Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The Hamble rises at Bishop's Waltham in Hampshire and flows into Southampton Water. It is a relatively small river but it has an interesting and varied history. Above Botley, the Hamble powered a number of mills, and in the 17th century plans to make that section navigable were contemplated. The tidal river below Botley has served as an important local conduit for the carriage of goods and commodities, particularly timber, underwood and flour, and a number of industries, including fishing and salt production, have flourished on its banks over the centuries. King Henry V's fleet was stationed on the river and in the 18th and 19th centuries it was an important location for naval shipbuilding, not least because of the ample supplies of timber to be found in the valley. One of Nelson's flagships, HMS Elephant, was built there in the 1800s. The proximity of Southampton and Portsmouth meant the river was militarily important during the Second World War as well as in earlier conflicts. It also boasts a number of literary associations, particularly that of William Cobbett, who lived and farmed at Botley for a number of years at the beginning of the 19th century. The river has been a popular centre for yachting for over 100 years and there are a number of boatyards and marinas along its lower reaches today. However, despite this and other commercial development, the river is still prized for its natural beauty, and large sections are protected for their ecological and conservation value. Drawing on printed and archival sources, and with a wealth of illustrations, this book traces the river from its source to the sea.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 182

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

View of the Hamble from Fosters Coppice.

CONTENTS

Title

List of Illustrations

Illustration Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

The Valley

PART ONE: THE BISHOP’S RIVER – BISHOP’S WALTHAMTO BOTLEY

Around the Source

The Valley of the Mills

The Phantom Navigation

PART TWO: AN ARMOFTHE SEA – BOTLEYTO BURSLEDON

Crossings

‘A River just about as wide as your Parlour!’

The Waterway

Woodlands

‘A River Almost Unique in Character’

PART THREE: THE BURSLEDON RIVER – BURSLEDONTO HAMBLE

Origins and Archaeology

Bridges and Ferries

Shipbuilding

Other Industries: Fishing, Saltmaking, Ironworking and Brickmaking

The Haven

Twentieth-Century River

Select Bibliography

Copyright

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

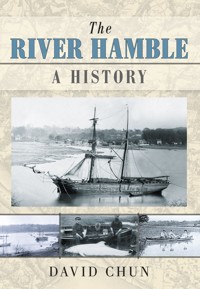

Frontispiece - View of the Hamble from Fosters Coppice

1.One-inch Ordnance Survey map showing the whole length of valley

2.Estuary from west bank of river above Bursledon

3.The Curbridge ‘whale’

4.River scene at Curbridge in the early 19th century

5.View of the Hamble from Elm Lodge at Bursledon in the 1890s

6.Hamble River frozen over

7.Pencil drawing of vessel on the estuary, c.1830

8.Extracts from six-inch Ordnance Survey map of 1868 showing the section of the valley from Bishop’s Waltham to Botley

9.Park Lug: 20th-century photograph

10.A 1784 engraving of Bishop’s Waltham Palace and pond

11.Ford south of Locks Farm, near Bishop’s Waltham

12.Steam train on Botley-Bishop’s Waltham branch line in 1898

13.Frenchman’s Bridge

14.Botley Mill, pre-1960

15.Mill Hill, Botley, looking east, c.1908

16.Part of Botley Mill, in an 18th-century drawing/elevation

17.Durley Mill, c.1908

18.Upstream view of Durley Mill

19.The Hamble above Botley, c.1900, showing Railway Viaduct

20.George Morley, Bishop of Winchester

21.Extract from six-inch Ordnance Survey map of 1868 showing the section of the valley from Botley to Bursledon

