Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

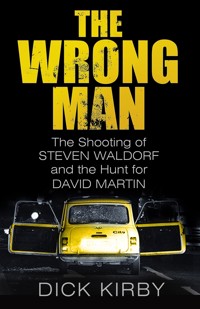

David Ralph Martin was a cross-dressing criminal who carried out a string of sophisticated offences in the 1970s and '80s. A prolific burglar, car thief, fraudster and gunman, he possessed a deep loathing of anyone in authority. In addition, he was a master of disguise and a veritable Houdini when it came to escaping from prison. After shooting a policeman during a botched burglary, he escaped from court on Christmas Eve, 1982. When police believed him to be in a yellow Mini in the Earls Court area with his girlfriend, they opened fire, only to discover they had shot an entirely innocent man – a 26-year-old film editor named Steven Waldorf. The investigation became a cause célèbre at the time, and was subsequently taken over by Scotland Yard's Flying Squad, of which the author was a member. One of the biggest manhunts in the history of the Metropolitan Police ensued, before Martin was finally arrested after dramatically fleeing down the tracks between two Underground stations. Author Dick Kirby reveals for the first time the inside story of the hunt for 'the most dangerous man in London', whose eventual arrest brought to an end one of the most contentious investigations in Met history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 382

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to Len and Beryl Monica Waldorf,who displayed great courage, dignity and compassionthroughout this case.

And also to Ann, who, like the Waldorf family, waited,wondered and worried.

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank first my long-time chum, the intrepid reporter Jeff Edwards for such a splendid foreword. Next Mark Beynon, the commissioning editor at The History Press, for his enthusiasm regarding this book. In addition, Paul Bickley of the Crime Museum, New Scotland Yard; Shannon Stroud, Freedom of Information Advisor, New Scotland Yard; Bob Fenton QGM, Honorary Secretary to the Ex-CID Officers’ Association; and Susi Rogol, Editor of the London Police Pensioner magazine, all assisted and I am most grateful to them.

Once more, I have to thank my daughter Suzanne Cowper and her husband Steve, together with my daughter Barbara’s husband, Rich Jerreat, who successfully guided me through the baffling minefield of computer land.

The following includes those who went to a great deal of trouble for me, some of whom delved into memories which must have been very traumatic, who gave most generously of their time and I am indebted to them. They appear in alphabetical order: Dave Allen, Frederick Arnold, Terry Babbidge QPM, Brian Baister QPM, MA, Roger Baldry, John Barnie, Jim Barrow, the late Nicky Benwell QPM, Alan Berriman, Colin Black, Alan Branch, Linda Brown, Colonel Markham Bryant MBE, DL, Nick Carr, Roger Clements, ‘Steve Collins’, Michael Conner, Bob Cook, Suzanne Cowper, Clive Cox, Paul Cox, Leo Daniels QPM, Robert Darby, John Devine, Neil Dickens QPM, Ken Dungate, James Finch, Peter Finch, Steve Fletcher, Jim Francis, the late Tony Freeman, Gerry Gallagher, Mick Geraghty, Martin Gosling MBE, Len Gunn, Gordon Harrison, Colin Hockaday, Steve Holloway, John Jardine, Barbara Jerreat, Len Jessup, Mark Kirby, Gus MacKenzie CFE, ACFS, Bill Miller, Alan Moss, Morgan O’Grady, Martin Power, Lester Purdy, Tom Renshaw, Eddie Roach, Michael Bradley Taylor QPM, John Twomey and Tony Yeoman. My thanks for the use of the photographs goes to Linda Brown, Nick Carr, Peter Finch, Gerry Gallagher, Damian Hinojosa, John Jardine, Len Jessup, Alan Moss, the Metropolitan Police, Lester Purdy, Tom Renshaw, Martin and Maria Steward and the author’s collection. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and the publishers and I apologise for any inadvertent omissions.

There were others who for a number of reasons either wished to remain anonymous or who were in a position to provide pertinent information and who chose not to do so. Bereft of their assistance, I have endeavoured to ensure that the content of this book is as accurate as possible and acknowledge that any faults or imperfections are mine alone.

As always, I pay tribute to my family for their never-ending love and support; in already mentioning my daughters and their spouses, I naturally include my grandchildren Emma, Jessica and Harry Cowper and Samuel and Annie Grace Jerreat, as well as my sons, Mark and Robert.

