Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

On the night of 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler leaned out of a spotlit window of the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, bursting with joy. The moment seemed unbelievable, even to Hitler. After an improbable political journey that came close to faltering on many occasions, his march to power had finally succeeded. While the story of Hitler's rise has been told in books covering larger portions of his life, no previous work has focused on his eight-year climb to rule: 1925–1933. Renowned author Peter Ross Range brings this period back to startling life with a narrative history that describes brushes with power, quests for revenge, nonstop electioneering and underhand campaign tactics. For Hitler, moments of gloating triumph were followed by abject humiliation. This is the tale of a school dropout's climb from the infamy of a failed coup to Germany's highest office. It is a saga of personal growth and lavish living, a melodrama rife with love affairs and even suicide attempts. But it is also the definitive account of Hitler's unrelenting struggle for control over his raucous movement as he fought off challenges, built and bullied coalitions, quelled internecine feuds and neutralised his enemies – all culminating in the creation of the Third Reich and the world's descent into darkness. One of the most dramatic and important stories of the twentieth century, Hitler's ascent spans Germany's wobbly recovery from the First World War through years of growing prosperity and, finally, into crippling depression. Masterfully woven into an unforgettable and urgent narrative, The Unfathomable Ascent will remind us of what we should never forget.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 705

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO BY PETER ROSS RANGE

1924: The Year That Made Hitler

Front cover image: © Hulton Archive/Getty Images

First published in the US in 2020 by Little, Brown and Company

First published in the UK in 2020

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Peter Ross Range, 2020, 2022

The right of Peter Ross Range to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 555 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

ForFranklin and Caroline

CONTENTS

Timeline

List of Characters

A Note About Storm Troopers, Photographs, and Maps

Prologue

PART ONEREBIRTH AND REBUILDING(1925–1928)

1. Backstory

2. Resurrection

3. Wagner’s Ghost

4. Ebert to Hindenburg

5. Always on the Run

6.Mein Kampf

7. Bayreuth

8. Strasser and Goebbels

9. Bamberg Debacle

10. Brutal Willpower

11. Weimar Party Convention

12. Conquering the World

13. Falling in Love

14. Girding for Battle

15. Conquering Berlin

16. Impending Catastrophe

17.The Attack

18. Altering the Unalterable

19. Rock Bottom

PART TWORESET(1928–1929)

20. Hitler’s Second Book

21. Taking Stock

22. 1929

23. Alfred Hugenberg

24. Conquering Nuremberg

25. Cataclysm

PART THREETURNING POINT(1930–1931)

26. Fondness for Fighting

27. A Black Day

28. Two Months That Changed the World

29. Hitler on the Hustings

30. Turning Point

31. Hearts and Minds

32. Waiting for Hitler

33. Open Revolt

34. Hitler and Women

35. Geli

36. Hindenburg, Hugenberg, and Harzburg

37. Boxheim and the American Media

PART FOURGRASPING FOR POWER(1932)

38. A Floating Political Game

39. Running for President

40. Certain of Victory

41. Hitler over Germany

42. Groundswell

43. Intrigue and Betrayal

44. High-Water Mark

45. At the Gates of Power

46. Falling Comet

47. Secret Relationship

48. Eternal Intriguer

49. Crisis

PART FIVEENDGAME(1933)

50. New Year’s Reckoning

51. Assignation in Cologne

52. Impaling a Fly

53. Berlin Nights

54. Schleicher’s Fall

55. Unfathomable Ascent

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

A Note on Sources

Notes

Bibliography

TIMELINE

1889: Hitler is born in Braunau am Inn, Austria.

1908: Hitler moves to Vienna, Austria’s capital, where he fails the arts academy admissions exam. He falls on hard times, living in a homeless shelter for men.

1913: Dodging the Austrian draft, Hitler moves to Munich, Germany.

1914: Hitler enlists in the First World War, serving as a battlefield messenger.

1918: The war ends with Germany’s defeat. Revolution transforms the country from a monarchy into a democracy that becomes known as the Weimar Republic.

1919: Hitler joins the tiny German Workers’ Party in Munich.

1920–21: Hitler takes over the party, renaming it the National Socialist German Workers’ Party: the Nazi Party.

1923: Hitler attempts a coup d’état called the Beer Hall Putsch. It fails, and he is thrown in prison for more than a year.

1925: Released from prison, Hitler reestablishes the Nazi Party.

1928: In his first attempt at national politics, Hitler fails. The Nazi Party wins only 2.6 percent of the vote in a national parliamentary election.

1930: Hitler stuns Germany and the world by winning 18.3 percent of the national parliamentary vote, making the Nazi Party the country’s second-largest party.

1932: In early spring, Hitler runs for president against incumbent Paul von Hindenburg. Hindenburg is reelected, but Hitler captures 37 percent of the vote.

1932: In late April, the Nazi Party wins an average of 37 percent of the vote in a series of state elections involving 80 percent of the country’s voters.

1932: In July, Hitler again wins 37 percent of the vote in the year’s most important contest: the national parliamentary election. The Nazi Party is now uncontestably Germany’s strongest party.

1932: In November, the votes won by Hitler’s Nazis fall to 33 percent in yet another national parliamentary election. Though still the strongest party, the Nazis and their leader are considered to have peaked and to be in gradual decline.

1933: On January 4, Hitler’s fortunes are revived in a secret meeting with former chancellor Franz von Papen, who wants to use Hitler’s popularity for his revenge-seeking goal of becoming chancellor again.

1933: Throughout January, a series of secret meetings reverses the power constellation. Papen agrees to become vice-chancellor in a cabinet with Hitler as chancellor.

1933: On January 30, Hitler is made chancellor of Germany.

LIST OF CHARACTERS

Max Amann. Hitler’s company sergeant during the First World War, Amann later became head of the Nazi Party publishing enterprise, Franz Eher Nachfolger.

Edwin and Helene Bechstein. Heir to a piano-making fortune, Edwin supported his wife’s habit of donating funds to Hitler and hosting him at their villas in Berlin and Bayreuth.

Otto von Bismarck. A Prussian aristocrat and chancellor of Germany from 1871 to 1890, Bismarck is credited with achieving victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) and with uniting the fragmented German lands into a single country.

Eva Braun. A Munich shopgirl, Braun became Hitler’s girlfriend, mistress, and — just before their joint suicide, in 1945 — his wife.

Aristide Briand. A French prime minister and foreign minister, Briand formed a friendship with German foreign minister Gustav Stresemann. Briand, Stresemann, and Austen Chamberlain, the British foreign secretary, earned Nobel Peace Prizes.

Hugo and Elsa Bruckmann. A conservative Munich publisher, Hugo indulged his wife’s penchant for making financial gifts to Hitler and connecting him with influential people. Elsa advanced Hitler’s social standing by often inviting him to her weekly salon in the couple’s Munich mansion.

Heinrich Brüning. A technocratic financial expert and austere Roman Catholic, Brüning earned the nickname the Hunger Chancellor for his harsh deflationary policies as chancellor during the Depression.

