Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In reading these tales we are reminded of the intricacies of time; its ability to propel us to adulthood through the brief blaze of college years, as well as its propensity to continually encircle us with age-old issues of class, camaraderie, love and civil liberties. Contributors: Tom Doorley, Aine Lawlor, Hugo MacNeill, Linda Hickey, Dermot Horan, Eoin, McCullough, Carl Nelkin, Shane O'Neill, Jackie Kilroy, Pauline McLynn, Lynne Parker, John Reid, Katie Donovan, Alan Gilsenan, Declan Hughes, Austin O'Carroll, Nick Sparrow, Patrick Wyse-Jackson, Dermot Dix, Luke Dodd, Anne Enright, Sean Melly, Luke O'Neill, Vandra Dyke, Sallyanne Godson, Quentin Letts, Jane Mahony, Michael O'Doherty, Rosita Boland, Rosheen McGuckian, Patrick Prendergast, Heidi Haenschke, Fiona Cronin, David McWilliams, Ivana Bacik, Michael West, Leslie Williams, Brian F. O'Byrne.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 399

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

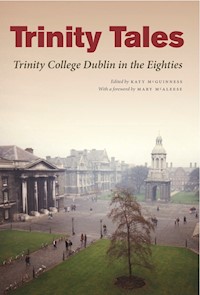

TRINITY TALES

Trinity College Dublin in the Eighties

edited byKATY McGUINNESS

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

EDITOR'S PREFACE

The received wisdomis that Dublin in the eighties was grim, but I don’t remember it as such – and there is very little by way of misery memoir in the contributions that go to make up this, the third volume ofTrinity Tales. Then, as now, Trinity was a great place in which to sit out a recession.

The previous Trinity Tales, also published by The Lilliput Press, gathered together contributors who had been in college during the sixties and seventies. By the eighties, Trinity was no longer a controversial choice for Catholics, and many students were drawn from the Dublin middle classes. Heidi Haenschke, arriving in Trinity from the US for her year abroad, was surprised to find so many of her classmates living at home and commuting to college. For this cohort, summers abroad such as those described by Linda Hickey, Jane Mahony and David McWilliams, allowed an escape from under the parental roof. Migrant Trinity students found their freedom in the factories of Germany, and the bars and restaurants of London and New York.

I had already visited Trinity on numerous occasions before I enrolled in the Law School in the autumn of 1979. As co-editor (with my school friend, Paula Flynn) of the Wimp Wonder Comic fanzine, I had been blagging my way into gigs all over town since I was fifteen. I saw the Buzzcocks and The Worst in the JCR, and The Clash in the Exam Hall. And, unlike many who claim to have been there that night, I can prove it, thanks to a clipping from the next day’s Evening Press in which I’m wearing a fetching plastic bag celebrating HM Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee. ‘Spitting At The Band, In Trinity’s Hallowed Cloisters’ read the caption; it caused a stir when it appeared on the noticeboard in Holy Child Killiney the following Monday morning.

My brother, Paul, had attended Trinity a decade before me. (He writes about this inTrinity Tales: Trinity College Dublin in the Seventies, edited by my sister-in-law, Kathy Gilfillan.) He left Trinity without a degree, not that this appears to have been any impediment to his subsequent career as the manager ofU2. My other brother, Niall (who died in 1993), had also failed to graduate from the University of Loughborough. And so the weight of parental anxiety weighed heavily on my shoulders. My instructions were clear. I was to attend all my lectures, have nothing to do with Players, where Paul had apparently spent far too much time, and I was to stay away from Brendan Kennelly, who had refused him academic credit at the end of his third year, meaning that he could not sit his exams and lost his grant. Reading over the accounts of this golden age of Players in the accounts of Lynne Parker, Declan Hughes and others, I have some regrets now that I was such a biddable child. My path never crossed Kennelly’s.

I met Sarah Bailey on a library tour. She was so grown up (matching shoes and handbag) that I assumed her to be a mature student. In fact, she was seventeen, like me. We went for coffee in Switzer’s afterwards, and spent much of the next four years gossiping in either the Kilkenny Design, or the Bailey, or O’Neill’s or Murph’s, often in the company of classmates Eoin McCullough, Michael Cush, David Cox and Nicki Harvey. I am lucky that they are all still my friends. Sarah was to be avoided at exam time, however, as her bluffing skills in relation to arcane legal rules were legendary and could wrong-foot you. We lawyers avoided student politics, by and large, and had little time for SU president Joe ‘Duffle’ Duffy and his speechifying from the steps of the Dining Hall.

I went to my first Trinity Ball in a long, jade-green, Grecian-style dress and very high heels. Arriving at the pre-Ball drinks, I was greeted by veterans Simone Stephenson and Adrienne Foley in simple silk camisoles, trousers and flat pumps. I made that mistake only once.

