Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

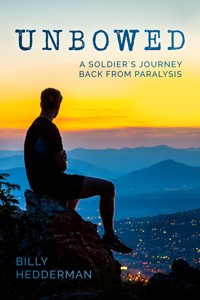

Unbowed: A Soldier's Journey Back from Paralysis is the story of a dramatic recovery from diagnosed quadriplegia to a level of functionality rarely seen. Billy Hedderman was body boarding on the Sunshine Coast, Australia on New Year's Eve 2014, when a wave dumped him into the sand. He broke his neck, back and suffered immediate spinal cord damage, paralysing him from the neck down. Lucky not to drown, Billy was rushed to Queensland's premier spinal injuries unit where he began the difficult road to recovery. Yet incredibly within seven months of his injury, the incomplete quadriplegic ran a 10 km race in Brisbane in under one hour. Billy details how his previous life experience – such as service in the elite Special Forces unit Army Ranger Wing, and the death of his two close friends – have assisted in his mental toughness to prevail against all expectations. The book provides insight into Irish Special Forces from a recent serving tactical commander. Billy is currently a serving Captain in the Australian Infantry.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 444

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.twitter.com/IrishPublisher

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Billy Hedderman, 2018

ISBN: 978 1 78117 593 4

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 594 1

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 695 8

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Abbreviations

2IC – Second-in-Command

6 RAR – 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment

ADF – Australian Defence Force

APC –Armoured Personnel Carrier

ARW –Army Ranger Wing

Bn –Battalion

CAO –Central Applications Office

CCS –Central Cord Syndrome

CO –Commanding Officer

CP –Command Post

DF –Defence Forces

DS –Directing Staff

HQ –Headquarters

HVT –High Value Target

LFTT –Live Fire Tactical Training course

MTC –Multi-Training Centre

NCO –Non-Commissioned Officer

NGO –Non-Governmental Organisation

OC –Officer Commanding

OIC –Officer in Charge

OT –Occupational Therapy

P&O –Prosthetics and Orthotics

PA –Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane

PESA –Physical Employment Standard Assessment

PT –Physical Training

QRF –Quick Reaction Force

Reo –Reinforcement cycle

RSM –Regimental Sergeant Major

RTU –Return to Unit

RV –Rendezvous

SCI –Spinal Cord Injury

SERE –Survival, Escape and evasion, Resistance to interrogation and Extraction

SF –Special Forces

SIU –Spinal Injury Unit

SOTU-M –Special Operations Task Unit – Maritime

UL –University of Limerick

Prologue : ‘You Wrote a Book?’

I woke to the sight of a hospital ceiling. For that first blissful second, I forgot that I was paralysed. While attempting to distract my brain from the ever-present pain, I concentrated on each item I could see within my motionless field of view, staring intensely at each minor stain on every grey ceiling square. I was then brought to life as my wife, Rita, pressed down on the bed remote control to lift the top half of the bed, raising me semi-upright, Frankenstein-style. I fixed my gaze on the printed poem hanging from the bottom of the TV screen and read it again.

Invictus – William Ernest Henley

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be,

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance,

I have not winced nor cried aloud,

Under the bludgeonings of chance,

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears,

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years,

Finds, and shall find me, unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

I reminded myself of this message every day. I may not have been able to move but I was still in control of my thoughts. I read it when in pain. I read it when I felt low. I read it when I was bored.

***

Throughout the four months I spent in hospital after my accident, I received numerous good wishes in the form of letters from extended family, gifts from friends and texts from many connections of all types. I was also sent video messages by Irish Army mates, pictures from friends all over the world and drawings from young relations. It was humbling to feel so cared for and to know that people were wishing the best for me. It was also incredibly motivating.

On top of this I was contacted by a number of people I didn’t even know. I received an email from Nathan Kirwan, a fellow Corkman, who described his own fight against paralysis and wished me well. Afterwards, I followed his progress in his robotic exoskeleton, and his determination and positive attitude were fantastic to see. I also received a video message from Mark Pollock wishing me well for my recovery. I had heard of Mark, racing blind across the Pole, then tragically becoming paraplegic through an accident, yet still managing to maintain an incredible outlook on life. I had heard of his organisation, The Mark Pollock Trust, and his charity run called Run in the Dark. In fact, my mother had participated in one of these runs, although I have to admit that I didn’t know exactly what the Trust did at the time. It was quite exciting and humbling to watch his video message, where he spoke directly to me. Overall, I was really taken aback by the number of good wishes I received.

As I started to recover I decided that I wanted to return some form of thank you to everyone that I could. I apologise now to anyone I didn’t get back to! I really wanted to try to explain to everybody how much their support helped. ‘If there’s one person that I know can pull through this, it’s you Bill’, was the type of message I received. It probably only took a few minutes for people to write these messages, but every one of them gave me that extra tiny piece of affirmation not to give in. I needed to let people know that their kind words really helped.

