Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: ONE

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

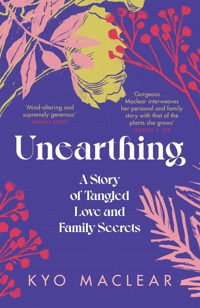

A STYLIST BEST NON-FICTION PICK 'A lucid and compelling memoir of family rupture and repair' Sue Stuart-Smith, author of The Well Gardened Mind 'Gorgeous and generous . . . a mind-altering journey that challenges biological determination' Naomi Klein, Esquire Three months after Kyo Maclear's father dies, a DNA test reveals that they were not biologically related. All at once Kyo's silver-haired mother becomes a mystery to her; she holds the story of a secret buried for half a century, but her memories are fading, and words are failing them both. Maclear does not speak Japanese and so to unearth the past, she must turn to her mother's second fluent tongue: gardening. Unearthing is a memoir written in the wild green language of soil, seed, leaf and mulch. With exquisite illustrations by the author, this is a tribute to the ineradicable love between a mother and daughter.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 414

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise

‘In this magnificent, searing memoir, Kyo Maclear takes us on a journey that is at once singular and utterly universal … I will never forget it’

DaniShapiro,authorofInheritance

‘A mind-altering journey that challenges biological determination, while rooting family in the daily practice of care and love’

Esquire

‘As she uncovers her family history – including previously unknown Jewish ancestry – she meditates on the nature of marriage, fidelity and familial love, while seeking an affinity with the natural world and solace in a love of gardening inherited from her mother’

Observer

‘A tender and precious gift of a book, that holds out grief like an opening flower. Deeply moving, beautifully written and delicately delivered’

VictoriaBennett,authorofAllMyWildMothers

‘Mother and daughter begin to tend a garden together as Maclear begins to unearth the past’

Stylist,Best Non-fiction Books Released in 2024

‘A masterful lyric exploration of identity, inheritance and belonging in the wake of an unsettling discovery, that deftly queries what makes us who we are’

PollyAtkin,authorofSomeofUsJustFall

ii

iii

iv

v

For you. Haha ni aiwo komete.

yoko (mariko) maclear 1937–2024

vi

vii

But what is the point of writing if not to unearth things …

annie ernaux

viii

Contents

COLOPHON NOTE

the japanese traditionally record the seasons in twenty-four sekki, or “small seasons.” I have borrowed the names of sekki(節気) as section titles to offer a different way of thinking about the ever-changing ground of our stories.

prologue

ma was a gardener. where she saw gradients of celadon, emerald, sage, olive, I saw only a thin green blur. When given a plant by someone who thought I looked capable, I would start out full of hope. I admired the buds for opening with confidence and the buoyant way the leaves unrolled. But before too long, the sprightly leaves would wilt or crisp. The Madagascar jasmine, enfeebled by too little sun or not enough water, would sigh toward the ground. The peace lily, overflooded with daily attention, would sag and expire. All the sad plants … I could not, in spite of my mother’s effortless example, and my effortful efforts, keep them alive.

Then things took an unexpected turn and what I had dismissed as notformebutformymothersuddenly moved to the fore. In early spring, 2019, it was determined through dna testing that I was unrelated to the man I had always thought was my father. Well into the journey of my life, the imagined map of my family, with its secure placement of names and borders, was suddenly very wrong. All at once, my silver-haired mother became unknown to me. She had a big story to tell, a story of a secret buried for half a century. A story that she struggled to express—or had no wish to express—in her adoptive language, English.2

I wanted my mother’s story. I wanted a tale that could put my world back together. But each time I pressed, my mother shook her head.

My mother had never really liked stories. She looked at them with suspicion. All my life she questioned both the ones I read and the ones I wrote. All my life, she asked: Whatareyoudoing?And nine times out of ten, I replied: Iamwritingor Iamreading. Both answers brought forth thelook. The look rightly asked, Whatpurpose is there to your efforts?The look accurately said, No one can eatastory, noonecandineonabook. On the rare occasion someone commended my writing in her company, she bore a weary smile. A smile that pitied the speaker for not realizing there were better, more reputable products out there; better, less soft ways to spend a life. But the look also said: Don’tsquanderit.Writesomethingworthyandpractical …writeaplantbook.

In 2019, what did and did not work between us was now irrelevant. All the ways we had been at odds in life no longer mattered. I needed to understand my mother better, and the only way to do so was in the language she knew best. Given the state of my forgotten first language, Japanese, I chose her second fluently-spoken language, the one she never pushed on me: the wild and green one.

