Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

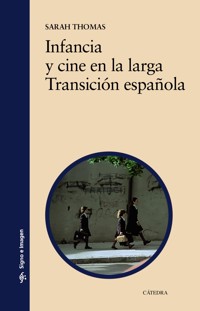

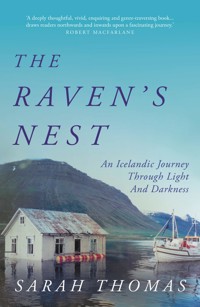

'Fascinating' -Robert Macfarlane, author of The Old Ways 'Truly a thing of wonder' - Kerri ní Dochartaigh, author of Thin Places 'Lyrical [and] thoughtful' - Cal Flyn, author of Islands of Abandonment Visiting Iceland as an anthropologist and film-maker in 2008, Sarah Thomas is spellbound by its otherworldly landscape. An immediate love for this country and for Bjarni, a man she meets there, turns a week-long stay into a transformative half-decade, one which radically alters Sarah's understanding of herself and of the living world. She embarks on a relationship not only with Bjarni, but with the light, the language, and the old wooden house they make their home. She finds a place where the light of the midwinter full moon reflected by snow can be brighter than daylight, where the earth can tremor at any time, and where the word for echo - bergmál - translates as 'the language of the mountain'. In the midst of crisis both personal and planetary, as her marriage falls apart, Sarah finds inspiration in the artistry of a raven's nest: a home which persists through breaking and reweaving - over and over. Written in beautifully vivid prose The Raven's Nest is a profoundly moving meditation on place, identity and how we might live in an era of environmental disruption.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 458

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Sarah Thomas’ lyrical, thoughtful prose takes us on a journey, both physical and emotional, to the far north – a region about which stories are increasingly essential, especially from those who live there. One senses her filmmaker’s eye in her crisp visual imagery, and in her careful portraits of both people and place.’

Cal Flyn, author ofIslands of Abandonment

‘The Raven’s Nest asks what it means to belong to a place from which we do not originate. It considers Icelandicness and proximity to it. Both anthropological and tender in detail, Sarah Thomas recalls an immersion that sometimes feels like drowning, at others a rush on swell to the shore. Her skills as an anthropological documentary maker come across on the page, but she is a participant in this story, present and implicated in what it means to dwell between tongues, cultures, landscapes and geological timescales.’

Abi Andrews, author ofThe Word for Woman is Wilderness

‘The Raven’s Nest is a story of many stories, nested together: the making and ending of relationships. Those chance meetings across wide unlikely spaces, how they spin for a while and how we can bear to let them go. But boil that down further and I would say it has much to say about chance, and taking chances, and being open to chance – and also the chance trickery nature plays on us. And that feeds into where stories come from, and whose stories we can tell. Sarah Thomas evokes characters and the culture, a sense of time and the landscape in beautiful prose which makes my brain do cartwheels.’

Nancy Campbell, author ofThe Library of Ice

Sarah Thomas is a writer and documentary filmmaker with a PhD in Interdisciplinary Studies. Her films have been screened internationally. She is a regular contributor to the Dark Mountain journal and her writing has also appeared in the Guardian and the anthology Women on Nature, edited by Katharine Norbury. In 2020, she was nominated for the Arts Foundation Environmental Writing Award. She was longlisted for the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize and shortlisted for the 2021 Fitzcarraldo Essay Prize for the proposal for this book. This is her debut.

THERAVEN’SNEST

An Icelandic Journey Through Light And Darkness

SARAH THOMAS

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2023.

Copyright © Sarah Thomas, 2022

The moral right of Sarah Thomas to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Some of the names in this book have been changed to protect the privacy of people and places. Versions of some chapters previously appeared in Dark Mountain Issue 7, Caught by the River and Ós. ‘A floating house’ © G. Kristinsdóttir; ‘Seal’ © H. Guðröðarson; ‘Seal looks back’ © N. Pilters.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 671 4

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 670 7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To the ravens, for making, unmaking and remaking the world.And for the light; always the light.

Contents

Breaking Up

Landing

Shift

Tónleikar – Concert

Fjallafang – Embrace of the Mountains

Mataræði – Diet

Gíslholt

Seal Wife

Að smala og að slátra – Gathering and Slaughtering

Gos – Eruption/Gas/Fizzy Drink

Flytja – To Move

Krummi – Raven

Bogguhús

The Frozen Bell

A Floating House

Trúlofun – Engagement

Selur – Seal

Þakið – Roof

A Walk in My Valley

Göng – Passage/Corridor/Tunnel

Að snúa – To Turn; Snúið – Complicated

Innflytjandi – Importer/Immigrant

The Strangest Silence

Svartfuglsegg – ‘Black-bird’s-egg’

Hvalurinn – The Whale

Seljavallalaug – ‘Shieling-plains-pool’

Herring Adventure

To Hell and Back

The Raven’s Nest

Sjóndeildarhringur – Horizon

Acknowledgements

Breaking Up

August 2014

I am sitting in the kitchen of my old, corrugated-iron-clad house. Underneath me, 800 kilometres to the southeast, the earth has been breaking up since the evening I parked up out front, one long week ago. I arrived as the day dimmed, relieved to have the hours of rock and sea and fog behind me – months of anticipation giving way to reality. Then, 8 kilometres under the ground, below a distant glacier, unseen but detected by geologists and their myriad instruments, a tremor swarm began. I heard about it on the radio the next morning as the late summer sun poured in through the large windows. There had been 250 earthquakes during the night.