My father died suddenly during the summer after my first year. Money was tight and my hopes of getting rooms were dashed. By way of compensation, a white Renault 5 was purchased, and I careered around Dublin without much consideration of the drink-driving laws, such as they were at the time. Paula (by then studying fashion and textiles in NCAD) and I set up Dublin’s first singing telegram business, and drove the performers – law students Anne O’Neill, David Cox and John Coulter, and Players’ ‘talent’ including Gary Jermyn, Una Clancy and Arthur Riordan, to their appearances. The money I earned, as well as from selling advertising for Piranha and waitressing in Barrels in Dalkey kept me going.

I spent a couple of summers in New York, and my head was turned. After four years in Trinity I knew Dublin and everyone in it far too well, and could not leave soon enough. I was on a flight toJFKthe day after my final exam. For the next decade, I was one of those ex-pat yuppies breezing into the Shelbourne for Christmas drinks with the old gang from Trinners that Alan Gilsenan remembers resenting. And by the time I returned to live in Dublin, and walked through Trinity once again, it felt as if I had never been a part of it at all.

The two concluding essays are by Patrick Healy and Gerald Dawe, neither of whom is a Trinity graduate, yet both very much part of the college community. As before, the royalties from this book go to the Long Room fund of Trinity College.

At The Clash, TCD Exam Hall, 21 October 1977. Left to right: Paula Flynn, Katy McGuinness, Paul Byrne and Rachel Pigot.

Katy McGuinness(TCD1979–83; Legal Science) studied for anLL.M. in trade regulation at New York University School of Law and was admitted to the New York Bar. She practised law in New York before moving to London, where she was head of business and legal affairs at Palace Pictures. Back in Dublin, she produced several feature films. She holds anMAin English (creative writing) from Queen’s University, Belfast. As a journalist, she has written forThe Irish Times,Irish Independent,Sunday TribuneandSunday Times, and is the restaurant critic ofThe Gloss. She is co-author ofThe Irish Beef Book(2013). Katy is married to architect Felim Dunne; they live in Dún Laoghaire with their four children.

FOREWORD

Mary McAleese

My motherand her siblings have sixty children between them. I am the oldest of nine. Where two or more of us siblings or cousins are gathered together, discussing our parents or grandparents, the variety of memories and opinions, the conflicting views and analyses, could make a body wonder if we are talking about the same people and places. Well, we are and we aren’t. From the oldest to the youngest of the sixty of us, there is a difference of over thirty years. A lot changes in thirty years. Add personalities and interests and the vagaries of life to the mix and the shared genetic landscape of familiar noses or build or colouring cannot conceal the strong gravitational pull of differentiation – in sixty different directions. And so it is with gathering memories of Trinity College. This book is the third in a series of contemporary reminiscences about an institution that has had a place in Irish society for over four hundred years. Its boundary walls have long since created a unique island at the heart of Dublin city.

Tens of thousands of tourists, locals, students and staff meander through there every day, accreting memories as they go. Once it catered for a tiny elite and was no bigger than a small secondary school. Today its cramped campus is stuffed with elegant old edifices and brash new buildings cheek by jowl. The Campanile, the Exam Hall, Botany Bay and the Old Library are still more than a little righteously disdainful of the ugly Berkeley Library of the 1960s and the grim Arts Block of the 1970s, but these buildings mark the watershed between elite and mass education. They also mark the beginning of state investment in Trinity College, the growth of new disciplines and postgraduate education, the laying of the groundwork that would see the college transformed in thirty years into a serious high-level player on the global university stage. The eighties really were the start of something big in Trinity.

It seemed at times in the eighties as if the landlocked campus was destined to become a permanent building site and no doubt future volumes will speak of the new, smart, architectural gems that populate the Westland Row end of college, not least of which is the much-needed new Dublin Dental Hospital, which was endlessly discussed in the eighties but did not appear until the end of the nineties. Its existence is a testimony to the visionary persistence of Derry Shanley, the former dean of the Medical Faculty who masterminded the radical modernization of buildings and curriculum, while managing to look like a twelve-year-old altar boy.

However, all those swanky new builds of the nineties and noughties are for another decade of reminiscences; in the eighties most of them were just notions jump-started to life by the formidable raw energy, ambition and necessity unleashed by widened access to education. The old world of prim, presumptuous ease that was the alleged delight of former generations was put to flight with scary rapidity, leaving some bleating on wistfully for years about a putative golden generation that was truly educated as opposed to those who followed, blah, blah. This was for the most part self-regarding shorthand for the last tiny petted cohort of students that was rudely supplanted by the arrival on the scene of the more numerous first-generationers.

