9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Dixie Deans is a true Celtic legend. Between 1971 and 1976, he scored 132 goals in 184 games and was part of the great Celtic team that swept to nine consecutive Scottish league titles and dominated a golden era of the national game. Dixie cemented his status in football folklore by becoming the first Scottish player to hit hat-tricks in two cup finals, but he is remembered just as much for the special bond he struck with the fans - ties that remain as strong today, exactly 40 years after he first signed for Celtic from Motherwell. Now Dixie, a member of the Celtic Hall of Fame, opens his scrapbook of memories on a lifetime of adventures in the beautiful game of football. From the struggle of growing up in a one-parent family to losing his beloved mother just as his career was starting to blossom, to playing under the legendary Jock Stein, and alongside the likes of Dalgleish, Macari, McNeill and Connolly, Dixie recalls the tumultuous days of a roller-coaster career at the very pinnacle of Scottish football. This is a fascinating story, at times uplifting, heartrending, inspiring and haunting, proving that there really is only one, inimitable, Dixie Deans.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

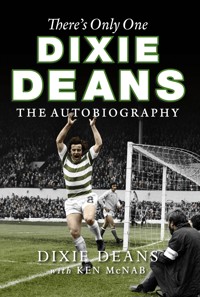

There’s Only OneDIXIE DEANS

There’s Only OneDIXIE DEANS

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY

DIXIE DEANS

with

KEN McNAB

First published in 2011 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House 10 Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © John Deans and Ken McNab 2011

The moral right of John Deans and Ken McNab to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 028 9 eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 083 8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore Printed and bound by MPG Books Limited, Bodmin

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preface

Chapter One

In the Beginning

Chapter Two

Growing Pains

Chapter Three

Dixie of the Farmers’ Boys

Chapter Four

Mum’s Gone

Chapter Five

Well Chuffed

Chapter Six

Beating England and Banksy

Chapter Seven

Signing for Celtic

Chapter Eight

When We Were Kings

Chapter Nine

Penalty Villain

Chapter Ten

Hat-trick Redemption

Chapter Eleven

The Big Man

Chapter Twelve

Snubbed by Rangers

Chapter Thirteen

A Grand Old Team

Chapter Fourteen

Jinky

Chapter Fifteen

The Bubble Bursts

Chapter Sixteen

The Cap Doesn’t Fit

Chapter Seventeen

The Year From Hell

Chapter Eighteen

Full Time at Celtic

Chapter Nineteen

England Here I Come

Chapter Twenty

Wizard in Oz

Chapter Twenty-One

Big Trouble Down Under

Chapter Twenty-Two

Wearing it Well at Wembley with Rod

Chapter Twenty-Three

Back at Celtic

Chapter Twenty-Four

Bhoyhood Ambition

Index

Acknowledgements

Dixie Deans would like to thank his wife Pat and their family for all their support during the years and to all the fans who have cheered him on from the terraces.

Ken McNab would like to thank his wife Susanna and their children, Jennifer and Christopher, and all the Porter clan. Grateful thanks are also due to the following people who helped with this project: Rosemary O’Hare at the Mitchell Library, Kevin Turner on the Evening Times picture desk, Tony Murray, Bruce Ross, Tony Carlin, Celtic Football Club, Max Huffa in Adelaide, Robert Reid at Partick Thistle, Roger Wash, historian at Luton Town Football Club, Richard McBrearty at the Scottish Football Museum at Hampden Park, The Scottish Daily Record and Sunday Mail picture desk, the Evening Times sports desk, Jim McCann and Jeff Holmes at Scottish News and Sport, Peter Burns and Neville Moir at Birlinn and, of course, to Dixie.

Preface

‘Dixie Deans.’

The announcement was loud and clear. Definitely my name, definitely Dixie. There was no mistake. Except I couldn’t quite believe it. Mine was the last name I expected to see flashed up on the big screen on the stage at The Moat House Hotel, especially when I looked around and saw the likes of Jinky, Big Billy, Davie Hay, Tommy Burns, Lubo Moravcik, Paul McStay . . .

And the roll call of honour also included John Thomson, Charlie Tully, Jimmy McGrory, heroes in Hoops from a bygone age.

‘Dixie Deans.’

Next thing I’m being slapped on the back and the guys at the table are shaking my hand. Beside me, Tommy Callaghan turned and said: ‘Well done wee man, you really deserve it.’

Everything seemed to happen in slow motion but gradually the realisation of these two words dawned. I remember the clapping and the cheers that erupted after every other name that was read out. But when it came to mine, I was almost too shocked to notice.

‘Dixie Deans.’

I probably swore. In fact, I’m bloody sure I did. And the second word was . . . me. Sorry, but I think a little Anglo-Saxon was totally understandable. After all, it’s not every day that you join an elite band of brothers, every one of whom has earned the right to be called a legend. Not every day that you’re inducted into Celtic Football Club’s inaugural Hall of Fame along with 24 other former players.

When I look back on that moment today, my chest still swells with pride. It was a real high spot of my life. Hand on heart, when I accepted an invitation to go along, all I expected was a swally and the chance to catch up with some old pals. Believe me, I was more than happy to be a supporting actor instead of a leading man. And you’ll understand why when I reel off the other names standing tall beside my own – Pat Bonner, Willie Wallace, John Clark, Billy McPhail, Jimmy Johnstone, Joe McBride, Ronnie Simpson, Paul Lambert, Bobby Collins, Jimmy McGrory, Patsy Gallacher, Tom Boyd, Stevie Chalmers, Neil Mochan, Lubo Moravcik, Charlie Tully, Paul McStay, Danny McGrain, Billy McNeill, Murdo MacLeod, Sean Fallon, David Hay, Bobby Collins and Tommy Burns.

