11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

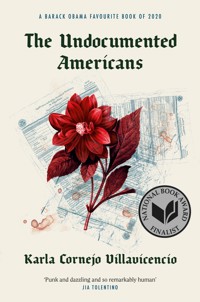

A BARACK OBAMA FAVOURITE BOOK OF 2020 A New York Times best book of 2020 One of the first undocumented immigrants to graduate from Harvard reveals the hidden lives of her fellow undocumented Americans. Right after the election of 2016, Karla Cornejo Villavicencio realized the story she'd tried to steer clear of was the only one she wanted to tell. So she wrote her immigration lawyer's phone number on her hand and embarked on a trip across the country to tell the stories of her fellow undocumented immigrants – and to find the hidden key to her own. In her incandescent, relentlessly probing voice, Karla Cornejo Villavicencio combines sensitive reporting and powerful personal narratives to bring to light remarkable stories of resilience, madness, and death. She finds the singular, effervescent characters across the nation often reduced in the media to political pawns or nameless laborers. The stories she tells are not deferential or naively inspirational but show the love, magic, heartbreak, insanity, and vulgarity that infuse the day-to-day lives of her subjects. And through it all we see the author grappling with the biggest questions of love, duty, family, and survival. Shortlisted for a National Book Award, a National Book Critics' Circle Award and an L.A. Times Book Prize

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 287

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Swift Press

First published in the United States of America by Penguin Random House 2020 First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2021

The Undocumented Americans is a work of non-fiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright © Karla Cornejo Villavicencio 2020

The right of Karla Cornejo Villavicencio to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Book design by Caroline Cunningham

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-80075-039-5 eISBN: 978-1-80075-040-1

Chinga la Migra

A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his own image.

—Joan Didion, The White Album

In memory of Claudia Goméz Gonzáles

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1: Staten Island

CHAPTER 2: Ground Zero

CHAPTER 3: Miami

CHAPTER 4: Flint

CHAPTER 5: Cleveland

CHAPTER 6: New Haven

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

INTRODUCTION

On the night of the 2016 presidential election, I spent a long time deciding what to wear. I’d be staying home to watch the returns with my partner, but the Comey letter had come out in mid- October and I was convinced Trump was going to win. I’d always admired the women on the Titanic who reportedly drowned wearing their finest clothing and furs and jewels and the violinists who kept playing even as the ship sank. I wore a burgundy velvet dress with sheer lace back paneling, a ribbon in my hair, red lipstick, and a leopard-print faux fur coat over my shoulders. I poured myself a goblet of wine. I understood that night would be my end, but I would not be ushered to an internment camp in sweatpants. The returns hadn’t finished coming in when my father, who is undocumented, called me to tell me it was the end times. I threw myself into bed without washing off my makeup, without brushing my teeth. I had a four a.m. wake-up call.

A few hours later, I took a bunch of trains to New Jersey to meet an oceanographer I was profiling for a New York magazine. We took a boat into the Hudson and sped by the feet of the Statue of Liberty. “Fuck,” I said. “This will appear sentimental.” Still, I asked him to take my picture in front of it, and I smiled at the camera, the strong winds blowing my hair in my face.

It seemed safe, somehow, to be there, at Lady Liberty’s feet. I got off the boat and, on my phone, emailed an agent I’d been friendly with since I was a kid and told him I was ready to write the book. The book. And he said okay.

The book. When I was a senior at Harvard, I wrote an anonymous essay for The Daily Beast about what they wanted to call “my dirty little secret”—that I was undocumented. It got me some attention—it was a different time—and agents wrote asking me if I wanted to write a memoir. A news program asked to film me while I fucking packed up my dorm, to show, I guess, that I was leaving Harvard without any plans, without even the promise of a career, which was the crux of my essay.

This was before DACA.