These were the education-hungry youngsters from humble and modest backgrounds, whose parents never had the chance of second- never mind third-level education and who were the real fruits of free second-level education. The doors of Trinity were thrown open to those ‘intelligences brightened and unmannerly as crowbars’ who ‘would banish the conditional forever’, to borrow from Seamus Heaney’s description of the same phenomenon north of the border a generation earlier in his poem ‘From the Canton of Expectation’.

I had arrived in Trinity in 1975 as the last of the sixties generation moved on and the cut and jib of things began to be refashioned in the image and likeness of the new owners of memories of Trinity. One major shift was in the pattern of Christian worship in college. Shortly before, Father Brendan Heffernan had been appointed the first-ever Catholic chaplain to Trinity. The beautiful Anglican College Chapel was generously offered on a shared basis to the Catholic community in college for daily Mass. Thus grew the strange spectacle of a not insignificant number of staff and students dashing from lectures across the lethal cobbles of Front Square to be in time for Mass at the eccentric time of five minutes past one each weekday.

The Catholic Church’s ban on Catholics attending Trinity had been dispatched in 1970 to the same bin of historic vanities as the original college ban on Catholics and Dissenters. So the eighties, though characterized by some as an era when the college became homogenized and less cosmopolitan, was, in fact, a time of pelting new vitality for those who actually worked, studied or lived there. A buoyant, ground-breaking ecumenical spirit was the hallmark of Trinity’s chaplains of various denominations. It was a lived communal reality of oneness, a terrific team ministry, which I was never to encounter to the same extent elsewhere in Ireland despite valiant efforts of the likes of Cecil Kerr’s Christian Renewal Centre in Rostrevor, or Ray Davey’s Corrymeela Community, or the Glencree Centre for Peace and Reconciliation.

Not until I encountered the Catholic Caravita community in Rome thirty years later, with its hearty ecumenical relationships, did I find such a relaxed and genuine Christian unity. In the eighties, however, uniquely on the island of Ireland it was Trinity College that led the way, more than playing its part in setting a new agenda for ecumenical parity of esteem. Through that difficult, violent decade it bore witness to the values of tolerance and mutual respect in contrast to the roiling sectarian conflict that continued to poison the atmosphere and paralyse the political maturing of relationships within the North, between North and South, and between Ireland and Britain.

Trinity’s lively intellectual discourse showed evidence of real if not always well-informed interest in Northern affairs but the level of benign ignorance was no worse than elsewhere and there was always a challenging debate on in the Hist or the Law Soc, where passion and repartee took the place of forensic scrutiny rather like your average parliamentary debate only almost invariably wittier and more entertaining. One face, one voice, dominates my memory. The young baby-faced, multi-curled Brian Lenihan. He had won Schol at the end of the 1970s; his was a brain of legendary and amazing capacity. Funny, savvy, passionate and knowledgeable on a very eclectic span of subjects, he pretty much outshone the rest. That was no small feat for his peers were a bright and high-achieving bunch, many of whom have made a national and international imprint. But he had a very natural charm, decency and graciousness that alongside his brainpower was to earn him, in his student days, the widespread respect that characterized his later legal and political career.

The eighties saw the stirrings of computer literacy. There was reputed to be a Computer Something Department somewhere in college though we had no idea what went on there and no idea of how it would shortly revolutionize our lives. Our wonderfully maternal if occasionally scolding Law School secretary, Margot Aspel, was tormented by a brute of a typewriter, correcting fluid and those horrible black carbon-paper packs with ‘flimsies’ and other time-consuming tyrannies, which included all of us staff and students, for our favourite place was in her office drinking her home-made lemonade or eating her delicious little cakes. Unless, of course, she was in a mood, in which case most of us would have chewed our elbows to the bone rather than venture across her door. I still miss her.

Meanwhile, I mastered the first of Alan Sugar’s cheap Amstrads and ventured not very boldly into the computer age. When at the end of the eighties I moved to the Queen’s University of Belfast and enquired of the Northern Ireland Bar Library whether it offered online services and computer access to barristers, the tentative reply was that they had the electric plugs. How quickly it became unthinkable to teach without computers, the Internet, wi-fi, online libraries and all the rest. In the eighties in the Computer Something Departments in Trinity and elsewhere a new generation of thinkers and doers was, almost unnoticed, changing the trajectory of our lives. Golden generations, one after the other and one more remarkable than the next.

