11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Liberties Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

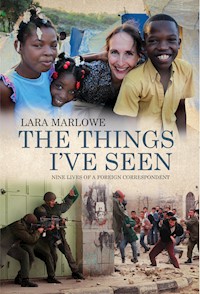

Lara Marlowe, the Washington correspondent of The Irish Times, has witnessed more than her share of history in three decades as a foreign correspondent. She has reported with clarity and fearlessness on the main conflicts of our era, from the civil war in Lebanon to the break-up of Yugoslavia, the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq and the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. She has been outspoken in her criticism of the often cruel and misguided actions of the world's leading powers, and invariably seeks out the views of civilians caught up in wars that are not of their making. The human cost of conflict and the absurdity of war come through her work, time and again. In this stunning and moving collection, Lara Marlowe has chosen her finest pieces of writing from her years as a foreign correspondent in some of the world's most troubled countries - notably Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, Iraq and Haiti - as well as the power centers of Paris and Washington. She brings her keen insight to bear on some intractable problems, and shares with the reader the terror of living in a war zone. There are lighter moments too: a wonderful house-warming party in Beirut during a lull in artillery bombardments; meetings with talented celebrities, including Carla Bruni, Isabelle Adjani and Marcel Marceau; the simple delight of the companionship of cats. This is a superb collection from a writer at the height of her powers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

THE THINGS I’VE SEEN

Nine Lives of a Foreign Correspondent

Lara Marlowe

For Michel and Chantal Déon

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Acknowledgements

Preface: A Life in Journalism

I FRANCE

Douce France

City of My Life, 14 July 2001 and 2 August 2004

A Last Farewell, 19 April 2010

La France de Sarkozy

Nicolas Sarkozy’s Victoire Extraordinaire, 7 May 2007

Europe Gets Set for the Sarkozy Treatment, 8 July 2008

Why Obama and Sarkozy Can Never Truly Be Friends, 3 April 2010

Mes Français

Isabelle Adjani, 13 January 2001

Marcel Marceau, 27 January 2001

Jeanne Moreau, 30 November 2002

Michel Déon, 21 May 2005

Carla Bruni, 29 November 2008

Sophie Toscan du Plantier, 11 December 1999 and 10 May 2008

History Is Ever With Us

Has the French Revolution Ever Ended?, 14 July 2009

II LEBANON & ALGERIA

Lebanon

Going West in Beirut, 9 January 1988

A Civilisation in Ruins, 24 June 1989

‘Normal Life’ in Beirut, 5 August 1989

Poems for Lara: One of Beirut’s Innocents, 21 July 1990

The Qana Massacre, 29 April 1996

Algeria

Dying to Go to School, 28 June 1997

Massacre at Bentalha, 21 October 1997

Killed for a Column, 2 May 1998

Lebanon

‘I trust you, Lara. Don’t betray me’, 15 February 2005

Merci, Cheikh Rafiq, 5 April 2005

Search for Bodies Ends in Failure, 2 August 2006

‘I am very happy, because we are winning’, 4 August 2006

Fear, Blood, Rubble, Sorrow, 12 August 2006

III YUGOSLAVIA

Sarajevo Waits for Winter, 12 October 1992

Stealth Fighter Crashes into a Time Warp, 29 March 1999

Kosovo Refugees Die Under NATO Bombs as the Serbs Expel Them, 17 April 1999

NATO Bombs Television Station, 24 April 1999

Arkan: A Symbol of All That Was Wrong with Yugoslavia, 17 January 2000

IV IRAN

Real Bodies, Unreal Words, 14 July 1988

Chador Gives Way as Attitudes Soften in Iran, 23 February 2000

Iran’s Lost Generation, 26 February 2000

Awaiting Mehdi and the End of the World, 20 April 2006

V AFGHANISTAN

US Dollar Smooths Rugged Way Over the Old Silk Road, 3 October 2001

Into Afghanistan’s Heart, 13 October 2001

Smoking Hash While the US Bombs Fall, 17 October 2001

No Peace While There Are Foreign Hands, 27 October 2001

Trapped in a War That Every Afghan Dreams of Escaping, 31 October 2001

VI IRAQ

Clear Memories of Dark Days, 15 March 2008

Baghdad Under the Bombs, 2 April 2003

‘Yours, guiltily’, 8 April 2003

On the Last Day of Saddam’s Misrule, 10 April 2003

Surreal Scenes as Marines Have Their Big Day, 10 April 2003

Saddam’s Regime is Toppled, 10 April 2003

Distressed Iraqis Exhume Their War Dead, 23 April 2003

Unspeakable Savagery on the Streets of Baghdad, 10 October 2003

The Ghastly Results of a ‘Licence to Kill’, 8 April 2004

When the Danger for Journalists is Omnipresent, 20 October 2005

Saddam Shows Old Power as he Defies Judges, 20 October 2005

Misery of Life Beyond the Green Zone, 22 October 2005

Kill the Dictator, 1 January 2007

Old Grievances, 20 May 2008

VII ISRAEL & PALESTINE

‘We are living in cages’, 4 April 2000

France Puts on Ceremony Worthy of a Head of State, 12 November 2004

Massacre in Munich, 21 January 2006

Palestinians Being Punished for Choosing Hamas, 8 April 2006

Israel’s Calling Card, 23 January 2009

Inside the World’s Biggest Prison, 24 January 2009

‘We hope our sacrifice will be the last …’, 31 January 2009

US and EU Must Impose Solution to Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, 3 February 2009

VIII THE UNITED STATES

America’s Irrational Streak Runs Deep, 18 September 2004

Old Interview Gives New Insights into America’s First Couple, 12 January 2009

Following in Lincoln’s Footsteps, 21 January 2009

Edward Kennedy, ‘the kind and tender hero’, is Laid to Rest, 31 August 2009

Homeless on the Capitol’s Doorstep, 21 November 2009

When Reality of Afghan War Strikes Home, 1 December 2009

US Just Doesn’t ‘Get It’ about Motivation for Suicide Attacks, 13 January 2010

First the Storm, Now the Spill, 8 May 2010

Rogue Sheriff Investigated, 11 June 2010

IX HAITI

‘We dug for five hours … we no longer heard him’, 16 January 2010

The Agony of Faimi Lamy, 19 January 2010

The Salvation of Faimi Lamy, 6 July 2010

Aftershock, 21 January 2010

Catholicism and Voodoo: Rival Faiths, 26 January 2010

Whims of the West Will Shape Future for Haiti, 28 January 2010

EPILOUGE: FURRY Friends

Walter the Beirut Puss, 7 June 2000

An Irish Cat in Paris, 11 July 2001

Paris–Washington, 8 September 2009

In Praise of Cats, 22 June 2010

Index

Copyright

‘There is such a thing as truth and it can be told.’