When in hospital, I had required a splint to even hold a pencil. However, as my condition slightly improved, I eventually reached a stage where I was able to hold one without a splint and I began to attend writing classes as part of my occupational therapy (OT). It was incredibly tedious and, for some reason, much more depressing than most of my other therapies. I think it was probably because the page didn’t lie: I could see how poor my writing was. If I could not even write, how would I ever get back to work?

Patience and persistence pay off, though, and in the end, I improvised in order to overcome this difficulty. This involved routing my pencil through my index and middle finger – rather than between my thumb and forefinger – as I didn’t (and still don’t) have the pincer dexterity to write shapes accurately through the traditional holding position. A few weeks post-discharge from hospital, I sat down in my office at home and pulled out an A4 notebook. I wedged the pencil in, held the page as steadily as I could, and leant my head down close to my hand. The first letter I replied to had been sent by a large group of Rita’s friends who had been superb to us both. They even pooled money together to buy me an iPad loaded with applications on which to conduct hand and finger therapy. I thought it would be best to write my reply by hand to those who had done so much for me. It was excellent practice for me, while also showing the recipients how well I was recovering. I wrote a three-page letter of thanks and praise to all those wonderful and thoughtful people. Following this, I wrote back to many more well-wishers. I actually enjoyed reflecting on how each one had assisted me and, honestly, I just wanted them to know that it had helped.

As well as learning to write again, I also had to relearn typing. After my release from hospital, I began intensive therapies at home. Physio and OT became the daily grind. In one of my first home sessions, the occupational therapist asked me to select a book from my collection and bring it to the laptop. We opened Brian O’Driscoll’s autobiography together and read the first paragraph. She asked me to type it out in a Word document, so I did, as she stared at her watch. Again. And again. And again. With my fingers hovering in place over the keyboard, I had to concentrate on selecting the appropriate finger for the correct letter, and then focus on pushing downward with the finger, as opposed to the hand. A word was annoying, a sentence was frustrating and a paragraph was hell. That evening I was given ‘lines’ to type as part of my ‘homework’. It was exceptionally boring.

After only a few days of typing practice I had had enough of lines. Maybe I can incorporate the typing practice, my story of resilience and my thanks into something else, I thought. Quite soon after my accident, my brother and I had decided to start a daily log. Every night before my family left me motionless in my darkened hospital room, I asked whoever was present to log all the visitors and to transcribe the positive and negative feelings I’d had that day into a little notebook. Sometimes I felt terrible all day, but I always had to find a positive to add to our notebook before another quadriplegic day came to a close. Always find the good in any day. It was an excellent tool that we employed throughout my time in hospital. I kept the notebook and still like to read over it from time to time. When I got bored with typing lines it became a good place to start from. Hey, instead of just writing lines from someone else’s story, why don’t I start writing my own, adding to the notebook we wrote in hospital? I asked myself.

I had been told that writing and logging events throughout my recovery would be good for my mental state, so, at first, I justified my self-indulgence of writing what soon developed into this autobiographical book by convincing myself that it was a form of hand therapy and mental well-being. But then I realised that rather than just writing for myself, I wanted to spread my story in order to let others know that, in certain cases, it is possible to recover some way from paralysis.

Although the first drafts were not particularly eloquent, I persevered. Parts of this book were originally typed with single-finger punches from partially paralysed hands, as I furiously concentrated on spelling out each word. But in the end I had a complete manuscript and that is what you are reading now. The aim of this book is to outline to the reader that high levels of resilience and self-belief helped me through difficult times, and that they can do the same for you.

1 Relax, Bill

Brisbane, Australia – December 2014

It was late December 2014, and Rita and I had been living in Australia for almost three months. What family and friends back in Ireland had touted as being the biggest move of our lives seemed to be working out quite well. The weather and lifestyle were fantastic. We were living in a beautiful house on the northwest side of Brisbane, only a two-minute drive to the army base where I worked. Our estate was filled with other Australian Defence Force (ADF) families, each with a house as fine as ours. It was a clichéd existence, with everyone barbecuing and walking their dogs around the nearby pond, their kids playing outside in what seemed like eternal sunshine.

Rita and I tried to get out as much as possible in Oz, to embrace the new country. After all, having moved to the far side of the world, we had to live our lives fully; otherwise what was the point in moving? Naturally, part of this lifestyle was going to the beach, which we did regularly. After spending our first Christmas away from home with some of our newly acquired Oz-based friends, we decided to travel up the coast to Caloundra on New Years’ Eve for a beach day. Just Rita, our dog, Ozzie, and me.

When I’m on leave I tend to move slowly at times, and this was the case as we prepared for the trip to Caloundra. In contrast, Rita rushed around the house, getting ready, packing towels, slicing and dicing lunch for us, and, of course, continuously interrupting the dog and me from our TV viewing – the events of Mythbusters were not high on her list of priorities. I was ordered a number of times to get out of my pyjama pants and assist with the preparations. I looked to Ozzie for some sympathy but he glanced away, leaving me on my own. He is clever, in that he never takes sides. I eventually pulled myself away from the couch and began the process of packing for the beach. I was in slow motion while Rita was in fast forward.