I was angry. A memoir? I was twenty-one. I wasn’t fucking Barbra Streisand. I had been writing professionally since I was fifteen, but only about music—I wanted to be the guy in High Fidelity—and I didn’t want my first book to be a rueful tale about being a sickly Victorian orphan with tuberculosis who didn’t have a Social Security number, which is what the agents all wanted. The guy who eventually ended up becoming my agent respected that, did not find an interchangeable immigrant to publish a sad book, read everything I would write over the next seven years, and we kept in touch. I was the first person who wrote him on the morning of November 9, 2016.

That morning, I received a bunch of emails from people who were really freaked out about Trump winning and the emails essentially were offers to hide me in their second houses in Vermont or the woods somewhere, or stay in their basements. “Shit,” I told my partner. “They’re trying to Anne Frank me.” By this point, I had been pursuing a PhD at Yale because I needed the health insurance and had read lots of books about migrants and I hated a good number of the texts. I couldn’t see my family in them, because I saw my parents as more than laborers, as more than sufferers or dreamers. I thought I could write something better, something that rang true. And I thought that I was the best person to do it. I was just crazy enough. Because if you’re going to write a book about undocumented immigrants in America, the story, the full story, you have to be a little bit crazy. And you certainly can’t be enamored by America, not still. That disqualifies you.

This book is not a traditional nonfiction book. Names of persons have all been changed. Names of places have all been changed. Physical descriptions have all been changed. Or have they? I took notes by hand during interviews; after the legal review, I destroyed the notes. I chose not to use a recorder because I did not want to intimidate my subjects. Children of immigrants whose parents do not speak English learn how to interpret very young, and I honored that rite of passage and skill by translating the interviews on the spot. I approached translating the way a literary translator would approach translating a poem, not the way someone would approach translating a business letter. I hate the way journalists translate the words of Spanish speakers in their stories. They transliterate, and make us sound dumb, like we all have a first-grade vocabulary. I found my subjects to be warm, funny, dry, evasive, philosophical, weird, annoying, etc., and I tried to convey that tone in the translations.

When you are an undocumented immigrant with undocumented family, writing about undocumented immigrants—and I can only speak for myself and my ghosts—it feels unethical to put on the drag of a journalist. It is also painful to focus on the art, but impossible to process the world as anything but art. The slightest gust of the wind bruises—Trump’s voice, Stephen Miller’s face, the red hat, but also before that, the deli counter, the construction corner, the hotel room, the dishwashing station, the dollar store, the late-night English classes at the local community college—and it’s a pain I am sure is felt by the eleven million undocumented, so I write as if it were. I attempt to write from a place of shared trauma, shared memories, shared pain. This is a snapshot in time, a high-energy imaging of trauma brain.

This book is a work of creative nonfiction, rooted in careful reporting, translated as poetry, shared by chosen family, and sometimes hard to read. Maybe you won’t like it. I didn’t write it for you to like it. And I did not set out to write anything inspirational, which is why there are no stories of DREAMers. They are commendable young people, and I truly owe them my life, but they occupy outsize attention in our politics. I wanted to tell the stories of people who work as day laborers, housekeepers, construction workers, dog walkers, deliverymen, people who don’t inspire hashtags or T-shirts, but I wanted to learn about them as the weirdos we all are outside of our jobs.

This book is for everybody who wants to step away from the buzzwords in immigration, the talking heads, the kids in graduation caps and gowns, and read about the people underground. Not heroes. Randoms. People. Characters.

This book is for young immigrants and children of immigrants. I want them to read this book and feel what I imagine young people must have felt when they heard Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” for the first time in Seattle in 1991. I grew up a Jehovah’s Witness, and I remember what I felt listening to “Smells Like Teen Spirit” for the first time.

I went into the bathroom and chopped off my hair with my mom’s fabric scissors and then messaged a boy who was not a Jehovah’s Witness (not allowed) and told him to meet me at the Virgin Megastore in Times Square to give me my first kiss. This book will give you permission to let go. This book will give you permission to be free. This book will move you to be punk, when you need to be punk; y hermanxs, it’s time to fuck some shit up.

