent low under the weight of the sun, nostrils brushing hooves, eyes without hope, like survivors of a high desert massacre. The streets are ‘the desolate earth of some volcanic valley’,1 where stevedores nap on pavements in the shade of merchant houses, deaf to the music of clinking ice and whirring fans behind the shuttered windows above.

The hot season gives way to monsoon and, for a while, Calcuttans take relief in the lightning-charged air, the moody daytime sky, and swaying trees that carpet the street with wet leaves, until the monotony of downpour and confinement drives them to misery. The cars of the rich lie stalled in the downpour, their bonnets enveloped in steam, while city trams scrape along the tracks. Then the heat returns, wetter this time, to torment again.

Each winter there comes an unexpected reprieve from the furious summer and the monsoon’s biblical flooding. For a few fleeting months, the brow remains dry for much of each day, the mind refreshingly clear. It is a season of enjoyment, of shopping for Kashmiri shawls and attending the races. Their memories of the recently passed Puja holidays still fresh, residents begin decking the avenues in red and gold in anticipation of Christmas. With the season’s cool nights and determined merriment, to breathe becomes, at last, a pleasure.

Winter is a gift, providing a forgiving interval in which, surrounded by goodwill and a merciful breeze, even the most determined man might pause to reconsider the murderous urges born of a more oppressive season.

Or so you would think.

On 26 November 1933, the mercury in the former capital of the British Raj peaked at a temperate 28°C, with just a spot of rain and seasonally low humidity. On Chowringhee Road, the colonial quarter’s posh main drag, managers at the white-columned Grand Hotel awaited the arrival of the Arab-American bandleader Herbert Flemming and his International Rhythm Aces for an extended engagement of exotic jazz numbers.2 Such was Flemming’s popularity that the Grand had provided his band with suites overlooking Calcutta’s majestic, lordly, central Maidan with its generous lawns and arcing pathways, as well as a platoon of servants including cooks, bearers, valets, a housekeeper, and a pair of taciturn Gurkha guardsmen armed with their signature curved kukri machetes. Calcuttans, Flemming later recalled, ‘were fond lovers of jazz music’.3 A mile south of the Grand, just off Park Street, John Abriani’s Six, featuring the dimple-chinned South African Al Bowlly, were midway through a two-year stand entertaining well-heeled and well-connected audiences at the stylish Saturday Club.

The city was full of diversions.

Despite the differences in culture and climate, if an Englishman were to look at the empire’s second city through just the right lens, he might sometimes be reminded of London. The glimmering of the Chowringhee streetlights ‘calls back to many the similar reflection from the Embankment to be witnessed in the Thames’, one chronicler wrote.4 Calcutta’s cinemas and restaurants were no less stuffed with patrons than those in London or New York, even if police had recently shuttered the nightly cabaret acts that were common in popular European eateries,5 and even if the Great Depression could now be felt lapping at India’s shores, leaving a worrisome slick of unemployment in its wake.6

With a million and a half people, a thriving port, and as the former seat of government for a nation stretching from the plains of Afghanistan to the Burma frontier, Calcutta was a thrumming engine of politics, culture, commerce – and crime. Detectives had just corralled a gang of looters for making off with a small fortune in gold idols and jewellery – worth £500,000 in today’s money – from a Hindu temple dedicated to the goddess Kali. In the unpaved, unlit countryside, families lived in fear of an ‘orgy’ of abductions in which young, disaffected wives were manipulated into deserting their husbands, carried away in the dead of night by boat or on horseback, and forced into lives of sexual bondage.7

Every day, it seemed, another boy or girl from a ‘good’ middle-class family was arrested with bomb-making materials, counterfeit rupees, or nationalist literature. Each month seemed to bring another assassination attempt targeting high officials of the Raj. The bloodshed, and growing public support for it, was disturbing proof that Britain had lost the Indian middle class – if it had ever had them.