When the news broke, I laughed at the consistency with which my comings and goings between England and Iceland seemed to coincide precisely with weather changes and volcanic activity. The eruption of Eyjafjallajökull – the Icelandic volcano that nobody could pronounce, which closed European airspace in 2010 – was preceded by a lesser-known smaller eruption on Fimmvörðuháls. That had begun the day I arrived in March 2010 and ended the day I left, with the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull. I had been on one of the last flights for many days, separated from my husband by a cloud of ash.

Now, each day, there are more earthquakes, and a crack has grown to 50 kilometres long in a week – still invisible as it rips below Vatnajökull, the largest glacier in the country. Every day, almost every hour from 7 a.m. till 10 p.m., the radio news announces the latest earthquakes, usually in the region of 1,000 per day now, the strongest recently reaching 5.7 on the Richter scale. I hang on every word, pretty sure an eruption will follow, and not knowing whether I should prepare myself to leave before I risk getting stuck here.

The first few days of this trip were difficult. My destination – clarity in an uncertain marriage – is far from guaranteed. I have mostly been here alone. Well, with my cat. And a brief but intense lifetime of memories of this place to process – some dark, some joyful.

This house and I felt asynchronous when I walked in. It looked much the same as it did when I left, all those months ago. I had asked my husband, Bjarni, for our cat to be here when I returned. He made sure he was at the house when I arrived and was cooking lamb in the kitchen, almost like nothing had ever happened. The only visible evidence of time passing was a few kind notes from tourists who had come and enjoyed this ‘thing’ we had created, while we did not live in it ourselves – this ‘bohemian Arctic hideaway’, this ‘romantic retreat’ – while we had tried to figure out how and where we could live together, and failed.

I feel the need to do something physical, and aesthetic, to mark the change. In front of me, I peel decades of wallpaper, hessian and old newspaper from the walls in my study, to get back to the bare bones of this place – this wooden kit-house from Norway, erected in 1902. We know the name of the person who erected it, and that his son’s wife lived in it for 70 years before we became the current owners. It may be that couple’s history I am peeling away now, to reveal the time-darkened honey-coloured pine panelling it was made with, before it became fashionable to mask it with paper: a well-travelled wood, for there were no trees here big enough to build with. The final layer is The Weekly Scotsman from 19 June 1909. How did that newspaper end up in this house just below the Arctic Circle?

Old news, which one day mine shall also be. Trees, wood, paper, words – they vanish as they form.

Old news, which one day this imminent eruption shall be, whether it happens or not. For now, I try to embrace the Icelandic way and take each day as it comes. To stay put and do what I came here to do.

The international news recalls the ‘chaos’ caused by the 2010 volcano that nobody could pronounce. Laufey, my old boss from the flower shop, dismisses these tremors as a ‘media sensation’. I enjoy her humanizing of this seismic activity; the suggestion that somehow it is a protracted form of attention-grabbing, like a celebrity affair. My neighbour Mæja tells me, ‘There’s nothing you can do but wait and see. It’s the same as driving a car in a big city. Sure, something might happen but that doesn’t stop you from driving.’

Bjarni and I find each other much easier to get along with than we expected. The connection is heartfelt and strong, but we still know we must go our separate ways in order to become ourselves again. It is like living inside a dream sequence: the backdrop is the same, he is there, he is calm and almost happy. The cat is curled up on the chair. It’s like it used to be, but it’s not. Neither of us can live in this house anymore. He cannot bear the reminders of our broken union hanging on every picture hook and in every colour we painted the walls. I cannot bear the long months of darkness and the separation from the rest of the world – a crucible for unreconciled pains. I have returned to live in my own country, where at least I know that the sun will rise above the horizon every day. I have not stood in this house to be prodded by these hooks and these colours, until now. I have traversed rivers of grief to arrive here, and now we must make new memories.

I still love him and yet I cannot smell him anymore. I try, but I find nothing. It disturbs me. It is one of the foundations on which I committed to this unlikely path. Have sorrow and distance altered our chemistry?

‘Can you smell me?’ I ask him.

‘You smell like a distressed mink,’ he says, without irony or insult. For him, it is simply a fact. Like an eruption will be a fact. And a divorce. There is nothing I can do but accept our fate.

* * *

I accept it and we go together to initiate proceedings. On that day, of all days, there is a region-wide phone and internet drop-out, apparently nothing to do with the tremors. The majority of administration at the Sheriff’s office, which handles such proceedings, is done online. For as long as this drop-out continues, there will be a shutdown of the region’s bureaucratic processes. There is nothing we can do. I leave tomorrow. I shall leave still married.

As I spend my final hours in Reykjavík, the news breaks that the crack has become visible, and the glacier is collapsing. I make my flight back to Edinburgh.

As I trundle my bulky luggage – much of it chattels from my Icelandic study – along North Bridge in the city dark of 1 a.m., across the tracks of Edinburgh Waverley station, my eye is caught by the gold up-lit stone lettering emblazoned across the façade of an imposing turn-of-the-century building: The Scotsman. I slow to a halt as I realize that it is in this building that those words were created – the old news that I had been peeling off my walls – before they made their way across the sea to my house, and my study.

The next day I receive an email from Bjarni:

The volcano erupted at two minutes past midnight the night you left.