This is a plant book made of soil, seed, leaf and mulch. In 2019, I turned to the small yard outside our house and the plants my mother had woven into my life, to bridge a gap between us. The yard was scruffy and overgrown. It belonged to the city, to the bank and, most truly, for thousands of years, and still, to the Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg. With my sleeves rolled and my fingers mingling with the rose-gray earthworms, I set to work.3

It did not go well. Not at first. The garden quickly informed me: I did not know plants. I knew only my ideaof them, and you cannot grow an idea. The garden said: Thiswillnotworkifyouareonlyhereforthemetaphor.The garden asked me to remember the child I was, a child who loved getting dirty, and to remember that first lesson: Nothinggrowsifyoukeepyourselfclean,smooth,undisturbed.

When I stopped attributing every little plant event to my own doing and realized I did not have control (the opposite of a storyteller’s mindset), the plants began to grow. When I remembered that plots are often driven and overturned by underestimated agents, I stopped underestimating.

A mother enters a story. But how does she enter? How does she walk across the pages of a book? Does she enter wearing her regret, rage, sadness or humor? Does she enter boxing away clichés and pushing against containment? Does she enter demanding payment? Does she enter as a gardener?

I learned more about my mother’s plant passions, to feel the events and landscape that passed through her heart, to take stock of what I had failed sufficiently to notice and love—the unseen greens, the hazy “scenery” of life.

I am the sole keeper of my family’s stories.

“What stories? Why stories?” she says.4

january–march 2019

one:

DAIKAN (greatercold)

7the beginning

when my father died and i was still his daughter in all ways and without question, I began making weekly visits to a public greenhouse. For seven Mondays, I rode the streetcar across town to warm myself in a glass building full of plants. No one had warned me that hard-hitting losses sometimes take the form of ordinary problems such as temperature-related discomfort. I had not seen this play out in stories, so I was not prepared for the cold current that entered my body and spread like ice through my veins. I did not know ski gloves and wool fleece would be my mourning vestments.

For seven Mondays, I sat with leaves the size of airplane wings under a glistening dome. I basked in winter sunshine, buried myself among the dripping fronds of palms and cycads. The busy trees put on a good show as I folded inward, as the vines tunneled through me, binding the grief. Slow,slow, the leaves and petals moved at a pace I understood.

For seven Mondays after my father died, I came to this glass church to sit with the plants and feel their deep sweat. It now occurs to me with some curiosity and a little sadness that people, particularly the “faithless” and those without reliable rituals, grieve in unusual places and that these places are not always so obvious. We all have ideas about what happens after a loved one dies but these ideas are often wrong or, at least, incomplete—because everyone has a different grief and, therefore, a different bereaved state of being. 8

when my father died, when I was still his daughter in all stories, those he told and those I told, I was tasked with funeral arrangements. A week after his death on Christmas Day, he was returned to me in a purple velvet pouch. The funeral home sent the ashes directly to the cemetery and they were waiting for us at the reception desk, in a sack so reminiscent of a Crown Royal bag I would not have been surprised to hear D&D dice rattling inside. “Please check this,” said Maria, our host, inviting me to confirm the name on the box inside the bag. I nodded, Yes,this is my father, as tears pooled quickly in my eyes and the room with its solemn chairs and my seated sons became a swimmy blur.

“I lost everything this week,” I overheard my mother say to a man offering her coffee in the corner. “I lost my husband and I lost my Air Miles card.”

In keeping with his wish to be buried with simplicity and privacy, we were the only people present at the service. At the end of our short, improvised ceremony, my husband sang a song. When we first married, he was studying to be a professional cantor, but ended his training when he was told he could not continue unless his non-Jewish wife converted. Now, as we stood close in a huddle, the bended beauty of his voice twisted and twirled in the cold air, ribboning the sky like a bluesy liturgy. “You chose a good one,” my younger son whispered to me with a nudge and nod in his father’s direction.

Shoveling dirt into a grave is hard work. The ice-frosted mound would only budge with great exertion on our part. Don’tworry, said Maria, wecandothatforyou.But the physical labor was 9soothing, so we kept chiseling and shifting clods of soil. The air filled with slow, percussive thuds as we took turns spearing the spade into the ground, jumping on it a few times so it would cut sharply downwards. Maria told us again not to worry. She nodded toward a groundskeeper a few meters away, a man I noticed for the first time seated in a small backhoe, wearing a fur flap hat and mirrored sunglasses, who now slowly raised a hand in greeting. Thud,thud,thud.A frozen wedge toppled. My sons’ digging and grunting movements were determined but somehow upbeat: they would tuck their grandpa into the earth and bury their mama’s grief.

