7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

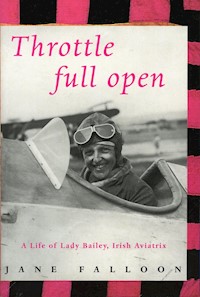

I have felt the need for a change of scene and interest lately.' -Lady Bailey on the eve of her London-Cape Town flight, March 1928. Mary Westenra, born in 1890, was the daughter of Derry Westenra, the fifth Baron Rossmore of Rossmore Castle, Co. Monaghan, a famous sportsman and rake. After a youth of much hunting, shooting and fishing, and little formal education, at the age of twenty she married Sir Abe Bailey, a South African tycoon of British extraction. Shuttling between England and South Africa with a much older man whose interests were very different from hers, and cut off from her beloved life of horses and hounds, Lady Bailey began to take flying lessons in secret. With astonishing rapidity, she became one of the world's most celebrated aviators, before setting out on the journey that would make her name: London to Cape Town and back. Flying in her De Havilland Moth, she was detained for several days in Cairo, where the authorities didn't want to let her continue without a man in the plane. Eventually she prevailed, and flew down the eastern flank of the African continent to Cape Town - and then turned back, en route for London up the western flank of the continent. Lady Bailey's riveting journal of this return flight has survived and is reproduced in its entirety here. Lacking a radio, she often lands in unknown places to ask directions, and recounts in unruffled prose her encounters with friendly Africans and unhelpful French colonials. Jane Falloon paints a rich picture of Lady Bailey's life, establishing her sporting pedigree and detailing the still-feudal environment of Monaghan in which the Lord's daughter grew up. The remarkable life of the businessman-imperialist Abe Bailey, who bankrolled his wife's adventures and always supported her despite a lack of warmth in the marriage, is also recounted. Lady Bailey herself emerges from this biography as one of the most remarkable Irishwomen of the century.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1999

Ähnliche

Throttle Full Open

A Life of Lady Bailey, Irish Aviatrix

Jane Falloon

To Mary’s second son, Jim Bailey CBE, DFC, MA, and his wife Barbara, without whose encouragement, practical help and enthusiasm this book would never have been written, and to Valerie and Thomas Pakenham, who introduced me to Jim and Barbara in the first place

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

List of Illustrations

1 Mary’s Background

2 Derry Rossmore and Richard Naylor

3 Derry and Mittie

4 Mary’s Childhood

5 Abe Bailey

6 An Unlikely Pair

7 Married Life, 1911–1926

8 Getting Away from Prams

9 The Flight from London to Cape Town

10 South from Khartoum

11 Interlude in South Africa

12 Mary’s Flight Journal, Pretoria to Gao

13 Mary’s Flight Journal, Gao to Stag Lane

14 Fame and Folly

15 After the Flying Was Over

16 Last Years

Appendix: Mary’s Paternal Ancestry

Acknowledgments

Map of Lady Bailey’s Flight Routes

Select Bibliography

Index

Plates

Copyright

List of Illustrations

p. 94Mary’s cartoon of her crash-landing at Tabora

p. 207Map of Mary’s flight routes

PLATES

1 Rossmore Castle Mittie Naylor as a young woman Derry Rossmore with children

2 Mary aged nineteen, with dogs

3 William, Richard and Mary Westenra Mary at the time of her presentation at court, 1909 Caricature of Derry by Mary

4 Shooting party at Elveden, Suffolk Photo in which Mittie’s face has been scratched out

5 Abe Bailey as a young man Cartoon of Abe Abe and Mary at Rossmore after their wedding

6 Fancy-dress party aboard R.M.S. Saxon Rust-en-Vrede, Cape Town

7 Mittie, Willie, Mary and Derry at Rossmore, 1913 Abe at Rust-en-Vrede, 1915 Cecil Bailey with Mary, 1915

8 Mary as a driver in the Royal Flying Corps, 1915 38 Bryanston Square Abe with the Prince of Wales, 1926

9 Mary after getting her pilot’s licence, 1927 Wearing turban after head injury At Brooklands

10 At Stag Lane before the flight to South Africa, 1928 Abe greeting Mary in Cape Town

11 At the Mount Nelson Hotel with Hertzog and Smuts Fogbound in Coquilhatville

12 Landing at Croydon at the end of the return flight, 1929 At Croydon with Mary Ellen, Noreen and Willie

13 Cartoon and poem about Mary from Punch On the Kharga Oasis expedition

14 With Amelia Earhart, Amy Johnson and Winifred Spooner, 1932 As a WAAF officer, 1941 Abe and Mary on their way to Buckingham Palace

15 Mary’s presentation at court, 1937 With nephew Paddy, 1938 With Ann and Noreen at Cape Town airport, c. 1948

16 At Rossmore with gamekeeper Paddy McGuinness At The Mains, Cape Town Abe and Mary’s burial place, above Rust-en-Vrede

1

Mary’s Background

Mary Westenra was born on the first of December 1890, in 30 Grosvenor Square, London, the house of her maternal grandfather. She was the first child of Derrick – always known as Derry – the fifth Baron Rossmore of Ireland, the fourth Baron Rossmore of England, and his wife, Mittie. Derry was the owner of an imposing castle on an extensive estate in Co. Monaghan, Ireland. It was sometimes known as Rossmore Park and sometimes as Rossmore Castle; in the town of Monaghan it was simply ‘the Castle’. Mittie came from the even more splendid Hooton Hall, in Cheshire, England. She was the daughter of Richard Christopher Naylor, a wealthy banker.