Landing

May 2008

My neck aches as I react to the ‘bong’ prompting passengers to fasten their seat belts. My face has been pressed against the oval window for thirty minutes straight, turning only briefly to say, ‘tea, please’. Beyond the condensation of my breath and the delicate ice crystals forming on the outside of the window, I have been looking out at a translucent blue sky that seems stretched thin by the weight of profuse sunlight. Beneath it, the sea is a choppy teal blue as if painted by a stippled brush and the shoreline meets the mountains frankly. Their opaque indigo bulk rises sharply and they are flat on top as if a giant has taken a sword to them. It is an Arctic palette, an infinite blue, and the landscape appears as wild and unsullied as Earth does from space. Though I know pristineness is an illusion in our times, for the moment I am enrapt. I am heading the furthest north I have ever been: sixty-six degrees latitude. Even in late May, snow swirls on the mountaintops and rests in shaded hollows. Since lifting off from Reykjavík I have not noticed any other cities or even aerial towns; only settlements I would describe generously as villages, and no more than three of them.

Having started the journey in London, I am on my way to the small town of Ísafjörður – the ‘capital’ of the Westfjords – in the top northwest corner of Iceland, which for reasons none of the delegates will fully understand, is the unlikely and awe-inspiring location for a conference of visual anthropologists. I will be presenting my MA graduation film After the Rains Came: Seven short stories about objects and lifeworlds, an observational documentary I made in Kenya, where I spent the latter part of my childhood and adolescence.

Observational documentary: the ‘fly on the wall’ style where the footage works to suggest that the filmmaker is not there at all. A film shot on the Equator, brought to the Arctic. The view from the plane’s window could not be more different to the world of my film: the cracked earth, coloured beads and giant euphorbia trees of Kenya’s Samburuland that will soon be projected on a screen down there somewhere.

I have been invited to stay with some friends of a friend, and as I gaze out at the wilderness, I feel fortunate to have connections in this remote place. I wrote to them a while back thanking them for their kind offer of a bed, and in response received ‘directions’: a photograph taken from the side of a mountain, looking down onto a long narrow fjord flanked on the opposite side by another steep-sided mountain – a trough of rock filled with sea. A spit curled out from the foreground to part way across the mouth of the fjord, forming a sheltered harbour. Brightly coloured houses were clustered on the spit and the few other flat surfaces of land. Their spread was contained by the clutch of the landscape, as if gravity itself pulled the houses towards the sea. Where construction ended, wild nature abruptly began – loose boulders on tussocky heaths and funnels of scree sloping up to terraced cliffs of basalt. This was altogether different from the patchwork of green squares and vast masses of concrete that is England from above. Over on the far shore at the bottom of the fjord they had drawn a yellow circle, and the word ‘Airport’. Towards the foot of the spit was another yellow circle: ‘Salvar and Natalía’. Their house was oxide red – I could see that from the photograph. My rational city brain was slightly wary of the lack of further information, but my intuitive self could see that this was the only information I would need. I liked these people: visual and concise.

As the twin-propeller Air Iceland plane suddenly banks sharply left, I recognize that this is that fjord, that spit seen from the other side. I imagine my hosts standing there taking that photograph, as I align its viewpoint with what I can see. I realize I might even be able to spot the house I am going to. My search for it is quickly replaced by alarm at the proximity of the wing tip to the mountain. It is a very close shave indeed, and a good thing they are standing there only in my imagination. I briefly look around at the other twenty passengers on this packed flight and cannot fathom how some of them are reading a newspaper. This moment is both frightening and phenomenally beautiful. We descend to the bottom of the fjord and bank steeply again. Somebody has mown a large HÆ into their hay meadow – a greeting to be seen from the sky. We land and bounce onto the airstrip facing towards the mouth of the fjord, from which we have just come. ‘How is that even possible?’ I think to myself. I would later learn that Ísafjörður is one of the most challenging airports in the world in which to land.

We disembark into the miniature single-storey terminal where passengers are waiting to board the same plane back to Reykjavík. We mingle. There are two flights here a day, cruising back and forth across this lava, these mountains and these fjords: Reykjavík – Ísafjörður – Reykjavík – Ísafjörður – Reykjavík. Passengers departing Ísafjörður don’t need an app to tell them if the flight is running on time. They just look up in the sky when they hear the engine rumbling and hop in their cars to curl around the bay to the airport, playing plane chase. I would later learn that the radar tower operator is also a carpenter in town, and simply cycles over to the airport when a flight is due, then returns to work when he has seen the plane safely off again.

It turns out that several fellow delegates are on the same flight and there is a coach waiting for us outside. White-bodied birds I have not seen before wheel, combative like throwing stars, above the car park showering the air with cries of kriiiia kriiiia. The passengers wrestle their black luggage into large four-wheel drives. The mountains tower above us and insist that we are small. You can spot those who do not live here: their mouths hang agape over the necks of their Gore-Tex jackets, and their luggage has lost all its importance. The locals seem to have developed an immunity to the landscape’s power, but I imagine it is more complex than that.

We board the coach and a tall frowning man with a grey side parting and a shiny face fusses and breaks intermittently into nervous laughter. ‘Hæ. I’m Valdimar,’ he greets us repeatedly. He is clearly the one in charge, but it looks like this is the most people he has had to organize in a while. It is hot, and I have come only with jumpers. The sun feels near. It is bright and beats on me through the large glass window, as if curious and eager to illuminate everything it can. I drink in the scene through squinted eyes and feel both sleepy and enormously awakened.