Each and every one of them a part of Celtic folklore. And now, in 2001, I was officially a member of the same company. Hard to believe, really, even more so when you think of some of the names who should be there . . . Dalglish, Larsson, Quinn, Connelly, to name a few.

This meant the world to me because it was voted for by the guys on the terraces, the diehards who turned up in all weathers to cheer on Celtic. The fans with whom I always tried to have a special connection. I like to think I always wore my badge on my sleeve – at Motherwell AND Celtic, incidentally – and that my wholehearted approach to playing football struck the right kind of chord with the punters.

I never tried to kid anyone. I wasn’t a Pelé or a Bestie. I wasn’t even a Jinky . . . as Jock Stein often liked to remind me. I was just plain Dixie and my job was to score goals that won football games, that hopefully won cups, that hopefully won league titles.

Now here I was, officially a first-time Celtic Hall of Famer. Never in my wildest dreams did I ever expect this to happen to me, a boy from Linwood. But it’s at moments like these that you look back on your life and wonder: ‘How the blazes did I get here?’

Even now I’m not really sure, but let me tell you it’s been one hell of a roller-coaster, full of amazing twists and turns, highs and lows from Neilston to Fir Park, from Paradise to Australia. A life of blood, sweat and – mostly – cheers.

The year 2011 will mark the 40th anniversary of me signing for Celtic, as good a time as any to look back on what you might call my scrapbook of madness. And when I flick through the pages, I can hardly believe the names of the guys I played with, the success we had as part of what I genuinely believe was a golden era for Celtic, and the goals I scored.

Goals. That was my game in a nutshell. And I’m proud to have banged in 132 in 184 games for the Hoops – not a bad tally, I hope you’ll agree. Some of these strikes clinched titles during the club’s fabulous nine-in-a-row era. Hat-tricks in two national finals will always be a huge source of pride. Six strikes in one game against Partick Thistle also guaranteed me a spot in the Celtic history books. And then there was the day I signed on at Parkhead – and tried to muscle a signing-on fee from Big Jock. Not even the thought of my penalty miss against Inter Milan – a nightmare moment if ever there was one – can tarnish my memories.

Football has been my life and that autumn night when I entered the Celtic Hall of Fame was the undoubted high point. I wrote this book partly to reflect on a time when the game really did strike a fanfare for the common man and to remind younger supporters that, you know, teams in those far-off days really could play. And the achievements speak for themselves. This is not a blow-by-blow account of every game I ever played or every player I rubbed shoulders with. Nor is it meant to unlock a cupboard containing lots of skeletons. No, this is mainly about the fitba. Martin O’Neill once summed up football as being about those who play and those who pay – and I would go along with that. So pull up a chair, put your feet up and join me as I look back on my adventures in football.

The following chapters are not just a biography; they are the snapshots that I hope capture my adventures in football and my life. I hope you’ll enjoy a Bhoy’s own story.

Dixie Deans Winter 2010

Chapter One

In the Beginning

In the beginning . . . my name was John Deans. Oddly enough, it still is. That might come as a shock to everyone who knows me as Dixie. But that’s what it says on my birth certificate and that was my name all the way through my childhood and my early teens. It even says it on my passport so it must be right.

And, actually, I’ve always been pretty proud of being John Deans. Nothing fancy, just plain John. But it has always struck me as a good name to have. Honest, decent, a bit gritty and, most importantly, down to earth. And the older I get, the more I feel that about John Deans. My brothers and sister always called me John and so does my wife Pat when she doesn’t call me other things, not all of them as nice as John.

Not that I have anything against Dixie. It’s a name that’s been my ticket to the kind of fame that a working-class boy like me could only have dreamt about. Football has taken me all over the world and everywhere I go Dixie has been my calling card and I’m always grateful. A few years ago a daft rumour went round that I didn’t like being called Dixie any more. The story was I wanted fans and punters in the pub to call me John, if you don’t mind.

Can you imagine a guy like me looking down his nose at anyone? Complete garbage. Would I have called one of my pubs Dixie’s if I hated it? I love being called Dixie and I always will.

But I also reckon it’s important to remember who you are and where you came from. And I was born John Kelly Deans on 30 July 1946, in Thorn Hospital, a no-frills cottage maternity just outside Paisley that only had about 40 beds.

I was named after my father and the Kelly part was a sentimental nod to my maternal granny’s Irish background, but I’ve rarely had reason to use it. Again, though, as you go through life, some of these things become that little bit more interesting in a nostalgic kind of way.

My mum’s name was Kathleen and her maiden name was McCumiskey and she was the centre of my world. Memories of my father are somewhat harder to pick out because he died at the age of 26 from tuberculosis – a horrible illness that would later come back to haunt me and my family with devastating consequences – when I was just four years old, too young to form any proper lasting impressions but old enough to slowly suss out that suddenly there was a gaping hole in all of our lives.

I was the second of four children following on from my older brother James, my sister Kathleen and my younger brother Robert.

Home was Linwood, a village 14 miles west of Glasgow that bordered Paisley, the industrial town – now bathed in city status – famous for its abbey, its textile industries and, of course, St Mirren Football Club.

