8,22 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Proisle Publishing Services

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

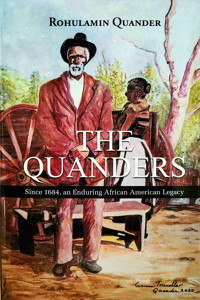

The selected title of this book, The Quanders - Since 1684: An Enduring African American Legacy, is self-explanatory and becomes more so once the reader delves into the content. Tracing the legacy of Henry Quando and Margrett Pugg, his wife, and their progeny, from 1684 to the present, unfolds a story of triumph and sustained accomplishment beyond and in spite of whatever racially-inspired obstacles were placed as inhibitors on the road to success.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 368

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

The

Quanders

Since 1684, an Enduring African American Legacy

Rohulamin Quander

The contents of this work, including, but not limited to, the accuracy of events, people, and places depicted; opinions expressed; permission to used previously published materials included; and any advice given or actions advocated are solely the responsibility of the author, who assumes all liability for said work and indemnifies the publisher against any claims stemming from publication of the work.

All Rights Reserved

Copyright © 2022 by Rohulamin Quander

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher disclaims any responsibility for them.

Proisle Publishing Services LLC

1177 6th Ave 5th Floor

New York, NY 10036, USA

Phone: (+1 347-922-3779)

ISBN: 979-8-9868665-9-8 Paperback

ISBN: 978-1-959449-52-2 Hardback

ISBN: 978-1-959449-53-9 Ebook

TABLE OF CONTENTS

In Praise of The Quander Story……………………………………...4

Acknowledgments……………………………………………………6

Dedication..…………………..............................................................7

Introduction…………………..............................................................8

Chapter 1 The Early Years: Henry Quando and Margrett Pugg14

Chapter 2 Bastards or Babies?28

Chapter 3 The Entrepreneurial Spirit lives35

Chapter 4 The Quander Family Seems to Disappear42

Chapter 5 Quanders, Clagetts, and a Walnut Tree56

Chapter 6 Felix Quander: Negro Thief or Honorable Man?67

Chapter 7 Quander Street: A Qashington, DC, Historic Site84

Chapter 8 The Quander Family Reunion and Quanders United94

Chapter 9 The Tricentennial Celebration, 1684-1984116

Chapter 10 The Quanders begin their fourth century141

Chapter 11 The Mount Vernon Slave Memorial166

Chapter 12 Coming Full Circle: A Trip to Ghana191

Epilogue………................................................................................215

Appendix: Quander Achievements and Actions of Notes

Faith Communities………..219

Professional and Personal Achievements…235

Military Service and Leadership265

About the Author…………………………………………………….....275

Notes…………………………………………………………………......277

IN PRAISE OF THE QUANDER STORY

Few families, other than Native Americans, can show detailed evidence of an American heritage that spans well over three centuries. Even fewer can identify foreparents whose lives intersect with George Washington, the first President of the United States and Francis Scott key, the lawyer who penned the inspiring verses of the National Anthem. In Rohulamin Quander’s remarkable narrative— made even more remarkable by being an African American story — such historical evidence appears as early as the 1760s in the Catholic-founded colony of Maryland. Acquiring freedom from slavery by their master’s will in 1684, Henry and Margrett Quando began the record of the Quander family’s long journey and repetition of names, sustained religious faith, and commitments to equal justice and personal achievement throughout the many generations. The book’s exhaustive documentation and compilation of court cases, state archives, probate records such as the will of George Washington, census data, street names, newspaper articles, and historic sites bring the life the Quander men and women and their experiences in Maryland, Virginia, and Washington D.C. from the seventeenth to the twenty-first century. The QuanderStory thus represents many stories of kinship that chronicle the tie that binds and sometimes fray, but ultimately unite in a shared memory, recurrent family reunions, and ethe eventual discovery of the family’s African ancestral roots int eh Amaquandoh family of Accra, Ghana.

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham

Victor S. Thomas Professor of

History and of

African and African American Studies, Harvard University

National President, The Association for the Study Of African American Life and History

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My dear wife, Carmen, who always believes in, and encourages me to go forward and aim higher. She is my shining star.

To my adult children – Iliana, Rohulamin, II, and Fatima;

They always make me look good in all that I do.

To James W. Quander and Joheora Rohualamin Quander, my loving parents, always dedicated and focused upon instilling Christian values and a moral standing into me and my siblings.

All Amkwandoh (Amaquandoh) ancestors in Ghana, who in their suffering and sustained indignity, created the foundation upon which this story, an American History story is built.