Both houses had been greatly enlarged and improved earlier in the nineteenth century. Rossmore Castle, built in 1827 in Tudor-Gothic style, had been made grander and more fantastical in 1858 by Derry’s father, who had added towers, turrets, balustrades and battlements, turning it into a fairy-tale Scottish Renaissance castle. Hooton had been transformed by Mary’s Naylor grandfather from a sober Georgian-fronted mansion into a structure of enormous size and splendour, with a vast sculpture gallery and an ornamented roofscape.

At the time of his daughter Mittie’s marriage to Derry, Richard Naylor was a man of considerable wealth. His family was connected with a small bank in Liverpool, Leyland and Bullen. He had inherited a substantial fortune from his mother’s brother, whose surname was Leyland. And he was involved in the cotton industry. In addition to Hooton Hall, he owned Kelmarsh Hall, in Northamptonshire, and Downshire House, in Belgrave Square, which is now the Spanish Embassy. At one time his London house was Hurlingham, in Fulham, now the Hurlingham Club. He was an enthusiastic sportsman and a successful owner of racehorses.

When Mary was born Derry was probably feeling at his most confident about his prospects and standing in the world. He was thirty-eight years old, married to the daughter of an extremely rich man who had bred only two daughters and no sons to inherit his wealth; he was the inheritor, through his older brother’s death, of an estate of nearly fifteen thousand acres, and of a most impressive house filled with superb furniture; he employed a great number of servants; he was a peer of both realms; and he was possessed of a cheerful and gregarious temperament. His wife Mittie, as well as being an heiress, was very handsome and a good horsewoman; she came from a most socially acceptable background and moved in the top circles of English society.

Mary was not born until Derry and Mittie had been married for eight years. Perhaps there were earlier miscarriages to account for this long delay, which would have made Mary’s arrival a source of particular relief and happiness to her parents. Ideally, of course, she should have been a boy, to guarantee an heir to her father’s title. But this small disappointment must have been quickly overshadowed by the happy realization that she was a healthy child and, as an added bonus, extremely pretty.

Although she was born in London, most of her childhood was spent in Ireland, at Rossmore Castle. On the first floor of the house there would have been a suite of rooms known as the nursery wing, consisting of a day-nursery, a night nursery, a bedroom for the nurse or nanny, and probably a little scullery. There would have been a full-time nurse or nanny, with complete charge of every aspect of Mary’s life, from her food and clothes to her health and manners and behaviour, as well as at least one, if not two, nursery maids to do the more mundane work of washing and ironing and bringing up the meals from the kitchens below. Mary would have been cocooned in this little world, seeing her mother when she was taken down to the drawing-room before her bedtime, dressed in her prettiest dress, expected to behave perfectly for that short time, for the amusement of her mother’s guests – a small performer, to be laughed at, but not petted or loved. Any warmth would come from Nanny upstairs, and perhaps if Nanny were a dour Scot, who didn’t approve of soft silly ways, there would be no hugs there either. Such a childhood might partly account for Mary’s distant relationship with her own children, who never felt their mother showed them adequate affection.

Rossmore Castle must have been frightening for a small child in the dark winter evenings, as the long passages, filled with portraits and sculpture, gradually turned into dark caverns of menacing presences and flickering shadows. When Mary was very tiny her nurse accompanied her down to the drawing-room after tea, but as she grew older she must often have ventured out on her own, and found her way down to the vast kitchens and sculleries and game larders, which, every year in the shooting season, were hung with pheasant and hares and woodcock shot by her father and his friends.

The drawing-room was enormous. It had been built by Mary’s great-grandfather, the second Lord Rossmore, when he finally came into his inheritance, in 1827. He had a neighbour, a Mr E.J. Shirley, who was building a huge house for himself called Lough Fea, a few miles from Rossmore. The two men – whether from animosity or fun – decided to compete with each other as to who could build the larger room. Lord Rossmore enlarged his drawing-room five times in order to be the victor, but was finally defeated when his building reached the edge of a cliff. Mr Shirley meanwhile had victoriously built on a great hall with a lofty hammerbeam roof, a minstrel’s gallery, and an arcade at first-floor level – larger by several yards than the Rossmore drawing-room. Mary’s niece Brigid Westenra remembers the huge room cluttered with fine furniture and with three beautiful glass chandeliers suspended from the ceiling. Peter Somerville-Large has described the room as it would have been in Mary’s childhood: ‘Photographs of the period show the great drawing-room cluttered with tables and chairs, crocheted antimacassars on fat sofas covered with chintz or linen, windows framed by heavy curtains and pelmets that looked as if they would pull down the house, ferns, palms, and perhaps a painting on an easel.’