Most of all, I salute my wife Ann, who, for over fifty years, has been my dear, loving companion.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Jeff Edwards

Prologue

First Sightings

Fraudsman

Prison Days

Out of Control

On the Run

Escape Plans

The Hunt

The Follow

The Shooting

The Investigation

Enter the Complaints Department – CIB2

Explanations and Recriminations

Enter the Flying Squad

Plotting Up

Capture in the Tunnel

Martin – Centre Stage

Martin’s Trial

The Further Trials

The End of the Road

Rumours and Opinions

Epilogue

Bibliography

About the Author

Also by the Author

Plates

Copyright

Foreword

by Jeff Edwards

Former Chief Crime Correspondent, Daily Mirror, President of the Crime Reporters’ Association

There is no doubt in my mind that Dick Kirby is the all-time best, most successful, and prolific author of ‘real life’ books about the British police.

I like to think that, in a very small way, I helped him on that path.

I first met Dick in 1970. He had just been made a fully fledged detective constable posted to the CID (Criminal Investigation Department) at Forest Gate in East London, and I was a fluffy-faced aspiring 21-year-old crime reporter on the local Newham Recorder. In those days, unlike the situation now, reporters on local papers could get to meet police officers working at busy London police stations easily and without much restriction. Providing you were considered (in CID parlance) ‘a good cock’, who would happily stand his round in the pub and knew how to play by the rules, you were usually welcome.

I instinctively liked most of the cops I met back then. Many of them were outgoing, animated, even flamboyant characters, and I enjoyed their endless stories of life at the sharp end on the mean streets of London. I also liked their bonhomie and sense of comradeship, and their slightly jaundiced and sceptical view of life. Perhaps most of all I liked the dark dry humour and the ready wit many of them possessed.

Newham had one of the highest crime rates in the country at the time and the police were always full of stories. Some of these tales were in the best traditions of Dick Barton or Fabian of the Yard. Sometimes the tales were astonishing and full of daring and courage. Some of them were about skill or cunning where good triumphed over evil. Some of them, to be frank, were where a more acceptable sort of evil triumphed over a worse form. Some of the tales were very tall indeed – and some were unprintable in a family newspaper. Grey areas abounded. I had the time of my life!

I can’t remember exactly where or how I was introduced to Dick Kirby, except that he was one of those whose blend of fierce hatred of criminals, his disdain of weak and ineffectual senior officers and his loathing of devious lawyers and feeble magistrates made him stand out. With a liking for the cut and thrust of lively debate, a sharp wit and pithy observations on life in general, he was never short of an audience. He was a natural-born storyteller. We hit it off and in many ways our careers ran parallel, him moving up to some of the top crime-fighting units at Scotland Yard, while I went on to a long career as a Fleet Street crime hack.

So how do I claim to have helped give a push to Dick’s later career as an author?

In the 1970s almost every police officer I knew was enthralled by the writings of the American author Joseph Wambaugh, who had for many years been a Los Angeles policeman until he turned his hand to writing. What cops everywhere loved about him was his ability to tell it like it really was. On the one hand, it was through compelling documentary stories like The Onion Field, where he drew on first-hand experience of terrible events which affected the lives of close colleagues. On the other, he wrote the candidly observed and extremely funny novel The Choirboys. Wambaugh was the real deal. He knew exactly how street cops thought, spoke, and acted, because he was one of them. In a way, he was their collective voice.

Dick Kirby was one of his greatest fans.

In 1979, as a crime reporter on the London Evening News, I received a phone call from a woman I knew who was working as a publicist for a film company. Hollywood had made a film version of The Onion Field which was to be released soon in Britain. As part of the promotion, Joe Wambaugh was coming to London. While he was here he’d expressed a wish to meet some London police officers. Could I be of any assistance? You bet I could.

The choice was easy. I rang Dick and our mutual chum Peter Connor, another East London police detective, and a dinner meeting was arranged. Needless to say, Dick and Joe and Pete got on famously. And following that meeting I know Dick went on to forge a strong friendship with Joe, which endures to this day.

I have no doubt that Dick was inspired by his American counterpart to take up a second career as a writer when he retired from policing. Although their experiences were separated by the width of an entire continent and an ocean, in my opinion there is something similar in the way Joe and Dick write. You could call it shared experience, but it is more than that.

I believe it is because Dick also has the instinctive ability to translate and describe the subtle nuances in the way real police detectives, real cops on the beat working at the sharp end of law enforcement, think, speak, reason and behave.

The story of David Martin and his crimes is an extraordinary one, which Dick tells here in well-researched detail. Crime reporters, sometimes with tongue in cheek, have often used the phrase ‘master criminal’ to describe well-known villains. I would not call Martin one of those. He was first and foremost dangerous, volatile, ruthless and narcissistic. However, he was, as this book describes, in many ways exceptionally clever and quick of mind. For the police he was a resourceful, determined and formidable foe. In a strange twist, which this book chronicles closely, Martin became as well known perhaps not for what happened to him, but what happened to someone the police thought was him.