We round the bottom of the fjord, passing on our left a grid-like housing development and a supermarket with gaudy signage of yellow with a bright pink piggy bank: Bónus, it is called. Behind it all is a long, lush valley lined with lupine and speckled with brightly coloured wooden cabins. Midway up the valley I can make out a large waterfall that in another place would be reason enough to come here, and a small square plantation of some kind of pine that Valdimar refers to as the local ‘forest’. There is a long, man-made sharp-edged ridge separating that valley from the buildings along the fjord’s edge and he tells us that it is an avalanche guard. In the harbour lagoon to our right, flocks of eider ducks bob among reflected impressions of the sun-glowed mountains – morphing orange and green fragments floating leaf-like in the black glassy water. We pass a scattering of houses, then the town proper seems to begin. Valdimar takes the microphone again and points out in quick succession a kindergarten, a school, an old people’s home, a hospital and, across the road, a church and cemetery.

‘I suppose they have to be ergonomic with town planning here!’ an Italian academic in the seat behind me chuckles. ‘Look, a whole life in 500 metres.’

As we approach the spit on which the oldest part of the town is built, I see that the houses are all clad in brightly coloured corrugated iron, with differently coloured iron roofs. In just one street I see cornflower blue, deep red, egg yolk yellow, black. It gives the town an air of playfulness – I imagine the people here to be happy and daring. The coach slows to a halt by the church and I take my photo directions to Valdimar. It is a map made for a bird or a hiker at height. I am at the wrong angle here.

‘Do you know where this house is?’ I ask him. ‘That’s where I’m staying.’

‘Whose house is it? Salvar and Natalía? Ah yes, I know them.’

He reaches for his mobile phone and scrolls for their number. He doesn’t have it. He inspects the photograph a little more closely. ‘… Sólgata, Hrannargata, Mánagata, Hafnarstræti… Ah, that is this one.’ He points at the street we are on. That was easy.

Twenty metres later I am standing in front of an oxide-red house, conjoined with a leaf-green house painted with a mural of giant dandelions. From what I have seen of Icelandic homes from the outside, it seems to be typical to make displays of ornaments in the windows, to delight those walking past on the street, and perhaps to give an inkling of the people who live inside. In the moments between my knocking and the door being answered, while I imagine what Salvar and Natalía might be like, I notice on their windowsill a tall glass jar filled with strangely shaped birds’ eggs I have never seen before, each a different shade of aquamarine, green, duck egg blue, turquoise, ivory: an exquisite non-tessellation of otherness. For reasons I cannot explain, they touch me deeply. Can you be reminded of something by an entirely new form?

Salvar and Natalía have warned me by email that, though they are happy to put me up, they are extremely busy preparing to leave for the highlands, for their summer job running a ‘mountain shop’. This titbit of information has made me curious about their lives. The idea of a seasonal existence makes so much sense to me. I am prone to get into deep conversation when something interests me, but in the circumstances, I prepare to drop my bags and make myself scarce as quickly as possible. I am greeted at the first knock by two smiles and a welcome large enough to fill the reception room that seems to be dedicated entirely to this purpose, and to the storage of a sizeable rail of coats, hats and scarves. After putting down my bags and exchanging greetings, the blue eggs are one of the first things I ask about.

‘Ah, svartfuglsegg,’ says Salvar. ‘Yes. They are very beautiful.’

He gives me one to hold. It has been drained and has a hole at either end.

‘Svart-fugl means “black-bird” but it’s not your kind of blackbird. It’s the word for the seabirds that are black. There are several kinds. This one is langvía. “Guillemot”, I think you call it.’

I turn it in my fingertips and hold it up to the light. It is at once strong and fragile, pointed and round, simple and infinitely complex – a collection of paradoxes in ovoid. A thick strong shell the colour of turquoise, a perfectly rounded base that sits so naturally in the palm of my hand. Sides that rise gracefully like the steepest of volcanoes into a sharply rounded point. An archipelago of burnt umber marks speckled over an ocean of delicate blue. It is as though it has been clutched excitedly by a tiny-fingered beast covered in paint. Holding the egg in that moment, I feel within me a tectonic shift so deep that only the most perceptive would notice.

I have been back in England for ten years, but I find my childhood in Kenya bubbling unexpectedly to the surface. Our lives were porous to wild creatures. I was often immersed in the textures, scents and soundscapes of savannah or scrub or ocean. Even at home in the then forested suburbs of Nairobi, Sykes’ monkeys would descend on our garden, and the most audacious would sneak into our house to steal pineapples and mangoes. I was taught never to smile at monkeys because bared teeth are a sign of aggression. Once, on a school camping trip, I woke to pee in the night and unzipped my tent onto a galaxy of buffalo eyes reflecting my headtorch.

But, having moved to Kenya from England, that wild had always remained exotic to me – other. Or perhaps it is I who remained other to it. It was the nature seen in wildlife documentaries, not mine. The potential dangers posed by the wildlife – from megafauna to malarial mosquitoes – meant my relationship with it was often about protecting myself from it. I could be in awe, but I could not bring it close. Here, all of a sudden, I am holding the wild in my hands in a front room on an island in the North Atlantic, an ecology continuous with the UK’s, where I have so far spent my adulthood. This is a wild to which I can relate: somehow familiar though not yet known. It is not trapped behind glass, or enclosed within a national park: it lives in the world. And for better or worse it is in my hands because it is used. The eggshell is hollow because the egg has been eaten.

‘Kaffi?’ Natalía offers.

It will be the first of many cups drunk around the large table in their triple-glazed conservatory; their Vetrarhöllin (‘Winter Palace’) as they proudly call it. Today, there is enough time only to make a quick life-sketch of each other. They tell me they are artists. Natalía is from Moscow and Salvar is an Icelandic farmer’s son. They met at art school in Germany. They had noticed each other and Natalía asked shy Salvar out for a cup of tea. ‘It is the longest cup of tea in history. We are still having it!’ Natalía giggles. They came to the Westfjords to live alone on Æðey, a small island near here, having heard on the grapevine that a job was going reading the weather instruments which served the region. They knew they would be inspired by the solitude and the nature and have time to develop their artistic practice.

