8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

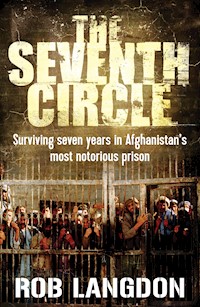

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

A harrowing account of Afghanistan's notorious Pul-e-Charkhi prison, written by its longest-serving western inmate. Former soldier Rob Langdon was working as a security contractor in Afghanistan when he was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death in a case that would have been ruled a clear miscarriage of justice in the British legal system. His sentence was commuted to 20 years in jail, and he served his time in Kabul's most notorious prison, Pul-e-Charkhi, described as the world's worst place to be a westerner. Rob was there for seven years, the longest sentence served by a westerner since the fall of the Taliban, and every one of those 2,500 days was an act of extraordinary survival in a jail filled with Afghanistan's most dangerous extremists and murderers. In 2016 Robert was pardoned and returned to Australia. In this highly-anticipated book he will talk about his experiences for the first time.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Contents

List of Illustrations

Author’s note

PART ONE DEAD MEN

1 The arrest

2 What I’d done

3 On remand

4 Left for dead

5 Enemies within

PART TWO THE SEVENTH CIRCLE OF HELL

6 Punishment

7 Why I was there

8 Dead man walking

9 Little Africa

10 Life after death

11 Saving lives

PART THREE SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST

12 Mates

13 The beacon

PART FOUR STRANGE FRIENDS

14 Last man standing

15 The Taliban and I

16 A soldier in prison

17 Seven years

18 Surviving

Epilogue

Picture Section

Copyright

List of Illustrations

4 Section, 9 Platoon, C Company, 1RAR in Timor Leste, January 2001.

Team Leader with Edinburgh International on Operation Artemis, Baghdad, 2005. Shortly after the first Iraqi elections.

Preparing for an airport run along the notorious Route ‘Irish’ outside Baghdad’s Green Zone, Operation Artemis, 2005.

Near Gardez, Afghanistan, in 2009, with SD (left) and Frank (centre). On the way to get ‘Rosie’, the three-year-old girl who had been burnt. (Photo Marcus Wilson)

Two of the good guys in Afghanistan, medics KC (left) and Marcus (right).

The opportunity to do good came up all too rarely. ‘Rosie’, a three-year-old girl, had been burnt by her family to get money from the Americans. Marcus, Frank and I helped get her on a helicopter to a proper hospital. (Photo Credit Marcus Wilson)

Top of the Garden Range, 2009. All the provinces had the gates built on the roads leading in.

Watching a convoy in the ‘Green Belt’ near Salar—the local word for ‘rifle’.

My personal kit. Because the company was not spending money as it was meant to, I had to buy most of it myself.

Pol-e-Charkhi as I never saw it, from the outside. The outside fences were superfluous: as you can see, there was nowhere to run. (Photo Steve Kenny)

In Block 4, the corridor outside the living area was covered in graffiti and burn marks—the aftermath of the earlier riots in 2005, long before I got there.

This is not the aftermath of a riot—it’s how the other half lived. One of the Afghan prisoners’ living areas in Block 4. (Getty Images/Mario Tama)

Hangings in Pol-e-Charkhi were messy. When the condemned men hung from this gallow, their feet often touched the ground and they strangled slowly. (Getty Images/Wakil Kohsar/AFP)

The nooses. All those chairs are set up for politicians and dignitaries to watch the hangings. (Getty Images/Nur Photo)

The ‘gym’ where we worked out in the Nigerian–Ugandan living area, Block 4. The equipment was all homemade.

A communal meal with the Africans, Block 4, 2010.

Kettle bells and dumbbells made by pouring stolen cement into empty drink containers.

A day’s food for five people: Block 4, 2011.

The western view from Block 4, winter 2011. Even with the thickness of the walls and the small windows, the winter cold was severe.

A makeshift volleyball court, Pol-e-Charkhi. I never saw this. (Getty Images/Massoud Hossaini)

View to the north, winter 2011. The large tower is a water pressure tank, not a guard tower.