Non-violence was far from a universal creed among Indians yearning to expel the English, but it had mass support thanks to the moral authority of Mohandas Gandhi. Gandhi, the ascetic spiritual leader whose campaigns of civil disobedience had galvanised tens of millions, was then touring central India, and trying to balance the social aspirations of India’s untouchables with the virulent opposition of orthodox Hindus – a tightrope that neither he nor his movement would ever manage to cross.

And from his palatial family seat at Allahabad, the decidedly non-ascetic Jawaharlal Nehru, the energetic general secretary of the Indian National Congress, issued a broadside condemning his country’s Hindu and Muslim hardliners as saboteurs to the cause of a free and secular India.8 Nehru had already spent more than 1,200 days behind bars for his pro-independence speeches and organising. Soon the son of one of India’s most prominent families would again return to the custody of His Majesty’s Government, this time in Calcutta, accused of sedition.

It was in this thriving metropolis, the booming heart of the world’s mightiest empire, that, shortly after two o’clock in the afternoon on that last Sunday in November, well below the radar of world events, a young, slim aristocrat threaded his way through a crowd of turbaned porters, frantic passengers, and sweating ticket collectors at Howrah, British India’s busiest railway station.

He had less than eight days to live.

Amarendra Chandra Pandey, just 21, couldn’t know that he was moments away from an incident that would lead to his own agonising death; or that his storied dynasty, one stretching back to the days of the Great Mughals, would in a matter of months be known to the world, broadcast across the globe in tones of horror and amazement, tragically associated with greed, lust, and the perversion of science. All Amarendra wanted was to get home to the comfort of his bungalow in Pakur, 174 miles away, a sprawling country district of black stone mines, forests, and paddy that his clan had ruled for generations.

It had been a trying year. One of Amarendra’s elder sisters, Kananbala, had died only months before of what was believed to be a sudden case of the mumps, leaving a husband and teenage daughter. Whatever one’s station, life was precarious in the pre-antibiotic era, and the Pandeys were shaken by the pitiless speed with which Kananbala had been lost.

Amar, who had been an avid tennis player and horseman, was himself still recovering from a vicious, bone-wracking bout of tetanus that had left him with lasting heart damage and a crippling secondary infection. Amarendra had spent weeks paralysed, mute with lockjaw, surviving on teaspoons of rice gruel. Still, most tetanus infections ended in death; his troubled recovery was regarded as something of a miracle.

But the young man’s troubles weren’t only medical in nature. There was a growing, unspoken concern among the close-knit clan that Amarendra’s physical challenges were congruent with financial ones. Amid a deluge of evidence that his bullying elder half-brother was looting their shared estate, Amarendra had recently overcome years of reluctance and was now preparing to divide their jointly held property, known as the Pakur Raj.

Benoyendra Chandra Pandey, the powerful Raja of Pakur, had warned Amarendra that he would ‘break bones’ over any effort to interfere with their shared patrimony. The threat wasn’t taken lightly. Benoy’s nickname was Sadhan, Bengali for fulfilment. One of his few admirers would later say that Benoy possessed ‘physical charm beyond any comparison – a tall physique, generous forehead, doe-eyes’, with shoulders like those of an ox and arms as long and thick as the branches of sal trees. Benoy, he recalled, was ‘every inch an aristocrat’.9

Others described a pampered, heavyset man with the latent aggression of a wild boar, a quick mind, and a natural air of even-tempered command. People did as he wished. ‘I never saw him angry,’ one of Benoy’s chief antagonists would later recall. Where slender and dutiful Amarendra was the perfect image of a young, unmarried member of the rural Bengali aristocracy, Benoy was iconoclastic, an open drinker, and a ladies’ man who, it seemed, never missed an opportunity to offend the sensibilities of his relatives. Since his father’s death from a bacterial infection four years earlier, the new Raja of Pakur had worked relentlessly to seize the properties of his kinsmen and expand the borders – and income – of his back-country fief.