The 1940s and 1950s were tough decades for anyone to raise a young family and the Deans were no different. Linwood may have escaped Hitler’s bombs but, like dozens of industrial towns the length and breadth of Britain, we felt the aftermath of a war that had brought the country to its knees.

Money was scarce and food was still largely rationed until the country got back on its feet. There was a lot of ill health, especially in places where large families were still shoehorned into Victorian tenements or one-up, one-down houses, some with outside toilets. Made you wonder sometimes who actually won the bloody war. Jobs and a regular income were hard to hold on to but Linwood was perhaps luckier than most. Even before the war, it had enjoyed a thriving power-house background thanks to local textile mills, car plants and carpet factories such as Stoddard’s. By all accounts, my dad was one of the lucky ones. He had a regular payday from a local paper mill where he worked as a labourer. We lived at 12 Moss Avenue, Linwood, a semi-detached house with a front and back door which even today looks quite grand. We were a working-class family and bloody proud of it, and this house, in a quiet street on the edge of town, was always a comfort blanket throughout my childhood.

Don’t think, though, that I lived on easy street – I didn’t. Far from it. I have no great memories of birthdays, for example, being particularly special. But as children you just accept what life has to throw at you and you get on with it. My earliest memories are of being part of a warm, loving family unit. But all that changed even before the forties had ended when my dad died from TB. It was rampant in and around the west of Scotland. You look back and it seems that everyone knew someone who had this hellish lung disease. To be brutally honest, I can’t remember much about his death or too much about the man himself. The missing pieces have over the years been joined together by family and friends. What I do know is my dad was what they euphemistically called a character. In other words, he was a typical working-class man who liked a drink and a smoke and did his best for his wife and kids. I’m told that locally he was known to be ‘handy’ – in other words he wasn’t slow to let his fists do the talking should the need arise. A man’s man, I suppose, a bit of a hardcase, especially having been in the army during the war. Nothing wrong with that; you had to be tough to survive those tough times. The other thing is that my dad came from Johnstone and my mum was from Linwood so he would have had to deal with a bit of territorial aggro as well. He would unquestionably have seen himself as the head of the family, the person whose job it was to put bread on the table, no matter how difficult the circumstances.

I may hardly have known him but you can’t help thinking what if . . . what if he had been around during my childhood . . . what if he had been there to guide me through my teenage years . . . what if he had seen me dedicate myself to football . . . what if he had seen me playing for Motherwell and Celtic . . . what if he had seen me turning out for Scotland? What if he had seen his grandkids thriving?

All these questions that can never be answered. I’m not being maudlin here but it’s inevitable that your mind drifts into those areas occasionally. I’ve sometimes felt cheated by not having a dad there for the big moments. Life can be hard enough without having to travel its path without a father. Fate, however, wrote a different script for my life. I can’t even remember him holding me close or anything like that. Who knows, maybe he wasn’t that kind of guy. I’m sure he did but it would be nice to be able to have a mental snapshot of something like that in my head. I don’t even have a photograph of him. On the whole, however, I’ve never been one for looking back.

After my dad died, it was all about keeping your head above choppy waters. Survival became my mum’s stock-in-trade as she came to terms with the grim reality of bringing up four kids without a husband and without a regular income. She was a striking woman who put her family’s needs first at all times. She didn’t work the nine-to-five but she did odd jobs whenever she could to make a few extra quid and ensure her kids were well fed and well turned out. Definitely, she would have survived largely on very little to save us from sheer desperation and destitution. My brothers and sister, like thousands of other breadline kids, got used to hand-me-down clothes, basic foods and a life of battling upstream. My mum, though, had that wartime spirit, that sense of swimming against the tide and staying afloat against all odds. Christ knows it was tough for her but, although she had every right to feel life had dealt her a crap hand, she never complained. In return, we all loved her unconditionally. She had a very strong support network. Both my grannies lived nearby so it wasn’t uncommon for myself and one of my brothers to stay with one grandparent while the other two went to the other one. As much as anything, it gave my mum a break from running after us all the time. And it ensured that we, as children, grew up understanding the important value of a wider family background. You can also throw into the mix a whole clutch of aunts and uncles and it’s easy to see why I have, by and large, fond memories of my early childhood when perhaps I would have good reason to look back on those days through the cracks in my fingers. We had an open front door and there were always people coming and going. I learnt from an early age how to talk to people of all ages.

My earliest memories, though, are frustratingly hazy. As time goes by, your mind starts to play tricks on you. That’s why it’s difficult to latch on to something and keep it there in my mind’s eye.

But I don’t have to reach far into my subconscious to remember playing football. All I have to do is close my eyes and I can still see myself kicking a ball outside that house in Moss Avenue. Next door lived a guy called Danny McColgan, a wee bloke who owned his own trucking business. He was a huge Celtic man and he was over the moon years later when I signed on at his beloved Parkhead. His boys were roughly the same age as me and my brothers so we used to spend every moment of daylight playing football together round the back gardens.

Those gardens, let me tell you, took some punishment. It wasn’t long before there was hardly a blade of grass left, we had kicked it bare. So then we had to go and play on the spare piece of ground at the bottom of the road. The neighbours often gave us a fair bit of leeway even though there was the usual council sign saying no ball games allowed. Stuff that. Where else could we play?