In Block 4, the Africans made home brew by fermenting anything from tomatoes to apricots. Funnily, the master brewer was Abdelrahman, a practising Muslim who didn’t drink.

Visiting day, Block 4, 2011. Some of those tents were set up for prisoners to enjoy some intimacy with their visiting wives.

My sleeping space inside Block 4. Not luxurious, but bearable.

A product of my environment, Block 4, 2012.

The Afghan National Police’s own crop: they grew marijuana outside Block 10 and sold it to the prisoners.

The police’s weed harvest, Block 10, 2016.

Adelaide lawyer Steve Kenny looked after the Australian end and visited Pol-e-Charkhi in 2011. (Photo Nathan Amy)

Shitty the cat on one of her favourite perches, 2015. I wouldn’t be surprised if she’s running the prison by now.

The beacon: once Kim Motley got involved with my case, I was headed for freedom. This is on 31 July 2016. I am waiting to sign release papers. An hour earlier, I was in my cell. (Photo Jessica Donati)

Out! Chatting with Kim, 31 July 2016. And a lot of Afghan officials looking for the opportunity to show the world what good people they are. (Photo Greg Pye)

In the days immediately after my release, I stayed in Kabul to decompress—and did some close protection work for Kim. (Photo Joel Van Houdt)

With Kim at Kabul Airport, waiting to leave. The same place I’d been so close to getting out of seven years earlier. (Photo Joel Van Houdt)

Author’s note

Where friends or colleagues remain operational, I’ve used their initials in order to protect their identities. Other names have been changed to protect the guilty. You know who you are.

PART ONE

PART ONE

Dead Men

2009–2010

1

The arrest

Here’s how close I was to getting away.

Minutes. Maybe five, maybe three, stood between me and getting on the plane. I had got to Kabul International Airport and walked through check-in without luggage or any possessions other than the clothes on my back and the packages of American dollars in my pockets. I was cleared through customs and several security gates in the clean, newly built terminal. My flight on Afghanistan’s national carrier, Safi Airways, to Dubai was on time, and I made it through the departure lounge where I showed my boarding pass and waited with the other passengers for the minibus to take us to the plane sitting on the tarmac. All that was left was a quick shuttle to the steps of the jet and I was home free.

Just a few hundred seconds. As long as a cupful of water takes to boil. How many times, over the next seven years, could I shut my eyes and count out those seconds? How many prison kettles of water would that add up to? In what kind of a blink could they pass, compared with the black hole that would chew the next seven years out of my life? If I thought about that too much, I could drive myself mad.

I kept my head down, not looking at the other passengers, just willing the minibus to come and take us to the plane. After the chaos of the previous twenty-four hours, I was more strung-out with fatigue than panicky or scared. I was composed but tired, thinking only one thought: Let’s go. I wore my Blundstones and a checked shirt and jeans that I’d picked up earlier in the day from my mate Frank, whose place I’d dropped into during the height of the mayhem. Frank, a Canadian freelance security contractor I’d worked with for years in Afghanistan and Iraq, and I had talked about which airport I should go to. One option was the airfield at Bagram, the military base where I could get onto an American military aircraft. Bagram had its advantages, being under American control, and as a security contractor working for an American company, I had come and gone freely from Bagram over the previous twelve months with identification that gave me the equivalent rank to a captain. Frank made a plan to get me there. But I was wary of Bagram. The drive was too far for comfort, and the security would be intense. Any of numerous checkpoints could pull me up. My preference was for Kabul International, the civilian airport. I had bought the Safi Airways ticket for Dubai the previous day, before all hell broke loose. A day ago, I had expected to be flying out of Afghanistan for the last time on my way to starting a new adventure in Africa. It might as well have been a lifetime ago. In twenty-four hours, everything had changed.

Bagram or Kabul International? US military or Afghan civilian? In the end, I did what I always did when faced with a fifty-fifty decision. I pulled my trusty Australian fifty-cent coin out of my pocket and tossed it.