Karla Cornejo Villavicenio

CHAPTER 1

Staten Island

AUGUST 1, 2019

If you ask my mother where she’s from, she’s 100 percent going to say she’s from the Kingdom of God, because she does not like to say that she’s from Ecuador, Ecuador being one of the few South American countries that has not especially outdone itself on the international stage—magical realism basically skipped over it, as did the military dictatorship craze of the 1970s and 1980s, plus there are no world-famous Ecuadorians to speak of other than the fool who housed Julian Assange at the embassy in London (the president) and Christina Aguilera’s father, who was a domestic abuser. If you ask my father where he is from, he will definitely say Ecuador because he is sentimental about the country for reasons he’s working out in therapy. But if you push them, I mean really push them, they’re both going to say they’re from New York. If you ask them if they feel American because you’re a little narc who wants to prove your blood runs red, white, and blue, they’re going to say No, we feel like New Yorkers. We really do, too. My family has lived in Brooklyn and Queens a combined ninety-seven years. My dad drove a cab back when East New York was still gang country, and he had to fold his body into a little origami swan and hide under his steering wheel during cross fires in the middle of the day while he ate a jumbo slice of pizza. Times have changed but my parents haven’t. My dad sees struggling bodegas and he says they’re fronts. For what? Money laundering. For whom? The mob. My mother wants my brother and me to wear pastels all year round to avoid being seen as taking sides in the little tiff between the Bloods and the Crips.

My parents are New Yorkers to the core. Despite how close we are, we’ve talked very little about their first days in New York or about their decision to choose New York, or even the United States, as a destination. It’s not that I haven’t asked my parents why they came to the United States. It’s that the answer isn’t as morally satisfying as most people’s answers are—a decapitated family member, famine—and I never press them for more details because I don’t want to apply pressure on a bruise.

The story as far as I know it goes something like this: My parents had just gotten married in Cotopaxi, Ecuador, and their small autobody business was not doing well. Then my dad got into a car crash where he broke his jaw, and they had to borrow money from my father’s family, who are bad, greedy people. The idea of coming to America to work for a year to make just enough money to pay off the debt came up and it seemed like a good idea. My father’s family asked to keep me, eighteen months old at the time, as collateral. And that’s what my parents did. That’s about as much as I know.

You may be wondering why my parents agreed to leave me as an economic assurance, but the truth is I have not had this conversation with them. I’ve never thought about it enough to ask. The whole truth is that if I was a young mother—if I was me as a young mother, unparented, ambitious, at my sexual prime—I think I would be thrilled to leave my child for “exactly a year,” as they said it would be, which is what the plan was. I never had to forgive my mom.

My dad? My dadmydadmydad was my earliest memory. He was dressed in a powder-blue sweater. He was walking into a big airplane. I looked out from a window and my dad was walking away and, in my hand, I carried a Ziploc bag full of coins. I don’t know. It’s been almost thirty years. It doesn’t matter anymore.

My parents didn’t come back after a year. They didn’t stay in America because they were making so much money that they became greedy. They were barely making ends meet. Years passed. When I was four years old, going to school in Ecuador, teachers began to comment on how gifted I was. My parents knew Ecuador was not the place for a gifted girl—the gender politics were too fucked up—and they wanted me to have all the educational opportunities they hadn’t had. So that’s when they brought me to New York to enroll me in Catholic school, but no matter how hard they both worked to make tuition, they fell short. Then one day—I think I was in the fourth grade—the school bursar called me into his office and explained that there was an elderly billionairess who lived in upstate New York who had heard about me and was impressed. He told her my family was poor and might have to pull me from the school. (Okay, so in this scenario the tragedy would have been that I’d have to go to the local public school, which was not a great school, but just so we’re on the same page, I support public schools and I would have been fine.) So she came up with a proposition. She’d pay for most of my tuition if I kept up my grades and wrote her letters.