The entirely innocent Stephen Waldorf had the misfortune to strongly resemble Martin in appearance. Thus fate conspired to put him in the passenger seat of a car which was being followed through London by an undercover police unit who were looking for David Martin. Because Martin had previously shot and nearly killed a policeman, these officers were psychologically wound as tight as watch springs. Eventually the car, hemmed in by stationary traffic, was riddled with police bullets. Waldorf himself was hit five times and then his skull was fractured with the butt of a detective’s pistol. Astonishingly perhaps, he survived and made a full recovery.

Dick Kirby deals with this seminal moment in modern police history with great even-handedness. His description of the surveillance operation which police thought was targeted on David Martin brilliantly conveys the heart-stopping uncertainty, contradictions and chaos that can occur when even the best constructed plans suddenly run out of control. The reason his account is so compelling is because, once again, Dick demonstrates this sixth-sense knowledge of the way genuine police officers reason and react at times of great tension and stress. Like Joe Wambaugh, Dick Kirby is the real deal. He writes with the insight of someone who can only do so when they’ve lived it and felt it emotionally.

The Waldorf shooting was a watershed for the way British police train and deploy firearms specialists. But as any military man will tell you, few battle plans survive first contact with the enemy, and so it is with the police. If you place deadly force in the hands of anyone, be it well-trained police or ruthless criminals, and add tension and emotion into the mix, it will always be the case that sometimes things will end in catastrophe.

Dick Kirby was a first-class copper and is now a first-class author. Long may he write.

Prologue

I leant back in the rather rickety captain’s chair and gazed around at the shabby surroundings in Harry’s office, from which he ran his scrap-metal business in Hammersmith, until my eyes finally settled on Harry, sitting behind the desk that separated us.

‘I’ll always remember turning over a scrappie’s yard when I was an aid to CID,’ I said reminiscently. ‘D’you what he said to me, Harry?’

Harry obligingly raised his eyebrows, exhibiting a polite modicum of interest.

‘He said, “Let’s face it, Guv – ninety per cent of the gear in here is bent and the other ten per cent’s iffy.”’

Harry gave a blackened, gap-toothed grin. ‘I hope your first-class gave you a bollocking for going there in the first place,’ he replied.

The ‘first-class’ that Harry was referring to was the station’s detective sergeant (first class) who was traditionally in charge of the aids to CID; and it was alleged that some of the first-classes offered a degree of protection to the scrappies in return for a highly unofficial bursary, to save them from the depredations of the feral aids who, it was said, would nick anybody for anything.

But I was able to smile at Harry in spite of the implied insult and I shook my head. ‘Not on that occasion,’ I replied. ‘Because the first-class was with me and I’ll tell you something else, Harry.’ I leaned forward and picked up a rather wide, but weightless, spring-back binder which should have housed Harry’s legitimate business transactions. ‘It’s amazing what you can find if you’re prepared to look for it,’ and with that I dropped it on the table. A thin coating of dust arose from the binder, a mute testimony that little had been added to the file for some time. I added, ‘Or not, as the case may be.’

Harry’s jowly, lugubrious features sagged and he swallowed noisily. ‘Am I going to be turned over, Guv?’ he asked plaintively. ‘Are you putting it on me?’

Abruptly, I stood up. ‘I really don’t fancy looking round the place – not right now, that is,’ I replied. ‘Tell you what – why don’t you and I go and have a drink, and I’ll tell you what I’ve got in mind.’

Harry brightened up immediately. ‘Right!’ he said and off we went to the pub round the corner. I felt fairly sure that Harry had something I wanted and that ‘something’ was the whereabouts of Eric.

This was a classic case of ‘the stick and the carrot’. The stick was the implied threat that if that scrap metal yard was to be searched – as Harry had said, ‘turned over’ – then it was quite probable that some non-ferrous metal of an incriminating nature would be found, which Harry would find perplexing to explain away. Given the paucity of invoices in his spring-back binder, Harry might have had to have accepted, with ill grace, the inevitability of ‘a stretch’ – or, to the uninitiated, twelve months’ imprisonment. But then, almost immediately, I had offered him the far more acceptable compromise of a carrot: the offer of a drink in more salubrious surroundings than his odoriferous office and where Harry could marshal all of his perspicacity to determine precisely what was on offer.

By today’s standards, you may think that this was slightly unconventional policing but this is now and that was on Friday 14 January 1983. Unorthodox or not, that was the way things got done during those halcyon days with New Scotland Yard’s Flying Squad – commonly known as ‘The Sweeney’ and more officially as C8 Department – and now I’ll tell you how I came to be in Harry’s scrap yard.