Of course, not everyone was happy about it, especially when the odd ball went whizzing past a window or we trampled through some garden flower beds to get it back. So sometimes a gruff police sergeant would arrive to feel your collar and it would be a case of: ‘Move along boys.’ If you think about it, though, it’s virtually a rite of passage to noise up the neighbours by playing football. Even at a tender age, my life was all about football. If we couldn’t find a spare piece of ground locally, we used to head up to one of the nearest woods and throw down our jackets as makeshift goalposts. It didn’t do much for our ‘jaikets’ but it gave us a sense of freedom that today’s laptop generation can scarcely imagine.

School for me was just the bit that filled your day until you could get home to kick a ball again. From the age of five, I went to Linwood Primary and I still can see in my mind’s eye the tears running down my cheeks as I saw my mum walk away from the school gates on my first day. There was none of this taking the child right into the classroom and letting them settle in until you slowly retreat into the background. Then it was very much a case of dropping you off and letting you get on with it. My mum, like any other parent, kept telling me how much I would enjoy school. Well, she got that wrong. I hated that first day and, to be honest, I pretty much hated all the bloody rest as well.

Right from the start, I wasn’t cut out for school. When God was dishing out brains for education, I readily admit I was in the shallow end of the gene pool. Hands up, I’m the first to confess I had a roguish streak in me even from a young age. I wasn’t a bad kid but I was definitely show-offy and perhaps a little too quick to shoot from the lip. A smart arse, if truth be told. But when I think of it now my rebellious streak was probably a defence mechanism. I was never going to challenge Einstein but I made up for it by trying to be the life and the soul of whatever was going on. And, in those days, I reckoned it was often better to be sporty than to be swotty. I was always popular with the other kids and I think the teachers liked me as well, even if they knew that I was never going to be a contender for University Challenge. Like most kids, I got into a fair few playground scrapes and occasionally the heidie had to tear a strip off me. That didn’t go down well with my mum, especially if she was summoned to the head-master’s office. I have to say, though, these moments were few and far between because I got away with a hell of a lot.

From the moment the bell sounded in the morning, I longed for the ring that signalled the school day was over and the fun could begin. My brothers were also into football from an early age. It was all we knew. If you didn’t play football, you got left behind in the kind of circles we had. And, of course, it was even better if you got to play with the big boys. That way you quickly learned how to roll with the punches and how to grow a thick skin. It was a case of sink or swim . . . and I learned very quickly the kinds of skills that were needed to save myself from drowning. I got roughed up pretty much every time I played. There was no holding back and I remember going home and my mum sighing because my trousers would be ripped at the knees, leaving her to look out the needle and thread.

But I was a bundle of energy and my mum always encouraged me to play football. Not once did I ever get a telling off for heading out with my pals to kick a ball. Even if it was pissing down we didn’t care; in fact, that was even better because you could come home caked in mud. What a laugh. This, to me, was my real education. It might not have been the three Rs as laid down in the school curriculum but it was the three Fs as laid down in the John Deans curriculum – football, fun and freedom. And not necessarily always in that order.

Academically, primary school was a right slog. There was no real pressure to get homework done because I think my mum knew how much I hated it so she never forced the issue. In any case, a lot of times I was at my granny’s and homework was rarely given a second notion after the first one had been ignored.

In those days, kids had to sit the dreaded 11-plus exams to decide what secondary school you would go to. Pass and you went to a grammar school with the clever kids; fail and you were turfed into the local comprehensive along with the rest of the duds. When it came to my turn to sit the 11-plus, no one was taking any bets on the outcome. It was a no-brainer, if you’ll pardon the pun. But even though I was on the lower rung of the academic ladder, somehow I still had this gnawing feeling that there was so much more to come from me, that I was destined for a better purpose. I just didn’t have a clue what it would be – who the hell does at that age? The only thing I was good at was football. This wasn’t just a case of a boy from the tough side of the tracks dreaming his life away. But all I knew was that staring at the four walls of a classroom, listening to someone droning on about Shakespeare or Pythagoras was not my idea of how to spend your day. By my early teens, I lived for the joy of playing football. The minute my eyes popped open every morning, I was already running up and down the pitch, the ball at my feet and the wind in my face. Perhaps the notion of becoming a footballer – a real footballer, not like in the comics – was slowly forming in my head. You didn’t need academic qualifications to score a goal, all you needed was a determination to be good at football. And the more I thought about it, the more the dream became a possibility. My mum was my greatest fan. She did everything she could to encourage my football and she kept telling friends and neighbours: ‘Wait till my John turns professional.’

Real life, though, was different. Inevitably, I blew the 11-plus and was sent to Johnstone High, less than a mile down the road. It was a new chapter but a familiar story. Lessons at the high school were naturally even tougher, even though they were supposed to be tailored to your own level of ability. The bottom line, though, is I just didn’t give a toss. I’m sure if I had put in more effort I could have left with something. But, perhaps with no father figure pushing me on, I just wasn’t up to the grade, any grade. I began to dread going in some days. The only thing I looked forward to was the sports day.

Secondary education was still an eye-opener, however. For one thing, some of the teachers were real hard bastards. These guys, dressed in their black gowns, didn’t take any shit. I think they reckoned teaching in a comprehensive was somehow their punishment for being bad at their job . . . so they took their frustration out on the pupils. I was always getting into bother. They were all on second-name terms with me. ‘Deans, come here’, or ‘Deans, report to my office after school’ were familiar cries. I used to just laugh it off, but there were some teachers you didn’t mess with.

