9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

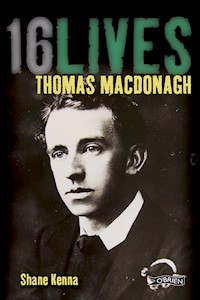

Born in Cloughjordan in Co. Tipperary, MacDonagh was a poet and playwright, an educator and political activist. Appointed to the IRB Military Council he became a member of the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic and was a signatory of the 1916 Easter proclamation. During the Rising MacDonagh was commandant of the 2nd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers and occupied the Jacobs Biscuit factory garrison. Following an inspiring speech at his Court Marshal he was executed on 3 May 1916 at Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin. In this meticulously researched biography Shane Kenna places this remarkable man within the great pantheon of Irish Republican heroes. He provides a riveting reconstruction of the life of a man whose death played such a key part in the shaping of modern Ireland. 'an epic new series of books' - RTE Guide on 16Lives

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

The 16LIVES Series

JAMES CONNOLLYLorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLINBrian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETTHonor O Brolchain

EDWARD DALYHelen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTONJohn Gibney

ROGER CASEMENTAngus Mitchell

SEÁN MACDIARMADABrian Feeney

THOMAS CLARKEHelen Litton

ÉAMONN CEANNTMary Gallagher

THOMAS MACDONAGHShane Kenna

WILLIE PEARSERoisín Ní Ghairbhí

CON COLBERTJohn O’Callaghan

JOHN MACBRIDEDonal Fallon

MICHAEL O’HANRAHANConor Kostick

THOMAS KENTMeda Ryan

PATRICK PEARSERuán O’Donnell

Acknowledgements

To write a biography about one of the signatories to the Easter Proclamation is truly an honour, and there are a number of people I would like to thank for their help and advice. Firstly, I would like to thank Lorcan Collins and Ruán O’Donnell for all the support they have given me in writing this book. Their knowledge and sense of history and heritage has been of great encouragement. I would like to thank Lorcan in particular for his friendship and support throughout the years. I am exceeding grateful to The O’Brien Press for giving me the opportunity to write this biography and for their courtesy and professionalism; particular thanks must be extended to Nicola Reddy, Helen Carr and Jonathan Rossney.

I would like to thank Pat Cooke of University College, Dublin for his exceptional knowledge of Thomas MacDonagh and the period from 1913 to 1921; Fr Sean Farragher of Blackrock College for his information about MacDonagh’s early years; Caroline Mullan, archivist at Blackrock College; John Kirwan, the archivist of St Kieran’s College, Kilkenny; Dr Brian Kirby of the Capuchin Archives; Tommy Doyle, senior archivist at RTÉ; the staff of the National Library Manuscripts Department and the National Archives, London; and Brian Crowley of the Pearse Museum for sharing his wealth of knowledge regarding Scoil Éanna. In the course of my research I had the honour of meeting Loretta Clarke, an inspirational person who greatly aided my work by facilitating a visit to the Jackie Clarke Museum. Particular thanks are also extended to Keith Murphy and the staff at the National Photographic Archive and those who work at the Military Archive in Dublin.

I would like to thank all my friends and family for their unwavering support, especially my mother, Olive, and Edel Quinn. I would like to also thank John Kenna, Gerard Shannon, Paul O’Brien, Aiden Lambert, Lucille Redmond, Muriel McAuley, Barry Kennerk, May Casey, Jim Casey, Anne-Marie McInerney, James Langton and Eamon Murphy (a fountain of knowledge regarding the Easter Rising and the Irish Volunteers!) for their kind support, words of advice and exemplary service.

This book has been written using all available sources related to the life of Thomas MacDonagh, and in the course of my research I have met countless people, so I can only apologise to those whom I have inadvertently forgotten to mention. Each and every one of you has been a great help, and your assistance is greatly appreciated. I hope this book will serve as a fitting testimony to all of the help you have provided.

16LIVESTimeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners.

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September.Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07.Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville (O’Connell) Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelors Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eóin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joins the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm.The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm.The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork Harbour.

22 April, 9.30am.The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt’s Rock.

10pm. Eóin MacNeill as chief-of-staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am, Easter Sunday. The Military Council meets to discuss the situation, considering MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of The Proclamation of the Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVESMap

16LIVES- Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES, conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell,

16 Lives Series Editors

Contents

Introduction

His songs were a little phrase

Of eternal song,

Drowned in the harping of lays

More loud and long.