As soon as we stepped outside to pack up our newly purchased Toyota Yaris my mood changed. Just another absolutely amazing day in Brisbane. I truly believe that weather can affect your mood. In this case it undoubtedly had a positive effect, as I loaded an Esky (cooler box), a blanket and, of course, our little VIP, Ozzie, the Scottie from Ireland, into the back seat. Oh, almost forgot the body board and rash vest, I thought; they had been staring at me from the garage.

Shades on, GPS on, Classic 90s dance tunes on; we were good to go. Soon we were backing out of the driveway and on our way. We weren’t long into the drive when Rita reached over and turned the music down, much to my dismay. I worried about what was coming. We had been a little off with each other over the previous few days, as we had been arguing over our finances and how we were managing our accounts. So it was to my surprise that we ended up having a long, lovely discussion en route to Caloundra, agreeing not to worry about the small things and to just enjoy ourselves. We decided that the New Year was going to bring us happiness, and that while saving was important, living for now was more so. I glanced back at Ozzie, but he just raised his eyebrows. I have to say, I felt good after our family team talk.

On our arrival at Kings Beach I conducted my usual army-style unloading drills. Eventually, we found a spot that satisfied Rita’s requirement to be close to the water and the dog’s requirement for constant supervision – territorial Scotties can be quite the handful when other dogs decide to invade. We laid out our blanket on a grass patch just off the beach and plonked ourselves down.

Man, this is awesome, I thought. I am one of those people who has to get into the sea as soon as possible upon arrival at the beach, so I grabbed my vest and board and shuffled towards the water. Stopping short, I gazed across the surf. I picked a spot that had a few, but not too many, boarders around. I was nervous about potentially running over some child in the water, so I didn’t want to squeeze in where most of the other boarders were located. As I waded in, I found that the waves were stronger than they looked. I noted the rocky wall 100m to my right as I leaned my shoulder into crashing and quite fast waves. Once beyond the break, I set up in an area where other body-boarders were riding the waves. After a while, I caught a few waves, riding them all the way to the shoreline. Each time I caught one I felt a little more confident. I started adding turns into my glides.

I had notions of starting surfing, but for now I was stuck with the smaller board. It was good, easy fun. As I zipped along the crest of the wave, the spray kicked up into my eyes and stung. On reaching the shoreline, I would stand up, wipe my face, fix my shorts and then traipse back out again. It was a nice activity but not something I was overly fond of. There was a small buzz in riding the wave, but it took a lot of work to get back out through the waves to go again. After thirty minutes, I stumbled from the water as waves struck my back, pushing me out, telling me I wasn’t wanted there any more.

As part of our ‘embracing life’ policy, Rita had come up with a rule that we had to say yes to anything we were invited to. I liked it. It forced us to get to know people and make new friends. We had planned to meet some of our new friends that evening in Brisbane to ring in the New Year, so after lunch and a dog walk, we began to plan the journey home. Before we left, however, I told Rita that I wanted to go in for one more dip. I was so genuinely happy with life that I felt I had to share it with my family in Ireland, and maybe rub it in a little! So I made a quick video, showing off how great life was at the beach, and posted it off to my family on our WhatsApp group before heading down to the water.

Due to the beach-loving culture, many people jump into the Australian surf with no prior exposure to or knowledge of what they are doing. However, I’d been body-boarding plenty of times before and surfing a few times in Ireland; in fact, I’d had a surfing lesson only six months earlier. Worse still, I had YouTubed ‘body-boarding techniques’ to ensure I was doing it correctly. I’ve always been that way. I like doing exciting or ‘extreme’ things but I never take safety for granted. It’s like risk mitigation. Yes, do something extreme, but do it the correct way. I’m not sure from where I picked up this value. Maybe it’s a military thing. Rita calls it my ‘inner old man’.

Anyway, this time I would take the board out to about four or five feet of water, then turn it inwards. I would watch over my shoulder, waiting for a wave to crest and then extend the board out. Then I would paddle and kick until the point where I could feel the wave lift both the board and me, speeding me towards the beach and flattening out as I neared the shoreline. A few times as I waited for it, the wave would turn a little too early and either I’d get the white horses running towards me, or worse, it would turn just on top of me, in which case I would get a little bit of a trashing. Not ideal, but I’d give myself a quick little debrief then try again.

