Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

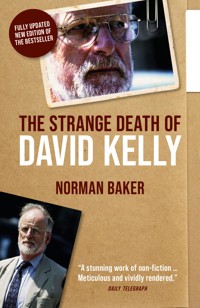

"Anyone can commit a murder, but it takes an artist to commit a suicide." – Old KGB saying The high-profile death of government weapons inspector Dr David Kelly twenty-one years ago, amid the tumult of Britain's controversial invasion of Iraq, plunged the New Labour government into crisis and led to the resignation of the BBC's director general. An informal inquiry chaired by Lord Hutton into the circumstances surrounding Kelly's death cleared the government of wrongdoing but was widely dismissed as a whitewash. The Strange Death of David Kelly argues that neither the medical evidence nor David Kelly's state of mind and personality supported the verdict of suicide. Analysing the official process instigated after Kelly's death, putting the entire episode into its political context and scrutinising the actions of the government in launching the Iraq War, this new edition of the instant bestseller is fully updated to include the latest evidence and theories surrounding this most mysterious and political of deaths.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 535

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

“A stunning work of non-fiction … Meticulous and vividly rendered.”

Daily Telegraph

“A superb summation of all the evidence.”

Sunday Times

“Norman Baker is an honest politician of unusual integrity. He is determined that British voters should know the truth about how we are governed. He asks difficult and problematic questions that seem not to have occurred to Lord Hutton. His research is very detailed and his conclusions must be taken seriously.”

Peter Oborne

“It may make uncomfortable reading for certain politicians and members of the intelligence community, but it is likely to persuade many that there was far more to the death of David Kelly than has been revealed.”

Evening Standard

Shortlisted for the Channel 4 Political Book Award 2008

iii

Contents

Introduction

The death of the weapons inspector Dr David Kelly in July 2003 shocked the nation. And when shock had subsided, anger set in. Britain had gone to war in Iraq on what most people regarded as, at best, dubious grounds. The weapons of mass destruction the Blair government had warned us about, deployable within 45 minutes, were nowhere to be found. And all through July, the government oozed spin like pus from a boil.

So when Dr Kelly, a patently decent and honest man, was found dead in the woods at Harrowdown Hill, the Blair government found itself in the most serious political crisis of its ten years. The very future of the government looked to be at stake at one point, and commentators and public alike speculated on this, and on the future of the BBC.

In this highly charged atmosphere, the death of Dr Kelly was central, but it was largely taken for granted from day one that he had committed suicide – aided by some like the journalist Tom Mangold, who asserted this with certainty on the morning he was found yet before any medical examination had even taken place and while the police were treating the location where he was found as a crime scene. That, and the extraordinarily speedy announcement the same day of an inquiry to be chaired by Lord Hutton, meant that basic questions that should have been asked viiiby the media about his death were lost. Bluntly, the media was much more interested in the future of the government and the BBC. The wagon train had moved swiftly on.

Neutrally, it seemed to me to be unsafe simply to assume that David Kelly had killed himself, or indeed to assume anything else. We, the public, simply had no facts, and nor, it seems, did those who were busy making definitive statements to the media.

While suicide superficially seemed the most likely explanation, suicides after all can be staged, so I kept an open mind and awaited the Hutton inquiry.

I waited in vain. The process was a travesty, and the final result provoked widespread derision and anger, as Lord Hutton cleared the government of virtually everything, and came down like an avalanche on the heads of the BBC. The result was that nobody from a government that had led us into what was almost certainly an illegal war resigned, while the BBC, which had broadcast one exaggerated, but for all that essentially true, report at 6.07 one morning, lost its chairman, its director general and the journalist who filed the report. Meanwhile, poor Dr Kelly barely got a look in.

Like many people, I felt incensed. This was an outrage.

But I had also noticed the letters that had begun to appear in TheGuardianfrom leading medical specialists, in which they queried the conclusion that Dr Kelly’s death was suicide. The letters were well argued, and I began to wonder if the Hutton report, which was so manifestly loaded in favour of the government in its political conclusions, could be trusted in respect of its analysis of how Dr David Kelly died.

And there the matter lay in abeyance, as my frontbench role for the Liberal Democrats, covering Environment, Food and ixRural Affairs, took precedence as the 2005 general election approached. I had resolved to myself, however, to look further into the whole business when time allowed and did so early the following year. I had expected to conclude in my own mind that it was probably suicide, or at the very least, that there was no evidence that it was not. But my initial enquiries led me to a rather different conclusion – that the suicide explanation was a manifestly unsafe one, and that there were a large number of important points Lord Hutton had simply not considered or had irrationally dismissed.

At that point, I made a decision. When the next Lib Dem reshuffle took place, I would give up my Environment role to devote a year or so to looking fully into both the political events of this period and Dr Kelly’s death itself. (I should add that there were other reasons why I wanted to relinquish my role, but this was a major one.)

I did not have long to wait. The forced resignation of Charles Kennedy precipitated a leadership contest, then, naturally, a new team under Sir Menzies Campbell, whom I had backed for the leadership. I turned down the invitation to carry on in my Environment portfolio, and so began a fascinating journey into the unknown, one that would take many peculiar turns.

Before I decided to announce publicly that I intended to begin this investigation, there were two related matters I needed to consider. First, I had to be sure that my constituency work would not be affected. My first duty, after all, was to the people of the Lewes constituency, whom I have been proud to represent in Parliament. I decided therefore that I would allocate to my investigations only the time that I had freed up by relinquishing my frontbench role. x

Second, there was the impact my work might have on Dr Kelly’s family. Mrs Kelly was on record as saying very clearly that she believed that her husband’s death was suicide. Furthermore, it must have been very painful for her not only to lose her husband, but to do so in the glare of the world’s media. The last thing I wanted to do was to cause the family any further grief, which I recognised might come from further media coverage.

So for a few days, I actively turned the dilemma over in my mind, and asked friends for their advice. Should I abandon the whole idea? On the one side was the fact that a good man had died in a very public way and nobody had been brought to book, whether he had been driven to suicide or murdered. There was also the fiasco that was the Hutton inquiry, and the clear public mood that this was unfinished business. On the other side was the potential impact on the family.