Later, as Mary grew older, she would become familiar with the library – a lovely room, its walls lined with leather-bound books, overlooking the lawn. She ran up and down the enormous polished-wood main staircase. She must have been half terrified of all the gaunt figures, in coats of armour, standing menacingly in the hall against the dark oak panelling. She certainly grew to love the two nearly life-size bronze statues of Russian horses in the hall, with riders on their backs, and giant birds perched on their shoulders. When Mary was much older, she bought these statues in the sale of Rossmore furniture held by her brother William, the sixth Lord Rossmore, and had them shipped to her home in South Africa, where her grandchildren remember them standing guard outside her garden door.

There was so much else to discover and explore in the great house: stillrooms beside the kitchens, where jams and ciders were made; a vast laundry, with great vats for boiling linen, long wooden tables for folding the sheets, great tubs and washboards for scrubbing and an array of irons, heated by burning coals, of all shapes and sizes, a small army of laundry maids toiling away – and all this permanently shrouded in a haze of steam.

Each function of the house was performed by its own band of servants. It is doubtful if, as a child, Mary would have been allowed to spend much time in the kitchen, visiting the cook and the scullery maids. Children weren’t encouraged to spend too much time with servants. One of the fears was that they would start to speak with a brogue – very infectious, but not approved of, except as a jokey way of talking. An English voice was essential in an Anglo-Irish family of that time.

Relations between master and servant in Ireland at this time were often cheerfully informal, but this was only half the story. In some respects the Anglo-Irish attitude to servants was the same as that to dogs and horses: fond, when they were behaving and in their place, but harsh if they stepped out of line. The staff did not all live in the house. The 1901 Census lists only six staff in the house, but that figure is artificially low because Lord and Lady Rossmore and their family were away at the time, and their personal servants were away with them. In the 1911 Census there were seven living-in staff, and Derry and Mary were at home. By then Derry was far less well off. In the 1890s there were many more staff living on the estate – in the twenty cottages that existed then, and in the stable yard – who either worked outside or came up to the house each morning. People would also have been employed from the nearby town of Monaghan.

To work in the Castle was often a family affair. The gamekeeper’s sons would be employed about the estate – in the timber yard or the garden – and later one of them would take over from his father. A favourite family of Mary’s were the Mulligans. Micky Mulligan was the head gardener and Mary loved going to visit his family in their cottage on the estate. A few years before Mary’s birth, the cook married the head gamekeeper, and their son Paddy McGuinness in turn became the head gamekeeper. Paddy worked on the estate from the age of twelve, and retired sixty years later. His son Owen, now over eighty, also worked on the estate for much of his life. When asked what the people of Monaghan thought of the Rossmores, Owen replied, ‘I don’t know why they should not be liked. They were inoffensive people.’

Mary was treated as a little princess. She was the eldest child, forgiven for being a girl as soon as her little brothers arrived, living in a vast castle on an enormous estate, and in a feudal atmosphere that lasted in Ireland much longer than it did in all but the very grandest houses in England. The boundary of the Rossmore estate was near the town, and there would hardly have been an inhabitant of Monaghan who would not have known Mary, or taken an interest in her as she was growing up. This feudal atmosphere did several things for a child in Mary’s position. It gave her confidence in her standing in the world, and a strong sense of belonging: she was surrounded by her world and her people. It also gave her a certain arrogance. Mistakes would not be countenanced, respect would be of paramount importance, fools would not be suffered gladly. As she grew older Mary showed signs of all of these attitudes, but her most lasting characteristic was a strong affection for her roots – for her Irish home and her Irish background.

Curiously, if Mary thought of herself as having Irish blood in her veins, she would have been wrong. Her ancestry was part Scottish, part Dutch, part English. The Rossmores who married wives whose homes were in Ireland married Anglo-Irish women, not native Irish. The main reason for this was religion. Before Mary’s grandmother Julia converted to Roman Catholicism in 1879, no Rossmore was a Catholic, and none married anyone who was not a Protestant – except, curiously, Mary’s great grandfather Warner William Westenra, whose first wife, Marianne Walsh, was Catholic. The very fact of being born and living in Ireland made people think and talk of themselves as Irish, and have tremendous loyalty to the country, however foreign their roots. But although the Anglo-Irish were less inhibited and more gregarious than their counterparts across the Irish Sea, their customs, loyalties, education, tastes and manners were all influenced by their British origins. Louis MacNeice described the Anglo-Irish character as ‘Nothing but an insidious bonhomie, an obsolete bravado, a way with horses.’ Sean O’Faolain gave a more measured assessment, arguing that ‘culturally speaking the Anglo-Irish were to create modern Irish-thinking, English-speaking, English-writing Ireland. Politically, and in the largest sense socially, they were either wicked, indifferent, or sheer failures.’