Walking from the gravesite across the frozen ground, I made out the blunt tapping of my mother’s cane behind me. “I was hit by a car a few years ago and injured my foot,” I heard her say to Maria. “I could have been killed! But I am a survivor!” A village of human dust lay beneath our feet. “I am a survivor,” she repeated, this time waving her arm around as if to say, Clearly,Iamnotoftheirnumber. Then, after the briefest of pauses, Maria replied: “Well done.”

asimpleone, my father said, when asked by his lawyer what sort of funeral he wanted. He wished to be cremated at a modestfuneral site,that the attendance be that of my family only,that theexceptionmightbemyhalfbrothers…He wished fortheashesforamomenttoblazeoverthehomeofthoseIlove.

my father was a dramatic storyteller and now there was no story. The car on the way home felt quiet and empty, even though it was full of us.10

When one person leaves, the old order collapses. That’s why we were speaking to each other carefully. We were a shapeshifting family, in the midst of recomposing ourselves. What is grief, if not the act of persisting and reconstituting oneself? What is its difficulty, if not the pressure to appear, once more, fully formed?

during those winter weeks and months when I began visiting the greenhouse every Monday, I craved rooted, growing, ongoing things. Rolling moss, misty leaf, moist vine. I wanted more leafof all kinds: wispy fronds, bubbly strings, wide strips, loopy lines, huge paddles, serpentine ivy splaying like my heart in all directions.

I missed my father’s charm and his sly humor. As far back as I could remember, my favorite activity was to sit with him and have long conversations about politics and life. If someone had asked why I was hiding under glass, I might have answered: I am waiting.

My father’s last months had been very hard and after the medical chaos of his final weeks, when his body hurried deathward, it was a relief to have him sheltered inside my heart where it was safe, but I still wondered when we could chat again. A part of me did not accept the situation’s irreversibility; could not believe that nothing new or unplanned would ever happen again. I’ll see him on my birthday, I thought, holding out for another moment. I was still only at the beginning.

In the Cactus House, one morning, imagining I was in the driest desert on earth, drier than Death Valley with its prickly pear and prowling coyote, I studied the arms of one spiny pillar in particular, thinking about the genius of adaptation. A cactus’s entire life 11is about protection against insects, predators, the elements, and that’s why they are scarred and wrinkled. They have been through some things.

A man in a blue chore jacket emerged from the potting shed with a drip tray full of plants with fingery leaves, upraised like birthday candles.

Blue chalksticks, he said.

Wheredoyoubelong,bluechalksticks?I wondered.

They’re from South Africa, he said, reading my thoughts.

what immense journeys had these plants endured, across oceans and seas, occupied lands, through dramatic shifts of weather and landscape, parted from parents and community, to arrive in this living museum, this plant zoo, brimming with pampered “exotic specimens”? What had they lost?

One night, I began reading Jamaica Kincaid’s old gardening columns. Openly enchanted by the deep history of plants, Kincaid described how the world of the garden changed in 1492 when Columbus set sail from Spain. She traced snared histories of violent transplantation and radically transformed landscapes, the grand dreams of landed gentry enthusing about native flora, the looting in the name of inventory and order.

But she also insisted the colonial encounter was not a finished or unidirectional story. And maybe this was why I came across visitors from all over the world at the greenhouse, each with a different history of migration. The plants might have been a strange mix, opening and closing at the wrong time; the clusters of orange clivia and hibiscus clearly out of season. But, still, people 12sat with the floral riot, to breathe familiar smells and for a moment be among others far from their homescapes. The well of a “backhome” flower was not just a fraught vortex of loss but also a deep, fortifying pleasure.

Much to my surprise, I was falling in love with greenhouses in general, and this one in particular. I was falling in love with the plants and people that gathered in this magical, fragile, neglected corner of my city.

there were mondays, when at certain moments, I felt my father, the person I most wanted to be earthbound, everywhere. He was there in the ferocity of my missing him, in the bright smell of green. At certain moments, I felt light. I felt buoyant.

my favorite room at the conservatory, after the Cactus House, was the Palm House with its cathedral ceiling. This is where I came to eavesdrop on conversations and this is how I knew that others, quiet as orbits, were lugging phantoms too, carting them to this place where they could be freely acknowledged. The windows were fogged with trickling ghost breath. The inverted glass jar, which we knew as a conservatory, held us in a bubble of soft dewiness. This is what it must feel like to live inside a terrarium, I thought.

One Monday I saw a long-haired woman alone on a bench, a guitar case at her side. She had a French-chanteuse energy. She was wearing a shaggy calamine-pink coat and looked up at the domed glass above her head while quietly weeping. She seemed to have lost someone and I assumed it was to death, because there were 13many deaths around the time my father died. As my Uncle R. put it, the portal between the living and dead was very open. Thegateswere free for coming and going.