Fratricide is the oldest crime, with many methods available to a brother with the requisite sociopathy. Benoyendra, 32, had that in spades, but he also possessed vision. A would-be impresario of the growing Indian film industry, Benoy hatched a conspiracy that would guarantee Amarendra’s death and his own financial freedom. Rather than having his younger brother hacked to death on some rural backroad by hired goons (a not-uncommon practice among the perpetually feuding gentry), shooting him dead in a hunting ‘accident’, or slowly poisoning Amar with, say, arsenic, as royals and commoners alike had done since at least the Middle Ages, Benoy, a twentieth-century predator loose among Victorians, set his eyes on a thoroughly modern murder.

Inspired by one of English literature’s most popular heroes, using medical science in the service of violence, the raja employed a weapon that, he was sure, would make the cause of Amarendra’s demise untraceable. The boy’s death would easily be chalked up to any one of the grand buffet of viral and bacterial fevers that regularly claimed the lives of Indians and Europeans of all classes in the humid, littoral metropolis.

Benoyendra hatched a plot to strike his brother with stealth, speed, and audacity. By joining forces with a down-and-out physician, and using a well-paid assassin with the nerve to do with his own hands what the doctor and the nobleman could not, Benoy would finally be rid of his troublesome sibling and free to dream and spend as he pleased.

Accompanying Amarendra on platform three that fateful day was his iron-willed aunt, surrogate mother, and would-be protector: the Rani Surjabati Devi. A wealthy dowager, and the widow of their father’s brother, Surjabati had raised Benoyendra, Amarendra, and their two sisters. As the boys grew, she struggled to shield Amar from Benoyendra’s neglect, and later from his veiled, mounting threats. Not content with looting Amarendra’s share of their patrimony, Benoy was also eying the ample properties that the woman he called ‘Mother’ had inherited from her late husband. The brothers were in line to inherit equal portions of Surjabati’s estate, which produced an annual income even bigger than their own.

Surjabati’s influence over the younger brother was a constant irritant. ‘It is his wish that I should not have any connection to you,’ Amarendra wrote to her in 1932. Privately, the aunt and elder nephew loathed one another. In public they performed with Arctic civility. Surjabati, despite her wealth and seniority, was disadvantaged in her long duel with Benoy. He was the karti, the undisputed leader of his wing of the family, while the rani was a childless widow, with no biological son of her own, in an era when widows were still expected to live out their days in joyless seclusion. The small, formidable woman in wire-rimmed eyeglasses, who had married into the family as a young teenager, was holding her own against Benoyendra in a contest as old as the aristocracy itself. No one understood he was playing by new rules.

At the East India Railways’ Howrah Station, Amarendra collected tickets for his homeward journey on the Pakur Express. Surjabati had already sent ahead instructions for her household servants to burn incense, to wash down the cots and chairs with pest-killing phenyl, to beat and air the cushions and bedding, and to tie fresh leaves to the entry gates in preparation for their arrival. Surjabati, Amar’s sister Banabala, and his teenage niece Anima Devi would accompany him on the northbound train. They were joined at the station by a handful of relatives and friends, including, to everyone’s surprise, an ebullient Benoyendra who, most uncharacteristically, had also come to see them off.

Amarendra, tickets in hand, led the party in a line towards their waiting train through a clamour of steam whistles, footfalls, and hawkers, his elder brother at the rear. A moment after crossing from the public booking hall to the station hall, with their platform in sight, Amarendra gave a shout.

‘I have been pricked!’

2

These Jealous Impulses

As the family gathered in the shadow of their carriage, Amarendra described a collision with a short, muscular stranger, ‘not a gentleman’, wearing traditional homespun cotton, who’d barrelled into his right side, ricocheted away, and vanished among the thrust of travellers.

Amarendra’s beige shirtsleeve was wet with an oily substance the colour of clarified butter; he rolled it up and the party gathered to stare at a damp spot on his upper right shoulder marked by a solitary pinprick. His niece, Anima Devi, stood on her toes and scanned the crowd in a futile search for the assailant. Rani Surjabati felt a chill and leaned on the piled baggage for support. She had experienced the deaths of her husband, her brother-in-law, sisters-in-law, and an adopted daughter. She stared at her young ward, full of foreboding.