The Westenra/Rossmore family had the typically Anglo-Irish love of sport, and their upbringing produced a healthy, courageous attitude to life. Mary’s family all had a remarkable degree of daring in their make-up. By the time Mary was six, or perhaps even younger, her father must have realized that she was going to be a good horsewoman. Children of her background started to ride when they were only three or four. Their first mount would be a donkey. Very soon a tiny pony would be found. Before long, they would be going out hunting on a leading rein. All this was probably the most important part of Mary’s young life. Her mother Mittie had been an intrepid horsewoman, but after a severe riding accident, soon after she married Derry, she gave up hunting. Mittie’s sister, always known as Doods or Doody, was a brilliant horsewoman, and continued to hunt into her eighties. She and Mary were very close, but it was Mary’s father who was her main mentor and guide.

2

Derry Rossmore and Richard Naylor

Derry Westenra, born in 1853, was the second of six children of Henry Robert, the third Lord Rossmore. His elder brother, Henry Cairnes, known as ‘Rosie’, became the fourth Lord at the age of nine, upon the death of their father. Rosie was sent to Eton, Derry to Rugby. Derry had no expectations: all was to be Rosie’s. When Derry was sixteen Rosie joined the prestigious regiment of Life Guards. Derry himself went into a less fashionable regiment, the Ninth Lancers, at nineteen.

Two years later, in 1874, everything changed. Rosie, riding in the Guards Cup Race at Winsdor Steeplechases, was mortally injured by a fall from his horse. The story is told that as he lay in agony he uttered a series of shocking curses – much to the dismay of Queen Victoria, who was in attendance. Three days later Rosie died.

Thus, at the age of twenty-one, totally unprepared, Derry became the fifth Lord Rossmore. Until then he had been enjoying life in a cheerfully feckless and irresponsible way, as recounted much later in his memoirs, ThingsICanTell. It is a silly book, but it is obviously the picture of himself that Derry wanted to leave to posterity, and it tells us much of what we know about him as a young man. His neighbour, Leonie Leslie, said it should have been called ThingsIShouldNotTell. Derry hoped to be seen as a devil-may-care buccaneer who took extraordinarily foolish risks, gambled, philandered, spent recklessly – and, when occasionally looking for excuses for this behaviour, blamed it all on the fact that he was ‘an Irishman’.

He wrote of himself at the age of twenty-three: ‘I found myself in the year I retired from the Guards the owner of a fine property and a good income. I had likewise excellent health and the Irishman’s capacity to enjoy life, so it is small wonder that I threw myself into the pursuit of pleasure and determined to have a thorough good time.’ This he proceeded to do, for the rest of his life – and when his own funds ran out, as they quickly did, he found means, and people with means, to finance him. His greatest gift, it would seem, was this capacity to get other people to pay his extravagant bills.

Derry certainly also had a capacity to make friends. His enthusiasm for his pursuits and pastimes was infectious. When he was a boy, it was hunting, fishing, shooting, cock-fighting and drinking. ‘Those distant days were very happy ones,’ he wrote. ‘I used to hunt by moonlight with Dick [his brother], and as this happened after dinner, reckless riding was more likely than not.’ The book is full of descriptions of drinking bouts. ‘When I was a young man the Irish took their whack just as their forbears had done – we were used to rough nights.’ On one such night Derry and his friends mercilessly left a man whom they felt had offended them to sink up to his neck in a bog.

Another impression Derry was happy to give was that he was a great ladies’ man. He tells a story of a woman whose husband was badly injured in his private parts in a fight. Derry later encounters the wife, looking miserable. When he realizes who she is, and why she’s so gloomy, he says to her, ‘If I wasn’t due at the meet, I’d just get off my horse and have some further conversation with you.’ She replies: ‘Ah – ah, I know ye now. Sure and you’re Master Derry. Well well, I’ve always heered tell that you’re an obleeging blackguard!’

He was a gambler. His younger brother once arranged a cock-fight in the kitchen of the courthouse in Monaghan, while acting as secretary to the Grand Jury. They also bet on badger-baiting. Two badgers would be let loose together, and then, Derry said, ‘the fun commenced’. He tells a story of a local lawyer coming to dinner at Rossmore. After dinner they let the badgers loose with the dogs. The lawyer toppled drunkenly into the pit where the dogs and badgers were fighting. ‘Joe fell right in the middle of the combatants, and, once down, he couldn’t get up. All we could see was Joe’s inert form with any number of dogs running over it, snapping and yapping at the badgers.’ This was thought hilariously funny.

One of the few dates in his book is the year he started racing – 1878, when he was twenty-five. By then he had been lord and master of Rossmore for four years. He started on the Curragh, in Co. Kildare, and later trained at Epsom and Newmarket in England. Racing became a passion to him, and also the means of losing an enormous amount of money. He did have some successes, however. His greatest win was the City and Suburban in 1882, with his horse Passaic. This coincided with a significant interview with his future father-in-law, Richard Naylor. Derry was not able to watch his horse win, as he had elected to go that afternoon to ask for the hand of Mr Naylor’s elder daughter Mittie. He describes the interview:

I found the old man lying on the sofa … pretending to be very ill. It was then three o’clock, and as I knew that Passaic had won the race, I greeted him by saying, ‘How are you? I’ve won the City and Suburban.’ He huddled himself up and just grunted by way of an answer. Said I, ‘I’ve come to ask you to allow me to marry your daughter; that’s why I’m here.’ ‘Go away, Rossmore,’ he replied in peevish accents. ‘I tell you I’m far too ill to discuss those sorts of things.’ But suddenly his sporting instincts overcame his grumpiness, and he jumped up like a two-year-old, saying, as he did so, ‘But have you really won the City and Suburban?’