That was the first time in my life I’d have a benefactor, but it would not be my last. When I was at Harvard, a very successful Wall Street man who knew me from an educational NGO we both belonged to—he as a supporter, me as a supported—learned I was undocumented and could not legally hold a workstudy job, so every semester he wrote me a modest check. In the notes section he cheekily wrote “beer money”—the joke being that I wouldn’t really drink until I was twenty-one—but every semester I used it for books, winter coats for those fucking Boston winters, money I couldn’t ask my parents for because they didn’t have any to give. I wrote him regular emails about my life at Harvard and my budding success as a published writer. He was always appropriate and boundaried. I had read obsessively about artists since I was a kid and considered myself an artist since I was a kid so I didn’t feel weird about older, wealthy white people giving me money in exchange for grades or writing. It was patronage. They were Gertrude Stein and I was a young Hemingway. I was Van Gogh, crazy and broken. I truly did not have any racial anxieties about this, thank god. That kind of thing could really fuck a kid up.

I’m a New York City kid, but although the first five years of my time in America were spent in Brooklyn, if we’re going to be real, I’m from Queens. Queens is the most diverse borough in the city. This might sound like a romanticized ghetto painting, but when I walk through my neighborhood, a Polish child with a toy gun will shoot at my head and say the same undecipherable word over and over; a Puerto Rican kid will rap along to a song on his phone and turn it up as loud as necessary to make out the lyrics, even rapping along to some N- words; some Egyptian teenagers will refuse to move out of my way as I’m simply trying to cross the street; and some Mexican guys will invite me to join a pyramid scheme. But none of us will try to take any rights away from one another. We don’t have potlucks, but we live in peace. We go to the same street fairs.

The other boroughs are less diverse, but I found that the same thing is basically true. Except for one borough that I was always curious about—Staten Island, New York’s richest, whitest, most suburban borough. It is almost 80 percent white. By way of comparison, Brooklyn and Queens are just less than half white, the Bronx is 45 percent white, and even Manhattan is only 65 percent white. Staten Island is geographically isolated—you can’t take the subway there from the city—and, I don’t know, man, there isn’t a lot of shared goodwill between islanders and city residents. It’s not like we’re unaware. They’ve literally tried to secede from New York City and form their own city or join New Jersey. In June 1989, the New York State legislature gave Staten Island residents the right to decide on secession, and in November 1993, 65 percent of voters voted yes. Governor Mario Cuomo insisted that the referendum be approved by the state legislature, where it was defeated, but the desire continued to bubble just beneath the surface for years, so even after the world was rocked by Brexit, you had local island politicians posting on social media about how inspiring an event it was. Staten Island is the city’s most conservative borough, pretty reliably Republican, the only borough in New York City to go for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election. It’s also the borough where Eric Garner was killed in a choke hold at the hands of NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo. A Staten Island grand jury declined to indict Pantaleo for murder.

I learned about all of this later. But the first time Staten Island really entered my consciousness was when there were news reports about hate crimes against Latinx people when I was a kid. This was the only context in which Staten Island was mentioned on Spanish nightly news—Mexican immigrants as victims of hate crimes at the hands of young black men, a cruel reminder of the rift between our communities. There was fifty-two-year-old Alejandro Galindo, who was walking his bicycle home from his dishwashing job and was attacked by four men who didn’t take anything. There was eighteen-year-old Christian Vázquez, who was attacked by five men as he was coming home from his job as a busboy. They beat him and took jewelry and a measly ten dollars from him as they yelled anti-Mexican slurs. There was twenty-six-year-old Rodolfo Olmedo, jumped by four men on his way back from a club. They beat him with a baseball bat, a metal chain, and wooden planks. “We believe at this time that they selected this victim either in whole or in substantial part because he was a Mexican,” Richmond County district attorney Daniel Donovan said.

I headed to Staten Island to report on the lives of undocumented day laborers in early 2017—it was close to where I lived in New Haven, and I was terrified about Trump having just assumed office. I was scared for all immigrants and felt guilty about myself as a so-called DREAMer. I was on DACA and I was afraid there’d be a raid. I was afraid that in any situation where there were large groups of undocumented people congregated, there could be a raid. My first trip there, I took a taxi from the Newark train station, about a thirty-minute drive, to the neighborhood of Silver View, home to one of the oldest day laborer corners in New York City. I got carsick, so I closed my eyes and filled the time with a mental rosary chain of short prayers to god, out of whose favor I had fallen years ago. I rested my head on the window and asked him to protect my family first, and if he had some goodwill left over, I prayed that there wouldn’t be a raid on the warehouse where I was going that night.