As the women boarded the train, Amarendra’s cousin, Kamala Prosad Pandey, insisted he remain in Calcutta and have his blood tested, and for a moment Amarendra appeared to waver. Then his dada, his elder brother, pushed through the crowd, seized the affected arm and, peering at the strange wound, rubbed the oily red dot with his bare thumb and laughed. Benoyendra accused them of ‘making a mountain out of a molehill’. He bore down on Amarendra ‘and, in a way,’ Kamala recalled, ‘forced him into the compartment.’

‘That is nothing,’ Benoyendra said, manoeuvring Amar to his seat. ‘Go home.’ The cousin protested, but Benoy cut him off: Amarendra had but one elder brother, and even as an adult he was duty-bound to obey. Everyone knew this, lived this. Kamala backed off. Even in extraordinary conditions, the old ways prevailed. With characteristic obedience, Amarendra stayed on the train, ceremonially touching his brother’s feet before Benoy departed.

It was his final capitulation. There the boy sat, miserable. Surjabati lay stretched out on the bench opposite. His sister Banabala produced a bottle of iodine and daubed at the wound. Amarendra asked for a knife to cut away the affected flesh, but no one was carrying a blade. They rattled on.

As the locomotive bore north to the comforts of home, Amarendra’s body was already in the opening engagements of a losing battle with a killer that had once consumed half of Europe and that had been scything its way across India for more than two decades. The virulent germs the strange assailant had driven into his arm began to multiply, releasing endotoxins that would in the coming days cause at first scores, and then hundreds of tiny blood clots to form silently throughout Amarendra’s body. Their blood supply being choked off by these clots, Amar’s organs faced a slow death. With his body’s coagulants depleted, and colonies of pathogens growing exponentially, blood from Amarendra’s damaged tissue would soon begin seeping into his lungs.

Back home in Pakur, an uncle chastised Amar for having ever left Calcutta, with its world-class doctors, and begged him to return before he became ill with whatever had been stabbed into him.

With a resignation that can be heard, mournful as a bell, from that century to this, Amarendra replied: ‘My brother is determined to take my life. What precaution can I take?’

***

The Pandeys were wealthy zamindars: local gentry who had ruled over a poor area of subsidence rice farmers, black stone mines, and timber-rich forests since the days of the sixteenth-century Mughal emperor Akbar the Great. Over the course of more than 400 years, the clan had wrung every anna it could from the largely illiterate population of a realm bigger than modern New York City. In 1929, the Raja of Pakur, Protapendra Chandra Pandey, died and left the estate to his two sons, the half-brothers Benoyendra, 27, and Amarendra, 16. From a promontory on the third-floor verandah of the tallest building for miles, Benoyendra and Amarendra could gaze in any direction, over paddy, woodland and hamlet, satisfied that, by law, custom, and divine right, nearly all they surveyed was theirs.

Behind the walls of their whitewashed ancestral palace – a castle-like bastion built to withstand an indigenous peasant uprising – Rani Surjabati Devi raised them as her own. Despite an outward appearance of solidarity, the brothers’ relationship was defined by rivalry and resentment, and by Benoyendra’s need to assert himself as their father’s one true heir. Benoy would battle first for maternal love, and later for money and power.

As the son of a zamindar, Benoyendra had enjoyed a luxurious childhood, raised in a palace, attended by servants, with nannies and tutors to keep him company and assure his proper upbringing. His education would include lessons in English, Bengali, horsemanship, and shooting. Benoy’s mother had died when he was just 3 years old, and Surjabati moved into the Gokulpur Palace to care for him and his younger sister Kananbala, serving as a rock of love and continuity. She stayed on after their father remarried and, when the raja’s second wife died after childbirth, she took on Benoyendra’s half-sister Banabala and the newborn Amarendra, who would never know his birth mother. As the boys grew to adulthood, Surjabati remained a pivotal figure in the household – they called her ‘Mom’ and ‘Mama’.