I decided to publish an article, carried in July 2006 by the MailonSunday, in which I set out my concerns and initial thoughts, to see what the reaction would be. It was enormous. I received hundreds upon hundreds of letters, emails and phone calls, all bar three supportive of my decision to publish my concerns, and willing me on. This was to be by far the largest response I received to anything I did in my eighteen years as an MP.

Amongst the contacts, there were about fifty or so which drew attention to curiosities in the case and suggested leads, and a smaller number, around fifteen, that actually provided specific information not hitherto in the public domain. I had to carry on.

The result was the publication of the first edition of this book in 2007, which generated a huge amount of interest and was serialised on the front page of the DailyMail. The book was shortlisted for the Channel 4 Political Book of the Year. xi

In 2008, and in the light of mounting public concern, I wrote to the then Attorney General, Patricia Scotland, to ask her to use her powers to require a proper coroner’s inquest to be held into David Kelly’s death. The justifications I cited were insufficiency of inquiry – that Lord Hutton had failed to look into the matter properly – and the emergence post-Hutton of new evidence, for example my freedom of information request that revealed there were no fingerprints on the knife allegedly used by Dr Kelly to cut his wrist. I also met with Sir John Chilcot, chair of the then ongoing Iraq inquiry, to ask him to give due weight to the death of Dr Kelly.

While my request to the Attorney General was turned down, Dominic Grieve, when he took over the post in 2010 with the change of government, decided to conduct a personal examination of the issue.

In parallel, a group of doctors who strongly disputed Hutton’s findings produced in 2009 a detailed twelve-page analysis, demolishing Hutton’s conclusion that Dr Kelly had committed suicide, and in particular arguing that cutting the ulnar artery could not have caused sufficient loss of blood to result in death.

In March 2010, shortly before he became Attorney General, Dominic Grieve noted that the public had ‘not been reassured’ that David Kelly had committed suicide. He added: ‘I am aware of the work of the doctors’ group on challenging Lord Hutton’s findings. They have made an impressive and cogent case.’

Shortly after he took up office, he received a representation from the lawyer Mark Zaid on behalf of David Kelly’s close friend Mai Pederson, referring to the important and relevant evidence she had not been able to give, and demanding that the government take steps to establish the truth concerning Dr Kelly’s death. xii

Then, in August 2010, a large and different group of doctors had a letter published in TheTimes, disputing the suicide verdict and demanding a proper coroner’s inquest. A detailed ‘memorial’ was sent to the Attorney General shortly afterwards.

The same month, a cross-party group of politicians led by the former Conservative leader Michael Howard added their voice to the calls for an inquest.

Unfortunately, the Attorney General’s re-examination consisted largely of a paper exercise, checking the information that Hutton had had access to, such as the details of the post-mortem. No new forensic tests were carried out.

It was not an open process, no interviews took place, and so those with cogent doubts about the verdict of suicide were given no opportunity to discuss this, let alone cross-examine witnesses. In my case, there was a further bar on action, in that I was now a minister in the same government as Dominic Grieve and it would have been improper to have spoken to him about this while he was undertaking his re-examination.

On the other hand, Lord Hutton and others from 2003 were given wide scope to set out their stall and of course to argue that they had been right.

In June 2011, Grieve made a short statement to the Commons indicating that he would be taking the matter no further.

But the unhappiness had not been quelled. David Halpin, a retired orthopaedic and trauma surgeon, decided to take the matter to the High Court for judicial review. His request was turned down by Mr Justice Nicol in December 2011.

For my part, I had done what I could, as I saw it, by putting together the first edition of this book and then in 2008 writing to the Attorney General to ask for a proper coroner’s inquest to xiiibe held. The need to prepare for the 2010 election, when I rightly concluded my Lib Dem colleagues and I had a good chance of ending up in government, and then my years as a minister in the coalition government that followed the 2010 election, were my new challenge.

There the matter rested for me until my attention was drawn to a scurrilous Radio 4 programme on David Kelly in 2023 in which I was traduced without warning and given no opportunity to reply. As I write, that matter is now being legally pursued.

It did, however, serve to reactivate my interest in the Kelly affair and for the first time in years, I went back over all the twists and turns of the story. Once again, I felt that same burning sense of injustice for the shameful way this had been officially dealt with. I believed back then and I believe now that the British public are entitled to a proper process according to law, entitled to a process they can have confidence in, entitled to the truth.

They have not had it. And they will not have it until such time as a properly constituted and openly accountable coroner’s inquest is held. xiv

1

Dead on Harrowdown Hill

On 17 July 2003, Prime Minister Tony Blair was in the United States being feted by the US Congress and President George W. Bush. Their adulation was such that he was being offered the rare honour of a Congressional Gold Medal. Naturally enough, Bush and his administration were hugely grateful for the Prime Minister’s decision to join the United States in its invasion of Iraq. That invasion was supposed to lead to the discovery and disposal of weapons of mass destruction and make the world a safer place. In the end, of course, no such weapons were found. But as a result of the invasion, Iraq succumbed to anarchy and violence and the world became immeasurably less safe. And now, over twenty years on, the toxic legacy finds Iraq firmly under the malevolent shadow of Iran. As foreign interventions go, it has been a disaster for the West.

Meanwhile, as Blair was lapping up the grateful plaudits from the US Congress, the man who had done more than almost any other individual on earth to contain the threat from WMD lay dead in the woods at Harrowdown Hill in Oxfordshire.

For Dr David Kelly, the UK’s leading weapons inspector, there was to be no adulation, no medal, no standing ovation. His life ended in the cold lonely woods not far from his home, his left 2wrist cut open, and three nearly empty blister packs of coproxamol tablets in his jacket pocket.