– Seamus Heaney

(to Dennis O’Driscoll in Stepping Stones, Faber and Faber)

Acknowledgements

Journalism is a lifelong apprenticeship. Though it’s usually a matter of trial and error, and especially a school of hard knocks, colleagues and editors have taught me a great deal.

I am grateful to The Irish Times for underwriting my reporting for the past fourteen years, and for giving permission for my articles to be reproduced in this book. There’s a special place in my heart for Paul Gillespie, the Irish Times’ retired foreign policy editor, who hired me and most of my generation of foreign correspondents.

I’ve had five fine foreign editors at The Irish Times. Over the years, they have been the umbilical cord that tied me to the paper, providing moral support, guidance and a degree of freedom that few publications grant their journalists.

In January 1988, Patrick Comerford commissioned ‘Going West in Beirut’, the first article I published in The Irish Times; it is reproduced in this book.

At my request, Seamus Martin sent me to Afghanistan after the atrocities of September 11, with the blessing of then editor Conor Brady.

Also at my request, the paper’s current editor, Geraldine Kennedy, allowed me to cover the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and to return to the country repeatedly thereafter.

When he was foreign editor, Peter Murtagh saw me through NATO’s bombardment of Serbia in 1999, the Iraq war, and Lebanon in the wake of Rafik al-Hariri’s assassination.

Paddy Smyth sent me to cover the Israel-Hizballah war in 2006, the Georgian war two summers later, and the aftermath of Israel’s January 2009 assault on the Gaza Strip.

In my present post as Washington correspondent, I have benefited from Denis Staunton’s vast knowledge of the US. With his rapid, infallible news sense, Denis dispatched me to Haiti to cover the earthquake, to Louisiana for the oil spill, and to Arizona for the battle over immigration.

For my first thirteen years at The Irish Times, Paris was my bread and butter. My foreign editors, but also editors from other sections, particularly Patsey Murphy in the Weekend section, and later the Saturday Magazine, received my copy with enthusiasm.

There is a terrific sense of collegiality on The Irish Times, and I’ve been encouraged and helped by secretaries, switchboard operators, copy-takers, sub-editors, computer technicians and accountants too numerous to name.

Long ago, the television producer Barry Lando gave me my first break in journalism when he hired me as a researcher-associate producer for CBS News’ 60 Minutes programme. Barry and I did some great stories together. On one of them, in Damascus in 1983, I met Robert Fisk, to whom I was married for twelve years. Robert was, malgré tout, the best journalism teacher.

Unless otherwise stated, all articles which appear in this collection were originally published in The Irish Times.

Preface:A Life in Journalism

On a spring morning in 1981, I handed over a coin at the kiosk on the avenue Hoche, picked up a copy of the International Herald Tribune and turned to the back page. There was a photograph of Alain Robbe-Grillet, the ‘father of the nouveau roman’, whom I had just interviewed. I didn’t know then that sub-editors, not reporters, write headlines. The title on the article was different from the one I had thought up before posting my copy to Neuilly. The bastards, I thought; they ran an article by somebody else.

Then my eyes fell to the byline, where I read, for the first time ever in a daily newspaper: ‘by Lara Marlowe’. I yelped for joy, leapt in the air and ran around in circles. My life as a journalist had started.

I wrote another article, another and another. Some were rejected. There were setbacks. Nearly three decades and several thousand articles later, I am still pleased to see my byline.

I turned thirty, then forty, then fifty. Middle age did not creep up on me; it jumped out and said ‘boo’. But two filing cabinet drawers full of articles were proof of the passage of time. They confirmed the breadth of my French experience, chronicled eight years in Beirut, recounted nearly a decade of blood letting in Algeria. From the siege of Sarajevo to NATO’s punishing bombardment of Serbia, I had seen the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Without my realising it, my life fell into neat, historic segments. France and Ireland were my home base and refuge, and I often found their footprints in the regions where I travelled. But Lebanon, Algeria and Yugoslavia dominated the 1990s; Afghanistan, Iraq and the United States the first decade of the new century. I watched the Americans bomb Kabul, then Baghdad. ‘Vietraqistan’, as the American journalist Mort Rosenblum calls it, was the recurring theme of the noughties.

Much of my work was done from the safety of Paris. But without ever intending to be a war correspondent, I reported from frontlines in Central America, the Horn of Africa, the Caucasus and, especially, the Middle East and Iraq. The wars I covered, big and small, short and long, added up to some fifteen conflicts, depending how you counted.

Among the images that swarm through my mind is a narrow, monastic room in a retirement home in Bourj Hammoud, the Armenian quarter of Beirut. An icon of the Virgin hangs between two beds, in which lie a husband and wife, aged one hundred and five and ninety-seven respectively. Both are blind. They listen to Radio Yerevan in their waking hours. The old man bears a scar on one cheek, etched by a sabre at the Battle of Tannenberg, where he fought on the side of the Tsar’s army in 1914. The following year, when the Turks began the first genocide of the twentieth century, he made the long march to what was then Mesopotamia, and across the desert to Lebanon, where he met his wife.

Had his life been happy, I asked him. ‘I hate my circumstances now,’ he said. ‘But the things I have seen, no one has seen.’

I once asked my dear friend the French academician Michel Déon whether I should write fiction or non-fiction. ‘Anyone can write a novel,’ Michel replied. ‘You have seen things no one else has.’

Writing novels remains the mirage that tantalises one through the slog of daily journalism. Yet I have loved this profession as one loves a place or a person. No adventure matches that paring down of belongings to a single suitcase and heading for the airport. Journalism, I realise now, has given me a far more pungent taste of life than any ivory tower.

Indeed, journalism has given me many lives. Each time I have moved on to a different country or conflict, the world has seemed new. And every time I have escaped a close call, I’ve wondered whether, like the cats who have been my companions, I am exhausting my nine lives.

In my reporting, I strive for authenticity: to freeze the fleetingness of time, to preserve people and situations in all their intensity. It is a paradox, for ours is a transient medium. As a French colleague liked to remind me, newspapers are meant to wrap fish the next day.

Like the proverbial fisherman, some of my best stories ‘got away’. I searched fruitlessly through archives and old diskettes for three articles that fell victim to last minute confusion, rivalry among editors, and the dictates of political correctness at TIME Magazine, which employed me for eight years.

I loved the story of the Kuwaiti newspaper editor Faisal al-Marzouk, because it had a happy ending. On the day Iraqi forces fled Kuwait City in February 1991, a wealthy woman pleaded with me to find her brother, who had been taken to Basra by the Iraqis, along with hundreds of Kuwaiti civilians. Eventually, in the middle of a cold night on the Iraq–Kuwait frontier, I stuck my head into a dozen coaches filled with newly released prisoners. In each one I shouted: ‘Is Faisal al-Marzouk here?’