After seven winters of living that life, alternating with their summer job in the highlands, they decided to be part of a community on the mainland and chose Ísafjörður, this regional capital of about 2,600 people. From the island, Salvar came ‘shopping’ one day to find a house. ‘Get something cheap and outside the avalanche zone that we can make nice,’ was Natalía’s only instruction. He found this modest red house on the spit across the fjord, the sea at either end of the street. They got such a good deal, they believe, because the locals were so grateful for the ‘hardships’ they had endured living alone on an island. Salvar chuckles. ‘Oh the “suffering”! We loved it.’ After months of renovating, the neighbour put the adjacent house up for sale, which they also bought.

‘This house is our life plan – as long as the rising sea levels don’t get us first,’ Salvar says with a healthy dose of realism. ‘So, there is plenty of time to renovate slowly. We are not rich, but we are happy.’

‘We won’t do anything with the next-door house for ages. But one day it will be our studios.’ Natalía’s voice is like a song. ‘That’s why we’ve painted huge dandelions on it, so at least it looks beautiful. First flowers of summer. Look!’

There is a hummock in their back garden, overflowing with dandelions in the long grass. ‘That is an elf hill,’ said Salvar. ‘Isn’t it beautiful?’

Between June and September each year, Salvar and Natalía tell me they go to the highlands to a place called Landmannalaugar to run a shop, housed in two vintage American school buses, which provides food, essentials and, of course, coffee to hikers and day trippers. That is why they are particularly busy now, packing and ordering supplies before going south in two weeks’ time. That is as far as we get for now.

I show them the programme of films for the conference – documentaries from all around the world. ‘Æi! Why do they never advertise these things?’ says Salvar. ‘It is so frustrating. It’s not often we have something so interesting happening in our town.’ They promise to come to my film and will try to find time to see some others. We drink coffee and chat for at least half an hour before I realize it is time to go and register at the conference, and Salvar and Natalía remind themselves that they are busy preparing for the summer.

I sense immediately that we delegates are interlopers in this place, this life; that visitors’ affairs are very separate to local ones. The visitors arrive, mostly once winter is over, with the star-shaped birds. They are equipped with their global perspectives and their brightly coloured waterproofs, feeling, as I do, that they have made it to the edge of the world. But for the people here, this is not an edge. This is their centre. If you were to stand on the pebble beach at the end of Salvar and Natalía’s street, looking out across the mouth of the fjord to the mountains and glacier beyond, you too would feel that the rest of the world was somewhere very far away, and of seemingly little relevance – but undoubtedly having an impact on this fragile island. I feel privileged that, by staying with Salvar and Natalía, I may get to stand at the shore’s edge and listen to the tide a while; to stand where the subtler levels of Here and Elsewhere mingle, not visit Iceland through a window.

Shift

May 2008

Over the course of a few days, as the sun didn’t set until around midnight, my late-night conversations with Natalía and Salvar took me deeper into this world and their place in it. Their version of ‘busy’ was quite different from mine. There was always time for ambling conversation. When I am busy, I barely have time for myself, let alone others. And especially not for the kind of thinking that curls like smoke from a low fire. Even in their busyness, life seemed to be about meeting the day to see what it had in store for them, rather than imposing plans on it. Of course there was a ‘to do’ list, but it was mutable, shaped by what else presented itself.

In a different, much busier way, growing up in Kenya had shown me that planning was almost futile. Our life was chaotic and never ‘on time’ because of our resistance to what presented itself; because of a misguided sense that life was controllable, regardless of the consistent failure of this approach. My parents and other expats, hardwired by their conditioning, seemed to find this intensely frustrating at times. The Kenyans I met seemed more inclined to improvise their existence than design it – some of them out of necessity. And a disregard for modern Western timekeeping was commonplace. Both made a strong impression on me. This idea that we get to decide what the day is for; that we can plan and control everything; that we run to a schedule: I can see now that it is a behaviour I have learned in England or through Englishness. It is an extractive mindset. But for a brief period during my childhood, a glimmer of another way to be became visible.

As a child in Nairobi I noticed, too, the expat community of which I was a part would go to great lengths to create an island of ‘home’ in spite of the context: furniture made from African hardwoods in the style of European antiques, Women’s Institute mornings, country clubs. At that age I found it surprising. I had imagined that if we were moving to Africa our lives would look and feel more African, whatever that meant. I suppose the impulse to replicate the rhythms, habits and aesthetics of home in a strange place is a natural one, perhaps as a way to anchor oneself. At first, I simply felt uprooted. Because I had just turned eleven when we moved there, I did not yet have a sense of who I was. I was a sponge.

Looking back, my parents’ ambitions to create a stable home life were impossible to achieve in the way they might have wished, underpinned as they were by the inequality embedded within our situation. We and other expat families certainly enjoyed a better quality of life than we would have back home, but the question ‘at whose expense?’ wasn’t one that was asked.

Once things had settled down and I felt safe enough, teetering on the cusp of adolescence, I was thirsty for influences and wanted to drink from the pool I was in. My home life was somewhat at odds with that adolescent self who was becoming an adult – this adult. I was so curious to peer over the walls of my privileged ‘island’ – a beautiful house with bars on the windows in a walled compound patrolled by a night-time security guard – to mingle with the place itself. But I grew up being told that what was outside those walls was dangerous.