A FLASHY PLAYER

Tom Doorley

I thinkI was only ten when I decided that I wanted to go to Trinity. On my weekly visit to a great-aunt in Pembroke Street I would wander through Front Gate, school satchel swinging, and amble along to Lincoln Gate. It was exotic; I liked that. I liked the squares and the buildings and their quietness and elegance. Many of the students – this was 1970 – looked as if they were refugees from the ‘summer of love’ and had just removed the flowers from their hair. My inability to achieve anything approaching a pass in a maths exam prompted my headmaster to point out that Trinity would not require me to have mathematics – provided I had a pass in Latin, something I could manage in my sleep. Egged on, I’m sure, by the entire maths department at my school, the headmaster suggested that I might give mathematics a miss at Leaving Cert. and concentrate on Virgil and Cicero. I didn’t hesitate.

TheTCDMatric was my salvation. It rather grandly ignored the Leaving Certificate syllabus in its entirety and I fell upon it, as Wodehouse would say, with glad cries, in 1976 when I was in the fifth form. When I was awarded the only distinction in English that year, I was convinced thatTCDhad, with laser-like acuity, recognized my peculiar genius. It must, I decided, be a distinctly superior kind of joint. But, of course, it never made the same mistake again.

I arrived to register in the School of History in the autumn of 1977, stepping off a yellow number 11 bus and into a campus of a mere 4500 students. There was no Arts Block; Fellows’ Square was a big building site. We history students started our academic careers in the Museum Building, amidst the fossils and the skeletons. As far as academic matters were concerned it was, in my case at any rate, an example of youth being wasted on the young. Some of the finest brains in the land were on hand to teach us and yet I failed to be gripped by the story of the Guelphs and the Ghibellines and the emergence of medieval Europe.

But there were pleasant distractions. Most of us boys had been educated at all-male schools that smelled of sweat, ink and cabbage. Girls were galactic creatures who sprinkled the sidelines of cup matches at Donnybrook with fairy dust; they imparted a sensual frisson to even the dullest of inter-school debates. Now, they were classmates and we had to adjust to their regular proximity. People from my old school, Belvedere, made a point of eschewing each other for the first term or so, in an attempt to avoid falling into a clique. I recall the late Brian Lenihan saying in a very earnest stage whisper – to the puzzlement of everyone within earshot, i.e. most of Front Square – ‘We mustn’t keep meeting like this!’

Most history students laboured under the illusion that doing aBA(Mod) in history involved learning history. In the fullness of time, a majority realized that what we were learning was, in fact, a set of skills: the ability to research, refine an argument, marshal thoughts, think clearly. I was in my thirties before I realized that I had learned a great deal during my four undergraduate years. It just wasn’t what I had been expecting.

At the time, however, I came to accept that I was going to end up knowing more and more about less and less. I developed a vast and wholly unexpected enthusiasm for the wool industry in medieval England – purely because my tutor, Dr Christine Meek, was a superb teacher. I ended up producing a mini-thesis on how the cloth industry helped to finance EdwardIII’s military campaigns. I still have a mild sense of disbelief when I realize that I managed to pull this one off.

Some of us were lucky enough to be taught by R.B. McDowell, when he was still in full flight. When you stepped into his office you were – literally – ankle-deep in papers and books; he had an aversion to using shelves. On one occasion, when I had gone to collect an essay, he told me brightly: ‘You take that side of the room, I’ll take this and I’m sure we’ll turn it up eventually.’ It took less than an hour. He taught a brilliantly random and exciting course under the broad title of ‘Ireland in the Age of Imperialism and Revolution’. He had a marvellous talent for digression, a quality I have always regarded as undervalued. Some other courses failed to grip me. I drove Professor Louis Cullen, the great expert on Irish economic history, to distraction. On one occasion when reading a seminar paper on the price of potatoes in the nineteenth century, he asked me, rather sharply, to ‘spare us the further details’. On another occasion, while struggling to choose a suitable essay topic from the wealth of material offered by twelfth-century Ireland, I made the mistake of telling one of the leading experts in the field, Professor J.F. Lydon, that I found the whole thing rather dull. The resulting explosion could have shattered windows as far away as the Pav.

The extramural part of our education involved nursing cups of coffee and talking. This kind of thing tended to be conducted in the café of the Kilkenny Shop on Nassau Street, with its fine view of College Park. Celia West, Michael Buttanshaw, David Hughes, John Wilson, Mandy Daly, Patricia Quinn, Catherine Stokes, Louise Broderick, Ann-Marie Harty, Mary Devally and many more formed what was quite a largesalon.

Given that students are supposed to eat anything you care to put before them, it’s a measure of the horrors of college food in those days that we had a Students’ Union boycott of the Dining Hall and the Buttery shortly after I enrolled. As soon as we had got through Junior Fresh, we spent as little time as possible in the Buttery, ‘the orange painted hell’ asPiranhacalled it. It did, however, have two attractions. One was the Manhattans made by the lugubrious barman, Matt, who looked as if he had been painted by El Greco. The other was the chocolate biscuit cake, which was produced – and consumed – by the ton daily.