From the photographs I had seen, I would not have recognised the grimy, dishevelled man who fell into my arms, weeping, when I told him: ‘Faisal, I am a friend of Salwa, Jassem and Siham. They asked me to look for you. They are waiting for you.’

In 1994, I worked for weeks on a story slugged ‘Tale of Two Cities’, about Beirut recovering from civil war, just as Algiers plunged into darkness. I wrote thousands of words on the Arab capitals, but a dream recounted by Aliya Saïd, an upper middle class Beirut matron, taught me that wars never end for those who lose loved ones. Aliya’s late husband, Rafik, had come to her in her sleep a few nights before, and said: ‘Hurry up, Aliya. Get ready. We are going to see Fouad.’

The Saïds’ son had been killed years earlier, in crossfire between Kurdish factions near Beirut’s ‘green line’. Rafik died of grief. Aliya lived like a zombie, playing bridge and holding dinner parties, trying to fill the void where her family had been. Eventually her liver gave out, destroyed by the amphetamines and tranquillisers she took to get up in the morning and sleep at night.

Another story, the text of which I have also lost, was entitled ‘Family Saga’. It recounted the history of a Palestinian family who had been scattered by the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. Some clung to their native Galilee; others fled to Lebanon and Jordan. My editors at TIME thought that the problems of this Palestinian family should be solved by the 1993 Oslo Accords. When that turned out not to be the case, they lost interest. But I shall never forget Abu Ahmad, the patriarch of the Amman branch of the family, seated at a table in his prosperous restaurant, burying his head in his hands when he spoke of his childhood village, saying: ‘Mirun, Mirun, I cannot forget you.’

I visited Mirun with Abu Ahmad’s Arab-Israeli cousins. Their family’s graceful stone houses had been transformed into a Yeshiva, for the study of Jewish sacred texts. I spoke in French with one of the inhabitants, a Talmudic scholar who had emigrated from Morocco. As the Palestinians hung back, fearing confrontation, I asked the Jewish man from Morocco what had happened to Mirun’s Arab inhabitants. ‘There were never any Arabs here,’ he said curtly, ending our conversation.

Suffering is the lot of mankind; if my reporting sometimes strikes a chord in readers, I believe it is because I feel tied to the people whose pain I describe. As T. S. Eliot wrote: ‘I am moved by … The notion of some infinitely gentle/Infinitely suffering thing.’ Some, like the parents of children who died violently in Ireland and France, became friends. Most have been swallowed up by distance and time. But I do not forget them.

There is Leila Behbehani, the three year old Iranian girl whose body I saw in a cold storage warehouse in Bandar Abbas, one of 290 civilians killed when the USS Vincennes guided missile cruiser shot down an Iranian airliner in 1988. Leila was on her way to a wedding, and was wearing a turquoise party dress. She died with the contorted face of a child who is crying. Captain Will Rogers III, the commander of the Vincennes, was given a medal.

There is the woman in the smouldering, blood spattered ruins of UNIFIL’s Fidjian Battalion headquarters in Qana, southern Lebanon, on 18 April 1996, less than an hour after Israel had bombarded the post, killing 106 Lebanese civilians. She squats on the ground, her arms laced around her father’s torso, rocking on her ankles and sobbing ‘Abi, abi’ (‘My father, my father’). He cannot hear her, for his body has been cleaved diagonally by a proximity shell.

Nothing happens in isolation. Sometimes the link is obvious. The cancellation of elections won by Islamists in Algeria precipitated years of bloodshed. I still believe that the Lockerbie bombing was retaliation for the downing of the Iran Air flight six months earlier. And although it is heresy to say so, when al-Qaeda murdered close to three thousand people in the atrocities of September 11, 2001, I sensed immediately that it was connected to the slaughter of Muslims in Lebanon and Bosnia, to the festering wound of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

When I covered the Haitian earthquake in January 2010, I was surprised at the worry expressed by friends and colleagues. They seemed to think I would be traumatised by so much death and destruction. It was far easier than a war, I told them. No one was trying to kidnap or kill me. But most of all, one did not feel the rage that comes from seeing innocents die under bombardment.

In all the wars I covered, the Geneva Conventions were regarded as a quaint museum piece, at best. In 1999, the US and NATO blurred the line between civilian and military targets by bombing a passenger train, power plants, telephone exchanges, the Serb radio-television building – even the Chinese embassy in Belgrade. Time and again, the US military has killed civilians: when they shot down the Iranian Airbus, bombed Albanian refugees in Kosovo, shelled journalists in the Palestine Hotel in Baghdad, and carried out drone attacks in Afghanistan and Pakistan. As long as it’s an ‘accident’, the Americans seem to think it’s okay.

The Israelis learned the lesson well, testing the ‘Dahiya doctrine’ (named after the Shia Muslim southern suburbs of Beirut) in Lebanon, where they killed 1,287 people in the summer of 2006. Under this doctrine, no distinction is made between civilian and military targets – as demonstrated horrifically in Israel’s January 2009 assault on Gaza, in which 1,434 Palestinians were slaughtered.

The words ‘international community’ make me nauseous, for they have come to embody inaction, indifference and hypocrisy. It was the ‘international community’ that allowed the siege of Sarajevo to continue for almost four years, during which Serb gunners picked off ten thousand people like ducks. The same ‘international community’ makes empty promises about lifting the siege of Gaza, about rebuilding Gaza and Haiti. If Barack Obama has a shred of idealism left in him, he must forge an international community that respects the lives of civilians and keeps its word.

I have learned simple things: that governments lie; that, as Benjamin Franklin wrote, ‘there never was a good war or a bad peace’. I have learned to appreciate my own good fortune, having seen how little stability, security or well-being exists outside the fortresses of our developed countries.

At the Féile an Phobail in west Belfast the summer of 2010, I was asked if I despaired of what the American poet e. e. cummings called ‘manunkind’. I didn’t want to sound negative, and strained to find examples of heroism. On occasion, I have encountered humour, generosity, altruism, even beauty. But for the most part, I have found the world to be as Matthew Arnold described it: without joy, love, light, certitude, peace, or help for pain. The instruments of suffering are usually remote: fighter bombers at altitudes of tens of thousands of feet; the secret minutes of politicians’ meetings. Only occasionally does one glimpse the face of cruelty: in a Serb prison camp commander or, more recently, in an Arizona sheriff who glories in chain gangs of hungry prisoners and the deportation of Mexican migrants.

Despite the sadness and anger, I remain endlessly fascinated by the human condition. I still want to know what will happen. Looking back at this juncture, this mezzo camino, I have found something approaching a meaning and a purpose: to be there, to see, and to record.