All of my Quando/Quander ancestors, who were involuntarily brought to this land, then enslaved only in body, but never in their minds. I give you my highest praise.

All of my Quander ancestors, whether born free or enslaved as of January 1, 1863, I thank you. Your presence and contributors made this history. Without you, there would be no story to share and tell.

Gladys Quander Tancil, Story Teller, Sustainer, overlay of this product, always with some new information, and likewise encouraging me to move forward and share The Quander Story.

And Elaine Eldridge, my Editor, my wordsmith. She guided me in telling the story, without loosing any of the essence of the history. She really helped me to Make It Happen.

DEDICATION

I dedicate The Quander Story and all that it represents In Memorium to George Floyd (May 25, 2020) a Soul Brother who died too soon at the hands of the sustained racism and indignities that, since 1619, continue to daily characterize African American lives. Indeed, WE CAN’T BREATHE! George never intended to be a hero. Nor did he ever plan to be a martyr. But his life, and the manner and circumstances of his untimely death underscore to all of us how fleetingly insignificant a Black life in the United States can be. In dying - a lynching if you will - he unleashed the hurt, both physically and psychologically that has been pent up in the African American community for 401 years. The outpouring of recent events, generously embraced by our Caucasian brothers and sisters, have indeed underscored that Black Lives Do Matter.

I dedicate The Quander Story to John Edward (1883-1950) and Maude Pearson Quander (1880-1962), my loving grandparents. Their love of family and determination to save my father, James W. Quander’s life, as a child diabetic, is without equal. Through them, and my dad, The Quander Story lives and has been preserved. Thank you.

INTRODUCTION

As you turn these pages, place yourself into the atmosphere in which the African American–focused stories or occasions unfold. See yourself in the struggle facing and overcoming obstacles, many of which were racially motivated. As you progress from decade to decade and century to century, also grasp the sense of place, the disappointments, but still the triumphs of the people whose stories are told here. The refusal to be beaten! Only then can you fully appreciate how some of the ancestors’ achievements, while seeming insignificant by application of twenty first–century standards, were milestones at the time. From personal enslavement to freedom in a single life, or perhaps only one generation beyond, there was an unquenchable thirst to achieve. Whether by formal education, operating a business, or acquiring land to farm, these men and women were determined to do better, to do more, and to prove themselves to themselves.

What you are about to read, The Quander Story, is but one example of American history. Whether it be African American, European American, or otherwise, it is, more than anything else, an American story. Regretfully, our nation continues to experience racial attitudes and divisions that drive us apart and reject our shared stories. The murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, unsheathed a two-edged sword. One sharp edge—“I can’t breathe!”—underscores the continuing frustration, suffering, hurt, and anger African Americans have sustained since 1619, when the first enslaved and chained ancestors were involuntarily transported from Africa to Virginia. Yet the other sharp edge has cut an opening through which much long-standing apathy has been exposed, cutting away the lack of awareness, concern, and understanding of what African Americans (the other side) have endured for centuries.

America is changing, as people of all races, and especially a large contingent of American whites, have stepped forward, joined arms with their black, brown, and yellow brothers and sisters, and cried “Enough already!”

Is this the beginning of a New America? I certainly hope so. And the new America cannot come a moment too soon! African Americans built this country, despite the initial denial of the appellation “American” as a component of our identity. Our uncompensated labor from sunrise to sunset built the U.S. Capitol, the White House, George Washington’s Mount Vernon, other presidential plantation estate mansions, and the Smithsonian Castle, and even initiated the pre–Civil War construction of the Washington Monument. The enslaved constructed the streets in Washington, DC, upon which the enslavers rode in their well-appointed carriages, to sites where they enjoyed the various attractions and accumulated riches. What thought was given to the enslaved Africans who labored to create these comforts? Little to none! This book, although it cannot tell all their stories or make up for that lack of thought, is my contribution to telling the story of American history.

On August 11, 1968, I attended my first Quander Family Reunion. The times were turbulent. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy had been assassinated earlier that year, and the nation was still in a great uproar. Prior to the reunion, as I prepared to enter my last year as a student at the Howard University School of Law and assume the presidency of the Student Bar Association, I had little thought of where I had come from or what “To Be a Quander” meant.1 But the reunion piqued my interest in my history and reminded me that for years, as I served as an International Pal, interacting with foreign students, I was routinely called, “Mr. Quando” by some of the students from West African nations. Initially it meant nothing, perhaps just a mispronunciation of my surname. But the seeming error occurred too often. It made me think. One day I asked one of the students, who happened to be a Ghanaian, “What’s this about? Why do all these students call me ‘Mr. Quando’?”