Heads. Kabul International.

Frank wished me luck as I left his place in a taxi. I got to the airport without incident. Like a lot of major infrastructure in the city, Kabul International was fitted out with the latest computerised equipment, but the locals didn’t know how to use or maintain half of it. It looked nice, but everywhere you looked were half-finished offices, rubbish blowing around, and computers still in their boxes. The grand opening for international civilian flights, just a few weeks earlier, was the first step in the airport’s decline to wrack and ruin.

The security arrangements were tight, though. A British company called Global Risk Management, which employed several people I knew in the tight-knit world of private security contractors, had been teaching the Afghans how to do airport security, and they were efficient. I was inspected, scanned and searched at two gates after passport control. I went down a set of stairs to the departure lounge, and as I was waiting for the call to board, my phone rang. The screen said it was Anton, one of the managers at work.

‘It’s all good,’ Anton said. ‘Just wait there, you’ll be fine.’

I trusted Anton, in as much as I could trust anyone who’d done the things I’d seen him involved with. Actually, I didn’t really know how much I could trust him. I was working that out as I went along.

Soon enough I had an answer. Another call came in. It was Elena, who worked as an administrator at Four Horsemen, the American company I had worked for in the year since I’d been in Afghanistan. Elena was the wife of Petar, the operations manager and leader of a group of Macedonians who held senior positions in Four Horsemen’s Kabul office. Elena was really good at her job and we’d had a cordial professional relationship during my year in Afghanistan. I treat people as I find them, but the Macedonians didn’t like other men talking to their women, and my friendliness with Elena had never gone down very well with her husband and his mates.

‘Rob, I have to warn you,’ Elena said.

My heart rate went up a little. ‘What’s going on?’

‘My husband has given the NDS passport photos of you, details about you, everything they need to identify you. They’re coming for you now. You need to get out of the airport.’

Fuck. Had I been sold out? The NDS, or National Directorate of Security, Afghanistan’s secret police, had close connections to Commander Haussedin, the local war lord who I believed was the main source of all of my, and our company’s, problems. If Petar had sold me out to Haussedin, the next few minutes could be the difference literally between life and death. I considered my options. I couldn’t go back out of the airport the way I’d come in: on the streets, I would never escape. I couldn’t get to Bagram now that the alert was out. And my Safi Airways flight was only minutes from boarding. My way out of here was in that plane.

Over the next seven years, I thought about Elena’s call. As I gathered more information, I eventually came to reconsider what had happened. Maybe I wasn’t really seconds from getting away. Maybe it was all a set-up. Maybe that minibus would have just waited on the tarmac for however long it took for the cops to come and grab me. Maybe, as I wished for those few seconds to tick over, my fate had already been sealed by forces beyond my knowledge or control. In a strange way, that consoled me. Better to be angry at betrayal than wringing your hands over bad luck and a couple of minutes.

In the events that followed Elena’s call, I had one—if only one—stroke of fortune. The eight men who came into the departure lounge to grab me, led by an officer waving around a copy of my passport photo page, my company ID and some other proof-of-life documents, were wearing uniforms. They were Afghan police, not NDS, who would have been in plain clothes. If the NDS had arrested me I would probably have been taken to a ‘black’ or secret prison, tortured and murdered. I’m reasonably sure that that’s what would have happened if I had tried to get into Bagram.

The uniformed cops didn’t tell me I was under arrest. They didn’t tell me anything. Without a single word, they grabbed me by the arms and marched me back through the departure lounge. I played dumb. As we walked, I got my hand into my pocket and found the redial button on my phone. The last person I’d called was Frank, and I definitely trusted him. With my phone on and the redial button pressed, I hoped that Frank could hear what the police were telling me as they walked me through the airport. Frank would put two and two together and know I’d been caught. The most important thing was to remain visible.

As we walked, I began asking loud questions, spelling everything out so that Frank could overhear exactly what was going on.

‘What are you doing?’