22.Botley Bridge and a lighter on the river, in a 19th-century drawing

23.Botley Square from a early 19th-century engraving

24.Wooden bridge at Botley, in a 19th-century drawing

25.Botley House and the bridge over the Hamble, in a 19th-century engraving

26.Portrait of William Cobbett

27.Estates of William Cobbett as shown on a map dated February 1813

28.Bridge over Hamble linking Hill House and kitchen garden

29.Granary of Fairthorn Grange, 1946

30.The Boathouse at Botley Quay

31.The Bark Store and Quay

32.An 1840 sale advertisement for House and storehouse at Bursledon

33.Photograph of Bell’s coal yard on wharf at Botley

34.Low-level aerial photograph showing river at Pinkmead

35.Survey drawing of Eyersdown Hard site

36.Plan of timber yard at Pinkmead, c.1800

37.Drawing of Blue Anchor public house

38.Photograph of Pinkmead Cottages & River, Botley

39.Vessel called Scotsman at Bursledon in 1890s

40.View of the valley from Vicarage Garden, Bursledon, 1887

41.View of Hamble from Fosters Coppice

42.Tree fellers on water side. Charcoal drawing, c.1830

43.Advertisement offering timber for sale at Durley

44.Woodland scene in the 19th century at Freehills between Bursledon and Botley on the west bank of the Hamble

45.Half-finished sketch of river looking south-west from the mouth of Curbridge Creek, c.1830

46.Hugh Hobhouse Jenkyns (1880-1947)

47.River Hamble, near Curbridge, c.1900

48.Extract from six-inch Ordnance Survey map of 1868 showing the section of the valley from Bursledon to river’s mouth at Hamble

49.Prehistoric hand-axes

50.Late fourth-century A.D. leaden ‘curse tablet’ found on foreshore of Hamble estuary in 1982

51.A logboat found on the Fairthorn estate in 1888

52.The medieval bridge at Curbridge, in a 19th-century sketch

53.Extract from 17th-century map of valley showing Bursledon Ferry

54.Early 18th-century map of roads leading to Bursledon Bridge

55.Engraving of bridge on share certificate issued by Bursledon Bridge Company

56.Old bridge, with ice on the river, probably taken during the harsh winter of 1894/5

57.New bridge at Bursledon, built in 1930s, with the railway bridge beyond

58.View of Bursledon, including church and waterfront

59.Extract from Lieutenant Murdoch Mackenzie’s 1783 Survey of Southampton River

60.Wall tablet erected in memory of Philemon Ewer in St Leonard’s church at Bursledon

61.Survey drawing of shipbuilding site at Bursledon Point

62.Wall tablet in memory of George Parson in St Leonard’s church at Bursledon

63.Photograph of men sitting on ‘carbs’ on the Warsash foreshore

64.John Doswell’s map of Southampton and district in 1802

65.Map of part of Parish of Hound map showing ‘Mr. Gringo’s Furnice’ in the 1720s

66.Hoe Moor or brick kiln creek – pencil drawing from 1830s

67.Waterfront at Bursledon in the 1890s

68.Extract from 17th-century map of valley showing lower part of Hamble estuary

69.Hamble by G.F. Prosser, 1845

70.Bursledon waterside

71.Lower estuary in late 19th century

72.Hamble, taken before the Second World War during which the foreshore was built up with rubble from air raids

73.Lower estuary in the early 20th century

74.‘Porpoise’, measuring 8 feet in length, caught on upper part of tidal Hamble

75.Upper reaches of Hamble estuary

IILLUSTRATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSIllustration numbers in bold.