“You mean you don’t know?” he asked in return. “Your name is Fanti, one of our Ghanaian ethnic groups. In Ghana the name is ‘Amkwandoh,’ and anywhere you go in Ghana and tell someone ‘I am Quando,’ they will immediately hear ‘Amkwandoh,’ and recognize it for what it is—a Fanti name.”

Curious about his insistence about our surname, I asked older family members if they had ever heard the name “Quando.” One very senior cousin said he heard from even older relatives that our name used to be spelled differently. “Back there somewhere,” he told me, pointing over his shoulder, “they said the U.S. census taker made a spelling error, and dropped the o and added er.” But no one knew exactly when “back there somewhere” was. Researching seventeenth- and eighteenth-century records verified the Quando name, and showed that the “back there somewhere” error did indeed occur in the U.S. Census of 1800. My later research reflects that both spellings, Quando and Quander, existed into the nineteenth century, finally resting with the “er” spelling.

Armed with this tidbit of information, you are ready to begin what is now widely appreciated as The Quander Story. Reading this book, you are embarking upon a more than 350-year journey, a legacy that stretches from the depths of abduction and enslavement to the heights of national acclaim. What did it mean to be an American who was enslaved by George Washington? How do their descendants feel about that situation? How are the Quanders different, but likewise similar, to other African American families? Inherent in this history are the lows of racial discrimination and mistreatment and the many and continuing successes that Quanders have enjoyed through the centuries. Perhaps this poem, by Lewis Lear Quander, captures from whence we came:

MIRACLE OF FAITH

(Tribute to my Mount Vernon Ancestors)

Imagine sir if you could be

Back in 1793,

Remembering the things that you crave

But cannot hope for - you’re a slave.

Freedom was a dirty word;

Only something that you’d heard.

It certainly don’t apply to you

And there’s nothing you can do.

Just pick that cotton, hoe that corn,

Wish that you were never born.

Your culture has been lost for years

And there you stand reduced to tears.

To be so helpless, yet so strong,

You knew there must be something wrong.

There’s nothing you can do or say,

Except look to the Lord and pray.

These unknown souls who lie with you,

What kind of labor did they do?

I know that some were kitchen hands;

Some worked with wood and some with cans;

Some dug ditches; some fixed fences,

Down where the dismal swamp commences.

With straw and mud they put together

Bricks that have withstood the weather,

And houses they built from the ground

Through all these years are still around.

Oh I’m as proud as I can be.

I know they did it all for me.

I know that I’m a better man

As on their shoulders here I stand.

I know that all the grief and pain

They bore could not have been in vain.

They lived in Faith and died in Hope

That somewhere, sometime they could cope

And find a way to make a stand

Against man’s inhumanity to man.

Alas, alas, ’t would not be so.

The grass upon their graves did grow.2

This book, which was more than 50 years in the making, was initially conceived as a family history.3 However, as more people, both nationally and internationally, became aware of the Quanders’ history, I was urged to tell the expanded story, one truly reflective of American history. This book is not another Roots, a fictional account based upon a slim set of facts. Instead, The Quander Story narrates a series of actual events that shows where we came from and who we are today. Some of the stories do not chronologically follow from what has immediately preceded. The national scope of the family history and the breadth of the family’s involvement dictate that several stories are freestanding and not directly related to what has gone before or what immediately follows. As you read, the story will morph from Negro and Colored, to Black and African American, to reflect racial identification during the changing time periods.

Some readers might perceive this book as a memoir. That is not my intent, although I must take a bow or two and give myself some credit for the many years I devoted to this effort, plugging away among old dusty records in the Maryland Hall of Records in Annapolis and the Fairfax County Courthouse Archives in Virginia. One of my good friends, an Omega Psi Phi fraternity brother, said that life was too short to spend time looking back. Smart as he was, a Howard University Phi Beta Kappa, his shortsightedness has actually been an inspiration to me, setting a tone for a wider appreciation of history and how it can help or hinder us. What is history, anyway? I believe history is to know, appreciate, and explain what has already occurred and to evaluate the present in the context of the past. That is exactly what The Quander Story seeks to do. Now it is your turn to read, enjoy, learn, savor, and share the tribulations, the triumphs, the failures and successes, and the unfolding story that is the legacy of the Quander family. Adelante!!!