His death was of course sensational front-page news. Dr Kelly, unknown to almost everybody at the beginning of that July, had in recent days barely been absent from media headlines. Much to his chagrin he had been thrust into the harsh glare of publicity, accused of being the mole who expressed to the BBC deep concerns about the government’s ‘sexing up’ of its dossier on weapons of mass destruction.1

Had the government indeed misused, exaggerated or even invented intelligence in order to justify the US–UK invasion of Iraq? For Blair the stakes could not have been higher. This was undoubtedly the greatest crisis of his premiership to date.

To add fuel to the flames, Blair’s director of communications, Alastair Campbell, and the government had launched an unprecedented and vitriolic attack on the BBC, questioning its integrity and professionalism in the way it reported the doubts expressed by the BBC’s source.

It is not surprising therefore that the news of Dr Kelly’s death was seen by the wider world largely as a highly political incident, rather than the tragedy that it was for the individual, his family and friends.

The media, the political establishment, indeed almost everybody accepted as fact, and without any evidence being considered, the suggestion, put forward immediately after his body was discovered, that Dr Kelly had committed suicide. With the political temperature high, media attention was instead directed that same day towards the consequences for the government, and indeed the BBC, and away from what has subsequently been shown to have been a rather strange death. In all the 3column inches devoted to this extraordinary episode in the days following Dr Kelly’s death, I was not able to find one journalist who bothered to question the assumption that this was an act of suicide, until Peter Hitchens did so in his article of 27 July 2003 in the Mail on Sunday. But his was very much a lone voice. The question the media was interested in was not how David Kelly died, but whether Downing Street, through the pressure it had placed on him, had blood on its hands. The lightning speed with which the Prime Minister acted to establish an inquiry into the whole business under Lord Hutton – within hours of Dr Kelly’s body being found – further concentrated attention on the politics, and away from the death itself.2

The next morning, a Saturday, Dr Kelly’s widow, Janice, along with one of their three daughters, was taken in an unmarked police car to the John Radcliffe Memorial Hospital in Oxford, where at 11.25 Mrs Kelly formally identified her husband. Afterwards, at around 2 p.m., Thames Valley Police issued the following statement:

‘A post-mortem has revealed that the cause of death was haemorrhaging from a wound to the left wrist. While our enquiries are continuing, there is no indication at this stage of any other party being involved.’

It seemed an uncontroversial statement. Yet in specifying the alleged cause of death, Thames Valley Police were displaying a certainty that on closer examination could not be justified by the facts. It also has to be asked whether determining the circumstances of the death was not a matter that should have been left to the Oxfordshire coroner, Nicholas Gardiner, or indeed Lord Hutton, given that he had just been tasked with investigating ‘the circumstances surrounding the death of Dr David Kelly CMG’. 4

The official version of events, then, is that Dr Kelly found himself under tremendous personal pressure as a consequence of suddenly becoming front-page news. By his own admission, he had discussed the war in Iraq, and specifically the way the available intelligence had been used to justify the invasion, with a number of BBC journalists, including Andrew Gilligan, who was to play such a major part in the whole David Kelly episode. This had led to a very uncomfortable time in a televised session before the Foreign Affairs Committee in the House of Commons on the Tuesday before his death. The pressure continued in the forty-eight hours after that, including demands for further details of his journalist contacts. Dr Kelly feared he had been caught out lying, and, as a man of considerable integrity, felt wretched. He may also have feared he would lose his job when his managers at the Ministry of Defence (MoD) fully established this. Perhaps a call from the ministry on the Thursday confirmed the worst. Perhaps under all this pressure, he buckled and decided to commit suicide.

Having so decided, the official version continues, he then left his house in Southmoor, Oxfordshire, at about 3 p.m. on Thursday 17 July 2003, taking with him a knife he had had since boyhood and thirty coproxamol tablets. He took a familiar path into an area of woodland he knew well, and then, in a secluded and private spot, cut his wrist and swallowed twenty-nine of the thirty tablets he had brought. His body was officially discovered at around 8.30 the following morning.

Lord Hutton summarised the death thus in his report:

In the light of the evidence which I have heard I am satisfied that Dr Kelly took his own life in the wood at Harrowdown Hill at a time between 4.15 p.m. on 17 July and 1.15 a.m. on 18 5July 2003 and that the principal cause of death was bleeding from incised wounds to the left wrist which Dr Kelly inflicted upon himself with the knife found beside the body. It is probable that the ingestion of an excess amount of Coproxamol tablets coupled with apparently clinically silent coronary artery disease would both have played a part in bringing about death more certainly and more rapidly than would otherwise have been the case. Accordingly the causes of death are:

1a Haemorrhage

1b Incised wounds to the left wrist

2 Coproxamol ingestion and coronary artery atherosclerosis.3

Lord Hutton went on to say that he was satisfied no third party was involved, that it was ‘highly unlikely’ that a third party could have forced Dr Kelly to swallow a large number of coproxamol tablets, and that Dr Kelly was suffering from no ‘significant mental illness’ at the time of his death.

That, then, is the official version. It is faulty and suspect in virtually all important respects, as we shall see.

David Christopher Kelly was born in the Rhondda valley on 14 May 1944. His father, the son of a coal miner, was then a signals officer in the RAF. His mother, the daughter of a gravestone sculptor, was a schoolteacher. They were married in Pontypridd just after Christmas in 1940, and later moved to Tunbridge Wells. Within two years, however, his parents were divorced, and David, their only child, was taken back to live in Pontypridd with his mother and his grandmother, Ceinwen Williams. Friends at school remember him talking warmly of his grandmother, but rarely of either parent. 6

His father married another woman, Flora Dunn, just two weeks after his divorce was made official. She was ten years his junior. Together they settled in Kettering and started a new family. He became head teacher at a local school. Eventually they had three children, and adopted a fourth, but David was never asked to live with them. His father died of lung cancer, aged sixty-six.

His relationship with his mother appears to have been little better. It must still have been traumatic for him, however, when she was found dead at her cottage in Pontypridd on 13 May 1964, the day before his twentieth birthday. Aged just forty-seven, she had taken an overdose of sleeping pills.