Towards the end of my time in Trinity, I became part of a kind of cooking co-operative, with Clive Lee, Dick Flood and a few other medical students. The idea was that we would take it in turns to feed each other in rooms, using two gas rings and such culinary skill as we could muster. My dish was a Hibernian sort of spaghetti bolognese; Dick’s was T-bone steaks. Clive stuck doggedly with his own invention, curried Knorr minestrone soup, which was much better than it sounds. On one of the few occasions when a bottle of wine (Vin de Table de Plonk) was produced, and set in front of the gas fire to become – ahem –chambré, it curdled. I have never seen such a thing, before or since.

We historians were amongst the last undergraduates to sit, as a matter of course, September exams. This relic of a more gracious age was fraught with one major potential problem: if you went down, you had to repeat the whole year. I panicked the night before my British medieval exam and went to bed in the hope that I would wake refreshed and clear-headed. Not so but somehow I managed to pass.

The following year, some of us started to conduct tours for visitors, with the blessing of the Senior Dean, J.V. Luce, who drawled his approval in that detached and sleepy voice of his. He even went so far as to say that college would not take so much as a tithe from our takings; we could keep the loot.

Pausing in mid-tour one day in the Museum Building, I pointed out the memorial plaque to Edward Cecil Guinness, first Earl of Iveagh, a benefactor of the college whom, we hazily understood, might have something to do with the free Guinness on Commons.

A gum-chewing American tourist asked suddenly, ‘Was he a Jew?’

‘No,’ I said, ‘I think he was an Anglican.’

‘So,’ said the tourist, ‘who was the Tullamore Jew, then?’

Tourists would often ask if the busts lining both sides of the Long Room were of graduates ‘of this school?’

‘No,’ we would reply, ‘Socrates was a bit early for Trinity …’

I wasted a great deal of time on the Hist and I’m not sure why. I was a poor-to-middling debater and the hard core – I rose to the dizzy heights of being censor and secretary – were obsessed with what one of them, during Private Business, described as ‘this society, which is greater than all of us’. It was also a hotbed of skulduggery, intrigue and bitchiness. As an antidote to all the law students at the Hist, I spent more and more time with people from the ‘science end’, especially medics. The Hist folk tended to frequent The Stag’s Head, while the scientists and nascent doctors favoured the Lincoln, with itsDublin Opinioncartoons, sticky carpet and outstandingly tolerant barman, Pat Healy, who later went on to have The Blue Light in the foothills of the Dublin mountains.

During the approach to my finals I decided to defer my departure from Trinity by the simple expedient of trying for teaching and the H.Dip.Ed., a course that, with very few exceptions, was taught by eccentrics, incompetents and the bone idle. In some cases, all three.

I found myself teaching in the mornings at St Columba’s in Rathfarnham, and sleeping quietly in the Edmund Burke Theatre in the afternoons. When we sat our exams at the end of the course we were astonished at how little of any value we had learned. And when, during our first paper, a member of the department arrived breathless in the Exam Hall to tell us that, ‘in question 3b, the word “aprents” should be “parents”’, the Revd Matthew Byrne, chaplain of King’s Hospital, exclaimed loudly, ‘Oh, that’s such a shame! I’ve just written three pages on aprents.’

The strangest part of the H.Dip.Ed. was that I got a first in statistics. I’m still convinced that this was some kind of computer error. I continued to teach at St Columba’s but decided that I would pursue a part-time M.Litt. Of course, it was not a foregone conclusion that I would be accepted for postgraduate work and I am eternally grateful to the School of Modern History that they decided to give me the benefit of the doubt.

The M.Litt. fizzled out over the next year or so (I blame the paucity of original source material, which is always a safe bet) and my name disappeared from the books of Trinity College Dublin. But I don’t think I ever really left.

Tom Doorley(TCD1977–83; History) did the H.Dip.Ed. (1982) while teaching at St Columba’s College, Rathfarnham, and stayed there until 1985. Since then he has worked for theIrish Independent,The Sunday Tribune,The Sunday Business PostandThe Irish Times. He is now food and wine critic and general columnist with theIrish Daily Mail. He has worked in advertising and, asPRadviser to Durex in the 1990s, saw condoms become legal in Ireland. Thanks to his work in television and radio he has become whatThe Cork Examineronce described as ‘a minor celebrity’ and divides his time between rural Munster and Dublin. He is married to Johann McKeever and has three daughters.

A DIFFERENT PLACE

Aine Lawlor

It wasn’ta place I’d ever been until I sat the Matric. For years, it was the mystery behind the walls I’d walk past or glimpse from the top of a passing bus. The home of the Book of Kells, and the otherwise unknown. Nor was Trinity a place that girls from my convent school tended to go. There was no longer a ban on Catholics, but still the decision to go there brought the whiff of difference in a world where my father didn’t quite get why a daughter would go to college instead of getting a job.