CHAPTER 1

The Early Years:

Henry Quando and Margrett Pugg

In 1634 the Ark and the Dove landed in St. Mary’s City, bringing the first white settlers to what is now Maryland. Many came in pursuit of freedom to practice their Roman Catholic faith. The new colony was founded with a 1632 land grant awarded by King Charles I of England to Cecilius Calvert, the First Lord Baltimore, and was named “Maryland” for the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots and Mary the Mother of Jesus. Although Maryland was initially intended to be a colony open to religious tolerance, those hopes were soon dashed when the growing non-Catholic majority severely restricted the right of Catholics to practice their religion.

Among those early immigrants was Henry Adams, who traveled from England to the Maryland Colonyin 1639 when he was approximately 22 years old.1 Adams was indentured for several years to Thomas Greene in St. Mary’s County. Impoverished British emigrants could receive free passage to the New World by indenturing themselves, that is, contracting themselves to servitude, often for as long as seven years. After working off his period of indenture, Adams migrated north, and by 1650 had settled in Port Tobacco, Charles County, then the seat of the local legislature and government. As a literate, landed planter, Adams served in the legislature and Charles County government between 1661 and 1685. He also served as a justice and a sheriff during much of this time.2 His last will and testament, written on October 12, 1684, stated he was a widower without children and a Roman Catholic. At the time of his death he owned 800 acres in Charles County.

Will of Henry Addams

1684 Last Will and Testament of Henry Ad(d)ams, which freed Henry Quando and Margrett Pugg in 1686

Adams’s will freed two of his four enslaved, Henry Quando and Margrett Pugg. From the earliest days of colonial America, there were always a small number of free blacks, as slavery had not yet emerged as the heinous, widespread institution it later became. Some, like Henry and Margrett, obtained their general manumission upon the death of their owners, although the number of blacks achieving their freedom in this way was small compared with those who remained enslaved. The will suggests Adams had a personal relationship with Henry and Margrett. What else could his incentive have been to give the boy his own name and then to free both of them, while not bestowing the same benefit on the other two slaves? Although Margrett and Henry were considerably younger than Adams, they seem to have influenced him to the extent that he not only elected to free them, but provided them with items of personal property with which they could undertake independent lives.

Henry Adams may have given the boy his own English name out of affection, but his renaming also reflected the common practice of replacing the kidnapped victims’ alien African names with names the English and Irish settlers could easily relate to and pronounce. Renaming was part of the effort to subdue the slaves, to mold them as quickly as possible into subservient, docile beings who would soon have little or no recollection of their African pasts. In retrospect, however, Adams’s renaming his male slave was not all bad, as the consistent use of the name “Henry,” tied to the name “Quando,” created a road map in documenting the Quander family’s history. Occasionally we don’t know where to draw the genealogical line between one Henry and the next when there is a series of individuals, but that difficulty pales by comparison with the stability conferred by the repeated use of the name.

With the filing of Adams’s will for probate on July 4, 1686,the surname “Quando” became a public record in the Americas, thus documenting for the first time the presence of the Quando/Quander family in the colony of Maryland. The Quanders are accredited as the oldest, consistently documented African American family in Maryland, and possibly in all of the original thirteen colonies. Many of the secrets related to the introduction of the name in this hemisphere remained hidden for centuries, only to be rediscovered in the late twentieth century, when the descendants of the present generation of Quando family members in the United States met with the descendants of the shared ancestral root, the Amaquandoh family, in Ghana in 1991.

Adams’s will stated that Henry and Margrett were to be free to all intent, and purposes, as though they were noe negroes, alsoe I give [unto] the said Henry Quando one flock bed and what shall belong to it, also one small chest with a dutch lock of what shall be therein, also unto the said Margrett Pugg, one cow or calfe.3

They were “free,” the result of a benevolent act and good intention, but released into a hostile community where blacks were viewed as inherently inferior and presumed unable to carry out any tasks of significance. Henry and Margrett were illiterate, trapped in a strange land with a new and uncertain status, a probable loss of communication in their indigenous African languages, and no means of returning to their homeland. It is not even certain whether they were born in Maryland, Africa, or perhaps Barbados. In reality they may not have had any other land to call home, and they elected to stay in Port Tobacco.

During the early colonial period there was no direct slave trade between West Africa and the colonies. Rather, North American slave traders traveled to the West Indies, primarily Barbados or Jamaica, visited the slave markets, made their selections, and then put their newly acquired enslaved on ships headed north. For more than two centuries, there has passed from generation to generation of the Quander family the story of two brothers who were brought to Maryland from “the Islands” and then separated, never to be reunited. Remarkably, this story has persisted in both the Maryland and Virginia branches of the family even though, with the passage of time and the expansion of distances, the later generations of the extended Quander family did not know each other.