There was a guy in woodwork called Telford and you crossed him at your peril. He belted me across the hands a few times with the tawse, a long leather beast of a thing, and I don’t mind admitting he had me in tears a good few times. Of course, you always tried to be the big man and not let the other kids see you greetin’. Losing face in the playground would sting more than the belt.

Some days I just didn’t bother going in. I dogged it and my mother would get visits from the school board truant officer to find out why young John wasn’t at school. My mum was an honest woman and she didn’t like the fact that I was skipping classes or, worse, telling her lies. She wasn’t a soft touch, although she knew I was a bit of a rascal. So when I stepped over the fair play mark, she was waiting for me with a carpet beater. Everyone in the village knew her so there were eyes and ears everywhere to make sure you toed the line. Woe betide you if one of the neighbours reported back that young Deans was out of order for any reason. Mind you, the neighbours weren’t slow to give you a clip either.

With no proper income, my mum sometimes worked in local fields picking strawberries to earn a few bob – actually the equivalent now of 50p a day – when they came into season and occasionally she turned a blind eye to the truant officer and let me go with her. I was very close to her. I knew life was hard. And she had also developed this phlegmish cough and seemed to be sick often. Some days she found it hard to catch her breath. But I was too young to notice anything seriously wrong, even though the tell-tale signs of TB were staring us all in the face. Sometimes we’re too busy living to worry about tomorrow but the shadow of TB refused to go away. In time, I would curse it for the rest of my life.

Chapter Two

Growing Pains

By my early teens, I had already joined a couple of teams. There was always a lot of local rivalry attached to boys’ football teams, most of it down to territory but some of it down to religion. You were either a Tim or a Proddy. There was nothing in between. My father was a Protestant and my mother was Catholic but I can say, hand on heart, that religion was never an issue in our house. We weren’t ones for going to church or chapel but when it came to school, I went to the Protestant one.

Don’t ask my why because I don’t know. It’s just the way it was. Perhaps because it was closer to the house, I don’t know.

I’ve always hated sectarianism on any level. Growing up in the west of Scotland, you can’t avoid it, even more so when you play for either of the Old Firm. But almost every Celtic or Rangers player I ever knew wanted nothing to do with it. Sure, they understood the clubs’ old traditions, but that was it.

The first time I realised religion was a problem came after I started playing for Johnstone Thistle in Johnstone. It just so happened they were known as a Protestant team but that meant naff all to me. All that mattered to me was I was playing for a half-decent team and getting a regular game. And I was also playing for Johnstone St Margaret’s, a juvenile team which was a largely mixed outfit but mainly Catholic. Between these two teams, I was cramming in a lot of games and making a reasonable name for myself. A neighbour who lived across the road from us, Charlie Scarf, ran Linwood St Conval’s, a local amateur team that was based two minutes’ walk from where I lived. The Convies were the top local amateur team. They had some really good players in their ranks including Jim Orr, who later played for Celtic. Charlie had heard good reports of me playing for Thistle and asked me if I fancied playing for St Conval’s. Well, I knew they were a good team and I just saw it as a chance to maybe play in a better team and become a better player. So I said yes, not realising the little local storm I had triggered. Word soon got out that young Deans had signed for ‘the Catholic team’. Unknown to me, I was the first Protestant to sign for the Convies. And it didn’t go down well with the other side. Let’s be clear here, this wasn’t exactly a Mo Johnston–Graeme Souness moment and, looking back, I still can’t understand how easily tempers got frayed over a teenage boy playing football for a team from another religion. Still, I began to get the evil eye from some people I had always thought to be friends. There were a lot of snide comments. Community spirit often goes out the window when it comes to religion. I’m sure my ma must have heard the whispers that I was ‘kicking with the wrong foot’. Right away, I knew this wasn’t worth the aggro, even though I was disappointed. So I went to Charlie and told him I couldn’t play for his team. He understood right away, tore up the contract and I went back to playing for Johnstone Thistle and St Margaret’s.

I also played for the 1st Linwood Company of the Boys’ Brigade. My mum thought the BB would enforce a sense of discipline in me and I suppose it did to an extent. Although I was a bit of a rascal, I never spoke out of turn to neighbours because I knew I’d get a clip round the ear. I was brought up to respect my elders. It was just teachers I didn’t like.

The church was at the heart of our community. We occasionally went to the local Church of Scotland even though my mother was Catholic. Again, growing up I never questioned this because I had no reason to. The BB was good for me because I slowly realised that everybody needs a bit of discipline in life to achieve their goals and by now I had my heart set on being a professional footballer. Football was dominating my whole life. At weekends, I played for the school team in the morning and the BB team in the afternoon. The school team didn’t even have a proper kit. I used to come home with my strip filthy and my ma would wash it and dry it in front of the coal fire so I could wear it again when I played for the BB in the afternoon. At other times, she would use a handwringer to try to get the shirts and socks dry. She never complained because she could see how much football meant to me.

Playing so much meant I was a pretty fit kid. I ran everywhere, I was Mr Perpetual Motion. I couldn’t sit still, perhaps that’s another reason why I didn’t like school, because I felt constrained somehow. I was bursting with energy and needed a big release.

Growing up in the shadow of Paisley, it felt natural to be a St Mirren supporter. They were the local team and a pretty good one at that. Sure, it would have been easy to grow up supporting Celtic or Rangers, especially because success was guaranteed even then, but I chose to back my local heroes, not least because Glasgow seemed a million miles away. St Mirren was where my loyalties lay. You cared about them. They may not have been a top team but they were my team and that was all that mattered.