Over the previous two months, my Flying Squad team and I had effected the arrest of the leader of a highly organised and deeply despicable gang of blaggers – robbers, to you. They had carried out raids on the homes of elderly, wealthy women in the Belgravia area of London and attacked, chloroformed and bound and gagged them before making off with their treasured possessions. Two such raids had resulted in the gang becoming £30,000 richer. Men who make their living by attacking elderly ladies seldom possess much moral fibre and the gang leader was no exception to the rule. I had arrested him, with the aid of that very large officer from Ulster, Gerry Gallagher – of whom you’ll hear much more later – at a quarter-to-two in the morning as he endeavoured to make an escape through the window of a first-floor flat in West London. Not only did the gang leader confess to everything he’d done, he also informed us of robberies that he and his gang had planned to carry out in the future, took us to the venues of these planned robberies and identified each of the other gang members. They were brought in, admitted their respective parts in the individual offences, were charged and were now in prison, on remand.

And to be fair – this is no time for false modesty – it was a terrific case, one in a long line of sensational arrests involving snouts, fast drives across London and punch-ups with seasoned villains. So in this current investigation, everybody was accounted for – everybody, that is, but Eric. We knew who he was but not where he was. Eric, whose criminal career had commenced over twenty years previously, was no fool. He was constantly on the move and if the gang leader had possessed an idea as to his whereabouts, I have no doubt he’d have told us. But he didn’t, so he couldn’t. Therefore, I put the word about and then I got the whisper that if anybody knew of Eric’s address, it’d be Harry the Scrappie.

So that was how Harry and I came to be drinking large scotches on that cold January evening; and it paid off. The address he gave me for Eric was way out in the boondocks and as I bade farewell to Harry, I also made it quite clear that if Eric should receive a warning telephone call of our impending arrival, our next meeting would be not quite so convivial.

In the ordinary run of things, I should have submitted Harry’s name, under a suitable nom de plume, to be considered for an ex-gratia payment from the Yard’s informants’ fund for his valuable input into revealing the whereabouts of a much-wanted blagger, who in the due process of time would share among his contemporaries a total of twenty-six years’ imprisonment. Not on this occasion, though. Harry had profited from not having his business brought under careful scrutiny; it was a case of quid pro quo.

It had gone six o’clock when I made my way back to the Flying Squad car, a nondescript Rover 3500, parked some distance away; my driver, Tony Freeman, was behind the wheel. All squad vehicles were fitted with two-tone sirens, a gong and two radios: the main set could send and receive messages to and from Information Room at Scotland Yard and vehicles all over the Metropolitan Police District (MPD). There was a second, small set, also known as the ‘car-to-car-radio’ and these were used during squad (and other specialist units) operations for contact between the operational vehicles but which only had a limited transmitting and receiving range – about two to three miles. Usually, since the vehicles were inevitably in close proximity to one another, that did not present a problem. As I got into the car, I asked, ‘Anything happening on the air?’

Tony shook his head. ‘A right load of that CB1 crap on the main set,’ he replied, and then he added, ‘Funny thing, Dick. I think C11 must be nearby. I heard them on the small set a little while ago – all of a sudden, I heard someone say, ‘‘Oh, fuck!’’ Dunno what it was all about.’

‘Nothing else since then?’ I asked and Tony shook his head. ‘Right, let’s head back to CO,2 see if anything’s happening.’

Tony dropped me off on Scotland Yard’s concourse and I got into the lift and ascended to the fourth floor, Victoria Block, pushed open the swing doors, turned left and walked down to the end of the long corridor (Flying Squad offices on the left and C11 – or Criminal Intelligence – on the right) towards the main squad office. There was no one about; it seemed that they’d heeded the wise police dictum: that it was POETS3 day.

There was just one person in the squad office: Jim Moon, once an ace squad driver, now in retirement supplementing his pension by manning the telephones and the radio.

‘Anything happening, Jim?’ I asked but Jim shook his head. ‘Nothing for you, Sargie.’

I picked up the Police Almanac which housed the telephone numbers for all the police stations in all the United Kingdom’s different constabularies, found the one covering the area where Eric was living and asked the local detective inspector to nab him for us. ‘That’s great!’ responded the Inspector. ‘We want the little bugger as well, but we didn’t know where he was!’ Of course, the Inspector hadn’t made the acquaintance of ‘Harry the Scrappie’.

I booked off duty and went home to Upminster, Essex, rescued a steak pie from the oven, which, had I arrived home three hours previously when it had been freshly cooked, would have been quite tasty, made incisions into it to release the scorching heat and poured myself a glass of red. As I finished the meal, I poured myself another glass and then I realised it was time for the news. I switched the television on. There on the screen was a yellow Mini, registration number GYF 117W, its doors wide open, spotlights illuminating it and the commentator was saying, ‘A man has been critically injured in a police ambush in a West London street in what may be a case of mistaken identity. Witnesses said marksmen surrounded a car in a traffic jam in Pembroke Road in Earls Court and opened fire.’

Just then my wife Ann came into the room. ‘Is this what made you late?’