So, naturally, Trinity was irresistible to me.

For the first few weeks and months I felt hopelessly out of my depth; navigating the new Arts Block, getting used to and then loving the pall of smoke that hung over the Buttery, Matt throwing his eyes up to heaven behind the bar, Janet clearing the tables and proclaiming her views on the news of the day or the carry-on of the students around her. After a time you got to know her crooked smile, and the pleasure she took in friendship.

And the surprise at finding out how little I knew about the real world, the world outside of books – the markers of class that I hadn’t learned to read, but that made such a difference. We’d grown up in Fianna Fáil land – a world where our parents worshipped de Valera and the Pope; both their pictures up on the kitchen wall. It was a world I’d been dying to escape from, but I didn’t realize what a klutz I’d feel amongst those reared to take privilege and choices for granted.

On the other hand, there was the joy of meeting gay people, straight people, Northerners from both sides of the divide, black people, brown people and country people. Suddenly ‘diversity’ was lots of people I knew and called friends and not just a word in the worthy novels I tended to read back then.

In school, May was the month of Mary. In Trinity, May was the month of exams, yes, but also of the Trinity Ball, of sitting on a windowsill in Botany Bay on a sunny evening, or watching a cricket match while having a drink down at the Pav, as the buses roared past outside. During my first few years, the world beyond the walls disappeared, obliterated by the distractions of this new world: Players, the debates in the Phil and the Hist, and all the goings-on besides – the Cumann Gaelach, O’Neill’s on a Friday night, the Palace, the Bailey and warm chocolate doughnuts in Bewley’s. Dublin was dowdier then, the recession biting. But there was also a sense of a new Ireland rising:U2and The Boomtown Rats; the Sheridan brothers and John Stephenson in the Project; gay rights and feminism; Tony Gregory. Dowdy yet exciting.

I got a job in the Students’ Union shop, one of the few places in the country you could buy condoms over the counter. I remember there were four brands on sale, the cheapest, Black Shadow, at 70p. Those were popular with shy young men and furtive middle-aged ones. The older men I usually didn’t like, my convent sensibilities put off by their spending less than a pound on the nasty black ones instead of £2.50 for the dozen of Featherlight. The young guys were sweet, in and out a few times to drum up their courage, and always asking for a Mars bar first.

Big days came and went on the Dining Hall steps. We occupied buildings around college in various campaigns, heady with indignation at the prices and standards of catering, or library opening hours. Once there was a warrant out for my arrest over an illegal occupation. I came home that night, I think it was April or May of 1980, expecting that the next day would see my arrest as a lowly member of the Students’ Union executive. That was to reckon without my mother’s swift intervention. The next day I was on a plane to exile with my aunt in Germany, while my father was left with the job of purging my contempt of the court injunction. So much for any attempt to be radical on my part.

The harsher realities of politics and life outside Trinity in the early eighties soon began to have an impact. I remember Bernadette Devlin speaking to a huge crowd in Front Square during the hunger strikes, the black flags that appeared on the way into college, the way the city resembled those news clips from Belfast on the way home at night – gardaí in riot gear jumping out of vans, buses on fire, O’Connell Street in chaos. Waiting for the news each morning to find out whether Bobby Sands had died, and whether anyone else had paid the price of a life or a limb in those bitterly sectarian days that intruded even into a Trinity student’s bubble.

It was hard to avoid politics. Even during exam time, trying madly to cram three terms’ work into three weeks, there was the distraction of the loudhailers on the election vans passing down Nassau Street calling on us all to arise and follow Charlie. You were with him and his Ireland, or against him, and Trinity, for all its faults, was an important oasis where you could see lots of different kinds of Irish people with different kinds of beliefs.The Irish Timesbecame more important for morning coffee than a chocolate doughnut as it chronicled the grotesque and the unbelievable, the economic crisis, the sectarian and culture wars. Slowly, I was learning to see my country with adult eyes. My childhood was a world of great security and sunshine, with a sense of community I’d only truly value later on in life. But back then I had stood against its unquestioning loyalties, and its questionable ethics.

Towards the end arose the question of what to do and where to go. Somehow I decided that being president of the Students’ Union was the next best step. And, despite the forty-seven engineers who also decided to run for president that year, and in no small thanks to my election agent, law student Ger Scully, and the barrel of beer I promised the engineers for their second preferences, I managed to get elected.