I had wanted to learn Kiswahili at school to feel the place in my mouth at least. But in a quirk of the British education system under which I was taught, only those who had failed French, which was compulsory, got to learn Kiswahili. I was never immersed in it. It wasn’t essential because ‘everybody’ spoke English. I did not understand back then the histories and forces of colonialism and neocolonialism which play out in these facts – Kiswahili relegated to the bottom of the pile in its own country by a private education system which is a legacy of the former colonizer. A system in which, in Geography, we learned the names and locations of UK motorways and not the dazzling topography of the Serengeti on our doorstep.

I found the segregation between expat life and the country in which that life took place infantilizing, disempowering. By twenty, I had travelled much of the world alone and thrived on building relationships with the people I met. But in Kenya I felt afraid to travel and encounter people in the same way, mainly because of the narratives of danger that had been a staple of my upbringing. No doubt the danger existed, but there was much else I was missing. Making the film that I had come to Iceland to show had been a turning point. It was the first and only attempt I had been able to make to meet Kenya as I wanted to meet it. Returning as a twenty-six-year-old visual anthropology student, ignoring warnings from other expats, I had taken a bus alone with my video camera to Samburuland, a region in north central Kenya, to shoot my MA film.

I had arranged to spend two months living with a Samburu family with whom a friend of my parents had a long-term connection. I happened to arrive with the first heavy rains in four years, which for a cattle-keeping people means everything. In recognition of this, I was given a Samburu name by Nkoko, the matriarch of the household: Nashangai – ‘the one who came with rain’. This status, fortuitous as it was, softened the barriers to our connection that existed because I didn’t speak Kiswahili, or their own language, Maa. I learned what Maa I could, and hired one of their sons, Lkitasian, as an interpreter. And we all learned to relate in other ways: joking, mime, storytelling, making.

I’m not sure I will ever completely understand the complexities of my discomfort around my family’s presence in Kenya, but in Samburuland I never felt unsafe. Utterly confounded, sometimes. In complex relations because of whiteness, gender, age and marital status – always. In danger, only once, when we stumbled upon an elephant – a mother with calf – and had to run away as she charged. Alive to the world? Very much so.

There was something in this corner of northwest Iceland that reminded me of that aliveness: a life unmediated by… what? Power? Expectation? A direct relationship with one’s surroundings, in this case free from the weight of potential threat or feelings of inequity. With time and light untethered, immersed in a more reciprocal way of being with the world, it was as if I was being made aware of a former and potential self all at once, and of how much I had been sculpted in the meantime by capitalism’s numbing agendas of progress and productivity.

For Salvar and Natalía, life was evolution and improvisation: a matter of cause and effect with a philosophy grounded in experience, blended simultaneously with an acceptance that you never know what is going to happen. They were clearly quite self-sufficient but welcomed new ideas. The way they talked about life made me feel there was something about this place that nurtured experiment. Ideas were tested out and approached playfully: something might not work but it wouldn’t be deemed a failure. It contrasted with the well-planned output-driven culture that I was a part of, which was reluctant to admit when something was not working, let alone change it. This approach to life landed in my stomach, not in my head, and it fluttered.

Their former role on Æðey – ‘island of eider ducks’ – an otherwise uninhabited island 25 kilometres off the coast, had required living on a small farm. They took weather readings five times a day and fed the animals. Once a week, provisions would be brought by the post boat, and that was, for the most part, the only human contact they had. Theirs was an important role – the safety of the local community depended on it: everyone’s lives were ruled by the weather here, not least the fishermen on whose catch the economy largely depended. Yet finding anyone who wanted to live alone on an island had become increasingly difficult. The last man to do the job had been using the role as an opportunity to sober up. But a friend arrived with a box of alcohol, and heavy drinking ensued. It ended in the host trying to shoot his guest for tempting him to fall.

The island had been Natalía’s first experience of living in Iceland full time. Apparently, it was not uncommon for foreigners, and even Icelanders, to come to Iceland only in summer to do ‘summer jobs’. Staying year round was a different act requiring a particular mentality, and it was an expression of commitment understood by everyone who did it. She learned Icelandic from Salvar and from watching television. And, thinking she would need to diversify her skills to live in this region, she taught herself first how to use a computer, and then how to do graphic design on it. Their arrival had coincided with the beginnings of the internet becoming mainstream. The world was now at her fingertips, and one thing they had a lot of was time. That is how they lived for those seven winters until moving to Ísafjörður.

I had been put in touch with Natalía and Salvar by my friend Hugh, a volcanologist. Every summer he travels from Lancaster University to the highlands of Iceland to study obsidian, a black volcanic glass found only in a few places in the world. A place called Landmannalaugar is one of his field sites. Hugh is the kind of person that, when you are round at his for a cup of tea, will place a lump of obsidian in your hand and enthuse about his latest discoveries. He told me that it is called hrafntinna in Icelandic: ‘raven-flint’. It has the dark lustre of a raven’s feathers and is superficially similar to flint in appearance, although flint is not found in Iceland. Specifically, Hugh studies how obsidian is made by breaking and then healing again, breaking and healing – in cycles. He is captivated by how its apparently perfect sheen ‘hides a history of repeated failure and recombination’. It is this history that makes it so strong and sharp – one of the earliest materials to be traded by humans, invaluable for tool-making.