His deed was a single word,

Called out alone

In the night when no echo stirred

To laughter or moan.

But his songs new souls shall thrill,

The loud harps dumb,

And his deed the echoes fill

When the dawn is come.

(Thomas MacDonagh, ‘On a Poet Patriot’)

The last man to be invited onto the Military Council of the IRB, the body entrusted with planning the Easter Rising, Thomas MacDonagh was by all accounts a warm-hearted, humorous and talkative individual. Originally from Cloughjordan in County Tipperary, he had been brought up in a house full of music, story and prayer. His parents were teachers and his mother a convert to Catholicism, who enshrined in her children a belief in acts of individual charity and morality that would considerably influence his character. During his life he was a schoolmaster, a poet, a theatre manager, an astute literary critic, a supporter of women’s rights and the Gaelic League, and a friend to some of the best-known and influential artistic and political figures in literary Dublin. He sought fairer pay and better working conditions for secondary school teachers through the foundation of the ASTI, while his involvement with the Dublin Industrial Peace Committee in 1913 was underlined by a recognisable desire to seek a fair resolution to the Lockout. MacDonagh was sympathetic to the ambitions of the ITGWU, and while not a member of the union and far removed from the realities of its socialist policies, he greatly favoured the workers rather than the employers arising from a sense of justice, fairness and a natural support for the underdog. Finally, he joined the Irish Volunteers out of a sense that nationalist Ireland needed to defend Home Rule. If he had not become involved with the Volunteers and then the IRB, which ultimately led to his execution in May 1916, he could have lived out his life as a well-respected academic. Of particular interest is his final work, Literature in Ireland, a detailed study of the development of language in Ireland that, in a remarkable break from the thinking of many Irish nationalists at the time, rejected the assumption that a truly national literature could only be created within the Irish language. His friend Padraic Colum wrote of MacDonagh as:

A poet bent toward abstraction, a scholar with leaning towards philology – these were the aspects Thomas MacDonagh showed when he expressed himself in letters. But what was fundamental in him rarely went into what he wrote. That fundamental thing was an eager search for something that would have his whole devotion.1

This book seeks to examine MacDonagh’s place within the Rising and to portray a man who for too long was overlooked in favour of more celebrated figures. In part, it is because his role in the rebellion was a minor one, but it is also because there are no great symbolic tales attached to his name: he did not read the Proclamation to the Irish people from the GPO; his garrison at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory saw little action during the Rising; he did not die strapped to a chair or after marrying his sweetheart in a midnight ceremony; and the famed address he gave during his court-martial is almost certainly an invention. However, his life forms an interesting story of religious fervour, self-doubt, political activity, romance, joy and bitter sadness. His execution in Kilmainham Gaol is punctuated by tragedy: hours before his death, his desire to see his wife Muriel was thwarted, and from his final letter it is apparent that he was ultimately a husband and father concerned for the welfare of his family.

As a leading writer and critic, MacDonagh’s work, like that of Pearse, Plunkett and Connolly, provided a means through which the 1916 rebellion could not only be justified but also speak to future generations. However, his works have not been examined as thoroughly as those of his contemporaries: he did not write as prolifically about sacrifice as Pearse and Plunkett, while unlike Connolly he did not leave behind him a defined social policy. Some of his poetry casts the rebel dead of Ireland in a decided romantic light, but this does not equate with an enthusiasm for the blood sacrifice spoken of by his peers. Indeed, Padraic Colum recalled that MacDonagh would have accepted ‘reasonable settlement of Irish political conditions from the government of Great Britain.’2 Lamenting MacDonagh at the time of his death, Colum commented how:

His country was always in his mind but it did not fill it exclusively, as it might be said to have filled Pearse’s mind … I often had a vision of my friend in a Home Rule parliament, working at social and legislative problems and perhaps training himself to become Minister for Education.3