It would have been natural for Benoyendra to feel some small resentment of the new baby. In a culture where sons were prized well above daughters, Amarendra’s arrival represented a dilution of Benoy’s supremacy, despite his unassailable position as the eldest male. But when Amarendra’s mother died of complications from childbirth, Benoyendra suffered a more severe blow, as Surjabati swept in to care for the motherless newborn and his toddler sister. The tiny boy was hers from almost his first moment; in an instant, Surjabati’s love for Amarendra eclipsed her motherly bond with Benoy. He never forgot it.

Twice robbed of maternal affection, Benoyendra responded to this emotional dethronement with a lifelong resentment of his aunt and the pretender Amarendra. He would evolve into a grandiose figure, rebelling against the careful and rigorous social mores of his community, using money as a weapon against his closest family, and finally turning to violence to excise this narcissistic injury. Sigmund Freud was referring to relations between sisters when he wrote, ‘We rarely form a correct idea of the strength of these jealous impulses, of the tenacity with which they persist and of the magnitude of their influence on later development,’1 but he could just as well have been observing Benoyendra’s festering animus for his younger brother. Despite his father’s favour and his primacy as the future raja, Benoyendra saw himself as the odd boy out, and now saddled with a co-heir whose well-being he would one day be responsible for.

Compared with most Indians of that era, the Pandeys were unimaginably wealthy. Even by international standards they were rich, with an estate producing income worth a princely £20,000 a year at a time when English farm workers were taking home a little more than a pound a week,2 and most Indian incomes amounted to mere pocket lint in London and New York. The family’s privilege was tethered to the land, and to the time-bound mores of the rural nobility. Long before the forces of Robert Clive defeated Siraj-ud-Daulah at Plassey, before Job Charnok set up the malarial Ganges River post that would become Calcutta (now Kolkata), the forested hills and fertile valleys surrounding Pakur, 174 miles upstream in a region known as the Santhal Parganas, had already been under the rule of ‘outsiders’ for centuries.

The Pakur Raj dynasty descended from north Indian imperialists, a clan of Kanyakubja Brahmins born on the plains near Lucknow who arrived in the late 1500s to tame the rough lands and peoples found near the eastern margins of the Mughal Empire. They would rule over the region’s tillers and indigenous hill people in the name of Akbar the Great.

Their leader was one Sulakshan Tewary, who had seen his ancestral properties in the north turn lifeless from an ‘all-pervading pestilence’.3 Rich, unclaimed lands, however, were available in the east for a freebooter brave or desperate enough to pull up stakes. Tewary secured a land grant, or jagir, from the emperor for a wild, unconquered place neither had ever seen. As a zamindar, with the powers of a small monarch, Tewari would fold this virgin territory into the Mughal embrace and convert its thousands of peasants into Akbar’s loyal, rent-paying subjects.

Tewary and his followers made a rutted journey halfway across the subcontinent to fulfil this manifest destiny. The train of newcomers made a slow advance through dense jungle dotted with villages and hamlets, until finally it reached a stretch where India’s vast, green flatlands gave way to hill country and the great Ganges delta, a place of swaying sal trees, Bengal tigers, and small farms raising rice and pulses. This was now home.