The story suggests that in Maryland the brothers were sold to different slave owners, presumably resulting in Henry Quando going to Henry Adams and his brother passing into oblivion. “Benjamin” is the only name I have ever heard for the lost brother. The “two brothers” story relates that the children of the freed brother (Henry Quando) and the children of the still enslaved Benjamin were able to reestablish contact in Maryland and vowed never again to lose sight of their familial relationship. They clung to that relationship tenaciously through the centuries, as would be apparent at a later time.

Even less is known about Margrett Pugg Quando. Her exact year of birth is unknown, but in 1739, when she filed a petition for relief from the need to pay certain annual taxes, she gave her age as well past 70 years (this story is related later in this chapter). By that calculation, she was born earlier than 1669, which would have made her six or more years older than Henry Quando, whose birth year is believed to be 1675. No evidence has been found reflecting where or when Henry and Margrett were purchased, but later records note Margrett as Henry Quando’s wife.4

In 1691, when he was 16 or 17 years old, Henry registered his cattle mark. The Charles County registration describes the mark as a “swallow fork on both eares and underkeeled on the right eare.”5 The registration of his cattle mark would have enabled Henry to readily identify and protect his livestock and ensure that his property interests would be respected. Even at this young age, Henry exhibited an entrepreneurial spirit and a sense of self-worth.

The main industry of the area was farming. Henry and Margrett presumably were farmers, grazing their animals on whatever acreage they could secure. The farm tools bequeathed under Adams’s will seemed targeted to the furtherance of farming, an occupation that would partially shield the fledgling but free Quando family from the daily racial insults and challenges of the age. Encumbered by limitations upon the ability of free blacks to own land, the Quandos may have indentured themselves as farm hands to white settlers for the next several years, accumulating resources to help them eventually strike out on their own. In a few years Henry’s intentions to achieve independence and self-reliance were clearly manifested. On February 4, 1695, Henry, whose name was listed as “Henry Quandoo,” less than nine years out of slavery, executed a 99-year freehold lease with Ignatius Wheeler, a major plantation owner in Port Tobacco, Charles County.6 Henry’s tract was 116 acres of land, part of a much larger tract called “Wheeler’s Folly.” The tract was just off Port Tobacco Road, a few hundred feet inside the Charles County line. The acreage was located immediately adjacent to what is now Route 301, along Mattawoman Creek. Henry’s signature on the deed was an “X.” Margrett was not a signatory, as women had virtually no legal rights at that time, and African women had no rights at all in this hostile place. In establishing a freehold secured on a 99-year lease, Henry attained the most comprehensive, multigenerational interest that someone could hold in land, short of outright ownership. A lease of this type could be inherited by subsequent generations through 1794, the natural end of the leasehold period.

Wheeler to Quando deed, 1695

Deed from Ignatius Wheeler to Henry Quando, leasing land for 99 years, Charles County, Maryland, 1695

Henry Quando probably never imagined that his securing a 99-year freehold would ever be viewed in a much larger context, that is, as a black man taking a stand. As the holder of a freehold long-term lease he may have enjoyed some civil freedoms despite the restrictions that were placed upon all black residents of the county. A 99-year lease was closely akin to actual land ownership, as by definition a freehold interest bestowed extensive rights and privileges, with voting and participation in local community activities limited to landowners and freehold tenants. But did Quando ever vote or participate in community decision making? Although institutional racism was not yet widely established, laws were being passed that restricted black men’s access to the wider community. Whether these laws translated into a denial of Henry Quando’s voting and other rights is unknown, but allowing a black man access to this level of societal participation, to help shape the direction in which his own community would proceed, is extremely doubtful.

Perhaps of more immediate importance to Henry and Margrett, gaining the freehold was their first real opportunity after manumission to put their accumulated farming skills to use on their own farm. In the 10-year period between 1686 and 1696, Henry and Margrett progressed from slavery to freedom, from dependence to self-reliance. When measured in the hostile atmosphere of their times, their advancements were monumental.

In recent times, the Quander family’s history as movers and shakers for justice and social change has been recognized. Research into that history reveals that these characteristics were not recently acquired. Rather, in significant ways this activist attitude was ably demonstrated by Henry and Margrett at a much earlier time, when they recognized they could not function in this hostile land unless they actively stood up for themselves, demanding to be afforded whatever small measures of freedom were available to free blacks in the early eighteenth century. This independent spirit and ability to earn their way was most likely exhibited during their period of servitude to Henry Adams. It is doubtful Adams would have freed them in 1686 if he thought they could not handle it. His differing attitude concerning emancipation was demonstrated by his not freeing the young male child and old woman, whom he also held in servitude, their names not even appearing in his will.