‘Where are you taking me?’

‘To police headquarters or the commander’s office here?’

‘Why are there eight of you who need to do that?’

When we came towards the airport security office, I had one last hope: the ‘Green Line Handshake’, as it was called. On the frequent previous occasions when I’d had to go through Kabul International Airport, a security officer I knew, Captain Hamid, would help me and other security contractors avoid certain levels of scrutiny. Four Horsemen would send us to Dubai with as much as two or three hundred thousand American dollars in cash that it wanted us to hand over to Tim Akuchi, the company’s Kenyan-born financial controller. For the company, it was worth spending a few grand in bribes and airfares to get hundreds of thousands out from under the tax man’s nose. So we contractors would be given a return flight to Dubai, five grand to piss away while we were there, and a couple of grand for Captain Hamid and his Green Line Handshake.

I had US$12,000 on my body: $10,000 I had collected that day, in the rush to leave, from my own bank account, which I’d stashed in my pocket and in my ID holder, plus another $2000 in cash that I always carried in my wallet for emergencies. This might be my last chance. I thought my luck might be turning when Captain Hamid appeared among the uniformed men gathering outside the airport security office. My last resort was to get a private moment with him. There might be some way he could take some money and escort me back to the plane. I tried to catch his eye.

When we entered the office, that hope fell away. Sitting by the desk was Commander Haussedin. I thought, I know where this is coming from now. Of course. Captain Hamid was one of Haussedin’s men, a fellow Panjshiri tribesman. From the Panjshir Valley north of Kabul, this small but influential tribe were key players in Afghan politics, and whichever power was in charge, be it the Americans, the Russians, the Afghan Taliban, the mujahideen or the mob of crooks installed after the American invasion, the Panjshiris always ended up on the right side of the deal. Everything dodgy, dirty and corrupt that our company did was ultimately connected to Haussedin and his Panjshiri cronies. It’s a mark of my desperation that I ever entertained the thought that Captain Hamid might have been able to help me.

Haussedin—who had turned into my nemesis and enemy over the previous twelve months—was not looking particularly happy as he sat in the airport security office and watched the uniformed police go about their business. They searched me in front of the war lord and took my wallet, my passport and other ID, and the $US12,000. They pilfered my sunglasses, pretty much helping themselves to everything but my clothes. I never saw any of it again.

Haussedin became furious when they found my phone, which was still on the line to Frank. They switched it off and trousered it. Haussedin began barking at the cops. Although I couldn’t understand what he was saying—throughout, they spoke only in Dari Persian—I gathered that he was unhappy that I had been taken by uniformed police rather than the NDS, and that somebody on the outside had been informed of my arrest.

Frank would, that day, call Four Horsemen to tell them where I was and what had happened to me. They said they already knew and told him to butt out of it. He had his hands full when the NDS turned up at his doorstep later, and he was forced to bullshit his way out of any suspected role in my attempted escape.

I was held in the airport security office for a couple of hours. Without an interpreter, I didn’t know what was going on. I knew what they had arrested me for, but had no idea what was going to happen next. As they talked among themselves, I acted meek and mild and dumb. Now and then I asked, in English, what was going on and if I could make a phone call, but that went nowhere.

With Commander Haussedin was a man the police described, in broken English, as a ‘legal representative’ from Four Horsemen. But he wasn’t a lawyer. My guess is he’d watched an episode of LA Law. He sat there obediently and did nothing other than watch.

Eventually he had some action to look at. Two plain-clothed police, who I understood to be NDS, came in. I thought, Here we go. I was handcuffed, thrown against the wall, searched again and photographed. The head of airport security hit me in the head, slapping me with an open hand, careful not to leave any visible damage. He was going off his brain, screaming at me, but what he was saying was surreal.

‘You’re a tourist!’

Whack.

‘You fucking tourist!’

Whack.

‘You’re a tourist!’