His eventual involvement in the Rising seems to have come about as a result of factors beyond his control, in that he became caught up in the excitement surrounding the Irish Volunteers, then in the increasing militarisation of society that followed the outbreak of World War One, and finally in his co-option onto the Military Council of the IRB. The sequence of events that led to him becoming commandant of Jacob’s Biscuit Factory was more progressional than premeditated; ten years previously, no one could have predicted that Mr MacDonagh, the well-liked secondary school teacher and part-time poet, would have ended up before a firing squad after being convicted of treason. It is evident, however, that during the Easter Rising and his subsequent court-martial MacDonagh knew he was going to be executed and that he would never see his family again. But, unlike Pearse, he did not fixate on death or indicate that his execution had the power to change the course of Irish history. MacDonagh, in his last words, defined his life in Shakespearian terms, stating, ‘in all of my acts – all the acts for which I have been arraigned – I have been actuated by one motive only, the love of my country.’4 After his execution, The New York Times romantically lamented how he had ‘gone into battle with a revolver in one hand and a copy of Sophocles in the other.’5

Despite the fact that the Easter Rising for which MacDonagh was shot belongs to a former century, it still continues to affect the course of Irish life. Reflecting upon the effect of the executions of sixteen men in 1916, using the opportunity of the 97th anniversary of the rebellion, Irish President Michael D Higgins commented how ‘the removal of such a strong intellectual core from the definition of independence was the price we paid, a high one, because the succeeding twenties and thirties into the forties are very conservative and very different from either the life-witness or the writings of the people who were the direct participants in the Rising.’6 This is no more apparent than within the life of Thomas MacDonagh.

Notes

1 Colum, Padraic, Poems of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood (Boston, 1916), p. xxviii.

2 Ibid, p. xxvi.

3 Ibid, p. xxvii.

4 The last statement of Thomas MacDonagh, written in Kilmainham Gaol, 2-3 May 1916, in MacLochlainn, Piaras F, Last Words: Letters & Statements of the Leaders Executed After The Rising At Easter 1916 (Dublin, 1990), p. 60.

5The New York Times, 7 May 1916.

6 Patsy McGarry, ‘President reflects on 1916 Rising and its aftermath’, The Irish Times, 9 April 2012.

Chapter One

• • • • • •

1878 – 1901Beginnings

Thomas Stanislaus MacDonagh was born in Cloughjordan, County Tipperary, on 1 February 1878, the son of Joseph MacDonagh and Mary Parker MacDonagh. Joseph MacDonagh’s father was a small farmer and Fenian activist who lived at Kilglass on the Sligo-Roscommon border, and the family claimed to be descendants of the medieval Mac Donnchadha clan of Ballymote Castle, County Sligo. Joseph, born in 1834, was brought up on stories of how the family had defended Ballymote Castle against Sir Richard Bingham in 1586. After the death of his father while he was still young, it would have been expected that Joseph would take over the family farm, but instead he became the protégé of a priest uncle who taught him Latin, classics and a love of literature. Choosing to follow a career in education, Joseph attended the Marlborough Street School in Dublin, where he studied to be a primary teacher and was awarded a First classification from the National Board of Education. In 1867 he took work at Cloghan, County Offaly, where he met and married Mary Louise Parker. Unlike his father, Joseph MacDonagh was decidedly apolitical and wholeheartedly opposed Fenianism. Cynical about political activists, he recalled nationalists, particularly IRB men like his father, as ‘great cry and little wool, like the goats of Connacht.’1

Mary Louise Parker, born in 1843, was nine years Joseph’s junior and came from a relatively prosperous family. Her father was a Unitarian who had moved from England to Dublin when offered well-paid employment as a compositor in Greek for the Trinity College Dublin Press, and Mary Louise grew up in a house filled with music and literature, becoming an excellent pianist and a prolific writer of short stories and amateur poetry. At seventeen she took on teaching as a vocation and taught at Rush and other Dublin schools before taking work in Offaly. Developing an interest in Catholicism, Mary Louise decided to convert in anticipation of her marriage to Joseph.

With the zeal of the convert, Mary Louise was fervently religious and wholeheartedly embraced Roman Catholicism as a standard of living. In an article for The Catholic Truth Bulletin, she recommended regular prayer ‘for the relief of poor souls in purgatory,’ and joining sodalities (lay confraternities) to practice charitable works.2 Mary Louise believed, however, that pious Catholics needed to be practical about the number of sodalities they joined as this could only undermine their Christian duties. Like her husband, Mary Louise was not a nationalist and held that Ireland was an integral part of the United Kingdom. Moving to Cloughjordan in County Tipperary, a small town with a large Protestant community, the MacDonaghs became the first teachers in the town’s new Catholic school, established in 1877 on the initiative of Fr Denis Moloney, the local parish priest. The MacDonaghs were to manage the boys’ and girls’ school respectively. According to Roche Williams, an historian of Cloughjordan, the school was very cramped and underfunded, with large numbers of students crowded into small rooms.3 For this work Joseph received £44 while Mary Louise was reasonably in receipt of £32 (including fees). While these salaries were high by Victorian standards, teachers were only paid every quarter year, meaning that in reality the family were not financially secure.