Henry and Margrett’s spirit and determination to succeed in the face of adverse odds has carried over to the present. Although most of the present generation has no recollection of why this spirit is an integral part of what it is “To Be a Quander,” at least one example is found among the records. On June 13, 1702, Henry filed a petition before the High Court of Chancery, Province and Territory of Maryland, asking the court to determine whether he had to pay an annual tax that was assessed against slave owners for the privilege of having black female slaves. His basic premise was that the tax assessment law failed to take into consideration that some of the black women in the community were free, and not profit generators for some slave owner. Moreover, Henry did not own Margrett. Henry concluded by urging that this tax law and its intended effect should be viewed as totally inapplicable to their situation.

Like other free, married women, black or white, of her era, Margrett could not vote, own real property in her own name, or even bring suit. Moreover, women of African origin were viewed as little more than beasts of burden and a revenue-generating asset because they could produce more slaves. The court’s focus seemed to be only to procure the annual provincial tax imposed upon the profits these women generated for their slave owners. The High Court of Chancery, having its own agenda to ensure that a steady stream of funds flowed into the province’s coffers, ruled that the tax was to be universally levied against all black females, whether slave or free, and directed Henry to pay up.7

Several valuable lessons were learned from that singular incident. First, knowing what the odds were, Henry and Margrett elected to try anyway, to contest the obvious unfairness of making a free black man pay an annual “profit” tax on his own free wife.

Second, their contesting the issue demonstrated their strong belief that they had rights, despite the refusal of the legal institutions to recognize them. Their activism dismissed any myths that our forebears, as a people, were docile, pliable, and complacent, and replaced such inaccuracies with a clear statement of bold action, moving into uncharted legal waters without any known precedent or likely positive outcome.

Third, despite losing this decision, Henry and Margrett Quando continued to fight, as subsequent records show they continued to seek relief through the courts. They may not have intended their actions to be a beacon for later African Americans, but that is what resulted. They are role models of men and women in the Quander family who set a strong example of African Americans taking a stand by speaking up for their rights.

Henry’s petition to the High Court of Chancery was not the only time he and Margrett stood up for themselves. My further research revealed a protracted story involving the Quando family between 1718 and 1722 that has enough twists and turns that it could be a prime time mini-series.

In 1718, a grand jury in Charles County instituted proceedings against one Ann Rannes for having a child out of wedlock.8 Although she was referred to as a white indentured servant, the child was characterized as a mulatto. Wishing to escape the harsh treatment and public humiliation she knew was forthcoming, she sought the assistance of Thomas Wheeler, the brother of Ignatius Wheeler, who had conveyed the “Wheeler’s Folly” land tract to Henry Quando in 1695. Thomas Wheeler, himself a planter as well as a bondsman, elected to prepare and sign a performance bond guaranteeing that Rannes would appear in court on the scheduled date to face the allegations of bastardizing. In the interim, he and she dreamed up a scheme they thought would create a win-win result for both of them.

Perhaps because he knew the Quando family through his brother, and perhaps because he considered Rannes as a high-risk client, Thomas Wheeler persuaded Henry and Margrett’s minor daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, to sign Rannes’s performance bond as co-guarantors of her appearance on the assigned court date. Under the terms, the Quando sisters agreed that if Rannes failed to appear in court, they would be called to perform in her absence. Had Wheeler succeeded, the girls would have indentured themselves for seven years, probably working in Wheeler’s fields. The inducement for the girls to co-sign the performance bond is not reflected in the record, but presumably they received some incentive for their agreement. Whether they understood what they were getting into is doubtful. In all likelihood they could not read; in fact, later records referred to their brother, Henry II, as illiterate.

Wheeler then arranged for Rannes to leave Maryland and cross the Potomac River into Virginia. It was a perfect arrangement: she would likely escape her punishment, and Wheeler would have two unpaid field hands for a seven-year duration. In the court proceedings Wheeler portrays himself as an innocent party, someone who has been wronged by Rannes rather than conspiring with her.

This obvious setup against her daughters was not to Margrett’s liking. That she and not Henry petitioned the court to stop the Wheeler-Rannes scheme strongly suggests that Henry Quando had died or was seriously ill before 1718. Margrett appeared without him on behalf of her minor daughters and petitioned the court to set aside this obvious fraud. Wheeler’s ability to obfuscate caused the case to drag on for years. Moreover, the colonial courts did not sit every day. Most of the judges rode circuits, and were only available to hear cases in certain geographical areas at certain times of the year. Margrett’s race and gender almost assuredly contributed to the length of the case. The judges and members of the local old boy network may have assumed or simply hoped that she would give up and not pursue her petition.