Howth, County Dublin August 2010

I

FRANCE

Douce France

City of My Life

I started to love Paris when I was a schoolgirl in California. My widowed mother returned from a tour with her church group carrying a blue plastic Air France shoulder bag, stuffed with film rolls and trinkets. Her souvenirs from Egypt, Rome, London and the New York World’s Fair did not interest me. But the silk scarves and perfume, a little brass Eiffel Tower and her snapshots of the Place de la Concorde, the Arc de Triomphe and Notre Dame filled me with premonitory excitement.

In the summer of 1976, I emerged from the Concorde métro station with a rucksack on my back, after flying all night in a charter to Le Bourget. A quarter of a century later, the sense of wonderment is still fresh. There before me were the Obelisk, the Champs-Élysées, the Eiffel Tower, the Seine, the Tuileries Gardens. Growing up, I had almost come to doubt its reality; arriving in Paris as a student was like finding proof that paradise existed.

Four times I packed my belongings and departed, only to return within a few years. Most of my triumphs and disasters, friendships and romances, have taken place in this city. There is scarcely a street or monument that does not hold some personal memory. But Paris also speaks to me of kings and princesses, Jacobins, Communards and characters in novels. Who can pass the Louvre without remembering Louis XIV and François Mitterrand? When I cross a Paris bridge at night, I think of the Camus character throwing herself into the Seine in The Fall. The Pont Mirabeau will always remind me of Apollinaire’s unrequited love for Marie Laurencin.

Could there be a richer place to live? To hear Parisians say they find Rome or Prague more beautiful always strikes me as betrayal. In its favour, they will tell you that Paris is built on a human scale, and it’s true; despite the monuments scattered across the capital, it’s never daunting. Unlike most cities, Paris is small enough to be manageable. I’ve never needed a car here, and allowing for métro changes, you can reach any appointment in forty-five minutes.

It’s also possible to enjoy life in Paris without a lot of money, though why a loaf of bread, a flask of wine and a book of verse suffice here but not in London or New York I have never fathomed. My favourite picnic spot is the left bank of the Seine, at the end of the rue des Saints-Pères. The view of the Louvre is free, but take cushions to sit on because the stones are cold and hard.

Every Parisian loves his or her quartier. I know a few people who swear by the right bank, but in my opinion there is nothing to compare with the 6th arrondissement, where I’ve lived for the past five years. My best days start with a run through the Luxembourg Gardens. The central vista from Marie de Medici’s palace (now the French Senate) and down the avenue de l’Observatoire is as spectacular as anything at Versailles.

But I like the meandering, English-style paths on the western side of the Luxembourg, where you round a corner to find a herd of French firemen stampeding towards you, a woman wearing make-up and jewellery with her designer tracksuit, or lonesome old people walking ridiculous dogs. You hear the ‘thunk, thunk’ of tennis balls on clay courts, and squeals of joy from children liberated from stuffy apartments to sail toy boats on the ornamental pond. Busts and statues nestle among exotic bushes and flowering trees, and it’s fun to see that Baudelaire, Sainte-Beuve or Stendahl look like the Frenchman you’ve just interviewed. Crowds form around chess matches under the trees on Sundays, when Parisians wearing sunglasses lean their chairs against the arboretum walls to read books and newspapers or snooze.

The cobblestoned rue Ferou is the quickest way from the Luxembourg to the Place Saint-Sulpice. I owe a new appreciation of the church, originally built to keep the peasants out of nearby Saint-Germain, to the former French hostage Jean-Paul Kauffmann. He wrote a best-selling book about Saint-Sulpice, centred on Delacroix’s magnificent fresco of jacob and the Angel, just inside the front door to the right. Even if I rarely go in, the painting has lodged in my imagination, like Napoleon’s candle-lit banquet for six hundred in the church nave, or the sculptress of angels whom Kauffmann found living under the roof.

A true Parisian has his or her canteen, and I found mine years ago. The Cherche-Midi is an old-fashioned bistro, with naif wall murals of men playing boules, railway carriage benches and bent wood chairs. Hugues Masson, the maître d’, knows I like table nine in the corner in winter, and any table on the pavement under the red canvas awning in summer. The olive bread is home-made, like the pasta dishes, which change every day. Carafes of house red are called fillettes or ‘little girls’. The menu is basic southern French or Italian, the ambiance noisy and cheerful.

Muriel Spark wrote a poem called ‘The Dark Music of the Rue du Cherche-Midi’, which sums up the charm of my street. The poem begins: ‘If you should ask me, is there a street of Europe, and where, and what, is that ultimate street?’

The long, long rue du Cherche-Midi, she answers. In her poetic catalogue, Spark somehow missed number seventeen, where the Duc de Saint-Simon wrote his memoirs. The eighteenth century house at number forty, across the street from my hairdresser, is marked by a plaque as the place where the Comte de Rochambeau planned his 1780 expedition to help American revolutionaries.

Spark’s description of my street holds true for all of Paris: ‘Suppose that I looked for the street of my life,/ where I always/ could find an analogy. There in the/ shop-front windows and in the courtyards,/ the alleys, the great doorways, old convents, baronial/ properties:/ those of the past.’

But the rue du Cherche-Midi is also a sad street, haunted by the military prison where Dreyfus stood trial and where Resistance heroes were tortured by the Nazis. Knowing that I’m about to move half a mile away, a friend gave me a recently published book by Catherine Clément, in which the French novelist recounts growing up in the rue du Cherche-Midi during the Second World War.

I hadn’t realised that the ugly block between the rue Dupin and the rue Saint-Placide replaced a building that was bombed by the Germans. When the war ended, Clément waited with her mother Rivka outside the Hotel Lutetia every day for her Jewish grandparents, George and Sipa, but they never came back from Auschwitz. What transformations Paris goes through; the Lutetia was a headquarters for the German military intelligence service, the Abwehr, then a reception centre for concentration camp survivors. Now it’s a five-star hotel where you sometimes find Isabelle Adjani, Emanuelle Béart or Yasmina Reza giving interviews in the bar.

A few days ago, I was walking with an old friend, the writer Olivier Todd. It was twilight, and Olivier pointed to four windows lit up on the corner of the rue Bonaparte and the rue Apollinaire, opposite the church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, ‘That was Sartre’s mother’s flat,’ he said. ‘I used to go there to see him. He slept in that room, which was the library.’ Olivier went into La Hune bookshop to browse. I bought Le Monde and headed home, savouring this magic – another Paris treasure to be stashed away in one’s mind.

14 July 2001

For two decades French governments have talked about decentralising France. They’ve passed law after law, poured money into regional councils. To no avail: France will always be Paris.