Akbar’s writ notwithstanding, the local farmers and strongmen, led by a skilled archer named Satyajit Roy, chose to resist the Persian and Awadhi-speaking invaders. The sons of the soil drew first blood but ‘were soon pacified and agreed to pay rents out of which the due amount of imperial tribute was remitted to Delhi’.4 A new dynasty was born. Tewary restored his finances off the backs of his new subjects, while they adjusted to the novelty of having an emperor to support. The new zamindar’s grandson later helped Mughal forces defeat the rebellious ruler of Jessore, and the Tewary clan were rewarded with gifts from the emperor, including the hereditary title of ‘raja’.5

Four centuries later, Tewary’s descendants, by now absorbed through marriage into the rural Bengali aristocracy, continued to rule over Pakur, with many of the same powers and responsibilities as their founding figure. Tenant farmers worked the land, and paid rent to Benoyendra and his clan. After taking their generous cut, the Pandeys funnelled a portion of the proceeds to the imperial government in the form of taxes. They had fulfilled this role first under the Mughals, then for the Nawabs of Murshidabad, and finally under the British. Some version of this arrangement obtained on nearly every square inch of rural land across Hindustan.

If poor farmers and other tenants formed the base of this pyramid, the upper layers were taken up by the extracting class, the retinue of hired assessors and collectors paid to manage the estates and squeeze money from the residents, followed by the bookkeepers and pleaders who managed a landlord’s accounts and his many legal disputes. An estate like the Pakur Raj had diverse income streams, ranging from the rent roll, the zamindar’s own crops from land he personally controlled, to the stranglehold loans he made to tenants and local businessmen. A zamindar had to mind his retainers for signs of corruption – they might be taking bribes to accept smaller payments, or they could be creaming off the rent roll. In October 1932, Benoyendra was irritated to learn that Rani Surjabati had hired an employee he had recently dismissed.

‘To Your Lotus Feet,’ he addressed the woman who raised him, before getting to the point:

Boma [Mother], are you doing well in keeping the man whom I was compelled to dismiss on account of him taking bribe[s] and spoiling our work again and again [?] … You should have at least asked me a word about it … You can, of course, show me disrespect a thousand times, but I hope I shall be able to show you soon whether I can also do so to you once. Do what you think proper. Finis.

She cut the man loose.

Pakur was a money machine, but there was little room for growth. A zamindar could increase his wealth with a strong harvest, by acquiring new land through purchase or litigation, or through efficient management. While Benoy had a zeal for lawsuits, including against members of his own clan, he was considered a disaster as a manager. A friend whose name is now lost to the public record warned him in a letter that without reform, ‘You will find within a year or two that you are involved in debts and your property is put up for sale.’

A zamindar’s obligations to the Crown were fixed – he was expected to pay up through boomtime, famine, and drought. Those who failed found their properties auctioned off by the government, their income and honour diminished. Two of Benoy’s ancestors met worse fates: one was imprisoned by the torture-happy Nawab of Murshidabad in the mid-1700s and forced to abdicate in favour of his brutal father-in-law after failing to extract sufficient tribute from his war-weary tenants. After a famine in 1770 killed one-third of the peasants in lower Bengal, another of Benoy’s predecessors was also imprisoned for his arrears, but he somehow managed to gain freedom, keep the throne, and pass it to his son.

‘Be on friendly terms with your tenants,’ Benoyendra’s friend added, ‘otherwise they will revolt.’ Instead, the new raja kept retainers who were notorious for their greed and cruelty. His trusted estate manager, or dewan, the friend warned, ‘commits violent oppressions on the tenants, and if a criminal case is started in consequence then it is your money that will be spent [fighting it]’.

Benoyendra should have been especially sensitive to the risks posed by treading on his feudal subjects. Nearly eighty years earlier, one of his predecessors, the wealthy Rani Kshemasundari, narrowly escaped having her throat cut during the Santhal Rebellion of 1855–56, when the region’s indigenous tribal people exploded in violence against their overlords. (A despised moneylender wasn’t so lucky: a band of Santhals captured and dismembered him alive, joint by joint, after he tried to take control of Pakur in her absence.)6

The trusted manager was ‘slowly swallowing you just like a snake swallowing a frog, and he is stealing’, the friend wrote. The manager, together with a stalwart lawyer from Benoy’s court, he added, ‘have misappropriated large sums of money belonging to you’. But such was their hold over Benoyendra, he complained, that the raja couldn’t recognise the fraud, ‘and you have no power to. It is difficult to know these men in their true colours.’