Houston Stewart Chamberlain. A British-born political philosopher, Chamberlain became a German, married Richard Wagner’s daughter, Eva, and wrote (in German) a two-volume racist tome entitled The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century.

Bruno Czarnowski. A rabidly anti-Semitic Storm Trooper, Czarnowski created scurrilous slide shows for Hitler’s grassroots political campaigns.

Charles G. Dawes. A banker and US vice president under Calvin Coolidge, Dawes in 1923 led a commission to devise a viable reparations plan to help stabilize the turbulent German economy — the Dawes Plan.

Theodor Duesterberg. Duesterberg was a leader of the 250,000-strong Steel Helmet veterans’ association.

Friedrich Ebert. Weimar Germany’s first president, Ebert was a workingman who rose to the chairmanship of the Social Democratic Party (SPD).

Dietrich Eckart. Playwright, publisher, right-wing roué, and coffeehouse philosopher, Eckart held radical views on nationalism, Jews, and German destiny that profoundly influenced Hitler.

Hermann Esser. Esser was an early Nazi Party member who belonged to Hitler’s “Munich clique,” a group that relished beer-hall brawls and virulent anti-Semitism.

Hans Frank. Hitler’s lawyer and sometime confidant, Frank became governor-general of occupied Poland during the Third Reich. Sentenced to death during the Nuremberg trials, he hastily wrote a memoir that included his own wonderment at Hitler’s “unfathomable ascent.”

Wilhelm Frick. A lawyer and Munich police official, Frick was part of Hitler’s inner circle during the final climb to power. He became the head of the German internal security forces in Hitler’s government.

Joseph Goebbels. Riveted by Hitler’s forceful speeches, Goebbels dedicated his own propagandistic talents to boosting his leader’s political cause. As a near-daily diarist, Goebbels created a detailed insider’s account of Hitler’s ascent.

Hermann Göring. A First World War flying ace, the socially adept Göring joined the little Nazi Party in 1922. Badly wounded during the 1923 coup d’état, he fled Germany and became a morphine addict. In 1928, he returned to Germany and became part of Hitler’s brain trust.

Ernst Hanfstaengl. The scion of a wealthy German art book publishing family, Hanfstaengl grew up in Bavaria but went to college at Harvard, in the United States. In Munich, he traveled in high society and introduced Hitler to the city’s conservative elite. Especially well connected to the Anglo-American press, Hanfstaengl became Hitler’s walk-around pal and international press secretary.

Konrad Heiden. Heiden was a German journalist who chronicled Hitler’s rise from the beginning. Writing for the Frankfurter Zeitung and the Vossische Zeitung, he recognized Hitler’s unique emotional appeal early on but pronounced him “a falling comet” just weeks before he took power.

Heinrich Held. The governor of Bavaria, Held allowed reinstatement of the Nazi Party after Hitler was released from prison but imposed a speaking ban on the Nazi leader when he resorted to violent language. Held firmly opposed Hitler, alerting Germany’s leaders to his extreme leanings.

Rudolf Hess. Another well-born former pilot, Hess marched in the 1923 putsch attempt and spent six months with Hitler in prison. Upon release, he became Hitler’s private secretary and traveling associate. His letters to his fiancée and his parents are useful sources of details about the Nazi rise to power.

Heinrich Himmler. A trained agronomist, Himmler helped organize and discipline the Nazi Party. He played a key role in shaping Hitler’s successful 1930 election campaign and was appointed head of the SS (Schutzstaffel), a branch of the Storm Troopers.

Paul von Hindenburg. A First World War field marshal who vanquished the Russian army in 1914, Hindenburg was Germany’s most respected national hero. In 1925, he was elected the Weimar Republic’s second president. Reelected in 1932, he overcame his distaste for Hitler, the former foot soldier, and yielded to his advisers’ pleas that the Nazi leader be appointed chancellor in January of 1933.

Adolf Hitler. A nobody from nowhere, Hitler became Germany’s chancellor, dictator, and warlord. Born in 1889 in a small Austrian town, he quit school at the age of sixteen, moved to Vienna at eighteen, and at twenty-four ended up in Munich, where he soon enlisted as a soldier in the First World War. Entering politics in 1919, Hitler took over the tiny German Workers’ Party — renamed the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazi Party) — and became a main attraction on Munich’s boiling right-wing political circuit. In 1923, he mounted a coup d’état that failed spectacularly. Following a year in prison, he refounded his party, beginning the long march to power. Eight years of zigzag struggle and strife followed, with near-death experiences and surprise triumphs. Hitler climbed to within grasping distance of the German chancellorship in 1932. But his star began fading. He seemed in decline, dropping four percentage points in a national election, when an improbable series of events in January of 1933 saved him — and made him Germany’s chancellor.

Wilhelm Hoegner. A Social Democratic Bavarian politician, Hoegner tried in vain to warn Germans of Hitler’s vicious intentions.

Heinrich Hoffmann. Hoffmann, a jolly and bibulous Munich photographer, developed a unique relationship with Hitler. Gaining exclusive access to the rising politician, he covered all Hitler’s dramatic election campaigns as well as his informal moments away from politics.

Alfred Hugenberg. Born in 1865, the thick-girthed, mustachioed Hugenberg was a fervent nationalist, business baron, and newspaper mogul turned politician. Temperamentally at odds with Hitler, even when they agreed on policy, Hugenberg became the linchpin in Hitler’s hopes for the chancellorship. At the last minute in 1933, Hugenberg reluctantly agreed to serve in Hitler’s cabinet, enabling the Nazi leader’s ascension to power.

Karl Kaufmann. Kaufmann was a Nazi activist in northwest Germany who became Hamburg gauleiter.

Harry Kessler. A member of the German nobility and a former soldier, diplomat, and patron of the arts, Count Kessler was a well-met man-about-Germany, especially in Berlin. His voluminous diary entries written during the Weimar Republic offer acerbic insights into the political and social life of the period.

Karl Liebknecht. A leader of the Spartacist League, which became the German Communist Party, Liebknecht tried in vain to declare Germany a soviet republic in November of 1918. He was murdered during the violent upheavals in January of 1919.

Erich Ludendorff. A hero of the First World War, Ludendorff promoted the legend that German armed forces had been stabbed in the back by home-front shirkers. The retired general allied himself with Hitler in his failed 1923 putsch attempt. In 1925, Ludendorff ran for president and lost badly.

Rosa Luxemburg. A coleader of the Communists and a far-left theorist, Luxemburg was assassinated in January of 1919 by right-wing Free Corps units that were defending the government of Friedrich Ebert.

Melita Maschmann. Maschmann was a Berlin teenager drawn to Hitler’s promise of a classless “national community” and a return to German greatness.

Karl Mayr. Hitler’s commanding officer after the First World War, Captain Mayr sent the Nazi leader to a one-week training course in political history — a turning point in Hitler’s life. Assigned by Mayr to teach nationalistic doctrine to new recruits, Hitler discovered his talent as an orator.