The question inevitably arises whether this tragic incident was in Dr Kelly’s mind on 17 July 2003. It turns out that the subject of his mother’s suicide came up in conversation many years later with a close friend, another weapons inspector, whose brother had recently taken his own life. It was at that point that Dr Kelly revealed that his mother had also died by her own hand. His tone, by all accounts, was slightly dispassionate and quite balanced. No one can say with certainty that this tragic incident in Dr Kelly’s youth did not prey on his mind throughout his life, but his colleague was given no impression that it did so. It had certainly affected him deeply at the time.

David Kelly’s answer to his emotionally difficult childhood appears to have been to throw himself into his work, an approach that persisted throughout his life. At grammar school, he rose to become head boy, and his application also led him to excel in athletics. He went on to study bacteriology at Leeds University, where he met his wife to be, Janice, a student teacher. They were married near her family home in Crewe in 1967. He 7was twenty-three, and she twenty-two. The couple were to have three daughters: Rachel and Ellen, who were twins, and Sian.

Leeds was followed by Birmingham, where David took another degree, followed by time at Oxford, where he studied for his doctorate. The family moved to Oxfordshire in 1974.

His career in the public sector began in 1973, when he was appointed as a senior scientific officer in the Unit of Invertebrate Virology at the National Environment Research Establishment, a post he held for eleven years, including a promotion to the post of principal scientific officer in 1982. During his time there, he specialised in the field of biological control applicable to agriculture, in particular the use of viruses to attack insect pests.

In July 1984 Dr Kelly joined the Ministry of Defence as head of what was then the Chemical Defence Establishment at Porton Down, near Salisbury. He led the research into ways to enhance the defence of troops in battle against biological warfare. This research proved particularly useful in the field in 1991, during the war over Kuwait. He also directed the decontamination of Gruinard Island, off the north-west coast of Scotland, used in the Second World War to test anthrax weapons.

His first involvement in the murky world of weapons inspection came in 1989, when he was used as a technical expert to assess the disturbing data then emanating from the Soviet Union, largely through defectors such as Vladimir Pasechnik. From 1991 onwards, David Kelly began to participate in on-site inspections abroad, and soon proved his worth, through both his expertise and his approach. He was rewarded in 1992 with an individual merit promotion to Grade 5. In simple terms, this gives the recipient the freedom to focus on research without the responsibility for managerial work normally associated with a 8Grade 5 employee. In July of that year, he was appointed senior adviser in biological defence at Porton Down. From 1992 onwards, Dr Kelly increasingly found himself working on inspection duties for the United Nations Special Commission, and was appointed senior adviser to that body in 1995.

In April 1996, Dr Kelly was seconded to the MoD’s Proliferation and Arms Control Secretariat, also working as an adviser to the non-proliferation department of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office on Iraq’s chemical and biological weapons capabilities. He briefed both the Defence Intelligence Staff and MI6 on these matters. Significantly, given subsequent events, he was also expressly tasked with communicating information relating to Iraq’s weapons activities to the media. Additionally, Dr Kelly contributed to the work of the United Nations Monitoring Verification and Inspection Commission, advising on chemical and biological weapons and helping to train weapons inspectors.

Less publicly, part of Dr Kelly’s work involved liaising with the Rockingham Cell, described by US weapons inspector Scott Ritter as a ‘secretive intelligence activity buried inside the Defense Intelligence Staff which dealt with Iraqi weapons of mass destruction and activities of the UN Special Commission’.4 It has also been referred to by Michael Meacher MP as a ‘clearing house’ which received and analysed intelligence data on Iraqi capabilities.5 And according to the Sunday Times journalist Nick Rufford, Dr Kelly had ‘sometimes [been] an undercover man for the intelligence services’.6

David Kelly had come a long way. As we shall see, he had established himself as the leading weapons inspector in the UK, and possibly in the world. He was highly respected both by those 9he worked alongside and those he challenged, in countries such as Russia and Iraq.

In 1996, his ‘service in relation to foreign affairs’ led to his becoming a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in the Queen’s birthday honours list of that year. Before the events of July 2003 overtook him, he was being actively considered for a knighthood.7 It would have been a fitting crown to his career, as he contemplated retirement. But it was not to be.

Aged fifty-nine, Dr David Kelly was dead, alone on Harrowdown Hill. 10

NOTES

1 The dossier’s full title is Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction: The Assessment of the British Government. Published 24 September 2002.

2 In a letter dated 24 July 2003, the Secretary of State for Constitutional Affairs and Lord Chancellor, the Right Honourable Lord Falconer of Thoroton, acting on behalf of the government, wrote to Hutton asking him to ‘conduct an inquiry within the following terms of reference: urgently to conduct an investigation in to the circumstances surrounding the death of Dr Kelly’.

3 Lord Hutton, Report of the Inquiry into the Circumstances Surrounding the Death of Dr David Kelly CMG, HC 247, 28 January 2004.

4 Scott Ritter, ‘The public must look to what is missing from the report’, Guardian, 30 January 2004.

5 Michael Meacher, ‘The very secret service’, Guardian, 21 November 2003.

6 Nicholas Rufford, ‘Spy, boffin, disgruntled civil servant: this was the David Kelly I knew’, Sunday Times, 25 January 2004.

7 Letter from Eric Matthew, honours secretary, 23 May 2003, inviting suggestions with David Kelly’s name handwritten across the top. Hutton inquiry evidence reference FAM/5/0001-0005.

2

‘Was Kelly murdered?’

The headline screamed out from the London Evening Standard on Tuesday 27 January 2004. It followed the publication, with somewhat less fanfare, it has to be said, in that morning’s Guardian of a letter from three specialist medical professionals, questioning the conclusion that David Kelly had committed suicide. The letter was signed by David Halpin, a specialist in trauma and orthopaedic surgery, Stephen Frost, a specialist in diagnostic radiology, and Searle Sennett, a specialist in anaesthesiology.

Throughout 2004, further letters to The Guardian would follow in which other health professionals expressed their doubts about the verdict. These would include John Scurr and Chris Burns-Cox, respectively specialists in vascular surgery in internal general medicine. By the end of the year, the medical experts numbered ten, and they were joined by Michael Powers, a leading QC with particular knowledge of coronial matters. Together, they formed a loose association called the Kelly Investigation Group. What linked them were the significant doubts they held about the official explanation given for the death of Dr Kelly, and the affront they felt at the way the whole Hutton inquiry was handled.