Hugh met Natalía and Salvar at Landmannalaugar, where their provisions shop is the only one within a 60-kilometre radius. He uses the campsite as base camp and the shop is a godsend. Landmannalaugar is in a national park. There is barely any infrastructure, but every summer visitors descend in their thousands as it is the beginning, or end, of a famous hiking route: the Laugavegur (‘Way of Pools’). The eponymous laugar are hot springs around which this campsite has established itself over the years, and Salvar and Natalía’s business has expanded to meet the demand. Hugh is one of those rare creatures – a regular visitor with a deeply informed relationship with the landscape. He has a perspective on it that Natalía and Salvar could not have no matter how much they walked in it or lived in it. They, in turn, have local knowledge that has enriched Hugh’s understanding of the country and the place. Each summer had seen the continuation of an ongoing conversation, and they had become friends. It was a fortuitous coincidence that my conference was taking place in this town that Natalía and Salvar called home in winter, as most international events took place in the capital, Reykjavík.

One night they told me the story of their mountain shop. It began in 1996 when they were still art students in Hanover. That summer, Salvar brought Natalía over to Iceland to show her the landscape and to earn some money fishing. The local municipality had recently issued permission for local residents – mostly farmers – to fish as much as they wanted in several mountain lakes near to the Landmannalaugar campsite – then still only a small gathering of tents. Some short-sighted thinking had seen Arctic char introduced to the lake with no competing species. They had grown large for several decades, but eventually they over reproduced resulting in an excess of smaller fish. The char population needed reducing quickly. For several years following, Salvar’s brother Sveinn and his family had been net-fishing the smaller fish and selling it to tourists irregularly – tent to tent, or to order. When Natalía – the enterprising foreigner – arrived she organised the fishermen’s daily appearance at the campsite with their catch to supply the growing number of tourists.

In a highland desert the offer of fresh food was like a dream, and the fish were bought up willingly. Some tourists during that first season had asked if there was butter or oil to fry it with. Natalía and Salvar gave them some of their own. The next season, Natalía suggested, to Salvar and Sveinn’s bemusement, that they should sell butter and oil for more than they bought it for. The idea of making a profit was an alien concept to the brothers. Under Natalía’s guidance they broadened their provisions supply and within a few years they needed a vehicle from which to sell it. The first was an old army Hanomag truck. They would park it up on the campsite and tourists would come to them. Every season thereafter, their stock was added to according to tourists’ requests. Twelve years and several vehicles later, their enterprise has become a perfectly adapted organism – adapted both to the constraints of the location and to the needs of the people coming there. They showed me a photo of its current iteration: a mobile off-grid empire called Fjallafang – ‘Embrace of the Mountains’. Two green long-nosed vintage American school buses parked head to tail, painted with Arctic char dancing along the sides. One where customers could sit and drink their coffee out of the wind and rain, and the other filled to brimming with everything a hiker might need – and fresh fish.

I was taken by the idea of a business growing slowly and adapting to fill a niche, rather than moving in suddenly to occupy a space as many other businesses seem to do. Salvar and Natalía’s main objective seemed not to be to make a lot of money, but to provide a service and valuable information to visitors to this special place; to help protect it through their love of it. As tourism was on the increase now, they were enjoying the job less because they no longer had time to have real conversations with people.

The highland landscape is incredibly delicate, they told me. Salvar brought out astonishing photographs of its undulating bare mountains – ochre, purple, rust, teal and indigo, punctuated with opaque turquoise tarns and steaming hot springs, the tops pocketed with snow. It looked like the beginning of everything. They told me the ground was only exposed, largely free from snow, for three months a year – June, July and August. Any damage caused during summer by excessive footfall, the puncturing effect of walking poles, or off-road driving would be locked in and exacerbated by the elements for the nine months of winter.

There was barely any infrastructure in Landmannalaugar. Being in a national park, building was not permitted, although Salvar told me the main petrol company and convenience store chains were working hard to have the regulations changed. Before the Fjallafang fleet drove in each June, and after it departed each September, all that existed was a mountain hut and a shower block. A warden would stay on in the hut into the white expanse of October for the few Icelanders who came with their winter jeeps. ‘She loves that time of year, because she can step out of the hut in the morning and just scream,’ Salvar said, without comment.

Our long conversations, sat around the table in the ‘Winter Palace’, would sometimes continue until 2 a.m., when the sun had dipped just below the horizon and cast an outrageous pink all over the sky. The sea and sky were visible in a gap between houses, and I found them irresistible. As my hosts made their way to bed, I would head out onto the quiet empty street to meet the sea, to smell its sighing tidings, to listen to the murmurs of eiders and bask in the glow of the small hours. To have my private moments with this time, this place, this light – and this fluttering in my stomach.

One morning, as I wolfed down some muesli in the kitchen and exchanged a few words with Salvar over coffee, the fridge shook momentarily. Salvar lifted a finger and froze as if waiting for something.

‘Earthquake,’ he said.

‘Do I need to worry?’

‘Nei, nei. The Westfjords is not a very active region. That must’ve been quite far away, in the south country maybe. I’d better call my mother.’

The shudder had been so brief and Salvar’s reaction so relaxed that I continued with my day. This was not how I would have imagined my first experience of an earthquake.

The conference became an afterthought; a place I would go to during the day to sit in a dark room. I listened to PowerPoint presentations and watched ethnographic films about other places in the world. But, increasingly, Here beckoned much more strongly. And when it did, I would go outside. I wandered the backstreets of the town, enjoying the abundance of dandelions in people’s gardens and on the verges and the roundabout. They seemed not to be considered weeds. A smattering of bright colour after a long spell of whatever it is that winter looks like up here was probably quite welcome. There were tents up in most of the tiny gardens, which had low picket fences. I was excited by a culture that wanted to sleep outside as soon as the weather was good.