The portal took Jonas Mekas, Diana Athill, my dad’s friend Joe, Tomi Ungerer, Ann’s mum, Kathy’s dad, Deborah Bird Rose, John Burningham, Brenda’s dad, Andrea Levy, Mary Oliver. I imagined a convocation. In life, they may have been of differing stature, but in death, to their loved ones, the members of this sad cohort were all on the same plane of loss.

In the Palm House, I watched the no-longer-weeping woman press her cheek and nose against the cool foggy glass, leaving a wet silhouette, before continuing on her way.

A conservatory worker, an Asian woman who looked to be in her sixties, sang to herself in an atonal hum as she placed small shoots under a twisting screw pine and watered the dark beds with a hose. In that moment, I had a memory of my mother, not long after my parents separated, hiding in the final garden she created. I saw her kneeling in the soil, surrounded by shaggy fern and stiff-postured horsetail, and I saw her hands in action. Hands bright but calloused from the work of raking and shoveling. I saw her hauling manure, burying, unearthing, patiently planting. Dirty hands and unalloyed happiness.

Most Mondays it was snowing. The light kept shifting in the small green world. The sun that reached through the conservatory windows glowed weakly. But somehow that weak sun filled me.

Sometimes, while I sat in the conservatory, my mother would text me voluminous paragraphs in Japanese. “Why don’t you 14speak your mother language?” she wrote when I replied with a question mark.

back at home, my sons greeted me with a hug and a “Hey Mama” before rolling off to forage for food or games or a couch to flop on. Occasionally, I heard them whispering, worried they might have to wait a little longer for their mother to stop leaking tears into the salad bowl.

My older son gifted me a pack of bubble gum with a look of sacred seriousness. My younger son lit incense at our Buddhist altar, dinged the singing bowl three times with noisy solemnity, and offered up long and focused prayers. One Monday on my way out to the greenhouse, I stared at his back as he knelt to pray, I stared at the inwardness of his prayer, the way he sat in his own solitary dimension, and the heat kicked back on in my body.

That was my last Monday visit. I had spent seven weeks at the conservatory to mark my father’s passage between worlds. I had gazed at the sky through all the different windows.

In many Buddhist traditions, seven weeks, or forty-nine days, is the traditional mourning period. On the forty-ninth day, the spirit arrives at its destination and attention is returned to the living. It was time to break the glass case and leave the small green world for the wilds. I would show my sons it was okay to let others hold you and unsequester the sadness as it worked its way through you.

The father I had trapped in my mind needed to be free, his spirit needed to ascend.

15curses

when my father left the planet and i washis earthbound daughter, his much younger brother arrived for a visit from England. He had news to share. My uncle R. told me there was a love curse on our family. The curse was six generations old, he explained. A Swiss psychic named Anita had told him so. According to Anita, six generations ago, an ancestor of ours had thrown his mistress off a cliff. Because of this we, his descendants, were in spiritual trouble. Burdened by his crime, we were destined to be adulterous, to be married but unhappily, to nurse unhealthy addictions and endure frosty emotional connections. We would forever have difficulty expressing ourselves and form nervous, ambivalent attachments. Thus, we would be able to love others or be loved only in passing or from a suspicious distance. We would, in all likelihood, die alone. The curse, which had afflicted my Casanova grandfather and my restlessly single, often cruising Uncle R., apparently, had also lodged in the Catholic priest to whom the murderer confessed but, in that case, there were no descendants.

My uncle had flown to Toronto to attend my father’s memorial. A few days before he landed, our furnace broke during a record-breaking cold spell, causing our water pipes to burst—so we were huddled by a portable space heater in a kitchen that smelled like river while a contractor opened walls. The arctic weather in our house was a mild difficulty in the scheme of 16life-and-death, but it was likely the reason I felt so cold all the time. I knew my uncle to be the sort of person who believes there are spirits in the basement of his office, tampering with his business. So while we shivered, I waited for him to outline the steps necessary to exorcise the curse. I had entered the “burying years,” to use Marlon James’s sad and powerful phrase, and it seemed a good idea to properly bury all the unnecessary things lodged inside my family and me, all the patterns and configurations repeated, the injuries and inheritances that preceded my arrival, which now included this genealogical shadow I might have been dragging around unwittingly. But my uncle, adjusting the wool blanket on my shoulders, had switched to a new conversational topic.

The curse was never mentioned again. My mystic-minded uncle returned a few days later to Sussex, where the first swallows had reached Britain’s south coast a month earlier than usual, where the air was unusually perfumed with early-blooming flowers, surprising those who still believed in the predictability of seasons. I was left to consider it all.

The truth is, the question of what made the artists and writers in my family so fiercely self-reliant and lonely had bothered me more with each passing year. I did not like the family tradition of dying alone. Where were the examples of lovers who grew old together, the life companions who gentled into a comfortable twilight?