I shook my head. ‘No, first I’ve heard about it … shh … I want to hear …’

‘The driver was shot several times in the head and body,’ continued the commentator. ‘Scotland Yard said the ambush was part of an operation to recapture escaped prisoner David Martin.’ Now the camera focused on one of the first witnesses on the scene, secretary Jane Lamprill, who said the man seemed very badly injured. ‘He was about thirty,’ she said, ‘but I couldn’t even see the colour of his hair because of the blood.’

‘Christ!’ I exclaimed. ‘The wrong bloody man!’

‘No, they said it wasn’t clear if it was this Martin man or not,’ said Ann, but just then the phone rang. It was the Inspector from the constabulary to say that Eric had been arrested. ‘He’s singing like a bird to our job,’ he chuckled, ‘although he did look a bit worried when I said the squad wanted to have a word with him!’

‘He fucking needs to be!’ I scoffed. ‘Just lock him up tonight and we’ll be along to see him tomorrow morning.’ I rang off and telephoned the rest of the team for an early start the following day. As I went up to bed, the name ‘David Martin’ was going round and round in my head. Who was he? All right, it was a fairly common name but where the hell had I heard it before?

The next day, Saturday, Tony and I, together with the rest of my team were heading north out of London. We reached our destination, a small market town in the middle of nowhere, where I met, and spoke fairly briskly to Eric who promptly confessed everything confessable in a written statement. The constabulary officers wanted to charge him with their offence, take him before the local Magistrates’ Court and remand him in custody and this suited me to the ground. Later, we could have him produced on a Home Office order to join the rest of the gang on a remand hearing at our Magistrates’ Court and then we could commit the whole lot of them to the Old Bailey for trial.

We set off back to London and I was glad that the ‘Eric’ business had been transacted so quickly. Today was my mother’s 78th birthday and since my father had died four months earlier, it was especially important for me and the family to be with her at this time.

As we reached the borders of the Metropolitan Police District, I called up the Flying Squad office on the RT set: ‘Central 899 from Central 954; Jim, book us back in the MPD, please – see you soon.’

The reply was immediate: ‘Central 954 from Central 899; get over to ‘Delta Delta’ as quick as you can – there’s a flap on!’

I acknowledged the call as we came out of the Hanger Lane gyratory system and on to the A40. ‘Delta Delta’ – otherwise Paddington Green police station and ‘D’ Division’s Divisional Headquarters – was just a short distance away; and as we tore towards the A40(M), two-tones wailing, I was thinking, ‘Why Paddington? Why us?’

All was soon revealed. The nick was crowded with police officers, a lot of them Flying Squad. It was from ‘D’ Division that the operation had originated to hunt down David Martin, who, charged with shooting a police constable, had escaped from custody. Somehow – nobody seemed quite sure how – matters had gone tragically wrong and had resulted in armed police shooting and seriously wounding an innocent young man, a 26-year-old film editor named Steven Waldorf. One of the officers who had fired shots which had injured Waldorf was attached to ‘D’ Division.

Morale at Paddington Green police station was, quite understandably, at rock bottom and the operation, which had been headed by ‘D’ Division’s Detective Superintendent George Ness, was now, on orders from on high, being handed over to Commander Frank Cater who the previous week had taken over the running of the Flying Squad.

My team and I were part of 12 Squad, which along with 10 Squad was now appointed to the investigation. The officer in charge of operational matters was Detective Chief Superintendent Don Brown, who I later discovered was a seasoned and highly respected squad officer. Arriving on the same day as Frank Cater, Brown had returned to the Flying Squad for his third and final tour.

I didn’t know Don Brown but I knew Frank Cater; he’d been my boss when I’d served on the Serious Crime Squad and as the meeting broke up he murmured to me, ‘We need to wind this up as soon as possible, Dick.’ I nodded and replied absently, ‘Right, Guv,’ but my mind was on other matters – from the photographs and the background I’d seen and heard of the target, I’d just realised where I knew Martin’s name from. The Flying Squad hunt for David Martin was beginning right now, but my private war with Martin had started ten years previously.

1. Citizens’ Band radio, a mercifully short-lived fad whereby amateur radio enthusiasts searched the airways to speak consummate gibberish to complete strangers.

2. Commissioner’s Office, New Scotland Yard.

3. Piss Off Early, Tomorrow’s Saturday.

Note: The correct spelling of Steven Waldorf’s name is with a ‘v’ despite many online resources and newspapers spelling it with ‘ph’.

First Sightings

Before I progress any further with the story of both the shooting of an innocent man and the hunt for a man who was anything but innocent, I have to introduce you to the police world of many years ago and of which I was a member.