Anne Hayward / 93; Author’s Collection / 26, 43, 90, 91; Bartolozzi (engraving after 1800 portrait by John Raphael Smith) / 29; Botley & Curdridge Local History Society / 5, 17, 21, 22, 34, 35, 38, 92, BCLHS77 / 54, BCLHS CPIC 0078 / 20, BCLHS PH019 / 18, BCLHS PH073 / 31, BCLHS PH128 / 39, Courtesy of Dennis Stokes / 88; Francis Grose, The Antiquities of England and Wales / 13; Hampshire Record Office / 2, 11, 24, 55, 5M53/1128/4e / 19, 29M67-13 / 37, 41M89/151 / 41, 44M73/E/P68 / 30, 45M69/133 / 62, 52M48/13 / 63, 58A01/1 / 7, 58A01/1 / 8, 58A01/1 / 45, 58A01/1 / 65, 58A01/1 / 84, 58A01/2/1 / 50, 58A01/2/2 / 46, 65M89/264/3 / 32, 65M89/Z42/30 / 66, 93M94/33 / 49, 103M96/12 / 87, 120M94W/E27 / 86, 130M83/PZ13 / 6, 130M83/PZ13 / 9, 130M83/PZ13 / 25, 130M83/PZ13 / 27, 130M83/PZ13 / 42, 130M83/PZ13 / 48, 130M83/PZ13 / 51, 130M83/ PZ13 / 60, 130M83-PZ13 / 67, 130M83/PZ13 / 82, Photocopy 641-2 / 81, TOP 037/2/2 / 28, TOP Portraits M/10 / 23; Hampshire & Wight Trust for Maritime Archaeology (HWTMA) / 40, 77; H.C. Oakley, 1889 Hampshire Field Club Proceedings / 59, 1894 Volume / 61, 85; Roger Pearce / 4, 47; Southampton City Library / 71; Westbury Manor Museum/Fareham / 56, 58; Bryan Woodford / 79; Reproduced by kind permission of Mrs Nichola Gottelier / 52.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A book, even a modest one such as this, creates debts for the author. The material on which it is based has been gathered during the period of over twenty years that I have lived in the Hamble valley. The late John Hogg of the Botley and Curdridge History Society was one of the first people I met who shared my interest in the Hamble river. I still remember with gratitude his many kindnesses to me in providing information and encouragement. I have used some of his research in the chapter on the river trade, and like to think that he would have approved of the use I have made of it. I am grateful to the Botley and Curdridge History Society for permission to reproduce a number of photographs in their collection. Dennis Stokes, a stalwart of that Society, has been particularly helpful in supplying copies of photographs and other information. He was also kind enough to read and comment on a draft of my text. Paul Donohue of the Hampshire and Wight Trust for Maritime Archaeology also read an early draft, and he and Julie Satchell of the Trust have been very helpful is supplying information. I am grateful to all of the many institutions that have permitted me to reproduce illustrations in their collections, and answered my queries. Sarah Lewin and Linda Champ of the Hampshire Record Office have been particularly helpful in this regard. They, and the other members of the Record Office staff, have been unfailingly helpful and courteous to me during the years I researched the material for this book. Tom de Wit of the Westbury Manor Museum in Fareham has also taken a great deal of trouble in providing photographs of items in the Museum. My friends Barbara Biddell and Kevan Bundell also read drafts of this book and made helpful comments and, in Barbara’s case, provided illustrations and information. I am also grateful to Bryan Woodford who kindly supplied a copy of an early photograph of the Warsash waterfront. Last, but not least, I must thank my family, Mandy, Philippa and William, who put up with my many absences in ‘The Outhouse’ working on this book.

INTRODUCTION

THE VALLEY

In terms of the almost dizzying lengths of geological time and process, the Hamble River flows through a relatively young landscape. It did not take on its present form until about 6,000 to 7,000 years ago when, in the last of a series of great inundations – the Flandrian transgression, the valley of the ancient Solent River was invaded by the sea. Southampton Water was created and the lower reaches of the Hamble, previously a tributary of the now drowned river, was given its present estuarine character. This was long after our prehistoric ancestors had first begun to frequent the Solent region.

The Hamble rises on the chalk formed in the Cretaceous Period (146 to 65 million years ago) but for much of its 12-mile length flows through a valley formed of Tertiary deposits – largely clays and sands – that were laid down in a great trough, or syncline, in the chalk (hence the term Hampshire Basin) during the Palaeogene Period, some 65 to 23 million years ago. Throughout this time the sea level periodically rose and fell. At times the sediment that was to form the clays and sands was laid down in a shallow sea, as evidenced by the sharks’ teeth and other marine fossils found at West End; at other times, when the sea was for a time excluded, these were formed in estuarine conditions or in fresh water.