The possibility of an unresolved trauma being passed down from one generation to the next was as credible as the lineal transmission of ways of walking, talking, speaking. But this love curse my uncle described did not sound like mine. It sounded rather like the curse of white manhood, to which some members of my British family owed their cool detachment. My blockage, my own 17tendency to hold others at a remove and become frozen and folded inward at times of crisis rested elsewhere, I suspected. I didn’t know where. Or what karma across lifetimes had made me, at key moments, so scared to unguard myself. I only sensed my spiritual trouble had little to do with the horror of a woman being pushed off a cliff in Victorian England.

18love

when my father died, and i was his daughter in all blessed and cursed circumstances, I thought about love.

The story of love labors under many curses. The curse of soppiness. The curse of romantic dogma. The curse of insecurity. The curses of capitalism and hearts replaced by gold and gemstones. The curse of possessive communion and domestic captivity. The curse of planetary human-centeredness. The curse of private property cloaked as “loving one’s own.” The curses of mistrust, timidity, generational trauma, an overactive amygdala and hazardous addictions. The curse of squashed ardor and no infinite mystery. The curse of mixed feelings and little deceits.

I had spent far too much time pondering a deviously simple question, one that would be obvious to anyone who was not born apprehensive: What’sthedifferencebetweenloveandfear?(There is no difference, was the answer I divined from a psychology book titled AGeneralTheoryofLove. “Many of our ultralow-anxiety ancestors were bitten by snakes, gored by tusks, and fell out of trees.” In love as in life, one must learn to creep “from beneath the protection of a fern.”)

The truth was I knew very few people who relaxed easily into love, operating without an ounce of doubt. Inexpert as I was at love, I wanted to do better for my sons and put forth a new 19repertory of habits and options. I did not want to be shut down and withdrawn. I had been trying since they were born to create a better operating manual. Could we crack the curse or pattern and proceed like eager puppies, holding nothing back? Could I be anything but a wobbly love guide?

20grandmother

when my father died and i was his daughter asking questions about love, I became a sleuth. Under protection of a fern, my aim was to get to the bottom of the curse of fearful attachment, which I sensed was connected somehow to the mystery of my Irish paternal grandmother, Carlynne Mary Gallagher, a woman who did not reach old age and about whose life there were very few details. My father, raised in foster care, hardly ever spoke of her. “Let’s talk about something else,” he said, whenever I asked for a childhood memory. All I had was her name, a photo the size of a chocolate square, and some offhand remarks made by my uncle and my father’s now-deceased stepmother. One comment, in particular, had stayed with me, words repeated by my uncle during his recent visit. Shewasdepressive.Troubled.Notquitewell.

Not knowing my grandmother had made her feel eerily close to me, closer than almost anyone. She had come to represent all the unknown things; all the tangled feelings that needed to be unwound to the source if I was to understand more about our family and the genealogy of our phantoms.

I set off to do ancestor repair work, to give my ghost matriarch a shape and shake her free from the silence that had erased so many women from our family history. In the old days, I would have pored over microfilm, scoured through ancient cardboard boxes, scraped the dirt off proverbial gravestones. Being a detective is so easy, almost instant, nowadays. Within a few hours I had 21tracked down her marriage and death certificates and discovered she was not always a ghost with a fitful relationship to happiness. She was a baby once (Chelmsford, 1904), a baby who had two younger siblings, only one of whom survived childhood; a baby who became a girl who became a woman; a woman who fell in love, got pregnant (1929), shotgun married (Paddington, 1929), had a son/my father (1929), changed nappies and nursed her son through a severe case of the mumps, was left by a womanizing husband who would try to hide the fact of his marriage and child entirely, gave her son over to foster care (1933), never remarried or had further children, and died at age fifty-five (St. Pancras, 1959).

The barest biographical facts. Maybe she loved jazz, Branston pickle, steep impractical shoes and whodunit novels. In the meagerness of detail, my new mission was to find someone, maybe a Gallagher, who might have known her. One anecdote, one memory, one more photo, was what I wanted, but also an answer to the question: Was there any truth to my uncle’s offhand remark about her mental health? And could this history reveal anything about the vapor of depression-anxiety that had carried forward to my father, myself and my younger son, possibly pressing its way into our genes?