As a strongly Catholic middle-class family, the MacDonaghs were initially put up in Fr Moloney’s home until they found more settled accommodation. By the late 19th century the Catholic Church was becoming increasingly influential as a new wave of devotional fervour swept Ireland and revitalised a faith which had long been moribund and suppressed. A new Catholic middle class was increasingly becoming apparent in Irish society, one which tended to adopt Britishness as the norm, into which the MacDonaghs fitted excellently. Unsurprisingly, the MacDonagh household would be one steeped in religious activity, and each evening the family would gather to recite the Rosary. Due to their hard work and sociable nature, they were soon admired throughout the small village, and Mary Louise became well known for giving piano lessons to local children after school. It was apparent that she adored the village, even writing poetry to celebrate it (something she had in common with her son Thomas). Her husband seems to have been known less for his educational abilities and more for his regular bouts of drinking and socialising about the town. All who knew Joseph MacDonagh regarded him as a warm and kind personality with a merry temperament, albeit one prone to overindulgence.

Joseph and Mary Louise had eight children, two of whom died in infancy. Thomas was their fourth. He was preceded by Mary Josephine and Eleanor Louise (sometimes referred to as Nell or Helen) and was followed by John, James and Joseph. Their home, under their mother’s influence, was filled with music and learning, and the children were encouraged to expand their knowledge in an idyllic rural environment. They enjoyed ‘running little manuscript magazines, playing paper and pencil games and reading improving books’4 under the tutelage of their parents. John developed a love of singing, while James was encouraged to play clarinet. Thomas, for his part, sang and played the piano. As a child he was ‘small, sturdily built, with curly brown hair and large grey eyes’,5 possessing a strong Tipperary accent, a fine sense of mischievous humour, and a love of ghost stories. His father taught him a love of the countryside, and he embraced the splendour of the rural Cloughjordan hinterland, climbing Scott’s Hill and wandering through Knocknacree Wood, which he later celebrated in a poem called ‘Knocknacree’:

The great wood lies beneath me in the sun!

Through all my days it has been still to me

As to the sailor lad the endless sea,

Or as her cloister to the happy nun;

And so must be until my race is run –

A place of natural childish piety,

Or haven to which I may safely flee

For restful quiet this loud world to shun.6

But as well as a love for literature, music and religion, Thomas’s mother also gave him a strong belief in personal morality and charity which would considerably influence his life. As a result, MacDonagh always held that wherever he saw distress or injustice, he was duty bound to intervene. This made him decidedly prone to the adoption of causes he saw to be just in his later life. In a later poem, ‘A Rule for Life’, one cannot but see the shadow of his religious mother:

Ne’er regret the evil that thou has not done;

E’er bemoan the good that thou has failed to do;

Manfully finish a good work once begun;

To thy God, to thy country and to thyself be true.7

Considering the emphasis on the arts and religion within the MacDonagh household, it came as no surprise that all bar two of the children chose artistic or religious professions in their later life. In 1895 Mary Josephine, the eldest daughter, became a nun with the Religious Sisters of Charity. Eleanor Louise married a policeman, Daniel Bingham, in 1897, and for a time lived in Cloughjordan and then in Clare before emigrating to the US. John had a remarkable operatic voice and trained to be a tenor singer in Italy. He was also an actor and writer, and in 1910 he wrote the script for the motion picture The Fugitive, directed by DW Griffith. During the Rising, John left a vivid account of the reality of Easter Week in Jacob’s Factory, and eventually became the director of the radio station 2RN, the first one in the independent Irish state. James briefly served in the British Army before joining the London Symphony Orchestra, where he played the cor anglais and oboe. One of his children, Terence, was a founding member of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and was awarded an OBE in 1979. Finally Thomas’ youngest brother, Joseph, like John, had hoped to fight in the Easter Rising, and had cycled from Thurles to Dublin to join his brothers at Jacob’s, but was unable get past British blockades. Following the rebellion he was elected Sinn Féin MP for Tipperary North in the 1918 general election. He was imprisoned during the election campaign and had previously been on hunger strike with Thomas Ashe in 1917, demanding political status for Republican prisoners. Rejecting the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921, Joseph was an active participant within the anti-Treaty IRA and while interned in Mountjoy developed peritonitis, dying on Christmas Day 1922.