Hermann Müller. Germany’s last Social Democratic chancellor during the Weimar Republic, Müller and his five-party coalition collapsed in March of 1930, ushering in an era of “presidential cabinets” that ruled more by decree than parliamentary legitimacy. This was the beginning of the end of German democracy.

Carl von Ossietzky. Editor of the renowned left-liberal weekly Die Weltbühne (The World Stage), Ossietzky ridiculed Hitler as a rube with no future. His dismissive essays were emblematic of elite thinking during Hitler’s rise.

Franz von Papen. A Catholic aristocrat from Westphalia, Papen was a lightweight politician tapped by Kurt von Schleicher as Germany’s chancellor in 1932. When Schleicher eased Papen out five months later, the nobleman sought revenge by making common cause with Hitler. Papen’s maneuverings — and special influence with President Hindenburg — made Hitler chancellor in January of 1933.

Franz Pfeffer von Salomon. A First World War veteran and Free Corps fighter with a penchant for brutality and discipline, Pfeffer was commander of the Storm Troopers from 1926 to 1930.

Walther Rathenau. A leading businessman who served as Germany’s foreign minister, Rathenau in 1922 initiated the Treaty of Rapallo, declaring a final peace between Germany and Russia. A moderate liberal and a Jew, Rathenau was assassinated by a right-wing hit squad.

Angela Raubal. Hitler’s half sister, Angela was the mother of Geli Raubal, arguably the love of Hitler’s life. Angela sometimes traveled with her daughter on Hitler’s trips and became his housekeeper when he acquired a mountain house in the German Alps above Berchtesgaden.

Geli Raubal. Born in 1908, Geli moved into Hitler’s spacious Munich apartment in 1929. She and “Uncle Alf” — he was nineteen years her senior — became a couple around town, leading to speculation about the real nature of their relationship. In 1931, at age twenty-three, Geli was found dead in her room under suspicious circumstances that could have derailed Hitler’s career.

Fritz Reinhardt. A Bavarian Nazi gauleiter who developed a correspondence course for Nazi Party public speakers, Reinhardt (no kin to Max) had turned out several thousand trained orators by the time of the crucial 1930 election.

Max Reinhardt. Austrian-born Reinhardt was the most celebrated German-language theater director of the 1920s, overseeing eleven different stages in Berlin alone. As a Jew, he was vilified by the Nazis.

Ernst Röhm. A scar-faced First World War captain, Röhm took part in the 1923 putsch attempt but later split with Hitler. After several years in exile in Bolivia, Röhm returned to the Nazi fold, taking command of the Storm Troopers and assisting Hitler during his final negotiations for power. Hitler had him murdered in 1934.

Alfred Rosenberg. An ethnic German from Estonia, Rosenberg became a Nazi Party ideologue and editor of the Völkischer Beobachter. Rosenberg’s massive tract The Myth of the Twentieth Century was overshadowed by Hitler’s own book Mein Kampf.

Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht. The son of pro-American parents, Schacht became a leading banker and nationalist politician who supported Hitler. He lent economic gravitas to the Nazi movement as it was rising to national prominence after the 1930 elections, influencing other businessmen to support Hitler.

Philipp Scheidemann. A Social Democratic politician, Scheidemann earned his place in history by single-handedly proclaiming, on November 9, 1918, the end of monarchy and the beginning of republican democracy in Germany.

Kurt von Schleicher. An armchair general who rose high in the military through his political connections, Schleicher became part of the influential camarilla around President Hindenburg. Though appointed chancellor in late 1932, Schleicher lasted only fifty-seven days in the job. Hitler had him murdered in 1934.

Walter Stennes. A Storm Trooper commander, Stennes twice rebelled, denouncing Hitler as an “un-Germanic” despot and stirring fears of a general uprising. Hitler had him purged.

Gregor Strasser. An artillery officer during the First World War, Strasser was trained as a pharmacist but soon entered Hitler’s orbit. The big Bavarian with the hearty laugh became the Nazi Party’s most energetic organizer and recruiter, building a grassroots network that drove the Nazis’ nationwide electoral successes. With administrative skills and a common touch, Strasser became the second-most-powerful man in the party. Yet he never quite accepted Hitler’s self-deification, and at the eleventh hour of their long struggle together, he deserted Hitler.

Otto Strasser. The younger and brainier brother of Gregor Strasser, Otto was a left-leaning Nazi whose Marxist writings in the newspaper he owned with Gregor led to a break with Hitler.

Gustav Stresemann. The son of a beer distributor, Stresemann rose to become Germany’s foreign minister during the Weimar Republic. The only politician to serve in eight successive cabinets, Stresemann succumbed to a stroke at the age of fifty-one, in 1929, depriving Germany of one of its most skilled moderate politicians.

Cosima Wagner. Cosima was Richard Wagner’s widow and the matriarch of the Wagner clan in Bayreuth.

Richard Wagner. Born in 1813, Wagner became the reigning genius of German musical composition and was renowned for his complex themes and dramatic orchestration. Best known for operas based on Norse mythology, he had a profound influence on German nationalist politics. To Hitler, Wagner was a hero on par with Frederick the Great and Martin Luther.

Winifred Wagner. Married to Richard Wagner’s son, Siegfried, Winifred was born in England but raised in Berlin. She became an early supporter of Hitler, sending him gifts in prison and inviting him to the family mansion in Bayreuth.

Bernhard Weiss. The Jewish deputy police chief of Berlin, Weiss was the butt of vicious anti-Semitic satirizing in Goebbels’s newspaper. Goebbels peremptorily gave Weiss the nickname Isidor — and it stuck in the popular imagination.

Wilhelm II. The last of the Hohenzollern kings of Germany and Prussia, Kaiser Wilhelm assumed power in 1888. The erratic monarch fired Otto von Bismarck and began a turbulent reign that in 1914 helped plunge Germany into the First World War. When Germany capitulated, in 1918, Wilhelm fled Berlin for the Netherlands and within days abdicated the throne.

August Wilhelm of Prussia (Auwi). One of six sons of Wilhelm II, Prince Auwi was an early supporter of the Nazis. Auwi surrounded himself with artists and scholars and was rumored among the Nazis to be gay. Though they sometimes ridiculed him, the Nazis welcomed the whiff of royal approval that Auwi lent to their movement.

Owen D. Young. Founder of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), Young in 1929 led a second reparations commission to further reduce and extend Germany’s post–First World War reparations payments. It was called the Young Plan.

A NOTE ABOUT STORM TROOPERS

The term Storm Troopers refers to the Sturmabteilung, or “storm detachment,” of the Nazi Party. Often abbreviated SA, the Storm Troopers began as a security detachment to maintain order at Nazi rallies. The brown-shirted paramilitary group later morphed into the party’s street-fighting force and grew to more than a million members — as many as in the rest of the civilian Nazi Party. Though forbidden to bear firearms, violence-minded Storm Troopers often carried blackjacks, brass knuckles, and other concealable weapons and became a key element in Hitler’s rise to power. The Sturmabteilung (SA) is referred to throughout this book as the Storm Troopers.