Naylor was an extraordinarily wealthy man. The house in which that interview took place was Downshire House, his London residence, in Belgrave Square. He was for a time the Master of the Pytchley hunt in Northamptonshire – an influential position. Naylor had two eligible daughters. Derry wrote of him: ‘He hated the Irish “like fun”: in truth, he detested most men and especially those that came after his girls. Personally I don’t believe he really minded whether they got married or not: it was merely his dislike of “forking out” the settlement money which made him so loth to part with his daughters.’ And this is the crux of the matter. Naylor was probably aware that the most attractive thing about his daughters was the money they would get from him when they married. He was likely to be extremely suspicious of any young man coming after them, particularly a young rake-about-town like Derry. He was also, as Derry claimed, prejudiced against the Irish. At the height of the Great Famine in Ireland in the late 1840s, Naylor sent a boat over to Ireland, filled it to the brim with unemployed labourers, and sailed it back to Liverpool, thereby hoping to equip himself with cheap labour, while giving the workers the means to eat. But the scheme failed: the men, for whatever reason, wouldn’t work for him. Naylor shipped the workers back to Ireland and vowed to have as little as possible to do with the Irish from then on.

Derry claimed that ‘it didn’t matter to me if Mittie Naylor hadn’t a penny in the world: I was in love with her, and we determined to get married whenever the opportunity presented itself’. This suggests there was some strong opposition. The opportunity only presented itself when she reached twenty-one, and was free to make her own decisions. Her father’s opposition to the match would have made it much more dramatic and exciting for her. Derry was, in her eyes, a romantic character: a young peer (whereas Naylor was a commoner whose family had come to prominence through trade and banking); the owner of a grand castle in Ireland; a dashing, courageous, good-looking fellow who moved in the highest society; a former officer in the Brigade of Guards; a man with an inherited position of influence in his own county – all this, and, as well, he was fun to be with, flirtatious, outrageous, a bit of a risk, and not at all boring to a girl who had been brought up to respect horses and hunting as greatly superior to books and learning. She was dazzled by the outward show of the man, and he did everything he could to foster her image of him as a man who would dare all to capture her.

To have persuaded Mittie to be his wife was a great achievement for Derry, and whatever he might have said about it not mattering to him whether or not Mittie had a penny in the world, he was certainly the one man in the world who needed a rich wife. Years later Mittie was to say, ‘All I ever seem to do is write cheques.’ In ThingsICanTell, apart from his encounter with her father, Derry scarcely mentions Mittie, except to explain that she gave up hunting after a serious fall which concussed her for several hours. He writes of his daughter Mary only once, and of his sons not at all, except, on the final page, to say, ‘I am fortunate in possessing a charming wife and the best children in the world.’

Richard Naylor, when he looked so glum the afternoon Derry came to call, had assessed the situation accurately. Derry was a spendthrift, and needed a large supply of ready cash. At the time of Derry’s wedding, Naylor was one of many people known popularly as ‘the richest commoner in England’. As the years went on, his relationship with Derry went from bad to worse.

Richard Naylor founded his racing stud at Hooton in the 1850s, proposing to race on a big scale. Hooton was close to the Marquis of Westminster’s stud at Eaton Hall, and in 1860 Naylor bought six of Lord Westminster’s yearlings. One of these became his most famous and successful racer, Macaroni, who won the Derby in 1863. Naylor cleared nearly £100,000 by backing Macaroni when he stood at 50 to 1 to win at Epsom.

After three years of racing, Naylor put Macaroni to stud at Hooton, and soon after that he added to his stud the most famous stallion of all time: Stockwell. Naylor bought the horse at the end of his racing career in order to breed from him. The fee for Macaroni’s services was thirty guineas. At the date of the stallion’s death no fewer than ninety-two of his daughters were included in the stud-book.

Hunting was Naylor’s other great passion. In order to hunt with the Pytchley, he bought Kelmarsh Hall in Northamptonshire in 1875. He did not embellish Kelmarsh, a fine Georgian house, with Victorian elaborations, apart from building on a ballroom and importing a lot of ugly Italian marble for the chapel. (In 1891 Mary Westenra was christened there, as a baby of two months – Richard Naylor’s first grandchild.) The Prince of Wales would have hunted with the Pytchley, and probably stayed at Kelmarsh. He was certainly a friend of the Naylor daughters, Mittie and Doods. (In 1890 Doods was a guest in the house party at Tranby Croft at the time of the notorious cheating scandal at the game of cards in which the Prince of Wales was playing.)

Kelmarsh Hall was ‘the house on the hill’, a classical Palladian villa designed by the great architect James Gibbs, who was responsible for St Martin-in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square and the marvellous Gibbs building in King’s College, Cambridge. The house was sold in 1908, when Mary was seventeen.