I contemplated heading back in after about ten minutes, but I couldn’t leave on anything other than a good surf. My last one couldn’t be a wipe-out. So, I set up for a wave. As it came closer, I could feel that it was going to be bigger and stronger than those that had preceded it. The waves on Kings Beach can be powerful and have a very strong pull back as they gather volume. I turned and faced inwards towards the shore as this one came close. The wave crested just behind me and I could feel it pulling me up and backwards. My hips raised up higher than my core and I knew then that I was going to get wiped out. The initial pull back seemed to take an eternity, as if the wave itself was suspending time, but after that everything else happened so quickly, the speed and power catching me unawares. The top of the board caught in the water below and the board flipped out from under me so that I was propelled, forward and downward, through the violent momentum of the wave. I felt a strong and hard thud as I hit the top of my head off the sand, while my torso was being pushed forward over my head. Basically my body was caught in something like a very ungraceful and powerful forward roll with a sharp neck inversion. I immediately felt heavily dazed.

I have been concussed a number of times, but an underwater concussion is a surreal experience. I can vividly recall what I could see and how the sand was moving forward and back below me, while waves continued to ride over my head. Although my mind was hazy, I knew I needed to stand. When nothing happened, I didn’t panic straightaway. Even in my haze, I thought I would shake it off within a few seconds and stand up. I continued staring at the movement of the sand. In and out. In and out. Still dazed, I was beginning to grow confused as to why I wasn’t standing up. My chest quickly began to remind me that I was underwater. It started sucking in and out. I began panicking. I was drowning.

Stand up, Billy. Roll over, Bill. Do something!

From time to time, I replay these seconds in my mind. In fact, writing about it now brings it close. After what seemed like a long time, I heard a faint murmuring voice: ‘You okay … hey, you all right?’

I could tell someone was nearby. I was finding it difficult to control my chest. Suddenly my head was slightly out of the water. I spluttered and took in a shallow and broken breath. Water came in over my face. I was disorientated and in complete shock. My breathing was extremely shallow and my chest, which felt incredibly tight, was exploding in and out. What the hell is going on?

One of the young guys who had been body-boarding around me earlier was talking to me. He was around fifteen or so. He wasn’t very strong as he was holding me funny and the shallow waves kept coming over my face. I was struggling to breathe with water rushing over my mouth. I heard other voices and suddenly I realised I was moving out of the water. I remember thinking: Hey guys, if you’re going to carry me out of the water organise yourselves a bit more, you’re not holding me properly, who owns this arm hanging down here … wait, what the hell … that’s my arm! Oh my God, what’s going on?

They laid me down on my side and I heard someone say something about ‘C spine’. I tried whispering it in a weak attempt to agree with them. I recalled my army medical training, which stated that if there is any chance of a spinal injury, during the immediate actions one should fix the head and neck in a neutral position. I was still attempting to catch my breath, desperately searching for a moment’s relief.

I felt so messed up that I thought I might be dying. I was genuinely worried I was going to drift off. Thankfully, after a few seconds I was able to collect my thoughts. I gave myself a little talking to and started going through my A, B, Cs. Okay, airway: well, I can whisper. Breathing: shallow but okay. Circulation: no cuts that I know of and the heart is still just about pumping. Hey, I’m okay. Now relax, Bill, settle down, you’re not going to die.

2 Leadership 101

Kildare, Ireland – October 2001

Unlike in many of the classic rags-to-riches biographies that I have enjoyed reading, there is no tale of woe from my upbringing. My parents made sure we were never deprived. We were not well-off, but we were also not poor. I am the second eldest of four children, two girls and two boys. We kids fought a lot growing up, as tends to be the case when siblings are close in age. My mam stayed at home while my dad worked as a car salesman. We lived in a housing estate in Glanmire, County Cork, until I was eight years old, and then moved to a detached bungalow in the country, 3 miles from the village of Watergrasshill.

My mam is extremely knowledgeable, caring and very passionate, which is where I get my argumentative streak, I think. Both she and my dad were very involved in sport, which was bred into their children. My mam used to drive us to training or matches all over Cork, always supporting us in any endeavour and telling us that we had done well. She also pretty much ran the household, was an amazing cook and kept us from killing each other. We were exceptionally lucky to have been raised by her; however, I probably didn’t appreciate it enough during my immature teenage years.

My younger brother, Simon, and I looked up to my father so much growing up. Any praise or criticism from him was taken very seriously. We had heard so many stories about his skill and speed as a Gaelic footballer, how he captained the Cork minor team, and played senior football from the age of sixteen. As our parents were relatively young when we were growing up, we watched my dad in action many times playing soccer and Gaelic football with local teams. He was super aggressive, strong and skilful. This was most likely one of the main reasons why we were both so competitive and tenacious.

My parents always prioritised their children, never once showing any favouritism, and they backed us all, no matter what. They challenged us hard and always seemed to be in agreement when it came to us. They made us study, they encouraged us in everything, from art, sport and drama to part-time jobs, and were there to watch, critique and praise after each activity.

However, I still went through a classic case of teenage identity crisis. I was a very different person depending on the group I was with. At home, I could be belligerent to my mother and on occasions actively sought out fights with my siblings. In school I clowned around a bit in my own class, letting people know that I wasn’t a ‘swot’, but with those outside of my direct peer group (and in particular with any girls on a higher coolness rating) I would be extremely quiet. In fact, I used to regularly blush when talking or awkwardly hanging out with girlfriends and their friends. But even just a few hours after my shy interactions, I would go out to play rugby with Sundays Well, a team I started playing with when I was nine years old, where I was cocky, bossy and thought I was the best out-half in Cork for my age.