Before visiting Staten Island, I’d never met a day laborer. To me, a city girl who knew undocumented men mostly as restaurant workers, day laborers seemed like an almost mythical archetype, groups of brown men huddled at the crack of dawn on street corners next to truck rental lots and hardware superstores and lumberyards. Historically, legislators and immigration advocates have parted the sea of the undocumented with a splintered staff—working brown men and women on one side and academically achieving young brown people on the other, one a parasitic blight, the other heroic dreamers. Day laborers weren’t real to me, and what I had heard about them wasn’t good. The New York Times described their work as “idling on street corners.” They haven’t had the best PR.

So who are they? There are varied estimates of the number of day laborers in New York City, from a little under six thousand to more than ten thousand. A 2006 survey of day laborers, who are mostly men, reports that 75 percent of respondents identified as undocumented, two-thirds supported their families with this line of work, 60 percent said day laboring was their first job in the United States, and 85 percent were looking for more permanent jobs. They represent a wide range of skills, from muscle to flooring to woodwork to welding to painting to cement work to brickwork to carpentry to insulation to stucco to electrical work to just about everything else in the construction universe.

The typical place they find work is the street corner, where a delicate choreography takes place. One guy told me the exchange goes something like this: A man pulls up in a truck and says, I need X done. If a person has that skill, he’ll ask for a quote—how many hours, in what location, how much per hour. Sometimes while you are negotiating, two other workers willing to do the job for less jump into the truck and the employer shrugs and drives away. Sometimes a group piles onto the sides of the truck, and the employer gets spooked. They don’t know us. It’s the group that scares them. If they’re scared, they might hastily pick one or two guys, or they might drive away. An average of sixty workers gathers on each of the known street corners in Silver View every day. On a quiet day there might be three workers, on a busy day a hundred. They mostly get paid in cash, and the employers are free to do with and to them whatever they want.

The day laborers I meet are professionals, talking about the importance of negotiating rates and building networks through good work and recommendations. They call their employers patrones, a Spanish word that means “bosses” but with a colonial aftertaste, often do not get protective equipment, meal breaks, or even bathroom breaks. They have all experienced racist abuse and wage theft at the hand of their employers, are all owed thousands of dollars by white men who made them work for days, promised payment, then simply disappeared. Some days laborers are dropped off at remote locations to do work, then left there without a ride back, unpaid and helpless. The fact that The New York Times described them as “idling” infuriates me. What an offensive way to describe labor that requires standing in hellish heat or cold or rain from dawn until nightfall, negotiating in a language not your own, competing with your own friends for the same job, then performing it to perfection without the certainty of pay. Workers absorb exceptional emotional and physical stress every day and, because they are undocumented, they’re on their own, with no workplace protections, no regulations, and no collective bargaining.

This is where the worker centers come in. Worker centers were established to formalize this very informal sector of day laboring. There are now more than sixty-three worker centers across the country. Colectiva Por Fin is a storefront nonprofit on Staten Island that since 1997 has provided practical advocacy, representation, and training for day laborers and the immigrant community on the island at large. It sits on Silver View Road along with Nuestra Calle, another worker center, right near the busy street corners where day laborers generally congregate, and they make a world of difference for the men. First, they are indoors, so the men don’t have to stand outside for hours on end in extreme weather. The centers provide restrooms, water, coffee, phone chargers, and dispatchers. Dispatchers serve as bilingual intermediaries between workers and employers, cementing transactions and preventing abuses or irregularities. It’s a stressful job.