However, despite their parents’ antipathy to nationalism, it is no surprise that three of the MacDonagh boys eventually became involved in the cause of Irish independence. The Ireland they grew up in was undergoing great social and political change. Since 1 January 1801, Ireland had been a constituent part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and governed directly by London through an administration operating out of Dublin Castle. Throughout MacDonagh’s childhood, the greatest challenge Dublin Castle faced was the question of the land, particularly along the impoverished western coast, where a large tenant farming class was dependent on landlords for their holdings. These farmers’ lives were incredibly insecure, as the tenancy system in Ireland was weighted in favour of the landlord, who could increase rent and evict tenants from their farms arbitrarily. In 1878 and 1879 a bad harvest, regarded as the worst on record since the great famine in the 1840s, caused enormous difficulties for farmers, which were further exacerbated by a fall in the price offered for Irish agricultural produce as the market favoured cheaper imports from America, Argentina and Australia. As a result, many farmers were unable to pay their rent and faced eviction, evidenced by the rise in evictions from 406 in 1877 to 1,098 the following year.8 To defend the rights of the tenant farming class, a Tenants’ Defence League was established in Mayo on 26 October 1878, and throughout rural communities across Ireland similar societies emerged. The following year saw the emergence of the Irish National Land League seeking fair rent, fixity of tenure and free sale beneficial to tenant farmers. The ultimate ambition of the movement was to establish peasant proprietorship on the land.

In Charles Stewart Parnell, the Land League had as president an articulate, educated Protestant landlord from County Wicklow who forcibly represented the Irish interest at Westminster. As a member (and later leader) of the Irish Parliamentary Party, he had been elected to the British parliament in 1875, and strongly supported the establishment of a devolved Irish parliament, a policy known as Home Rule. In later years MacDonagh viewed Parnell as a political hero. He described him as an ‘austere nationalist’9 and held him in deep regard as ‘a matter of fact politician’.10 His admiration for Parnell was such that he was outraged when a statue of Parnell that he considered gaudy was unveiled on Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) in Dublin.11 Parnell’s leadership of the Land League, while calculated to facilitate his rise within Irish politics, took place during what became known as the Land War between 1879 to 1882, a social conflict between landlords, supported by the government, and tenant farmers, organised through the Land League.

In February 1881, the British government introduced a policy of combining conciliation with coercion to deal with the land problem in Ireland. Under conciliation, the Liberal Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, introduced a Land Act on 7 April 1881, which established a Land Court to fix rents at fair prices and allowed for a commission to grant loans of 75 per cent of money needed by farmers to buy out their holdings. Tenants were also to be compensated if they improved their holdings. However, the Act came with a clause asserting that no tenant in arrears could avail of the Land Court and leaseholders were to be excluded until their lease was up for renewal. This meant that the poorer class of farmers, particularly those in the impoverished west, were excluded from its benefits. In effect, the Act was calculated to break the solidarity of the Land League by favouring wealthier farmers. The coercion policy was embodied in the Protection of Person and Property Act, which gave draconian powers to Dublin Castle. Chief Secretary William Forster announced that it would place ‘village ruffians and outrage mongers’ under lock and key.12 On 3 February 1881, Michael Davitt, the secretary of the Land League, was arrested, and on the same day, sensing that the government was moving against the Land League, its treasurer, Patrick Egan, made to France with league funds, outside of British jurisdiction.

On 2 March 1881 the coercion bill was passed. Dublin Castle spared little time in using its new powers, with some nine hundred members of the Land League arrested and interned in various prisons as Ireland increasingly descended into anarchy. At Cloughjordan, several Land League activists were arrested, including Michael O’Reilly, secretary of the Cloughjordan Land League, and James M Wall, a journalist with The Roscommon Herald. By 13 October 1881 Charles Stewart Parnell had been arrested and lodged in Kilmainham Gaol; within a week of his arrest, the senior Kilmainham prisoners issued a manifesto calling upon tenant farmers to withhold both their rent and the harvest. By 2 May 1882 Parnell had been released from Kilmainham with the understanding that he would use his influence to quell violence in Ireland. In return, the British government would facilitate the entry of tenants in arrears into the land court. This, it was speculated, would facilitate a new era of Irish and British co-operation, signalling an end to the Land War and eventually leading toward a Home Rule parliament. MacDonagh recalled later how the conclusion of the Land War had inspired the Irish nation to ‘struggle for legislative freedom and the certainty of triumph and responsibility.’13