In a 1997 performance titled Sometimesmakingsomethingleadstonothing, the artist Francis Alÿs pushes a large block of ice through the streets of Mexico City until it completely melts. After nine hours the block is reduced to no more than an ice cube, so small that he can casually kick it along the street. I imagined somewhere back in time a large and obdurate block of sadness that was being pushed through generations, awaiting a hot sun. But this was mythical thinking and what I wanted was to return this shadow history to the material world and proceed with all the data in hand. I wanted to build a story around the tiny photo of my 22paternal grandmother that sat on our family altar and maybe undo some of the lingering stigma surrounding mental illness. To find someone to speak to and remember her, to trace the origins of our epigenetic sadness but also our epigenetic joy and strength, that was the idea. Let all our demons and angels into the light. Let us face the clout of ancestry. Building a true story, I thought, might protect us from becoming heirs to hearsay.

My father, the person who knew the most, had just exited the room—leaving clothes, books, papers and the flotsam of care scattered in his wake. The answer couldn’t be found in what he had left behind. While he had maintained some contact with those connected to his father, he grew up and away from the relatives on his mother’s side. I needed another path to those who might have knowledge of the challenges and hardships she faced that were hers but maybe also, constitutionally and historically, ours.

A dna test, my friend suggested.

23mystery

when my father died and i was his grieving and wondering daughter, I thought of a word. The word, yugen, or what the Japanese call a state of “dim” or “deep” mystery, evokes the unsettled feeling I had at various points growing up as an only child. Our family was a tiny unit with strange ways. My parents acted like criminals on the lam—loading up moving vans, changing house every few years. I was four years old when we left England, shedding backstory and friends overnight. What made a family behave this way, like people drawn to erasure? Why were we always leaving like this, so unceremoniously? I did not know. Growing up, I assumed that everyone was shaped and suffused by what they could not perceive clearly, the invisible and voiceless things imparted atmospherically within families.

The first time I introduced my husband—who was then my boyfriend—to my mother, she greeted us at the door in a bra and underwear.

“We don’t really talk about things,” I said when my mother went to fill the kettle for tea. “In our family everything is kind of tamped down.” I watched my sweet, naïve boyfriend forming opinions in his head and I wanted him to know you can be the kind of person who openly greets a stranger in undergarments but is closed in other ways.

24test

when my father died and i was his doubtless daughter, I stared at a small white cardboard box. The DNA kit came with Terms and Conditions, which included information about data privacy and a statement that read, “You may discover unanticipated facts about yourself or your family when using our services that you may not have the ability to change.” In late January 2019, I spat in the plastic tube and put it back in the box.

I did not see myself as expressing fetishistic wonder about my ethnic roots and genetic predecessors. I did not wish to “[track] down the exact ingredients” of my “European genetic cocktail” (Joshua Whitehead) or feel “wistful for aristocratic origins” (Saidiya Hartman). Coming from a mixed-race family, I had no patience for chauvinistic kinship narratives or the treacherous idea of purity. From a young age, I noticed that Japanese people did not regard me as recognizably or legitimately Japanese, did not view me as one of their own kind. I noticed that white people saw me as veryAsian. I was used to inconsistent reactions. They were commonplace. If we hybrids have a superpower, it is the ability to side-see, to scour the periphery of stories and a heritage industry that view the world too narrowly. We know the world is a continuum of polar things, and the words “my people” and “my roots” can be a carnival of confusion.

I took my muddy urge and mailed off the box. The kit was prepaid. I did not expect anything remotely surprising. Not for 25a moment did I consider that some of the things I’d assumed basic to the story of who-I-amand where-I-come-fromwould be revised.

25circle

when my father died and i was his daughter at work and at rest, I traveled alone to a residency in the mountains. What was to be revised appeared in my inbox as I sat alone in a room, 4,500 feet above sea level. What I saw was a circle bisected into two halves. I had inherited half of each parent’s DNA—but the paternal half bore no resemblance to my father’s genetic history, at least as it had been told to me.

An error, I thought. A glitch. I casually refreshed the page several times, tapping my cursor as though it were the “spin” button of a slot machine and the reels of cherries, bars and lemons might, through repeat attempts, align in a different pattern. The page did not realign.

I texted a screenshot to my husband.

“A mistake?” he replied.

A minute passed.

“You don’t even like herring,” he added.

A few minutes later, he texted again.

“MazelTov, now you know what that means!”

alongside my dna results, the company provided migratory maps of my ancestors, which showed my paternal family originating 27from Lithuania, Latvia and Belarus. I had never heard my family speak of any of these countries.

For a fleeting moment, I wondered if my dad’s assumed ethnicity was 100 percent wrong—if he wasn’t who he thought he was—but then I remembered the records of my Irish grandmother and the names on my father’s birth certificate and the documents tracing the Maclear lineage back multiple generations. From those details and the endless scroll of strangers appearing as my closest relative matches, it became clear: the test revealed something else. I closed my computer. I didn’t know what to do with this news except to start walking.