The doubts of the medical experts would, however, take centre stage only briefly in the media, for the following day, 28 January, 12the conclusions of the much awaited Hutton report appeared on the front page of The Sun, ahead of the official publication time, and the attention of the media and politicians alike reverted to where it had been during the previous six months, namely fixed on the political implications of Dr Kelly’s death for the government and the BBC.

Lord Hutton’s unbelievably one-sided report, which castigated the BBC and gave the government a clean bill of health, led shortly afterwards to the resignations of the BBC’s chairman and its director general, Gavyn Davies and Greg Dyke respectively.1 Andrew Gilligan, the reporter at the centre of the controversy, would follow shortly afterwards.2

We then had to endure the appalling sight of the BBC’s acting chairman, the former Conservative MP Richard Ryder, making an unreserved and obsequious public apology to the government, bad enough if the BBC had committed some heinous act but unforgivable as it had not. Richard Ryder stupidly undermined seventy years of independent journalism and the BBC has to a large extent been pulling its punches ever since. He did more damage to the BBC in ten minutes than anyone else ever has.

Predictably, no minister from the government resigned, or even apologised for any actions they had taken, though it might be argued that Alastair Campbell’s resignation the summer before had been precipitated by these events, though that had been officially denied.

There was some suspicion at the time that the publication of the Hutton report’s main findings in The Sun had been deliberately engineered in order to deflect attention from the Evening Standard’s front page the previous evening, or at the very least 13that it represented some dark trading between Campbell and the government’s favourite paper. In fact, neither of these two explanations is true. The scoop was actually secured thanks to an enterprising piece of work by the affable Sun journalist Dave Wooding, now editor of the Sunday Express, who thus earnt himself a nice bonus. In the paper itself, though, Trevor Kavanagh, the political editor, got the byline and the credit.

The publication of the Hutton report, coming as it did swiftly on the heels of the doubts expressed by the health professionals, was unfortunate in its timing, for the objections that had been raised to Lord Hutton’s opinion that Dr Kelly’s death was suicide were serious ones and deserved much fuller consideration than they were given. In their letter to The Guardian, the three medical experts described as ‘highly improbable’ the suggestion that Dr Kelly had bled to death by a self-inflicted wound to his left wrist. At the Hutton inquiry, the pathologist employed to carry out the post-mortem, Dr Nicholas Hunt, stated that only one artery had been cut in Dr Kelly’s wrist, the ulnar artery. As the letter to the paper pointed out, arteries in the wrist are of matchstick thickness and severing one of them does not lead to life-threatening blood loss.

John Scurr, the specialist in vascular surgery who added his name to what was by then the sixth letter from medical experts to The Guardian in 2004, told me that in his opinion, it was just about possible to die from a cut to the ulnar artery, if the artery were sliced away at, but not if it were cut transversely, as we are told was the case here. David Halpin, the former senior orthopaedic and trauma surgeon at Torbay Hospital and at the Princess Elizabeth Orthopaedic Hospital in Exeter, believes even the deepest cut to this artery would not have caused death. ‘A 14transected artery, one that has been completely cut, retracts immediately and thus stops bleeding, even at a relatively high blood pressure,’ he told me.

So it is extremely difficult to kill yourself by cutting your wrist. Of course, people can die from wrist or arm cutting, but it requires some basic medical knowledge to be successful. The cut should be lengthwise along the arm rather than across the wrist, and even then it is likely to result in death only if the person concerned is sitting in a warm bath. Others, with less medical knowledge, will tend to slit their wrists crosswise, thereby severing the radial artery. Neither group would actually choose to sever the ulnar artery. The choice of this artery would make sense, however, if the hand were held by another, and the cut administered by that person.

There is a further consideration which argues against the suggestion that the cutting of the ulnar artery would be a chosen method of suicide. The artery in question is hidden deep in the wrist on the little finger side of the hand, and can only be accessed by cutting through nerves and tendons, an extremely painful process. It is not common for those who commit suicide to wish to inflict significant pain upon themselves as part of the execution of that process.

Certainly the incidence of individuals dying from a severed ulnar artery is a rarity according to official statistics. Karen Dunnell, the national statistician at the time, confirmed to me in writing that there had been only six individuals who had died from injury to the ulnar artery between 1997 and 2004. Of these, three were suicides, two accidents, and one had ‘an underlying cause of injury of undetermined intent’. Only one such death occurred in 2003, the year of Dr Kelly’s death. 15

The information provided by the national statistician comes from tables provided by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases.3 An examination of these tables shows that in fact the only person to have died in 2003 from injury to the ulnar artery was aged 25–29. There are three individuals aged 55–59 who are shown as having died from ‘injuries to the wrist and hand’ so it is possible that Dr Kelly’s death was categorised thus. There is also one from that age bracket listing as having died from ‘superficial injury of wrist and hand, unspecified’ and two from ‘open wound of wrist and hand part, part unspecified’: just six out of a total of 12,286 deaths of men aged 55–59 in 2003.

The official statistics take cause of death from the death certificate and, as we have seen, that gave the primary cause of death as ‘haemorrhage’ and ‘incised wounds to left wrist’. The fact remains that however the death has been categorised, mortalities due to wrist and hand injuries are extremely rare.

For the general public, the suggestion that someone may have died from slashing their wrists will come as no great surprise. It has, after all, been the staple diet of books, films and television programmes over the past century or so. In fact, official figures show that cutting any part of one’s body open is a relatively rare method of achieving suicide. In the UK in 2003, there were a total of 4,659 suicides, including ‘injuries of undetermined intent’, of which just 236 were of men aged 55–59. Of the 4,659, 126 were classified under the heading ‘contact with sharp object’. By far the most successful methods chosen were hanging, strangulation and suffocation, responsible for 1,921 suicides, and drug-related poisonings, responsible for 1,159.