I was always extremely competitive. No matter what the activity, I had to try as hard as possible to win. I was particularly focused when playing organised sport. I just hated losing at anything. I would spend hours on end outside practising a certain aspect of a skill: smashing a football off the garage door over and over, curling it around the exterior corner of our house as I concentrated on hitting the top corner lip as often as possible. We regularly organised mammoth games of football/soccer/rugby/hurling in the back garden with the entire family and neighbours that would last for hours as my brother and I dreamt of scoring the last-minute goal for our team. Simon and I loved beating each other in any challenge, although I had an unfair advantage of four years over him. We competed in literally everything. We would devise silly games to see who could win. ‘Right, you have to hit the wall below the kitchen window without the sliothar hitting the ground first.’ Not surprisingly, this led to a substantial number of broken windows. One window was broken so many times that my parents decided to change it to Perspex!

***

What type of career suits a super competitive, team sports-playing teenager? The army, of course. It came as no surprise that both my parents backed me when I chose to conduct an army officer cadetship straight out of school. They may even have been more confident about my ability to adapt to the military than I was. They were proud of me, if maybe a little nervous, which in turn gave me confidence.

After saying my goodbyes to my mam and siblings very early on 1 October 2001, I hopped into the car with my dad, wearing my finest Dunnes Stores suit (my only suit) and off we headed to the Curragh Camp in County Kildare, where I was to begin my officer training with the Irish Army. About thirty minutes into the journey, the talk died down and I fell asleep. Without the motorways in those days, the trip took approximately three hours. The 9/11 attacks just weeks previously had left a lot of people profoundly worried, even in Ireland, and lots of friends and family thought it was not a good time to join the military. But it didn’t affect my thinking in any way. To this day my dad still can’t fathom how I could sleep. He tells me of how he looked over at me snoozing and said to himself, ‘Does this young fella have any clue what he’s getting himself into?’

Honestly, I didn’t, really. Although I had been a team captain or group leader on many occasions throughout my adolescence, this was something vastly different. I liked the idea of being in charge and making decisions, but I had little experience in true leadership and was probably lucky to have been selected to undergo army officer training. I may have had some of the raw materials (I felt I had plenty of exposure to leading teams in competitive environments), but I had a very limited understanding of the military and I had never been overly interested in becoming a soldier. While the army seemed kind of interesting, initially it was the prestige of being offered a cadetship that I liked the sound of. But once I was offered that cadetship, which was seen as an honour, that triggered my interest further, although I was quite nervous at the thought of leading soldiers. How was I going to do that when I couldn’t tell one end of a rifle from the other?

We exited towards the Curragh Camp. For anyone who has not experienced coming off the dual carriageway and heading towards the camp, it is quite the movie scene. The distinct rattle from vehicles shooting over a cattle grid signifies the start of a single straight road with nothing but vast open green plains either side that leads to the camp hidden in a mass of large trees almost a kilometre ahead. A water tower peers over the treeline in front, greeting all approaching from the civilian world beyond. A mini Mordor, if you will.

Since the foundation of the Irish Defence Forces, each cadet class has been numbered accordingly. Mine was the 78th Cadet Class. My dad left me at the cadets’ mess where we were told to fall in (whatever that was). I thought my dad was a bit emotional when I left him but he was trying hard not to show it, so I ignored it. We were marched to our lines (rooms) and I met the lads with whom I would be sharing a passage – a dorm-like area with individual rooms off a communal hallway and wash area. There were eight passages, each filled with eight young nervous wrecks. One naval service cadet in our passage would leave at Christmas to conduct his specific training, then our two air corps cadets would leave after seven months to learn how to fly. The other army guys in passage were all from Dublin or Kildare. The ‘Rebel’ in me didn’t like this set-up at all! I felt like the country mouse, just turned eighteen years old and stuck in with all these ‘Jackeens’.

I hated the first two days. I contemplated going home. It wasn’t anything in particular that triggered the thought, I just felt as if the hype of joining the army was now gone and had been replaced with a lonely existence in a dorm of strangers, a myriad of cleaning tasks and a realisation that this was actually what I had applied for. But I had never really given up on something just like that before. Even from an early age, I never quit anything easily. If I didn’t correctly execute whatever skill I was practising, I would continue until I got it right. I would stay long after everyone else had finished rugby training until I got my penalty kicking more accurate. No matter how badly any team I played with was being beaten, I absolutely refused to give up before the very final whistle and was furious with those who did.

I wasn’t keen to start giving up now, just because I was feeling sorry for myself. I rang home on my new mobile phone (I had refused to get one until then) and had a chat with my dad. He said that the family would totally support me no matter what I chose to do. Then, on day three, I got up and thought to myself, Right, stop your whinging and let’s do this. I have no idea why it clicked, but I never thought about quitting again, not once.