The bonus of student office was a year in rooms, a summer of falling in love while they filmedEducating Ritaoutside my bedroom window, artificial snow falling under an August sky. With term time came the chance to learn how Trinity worked behind the scenes, a glimpse of its political mechanisms, but most of all the pleasure of getting to know the eclectic groups of academics and staff who kept it all going. What had seemed distant and formal and archaic before became personal and funny and humane. I discovered how often the staff were really on the students’ side. Before, I’d only known the academics who taught me or those who’d hung around the Buttery or the debating and meeting rooms. But now I also had the chance to come to know those involved in running departments or sitting on committees. The Students’ Union fought the cuts and went on marches but student protest mattered less to me now; what was going on in the country became a greater preoccupation. The internal machinations of student politics quickly seemed pointless but that year of living in college was one of my highlights.

And then it was all over, and time to head back outside Front Gate. I took with me what mattered most, a relationship with Ian Wilson, who married me and is with me still, the friends who are still friends, and a belief in curiosity and diversity that I try to hold on to.

There’s less of a divide between Trinity and the Ireland outside its gates these days, which is as it should be. Both the country and the institution needed to change. But there was a time when, to me, Trinity’s singularity represented something important, it was a place in which there were choices about being Irish. It was more than an academic institution. It was a place that welcomed all kinds of different people whose reality was denied in the Ireland of my childhood. And that’s what mattered most.

Aine Lawlor(TCD1978–82; English and Irish) was president of the Students’ Union 1982–3. An Irish radio and television broadcaster, she co-hosts theMorning Irelandradio show onRTÉRadio 1. She lives in Dublin with her husband Ian Wilson, a producer inRTÉ2fm, and her four children. Her interests include gardening and growing and cooking her own food. She was presented with the Trinity College Alumni Award in 2008. Other awards includePPINews Broadcaster of the Year 2012 andTatlerWoman in Media of the Year 2012.

NORTHERNERS, POETS AND NOT BEING BEATEN BY THE RECESSION

Hugo MacNeill

I supposeone should be careful not to over-romanticize the past. I don’t think my memory is too selective but when I look back on my Trinity days, my sense is of a magical time.

And yet the economic backdrop was dire. It is interesting to compare the situation of the early 1980s with that of today. The unemployment rate was 20 per cent and most of us emigrated on graduation. There was very little entrepreneurship. Those who stayed went mainly into the ‘safe’ professions. Start your own business? What if it went bust? What would your parents say to the neighbours?

I suppose we thought it would get better, or that we would cope with it one way or another. A recentIrish Timesseries on young people showed an overwhelming desire not to get sucked into anger and frustration at the current crisis but just to get on with things. Maybe that’s one of the best things about being a student; you put things in a wider context. And in spite of the terrible state of the early 1980s, we did see a subsequent economic transformation with a profound and lasting change in terms of entrepreneurship. People who set up companies that failed set up others that worked. Unemployment went down and just about everyone I knew who wanted to come home, did come home. Myself included. Will that be the experience of today’s Trinity students?

My Trinity rugby days followed the success of John Robbie’s Leinster champions of 1976 and came before Trinity challenged again in the mid 1980s; in fact, during my four seasons we did not win a single match in the Leinster Senior Cup. Did I really enjoy it? After all, I had just come from the fanatical atmosphere of a Blackrock College Schools’ Cup-winning team. Adversity bred great strength and friendship. We were all just out of school, without worries about jobs or families. Just sport, studies, meeting people and having fun. New friends and teammates were drawn from places that had until recently been our deadliest rivals: Terenure, St Mary’s, Clongowes and De La Salle. Years later, I was privileged to tour with the British and Irish Lions and I had the same experience on a wider scale, getting to know and play with Scots, Welsh and English players, former adversaries from Twickenham, Murrayfield and Cardiff.

The day after a match was always special, a sensation of pressure released even if the mission had not been accomplished. Sitting in the Pavilion bar with friends, teammates and supporters, the prevailing feeling was not one of ecstatic celebration but just real satisfaction. There are few feelings comparable to being with friends and teammates the day after a victory. Subsequently, in the Irish teams we always made a point of meeting the next day with friends, wives and girlfriends before parting for home in various different directions. I had the shortest trip of all – the walk down from the Shelbourne hotel and in through the Lincoln Gate. You can’t be a student and an international these days. I would have hated to have had to make a choice.

Academic and sporting life went hand in hand. Thanks to teachers like Dermot McAleese, Sean Barrett and John O’Hagan in the Department of Economics, I was fortunate enough to be elected a Foundation Scholar. With it came rooms, fees and Commons in the evening. The real benefit was that it enabled me to spend a year studying Anglo-Irish literature, just for the pure enjoyment of learning. Being introduced to James Joyce by the enthusiastic David Norris was a wonderful experience. I recall the quiet precision and dry Ulster humour of Terence Browne. And then there was Brendan Kennelly.