The sun seemed closer to the Earth here. It was much hotter than I had come prepared for, but still I wanted to buy an Icelandic jumper. Fortunately, in a small hand-knitters’ co-operative run by women, I found out that there was such a thing as a summer jumper: a thinner knit and sleeveless. I pulled one I liked from a pile on a shelf. ‘What size is this?’ I asked the woman at the counter. ‘Why don’t you try it on?’ was her excellent reply. I liked these people. The jumper fitted as if it were made for me, and I bought it.

Natalía and Salvar took time off from their summer preparations to take me to a swimming pool in a neighbouring fjord. ‘We’ve seen how much you like to look at things and take pictures,’ said Natalía as I climbed into their car. ‘So we’ve cleaned the windows.’ Ironically, to get to the pool we spent much of the journey inside a mountain. We drove through its single-track tunnel, which had a junction in the middle, my first encounter with Icelandic road planning.

‘Why is it single track?’ I asked.

‘It was a lot of work digging through bedrock in the 1990s,’ Salvar answered. ‘It saved money. But happily they accidentally dug into a new water supply – an underground waterfall, which is what serves the town now.’

Interspersed along the tunnel were several lay-bys marked by a blue road sign with the letter M. Salvar told me it stands for mætingarstaður – ‘meeting place’. A meeting place, not a passing place. Somewhere you’d take the opportunity to catch up with a friend or relative coming from the next fjord who you might not have seen for a while. Even a tunnel can be convivial.

We arrived in the village of Suðureyri and pulled up outside the only tall building. A mural spanned the end wall and Natalía and Salvar told me it was their handiwork, a renovation of an old work by a local artist. Between them, they seemed to be the public art people. The building turned out to be the school and the outdoor pool was attached to it. Natalía and I entered the women’s changing room.

‘Shower first, naked,’ she told me.

On the wall was a poster: a map of the human body, showing me where my dirty parts were, in case I was unsure. One button turned on all 8 showers. It seemed rather wasteful.

‘It’s spring water… plenty of it,’ said Natalía from under the steaming flow.

‘Geothermal?’

‘Yes.’

I wasn’t used to guilt-free abundance. The shower was powerful and hot. I lingered there long after Natalía had gone outside and the shower alone would have left me satisfied. But I stepped out to a crystal-clear swimming pool, no smell of chlorine. A mountain rose directly behind the fence. Better still, the pool was flanked by three hot tubs of varying temperatures. I joined Natalía and Salvar in the hottest one and we floated in silence, letting the sun onto our bodies and the heat into our joints. Behind my ears the pool’s overflow gurgled. The other side of the fence a cascade of water trailed down the steep mountainside; a white noise finding a route through the scree. I turned on my front and noticed a flask of coffee.

‘Do we have to pay…’

‘Help yourself,’ said Salvar.

Free coffee. In a hot tub. Spring-fed. On a mountainside. I wondered at how life could be this blissful. I wondered if there was a catch, and what it was, but then soon forgot I was wondering.

‘I love that everyone is camping in their gardens at the moment,’ I said, finally breaking the silence.

‘Camping?’

‘Yeah. I was walking around Ísafjörður and there’s tents in almost every garden.’

‘That’s because of the earthquake. In case it’s just the beginning of something. It’s not safe to stay in your house if there’s a stronger one.’

I felt stupid. ‘Where was the epicentre?’

‘In the south country near to my mother.’

‘Is she alright?’

‘Her house is fine but the road to it has a large crack in it now.’

Perhaps that was the catch – the knowledge that the ground beneath your feet is shifting all the time; that the only thing you can know is what is happening now. Is that a catch?

My memories of that week, spent shifting between the films inside the conference and the constantly surprising reality outside, are a series of hyper-real luminescent images. They cut between close-ups of lichen-scribbled rock and the urgent shoot-growth of many species of tiny plants I had never seen, long shots of walking through broad vistas of a seemingly newborn landscape that felt all mine, and mid-shots of faces engaged in conversation. The conference is a series of fade-to-blacks where sleep should have been, but often was not.

Rising above all the other plants in late May were the umbrella-like fronds of wild rhubarb – large, waxy, dark green leaves atop stout pink stems. It was everywhere: on the hillsides between residential streets; out in the valleys. It was as if it had broken out of a garden one day and decided to take up residence somewhere freer. I decided to pick some and make a rhubarb crumble for Natalía and Salvar. I did this the next bright evening, after another day in a darkened room. They let me loose in their kitchen and we ate it after dinner, the sour-sweet flavour titillating our tongues for the evening’s long conversation. That particular evening, it was to be life-changing.

Natalía stretched her arms above her head, cat-like, and let out a moan of pleasure as seemed to be her after-dinner gesture. ‘Sarah,’ she said, as if it was a question. ‘We’ve noticed how well you managed a strange kitchen; making this… how do you say… krrrömbel.’

‘Would you like to run Fjallafang next summer?’ Salvar interjected. ‘We’ve been doing it for twelve summers and we need a break.’

‘Yes,’ I replied without so much as a second of hesitation.

I am not sure why so little rational processing went on in that moment, other than I felt that exactly what I had been seeking, but had not yet known the specifics of, was being offered to me on a plate: space. An absence of abstraction. A self-willed landscape. An antidote to the academic London life I had been living. Just me, the mountains and a load of people passing through. As they came and went, I would be staying. Watching the weather change, the meltwater course, the light remain – day and night – until the darkening of August.

‘Yes. I really would,’ I said almost to myself, sensing I was accepting an invitation to something much greater than a summer job.