I buddied off with Cahill B, the guy in the room opposite me (there were two other Cahills, J and E). He had a broad Dublin accent, and was tall and jovial. He was a comic genius and kept passage morale high with his hilarious quips and impersonations. I started to get over the stupid issue I had that all these guys were from Dublin and soon we really began to enjoy each other’s company.

We were in a section together with a few other characters from the passage alongside us. A section is the smallest sub-unit grouping in the army, usually consisting of nine soldiers. We had an excellent mix of personalities and I thoroughly enjoyed it, probably due to my prior love of team environments growing up. We had an absolute ‘animal’ from Galway; in fact that became his nickname. John was our weapon in Section 1. We had two guys from Tipperary, both incredible rugby players. Denis was a prop forward who had previously served as a private in the 4th Infantry Battalion in Cork, and Colin was a stocky, Neil Back-type back row with a reputation of being one of the finest young rugby players in Munster. They were both super strong, which was of great assistance during our vast array of team physical activities.

Helen was a local army brat (military slang for someone who had a parent high up in the army and therefore got teased for perceived favouritism towards them), and although she was small and struggled at physical training (PT), she was quick-witted and well able to join in with the fun and the banter. Dave from Naas was in a room next to Cahill B and he was a dark horse. He was good at most things and cool as a breeze. He was passionate about only one thing: horses.

Mike from Finglas was in the room alongside me. I didn’t know what to make of him. He was quiet and had a thick Dublin accent. He was a little older than us and already had his master’s degree, never mind a bachelor’s, in economics! I thought this guy was in the wrong game, that he was too smart to be polishing taps and waxing floors with us idiots, as we were still working out right from left while marching.

After a short stint, we were told to change buddies and I ended up with Finglas Mike, while Dave took Cahill B. Mike and I got on quite well. He looked out for me and vice versa. I recall after one Battle PT session he couldn’t open his laces as his fingers were too cold, so I dived down and opened them up while under time pressure myself. On countless other occasions he looked after me. That was the nature of the buddy system. Simple. You were not joined at the hip, but assistance was there when you needed it. The buddy system was one of the first lessons we learned in the cadet school. Suddenly you were responsible for someone else. Before every inspection (of which there were many every day), a good buddy checked you. If your buddy had a pocket open during an inspection, it was your fault, and both would get punished. The technique was so simple but almost immediately taught us that selflessness was a key part of leadership.

The last member of our section, Mac, was to us what Murdock is to the A-team. Mac had accidentally blown himself up in a petrol fire about two months prior to enlistment, so his face, hands and hair were still a bit raw. The guy just loved everything exciting about the army. He hated running but he just couldn’t get enough of the shooting, blowing stuff up and generally playing soldier. The class voted him in charge of the cadet school air-rifle association, which was designed to assist those in need of further marksmanship training to practice in a simple shooting gallery downstairs in the mess. Mac used to load up on a Sunday morning prior to mass parade, in his number one inspection uniform, and patrol the verandas, scaring crows brazen enough to trespass and drop presents on our passageways.

Dave once regaled us with a tale of an occasion where he awoke on a fresh bright Sunday morning and gazed outside his window over the first-floor walkway onto the inner square as a happy little crow gracefully hopped up onto the bannister next to his window, almost throwing him a good-morning wink. Suddenly the perfect morning scene was interrupted as a swift crack was heard and the crow looked as if it had seen the commanding officer (CO) of the cadet school, before tipping over the edge, one storey below, to its doom. About five seconds later, Mac patrolled past with an air rifle at the ready position and gave a slight nod into the room as if to say, ‘You’re welcome.’ In fact, there are unconfirmed reports that an air rifle was used in taking down a crazed member of a rival passage during a ‘passage war’.

That’s the kind of stuff we got up to when we weren’t cleaning, marching, drilling, cleaning, running, doing stupid tasks for the senior cadets, cleaning, being given lessons and, of course, more cleaning. All these tasks are not designed to make you the biggest neat-freak in the country (just a potentially helpful by-product), but in fact to create a sense of team, discipline and work ethic. Again, it is simple, it is crude, but it works.

They say you make friends for life in the cadet school, and they are right. Mac was my groomsman and Mike was in command of my guard of honour for my wedding. John flew from Sydney to Brisbane specifically to visit me during the time when I was still badly injured. Sully, my roommate from my second year in the cadet school, is now my brother-in-law. He, Mac and other classmates all became part of our skydiving crew years later. They are my friends for life. An NCO (non-commissioned officer, i.e. sergeant or corporal) once said to me, ‘There’s only three ways you can get guys to bond together: booze, women and grief’ (a local term for pain, or something that causes immense discomfort). In this case it was the shared experience of going through that initial ‘grief’ together.