Further evidence for the ineffectiveness of wrist or arm cutting as a method of attempting suicide comes from a report 16produced in 1998 by Geoffrey McKee, ‘Lethal versus Nonlethal Suicide Attempts in Jail’,4 which analysed suicide attempt reports from all South Carolina jails between 1985 and 1994. The report shows that, perhaps in line with public misconceptions, wrist or arm cutting was the second most common method chosen by inmates in attempts to end their lives. In fact 275 prisoners, 28.7 per cent of the total, attempted suicide in this way. The figures also show, however, that only one death resulted from these 275 attempts. Other methods chosen, most notably hanging and swallowing substances, were statistically much more successful.

In psychological terms, those who choose to slit their wrists may frequently be making a cry for help, rather than seriously attempting to kill themselves. In Dr Kelly’s case, the unlikelihood of the proposition that he would attempt to kill himself by cutting this artery is further compounded by the weapon he apparently chose for this purpose. This was, we are told, a blunt concave pruning knife, one with a little hook or lip towards the top of the blade. The use of such a knife would only have increased the pain and would also have failed to cut the artery cleanly, thereby hastening the clotting process and so limiting the loss of blood further.

The knife in question had in fact been owned by Dr Kelly since his boyhood, so it might just be argued that the use of this particular weapon was chosen for sentimental rather than practical reasons. Nevertheless the sheer inappropriateness of this particular knife makes it difficult to believe that Dr Kelly would have acted in this way. Furthermore, we were to learn from the pathologist, Nicholas Hunt, that the wound to Dr Kelly’s wrist showed ‘crushed edges’, suggesting that the knife was blunt. This made it an even more inappropriate weapon to choose. A further 17objection is that Dr Kelly undoubtedly knew more about the human anatomy than most people, and the idea that he would have chosen such an uncertain and painful method to commit suicide is not easy to sustain.

It might be argued that Dr Kelly did not leave his house in Southmoor that Thursday afternoon with the intention of committing suicide, but that a black mood came upon him in the woods and the decision was spontaneous. He then found that the only weapon to hand was this knife and used it as best he could to effect that purpose. This theory, however, simply does not hold water, if we are also to believe that Dr Kelly brought with him from his cottage thirty coproxamol tablets, which, according to the official version of events, were used either to dull the pain of the incision or to provide a second parallel method of achieving suicide. The presence of the coproxamol tablets, if they are part of a suicide plan on Dr Kelly’s part, clearly implies premeditation.

Coproxamol is itself a frequent cause of death, either by suicide or by unintentional overdosing, often in association with alcohol. Between 1997 and 1999 there were on average 255 deaths per year by coproxamol poisoning in England and Wales. Discounting those deaths where accidental overdosing is thought to be the explanation, coproxamol is still associated with 5 per cent of all suicides in that period. It was in fact the second most commonly used drug in overdose suicides.

Dr Kelly, we are led to believe, removed from his house three blister packs, each containing ten coproxamol tablets, whose active ingredients were 325 milligrams of paracetamol and 32.5 milligrams of dextropropoxyphene. Police investigations confirmed that the tablets came from the same batch as the ones 18Janice Kelly had at home (although this batch ran to 1,600,000), who had been taking them for her arthritis, so it seems likely that they were taken from their house.

We are told that the police found that twenty-nine of the tablets had been removed from their trays – doubtless the one that David Kelly thoughtfully left helped the police with their enquiries. Dr Kelly had apparently also very considerately replaced the empty blister packs inside the pocket of his wax jacket, found at the scene. The clear implication therefore was that Dr Kelly had consumed the twenty-nine tablets. Subsequent medical tests, however, revealed the presence of only the equivalent of a fifth of one tablet in his stomach. Even allowing for natural metabolising, these two figures cannot easily be reconciled. There were vomit stains visible on his face when the body was found, though we subsequently discovered that no analysis of them was carried out to establish the contents of the vomit. In any case, if the tablets had been regurgitated, they can hardly have been a contributory factor in his death.

Alexander Allan, the forensic toxicologist at the Hutton inquiry, gave evidence that although levels of coproxamol in the blood were higher than therapeutic levels, the blood level of each of the drug’s two main components – paracetamol and dextropropoxyphene – was less than a third of what would normally be found in a fatal overdose.5 Furthermore, it is generally accepted that concentrations of a drug in the blood can increase by as much as tenfold after death, leaving open the possibility that Dr Kelly consumed only a thirtieth of the dose of coproxamol necessary to kill him.

But just as there were objections to the alleged choice of weapon by Dr Kelly, so too is there an objection to his apparent 19use of coproxamol tablets. Mai Pederson, who was serving in the US Army, had been a close friend of Dr Kelly’s since 1999. She has said on record that Dr Kelly had an aversion to swallowing tablets, an observation in fact which Mrs Kelly also confirmed at the Hutton inquiry. So we are being asked to believe that Dr Kelly indulged in a further masochistic act in an attempt to take his life.

Details emerged of an occasion when Ms Pederson was at the Kelly house in Southmoor and was actually offered coproxamol tablets by Janice Kelly to help relieve some pains she was experiencing. Ms Pederson accepted, but Dr Kelly criticised his wife for offering tablets prescribed for her alone. If true, this can only reinforce the doubts that exist that Dr Kelly would actually have chosen to ingest twenty-nine of these tablets.

A further objection is that police evidence states that there was a half-litre bottle of Evian water by the body which had not been fully drunk.6 Common sense tells us that quite a lot of water would be required to swallow twenty-nine tablets, particularly ones such as these, oval with a long axis of about half an inch. It is frankly unlikely, with only a small water bottle to hand, that any water would have been left undrunk. In addition, Roy Green, the forensic biologist who was called to the scene at Harrowdown Hill on the Friday, told the inquiry that ‘when people are injured and losing blood they will become thirsty’.7 He thought it very likely that Dr Kelly would have drunk water after cutting himself, if that is what happened, thereby reducing further the amount that would have been consumed to swallow the twenty-nine tablets. He confirmed that there were blood smears on the water bottle.