But they underestimated Margrett’s determination. Unlike the so-called peer group that was sitting in judgment of her and Wheeler, she knew what it was like to be a slave. She was determined that her daughters would not be indentured. It was not until June 6, 1722, almost four years after the proceedings started in Quando v. Wheeler, that the court fully recognized the significance of Wheeler’s deceitful actions and the nature of his intentions. The deceit was set aside, with a supplemental award of 2,148 pounds of tobacco to Margrett as punitive damages and costs.9

The victory was slow in arriving, but it must have been sweet when it was eventually realized. Margrett Quando prevailed at the trial, once again leaving a clearly defined legacy of hope and determination for successor generations to find, be inspired by, and emulate. The moral victory’s returns were incalculable. The myth of the docile Negro content with his or her lot in a hostile America was once again shattered. A black woman seeking and obtaining justice was at best a difficult task, and most often a frustrated, unsuccessful effort, especially when attacking the credibility of a white male property owner of significant visibility and connections. During my research I met Walter Ball, a direct descendant of Thomas Wheeler. Ball’s research into the Wheeler family history had revealed that Thomas Wheeler, whom he called a “thief and a scoundrel,” was as deceitful, dishonest, and unreliable as his brother, Ignatius Wheeler, was benevolent, trustworthy, and honorable. I learned from Ball that Thomas Wheeler was regularly sued by plaintiffs alleging that he had committed some wrong against them.

Margrett’s victory at the bench was short lived. In the following year, 1723, Margrett, noted in the record as “a free negroe woman,” was faced with a different dilemma. In that year she filed a petition seeking relief from a tax levy that had been placed on herself and her daughters, noting as the basis of the petition her age, which was not specified, and her lack of monetary funds with which to pay the tax. The petition was denied. Margrett’s financial problems suggest that successfully operating the 116-acre freehold may have been too difficult. The earnings from the Quandos’ farming efforts were in all likelihood not enough to ensure a decent living and meet all expenses. Having to meet tax levies only added to the hardship.

Although the full nature of the unsuccessful 1723 petition remains clouded, Margrett’s tenacious spirit set the tone for yet another legal victory. She petitioned again in 1724, this time with a fuller explanation of why she believed herself entitled to relief from the annual levy.Crucial in her petition, she sets forth that she had learned that by reason of the acts of the assembly of the province, she and her daughters were not to be taxed. Nevertheless, she has paid the taxes over time with great difficulty, and seeks relief for the present (1724) and the future. The court ruled in her favor. Thus, as free persons of color, Margrett and her daughters were not required to pay the annual total levy in the amount of 616 pounds of tobacco from that date forward. No reference is noted about any refund for taxes previously collected in contradiction to the acts of the provincial assembly.

The relief obtained from the levy in 1724 proved ephemeral. Other petitions were filed in 1727, 1733, and 1739 seeking the same relief, but not yielding consistent results.10 These assessments were apparently not levied every year, but when they were, Margrett did not hesitate to seek relief from them. In her August 1733 petition on behalf of herself and her daughters, she noted that the assessments had not been sought for the prior two years. Allowed to go before the court to express herself, her petition was once again rejected. The sole reason noted was that “Margaret” Quando’s claims to be “poor” and in “poor circumstances” were characterized as unproven in the record.

Henry and Margrett boldly initiated action on their own behalf. Margrett learned early that dogged persistence in pursuit of justice sometimes pays off, and she pursued relief through the courts until someone finally agreed with her. Willing to take chances and ply uncharted jurisdictional waters, they both demonstrated that African Americans were no less than other Americans and deserved a fair measure of justice and consideration. Although the victories were few and not consistently obtained, several small and successful steps were taken. The Quandos, even if unwittingly and unintentionally, laid a firm foundation to be later recognized as African American leaders.

CHAPTER 2

Bastards Or Babies?

Henry and Margrett had at least three children: a son, Henry, Jr., whom I’ll call Henry II; and daughters Victoria, Elizabeth, and Mary. Court records show that each of their children received substantial judicial attention, most of it unfavorable. Still, their legal encounters created a record for me to study and a means of painting this picture of the enduring African American legacy. Although Henry II’s recognition was in business and entrepreneurship, analogous recognition was denied his sisters, at least two of whom distinguished themselves by having illegitimate children.