Alone in the mountains; the sun flamed. No half-obscured low light. Just brilliant, blazing warmth that felt like relief. Inside the chamber of my heart, I carried a list of facts and a list of feelings. I tried to get them to speak to one another as I walked by the river, where great slabs of ice were loosening. The sun-shimmering plates shifted and collided in a ballet of solidity and solubility.

Among the feelings I carried was my own raw shock, I realized, but also shock I felt—or assumed—on my father’s behalf. I imagined having to one day explain to him, the man I had always known as my father, what I had done, how I had stirred up trouble yet again with my curiosity and capers. Surely an awkward and heartbreaking conversation at the best of times and towards the end, when my father’s memory faded, one that would have been greeted with a baffled half smile. Still, his death was not far away enough for this imagined dialogue to feel implausible.

The two griefs I now felt shifted and collided. The grief of his dying followed by the grief of having our story break down and crack up as a result of my impulsive action.28

When I returned to my room, I lay down. A couple of hours passed and during that time I lay very still and made my mind blank. At some point, I fell asleep and woke up to a glowing blue window.

near the end of my father’s life, I befriended a neuroscientist who told me a story of his nephews traveling on a plane for the first time. My friend was seated a few rows ahead of them. Shortly after takeoff, the plane was hit by severe turbulence, which rocked the cabin and sent belongings flying everywhere. Passengers were screaming. Worried for his nephews, who were surely experiencing the same stomach-plummeting terror, my friend looked back to find them with arms raised, cheerfully shrieking: ROLLERCOASTER!

I was struck by this story, by his nephews’ joyful bubble and their ability to experience upheaval as adventure. Was it the joy of young children tossed into the air, knowing there would be waiting arms and rescue? Was it the effervescence of those who do not possess crash data?

In the early spring of 2019, I found myself thrown clean from the seat of my old story. There was a feeling of falling.

Forty-nine years after my birth, when my father died, I lost all feeling for certainty as the ice floes were breaking up.

march–may 2019

two:

SHUNBUN (springequinox)

31little peach

my mother liked to tell me she found me as a baby floating on a river. I arrived inside a large peach blushed with rose and when I emerged, I was so bewildered, sticky and small, she had no choice but to bring me home and rinse me off.

She told me this story a dozen, two dozen times, before I realized she was telling me the story of Momotaro, one of the most famous of all Japanese mukashibanashi, or folk tales. In the legend, Momotaro appears on earth to become the son of a poor, “barren” couple whoeverydayandeverynightlamentedtheyhadnochild. Now elderly, the couple find their youth and happiness rejuvenated by Momotaro’s arrival. Solostwithjoyweretheythattheydidnotknowwheretoputtheirhandsortheirfeet.

The story, the only one my mother ever told of my birth, spoke to me and said a family could occur by happenstance and strange handiwork. A gathering of currents could carry a baby toward a random port of arrival. Some origin stories have human fingerprints all over them but this one, I thought, must have been written by an orchard. Only once did I wonder out loud what the experience of miraculous birth must have felt like from Momotaro’s perspective: Wasitscaryinsidethatdarkpitofapeach,Mama,rolling alongthatquickwatertowhoknowswhere?

In mid-April 2019, the results of a second DNA test confirmed the first one. My ancestry composition: 50 percent Japanese and 50 percent Ashkenazi Jewish.32

I worked up the nerve to call my mother, preparing myself. How difficult could it be to get the truth? HowwasIconceived?There was nothing to do but ask.

When she finally understood what I was asking, she fell uncharacteristically silent. I listened to her breath, the sound of rustling paper. Waitaminute, she said, and put down the phone. I heard her walking across the floor, the sound of a kettle being filled at her kitchen sink. Iammakingtea, she said from a distance.

Then, as if we weren’t in the middle of a conversation, she picked up the phone and asked if I was cold. She told me she had received a letter from the cemetery and read the heading aloud: “Customer Satisfaction Questionnaire.”

I asked again.

Itwasdifficult, she said finally. Wetriedforsolong…forsevenyears,solong,Iwantedtohaveababy.

She told me my father arranged for her to go to a clinic on London’s Harley Street to see a doctor. It was the obstetrician-gynecologist who would later deliver Princess Diana’s babies. Averyspecialspecialist!The doctor placed her under a general anesthetic and later, when she awoke and asked what happened, my father said: “Everything will be fine.”

Everything will be fine?I repeated. My voice had thickened. What did he mean?

He was the one who made the appointment, she continued. Youshouldaskhim.

She repeated it three times. Talktoyourdad. As if his death had been a hoax; her voice no longer blurry but brisk with fear.

33head gardener

“yes, let me talk to him,” i thought, as i sat on a bench listening to the discourse of two house sparrows trapped in the Palm House. I had returned to the greenhouse for a private tour that had been arranged months before. As my story landslided and uprooted, it felt good to be domed to the earth.