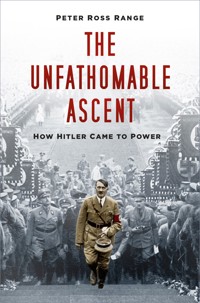

A NOTE ABOUT PHOTOGRAPHS

The photograph of Adolf Hitler on the following page, and on the pages separating this book’s five parts, are the work of Hitler’s photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann. Hoffmann began photographing Hitler in Munich in the early 1920s. He often used glass-plate negatives for posed studio pictures. After the Second World War, Hoffmann’s sometimes cracked or broken glass plates ended up in the U.S. National Archives Collection of Foreign Records Seized. In recent years, Archives preservationist Richard E. Schneider painstakingly reassembled many of the damaged plates and digitized 1,270 of them. The six images in this book stem from that work.

A NOTE ABOUT MAPS

The map of Germany during the Weimar Republic on pages 2–3 is by David Lambert. The map of the Berlin Government District in January 1933 on page 339 is by Shannon K’doah Range.

Prologue

It was a stunning turn of events. On a bitterly cold Monday night, Berlin blazed with torchlights and thundered with the cadence of martial drums. It was January 30, 1933, and Nazi Storm Troopers by the tens of thousands, and civilians in nearly equal numbers, were marching through the historic Brandenburg Gate. An excited German radio announcer described the march as “a human river” and “a historic moment whose full meaning is not yet clear to us.” To an American journalist, the scene was the “greatest torchlight procession in German history.”1 Turning up Wilhelmstrasse, the German capital’s main corridor of power, the marchers belted out their national anthem (“Germany, Germany, above all!”), raising their right arms and cheering as they passed the chancellery. In an open second-story window, a man in a dark suit extended his right arm in return. It was Adolf Hitler’s moment of triumph.

Seven hours earlier, President Paul von Hindenburg had sworn in forty-three-year-old Hitler as chancellor of Germany. The installation of a former First World War foot soldier into Germany’s highest government office came as a shock even to those in the capital who closely watched the baffling political churn of a country in free fall. Of all the speculations swirling through Berlin during the past month of uncertainty, the least likely was the emergence of a government led by the radical Nazi Party chief. Secretive behind-the-scenes negotiations had left Germany’s leading newspapers and prognosticators grasping at straws —and guessing wrong. Yet Hitler’s ascent momentarily solved the urgent conundrum of who was to run a nation that had become effectively leaderless. The appointment of a Nazi-led cabinet was a desperate stab at finding a way out of an economic depression that had left six million Germans unemployed and the country on the brink of civil unrest.

Still, the portentous choice of Hitler, the leader of an authoritarian movement bent on dictatorship and conquest, augured a political shift so profound that few could imagine the totalitarian calamities that lay ahead. In the coming twelve years, Hitler would launch the most destructive war in history, murder eight million Jews and other allegedly inferior people, subjugate most of Europe, and come close to adding both Russia and Great Britain to that stunned and abject list. When his perverse crusade ended in the hellfire of 1945, much of Germany would lie in ashes and ruins. Hitler’s ten-minute swearing-in ceremony, on a cloudy winter day in 1933, would have greater impact on the planet than any other single administrative act in history.

Those horrific events still lay in the future. As Hitler’s jubilant supporters tromped past on this night in Berlin, the Nazi leader’s beaming presence in the spotlit window was the improbable culmination of a circuitous, often quixotic, and very nearly unsuccessful march to power. After thirteen years in public life; after eight years of electoral politics; after frequent setbacks and restarts; after detours, disappointments, and party purges; after nonstop electioneering and Nazi Party activism; after the sensational defection of his top lieutenant only weeks before; after being dismissed, ridiculed, and frequently left for politically dead — and after surprise successes that brought fully one-third of German voters into his camp — Hitler had reached his goal. The Nazis, finally, were at the pinnacle of power.

Watching over Hitler’s shoulder as the torches and drums streamed down Wilhelmstrasse, propaganda meister Joseph Goebbels felt it was “like a fairy tale.”2

Hitler’s ascension indeed seemed like a magical salvation to many in a country buffeted since 1918 by wartime defeat, national revolution, fractured politics, and grinding economic crisis. To Hitler’s supporters, a rebirth seemed at hand. To others, it was a moment of shock. Even during Hitler’s quasicoronation, on this frenetic night in Berlin, many in the educated upper middle class already feared the implications of Nazi rule. Among those watching the torchlight parade were the parents of fifteen-year-old Melita Maschmann, a Berlin schoolgirl standing with her family on the fringe of the procession. Melita knew that her father and mother, though staunch nationalists, disapproved of Hitler’s paramilitary Storm Troopers and their rough tactics; they rejected the Nazis. Yet Melita, who listened to her parents read the newspapers aloud every day, thrilled to Hitler’s promise of a new “national community” of all Germans, regardless of class or background. The teenager had picked up her reformist ideas from her mother’s seamstress, a limping, hunchbacked woman who saw hope in Hitler’s message. As Melita stood on the sidewalk watching the bright-faced torchbearers — many of them teenagers, like her — she envied the Nazis in the parade. She saw in their optimism a future she wanted to be part of. Without telling her parents, Melita secretly “longed to hurl myself into this current, to be submerged and borne along by it.” The young Berliner would soon join millions of other idealistic teenagers in the Hitler Youth and League of German Girls organizations. After that, she became a committed cog in the Nazi machine.3

Today the question still looms: how did an unknown failed painter from Austria weave his way through the dense thickets of post–First World War politics to become the last man standing when Germany’s democracy crumbled?

A nobody from nowhere, Hitler had none of the makings of a public figure. He was not a working-class activist who rose through the ranks of Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) — as did Friedrich Ebert, the Weimar Republic’s first president.1 The Nazi leader was no schooled intellectual — as were Marxists Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, leaders of the Spartacist League, which morphed into Germany’s Communist Party (both were murdered during violent upheavals in 1919). Hitler had nothing in common with university-trained businessmen such as Walther Rathenau and Gustav Stresemann, who became the Weimar Republic’s revered foreign ministers. The unsophisticated Austrian was hardly a captain of industry — as was Alfred Hugenberg, who shouldered his way into politics by building a newspaper empire. Hitler didn’t spring from the elite officer corps, as did General Erich Ludendorff and Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, who rose to the top of the military before entering politics — Ludendorff as a right-wing reactionary and Hindenburg as Germany’s second president. The highest military rank Hitler attained during his four and a half years in uniform in the First World War was private first class.2

For decades we have struggled to understand the rise to power of Hitler, the accidental politician. Yet the facts, the events, and the politics of his climb are available for examination and telling. They reveal Hitler’s nearly unbelievable journey from beer-hall rabble-rouser to national leader between 1925 and 1933. His serpentine path during the eight years that really mattered shows that, despite his obsessive self-belief, his ascension to power was far from foreordained. His climb was, politically and historically, a concatenation of bluster, accidents, and a train wreck of epic proportions laced with flashes of political skill. These latter included dogged organizing, a brilliant political ground game, and an exceptional rhetorical gift.4 Hitler’s lawyer and confidant, Hans Frank, later governor-general of occupied Poland, called the Nazi leader’s rise an “unfathomable ascent.”5

Hitler’s journey is a political cliff-hanger of unexpected twists, turns, and near-death experiences from which the protagonist always recovered through political savvy, astonishing tenacity, raw brutality, and, often enough, pure luck. Hitler was saved by his fanatical self-assurance (his “will”), his native oratorical talent, his instinctive propagandistic skills, an uncanny feel for the mood of the masses, and the choice of a gifted number two man with keen administrative skills. The Nazi leader profited from a nearly perfect storm of constitutional weaknesses in Germany’s virgin democracy, the profound splintering of the German body politic, the untimely deaths of statesmen who might have thwarted his climb, the onset of the Great Depression, continual underestimation by the political establishment, the woeful incompetence of contemporaneous players on Germany’s political stage, and the craven motives of others at a critical moment.