Each character added to the dynamic of the group. Each was expected to grow a thicker skin as we began to develop our cruel military sense of humour. Each was expected to change from civilian to soldier and from soldier to leader.

The officer cadet school wasn’t just about the boring leadership lessons we were given by staff. It was also about the life lessons we took away from the experience of the combined hardship or sense of unfairness. I conducted all of my initial exercises with these people. All of our initial exposure was shared. We lost our military virginity together. We dug and lived in trenches together. We carried backpacks over the various mountain ranges of Ireland together. We delivered our first set of tactical orders to each other. We failed in front of each other. We made asses of ourselves in each other’s company regularly. We, in turn, would have to lead groups of our peers for whatever task or exercise we were carrying out. It was true experiential learning as we didn’t have rank to hide behind. If your peers respected you, they would do what they were told in order to help. This was ‘Learning to Lead 101’. The best lessons were not those taught directly but in fact those learned by osmosis.

Over the course of our twenty-one-month cadetship we were exposed to some really positive examples of leaders. Two of the senior NCOs and one of the officers in particular were superb. They displayed high standards in everything they did, from delivering engaging lessons, to personal examples of dress and bearing. They consistently demonstrated exceptional professionalism in every interaction with us. They expected high standards from us but also displayed exemplary standards in return. The NCOs conducted drill to an immaculate standard at all times and had a biting sense of humour, used to defuse what they must have noticed as nervous new situations for the young cadets.

I immediately took note of this approach. The officer in particular rarely raised his voice or used typical instructor bravado, but instead would deliver creative lessons, showed us what a good set of orders was, and regularly led us through difficult physical training. He encouraged the weak and pushed the strong. During tactics training, he challenged us to be better at our skills and awareness, and would often take extra time to coach and mentor young cadets. He was my first role model in the army. I felt he understood how to be a leader and I watched his interactions intently.

One Saturday morning, a number of my classmates were removed from parade following a uniform inspection. The usual protocol was to withdraw the offenders’ weekend pass, a fate almost worse than death. The officer stated to the group that effort was mostly in the mind. He said he didn’t want to take time from them, so if they showed increased effort and each performed fifty push-ups on the spot, he would not report anyone removed from parade.

During our training, there was also a member of staff who was quite unfair on the class and was hypercritical of our performances. For example, on the rare occasions when this staff member conducted physical training with us, they mostly stood and shouted abuse at us, as opposed to actually doing the exercises. This person placed emphasis on the wrong things during our training and although they fought very hard not to show it, the rest of the staff, officers and NCOs seemed displeased by this person’s actions.

This leadership style led to poor class morale. Their interaction with cadets was rude, aggressive and usually led to some sort of punishment. When they delivered lessons, everyone was afraid to ask questions. If anyone had an issue, the last person in the world they would turn to was this person. This staff member was clearly not a positive example of leadership. Even close to the completion of our training, they maintained their harsh persona, including issuing punishments to certain cadets (me included) right up to our commissioning as officers of the Defence Forces (DF).

In some ways, this was the opposite of the sort of leader I wanted to be. However, in hindsight, this also served as an excellent leadership lesson for me. What did it teach me? It taught me the best lesson I learned during my time in the cadet school – never ever be that sort of leader. Rule number one in my book of how to be an officer is to lead by example. I’m not saying I always do that myself, but I try as best I can and I think people can understand and relate to that.

On a beautiful Tuesday in July 2003, I was handed my commissioning certificate by the Minister for Defence at a large ceremony. I was delighted that my parents, siblings and grandparents were there to witness my commissioning, as my rank was pinned to my jacket epaulettes and I became an Irish Army officer, as decreed by the President of Ireland herself. The sun’s reflection bounced off my immaculate Sam Browne belt as I spoke gleefully with my parents after the ceremony. The hard part is over, I thought, as I regaled them with ‘crazy’ stories from the cadet school. My training was complete and I was clearly now ‘an awesome officer’. Watch out 3rd Infantry Battalion in Kilkenny, because I am ready to lead.

3 Realisation

Kings Beach, Australia – New Year’s Eve 2014

I was quite disorientated, but I remained calm and was fully lucid. A lady outside of my field of view began talking to me. She was firing questions my way as I suddenly started to notice lifeguards rushing around me. I was struggling to respond to her but she kept asking all the basics. ‘What’s your name? Where are you from? What age are you? Who are you here with? Do you know where you are? What day is it today?’ Typical questions used to keep a conscious injured party engaged while monitoring vitals.

I knew what she was doing. I was barely able to muster low-toned responses. I asked her to get someone to fetch my wife. I described how she was up on the grass area at the back of the beach and that she would be sitting with a black Scottish terrier. Not a common sight at Kings Beach one would guess. I asked whoever was listening to be gentle when telling her as I didn’t want her to freak out or get upset. The sun was in my eyes and all I could see in my field of vision were black silhouettes. I had no idea whether there were twenty people around me or just two or three. I wanted to close my eyes but knew I had to stay awake and keep telling the same story over and over, every time someone new came on the scene.