Mistrust was like mother’s milk for the gentry, and a zamindar had to believe in somebody. Often it was the cronies of his youth. Forty years earlier, the Bengali writer Lalit Mohan Roy had bemoaned the moral decline of the zamindar class, describing how, in boyhood, a young scion’s servants and friends would ‘indulge their minor lord into all sorts of wicked pleasures and pastimes with every mischievous device that can minister to his boyish fancies, often purposely impurified – and thus the first seeds of corruption are sown in him’. In an atmosphere of constant competition, other landowners were usually seen as rivals or potential adversaries. ‘Among his fellow zamindars he can expect none as a friend.’7

As for Benoyendra’s young wife, Srimati Pritilata Devi, their marriage existed in a state of partial estrangement. Married in her early teens, Benoy’s wife lived in purdah, all but confined to the home, with little influence over the family’s affairs.

As was the custom, Benoy lived in separate rooms, and dined alone or with male friends. Only occasionally did his wife leave the palace’s zenana, or women’s quarter, to visit him in his chambers. It was considered indecorous for a respectable husband to take daily pleasure in his wife’s company and, anyway, there were ample amusements among the household maidservants, to say nothing of the treats available in Calcutta. This domestic formality applied to a zamindar’s children as well – the father would see them at pre-arranged times, with no random capering at his feet during the day.

In a dignified photo portrait of the married couple, a moustached Benoyendra is seated on a carved wooden stool, a small slouch to his thick-boned frame, wearing a silk pyjama kurta and sandals, facing to the right. The petite Pritilata stands behind him, her right hand on his shoulder, dressed in a sari she’s wrapped around the back and over her shoulder and head, a jewelled belt at the waist. She faces the camera without expression, a hint of confidence in her gaze.

***

In a less noxious setting, Amarendra too would have married a girl from a Brahmin clan selected in consultation with his surrogate mother. Living as part of a joint family at the Gokulpur Palace with Benoyendra’s wife and three children, Amar would remain closely involved in the estate’s affairs, watching the harvests and the rents, advising Benoyendra where his contributions were welcome. His years would be shaped by the rural seasons and the calendar of rituals and festivals, with winter getaways to the theatre and the cinema in Calcutta. But he never got the chance.

The morning after reaching home, Amarendra felt well enough, the events on the platform receding into a kind of bad dream. The following day proceeded without discomfort. The family told almost no one of the incident at Howrah, not even their trusted local doctor. Still, Amar made arrangements to visit Calcutta on Wednesday, 29 November, for a precautionary check-up. There, he was examined by Nalini Ranjan Sen Gupta, a respected doctor who had published both clinical research on tuberculosis and medical commentary defending India’s traditional Ayurvedic medicine against the sneers of Western scientists.

When Amarendra, still in outwardly fine health, asked if he could hop on a train back to Pakur that evening, Sen Gupta advised him to stay in town another night. It was prescient advice. Amar awoke the next day with a fever and an ache in his right arm; Sen Gupta ordered a blood sample for culture at the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine.

It was now clear that the pinprick had caused some kind of infection, but what? An analysis of his blood would lead Amarendra’s growing medical team to a diagnosis, but it would take time to culture and identify the pathogen. An uncle telegraphed Surjabati that Amar was quite ill, and she, his sister, and his niece Anima made a beeline for the city. By 1 December, the site of the pinprick had developed into a slightly raised weal, and a lump was forming under his arm. Amarendra’s fever worsened the next day, and by Sunday, the 3rd, he was placed on oxygen.

There, in the front room of Surjabati’s home on Jatin Das Road (named for a jailed freedom fighter who died after a sixty-three-day hunger strike), Amar’s breathing became laboured. Her young uncle was still speaking, Anima recalled, until sometime around 10 p.m., when Amar went silent, his energies concentrated in a vain effort to breathe. Amarendra died before dawn on Monday, 4 December 1933, at age 21. Benoy, who had been so eager to see his younger brother off from the train station just eight days before, was staying in a rented house just a mile away. Not once had he come to visit.