Despite all that, Hitler had frequent close brushes with political obscurity. But for an unlikely sequence of events in January of 1933, Hitler would quite possibly have remained only a footnote to history. During the last four weeks of his political odyssey, Hitler outmaneuvered his political competitors with tactics that were alternately Machiavellian and melodramatic. Throughout that period, his moves were opaque and confusing even to his closest confidants. Like the protagonist in a bedroom farce, Hitler was constantly opening and slamming doors, appearing and disappearing without warning, engaging and rejecting, making outrageous demands, then suddenly leaving the stage. The play unfolded in late-night meetings at posh secret venues and did not reach its denouement until the very day Hitler was sworn in as chancellor. His chancellorship was in doubt up until the last fifteen minutes before he took the oath.

But that gets ahead of the mind-boggling story.

___________

1 The German president was in theory the head of state — the holder of a ceremonial post like the British monarch’s but invested with key powers that would, in time, prove fateful. The German chancellor was the head of government, analogous to the British prime minister.

2 Hitler’s rank was Gefreiter, which has been erroneously translated for decades as “corporal.” Unlike an American corporal, a Gefreiter was not a noncommissioned officer; a Gefreiter had no command over anyone. He was merely a buck private promoted to private first class.

Part One

REBIRTH AND REBUILDING

(1925–1928)

Scarcely a week passed, but a huge procession of starving excitable men would march through the streets. There was a constant tension in the air. One government followed another. The Marxists held huge mass meetings. The population was split up into tiny parties. The atmosphere was teeming with all sorts of plans. There was no unity of purpose anywhere.

— A government clerk who joined the Nazi Party, 19261

This horrible sense of insecurity kills people. You get trained in a skill, and afterward you are out on the street. . . . You have a horrible feeling of uselessness.

— Paul R., a twenty-year-old cabinetmaker2

1

BACKSTORY

Herr Hitler is, if I may say so, a born popular speaker.

— German army recruit, 1919

It was the unlikeliest moment in the unlikeliest of venues. On a winter night in 1925, a convicted traitor was mounting a political comeback in the same beer hall where he had committed treason only sixteen months before. Surrounded by delirious supporters, welcomed by a Bavarian band blasting his favorite marching tunes, and protected by a massive turnout of Munich’s finest — one of Germany’s largest police forces — Adolf Hitler, at thirty-five, was serving notice that he was back.

The fiery-eyed Nazi leader had been written off in 1923 when he attempted a coup d’état that failed. Now, improbably, he was staging his own rebirth. It was just the kind of bold stroke that had appealed to the dreamy Austrian throughout his checkered and ill-directed life.

Adolf Hitler was born in 1889 in the tiny Austrian burg of Braunau am Inn. He was the fourth child of the third wife of a local customs official, Alois Hitler, who drank heavily and often beat his sons and his wife. While taking his morning wine one day at the local pub, Alois keeled over, dead at the age of sixty-five; Adolf was only thirteen. Released from his father’s dominance, the restless teenager quit school three years later, at sixteen, and declared himself an artist who also had an interest in architecture. For two years, he drew and painted everything in sight, and redesigned (in his head) every major building in Linz, the town where his father had relocated the family when Hitler was nine years old. Then, at eighteen, young Hitler migrated to the bright lights of Vienna, Austria’s capital. There the headstrong youth met his comeuppance: he was summarily rejected for admission to the renowned Academy of Fine Arts. “Test drawing unsatisfactory — few heads,” noted the examiners.1 Without a high school diploma, he dared not follow the examiners’ suggestion that he might apply to architecture school instead.

Devastated, Hitler was soon homeless. After several months of uncertain living arrangements, including at least a few nights on park benches, the vagrant young man fetched up in a men’s shelter, where he earned a meager living by drawing postcard-style paintings of Viennese landmarks for the tourist trade. In his spare time, he became a voracious reader of history, architecture, and politics, often picking up free pamphlets in all-night cafés or spending long hours in a small bookstore. He began lecturing his hapless housemates on the evils of international political movements such as socialism.

By the age of twenty-four, Hitler was on the lam from his draft board. He was due for service in the army of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, an enlistment that could last for years. Hopping a train to Germany, he stepped down in the first big city he came to: Munich. The capital of Germany’s southernmost state, Bavaria, Munich gleamed with monuments, museums, and stately architecture; Hitler fell in love. Yet he was penurious, aimless, and stuck in a rut, still peddling watercolors and sketches of city sights. After little more than a year, however, the draft dodger was rescued by the unlikeliest of events: war.

The First World War broke out in the summer of 1914. Like many Austrians and Germans, Hitler was caught up in war fever. Bitterly rejecting the multicultural Austro-Hungarian Empire of his birth as a misbegotten political construct, he eagerly embraced a sense of German ethnicity. He joined excited mobs on a Munich square, loudly welcoming the coming war. He eagerly enlisted in a Bavarian regiment that did not reject him because of his Austrian origins. He shared what Ernst Simon, a German Jew, referred to as the “intoxicating joy” of going to fight for his homeland.2 The young Hitler, who had constantly played war games on the meadows near his boyhood home, was soon on his way to fight the real thing on the fields of Flanders and in northern France. Soldiering was Hitler’s first actual job. War became the primal transformative experience of his life, giving shape, purpose, and discipline to a chaotic existence.

Hitler began to grow up. The foot soldier showed skill in improvisation and self-preservation. Following several harrowing months on the front lines, he cadged a relatively safe and cushy job as staff courier at regimental headquarters far behind the trenches. While his messenger’s job gave him a “warm, lice-free stretcher” to sleep on, his forays to the front put him often, though briefly, in mortal danger. He was wounded twice. Promoted from buck private to private first class, Hitler was awarded an Iron Cross Second Class and an Iron Cross First Class. The value of his medals is uncertain: sixty other men from his regiment received the First Class award on the same day.