The initial adrenaline must have worn off, as I felt weary. I asked a lifeguard to stand over my legs to block the sun. It all felt very uncomfortable and awkward. Not painful, but very strange. No one had given me any indication as to what was actually going on. I wasn’t sure myself. In fact, the idea of being paralysed hadn’t even crossed my mind.

Then I heard Rita’s voice. She was standing somewhere to my left. I called her to me and she briefly stood in my eyeline. I told her I was okay, that I had had a bit of an accident and it looked bad but I would be fine. I didn’t even know what was going on, but my initial assessment was that because I was able to chat and had a clear thought process, it couldn’t be too serious. I guessed it may be some sort of ‘stinger’, where I was stunned for a little while.

I asked the kind lady I had been speaking with if the young boy who noticed me in the water was around so I could thank him. He was gone. I wish I could thank him. He saved my life, no doubt about it. Those that took me out of the water and their immediate actions definitely made a huge difference to my subsequent recovery, but had that boy not noticed me or alerted anybody, I would have drowned.

Paramedics eventually arrived, rolled me onto a spinal board and lifted me off the beach and into an ambulance. I felt as if there were a lot of people gathered watching the paramedics stabilise my neck and slide the board under me. I felt pain now. The initial shock was subsiding. The realisation that this wasn’t just a stinger or something I would shake off in a few hours had started to dawn on me.

After the paramedics placed me into the ambulance, they tested me for movement and sensation. I felt nothing. ‘Are you sure you’re touching me?’ It was all so surreal, like an out-of-body experience. I had no perspective of whether my legs were even attached to my body. I didn’t know where my arms were. ‘Okay, Billy, wiggle your fingers for me … good.’ I had no idea if I was moving anything. No clue. After some focused concentration and lots of encouragement, I was told I made the slightest of movements in one big toe and one thumb. That was all I could muster.

It was all beginning to sink in. This was serious. Very serious.

Rita sat into the front of the ambulance as one of the paramedics rigged up some morphine. I didn’t feel a pinch but I suddenly noticed the cold rush around my body as the strong numbness kicked in and the pain subsided slightly. They were trying to organise a chopper immediately from the beach back to Brisbane, but eventually elected to drive to the town of Nambour, where the nearest hospital was, as my condition was stable and the availability of the chopper was continuously changing.

As the paramedics stepped outside to make another phone call, I got the opportunity to speak one-on-one with Rita. We were both calm but I stated that I was really lucky to be alive after being pulled from the water, so anything else after that was a bonus. I still hadn’t gone near the thought that I might be paralysed. Whenever I feel sorry for myself, I remind myself of this conversation. It’s important to put things into perspective. It’s a really big message for me to stay grounded, particularly when I’m getting caught up in something, usually at work. Anything else after being alive is a bonus. Lots of people, much better than me, have not been so fortunate.

In Nambour the emergency doctors met me in the hallway and briefed me on the next steps. It was difficult to orientate myself while laid out with a spinal collar locking my face skyward. My perspective was limited to ceilings and various medical staff leaning into the corner of my field of vision.

No one wanted to discuss the obvious. You don’t want to be the doctor who tells someone that they are paralysed, particularly if you are not 100 per cent sure. Everyone was very non-committal when talking to us. ‘Too early to tell’ or ‘there’s too much swelling around the spinal cord right now, we can’t be certain’ was the general response from staff. We both maintained our calm exterior, although it must have been very disconcerting for Rita.

The hospital staff began with a few tests for sensation and fitted a new collar on my neck. They then sent me for an MRI and a CT scan. The MRI machine broke down halfway through and we had to start again. I still had the tight neck collar on, was dosed up on high levels of morphine and was unable to move a muscle.

They rolled my stretcher bed into a room where there was a clock just within my field of vision. It was coming close to midnight on New Year’s Eve 2014. Over the screams of a nearby patient, the doctors gave me the first indication of my diagnosis. One of them said they believed that I had damaged my spinal cord, which had led to paralysis, but they were still unsure how serious it was. They then told me that the best course of action would be for me to be moved to Brisbane and that I would be flown down there to the Princess Alexandra (PA) Hospital, which had a dedicated spinal injuries unit, that night. Once there, I would be seen by the best consultant in Queensland, and it would then be decided whether I would be immediately operated on or not.

With the knowledge of probable paralysis and neck surgery in my immediate future I knew what I had to do. I had held out on letting my family know what had happened until I had a better understanding of my diagnosis. Now I asked Rita to hold the phone up to my ear. This wasn’t going to be easy. I broke the news to my mother, and I have to say her initial reaction was better than I thought. She was calm and collected. I found it difficult to actually say the words ‘I’m paralysed’ to her, and it upset me actually saying it aloud for the first time. But it was good that I was able to speak to her personally. I think it gave her, and my siblings, whom I also called, a huge sense of relief that I could actually talk over the phone.