London Clay, Bagshot Sands and Bracklesham Beds are the principal components of these Tertiary deposits that form the solid geology of much of the valley. Overlying these are the ‘drift’ deposits – the brick-earth, clay with flints and, most significantly, gravel. These later deposits are probably a legacy of the Ice Age (Pleistocene Epoch of the Quaternary Period), when, during three glacial phases, great sheets of ice covered much of the British Isles. Although these did not directly affect southern England, it would have been subjected to tundra conditions. Each spring large quantities of material would have been washed down braided (multi-channelled) rivers and, according to current thinking, this formed the coastal plateau that includes the land on both sides of the Hamble below a line represented roughly by that of the A27 road.

IFirst edition of one-inch Ordnance Survey showing the whole length of the valley from Bishop’s Waltham to Southampton Water.

The underlying geology and the resultant soils assist our understanding of the present-day valley, both the river and the landscape through which it flows. And, with the geology in mind, it is convenient to divide the valley into sections. It has been observed that the estuary of the Hamble is unusually long given the river’s overall length, and the section of the tidal river below Bursledon can be contrasted with that above the M27. The non-tidal river above Botley meanwhile has its own quite distinct character.

Below the Bursledon Bridge, which carries the A27 across the water, there is greater commercial and recreational activity than elsewhere on the river. But while there are marinas and pontoons, and, therefore, more boats than upriver, the areas of saltmarsh on the east bank – Lincegrove and Hackett’s Marshes – and prominent areas of woodland, such as Cawte’s and Downkiln Copses, still provide a sense of space, if not of wildness and relative isolation like the river above Bursledon. As the river is wider here, one is more conscious of the open sky. This section of the estuary flows through the previously described largely flat coastal plain. These terraces of gravel, a legacy of the Quaternary, provide well-drained and productive farmland used for arable production, market gardening and horticulture. Once the valley was a great strawberry-growing area, and the fruit grown here was prized for the ‘earliness’ of its cropping; with strawberries typically being picked two weeks earlier than in Kent. It also provided good building land: the ‘hoggin’ gravel provided secure foundations, and much land has been lost to development, particularly on the Warsash side of the river.

Above Bursledon, the valley has a quieter character. The river here flows through, in landscape terms, an older countryside. The field pattern is more irregular and there is a greater area of ancient woodland; it is a bocage terrain, the ‘clay and coppice’ countryside that Botley farmer William Cobbett favoured. The soils are heavier too, large areas being on the stiff London Clay, particularly on the eastern bank, with more land being given over to grazing, though there is still some arable production and horticulture. The riverside land is largely undeveloped and the ancient woodland in places runs down to the water’s edge; again there are pockets of salt-marsh and reed-beds. As we shall see, this section of the river has long since been prized for its natural beauty and, despite the hum of traffic along the M27, still has, in certain seasons and times of the day, a surprisingly unspoilt quality.

2Estuary from west bank of river above Bursledon.

Botley, where, as Cobbett noted, fresh water ‘falls’ into the salt water, marks the upper limit of the tidal river. The non-tidal river above Botley flows through a narrow valley largely given over to improved pasture and woodland. The historical function of this part of the river was to provide water power to drive the several corn mills (and one paper mill) that once existed between Botley and Bishop’s Waltham, just above which the river rises. This section of the river has suffered from water being taken for the public supply. As we shall see, by the last century there was insufficient flow of water to drive the mills, and in the dry summer of 2006 The Times reported that the river here had, temporarily at least, ceased to flow.

The main river is not the whole story, of course. More than thirty streams and rivulets, which drain the surrounding countryside, feed into it. The headwaters rise on the chalk, where there are numerous springs. The source of the river is taken as being at Northbrook, just to the north of Bishop’s Waltham, but soon it is augmented by another large stream that rises at The Moors, an area of wetland to the east of the town. This is the first of a series of large streams that flow into the main channel. Many of them include in their names the denominative ‘Lake’ – Ford Lake (the chisel-bourne or gravelly-stream of the Anglo-Saxon land charter for Durley of A.D. 900), Shawfords Lake and Pudbrook Lake. The term ‘lake’ apparently derives from the Old English for a small stream or watercourse, not the modern word ‘lake’ that comes from the French. However, to anyone who has seen one of these streams in full spate in winter, brimming over its banks after days of heavy rain, the latter sense seems entirely apt. This is another effect of the geology. There is rapid run-off from the Tertiary streams – the impermeable clays are unable to absorb heavy rainfall – and the sediment carried down by the streams re-charges the mud of the estuary.