Spending time in his poetry classes and getting to know Brendan as a friend was one of the real highlights of my time in Trinity. Our first meeting was memorable. Having decided on Anglo-Irish literature, Professor Trevor West advised that I had to meet Brendan to explain that this was not an excuse to stay on playing rugby. Trevor was the most complete university person I have ever met and a special friend. He touched so many aspects of university and wider Irish life – scholar, sportsman, gifted teacher, university senator and peacemaker in Northern Ireland.

We had a great night in O’Neill’s of Suffolk Street and then went back to Brendan’s rooms. West and Kennelly started arguing about who was the better sportsman. This could not be left to theoretical speculation but had to be verified empirically. So off across Front Square to College Park they marched at half past two in the morning. I was the starter for the 400-metre chase between the Professor of Mathematics, senator and chairman ofDUCACin one lane, and the Professor of Anglo-Irish Literature in the next. Off they sprinted with West taking an early lead around the bend by the law library. The benefit of Kennelly’s Gaelic football youth kicked in and he took the lead down the back straight and towards the Pavilion. In a last desperate throw, West tried to take advantage of the gloom and the Cork mathematician bisected the bend towards the finish line. He didn’t make out the cricket net and flew into it at top speed as Kennelly came down the home straight, raising his arms, laughing all the way.

During the international rugby season, Brendan and I would meet on the Monday night following each game. You are quite insulated when you are playing, physically and in every other way. You are unaware of the wider context that makes those weekends so special. Hearing about Brendan’s adventures on a rugby weekend enhanced my own experience of playing for Ireland.

The team used to stay in the Shelbourne and Friday mornings were normally free. Even when I had left Trinity, I would often drop down to Brendan’s poetry class on the Friday before training. In 1985, I got Brendan two tickets before the Triple Crown and championship decider. On the Monday night, he was in good form but seemed a little awkward. The country had been celebrating for the previous two days. His mood seemed quiet. He finally confessed that he had headed out for the big day and stopped at a pub in Beggars Bush. He met a lovely English couple, on their first trip to Dublin but a little down because they could find no tickets. Brendan gave them his and then went and watched it onTV. He was worried that I would have minded. How could I?

In recent years, I have become involved with the National Institute for Intellectual Disabilities in Trinity where students do a two-year course and receive a Certificate of Contemporary Living. It is truly inspirational and one of the greatest initiatives I have seen in Trinity. Brendan captured its spirit perfectly when speaking on the Institute’s prize day. He thanked it for‘removing the mask of disability to reveal the extraordinary ability that lies beneath’.

Two other things made Trinity special for me. First was the stepping stone to Oxford and the second was the link with the North of Ireland. Trinity at the time was not very cosmopolitan. Students from the North, the Anglo-Irish tradition of the South and a few random overseas students was pretty much it. In 1981, Oxford made their first visit to Trinity for many years. As captain of Dublin University Football Club (DUFC), I waited in the Pavilion with other players and club officials for the coach to arrive via the Holyhead ferry, and the Oxford contingent eventually appeared in their dark-blue blazers. Over that weekend I got to know some of the most remarkable people I have ever met, many of whom became close friends and teammates.

At the time there was much debate in Ireland as to whether the Irish rugby team should tour the still-apartheid South Africa at the end of the season. It was my first season in international rugby. Despite his love of rugby, South Africa’s Chris Hugo-Hamman advised against playing South Africa as long as the apartheid regime was in operation. I subsequently chose not to go.

The North has always been important in my life. Some of my earliest memories are of the annual family holiday to the seaside at Bettystown, which always included a day trip to Newry where we could buy ‘English’ sweets. At Blackrock we had playedRBAI, Campbell and Methody. That was my first real experience of going north. It used often be said that the great thing about rugby in Ireland was that players could come together from North and South and ‘the Troubles’ were never discussed. I always thought that was fine as far as it went. But if people who knew and respected each other could not try to understand the other’s tradition, how could we expect kids from polarized ghettos to do so? We did talk about ‘the Troubles’, and that bred mutual respect.

TheIRAceasefire broke down when it bombed Canary Wharf in London in 1996. Trevor Ringland and I organized a ‘Peace Rugby International’ where the Barbarians brought many of the world’s leading players to play the Irish team. It was meant as a statement against theIRAand other terrorist violence. Large elements of ‘middle Ireland’ were speaking out against this violence for the first time. It was quickly organized with inspirational help from many people and was probably the most emotional of many days at Lansdowne Road. The guests of honour were children touched directly by violence; a young Protestant boy who lost both parents and a brother in the Shankill Road chip-shop bombing; a young Catholic whose brother died in a reprisal shooting in Greysteel; an English boy whose best friend was killed in theIRAbombing of Warrington.