Richard Naylor was of his time: a man who wished to impress the world with the size of his fortune. Hooton Hall was a perfect counterpart to Rossmore Castle. Before Naylor bought Hooton in 1848 and laid his enlarging hand on it, it was a respectable square-fronted Georgian mansion. He proceeded to make it into a palace. Long wings were built on either side of the main block; a chapel was incorporated into one, and a vast sculpture gallery into the other. A great tower with a cupola on top embellished the skyline. Urns and statues were liberally scattered along the top of the new balustrades around the roof, and pillared porticoes added to the front garden.

All this work by Mary’s grandfather Naylor was being carried out at the same time as her grandfather Rossmore was enlarging Rossmore Castle, on an equally extravagant scale. Why did they do it? Was it simply to show off their wealth and importance? Rossmore Castle was poorly and cheaply constructed. The money was not there to make a long-lasting job, and less than a hundred years later the castle had to be pulled down. Hooton Hall was eventually destroyed too, but for a different reason. It was used to house the R.A.F. during the Second World War, and was left in a bad state. The Air Ministry sold off some of the land, and an enormous Vauxhall car factory was built in the grounds. It had been left to Derry Rossmore’s son Richard, rather than to his elder son William, who became the sixth Lord Rossmore, because by then Richard Naylor had become so sick of Derry’s extravagances that he vowed that not a penny more of his would go to financing the Rossmore estate. Hooton Hall was pulled down in 1946. Rossmore Castle was pulled down in – 1946. Less than a hundred years of splendour – and in the midst of that extravagance the child Mary Westenra was born, at a time when it must have seemed to her grandparents and parents that their dynasties were set to continue for centuries.

3

Derry and Mittie

When Derry Rossmore married Mittie Naylor in 1882 he bore her back to his romantic castle deep in the bogs of Ireland. It would be fascinating to know how she reacted as she arrived at Monaghan station, to be greeted as her daughter Mary would be twenty-eight years later, after her marriage to Abe Bailey. Mittie was the young, handsome, wealthy bride of the great landlord of Monaghan; the chatelaine-to-be; the employer of a vast army of outdoor and indoor servants; the wife of the man to whom the rents of the town were paid.

Having been brought up by Richard Naylor, Mittie would have had her own ideas about how large houses should be run. Derry’s mother, the redoubtable Julia, who was left a widow with six small children but who nevertheless was able to persuade George Stacpoole to become her second husband, must have been relieved to see the rich young heiress appear, and to realize that the burden of running Rossmore on a shoestring was to be lifted from her shoulders.

Derry held a title which probably meant nothing at all to Mittie: he was the County Grand Master of the Loyal Orange Order of County Monaghan. It was in this capacity that, in the year after his marriage, Derry achieved his greatest moment of fame. The Orange Order had been founded in County Armagh in 1795, a time when loyal Protestantism felt itself under threat from the Catholic ‘Defenders’ and the United Irishmen, who opposed being ruled from England. The men who founded the Order wanted to ban Catholics from the local linen industry, and they wanted to keep in with the Protestant ascendancy, who were their landlords. Baron Smith, in 1813, described the attitude of Orangemen as ‘a spurious and illiberal loyalty which grows up amongst the vulgar classes, and which is very turbulent, bigoted, riotous and affronting, very saucy, and overbearing, almost proud of transgression, necessarily producing exasperation, and often leading to the effusion of blood’.

The Baron’s remark about ‘the vulgar classes’ notwithstanding, and in spite of his father’s and grandfather’s support for Catholic Emancipation and O’Connell, Derry Rossmore did not think it odd, in the early days of his manhood, that he should be the figurehead in Monaghan for such an organization. In the Ulster border counties the Protestant ascendancy believed it their duty to give a responsible lead to their tenantry. It was thought very important that the Protestant influence should be paramount, and Orangeism was one means of ensuring this. Derry probably didn’t think much about the significance of being the County Grand Master. It is possible that the position went with his title as Lord Rossmore.

Derry’s great day came in 1883. The nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell, at the height of his power, had announced a meeting to be held in a field outside Rosslea in Co. Fermanagh, on 16 October. Derry Rossmore, together with a Mr J. Wallace Taylor, issued a counter-proclamation. Derry was its author. It read:

The late Invincibles and Land Leaguers are afraid to enter Monaghan, but they have flooded your county with proclamations asking your attendance at Rosslea on 16th October, to hear their treasonable speeches.

Attend there, with Sir John Leslie, Colonel Lloyd and myself, to assist our Fermanagh brethren in supporting their rights, and oppose the rebels to the utmost, showing them that the Orangemen are, as heretofore, loyal to England. They declare that you are as ready to obey them as their dupes in the south, but we will show them, as did the Tyrone men, that they are liars and slanderers. Boycott and Emergency men to the front, and down with Parnell and rebellion! God Save the Queen!