3Photograph showing the Curbridge ‘whale’. It was found in Curbridge Creek on 2 August 1932 where it was seen by 5,000 people. At the time it was identified as beluga or white whale. Modern research, though, suggests that it was actually Risso’s Dolphin, Grampus griseus.

Man has had a presence in this valley for many hundreds of thousands of years. The first people to frequent it would have led a nomadic existence, sustaining themselves by hunting and fishing. Hand-axes, made from knapped flint, have been found at Warsash – indicating human presence in the valley in the Lower Palaeolithic, hundreds of thousands of years ago, long before rising sea levels caused the lower estuary to take on its present form and when Britain was still connected to mainland Europe. Other evidence of man’s early activities in the valley is scattered all along its length. There have been discovered, in gravel workings at Fleetend and Hook, close to Warsash, field systems and other evidence of continuous occupation from the Bronze Age into the medieval period. A Bronze-Age burial pit was discovered at the brickworks at Swanwick in 1927 and the earthworks of an Iron-Age fort can still be seen on Hamble Common. The Roman occupation is represented by a villa complex, which has been partially excavated at Fairthorn, at the confluence of the Hamble with Curbridge Creek, close to the Roman road that crossed the river at this point.

4River scene at Curbridge in the early 19th century.

In the Anglo-Saxon period the river has a more tangible presence: by then it has a name. The Venerable Bede, writing in A History of the English Church and People of about A.D. 731, describes the River Homelea as entering ‘the sea after flowing through lands of the Jutes who lived in the Gewissae country …’ The name, unlike that of other Hampshire rivers, appears to have a Germanic origin, indicating that it was bestowed by the Anglo-Saxon migrants who arrived in southern England after the collapse of the Roman Empire. The name means ‘maimed’ or ‘crooked’, which almost certainly alludes to the river’s winding course and, in particular, the great bend at Bursledon. Interestingly, there is a river called Hammel in Germany, a tributary of the Weser.

With the compilation of Domesday Book in 1086 we can start to fill in some of the blank spaces of the river’s hinterland. It records settlements at Hound, Netley, Botley and Bishop’s Waltham and several on the coastal plain to the east of the river, including Titchfield, Hook and Brownwich. The presence of three pre-Conquest -ley place-names, those of Durley, Botley and Netley, which means an inhabited clearing in woodland, suggests that parts of the valley were well-wooded in the Anglo-Saxon period. Domesday Book, for this part of Hampshire, is not as helpful as it might have been in recording woodland cover. Not only is it a swine-rent county, where woodlands are recorded by the number of swine they could sustain rather than by area, which makes the extent of woodland hard to quantify, but some of the entries for woodland are confusing. Whereas Netley is shown as having woodland for 40 swine, a relatively large number, the entry for Botley records that there is no woodland; this hardly tallies with the records of extensive woodland in later centuries, or indeed with the extent of ancient woodland that survives today. The explanation may be that the woodland belonged to the King, being part of the Forest of Bere, which stretched westwards to Southampton, and thus not taxable in the hands of his subjects.

Hamble, Warsash and Bursledon, though not mentioned in Domesday Book, were medieval settlements. By the early Middle Ages the pattern of village, farmland, woodland and heathland was established, and probably did not alter greatly until the great heaths of the district – such as Botley Common (enclosed in about 1815), Titchfield and Swanwick Commons (enclosed in about 1859) – and much woodland was destroyed in the 19th century. More farmland and further woodland has been lost to development in the last century. A reminder of the heathland is provided by the sometimes extensive patches of gorse and broom that can still be seen on the sides of the motorway and in other odd corners.

5View of the Hamble from Elm Lodge at Bursledon in the 1890s.