Nor is death from coproxamol overdose a quick and painless 20experience. According to the Medicines and Health Care Products Regulatory Agency, early symptoms include severe respiratory depression and convulsions. Pallor, nausea and vomiting may persist for twenty-four hours and psychotic reactions may occur. After between one and three days, features of hepatic necrosis (death of the liver tissue) may appear, followed by jaundice. It is a slow and painful way to go. Coproxamol was at the time undergoing a phased withdrawal, completed by the end of 2007.8

At the very least, Dr Kelly would have known that to overdose on coproxamol could have left him alive but medically damaged. Would he have wanted to risk creating such a burden for either himself or his family? Similarly, he would have known that to cut the ulnar artery could well have left him alive, suffering in extreme pain and with a hole in his wrist. Interestingly, the Times of Saturday 19 July 2003 quoted ‘a police source’ as saying that they ‘had ruled out an overdose, or use of a gun in the death’. It seems they too were unconvinced by the argument that he could have been killed by coproxamol poisoning.

If David Kelly had genuinely wanted to commit suicide, he would have made sure that his chosen method was an effective one. Are we really expected to believe that someone of the knowledge and maturity of David Kelly would have decided upon such an inept, uncertain and painful way to kill himself?

Medical experts have also seriously questioned the amount of blood which Dr Kelly actually lost. An adult human body contains about eight pints of blood, of which about half has to be lost to cause death. The effects of four pints of blood spurting from a body cannot be hidden. Yet the two searchers who found the body initially did not even notice that Dr Kelly had apparently incised his wrist with a knife. In addition, the two 21paramedics who arrived on the scene shortly afterwards pointedly referred to the fact that there was remarkably little blood around the body when they subsequently gave evidence to the Hutton inquiry.9 One of the paramedics, Vanessa Hunt, was not asked about this, but volunteered her view anyway. She told Lord Hutton:

The amount of blood that was around the scene seemed relatively minimal and there was a small patch on his right knee, but no obvious arterial bleeding. There was no spraying of blood or huge blood loss or any obvious loss on the clothing … There was dried blood on the left wrist … but no obvious sign of a wound or anything, it was just dried blood.10

Ms Hunt’s colleague, Dave Bartlett, confirmed her observations, reporting no blood stains on the clothes apart from a one-inch stain on the trousers over the right knee, the likely result of Dr Kelly kneeling in blood.11

Dr Bill McQuillan, a former consultant at Edinburgh’s Royal Infirmary, ran a clinic on peripheral nerve injuries for twenty years, which dealt with quite a few patients with arterial injuries. He told the Daily Express:

Arterial bleeding is quite dramatic. In surgery you have to divide small arteries from time to time, and blood sprays out like a kid’s water pistol. What you see is a pump action with each beat of the heart and I have known it hit the ceiling. If the bleeding was as small as alleged, that is astonishing.12

Lord Hutton was to place considerable emphasis on his evidence 22of Roy Green, the forensic biologist who testified at the inquiry. Mr Green confirmed that a cut to an artery would indeed have led to blood spraying out, as Dr McQuillan would later suggest. He termed the phenomenon ‘arterial rain’, and said there was evidence of blood deposits on the nearby nettles. It is possible but unlikely that the blood may have spurted out in a fountain-like manner, thereby leaving the clothes relatively untouched.

Nicholas Hunt, the inquiry pathologist, told the inquiry that in his view the injuries to the wrist had been inflicted a matter of minutes before his death. He gauged this by observing what he called ‘a well-developed vital reaction’,13 which he explained as the body’s response to an area of damage, in this case reddening and swelling around the area of the left wrist. We are thus led to conclude that the blood loss was so enormous, and the rate of loss so fast, that Dr Kelly died in minutes following the cut to the tiny ulnar artery, yet with the paramedics observing how little blood there was around, and with Dr Kelly’s clothes largely unspoilt.

David Halpin told me that even if you knew enough about the human body to choose the most effective artery to sever, probably the groin, it would still take well over half an hour to die. It is, he suggested, well-nigh impossible to die by severing the ulnar artery alone, and certainly not within a matter of minutes. ‘Surgeons know rather more about arteries than pathologists do,’ was how he rather witheringly put it to me.

Yet if this cut was not the cause of death, then the clear implication is that he died from a different cause, with the cut to the wrist merely there to provide a diversion.

The conclusions from this are clear. Either Dr Kelly did not lose very much blood, which is after all consistent with a cut to 23the ulnar artery, whether before or after death, and so died from a different cause. Or he did lose the required amount to cause death but that this happened elsewhere and his body was moved to the location in which he was found. Both scenarios imply the involvement of another party. Neither was properly considered by the Hutton inquiry.

So concerned were the ambulance crew, Dave Bartlett and Vanessa Hunt, both paramedics for more than fifteen years at the time, that in December 2004 they went on record in an interview with the respected Observer journalist Antony Barnett to question the official version of events.

‘There wasn’t a puddle of blood around,’ Ms Hunt told the reporter. ‘There was a little bit of blood on the nettles to the left of his left arm. But there was no real blood on the body of the shirt. The only other bit of blood I saw was on his clothing. It was the size of a 50p piece above the right knee on his trousers … When somebody cuts an artery, whether accidentally or intentionally, the blood pumps everywhere. I just think it is incredibly unlikely that he died from the wrist wound we saw.’ She also revealed that there was no blood at all on his right hand. ‘I didn’t see any blood on his right hand … If he used his right hand to cut his wrist, from an arterial wound you would expect some spray.’

The two paramedics told Mr Barnett that over the years they had raced to the scenes of dozens of suicide attempts where someone had slit their wrists. In only one case had the victim been successful. Referring to that occasion, Ms Hunt said: ‘That was like a slaughterhouse. Just think what it would be like with five or six pints of milk splashed everywhere.’14

Nor has time changed their views. Mr Bartlett told me that they ‘stand by everything we have said 100 per cent’. 24

The inquiry was not told how much blood Dr Kelly was estimated to have lost, despite this being a key statistic. Indeed, no attempt seems to have been made to establish this figure, though it is not particularly difficult to do so. An objective method used is first to measure the blood volume in the body. Next, an analysis of the soil into which the blood would supposedly have soaked can have the haemoglobin leeched out and measured.