He inspired 3000 Monaghan men, who were joined by 4000 Fermanagh men and another 1000 men on the road, to march to the field adjoining the one in which the Parnellites – over 3000 of them – had assembled. On the way they were confronted by the Resident Magistrate, a Captain McTernon, who attempted to prevent the Orangemen from continuing. Derry refused to give ground, asking the R.M. if he had any authority to prevent them from using that road; the R.M. had to say that he had none. McTernon said later that bad language and threats had been used by Lord Rossmore’s companions, but not by his lordship himself. So, despite his protests, the vast march continued on its way. Derry later explained in his book that the two fields were separated by a stream with a bridge across it, and that it was obvious to any fool that the bridge could easily be defended by only two men, so there was no danger of its being crossed. The chair at the Orange meeting was taken by Viscount Crichton, the eldest son of the Earl of Erne, of Crum Castle, Co. Fermanagh, and the resolution was proposed by Lord Rossmore, that Orangemen ‘solemnly bind ourselves to maintain the union between Great Britain and Ireland, and resist in every way and by all means, any attempt to place Ireland under a government of murderers, butchers, and socialistic rebels’.

The R.M. asked Derry not to march back along the same route. Derry knew his followers would think this a capitulation, but he eventually agreed, and (according to his book) made a speech to the assembled throng telling them that, if they disobeyed, and went back the way they came, ‘You shall only do so over my body.’ They did as he asked, with no further trouble.

Amazingly, the whole incident passed off in a peaceful manner, and the day became a personal triumph for Derry, who was asked to address meetings and attend rallies all over the north of Ireland. When he went by train to Belfast, at every stop on the way there were crowds waiting to cheer him, and he addressed them from the steps of his carriage. Shane Leslie, in his book TheFilmofMemory, wrote: ‘Had Rossmore possessed any eloquence, he could have seized the leadership of Ulster at that fervid moment.’

Derry’s foolhardy Orange outing had one or two unfortunate results. The Resident Magistrate was angry that his authority had been flouted. A complaint was made to the secretary of the Lords Commissioners for the Custody of the Great Seal of Ireland, and Lord Rossmore was told he would be removed from his position as Her Majesty’s Commissioner of the Peace. Even after receiving several letters of explanation as to his actions, the secretary was adamant that Derry should be deprived of this office. J. Wallace Taylor, his co-marcher, wrote a book called TheRossmoreIncident in which he provided a list of all the magistrates in different counties of Ireland – titled aristocrats, mostly – who wrote to declare their support for Derry in his actions, and their disapproval of his demotion. Despite this support, Derry was not reinstated as a magistrate for several years.

We can only guess at the life Derry and Mittie lived in these early years of their marriage. The pattern of their year was clearly defined. From August to March they were in Ireland. From April to July they were in England: in London for the season, which lasted from May to the end of June, and at Cowes week, which would have been important to them, as Derry’s father had owned large yachts. Race meetings, and house parties in different parts of England with the Prince of Wales’s set, filled up more spaces in their social diaries. Derry’s book is filled with stones about the Prince, whom he often met at the races.

There are theories among Mittie’s descendants that she was a much closer friend of the man who was to become Edward VII than her husband was. Hints have even been made that she might have been his lover – and that her first child, Mary, might have been his.

Mary’s eldest daughter, Mary Ellen, believed that Mary knew of her mother’s sexual adventures, which shocked her to the extent of making her almost paranoically prudish about all things to do with sex in her own and her children’s lives. This side of the family believes that Mittie slept with the Prince of Wales.

None of Mittie’s children resembled each other – feeding the view that they may have had three different fathers – and none inherited Derry’s stammer, which he claimed was a family trait. Some descendants believe that Derry was ‘too drunk’ to perform his marital duties, and that this forced Mittie, after eight years of trying and failing to produce an heir, to turn elsewhere. This seems an unlikely explanation, however, as Derry was known to have several mistresses. Desmond Leslie said Derry ‘kept a French lady in Portadown. You see, you could hop on a train, it was only five stops up the line, about half an hour’. Desmond’s father, Sir Shane, said of her, ‘The poor lady looked at the rain every day, falling on the Orange parade, and she died of ennui.’

Although it is likely that both Derry and Mittie had extramarital affairs, there is no evidence, beyond family tattle (perhaps born of wishful thinking), that Mittie had an affair with the Prince of Wales. There is some circumstantial evidence to the contrary. In 1889, the year before Mary was born, the Prince had fallen madly in love with Daisy Brooke, the wife of the future Earl of Warwick. He spent the next six years of his life ensnared by her charms, and even after the affair became platonic, he was her devoted slave. He wrote to her in 1897: ‘How could you, my loved one, imagine that I should withdraw my friendship with you? On the contrary, I want to befriend you more than ever … my own lovely little Daisy [my wife] really forgives and condones the past as I have corroborated what you wrote about our friendship having been platonic for some years.’

Mittie’s life can’t have been easy, complicated as it was by her father’s contempt for Derry, and her position as go-between, continually having to provide her father’s money for her husband’s profligate ways. Alcohol and infidelity would only have made things worse. It was into this complex relationship that Mary was born, on 1 December 1890.

4

Mary’s Childhood

In spite of the underlying troubles of her parents’ lives, Mary looked back on her childhood as idyllic, and this was because of the magic of Rossmore. As she grew up in her enchanted castle, surrounded by the towering woods and the lakes of the estate, where she was free, yet safe, there can’t have been much her childish heart desired that was denied her. This was why for Mary, in later life (spent mostly in England and South Africa), everything Irish was good. Ireland – Rossmore – was a place where, from the perspective of older, sadder times, it seemed she had always been happy.