Santiago, a dispatcher at Colectiva Por Fin, is a U.S. citizen born to Mexican parents. Workers collectively set the rates for particular jobs annually or semiannually, and Santiago’s job is to make sure those rates are honored and workers aren’t drawn into potentially abusive arrangements. “Some employers think that exploiting them might be easy because they are undocumented,” he tells me. Santiago is just twenty-five years old.

I’m attending a monthly meeting at Colectiva Por Fin on my first night on Staten Island. The room is small but as more men come in, it seems to double and triple in size. On the wall, migrants are celebrated through art that strikes me as deeply annoying, mostly the word “migrant” reconfigured as butterflies. I fucking hate thinking of migrants as butterflies. Butterflies can’t fuck a bitch up. Tonight, about fifty men end up gathering in the room, plus a couple of women, including a young, white female pastor who works for Project Hospitality, the parent nonprofit. The executive director of Colectiva Por Fin is here, an Argentine man named Simón Torres. He is new and the men are still making up their minds about him. There are two African American day laborers at the meeting and an older white man with a shock of white hair and mustache. His name is Charles and he is here as an organizer from AmeriCorps. Because of these three people, the meeting is conducted bilingually by Santiago, effectively cutting the meeting shorter while making it feel longer at the same time. Out of the fifty Latinx workers, perhaps only a few are able to ascertain the fidelity of Santiago’s translation.

The men here tonight are workers. For many years when I have heard nice people try to be respectful about describing undocumented people, I’ve heard them call us “undocumented workers” as a euphemism, as if there was something uncouth about being just an undocumented person standing with your hands clasped together or at your sides. I almost wish they’d called us something rude like “crazy fuckin’ Mexicans” because that’s acknowledging something about us beyond our usefulness—we’re crazy, we’re Mexican, we’re clearly unwanted!—but to describe all of us, men, women, children, locally Instagram-famous teens, queer puppeteers, all of us, as workers in order to make us palatable, my god. We were brown bodies made to labor, faces pixelated.

And here they are now, the workers. Some are very young, just past their teens, and some are quite old, around seventy. They are all wearing dirty work boots, but carefully kept. You know how jeans come pre-ripped? That’s how their boots look. Dirty from work, pristine from care. The workers are very brown, brown from their moms, browned from the sun. They are short. But they are built. They look like they can walk on burning coal, build a house, and open a bottle of beer with their wedding rings.

When I scan the room, I see men lighter and darker than my father, some older, most younger—they speak harsher, softer, mumbling, or sung, but I see my father’s face in their every one, and I know that this astigmatism will always be with me; the light will always fall this way. I think about the 2010 Arizona immigration law known as the Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act, a.k.a. Arizona SB 1070, a.k.a. the “papers please” law. It gave law enforcement officials the power to approach anybody they suspected of being in the country illegally and ask for proof of legal documentation. That meant they could stop anyone they thought looked undocumented. Immigrant rights advocates furiously protested the law, challenging officials on how exactly they defined an “undocumented look.” But Vincent, my best friend from college, and I, two undocumented kids, whispered to each other that even if the authorities “couldn’t,” we could pretty much almost always tell. The backpack my father carried on his commute to and from work, the one that held his earnings in cash, was a red flag. His black rubber orthopedic-looking shoes and his dark-blue jeans, immigrant-blue, an immigrant rinse. I offered to buy him new clothes but he said, Para que? Vincent offered to buy his dad a change of clothes for when he traveled home from his construction job but his dad said, Para que? too.

Santiago is an accomplished and artful translator. He works quickly and in real time and transmits tone impeccably. Charles from AmeriCorps gives a long-winded speech inviting the men to an upcoming church dinner. He keeps mentioning the president’s name. In his translation, Santiago omits every mention of Trump. Charles says the dinner will feature American fare—“You’re going to get to try American food; I promise you’ll love it.” That sentence too disappears in our young dispatcher’s hands. Charles ends his speech by saying, “If things get worse, and I really, really don’t think they will, Americans will come out and protect you.” Santiago doesn’t translate any of that either. He’s pretty fucking good.