There is one further oddity related to the blood, referred to by Ms Hunt above, namely the blood mark on Dr Kelly’s right knee. Roy Green, in his evidence, referred to this as a ‘contact blood stain’, brought about, he suggested, by Dr Kelly kneeling in a pool of blood. Quite why, having cut his wrist, he would then need to get up from either his lying or his sitting position to kneel is far from clear.

As well as the incision to the wrist and the ingestion of coproxamol tablets, both the official death certificate and Lord Hutton refer in passing to Dr Kelly’s alleged heart condition. It is worth noting that Dr Kelly’s own GP, Dr Malcolm Warner, who was called to give evidence at the Hutton inquiry, appeared to know nothing about this. To the question ‘Were you aware of any serious medical condition from which Dr Kelly suffered?’, he answered with a simple ‘No’.15 Indeed, his evidence revealed that Dr Kelly had less than two weeks before his death, on 8 July, undergone a medical for the Ministry of Defence in preparation for yet another trip to Iraq. That medical revealed no problems and he was cleared to go. His general state of health was said to have been good. Dr Warner had not been consulted by David Kelly since 1999. It is indeed a mystery how both Lord Hutton and the coroner were able to discover that Dr Kelly suffered from ‘coronary artery atherosclerosis’, or hardened arteries, when this fact 25appeared to have bypassed both his own GP and those carrying out the MoD medical.

Dr Nicholas Hunt was the pathologist chosen by the Oxfordshire coroner, Nicholas Gardiner, to undertake the post-mortem and associated matters, and who advised that the causes of death were those which duly appeared on the death certificate.

Of the forty-three names on the Home Office register of forensic pathologists deemed to have sufficient qualifications, training and experience, to be instructed in cases of suspicious or violent death, Dr Hunt’s was one of the most recent additions, having been added only in 2001. The list included many far more experienced pathologists, some of whom had been entered on the register as far back as 1978. It is curious therefore that the Oxfordshire coroner should have made this choice, particularly as this was an extremely high-profile death commanding front-page headlines. Under the circumstances, Mr Gardiner could have been forgiven for employing the most experienced pathologist he could find from the register, or even employing two such people.

In 2010, the Daily Mail would report that Nicholas Hunt was still under a five-year warning for breaking General Medical Council guidelines. He was given the caution for using a seminar to show photographs of the mutilated bodies of three Royal Military Police killed in Iraq in June 2003.

Dr Hunt arrived at the spot where Dr Kelly lay at around noon on the Friday, some two and a half hours after the corpse was first discovered. It must be said that, given the sensational and highly political environment surrounding this death, he might perhaps have been expected to arrive rather more promptly. He approached the body and began a visual examination and 26confirmed death some twenty-five minutes later. He did not carry out a more detailed examination until a further hour and a half had passed, after the fingertip search conducted by the police had been completed. By this point, a scene tent had been erected. The police erected two tents, a blue one over the body and a white one on the edge of the wood, which provided a place to fill in paperwork out of wind or rain. It is worth noting that the police were treating the death as potentially suspicious at this point.

Dr Hunt told the inquiry that the procedure he adopted was to retrieve as much trace evidence as possible, including looking for fibres, or DNA contamination by a third party. He also at that stage noticed an area of blood staining to the left side of the body, across the undergrowth in the soil. It is not clear how much blood may have caused this area of staining, nor even if it matched Dr Kelly’s DNA, though we are implicitly invited to assume it does.

In order to place the time of death accurately, it is standard practice to take the rectal temperature of a body as soon as possible. As the body cools towards the temperature of the surrounding environment, it becomes increasingly difficult to be specific about the time of death. Oddly, having arrived at noon, and begun his detailed examination at around 2 p.m., it was not until 7.15 p.m. that Dr Hunt actually took the rectal temperature, just four minutes before he left. As a consequence he was able to provide the inquiry with only a very wide window within which death may have occurred, namely between 4.15 p.m. on the Thursday and 1.15 a.m. on the Friday. Dr Hunt arrived at this window by estimating that death occurred between eighteen and twenty-seven hours prior to taking the rectal temperature. The fact that his estimate is based on this observation serves only to 27reinforce the importance of this procedure in determining time of death.

Why did he not take the temperature as soon as he had access to the body? The review of the death undertaken in 2010 by the then Attorney General Dominic Grieve suggests that this was to ensure a potential crime scene was not compromised. A proper consideration, but surely taking the rectal temperature would not have been inconsistent with that.

Another method to help determine time of death is the test for livor mortis, or post-mortem lividity. Upon death, with the heart no longer pumping, the blood begins to settle in the lower part of the body, and the denser red cells sink through the blood by the force of gravity, causing a purplish-red discolouration of the skin. Livor mortis starts between twenty minutes and three hours after death, and is congealed in the capillaries in four to five hours. Maximum lividity occurs within six to twelve hours.

Dr Hunt told the Hutton inquiry that he found livor mortis to be a clear post-mortem feature. Yet if Dr Kelly died from a massive loss of blood, as we are told he did, then significant livor mortis simply would not have occurred. Put simply, there would not have been enough blood.

Rigor mortis begins to set in after six hours at the latest, and within eight to twelve hours the body is completely stiff. It then remains stiff for a further twelve hours or so, before the process begins to reverse. It follows therefore that a standard assessment of rigor mortis helps to narrow down the time of death more accurately.

The Hutton inquiry did not hear evidence about the onset of rigor mortis, but Dr Hunt’s report, which was made public in 2011, states that it was ‘fully established in all muscle groups’ by 285.30 p.m. on that Friday. We also know that the paramedics had to move Dr Kelly’s arm off his chest. That would suggest that rigor mortis had not fully set in at that point, placing the time of death early on the Friday morning. If that was the case, where was Dr Kelly in the ten or more hours between leaving his house and his death?