3

The Nervous Bhaiya

Shortly after word of Amarendra’s death reached Pakur, Benoy received a jaundiced letter of congratulation from his scolding, judgemental friend. Addressing Benoyendra by his nickname, the correspondent wrote: ‘Sadhan …, you are now in luck. All these days you thought that you had a co-sharer, and with this idea you attached no value to properties and squandered away money according to your sweet will. Now you have no further cause for anxiety.

‘Then why are you still indifferent to your family affairs?’

Benoyendra’s chum was labouring under a misapprehension. Benoy, he imagined, had been burning money not because it was fun – the only way to live, really – but because half the cash he spent was Amarendra’s, and it was a joy to spite him. Now, the friend said, there was nothing to keep Benoy from a prodigal’s return to the straight and narrow. With Amar out of the way, Benoyendra could finally, at last, be good. Benoy, a hedonist to the core, was deaf to this logic. ‘Even now,’ the friend complained, ‘you do not hesitate to squander away money.’ With Amar dead, he said acidly, ‘Just think how much you have got to spend now for the two mistresses that you have kept.’

A lawyer close to the Pandey family would later observe that he was running his estate into the ground. ‘The staff employed by Benoyendra are incompetent,’ he would say in official testimony. ‘Money is being spent but the accounts are not written up … He comes frequently to Calcutta … He spends it on prostitutes.’ Benoy’s expenses included a car and driver, a suite at the Calcutta Hotel, a rented house in the city, and lots of whiskey. But these were dwarfed by the small fortune he spent on women.

The raja’s local standby was a courtesan named Chanchala, who he kept at a bungalow in Pakur town. What he apparently didn’t know or perhaps avoided knowing, his friend claimed, was that Chanchala played with other men on the side. ‘Does she depend only on you?’ he asked with a touch of spite. ‘If you think so, then you are quite mistaken.’ Rather, Chanchala had been making a fool of her benefactor, two-timing him with a steady clientele of low-rent functionaries.

‘Jogen is her dalal,’ or go-between, he wrote. ‘He brings every day big Bhakats1 of Harindanga,2 Babus of the station, Sub-Registrars, Deputy Magistrates, and Police Babus who she entertains. One or two of these men are brought every day.’ Chanchala spent the proceeds of these liaisons on parties for her friends, while salting the balance away in a postal savings account. (The fact that Chanchala controlled her own bank account added scandalous insult to injury; it was unseemly, his friend intimated, that a woman should have money of her own.)

‘But not realising this you are still in love with her,’ he admonished Benoy. ‘Do you not feel a sense of loathing in the least?’

The answer was no. Benoy’s loathing was reserved for stiffs who followed the rules and the harpies who enforced them. And while it is possible he was unaware of Chanchala’s parallel life and the betrayal that would represent, another likely explanation was that Benoyendra had something to gain from her freelance encounters. The daily parade of second- and third-tier bureaucrats Chanchala serviced were the nervous system of the Pakur administration – the men who ran its records office, courts, police, and telegraph. A wise king, wrote Kautilya, mentor to the great Iron Age emperor Chandragupta Maurya, ‘keeps his eyes open with spies’.3 Like a canny intelligence officer, Benoy had built a network of sexually gratified insiders who were happy to lend a hand in his local conspiracies. Chanchala was more useful to him as an ex-mistress than as a loyal companion.

Besides, he always had Balika.

In Calcutta, Benoyendra maintained a durable romance with a stage actress from the Natya Mandir theatre known as Balika Bala. Balika had appeared in the hit Bengali satirical play Khas Dakhal – ‘The Land One Possesses’ – at the Star Theatre, remembered by critics for the laugh line, ‘What, my temperature is 99?’ The satirical play ‘puts a sling on the so-called advanced people of South Calcutta’, one critic recalled.4