Having children out of wedlock was strictly forbidden. Situations in which an interracial child was born of such a relationship were dealt with most severely, although enforcement was not uniform. Even if the man and woman had strong feelings for one another, interracial marriage was not legally possible in the early eighteenth century, and would be denied until the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the 1967 landmark case Loving v. Virginia invalidated laws forbidding black-white marriages.1 Typically, when a child was born of a black woman and a white man, the woman stood to be severely punished, while the white father usually escaped any liability for his actions. In some cases, child support was required to relieve the public treasury of the need to take care of these highly scorned mulatto bastards. Conversely, if the woman was white and the man black, both of them were harshly disciplined.

That the races were created separate and apart and should remain that way was a myth that was sorely tested.The corollary myth that no white man in his right mind could desire a black woman was consistently perpetuated, even though ignored whenever convenient. It was also officially unthinkable that a pure and innocent white European woman could even consider allowing herself to be touched by a licentious and lusty black man, much less allow him to have intercourse with her. It must have been rape! In spite of these social taboos, many obviously mulatto children could be observed within just a decade or two of the introduction of Africans into Virginia in Jamestown 1619. The undisputable and marked presence of mixed-race births was the predictable result of a significant amount of sex forced on black women by white men.

A documented example of the uneven treatment accorded to a free black woman and a white man began in 1705. The Court and Land Records of Charles County report that in that year a grand jury indicted Victoria Quando for having a child out of wedlock. She appeared in the court on January 8, 1706, and entered a guilty plea. Her sentence was 10 lashes at the whipping post and a fine, which her father Henry paid on her behalf. The case reads as if having this child outside of marriage was solely Victoria’s fault. No reference is made to the father’s identity, but the child’s racial classification as mulatto makes clear that the father was white.2

The frequency of the term mulatto tells a story in itself. I make no claim to having studied every document on the subject that appeared in the court records of the era, but I reviewed at least 35 documents that clearly indicated that interracial couplings were more common than the society at large cared to admit, frequently followed by the birth of mixed-race children. Such results were widely frowned upon, with the all-male white judges of the courts taking it upon themselves to be the enforcers and standard setters of the public morals. Inspired by the white community’s all-out effort to deter interracial sexual relationships, mulatto children were an ongoing irritant and issue of significance to the local judicial community. The determination of the whites, generally the plantation owners themselves, to discourage lower-class whites from having affiliations and especially sexual relations with blacks, slave or free, caused them to monitor as closely as possible the personal behavior of their own slaves and the lesser members of Maryland society. And although it is no secret that the plantation owners were often the biggest offenders, regularly impregnating their own slaves, not all mulatto children had white fathers and black mothers.

Although Anne Rannes had a baby by a black man (Chapter 1), far better known is the story of Eleanor “Irish Nell” Butler, who in 1661 migrated to Maryland, where she was indentured to Lord Baltimore. Having fulfilled the term of her indenture, in 1681 Nell took Charles, a black slave, as her husband (having no last name, he took the Butler surname). With the law not stabilized on the issue, Nell was forced into slavery, and all of her mixed-race children were likewise born into slavery. Despite laws that forbade a legal marital union between them, I am certain that no one could convince either Nell or Charles that they were not married. Devoted, committed, and determined, their relationship and its multigenerational Butler progeny are well recognized throughout Maryland and the Washington, DC area, and Nell and Charles are still fondly recalled today. No legal proscription could impede their personal association.

After Victoria Quando’s 1706 indictment for bastardy, Henry and Margrett and their children disappear from the record books for a while. But in 1724, when Margrett was petitioning the court for tax relief, Mary Quando (sometimes referred to as “Maria Quandoe”) was indicted on the same offense as Victoria.3The records for this period are sparse. Based on a formal complaint filed by Thomas Middleton, Constable of the Piscataway Hundred, located in southern Prince George’s County, a grand jury sitting in Marlborough Town accused Mary of “having [an] abase born child.” The proceedings were reported as follows:

On the fourth Tuesday in March, 1724, Maria Quandoe, having been previously summoned to court, appeared in the custody of Sheriff Thomas Middleton, and upon being confronted about the matter, stared that she would not contend the matter, submitting herself to the grace and mercy of the court. A decision was then rendered by the jury that Maria should be fined or suffer corporal punishment according to the Act of the Assembly in such cases, provided that if she did not pay the fine or procure anyone to undertake to satisfy the fine for her, she was to be then taken by Sheriff Philip Lee, Gentleman, to the whipping post to be given on her bare body 15 lashes well laid on so that blood appears.4