This was so bizarre, and so stressful, and I’d been awake for I don’t know how long, all I could do was start laughing. A tourist? That was what I’d done? I wasn’t too keen on tourists myself—pretenders, idiots who swanned into Afghanistan pretending to be hard men, wannabes, fake journalists, opportunists, drug-addled aid workers, the joint was crawling with tourists. And now I was accused of being one of them. I thought, Yeah, sure, man, I’m a tourist, just drop me at the nearest youth hostel.

By the time I came to understand what he was really calling me—‘You’re a terrorist!’—every policeman in the room had taken offence at my laughter and begun hooking in. One came up and hit me in the ribs with the butt end of his rifle, which he then used to crack the side of my jaw. I felt a tooth break off. I went down onto the floor, grabbing my head. They stopped for a moment and had a discussion. I think they agreed not to hit me in the face anymore, because from then it was open season on kicking me in the ribs, arms and legs. I tucked my head in while they all took turns. Credit to them, they stayed away from my face.

Once they were done, they frogmarched me out of the office into the public area of the airport. As we went down a flight of stairs, there were a couple of Americans coming up the other way, staring at me, What the fuck? written on their faces.

‘Yeah,’ I mumbled to them as I went past. ‘Bad day out for everybody, I think . . .’

The next hours blurred by. They threw me in a police van and took me to the headquarters of the counter-terrorism police in the centre of Kabul, where I was put into a cell. It was a shithole, filthy and damp and reeking of excrement, the worst you can imagine of a Middle Eastern jail cell. After a few hours, someone brought in a small bowl of rice. No water—I still hadn’t drunk a drop since I was at Frank’s place several hours earlier and was getting seriously dehydrated. I sat on the floor and bundled myself into a ball, my arms wrapped around my knees. I was so buggered I drifted into a half-sleep, but someone must have been on duty to make sure I didn’t get comfortable, because whenever I began to drop off some men would come in and give me another touch-up, handcuffing me to a wall so my arms were above my head and then slapping and kicking me.

They kept me there for a night. The next day they moved me somewhere else in the same building and left me alone for a day or so. On the third day they grabbed me roughly and threw me into another van, which took me to a holding cell packed full of what looked like criminal suspects dragged out of holes. Rail-thin and smelling like they hadn’t washed in years, these Afghans were sharing a bowl of rice like animals. They barely even noticed me. I went to a corner and tried to be invisible again. That cell was a concrete box with some thick glass tiles in a line above head height. Over the steel door was a security screen, shaped as a concertina, like a lift door, that the guards could look through. For a toilet there was only a bucket already full of shit that had overflowed onto the floor.

No doubt about it, I was fucked. The fact that I’d been given no proper lawyer, no chance to make a phone call, no contact with my employer let alone the Australian embassy or anyone who could speak English, all added up to the same thing. All bad. I was writing myself off. This is not looking good for you, champ.

2

What I’d done

I was arrested on a Thursday. On the Wednesday I had quit my job, killed a man and set his body on fire.

I am not a good man. I have a temper and do not suffer fools lightly. Ever since I was a boy growing up in the outback of South Australia, I have held firm beliefs about right and wrong and have been unafraid to stand up for myself when challenged. I was raised to do things as well as they can possibly be done and took my counsel from the books and the thoughts that accompanied me during long hours alone as a boy in the desert. My dad was a cattle station overseer and a wildlife artist, and we would spend hours in the bush, not saying anything, me asking and answering questions in my head about why things were the way they were and what I could do to make them better. Having grown up in such isolation, I had rigid ideas about how men should be. When I was a teenager, this sometimes got me into trouble. After I had been drawn into some fights and hauled up before a court in the remote South Australian town of Port Augusta, my mum told the magistrate that I was signing up for the Australian Army, which the magistrate accepted as a proper alternative to punishment by the law. During the fifteen years I then spent in the army, I guess I was known as someone who liked to do things his own way, was effective, and sometimes rubbed up against certain kinds of authority. I’d like to think that I was always dedicated to getting jobs done as well as possible, but others might have called me a maverick and a hothead. So be it.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!