Hit by a gas attack in 1918, Hitler lay recovering in a hospital north of Berlin when news arrived that Germany had surrendered to the Allied powers. After five years of slaughter, with almost two million German soldiers killed, the fatherland was defeated. Adding to the tragedy — at least in Hitler’s eyes — was the fact that the long-reigning monarchy of Wilhelm II had been deposed. A Social Democratic–led revolution had turned Germany into a democratic republic.

Germans were shocked by their generals’ capitulation, a prospect about which they had not been warned. Like many Germans, Hitler was stunned and angered by the news of the country’s defeat. He later claimed that Germany’s loss and its conversion into a democracy had persuaded him on that very day to enter politics. Yet he showed no immediate signs of seeking a profession in public life. Half a year after hostilities ended, the rifle-toting soldier was still in the army while six million other German servicemen demobilized. With no training, no skills, and no prospects, the uneducated Hitler’s only hope for a roof, a cot, and three meals a day was the military.

Luck was on Hitler’s side. After he returned to Munich, the thirty-year-old was eventually attached to a new training and propaganda unit. Its job was to combat the rampant Marxist ideas circulating among recruits in the new, slimmed-down army — the Reichswehr. The unit’s commander, Captain Karl Mayr, regarded Hitler as a “tired stray dog looking for a master.”3 But Mayr needed lecturers for his propaganda program, so he sent Hitler to a one-week course in political history at the University of Munich. This serendipitous assignment unlocked Hitler’s talents as a declaimer and debater. His fierce argumentative skills surfaced in after-class discussions in the hallways, which were noted by his professor. Captain Mayr dispatched Hitler to harangue new troops about German nationalism and the perfidy of Marxists (including Communists and Social Democrats) at a military camp outside Munich. Strident and full of examples drawn from his own casual but wide reading of history, Hitler enthralled his young students with patriotic and unabashedly anti-Semitic arguments. “Herr Hitler is, if I may say so, a born popular speaker,” wrote one soldier in a postcourse evaluation.”4

Hitler was again transformed. Through a week of talking, he had discovered his singular gift. “I could ‘speak,’” he noted with astonishment.5 The unpromoted private with the big mouth and bigger ego had stumbled into his life’s work.

In another fortuitous turn, a month later, Hitler’s path into politics opened. Curious about the burgeoning right-wing political scene, which was dominated by rejection of the parliamentary republic, he attended a meeting of the fledgling German Workers’ Party. He claimed that, at a gathering of several dozen attendees in a dim Munich pub, he stood up and demolished the argument of a speaker who favored Bavarian separation from Germany. Hitler, on the other hand, fiercely embraced pan-German unification, including Austria. The other man was haplessly driven from the room “like a wet poodle,” insisted Hitler — a possibly invented or embellished story.6 Whether the account is true or not, there is no question that Hitler was drawn to the little political group. A watershed was reached when Hitler decided to join the party. It was autumn of 1919.

The freshly minted new member of the German Workers’ Party wasted no time in asserting his rhetorical skill and authoritarian muscle. Though a neophyte, Hitler became the party’s chief stump speaker within five months. His maiden outing, in the capacious Hofbräuhaus, in February of 1920, turned into an uproarious melee. With his fiery orations, he was the attraction who could draw listeners and money to the party (in those days, people paid to hear a speech). As its rising star, Hitler gained control and elbowed aside the group’s cofounders. He added two words to the party’s name, restyling it the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. It was quickly nicknamed the Nazi Party (Nazi derives from Nationalsozialistisch, the German word for “national socialist”).

On a Munich political stage filled with right-wing groups vying for attention, Hitler’s high-flown rants attracted notice. Quickly regarded as the most dynamic speaker on the local beer-hall circuit, he became an act that people wanted to see. His rabid confidence, edgy ideas about race, politics, and foreign conquest, and theatrical speaking style often left him drenched in sweat. Women, in particular, were fascinated by the unmarried ex-soldier with the apocalyptic pronouncements (“Marxism . . . will overrun the rotten edifice of our national life”)7 and undiluted sense of messianic mission (“A new German Reich will rise again!”).8 Hitler rejected accommodation of the humiliations and burdens imposed by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles — including its “sole war guilt” clause and heavy reparations requirements. To listeners who despaired over Germany’s economic and political plight, his message was both sizzling and inspirational. His was a combative voice for frustrated and angry people.

Speaking in beer halls and even in private drawing rooms, the sharp-voiced Nazi leader turned his party into a fast-growing upstart “movement,” as he liked to call it. By early 1923, the Nazi Party could count twenty thousand members. After a busy spring and summer, membership nearly tripled, to fifty-five thousand.1 The Nazi Party’s appeal was soaring in a time of turmoil.

Postwar conditions had led to food shortages and hunger riots. German police were firing on starving Germans. “As I came home,” remembered one former frontline soldier, “I saw hungry, dispirited faces, a people to whom nothing mattered any longer. The most anybody could wish for was a square meal and being left in peace.”9 Hyperinflation meant that there were four trillion marks to the US dollar. People were desperate. “Rice, 80,000 marks a pound yesterday, costs 160,000 marks today,” reported one newspaper. “The day after, the man behind the counter will shrug his shoulders, ‘No more rice.’ Well then, noodles! ‘No more noodles.’ . . . Somewhere patience explodes. . . . then comes the umbrella handle . . . crashing through the glass cover on the cream cheese. And the cop standing watch outside pulls a sobbing woman from the store.”10

Germans bitterly watched French and Belgian troops march into the industrial Ruhr region four years after the end of the First World War in retaliation for Germany’s unpaid war reparations. By autumn of 1923, Germany seemed headed toward civil war. Bavaria was in a state of near rebellion against the national army. Hitler sensed a chance to steal a march on history. He made the most foolish decision of his political life.

The Nazi leader’s near-fatal mistake occurred on November 8, 1923, when he staged a coup d’état. For four years Hitler had agitated for an authoritarian government to replace Germany’s unwieldy parliamentary republic — and for the “criminal” leaders of the 1918 revolution to “hang from lampposts.” Now he decided impulsively to move against the government of Bavaria and the national government in Berlin. While people on other parts of the German political spectrum advocated a form of authoritarian government, none was as passionate or impetuous about it as Hitler and his Nazis were. With three thousand armed men at his disposal — and the windfall of finding Bavaria’s key leaders gathered under a single roof on a single night — Hitler staged a putsch in Munich’s packed Bürgerbräukeller beer hall. Bursting through the doors with a platoon of insurrectionists in helmets and battle gear, Hitler bounded onto a chair and fired his Browning pistol into the drinking establishment’s coffered and chandeliered ceiling. “The national revolution has begun!” he shouted in his best caudillo style, stunning an audience of several thousand and stupefying Bavaria’s ruling triumvirate — the state commissioner, state police chief, and divisional army commander.

The entire beer hall was now Hitler’s hostage. With his combat units seizing other key points around Munich, he appeared to have succeeded in deposing the leadership of one of Germany’s most important states, Bavaria. In the coming days the wild-eyed revolutionary planned to march on Berlin, where he would unseat the hated Weimar Republic along with its Social Democratic president, Friedrich Ebert.