Her relationship with her father was always good, that with her mother much less so. She and Derry shared a love of horses, outdoor sports and high-speed exploits. Mittie had given up hunting before Mary was born, and she might have felt twinges of jealousy as she watched her husband and daughter so rapturously enjoying a sport she had once loved so much herself.

Hunting was Mary’s passion from an early age. In Monaghan there had existed a pack of hounds known as the Monaghan Harriers – which meant that their quarry was not foxes, but hares. It was disbanded for several years, but in 1904 there appeared a notice in the local paper, the NorthernStandard: ‘A meeting will be held in the Westenra Arms on Monday next at 12.0 to take into consideration the possibilities of re-starting the Monaghan Harriers for the coming winter. Those interested in the matter are requested to be present.’

The Westenra Arms, a hotel in the centre of Monaghan, just beside a memorial to Mary’s uncle Rosie, belonged to Derry. Probably it was at his instigation that the meeting was held. Certainly he would have been there, and so would Mary, aged thirteen. Derry and Mary were to be seen at almost every meet of the Monaghan Harriers from then on, the first meet being on 5 November 1904, three weeks before Mary’s fourteenth birthday. She was out hunting all through the winter of 1905, which shows that she was not away at boarding school, but being educated at home during that winter.

Mary did attend Heathfield School, Ascot, for one disastrous term in 1906; she hated it so much that she ran away, and she was not made to go back. The one event we know about from her time at Heathfield was that she was confirmed in Holy Trinity Church, Bracknell, on 18 November 1906, just before her sixteenth birthday.

A girls’ boarding school, however well run, however fashionable, must have seemed a prison to a child whose instincts were all for adventure. To run away takes initiative and courage, a paradox summed up by T.S. Eliot in his play TheFamilyReunion:

In a world of fugitives

The person taking the opposite direction

Will appear to run away.

Mary was allowed to return to her horses and her hunting, and was taught by two remarkable sisters from Russia, who came to Rossmore and continued her education there. Alma and Yelma Hemmerlé came from an aristocratic Franco-Russian background. Mary must have become very fond of the sisters, because years later she was still in touch with them and both her son and grandson remember meeting them. Through them she learned to speak good French. Although she is not remembered now as being particularly intellectual, she was well educated by the two Misses Hemmerlé, and books of hers, annotated in her own handwriting, show that her reading was eclectic and intelligent.

But Mary was basically an outdoor child. Before the Monaghan Harriers were re-established, she took part on horseback in the Monaghan County Show, which took place every September on the Rossmore estate. The year before, in 1903, when Mary was twelve, her father had constructed a new jumping enclosure in Rossmore Park, and it was inaugurated on 10 September 1903, with displays of driving and horse jumping and tug-of-war competitions, accompanied by the band of the Third Battalion of the Irish Fusiliers. Admission was sixpence, with 1s. 6d. extra for the grandstand enclosure. Mary performed sidesaddle, as she always rode, on one of her favourite horses. In 1907 Mary and her father both competed in the Monaghan County Show. Mary won third prize in the jumping competition on her horse Tullaghan, and Derry won first prize in the Monaghan Harriers competition.

A picture of Mary, looking most charming and feminine in a wide-brimmed flowery hat and diaphanous accordion-pleated dress, appeared in the IrishSocietyandSocialReview of 13 March 1909. The picture was accompanied by a description of Mary as

a girl who is very cheery and bright, who loves dancing and music. She is voted ‘a real good sort’ among her friends. She has a good seat riding, good hands, and can put a horse well at a fence and gallop it across a field. She has had a fair amount of hunting with her aunt, Miss Naylor, and among hunting people that will speak for itself. She has a 20 bore shotgun with which she is making rapid progress towards becoming a good shot, and is very keen on the sport. She is fond of all games, such as lawn tennis, golf etc. (BUT) She has been doing too much lately, and has in consequence been on the sick list, and has been told she must ‘go slow’ for a year.

There is no evidence that she ‘went slow’. Just before her nineteenth birthday Mary achieved the remarkable distinction of being elected to the Mastership of the Monaghan Harriers. There must have been very few Masters anywhere in these islands who were only eighteen, and even fewer who were eighteen and female. It was a terrific achievement, and says a great deal about her character. She was not particularly imposing to look at, being only five foot four, slight and feminine looking, with a lithe figure. But her appearance was deceptive. Already she was renowned for a delight in taking risks. She is still famous in that part of the world for having jumped the fearsome ‘Double Jump at Magheranny’.

An announcement in the NorthernStandard of 19 December 1909 read:

The meeting of the Monaghan Harriers on Saturday was at Summerhill, and the new Master, the Hon. Mary Westenra, was enabled for the first time to take up her position. Miss Westenra was up till a week ago in London, in attendance on her mother, who was suffering from indisposition, but her ladyship is now happily recovering. Miss Westenra was cordially welcomed on Saturday … the remarkable feature of the meeting was the number of dogs present.