Balzac understood the irresistible pull of the capital. It is, he wrote, ‘a city that swallows up gifted individuals born everywhere in the kingdom, makes them part of its strange population and dries out the intellectual capacities of the nation for its own benefit. The provinces themselves are responsible for the force that plunders them …. And as soon as a merchant has amassed a fortune, he thinks only of taking it to Paris, the city that thus comes to epitomise all of France.’

I’ve already lived three lives here: as a student at the Sorbonne in the late 1970s, as a struggling freelancer in the early 1980s and as an Irish Timescorrespondent since 1996. Over the years, friends and professional contacts from my three epochs have melded.

Though I remain a foreigner, I know this city better than any other: the way it begins to stir, later than other capitals, around 8 AM, the crush of the métro in rush hour, the priceless silence of Sunday. Nothing, in the twenty-eight years since I first set eyes on Paris, has broken its spell over me.

The ponderousness of French bureaucracy can make Paris a frustrating city to work in, but the surroundings make up for it. When I read this quote from Zola in Alistair Horne’s wonderful Seven Ages of Paris: Portrait of a City, I wished I had written it myself: ‘I love the horizons of this big city with all my heart …. Depending on whether a ray of sunshine brightens Paris, or a dull sky lets it dream, it resembles a joyful and melancholy poem. This is art, all around us. A living art, an art still unknown.’

To live in Paris is a constant journey between past and present. There are countless personal memories, of a student garret and the flats one has rented, of meals in restaurants and the dresses you fell in love with through shop windows.

Some of the associations are incongruous: the Ranelagh métro station reminds me of the Monets in the Musée Marmottan and the Afghan embassy, where I picked up a visa after the atrocities of September 11, 2001. The Palais de Justice makes me think of Marie Antoinette, awaiting execution in the Conciergerie, and the endless hours I spent there during the investigation into the death of Diana, Princess of Wales.

Paris seems to heighten one’s moods and intuitions, but it also brings you closer to history. I’ve liked the somewhat garish Pont Alexandre III even more since Mitterrand had its statues of winged horses covered with gold leaf. When I interviewed the Russian-born writer Andrei Makine, I read his account of the inauguration of the bridge, in 1900, in the presence of the ill-fated Tsar Nicholas. Now I imagine Nicholas spreading mortar with a golden trowel and the poet José Maria de Heredia haranguing the imperial couple with his ode to Franco-Russian friendship.

Most of my mental landmarks in Paris are literary or artistic. There is a building down the street with a plaque saying Proust spent evenings there with his friends the Daudet brothers. When I walk past, if I’m not concentrating on my next newspaper article, I imagine Marcel wearing evening clothes with other young men around a table in a poorly lit, wood-panelled room.

The building I live in was built in 1880. It was a time when the arts flourished, when Monet, Manet and Renoir would meet to discuss painting. Though they tended to live in the 8th and 9th arrondissements across the river, I like to think that Impressionist painters – Monet himself? – once sat in my salon.

Baron Haussmann (who called himself a demolition artist) ordained that Paris should be a nineteenth century city. Though many regret the razed, winding streets of earlier centuries, the Haussmannian apartment buildings, with their moulded stucco ceilings, marble fireplaces and modern plumbing, were a revolution in living standards and remain comfortable today. Gustave Caillebotte’s painting of workmen scraping a parquet floor captures their grace.

Several times a year, the French festoon all government buildings with red, white and blue tricolours. Though they are celebrating the end of the First World War, or the Second World War, or Bastille Day, you’re tempted to take the flags as personal encouragement, the way the poet Apollinaire did on 13 July 1909, when he concluded in a poem: ‘They put out the flags in Paris because my friend André Salmon is getting married.’ Some of the most moving documentary footage I have ever seen, a surprising amount of it in colour, shows French and US troops arriving in Paris in August 1944.

Apollinaire, the first great French poet of the twentieth century, survived the trenches of the First World War only to be killed by the Spanish flu. There’s a plaque on the building where he died on the boulevard St Germain. Apollinaire was not a native Parisian – in fact, neither of his parents was French – but he proved yet again Balzac’s maxim that the capital swallows up all that is best in the country.

Apollinaire’s ‘Zone’ is to the French language what T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ is to English. On the night before he is to be guillotined, a convict relives his life, walking in his imagination through the streets of Paris. I’ve long intended to use ‘Zone’ as a sort of guidebook for an all-night promenade across the city.

‘You read the handbills the catalogues the singing posters/ So much for poetry this morning and the prose is in the papers’, says Beckett’s translation of ‘Zone’. At my newspaper kiosk in the morning, I often think of ‘the prose in the papers’. I used to watch the old green and white Berliet buses hurtle down the boulevards and recall Apollinaire: ‘Now you walk in Paris alone among the crowd/ Herds of bellowing buses hemming you about/ Anguish of love parching you within/ As though you were never to be loved again.’

I recently found a notebook that I had filled with poems and quotations when I went back to UCLA after my year at the Sorbonne. I didn’t know then that I would return to Paris, and this text by Camus reflected my nostalgia: ‘Paris is far away, Paris is beautiful; I have not forgotten her. I remember her twilights …. The evening falls, rustling and dry, over the rooftops blue with smoke; the city rumbles dully, the river seems to reverse its course. I wandered then in the streets.’

Whenever I can, I walk in Paris at sunset. The light, especially on long summer evenings, is incomparable. Paris still seems to rumble, but at its heart the Seine flows silently, the city’s soul, splendidly indifferent.

2 August 2004

A Last Farewell

A perceptive Irish friend noticed that this article was more than a tribute to Monsieur Castro. Mingled with my grief at his passing was sadness at having left Paris for Washington. As Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote: ‘It is Margaret you mourn for.’

The rue de Bellechasse is sad, because Jose Castro is dead. Monsieur Castro was no relation to the Cuban lider massimo, nor was he one of the public figures I wrote about as this newspaper’s France correspondent. His widow, Otilia, is the concierge of the building where I lived from 2001 until 2009, and they are like family to me.

Though Madame Castro held the official title of gardienne, the couple were a priceless ‘twofer’, a husband-and-wife team who shared the vacuuming, mopping and polishing. Together they knew every nook and cranny of the 130-year-old apartment building. They were its longest residents, having moved into the shoebox-sized loge in the 1970s. Their sons, Bernard and Jose, grew up in the loge and attended school nearby in the rue Las Cases.

For eight years, Madame Castro’s smile brightened my mornings. Monsieur Castro left early for his job as the head of a maintenance team at Roissy Charles-de-Gaulle Airport. Most days, he took a passenger in his little white lorry, a distinguished lawyer from the first floor of the building, whom he dropped off in the seventeenth arrondissement. Working at my desk in the afternoons, I’d hear cheerful chatter as Monsieur Castro’s small granddaughters, Luisa and Noémie, followed him around the building.