But Hitler’s hasty putsch was poorly organized and soon crumbled. Within seventeen hours, a hail of gunfire by government troops brought down his march through the center of Munich, intended to stir up support for his revolution. Fifteen of Hitler’s followers were killed, along with one bystander and four government riflemen. The Nazi firebrand escaped death only by inches; the man marching arm in arm with him in the parade’s front row was struck by a fatal police bullet. Other shots hit Ulrich Graf, Hitler’s bulky bodyguard, as he fell atop Hitler in the melee. Fleeing the scene, the lightly injured Nazi leader (he suffered only a dislocated shoulder) hid for two days in a friend’s villa south of Munich. When police surrounded his hideout, Hitler pulled out his pistol and threatened to take his own life (he had already mentioned suicide twice as his coup attempt crumbled).11 But his host, Helene Hanfstaengl, yanked the firearm out of his hand and tossed it into a nearby flour barrel. Hitler was captured and thrown into the slammer.

At age thirty-four, Hitler seemed finished. “The Munich putsch definitely eliminates Hitler and his National Socialist followers,” opined the New York Times.12

But his burning ambitions were not so easily quelled. Sentenced to a wrist-slap prison term of five years for high treason with the possibility of early parole, the Nazi leader spent just over a year behind bars. After a bout of depression — and another brief suicide attempt, via hunger strike — he underwent a revitalization and reorientation of his political plans. He restyled himself as a political savant and Germany’s redeemer. With a head full of grand plans and mythic notions of greatness, Hitler in his jail cell drafted a political memoir that bulged with megalomania and certitude. The self-assured Nazi put himself in the company of Prussian king Frederick the Great, Reformation leader Martin Luther, and opera composer Richard Wagner. Sprung from prison just before Christmas in 1924, Hitler could think of only one thing: starting over.

___________

1 Though large, fifty-five thousand was an insignificant number on the national scene, where the Social Democrats had more than one million members. Even the Communists boasted three hundred thousand members.

2

RESURRECTION

Either the enemy will walk over our dead bodies or we will walk over his!1

— Adolf Hitler, Bürgerbräukeller speech, 1925

Released from Landsberg Prison on December 20, 1924, a contrite Hitler played the reformed revolutionary. The newly liberated Nazi announced that he intended to forsake armed revolt in favor of the ballot box. “We must follow a new line of action,” he told a supporter. “Instead of working to achieve power by an armed coup, we shall have to hold our noses and enter the [parliament]. . . . If out-voting them takes longer than out-shooting them, at least the results will be guaranteed by their own constitution.”2

Hitler’s hope now lay in long-haul politics, not the quick fix of revolution. In a meeting with Bavarian governor Heinrich Held, the seemingly penitent Nazi promised that he would attempt no more putsches if the government would lift the ban on his party and his public speaking. He would seek power only by political campaigning, not by the gun.

“The wild beast is checked,” Held told his aides. “We can afford to loosen the chain.”3

With his political resurrection scheduled in the same Bürgerbräukeller where he had overreached in 1923, Hitler was now certain that he could go all the way, no matter how long it took. Among Munich’s large drinking venues, the Bürgerbräukeller — an upscale establishment on the slope of the Isar River, which bisected Munich — was special. Its atmosphere was more banquet hall than beer brawl: its guests were often pillars of the bourgeoisie, not just cloth-cap workers or mountaineers in lederhosen. By choosing the Bürgerbräukeller for his political revival, Hitler was sending a message: his aborted mini coup had not been wrong in purpose, just mistaken in method — and certainly premature in timing. This time he would do it right.

At quarter past eight on the evening of February 27, 1925, the Nazi leader’s Mercedes touring car — a gift from a rich supporter — pulled up in front of a seemingly besieged beer hall. Munich police had blocked off streets for several blocks and set up a triple security cordon. More than a thousand ticket-waving Hitler supporters clamored to get inside, but the doors had been slammed shut. Three thousand attendees had already overfilled a hall that seated only two thousand; the Nazis had oversold Hitler’s stagy “second coming.” One desperate Hitler fan shouted to a reporter passing through the police checkpoint: “One hundred marks to temporarily ‘borrow’ your press credentials!”

Inside, the journalist had to declare that he was “not a Jew” before being led to the press seats. A loud band stirred the agitated crowd with Bavarian tunes and military music, including Hitler’s favorite, “The Badenweiler March.” A gaggle of young women who had arrived at 9:00 a.m. in the Bierstüberl (a side room) cadged good seats when the main hall opened at 4:30 p.m. Hall monitors wearing Nazi armbands handed out little swastika flags. Finally, on a cue from a Nazi floor manager, the band ended its blaring with a great cymbal crash, the hall filled with roars, and people climbed onto their chairs to cheer the man they had waited for months to see again. Through a double phalanx of Storm Troopers with raised arms strode the unprepossessing politician with the smudge mustache, staring sternly ahead.4

“He passed by me quite close, and I saw a different person from the one I had met now and then in private homes,” recalled an observer of Hitler’s entrance ritual in another beer hall on another night. “His gaunt, pale features contorted as if by inward rage, cold flames darting from his protruding eyes, which seemed to be searching out foes to be conquered.” The observer wondered if Hitler was possessed of “fanatical, hysterical romanticism with a brutal core of willpower.”5

So it was on this night at the Bürgerbräukeller. The Nazi leader’s unerring sense of theatrics — the emotional appeal of uniforms, martial music, flags, colors, the stiff-armed Nazi salute, a delayed entrance — infused the political show. The boisterous crowd waved their Nazi banners and craned their necks toward the grim-faced man with the penetrating blue eyes. Their cheering and heiling went on for a full ten minutes. “Hitler still knows how to make hearts race a little faster,” noted one newspaper. “When Hitler shows up, people want to have been there.”6

After sixteen months away from the beer-hall circuit, Hitler had lost none of his demagogic skills. During four years as a political speaker, he had taught himself a thespian’s repertoire of gestures, imprecations, and throaty barks. Waving his arms and wagging a reproachful finger toward invisible enemies, Hitler rolled his r’s in an exaggerated growl that gave an aggressive edge to his words (he never talked that way conversationally, said his secretary). In perorations that lasted up to three hours, he had learned to rivet his audiences with punitive rhetoric, populist sentiments, lurid anti-Semitism, mocking put-downs, and sly irony. His voice rumbling low before rising into whole-body invective, he mesmerized audiences with elaborate historical theorizing followed by sweeping utopian visions. He constantly repeated catchphrases such as “the November criminals” to denigrate the democratic leaders of the Weimar Republic as perpetrators of an illegitimate enterprise.