I dreamt of one day actually donning the black and white stripes and playing at Love Street. For me, this would have been top of the world ma, top of the world. Believe me, it’s good to dream, especially when your aspirations might one day carry you on a magic carpet ride and over the rainbow.

My mum had no worries about letting me get the bus to Love Street with a pal – these were certainly more innocent days when parents could let their kids have their independence without worrying what kind of people were trawling the streets. We would stand outside the same turnstile at one o’clock every Saturday we didn’t have an afternoon game, hoping someone would give us a lift over. And someone always did. Back then, football really was the working man’s game and the people of Paisley and the surrounding towns were distinctly working class and proud of their humble roots. St Mirren drew good crowds to Love Street, not the numbers that frequently flocked to Ibrox or Parkhead but still a respectable attendance.

My memory of the first match I ever saw at Love Street has, I’m afraid, vanished in the mists of time but I do remember seeing some big games there, including both halves of the Old Firm. It’s funny because all my memories are in black and white, like old monochrome TV pictures. I was happy to be a Buddie, the nickname that all St Mirren fans are known as. Me and my pal had a favourite spot behind the goal that St Mirren were attacking and then at half-time we would switch ends so we could get a great view of a St Mirren goal. The terraces always seemed to be permanently shrouded in tobacco smoke because virtually everyone smoked in those days. Most men had also been to the pub before the game, so you could smell stale beer from the guys standing next to you.

The moment that is most enshrined in my mind is when the Buddies won the Scottish Cup in 1959. I wasn’t yet a teenager the year St Mirren swept aside Aberdeen 3-1 in the people’s final at Hampden before a crowd of 100,000 – the last time the national stadium played host to a six-figure crowd for a final that didn’t involve the Old Firm. To this day, I can still reel off the names of that team – Walker, Lapsley, Wilson, Neilson, McGuigan, Leishman, Rodger, Bryceland, Baker, Gemmell and Miller. I just remember the waves of excitement that built up mainly in Paisley but, of course, the thrill of the whole occasion was also felt in neighbouring towns like Linwood, Elderslie and Johnstone. I was too young to go all the way to Glasgow to see them, but my ma let me join the thousands who packed the streets of Paisley as the team toured the streets in an open-top bus that night.

I positioned myself at Paisley Cross and it was fantastic just to be there. I’d never seen a cup so big. Being slightly on the small side of tinchy, I had to force my way to the front of the crowds just to get a glimpse otherwise it would have been difficult to see anything. But I didn’t care; just to be there and joining in the celebrations was enough. It might not have been dancing in the streets of Raith but grown men were jigging with joy all over the place. Happy days and ones that naturally set a hare running in my mind. Being a professional footballer seemed so glamorous even in the dog-eared days of the late fifties and early sixties. All that adulation, the glory and the beautiful game was a heady elixir for any boy who dared to dream the dream.

Everyone has a favourite player when they’re growing up and my hero was Saints’ swashbuckling striker Gerry Baker, a no-nonsense centre-forward loved by the fans for giving 110 per cent every game. It would be wrong to say he was a role model for me but he definitely left a huge impression. Gerry was actually born in America but moved to Scotland as a child and was brought up in Motherwell. He played for his home-town team before moving to Love Street in that fantastic cup-winning season. And he became a Love Street legend by netting one of the goals that sunk Aberdeen in the final. Gerry had a great work ethic and a fantastic rapport with the fans.

Years later, I became good friends with Joe Baker, the former Hibs striker who was the first Scot to transfer to an Italian side when he moved to Torino in 1961. We met on the pro-am golf circuit and struck up a good rapport.

One day he casually mentioned his older brother Gerry had played for St Mirren and I had no idea it was the same player I used to worship from the old, gnarled terraces at Love Street. Talk about a quirk of fate. Joe was fairly tickled when I told him about how much I admired his brother and he promised me that the next time Gerry was up visiting him in Wishaw from his home down south, he’d give me a call and we could all meet up and have a few drinks and talk about good times gone by. I couldn’t wait. No matter how many famous people you meet, the chance to shake the hand of your boyhood hero can still send a tingle through you.

Sadly, I did get to meet Gerry, but only under the most unfortunate circumstances. A couple of weeks after that conversation, Joe dropped dead from a heart attack at the age of 63. I was with him when he collapsed at Lanark golf course during a charity event in 2003. I was devastated to lose a true friend and I still miss Joe. Gerry, naturally, was one of the pallbearers, but it was terrible to finally shake his hand at his own brother’s funeral. Joe was a great guy and so was Gerry but it’s not the best way to finally meet one of your childhood heroes.

By the time I was 14 my mind was made up that I wanted to be a professional footballer. Every spare moment I had was spent kicking a ball and my body had taken on a slightly stocky outline. I wasn’t the tallest guy on the pitch but, as they say, size didn’t matter and no one pushed me around. I could dish out the rough stuff when I had to. I had added good muscle tone to my legs and I felt that I could run all day. I had a ‘good engine’, that phrase so loved by all the pundits. I also discovered I had a talent for heading the ball, despite my size. I liked nothing better than to challenge the bigger kids at high balls. You should have seen their faces when this slip of a lad – at least in their eyes – often got up higher than they did. I thought it was a hoot. Gradually, I realised that somehow I could hang in the air for what seemed like a few precious seconds, almost as if I was being held up by some invisible force. And this helped give me that edge on boys who were a good few inches taller than me. Don’t ask me where this ability came from – I haven’t a clue. All I know is it became virtually a trademark talent for me that lasted throughout my career. And ultimately, it was this God-given talent to out-jump giant centre-halves that I reckon earned me my move to Celtic. Jock Stein always said he took me on because I could beat Big Billy McNeill in the air. Cesar and I have had a few laughs about that over the years and Billy still thinks it’s rubbish.