In the early 1970s, I was appointed a detective constable of the Metropolitan Police and was posted to Forest Gate police station in the East End of London, reputedly the busiest sectional station in the Metropolitan Police. I couldn’t have been happier. I’d had a successful career as an aid to CID, plus I’d scored high marks at the ten-week Initial (Junior) Course at the Detective Training School. In addition, I’d achieved the highest number of arrests on ‘K’ Division and now, having successfully passed two stiff selection boards, as a fully fledged member of the Criminal Investigation Department I needed to make my bones as a detective. The whole area (it was colloquially referred to as ‘The Manor’) – Forest Gate, Upton Park and Manor Park – was a hotbed of villains and villainy and I simply couldn’t wait to get stuck into them.

As an aid to CID, our brief had been to get out and patrol the streets, keep observations, follow, stop and arrest suspects and cultivate informants. Now as a member of the CID proper, I investigated reported crimes and attended the Magistrates’ Court practically every day; it was a kind of mini Stock Exchange, filled with the flotsam and jetsam of society, where deals were struck, promises made, informants procured, prisoners remanded and evidence presented. The rest of the time I was attending Crown Courts, meeting informants, typing reports, searching suspect premises and arresting burglars, robbers and fraudsmen. There were simply not enough hours in the day; and at this time the CID were not paid overtime. So much was going on that if I was unable to immediately arrest a local suspect, I’d leave word with their friends and relations for the culprit to surrender at the nick at a specified time, and they usually did.

Right from the start I tore through the underworld like a dervish. I arrested four tearaways wanted for grievous bodily harm, caught one of the last, great cat burglars and his receiver and broke up a highly unpleasant gang of half a dozen blackmailers. A husband-and-wife team were wanted for fraud all over the country; I received a tip that they were about to leave their hotel in the Romford Road and raced down there just in time to stop them in their car, which was loaded with swag. An Arab sheikh in full tribal regalia who was carrying out a fraudulent transaction in a bank was surprised to be seized, addressed as ‘cock’ and unceremoniously bundled into my car, and when I was attacked by two young thugs whom I’d arrested for possessing offensive weapons, I was restless while on sick leave to return to duty so that I could get out to nick some more. This, as you will imagine, played havoc with my home life. It’s a small miracle that Ann and I are still happily married after fifty years.

I reached for the ringing telephone in the CID office on that particular Monday morning; it was the manager of a jeweller’s shop in Green Street, to tell me that a man was at the premises attempting to purchase goods by means of a stolen credit card. I slammed the phone down and, shouting at another detective constable to follow me, I raced down the stairs to the station yard where my car, a powerful Ford Corsair 2000 GT, was parked. We roared out of the yard, turned right into Finden Road and almost immediately left into Green Street. ‘You’ll break our necks, the way you’re driving,’ sighed my companion, who was not entirely fired with enthusiasm for this investigation, as we tore south along the thoroughfare, paying only lip service to the restrictions imposed by the Road Traffic Act. ‘He won’t be there,’ he insisted. ‘As soon as the manager went to phone, he’ll have been long gone.’

Privately I too thought that this might be the case but while a possibility of catching a fraudsman red-handed existed, I wanted to give it my best shot. Pulling up outside the jewellers, I ran towards the shop entrance and as I did so, a young man started to leave. There was absolutely nothing about him to attract suspicion; he was extremely smartly dressed in a pinstripe ‘company director’ style suit, slim, about five feet nine, dark blond hair, a slight tan, aged in his mid-twenties and looked entirely unconcerned as he courteously stepped to one side to let me enter the jewellers. He then began unhurriedly scrutinising the wares in the shop window in the same way that any discerning customer who had yet to make up his mind might do.

I rushed up to the manager. ‘Right, where is he?’ I demanded and given what was to happen, I now realise that a courteous, more structured approach might have been called for.

The manager raised his eyebrows. ‘To whom are you referring?’

‘The bloke with the stolen credit card,’ I testily replied.

‘And you are?’ he enquired.

‘Police from Forest Gate,’ I replied, and I was getting quite irritated because by now, it was obvious that the suspect had departed before our arrival and this was the manager’s way of putting me in my place for not getting there sooner.

Nodding thoughtfully, the manager asked, ‘Have you any – er – identification?’

I snatched out my warrant card which the manager ostentatiously examined before nodding his approval. ‘Right – now was it you I spoke to on the phone at Forest Gate police station about five minutes ago?’ I asked. He conceded that this was so.

‘And did you tell me there was someone in the shop trying to buy goods with a stolen credit card?’ Again, with pursed lips, he nodded in agreement.

‘So how long ago was it that he left?’ I asked.

The manager languidly waved in the general direction of the door. ‘He went out,’ he replied, ‘just as you came in!’

‘You wanker!’ I roared, turned and rushed out of the shop, looked left, then right, just in time to see a pair of well-tailored trouser legs disappear round the corner into Plashet Grove.