I craned my neck to look at the glass ceiling and imagined fire licking through the original dome, as it had in 1902. For several minutes, “the cracking of the flames was relieved by the curious tinkling sounds of thousands of falling panes” fracturing from the ceiling, the OttawaJournalreported at the time. Many of the plants were scorched to a crisp, and the structure itself was reduced to “a heap of ruins.” A new crop slowly took root when the Palm House dome reopened in 1910.

The head gardener, a muscular man with close-cropped hair and a studious smile, had arrived and was now using his well-built arms to explain how branching greenhouses had been tacked onto the sides of the Palm House. I followed him to the Tropical Landscape house, where he showed me a rare cycad tree. Then to the arid room where he acquainted me with a barrel cactus and jade plant that had been companions for fifty years. I tried to concentrate on what he was saying but it was bright, too bright to focus on any one spot, with the light bouncing from the white sky to the dirt-fringed windows. Youmightnoticethealoeisbrowned…weleavethescruff.Undereverythingisold-growthandyellowleaf… 34theimperfect … His measured words floated above my wavering thoughts, until they rose high up near the glinting ceiling.

“I believe plants have feelings, so I will never tell,” the head gardener whispered when I asked him if he had a favorite plant in the gardens.

35something

it was all being pulled from some shadowy room. The details she remembered. The broken chain of events. What she spoke arrived in fragments. But there was something else, a hitch and hesitance, that made me alert.

I did not yet understand the need to hold on to an invented story, even a falsified past, at all costs. I did not recognize her dissembling. Usually impervious, I thought she seemed out of sorts. Maybe a little distraught.

She does not want to tell me something, I thought.

36facebook

npe is short for “non-paternity event”—or, more colloquially, “Not the Parent Expected.” NPE is one way a life story can swerve, and here I joined others who had come upon accidental discoveries, who found themselves stumbling for footing on terrain that was no longer dependable.

DNANPEFriends, self-described as “the best club you never wanted to join,” involved an online intake questionnaire, beginning with: Whattestdidyoutakeandhowareyoudoing?The woman vetting requests was a former member of the NYPD and had recently retired from a global security firm specializing in protecting “enterprise-level facilities from high consequence threats.”

There were many steps in the admittance process to this secret Facebook community, the last of which involved a promise that I would not publicly share any of the posted stories or names in the 8K–member group. “Let me give you some abbreviations and guidelines,” said the moderator. “BF is Bio Father, BCF is Birth Certificate Father, HS and HB are Half Sister and Brother. DC is Donor Conceived … There are no F bombs and only thoughtful and compassionate posts. We don’t tell anyone ‘to get over it.’” Then finally, the gateway opened. A welcome post appeared with my name, festooned with pink hearts.37

Everyone new to the group was saying a variation of the same thing. GeneticBombshell.Notinathousandyears.Brainnevershutsdown.Slippingoff theedgeof theearth.Reassuremeit’slikethisforyoutoo…

I quickly lost myself in the bounce and echo of emotions, feeling sparks of solidarity and synchronicity. Our stories were starlight, blinking and flashing for connection. Our stories were all the same. We were here because we had the same issue, the same condition. Affirmations were instant and insistent.

Some of the people in the group had come out the other side by solving the puzzle of their misattributed paternity. A woman named S. was having the most monumental day of her life, meeting her HB for the first time. A man named T. was hugging the HS he never knew he had. In the photo they wore matching T-shirts, underlying the recurring theme of family “likeness” as tether.

But the question remained: What about those still in limbo? Many people were still searching years later, wandering genealogical hallways. Some had made peace with the perpetual search, as though it were a game or riddle that did not need an end. Others found the endlessness to be a nightmare. “I don’t think I can accept ‘not knowing’ as my biological paternal parentage,” said one woman with a sobbing emoji for punctuation. With a missing first chapter, she worried her story would always be a deficient narrative. And then there were a mysterious few who seemed to cling to limbo by choice, resisting leads, unable to summon the psychic strength to take the next step.38

I lasted only a few hours. I have never been a comfortable congregant. In quantity and in volume, the sharing of stories felt dubious and overwhelming. I returned only occasionally to see if the searches were thinning out.

39harley street

of course, my mother did not know the agreed-upon abbreviations or updated terms, which might have made the storytelling easier or at least less messy. The right terminology could have offered a banister. As it was, her story was a blur of waiting rooms and wards and curtained-off beds. It contained doctors and invasive procedures. It contained a possible verdict of severe childhood mumps leading to paternal sterility and the end of so-called “natural options.” It contained a scared woman and a husband who whispered reassurances.