I ask Santiago where he learned to translate so well and he tells me that like many children of immigrants, he grew up interpreting for his parents at everything from PTA meetings to doctors’ appointments. “It made me feel important,” he says. “I was representing my parents.” I tell Santiago I did the same thing, that we all did. I ask him why he omitted all mentions of Trump in the speech. “I didn’t want to mention that guy,” he says. “I wanted to make them feel safe.”

I ask why he completely omitted Charles’s promise to protect them if things got bad.

“The reality is . . . it’s not just Trump. Staten Island is a very conservative island. Charles might think it’s not getting worse, but he is not going to be affected, unless they stop federal funding of his organization, and then he could lose his job. But the whole immigrant community has everything to lose.”

But what about the guarantee that Americans would come to our rescue? I ask.

“Unless these Americans are lawyers or federal judges, I don’t see how that’s true,” Santiago says.

A year and a half later, I’ve been to Staten Island so many times, I’ve lost count. I’ve grown attached to these men and look for any excuse to go back to learn more about the world the day laborers have created in the most anti-immigrant hood in the city. I’ve stood with them on street corners and sat with them in the worker centers, I’ve had coffee with them at Dunkin’ Donuts, ate lunches with them at Ecuadorian restaurants they insist on paying for, delivered dinners for them to share in the worker center office, I’ve accompanied them to testify in City Hall, attended their Christmas party where none of them asked me to dance, went to their soccer matches, and spoke to them on the phone late at night. We texted Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to one another one minute after midnight. I blocked one of them on my phone because his intense loneliness was dark and desperate and it scared me. Come a blizzard in Connecticut, where I live now, and I think of how thin the lining is in their jackets; when the season changes and the pavement gets so hot that I don’t walk my dog for longer than a few minutes out of concern for his soft padded feet, I think of how hot jetblack hair gets under the sun, like my brother’s, like my father’s, like mine. When I see acrylic blankets I think of them alone in their rented single rooms, and when my father visits me in my big apartment with all the natural light and big fiddle-leaf trees, I see them in his missing teeth and swollen hands. When my father lost his restaurant job of fifteen years, I asked one of my contacts from Colectiva if she knew of any jobs, and she said that he could go to the worker center at 7:00 a.m. to begin working as a day laborer. Imagine that. Day one as a day laborer, at age fifty-three.

Julián is fifty-two years old but looks much, much older. When I first meet him, he is sitting alone in the corner of the worker center wearing headphones as men wait for their assignments. His beanie is pulled over his eyebrows, covering the tops of his ears, actually almost half of his ears—he has small ears. Everyone else is talking and laughing. I ask him what he’s listening to and he says, “Christian music to uplift the spirits.” I persuade him to give me his number, but it takes a few conversations for him to open up. It’s clear he has spent a lot of time alone with his thoughts. Many of the day laborers don’t have family living with them on Staten Island and are lonely, so talking with me at the end of a long day from the tiny corners of their rooms is something they seem to like. With Julián, once he is ready, our conversations are like the opposite of bloodletting, the darker, thicker stuff coming out first, and then we work our way toward a light exchange about the weather before we hang up.

Julián didn’t know a word of English when he came to the United States. His first meal in America was a bag of potato chips and a fifty-cent bottle of water. Remember those? He had nothing. He started work as a dishwasher at a restaurant two days later. His bosses were despots. They screamed at him, they swore. They had a rule that no outside food was allowed in the kitchen, but the only food the workers were allowed from the kitchen were eggs and potatoes. The cook was Latinx, like them, and he snuck them meat—cuts of chicken and steak—when the bosses turned their backs. “Pinche pendejo,” the cook said.

The hours were long and pay was terrible, so he decided to give day laboring a try. On his first day, he was terrified. “I was scared to work because I did not know English,” he says. “The employers yelled at me because I didn’t. I would stand on the street corner with my friends, but because I was so scared, I sent them to do jobs that I was hired to do. I was scared that I could not speak English, and that in turn made me scared I could not do the job. But then I went to school.”