As I dashed up to the junction, I heard the roar of a powerful car engine starting up. Turning the corner, there facing me was a Jaguar XJ-12 with the fraudsman behind the wheel. As I ran towards the car, I noticed that the car’s front passenger window was open, so I plunged in, hoping to grab the ignition key. With that, the driver slammed the car’s automatic transmission into ‘drive’ and drove off fast, with me half-in and half-out of the vehicle.

I said afterwards that I’d be able to recognise him again because of the imprint that my knuckles made on the side of his face, but don’t you believe it. As pugilists reading this are aware, to effectively deliver a straight right, you need the transference of power, driving off the ball of the right foot and turning the hip and shoulder in the direction of your opponent. You try it when you’re lying horizontally, clinging on to a speeding car with one hand! Yes, I gave him a dig but what with the lack of force of the punch, plus the rush of adrenaline he must have been experiencing, it had little or no effect.

As he reached the junction with Green Street, he braked sharply and I was thrown from the car. I rolled over in the roadway a couple of times and as I got to my feet, I heard the furious sounding of car horns and saw the Jaguar swerving crazily across the junction with Green Street and then swing left into Plashet Road. I dashed across the junction but by the time I got to Plashet Road, the car had vanished. It was only later that I discovered that the Jaguar – which had been reported stolen from the Paddington area – had been abandoned in Lucas Avenue, the fourth turning on the left. It was thought that the driver – who had discarded his jacket, to prevent recognition – might have escaped by turning left out of Lucas Avenue into Harold Road and thence the short distance into Upton Park Underground station.

I was furious – furious with the manager of the shop, furious with the fraudsman who could have caused me serious injury and furious with myself for failing to arrest him, by not being quicker off the mark. Matters were not improved when I limped back to the police station where, with a commendable lack of tact and concern for my well-being, the first-class sergeant scoffed, ‘Huh! Couldn’t catch a bleedin’ cold!’ Doc Lazarus MBE, the Divisional Surgeon (who would later say that he thought that I was his best customer), tut-tutted as he examined my lumps and bumps from being thrown off the car, diagnosed strained chest muscles from hanging on to it, prescribed paracetamol and told me to ‘get on with it’.

So I did. Simmering quietly, I put the details in the crime book, circulated details of the fraudsman and the details of the card he’d been using and cracked on with a fresh inquiry.

Months later, I received notification that the fraudsman had been arrested somewhere else in London and had been charged with a whole series of offences; when he appeared at court, he had been sentenced to a long term of imprisonment.

I looked at his name. Martin. David Ralph Martin. Aged 26 and born in Paddington. Never heard of him. And he wasn’t a local lad. So how did he know about Lucas Avenue and the close proximity to a secondary getaway route via Upton Park station? Had he taken the trouble to plot an alternative escape, prior to going into the jewellers, just in case he got tumbled? And what was more, I couldn’t get out of my mind the slick way in which he’d strolled out of the shop; that took a lot of nerve.

Then I shrugged my shoulders and forgot about him.

I might have thought that I was cock-o’-the-walk in the CID office at Forest Gate but I still had a lot to learn about criminal behaviour and psychology in general, and crooks like Martin in particular. Slick? Christ, I didn’t know the meaning of the word.

Fraudsman

From undistinguished beginnings, David Martin’s life can only be described as extraordinary. He was born in Paddington on 25 February 1947 and was brought up in a council flat in Finsbury Park, the only child to Ralph and Joan Martin. For all of his life and whatever he did, right or wrong, his father defended, made excuses for and idolised him. Father and son had a common predisposition: both of them hated the police.

In common with the majority of law-breakers, Martin’s criminal career commenced during his formative years. He first appeared at North London Juvenile Court on 19 April 1963 where, for unauthorised taking of a motor vehicle and associated offences, he was fined a total of £4 and was disqualified from driving for twelve months. Less than three months later he was back at the same court, for stealing petrol from a car. On this occasion, he was fined £5 and his father was bound over in the sum of £15 for twelve months to ensure his son’s good behaviour. And it appeared to work. Two years went by and the twelve months, both for Martin’s disqualification from driving and his father’s recognisance, passed without incident.

But this changed in June 1965 when he appeared at Bow Street Magistrates’ Court. For threatening behaviour and assaulting a police officer outside a club ‘without realising who he was’, as he would later say, he was sentenced to three months in a detention centre.

Martin was not well educated but he was highly intelligent and he had a natural ability to turn his hand to anything electrical or mechanical; following his release from detention in September 1965, he trained as a motor mechanic. It did not last long; within five months he appeared at Highgate Magistrates’ Court, where for stealing items from his employer, he was placed on probation for two years. And that was the end of any pretence of honest work for a thoroughly dishonest employee; he ignored the counsel of his probation officer and from then on, Martin would channel his expertise into matters purely criminal, especially stealing cars.