Tonight, the practiced firebrand evoked his favorite bugaboos, conspiracy theories, and nationalist fixations.7 Giving his eager followers the political red meat they had come to hear, Hitler stroked their emotional chords, thrumming anger at real or perceived insults to national pride. The Nazi speaker invoked the themes and tropes that would constantly recur in the 692 speeches he would make in the coming eight years. These included Germany’s loss of its “racial consciousness”; its broken sense of nationhood; its false belief in its own war guilt, as prescribed by the loathed Treaty of Versailles; the importance of “perpetual struggle” as the permanent condition of mankind, implying the inevitability of another war; the need to create a Volksgemeinschaft — a national community — that would unite all Germans, regardless of class, religious denomination, or profession. (Hitler claimed that his was the only movement untethered to any existing economic or class interests such as the industrialists, the landowners, the bourgeoisie, or the working class.)8 Only by elevating the state to primacy over the person, argued Hitler, could Germany reclaim its inherent greatness. Preaching with the fervor of a zealot, he promoted his radical gospel with the faux sophistication of a self-taught historical scholar.

In his political ramble, Hitler saved special venom for Jews. German Jews were a tiny minority — about 550,000 in a nation of sixty-three million, or less than 1 percent of the population. Yet since Jewish Germans were often prominent in science, business, banking, and publishing — as well as in critical areas of rural life, such as livestock trading — they were perceived by some as ubiquitous, all-powerful, and far more numerous than they were. In the German countryside, Jewish cattle merchants were sometimes demonized as oversexed predators whose religion allowed them to prey on Gentile women.9 Given the underlying anti-Semitism that had been latent throughout the fifteen-hundred-year presence of Jews in Germany, it was easy for Jews to be scapegoated as devious string pullers on the political left who had “stabbed Germany in the back” near the end of the First World War.10

Many Germans’ resentment of “the other” was triggered by the arrival since the 1880s of “Eastern Jews” driven from their homelands by pogroms in Russia and Poland. Sometimes wearing traditional Orthodox clothing or shtetl garb and working as Yiddish-speaking peddlers on the streets, the strange-looking new arrivals were demonized as drags on a depressed economy and as potential criminals — and even negatively stereotyped by long-settled, upper-middle-class German Jews who felt their assimilationist strivings were harmed by the Ostjuden (Eastern Jews). Walther Rathenau, an assimilated Jew, leading industrialist, and, briefly, Germany’s foreign minister, took the view that Eastern Jews were an “Asiatic horde” and an “exotic tribe.”11 To Theodor Wolff, a Jew who for twenty-seven years was the acclaimed editor of the highly respected Berliner Tageblatt newspaper, the self-segregating Easterners were “unpleasant haggler types.”12

Hitler seized on the virulent anti-Jewish sentiment that had burbled and stewed in Germany’s radical-right nationalist movements for the previous two decades — a revival of anti-Semitism that had begun in the mid-nineteenth century in France, Austria, and Germany. The First World War had only heightened latent anti-Semitism, leading to an official army census in 1916, intended to measure the number of Jews serving on the front lines. Designed to prove that Jews were underrepresented in combat and thus unpatriotic shirkers, the Judenzählung — Jewish count — in fact showed that Jews were overrepresented in combat relative to the percentage of them in the population. In all, more than eighty-five thousand German Jews served in the war, and 70 percent of them saw frontline duty. Thirty-five thousand were decorated for bravery, and at least ten thousand died.13 Those inconvenient facts, at first suppressed by the military but later publicized by Jewish groups, did little to dampen the growing anti-Semitism.

In Hitler’s telling, Jews had embarked on a plan of world domination through business success, sly cunning, and the promotion of communism. Flinging out unfounded generalizations, half-truths, and distortions, Hitler argued that Jews were an unlanded people with no country to call their own. They were parasites on their host nations with a pernicious internationalist rather than nationalist outlook. Punctuating the air with his raised finger, hurling his voice into the banquet hall, Hitler declared that Germany’s Jews were part of a “satanic power” whose goal was “to destroy the backbone of the nation-state, destroy the national economy, eliminate the racial foundations [of a country], and establish their own dictatorship.”

Combining his animus for Jews and Marxists into the term “Jewish Bolshevism,” the Nazi leader argued that Jews contaminated the blood of the German race. Jews were a “culture-destroying” people who weakened the German gene pool and would lead to the nation’s downfall. “Purity of blood” was Hitler’s first commandment. “The greatest danger for us is the foreign ‘racial poison’ in our bodies,” he declaimed. Turning graphic, Hitler declared that, in the fleshpot that was Berlin, one constantly saw “Jewish boy after Jewish boy with a German girl on his arm” strolling along Friedrichstrasse, the famous shopping mecca. This could only mean that “night after night, thousands and thousands of times, our blood is destroyed for eternity in a single instant. Children and grandchildren are lost to us forever. . . . Once poisoned, our blood can never be changed, and . . . it takes us further and further downward every year.”

The self-styled political serologist was dancing close to political pornography; evoking scenes of copulating couples was daring stuff in 1925. Yet the Bürgerbräukeller crowd loved it, giving Hitler’s words “loud agreement,” noted a stenographer.

Fanning his audience into a state of hatred for a perceived enemy — the most powerful of emotions — Hitler worked himself into a lather. Fighting the Jewish-Marxist “pestilence” could not be done “in a respectable style that inflicts no pain,” he foamed. Taking on the Communists had to be done with ruthless brutality: “Either the enemy will walk over our dead bodies or we will walk over his!”14

A gasp must have rippled through the plainclothes police spies and journalists in the audience as they scribbled “dead bodies” into their notebooks. Hitler had just crossed a line, possibly violating his promise to Governor Held not to seek power through violence. Making matters worse, Hitler insisted that his revived Nazi Party needed committed “fighters,” not educated parliamentarians.15 He would rather have a small party of passionate warriors than a large one made up of men not really “ready to die” for the cause. The true fighters, he claimed, could be found only “in the broad masses” — the sole source of men prepared to “use any means” to reach their goals.

Any means? Hitler had crossed another line.

Finally, Hitler got down to the real business of the evening: refounding the Nazi Party. His challenge was to reunify the warring splinters of the National Socialist and völkisch movements behind his sole leadership.1 For two months since leaving prison, Hitler had reached out to the squabbling rivals. While some felt it was time to drop their independent strivings, others resisted Hitler’s appeal to join him in a show of unity in Munich. Alfred Rosenberg, a little-loved Nazi Party intellectual, rejected the idea of artificial “brother kissing” at Hitler’s opening-night comeback rally. Ernst Röhm, the scar-faced former army captain who tried to start his own new militia while Hitler sat behind bars, also stayed away. Gregor Strasser, a bluff Bavarian who would soon rise to the number two spot in the party, also demurred.

Yet with six other Nazi leaders from two opposing factions on the podium with him, Hitler was able to stage a scene that was, as Rosenberg had predicted, a teary-eyed show of fraternal fealty. The tableau of seven men on the stage was a replica of the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, when Hitler had temporarily persuaded men from conflicting camps to join in his ill-starred coup. Tonight, Hitler was trying to take up where that act had left off. “The fighting is over,” Hitler said, because “today all of Germany is watching us.”

As it did in 1923, the spectacle ended with nearly all four thousand people in the Bürgerbräukeller singing the Weimar Republic’s national anthem, “Song of Germany”: “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles. . . .”2