Strangely enough, I played mainly at centre-half for the school team. There was no rhyme or reason as to why I played there except for the fact that I was good in the air and powerful for my age. I would have played anywhere just to get a game but that was my adopted position.

Then I remember one game where the boy up front kept blowing chance after chance. I must have been pretty pissed off because at half-time I went eyeball-to-eyeball with the teacher and demanded I get a shot at centre-forward. Sounds a bit cocky, I know, but my ma had always drilled it into us all that if you don’t ask you don’t get. So for the second half, I was punted upfield and I scored. Then I scored again – and again. And from that point, I never looked back, certainly not at centre-half. I was a striker first and foremost. I was well chuffed. Let’s face it, the guys who grab all the goals get all the glory. Now I really could close my eyes and imagine I was Gerry Baker bearing down on an opponent’s goal, hammering the ball into the net before turning to salute the crowds at Love Street. Any dream will do.

Centre-forward also became my position for St Margaret’s and I soon earned a good reputation locally as someone who was a prolific scorer. Goals win football matches so I became something of a sought-after commodity. Scouts from the Juniors would regularly turn up at our games, but not just to see me. Linwood and the areas round about like Johnstone, Elderslie and, of course, Paisley, were hotbeds of good, strong football talent. A lot of the guys I played with were good enough to make the grade professionally, and many of them did. But I was happy playing Juvenile for St Margaret’s, even though I kept holding out hope that one day opportunity would come knocking with the chance to impress someone from St Mirren.

Dreams alone, however, would not keep me going from the time I left school and that day arrived almost too quickly and not a day too soon. I left at 15 armed with few qualifications to get me by in an ever-changing world, one that was, by the early sixties, changing at a rapid rate of knots. And I had to find my sea legs fast.

Daunting it may have seemed for most kids in my position, but I was determined to embrace whatever challenges came my way and I refused to sit back and wait for something to happen. I felt, having left the classroom way behind, I was now a man in a man’s world. My first job was labouring in a sawmill in Linwood. I was a general dogsbody but I didn’t mind. For the first time in my life I was earning my own money. It probably didn’t add up to a hill of beans in the grand scheme of things but all that mattered to me was I could feel real cash jingling in my pocket for the first time. I always made sure I gave my ma money for my keep. That was always part of the deal. She had remained my biggest supporter as I clung on to the dream of being a pro footballer. And it wasn’t just me. My older brother James played Juvenile to a good standard and I think would have had a good chance of making it had it not been for TB. My younger brother Robert was also good enough to play at a decent amateur level. So football really did seem to be in our family blood.

Mum came along to almost every match I played. I can still see her standing on the touchline, cheering me on. She often had to step into my dad’s shoes. She was a fantastic woman who never complained about her lot in life. My uncles on my dad’s side were also staunch supporters of me and my brothers. I don’t know if they ever thought any of us had a shot at glory but they were always right behind us.

I loved the idea of feeling like a grown-up. Even though I was a wee man in size, I wasn’t slow to develop some big man habits. Everyone smoked in those days, often from a young age, and I was no different. I actually have a hazy memory of picking up a dout from one of my uncles when I was about six and sticking it in my mouth. I know it sounds horrible and if I saw one of my grandkids doing that I’d scream blue murder. But these were different times and smoking was often seen as a glamorous pastime, a rite of passage on the way to adulthood.

Everyone lit up from movie stars to sports stars, from royalty to those on the bottom end of the social scale. Peer pressure probably had a lot to do with me picking up the dreaded weed early. Shocking as it sounds, I probably got through easily 20 a day, sometimes maybe more. We had no idea then of the health complications or, if we did, we just ignored them. People often ask me, how could you have been a top-class footballer and smoke cigarettes? The truth is that I don’t think it made any difference to me. I trained hard and I made sure I was as fit as I could be. I was young and I was energetic. The fact that I liked the odd fag was neither here nor there. None of my managers ever asked me to stop, although Jock Stein made it pretty clear he thought it was disgusting. I suppose the other side of the coin is would I have played better if I hadn’t smoked? Would my body have been better equipped to cope in games where my energy was sapped and my legs were gone? Frankly, I don’t know. Doctors will always tell you it’s better not to smoke whether you’re a sportsman or not and that is undoubtedly right. All I can say, though, is I don’t think it affected me one bit.

I didn’t stay long at the mill and also worked at an engineering shop that built chassis for caravans . . . my job was to paint the chassis. Then an opportunity came up for a better-paid job at Stoddard’s carpet factory in Elderslie. Stoddard’s were big business in and around the Paisley area and a name known all over the country. It was a great place to work and, what’s more, they had a works football team and soon I was getting a regular game. It was full-on stuff with games against other local firms. No quarter was given or expected and I loved it. There were a couple of guys who had played either professionally or at Junior level and I think they spotted that I had a wee bit of potential. They were always dishing out tips when they weren’t dishing out tipped fags.