It caught up with him in July 1967 when at the Middlesex Area Sessions, for obtaining property by false pretences, three cases of larceny, two cases of storebreaking and stealing a car – and requesting twenty-one other cases to be taken into consideration – he was sentenced to Borstal Training and disqualified from driving for five years.

During 1968, 1,425 inmates escaped from Borstal; Martin was one of them. He sprang a lock, scaled the boundary wall and was away. It was some time before he was caught and during his unofficial parole, he had been busy. He had taken a car without the owner’s consent and that, plus dangerous driving, driving while disqualified and stealing items, including a .22 starting pistol which he put to good use by producing it with intent to resist arrest, resulted in him being returned to Borstal Training when he appeared at the Inner London Quarter Sessions in November 1968. He also asked for a further twelve other offences to be taken into consideration from while he was on the run.

To those unaware of the term, the now redundant Borstal Training was a period of incarceration of between six months to two years awarded to young offenders in the often forlorn hope that they would receive reformative training. Martin was one of that forsaken number; he served the full two years.

As soon as he was released, Martin plunged once more into criminality. Appearing at West London Magistrates’ Court, he was committed to the Inner London Quarter Sessions for sentence in December 1969 and, for two cases of obtaining goods by means of a forged instrument, handling stolen goods, theft from a vehicle, unauthorised taking of a vehicle and driving while disqualified, he was sentenced to a total of twenty-one months’ imprisonment and disqualified from driving for a further twelve months.

Released on 27 January 1971, that was the last occasion that Martin would plead guilty to anything; in fact, as will be seen, he wouldn’t plead not guilty either. His ego was going into orbit. His passionate loathing for those in authority, particularly the police, was developing and in addition, a life-long fascination for locks and security devices began to evolve.

He gathered associates around him and his future criminal enterprises would display enormous cunning and sophistication for a young man, still in his mid-twenties. David Martin was simply going to take on the establishment.

Eddie Roach had joined the Metropolitan Police in 1955. He had worked at St John’s Wood, Albany Street and Paddington Green and after a stint with the Metropolitan and City Company Fraud Department, he was promoted to detective sergeant and posted to Hampstead police station where he ran a very successful crime squad.

In September 1972, due to a sudden upsurge in crime in the neighbourhood, the divisional commander of the area covering the wealthy properties in Hampstead, Swiss Cottage and West Hampstead decided to create a crime squad, consisting of ten temporary detective constables (the successors to aids to CID), ten uniform police constables working in plain clothes and a uniform sergeant. Due to Roach’s undisputed success of previously running a crime squad on ‘E’ Division, he was the natural choice to head the squad. The commander gave Roach complete authority in selecting his staff, told Roach to report to him directly and provided an office for the squad at West Hampstead police station, which had just been opened that year at 21 Fortune Green Road, West Hampstead, NW6. Roach would later say, ‘Detective work is fifty per cent common sense, forty percent dedication and ten percent luck.’ The squad commenced its duties on 25 September 1972 and would demonstrate all those investigative attributes in the months which followed.

About a mile to the south of the police station was Langtry Road, NW8, a cul-de-sac just off the junction with Kilburn High Road and Belsize Road. A few days after the formation of the squad, two officers spotted a red BMW 30 CSI parked outside No. 3 Langtry Road. The model was new; only eight of them had been imported into the United Kingdom from Germany. A check revealed that over a week previously on 18 September, a young man had gone to BMW Concessionaires Ltd in Chiswick High Road and had asked for a test drive. He must have possessed an air of plausibility because the management permitted him to do just that; he was handed a key, drove off and vanished. The credible young man was, of course, David Martin but the officers were not aware of that, nor that he was now residing at 3 Langtry Road. The vehicle, which had been allocated registration number LOY 4K, currently bore false plates.

In fact, this vehicle had already been the subject of a high-speed chase where police vehicles, headed by an ace area car driver, Police Constable Mike McAndrew, had lost the BMW. Given Class I and II police drivers’ advanced training at Hendon Driving School, this hardly seemed possible but the explanation was provided by one of Roach’s investigating team. ‘He was quite fearless in high-speed motor chases,’ Colin Black told me, ‘and said during interview that if a police car was coming in the opposite direction, he knew they would move out of the way because they didn’t want to get killed; he didn’t have any fear of death.’

The vehicle was now kept under observation by the police, after they had surreptitiously deflated one of the tyres to prevent the thief from returning and driving off in it. However, the police were unaware that the thief, from the comfort of 3 Langtry Road, was keeping them under observation.

After twenty-four hours, during which time Martin had prudently not approached the BMW, the police brought a low-loader to Langtry Road and conveyed the car to West Hampstead police station where it was placed in a bay beneath the CID office, booked in and the owners informed. What the police did not know was that Martin had followed the low-loader to its destination.