When public transport strikes sowed traffic chaos and I had a plane to catch, Monsieur Castro drove me to Roissy. Over the years, he fixed my leaking kitchen sink and my oven door, rigged a lamp for my piano music, sawed off the top of a too tall Christmas tree. He took pride in the small thing well done. When I travelled, Madame Castro looked after my cat, who adored her. The Castros were fundamentally good, and I trusted them completely.

On Friday afternoon, as I prepared to head back to Washington at the end of my spring holiday, Monsieur and Madame Castro were watching television when a massive heart attack killed him in seconds. ‘He left me,’ she repeated to me incredulously. ‘He didn’t deserve this.’ Now, like myself and tens of thousands of would-be travellers, the Castros are stranded in Paris by the Icelandic volcano. Monsieur Castro’s casket waits in a funeral home for flights to resume, so he can be buried in his beloved Galicia.

After queuing at Air France for four hours on Saturday to rebook my own flight, I asked if there was anything the airline could do to ensure that Monsieur Castro’s remains are repatriated quickly. ‘Everybody has problems,’ an Air France agent snapped. ‘We can’t make exceptions.’ But this is a bereavement, I protested. ‘Not even for bereavements,’ she answered.

The Castros were a throwback to another time, when immigrants came from Catholic countries, and no Parisian apartment block survived without a concierge. Young men and women met at dances, courted, married, had children and stayed together.

Jose met Otilia at the Bataclan dance hall in Paris’s Oberkampf district on Christmas Eve 1973. She worked as a cleaner in a doctor’s clinic. He washed windows for a living. Both hailed from Galicia, north-western Spain; he from the mountain, she from the plain, eighty kilometres apart. At age twenty-five, Otilia was considered an old maid. Jose was three years her senior. It was, she said through her tears, un vrai coup de foudre, love at first sight. For more than thirty-six years, they were never apart.

Though their sons have dual nationality, the Castros remained Spanish. ‘He said we had to be proud of our origins,’ Madame Castro explained. The couple spent every August in Galicia, and refurbished an old stone house there for their retirement. The last time I saw Monsieur Castro alive, twenty-four hours before his heart attack, he grinned when he showed me the leather folder containing his pension papers. ‘I am going to retire in June,’ he announced.

The day after Monsieur Castro died, Madame Castro put on a clean apron, wheeled the rubbish bins in through the cobblestone entry, hung laundry in the back courtyard. ‘If I don’t work, I’ll go crazy,’ she said. ‘The children want me to sleep at their house, but I want to stay here, with our good memories …. A few minutes before my husband died, we were laughing. I said, “Papie, we’re getting old now; two granddaughters and a third on the way.” He said, “Yes, Mamie, we must start thinking of ourselves soon.”’

19 April 2010

La France de Sarkozy

Nicolas Sarkozy’sVictoire Extraordinaire

‘C’est extraordinaire!’ is Nicolas Sarkozy’s favourite expression. He uses it most often to describe real or imagined criticism of himself, as in: ‘When I talk about the nation, I’m accused of being a nationalist. When I talk about immigration, I’m accused of being a racist. When I talk about patriotism, I’m accused of being a fascist. C’est quand-même extraordinaire!’

Whatever one thinks of Sarkozy, you’ve got to hand it to him: his victory in the French presidential election may not have been a surprise, but it was nothing short of extraordinaire: the real-life culmination of a Hollywood screenplay entitled The Fabulous Destiny of nicolas Sarkozy.

Roll the clocks back a few years. Bernadette Chirac, the outgoing first lady who was allegedly gifted with infallible political judgment, told her entourage that Sarkozy would never become president of France. He was too short, too foreign-looking and had no provincial roots – hitherto a requirement for every French leader.

Nothing predisposed Sarkozy to becoming the sixth president of the Fifth Republic. As the extreme right-wing leader Jean-Marie Le Pen ungraciously reminded France during the campaign, three out of four of Sarkozy’s grandparents were foreign.

On his father’s side, he is descended from minor Hungarian aristocracy; his father, Pal Nagy Bosca y Sarkozy, used to tell him: ‘With a name like yours, you’ll never get anywhere in France.’ His maternal grandfather, who raised him, was Benedict Mallah, a wealthy Jew from Salonica.

Sarkozy failed the entrance exam to ‘Sciences Po’ because his English wasn’t up to scratch. Unlike the failed socialist candidate Ségolène Royal – and most of the country’s political elite – he did not attend the École Nationale d’Administration. That was probably a blessing.

Taunting the socialist benches of the National Assembly, Sarkozy once said: ‘You don’t talk like the people do; that is why you lost them.’ Sarkozy’s directness may be his greatest advantage. Time and again, voters have told me they liked him ‘because they understand what he says’.

The French are also fascinated by Sarkozy’s thirst for power; if he wants it so badly, he must deserve it. There’s a good dose of revenge in Sarkozy’s ambition.

‘je vais les niquer tous’ (‘I’m going to screw them all’), a fellow journalist once heard Sarkozy mutter repeatedly during a helicopter journey.

Despite Sarkozy’s outsider status, there now seems to have been a certain inevitability to his rise. Within months of joining the Raffarin government as interior minister in 2002, he became the most popular member of the cabinet.

Action – or at least the media semblance thereof – was the secret to his success. Tony Blair’s government was furious with France for allowing thousands of Kurds and Afghans to pour across the English Channel? Sarkozy closed the camp at Sangatte. French lorry drivers threatened an umpteenth strike? Sarkozy broke the strike in one day, by threatening to confiscate their licences.

When the former prime minister Alain Juppé founded the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) in November 2002, Sarkozy insisted that Juppé be given a two-rather than three-year mandate as leader. Was he already plotting his own takeover of the party?

He and his wife Cecilia refused the seats reserved for them in the second row at the launch, ostentatiously placing themselves front and centre. A year later, Sarkozy announced that he intended to succeed President Jacques Chirac.

There followed a battle of Shakespearean, or perhaps Oedipal, proportions, with Sarkozy constantly vaunting his superiority over Chirac. The president’s rule was ‘a house of cards’ on the verge of collapse, Sarkozy told the 237 right-wing deputies he invited to dinner shortly before Bastille Day 2004.

Chirac made a last attempt to call the unwanted upstart heir to order. ‘I take decisions; he executes them,’ Chirac told the nation in his annual televised interview.

Having provoked Chirac, Sarkozy then adopted the same strategy he would use during the campaign against Royal: he played the poised statesman who refuses to respond to aggression. Against the better judgment of his closest advisers, including his wife, Sarkozy resigned from his post as finance minister to stand for president of the UMP.

Commentators widely compared his 28 November 2004 ‘coronation’ as head of the party to Napoleon Bonaparte’s lavish consecration almost exactly two hundred years earlier. Napoleon-like, Sarkozy spoke of his ‘grand design’. Unlike Royal, who asked voters what they wanted, Sarkozy told them what they needed.