Quite a few of the loomers had a scam going on. On certain days they were flogging end cuts off cheaply. Right away, I fancied a piece of that. Anything to make a few bob extra and you could count me in. So, because I was the fastest kid on the Stoddard’s block, I used to have to run from one end of the factory to the other with the knocked-off pieces of carpet. And I’ll tell you, some of them were bloody heavy! It was a good half a mile because it was a huge factory. But I maybe earned about £1 or £1.50 a carpet depending on its size. But the extra money always went back into the house. I was already earning more than my ma was getting in benefits so the extra money was obviously handy. I had no problems with that. It just went into the family pot but I still had enough to keep me going. Once again, I felt I was mixing it with the big boys. I was still playing Juvenile for St Margaret’s but I felt the clock was ticking. I was always confident that I could crack it as a footballer. That wasn’t arrogance, just an inner belief that I could play at a high level. I think you need that kind of drive to succeed at anything. I was a kid in a hurry but I couldn’t shake off that feeling that unless something happened fast I could miss the boat. My ma never wavered, though, in her belief that ‘her John’ would one day be able to tell people he was a professional footballer. I could always hear the pride in her voice. I just needed the right break to get on to the next level.

Chapter Three

Dixie of the Farmers’ Boys

That break finally came when I was 17 and I got a trial with Neilston Victoria Juniors. Neilston were a pretty decent team who played in the old Ayrshire league. The goalkeeper, Sandy McIlwham, would go on to play for Queen’s Park in the old Scottish second division, Tam McMillan became a stalwart at Aberdeen and Jim Orr, my old Johnstone Thistle team-mate, would sign provisionally for Celtic. Neilston’s manager was a real character called Hammy Frew. He nearly always wore a hat and a checked overcoat. He looked like a mixture of Beau Brummell and an old-style movie actor, always immaculately turned out no matter where we were playing.

Hammy’s word was law and, even though he was on the smallish side, he could still intimidate guys who had played at all levels and thought they had seen and done it all. Hammy seemed to take an instant shine to me and soon I was invited to join Neilston permanently. To me it was a really big step on the road to wherever it was I was headed.

Things were going great. I had a good job, sticking two fingers up to those teachers who thought I would just fall by the wayside, was earning reasonable money for the time – about two quid a week – and could finally see my football ambitions moving in the right direction.

The only dark cloud on the horizon was so much closer to home, creeping up on me like some kind of shadow. My mum had been in and out of hospital a good few times with TB. She wasn’t the only one to come down with it – both my brothers and my sister suffered the endless coughing and wheezing. I was the only one untouched by its ravaging consequences.

I was worried about my mum. She had always seemed such a strong woman, the anchor in the face of life’s storms. I owed her everything, but the shadow of TB wouldn’t go away. I don’t remember talking about it to my brothers or sisters but all of us must have had private fears, especially in light of my dad’s early death. But my mum always rallied after a spell in hospital and life would go on pretty much as before.

She was so pleased about me playing for Neilston. Not only was it our local Junior team, or as near as dammit, but she knew right away it meant progress. It was obviously a bigger stage than playing Juvenile every Saturday. We regularly attracted healthy four-figure crowds.

It was around this time that I first started to be called Dixie. Don’t ask me who it was that first coined the name for me. I reckon it must have been one of the older guys because, frankly, the name Dixie as in Dean – not Deans – meant hee haw to me. I just reckoned it was a nice nickname because of the double D. It just rolled off the tongue, like Jinky Johnstone, for example. And it just seemed to stick. It wasn’t until a good bit later that one of the older players at Neilston put me right over the origins of Dixie. It was, of course, the nickname given to the legendary Everton striker of the 1930s, William Ralph Dean. Frankly, I’d never heard of him but after checking him out, I felt pretty chuffed about being called Dixie. Dean was one of the most prolific goalscorers of his generation and a legend on Merseyside. He was incredible. He bagged 349 goals in 399 games for the Toffees in 12 years, between 1925 and 1937. Pretty good going by anyone’s standards, no matter when you played. So if you’re going to copy a famous football nickname, it might as well be this one. There’s only one Dixie Dean, of course. In the same way, I suppose, there’s only one Dixie Deans. Anyway, I felt the nickname was suddenly a badge of honour. And it undoubtedly helped people remember who you were.

Amazingly, over the years, some people actually have thought I’m the Dixie who played for Everton. One guy at a football function, a well known TV racing pundit, actually came up, shook my hand and said his dad had been a great fan. He went on and on about how many times his dad had seen me play. He just said: ‘Christ, it’s an honour to meet you, Dixie.’

He carried on with this huge spiel and kept on mentioning Goodison Park. My jaw slowly dropped as I realised he thought he was chewing the fat with Dixie Dean of Everton and not Dixie Deans of Celtic. He even said I looked in great nick. The fact that I spoke with a thick Scottish brogue and not a trace of a Scouse accent didn’t seem to put him off. Nor did the fact that for me to be Dixie Dean I would have been about 90. I must look like I had a hard paper round. I might not have been in the first flush of youth but I wasn’t exactly a scone of yesterday’s baking either. You had to laugh. Even some of the punters in my pubs over the years got mixed up. They said things like, ‘I never realised you played for Everton’, and you just go along with it rather than go through the whole thing again. Other times, it could get you out of embarrassing situations with the boys in blue . . . and I’m not talking Rangers. If the cops pulled you over, it was easier to use your celebrity name to get off with any traffic misdemeanour. It’s funny, really, because the internet has made it even more confusing with the names bracketed together. But I’m not complaining. I reckon the name Dixie was good for both of us.