Within four days of Parnell’s release, this new era of co-operation was stymied when a Fenian society calling themselves the Irish National Invincibles assassinated the new Irish Chief Secretary, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and his Undersecretary, Thomas Henry Burke, in Dublin’s Phoenix Park. A new round of coercion seemed inevitable and a bill introduced in the aftermath, known as the Crimes Bill, was even more draconian than what had gone before, allowing for special non-jury courts to try cases of treason and murder as well as giving summary powers of arrest and the power to ‘proclaim’ entire districts. The assassinations, coupled with the experience of coercion, effectively threw the Parnellite-Liberal alliance into disarray. Neither party would co-operate with each other until 1885, dramatically represented by the introduction of the first Home Rule Bill the following year, which provided for a devolved Irish parliament with limited legislative powers. The bill was defeated by 341 votes to 311, with significant numbers of the Prime Minister’s Liberal Party voting against their own bill. Despite this defeat, however, Home Rule was now firmly entrenched within the political agenda.

Even as a child, MacDonagh could not have been unaware of the tensions created by all these developments, especially when living in a rural area. But for most of his life, nationalism was to be dominated by constitutional rather than physical-force activism. More radical revolutionary groups, such as the Irish Republican Brotherhood in Ireland and Clan na Gael in the US, who together would plan the Easter Rising, were largely irrelevant and ignored. However, nationalism as a whole suffered a serious blow in 1889 when Parnell was exposed as the lover of a married woman, Katherine O’Shea. The fallout of this scandal was immense, forcing an acrimonious split in the Irish Parliamentary Party and dividing the country into pro- and anti-Parnell factions. Parnell died in 1891, and while the IPP bickered over his legacy, Home Rule became increasingly unlikely. Lamenting his great hero many years later, MacDonagh recalled: ‘Parnell exhorted us to national effort, not in terms of hunger and profit, but in terms of tradition and the sacred gift of the ideal for which we have stood against tramplings and settlements these thousand years: “keep the fires of the nation burning.”’14

In 1892 Joseph and Mary Louise decided that Thomas was to study in Rockwell College, a boarding school in Cashel, County Tipperary, founded in 1864 and administered by the Holy Ghost Fathers. The Holy Ghost Fathers were dedicated to the adoration of the Holy Spirit as well as missionary activity and work with the poor as part of a process of evangelisation. In Ireland they already administered several schools of national repute, including Blackrock and St Mary’s College, Dublin. While the reasons for sending Thomas to a boarding school, rather than educating him at Cloughjordan, are not entirely clear, Rockwell College had an excellent reputation; indeed, the Reverend Nicholas Brennan, President of Rockwell, explained to commissioners investigating intermediate education how ‘the boys who have passed [Rockwell] as a rule are equal to any of the boys passed through the other colleges.’15 The college also housed a Junior Scholasticate for the training of novice priests, and it can be speculated that by sending Thomas to Rockwell, Mary Louise was eager for her son to become a priest within the order.

The culture of Rockwell College was remarkably insular and conventional, with no nationalist ethos whatsoever. There was no attempt to teach the Irish language or Irish history. In terms of sport, the students played rugby and cricket, with MacDonagh, known to his peers as Tommy, eagerly embracing both. As a student he showed great potential in languages, particularly Latin and English, excelling as a student in letters and humanities. He was less gifted in mathematics, however, and showed a marked inability to grasp algebra.

In 1894 Joseph MacDonagh passed away, leaving his wife widowed with six children to care for. Thomas was only sixteen years old and, returning to his studies in Rockwell College, he decided to devote his life to missionary work and prepare for the priesthood. Writing to the Superior General of the Holy Ghost Fathers in Dublin, he requested entry to the Junior Scholasticate, stating:

I like its rules and customs and particularly the great object of all its members, and for which it has been founded. I first learnt of it from some of my friends, and now, having tried by every means in my power to find out to what life I have been called, I have concluded that I have a vocation for this congregation, and a decided taste for the missionary and the religious state. It has always been my wish to become a Priest and now that wish is stronger than ever, and it is to become, not only a Priest, but a missionary and religious.16