The losing socialist candidate accused Sarkozy of ‘brutalising’ France. She failed to understand that the country may be at a stage where it wants to be ‘brutalised’. Sarkozy promises to share his energy, determination and confidence with the country, as if by transfusion.

The outline of Sarkozy’s presidential programme was already present in his November 2004 acceptance speech: the rehabilitation of work, revision of the thirty-five-hour week and the welfare system, and the abolition of death duties, so the French can pass on ‘an inheritance built by the sweat of the brow’.

When Sarkozy finds himself out of sync with the French mood, he never publicly changes policy. He opposed the law banning the wearing of Islamic headscarves in French schools, but shut up when he saw how popular it was. He proposed US-style affirmative action to integrate French minorities, but stopped talking about it when it raised hackles. His condemnation of French ‘arrogance’ in opposing the invasion of Iraq went down badly, so during the campaign he repeated that the US had made a grave error.

France’s new president is a man of paradoxes. The son and grandson of immigrants, he takes pride in having expelled a record numbers of would-be immigrants from France. He is a tough crime-buster who yearns to be loved; a short man who once scratched out his height on his driver’s licence, and mysteriously appeared to be the same height as George W. Bush (who is some fifteen centimetres taller) on the retouched photograph of their meeting. The self-styled ‘spokesman of the people’ is fascinated by pop stars, celebrities and millionaires.

The reactions of two acquaintances this weekend seemed to summarise national schizophrenia about Sarkozy. An elderly woman who holds dual French and Irish nationality told me: ‘I can’t help liking that young fellow – he’s so un-French!’ She even romanticised the ‘look of sadness’ she always detects in his eyes.

A neighbour in central Paris, a businessman whose company trades in Asia, told me he’d go early to the polls, then leave the country until the celebrations blow over. ‘I can’t stand the thought of France being in Sarkozy’s hands for the next five years,’ he said. ‘He and his gang are mafiosi. I don’t want to hear and see the sarkozystes gloating.’

The country that Nicolas Sarkozy is about to take over is a land of hope and fear. Will he teach the French the merits of hard work, and usher in prosperity and full employment by the end of his five-year term, as promised? Or will he cow the press – a process that has already started – inflame race relations, pit rich against poor, and preside over war on the immigrant banlieues? These possible outcomes, positive and negative, are part of the Sarkozy paradox. And they are not mutually exclusive.

7 May 2007

Europe Gets Set for the Sarkozy Treatment

President Nicolas Sarkozy’s armchair was strategically placed in the door of the Élysée Palace, so the air conditioning from the Petit Salon wafted over him. It was the hottest day of summer so far, and the French leader pulled his jacket off while two of his top advisers, jackets on, sweated in the scorching sun beside him.

A servant brought the president’s mirror shades, the ones that accentuate his resemblance to a mafia don. Sarkozy was receiving several dozen European correspondents for a background briefing on France’s EU presidency on his terrace.

He pulled an ankle over one knee, and the raised leg jerked with nervous energy. His Highness asked for more umbrellas to shade the journalists. The other leg too started jiggling. Microphone in hand, like a pop star, Sarkozy jumped up and launched into the Sarko show.

For an hour and a half, in the noon sun, Sarkozy cajoled, seduced and belittled his interlocutors. The short sentences were direct, unambiguous and frequently punctuated by ‘hein,’ an inelegant interjection signifying something approximating ‘N’est-ce pas?’

‘I do the questions and the answers,’ Sarkozy boasted at one point in the monologue. He does not tolerate criticism, and those of us who dared ask impertinent questions bore the full brunt of his sarcasm.

My colleagues from Brussels were fascinated and repelled by the Sarko show. ‘I kept thinking about the dinosaurs on the European stage,’ one said. ‘No other European leader has Sarko’s energy or ability to hold people’s attention. The thing that struck me most was the naked aggression of it; the way he stood and leaned over us ….’

Aggression is a word one hears often in connection with Sarkozy. In the past week alone, the chief of staff of the French army, a journalist and a technician at France 3 television, the head of France Télévisions, the president of the European Central Bank, the EU trade commissioner and French trade unions have all been victims of presidential wrath or sarcasm.

These incidents bring to mind earlier presidential faux pas – like the hostile bystander to whom Sarkozy said ‘Get lost, asshole’ at the agriculture fair last winter. He’s widely accused of ‘desecrating’ the presidential office, though others say he’s dusted off a fossilised institution.

As Sarkozy’s confidence rating again descended to an abysmal 33 percent last week (it was 63 percent when he was elected in May 2007), it was obvious that the president’s attitude is irritating his compatriots. ‘I’ve rarely seen anyone who shows such disdain for his fellow human beings,’ says Alain Genestar, the former editor of Paris Match, who was sacked for publishing a cover showing Sarkozy’s second wife, Cecilia, in New York with the man whom she would later marry.

Immediately after his divorce, Sarkozy’s courtship and remarriage, to the top model-turned-singer Carla Bruni, shocked conservative voters and precipitated his plunge in opinion polls last winter. Though Bruni was initially a handicap, the couple’s state visit to London in late March changed that. Carla’s class seems to compensate for Nicolas’s rough edges. ‘She calms the president down,’ aides at the Élysée keep insisting.

Sarkozy seems as agitated as ever, but Bruni took credit for attenuating his ‘bling-bling’ reputation. Her new album has received rave reviews despite lyrics comparing the ‘high’ she gets from Sarkozy to drugs, and an admission that she has had ‘thirty lovers in forty years’. A poll in L’Express magazine shows that 51 percent of the French think Bruni is a good First Lady. When a correspondent asked whether she would accompany the president to Dublin on 21 July, a French diplomat joked: ‘You voted No [to the Lisbon Treaty]. If you vote Yes next time, then you get Carla.’ In the wake of Ireland’s rejection of the treaty, Sarkozy announced that he would travel to Dublin in an effort to understand the No vote. He has already postponed the trip once, and will spend half a day in Ireland. ‘What do you expect?’ an official said. ‘He’s a man in a hurry. It has to fit into his schedule.’ With French newspapers translating the Fine Gael MEP Gay Mitchell’s comment that ‘the last thing’ Ireland needs is for Sarkozy to come ‘riding into town’, the French president might even cancel his visit.

Though Sarkozy has long abandoned his advocacy of a directoire of the six most populous countries (France, Germany, Britain, Spain, Italy and Poland) to run Europe, it’s hard to shake the impression that he respects only the powerful, in particular les Anglo-Saxons. In a telling detail at his reception for foreign ambassadors last August, there was free seating for all, except the US and British ambassadors, whose front row, centre seats were reserved.