Accepted for the order, Thomas now moved from the main campus of Rockwell College to the grounds of the Junior Scholasticate, known as the Lake House. Having expressed an interest in missionary rather than diocesan work, MacDonagh was enrolled as what the order termed a surveilliant; that is, an adolescent boy who shows potential to go further within the Church. However, it was not a commitment to enter the priesthood, nor did it involve taking any vows. On completion, if they so chose, surveilliants could continue on to priesthood with the Holy Ghost Fathers. In Ireland the surveilliant was called a prefect, and life as a prefect at Rockwell was intense, vigorous and often lonely. Living at the Lake House, mass and private prayer were daily features in his life, as was intensive study regarding Church doctrine on issues of morality, liturgy and philosophy. Prefects were also regarded as part of the clerical administration, with duties in teaching, organising of games and activities in addition to management of the student dorms and study. In 1896 MacDonagh became a junior master, a role which included the instruction of junior students. He seemed to relish being a teacher, and one of his students recalled how he was appreciated by the boys in the class, as MacDonagh, who was quite short, appeared boyish, approachable, and friendly (he always seemed to be smiling, an impression given through a slight prominence in his teeth).17

It was around this time that he began to write poetry, and many of the poems written at Rockwell would be used in his first book, Through The Ivory Gate (self-published in 1902). It is clear from these and other sources that at some point during his time in Rockwell, his studies and the possibility of being called to the priesthood forced him into a crisis of faith. While evidence remains sparse as to why his vocation was challenged, some of the poems in Through The Ivory Gate hint at why he may have experienced doubt toward the Catholic Church and its teachings. Introducing the book, he describes his poetry as ‘a struggle of soul from the innocence of Childhood through disillusion, disappointment and ill doubt; and thence through prayer and hope and the pathos of old memories to lasting Trust and Faith.’18 In essence his first book of poems, if applied to Rockwell College, identifies MacDonagh as a young man struggling to come to terms with Catholic heterodoxy. At the heart of his crisis was an increasing preoccupation with death, as he strongly questioned the central tenet of Christian doctrine: resurrection and the afterlife. These doubts troubled MacDonagh greatly, as without any afterlife there was no hope. Almost mournfully he lamented:

Man comes and lives and goes,

Brief houred and frail as they –

And when he’s had his day,

Dies – for all time – who knows.19

Why he developed a preoccupation with death in Rockwell College has never been adequately explained; however, one biographer has cited that it may have been due to the death of a friend in the college.20 This supposition rests in the nature of ‘The Dream Tower’ section of Through The Ivory Gate, when, beginning in Poem Six, MacDonagh wrote about a colleague whom, while initially friendly, grew to be cold and distant. While MacDonagh never mentions his name, he appears to have died while at the Junior Scholasticate and the two were unable to reconcile. With MacDonagh overcome by guilt, he recalled his absent friend taking ‘my fairest treasure, my soul’s light,’21 and it was speculated that he wrote ‘De Mortuis’ in his memory, lamenting:

He is dead, my foe – I must be silent now,

Or speak at last whate’er I know of good

In him before whose cold set face I bow

In reverence humble. Once, when he had stood

Long hostile, he said, smilingly – ‘Forgive’

For years I have repented that I turned

In scorn away…22

His mood increasingly despondent, MacDonagh visited his friend’s grave at Rockwell, recollecting:

There is a green grave in Rockwell’s bowers,

Covered with fair and blooming flowers;

In that lowly grave thou liest –

Struck down, when thy hopes were highest,

Of a long and fruitful life,

Spent in holy strife.23

As a result of this crisis of conscience, MacDonagh realised that the religious life was something he was not prepared for, although, while rejecting much of the Church’s teachings, MacDonagh still retained enough religious belief to avoid the label of atheist. He finally decided he could not remain in Rockwell as a prefect and was not prepared for a vocation. This was an incredibly difficult decision for MacDonagh; through his mother in particular, he had been immersed in Catholicism since his childhood. On 22 June 1901 he wrote to the Order’s Superior General asking to be given permission to resign from the Holy Ghost Fathers. In a marked difference from the sixteen-year-old who had written in 1894 of his ‘decided taste for the missionary and the religious state’24, at age twenty-three he now wrote:

Having, after much hesitation and anxious questioning, come to the conclusion that I have no vocation for religious life, with sorrow, I request you to release me from the obligations contracted by me at my reception.25