‘France is back in Europe,’ Sarkozy announced on the night of his election. Within weeks, he had unilaterally vetoed negotiations on questions pertaining to full Turkish EU membership, resumed his crusade against the European Central Bank and announced that France would not respect the Eurogroup’s stability pact (on reducing deficits) before 2012. As black sheep of the fifteen-strong Eurogroup, France is second only to Greece. Yet on the eve of the EU presidency, the French president promised lower taxes on ‘ecological’ cars and houses, restaurants, CDs and DVDs.

Diplomats and officials describe Sarkozy as impatient and incapable of listening – characteristics that will not help him resolve Ireland’s rejection of the treaty. In an e-mail leaked in April, an Irish official wrote that the referendum was being held before the French presidency because of ‘the risk of unhelpful developments during the French presidency, particularly related to EU defence’ and called Sarkozy ‘completely unpredictable’.

On Saturday night, I attended a dinner party in the 16th arrondissement, a few blocks from Carla Bruni’s house. All the guests had voted for Sarkozy. They were delighted when he became the first president to put women and minorities in positions of power. But now they’re disappointed; all criticised his ‘aggressiveness’ and ‘vulgarity’ but said they saw no alternative to him.

Though there were disappointing aspects to his reform of the régimes spéciaux (public-sector pensions), the university system and thirty-five-hour working week, the dinner guests credited Sarkozy with being the first French president to ‘take on’ such special interest groups as transport workers. His law on economic modernization will free up competition and raise the retirement age to sixty-one.

A former left-wing cabinet minister later told me that the socialists want Sarkozy to stay in power long enough to ‘do the dirty work’ of economic reform, which they dare not undertake themselves, so they can breeze back into power when the pain is over.

With the EU presidency, Sarkozy’s image as a personally unpleasant but extremely energetic, if sometimes arbitrary, reformer has been projected on to the European scene. ‘I am president of France. I am president of Europe,’ he boasted at the weekend.

France has developed a love-hate relationship with ‘Sarko’, in which belief in the necessity of economic reform mingles with fear of the president’s erratic, autocratic ways. Sarkozy doesn’t like sharing the limelight, but there are steady hands – French Prime Minister François Fillon, German chancellor Angela Merkel – to reassure us.

For at least four more years, Sarkozy is the only show in France. In Europe, there are only five and three-quarter months left to go.

8 July 2008

Why Obama and Sarkozy Can Never Truly Be Friends

The presidents stood at twin lecterns in the East Room of the White House. They could not have looked more mismatched, but they professed near-identical views. Both want the UN Security Council to pass tough sanctions against Iran, quickly. Both want Israel to stop colonising the West Bank. And both say that winning in Afghanistan is crucial to the security of the West.

‘Rarely in the history of our two countries has the community of views been so identical between the United States of America and France,’ President Nicolas Sarkozy crowed.

How could two men espousing the same policies convey such different impressions? The healthcare victory has put a new spring into Barack Obama’s step, even if his opinion poll results lack bounce. Sarkozy’s party has just lost regional elections, and his approval rating is at an all time low of 30 percent.

Sarkozy appeared tense and distracted throughout their twenty-two-minute press conference. While Obama spoke, Sarkozy’s eyes darted about the reception room, as if he expected someone to lob a grenade at him. When Sarkozy spoke, Obama turned politely towards him and listened.

Sarkozy related the most telling anecdote. In what looked like another act of Obama-mimicry, Sarkozy had taken his wife, Carla Bruni, to Ben’s Chili Bowl for lunch. (In January 2009, Obama lunched at the U Street diner with Washington mayor Adrian Fenty.) ‘When I walked in, I saw a huge photograph of President Obama,’ Sarkozy said. ‘And I’m afraid that when you go back to that restaurant, you may see a smaller photograph of the French president.’

Sarkozy was vain enough to bestow his picture upon a Washington restaurant, in the hope that it would hang beside Obama’s.

No other head of state has been invited, with his wife, to dine à quatre with Barack and Michelle in their private dining room, the Élysée kept saying. Sarkozy needed Obama to burnish his image.

And strange as it may seem, the world’s most popular politician, the star whom other heads of state and government vie to befriend – indeed serve – has been faulted for having no buddies among world leaders. Obama has tried to circumvent governments, to reach out directly to world populations. But his domestic critics say that his global populism is hurting US interests.

At the White House press briefing on the day of Sarkozy’s visit, the questions were more informative than the answers. Was the White House trying to ‘make up with the French president’, a correspondent asked. Robert Gibbs, the press secretary, feigned ignorance. ‘There have been perceptions that there was a snub, that [Sarkozy] didn’t get quite the treatment that he thought he should get in their prior visits together,’ the journalist explained.

Sarkozy is often his own worst enemy. At Columbia University, he commented on the healthcare bill, saying: ‘We solved the problem fifty years ago …. Welcome to the club of states that don’t dump sick people.’

‘He said it in French, but you could hear the smirk,’ commented Chris Matthews of MSNBC television.

Sarkozy also told the US that it needed to ‘reflect on what it means to be the world’s number one power’ and to be a country ‘that listens’. The New York Times told him to stop lecturing, and to send more troops to Afghanistan.

Despite the intimate dinner, you couldn’t help but notice that the White House did the bare minimum. Dinner started at 6.30 and lasted less than two hours. There were no photographers allowed in the Oval Office during the bilateral meeting – a courtesy accorded to more honoured guests.

Obama has befriended leaders, just not the Europeans traditionally cosseted by US presidents. He’s reserved his warmest hospitality for the Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh, who enjoyed the first state dinner of the Obama presidency, and Taoiseach Brian Cowen, guest of honour at the White House St Patrick’s Day reception for five hundred guests. On these occasions, Obama mentioned the ‘oppression’ endured by the US, India and Ireland. The adjective ‘British’ was understood.

Therein, I suspect, lies the biggest difference between Sarkozy’s and Obama’s world views. Before Sarkozy became president, his UMP party attempted to pass a law requiring French schools to teach ‘the positive role’ of French colonialism.

Three times in twenty-two minutes, Sarkozy mentioned the transatlantic directorate formed by himself, Angela Merkel, Gordon Brown and Barack Obama. Obama looked uneasy.

Each time Obama is perceived to snub a former colonial power, I recall the passage in Dreams from my Father where the future US president imagined the experiences of his grandfather, Hussein Onyango, who worked as a servant to British officers in Kenya. ‘He still hears the clipped voice of a British captain, explaining for the third and last time the correct proportion of tonic to gin.’

Sarkozy hero-worships les Anglo-Saxons. One of Obama’s first acts as president was to send a bronze bust of Winston Churchill (which George W. Bush had borrowed for the Oval Office) back to the British ambassador.