4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Feminist, socialist, trenchant social commentator, Nell has seen and lived it all. From the early days of the civil rights movement and the revolutionary fervour of Free Derry to the bitter conflict at the Garvaghy Road and the Siege of Sarajevo, she has been both a participant in and a witness to history in the making. Writing about it all in her own way, and as nobody else ever could, the force of her passionate pen has won her a place as one of Ireland's best-loved journalists. Here are moving accounts of the numbed aftermath of Bloody Sunday; of the lonely death of Ann Lovett in 1984 and of the shock of the Kerry Babies case a year later. And in excerpts from her acclaimed 'In the Eyes of the Law' series we meet Maoists, Hare Krishna monks, wife-beaters and 'adult consenting males' confronting the Dublin District Courts. Taken from sources ranging from The Irish Times, Irish Press and Sunday Tribune, to Hot Press, Kerry's Eye and Magill, Vintage Nell harvests the strange fruits of Irish social and cultural life from the seventies to the twenty-first century. It features classic accounts of the Pope's Visit in 1979 and of the 'dirty protest' of women prisoners in Armagh Prison – and sympathetic, raw, incisive cameo-portraits of Ian Paisley, Martin McGuinness, Raymond Gilmour, Bishop Casey, Mary Robinson, Winnie Mandela, Mo Mowlam and others. From the serious – 'Reservoir Prods', 'Chernobyl' and 'The Life and Death of Mary Norris' – to the witty and satiric – 'Silent Night', 'Golden Balls' and 'Jukebox' (on Elvis) – Vintage Nell concludes with a poignant description of her mother Lily's death in December 2004, and showcases the best work of this prodigiously talented writer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

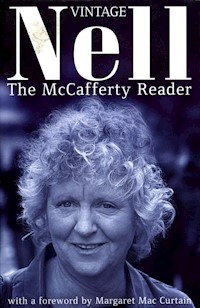

VINTAGE NELL

The McCafferty Reader

edited by Elgy Gillespie

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Heartfelt thanks to Irene Stevenson with Esther Murnane at TheIrishTimes library; to Cambridge University Library’s Ann Toseland; to Dermot Carroll and the Dublin City Library; and San Francisco copyeditors Anne Kirwan and Sarah Champion; also to Michael McLoughlin at Penguin Books for permission to use ‘Lily’.

PRODUCTION LAYOUT EDITOR CATHERINE BARRY A Dubliner born and bred, Catherine Barry has worked in publishing in areas of editorial, photo graphy and design for twenty years. She has worked and lived in Ireland, England and Australia, and now lives in San Francisco with her nine-year old son David.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

NELL McCAFFERTY

When I began journalism in 1970, there was a war in the North of Ireland, the root cause of which was the definition of that place as a Protestant state for a Protestant people, to which the ruling British government turned a blind eye. That war is over now, as is the one-party statelet, and the principle of a power-sharing government has been agreed. The IRA decommissioned its arsenal in September 2005, ending eight hundred years of armed struggle against Britain.

In 1970 the South was a mirror image of the North: a Catholic state for a Catholic people, actively encouraged by the Irish government. Thanks mainly to the war fought against patriarchy by feminists on the battleground of control of women’s bodies, the South is now governed by secular principles instead of religious.

In 2005 North and South are moving slowly together as one people on one island. This collection of articles is about what it felt like from 1970 onwards to live in both parts of Ireland. Sometimes it felt rotten—in the North you got shot at, in the South you got condemned.

Women were always at the bottom of both heaps. Male rulers felt that this was the natural order of things. Indeed, Irish Tánaiste and Minister for Finance, George Colley, was moved to warn females that members of the Irish women’s Liberation Movement were both ‘well-heeled and articulate’. He thought that was a bad thing for women to aspire to be. He was speaking after the feminists had imported birth control pills into the Republic, where possession of contraceptives was a criminal offence punishable by penal servitude.

If things were awful North and South, the fight to change the status quo was hugely enjoyable. It was my privilege as a journalist to meet the people who brought about change in their homes and towns and villages.

Sometimes I was censored or banned for what I wrote and broadcast. Still, we won, sisters and brothers. We changed our world for the better.

September2005

FOREWORD

MARGARET MAC CURTAIN

Nell McCafferty is unequalled in the extraordinary breadth and fearless candour she has brought to bear on controversial subjects we all needed to know about, to which she brought meaning and readability.

Let me give you a little flavour of her home place. In the tiny area of the Bogside where Nell was born, in the house that is still her home, lived or were born John Hume of the SDLP, Martin McGuinness and Mitchell McLoughlin of Sinn Féin, Councillor Mary Nelis, poet Seamus Deane, brilliant debater Eamonn McCann, Paddy Doherty of the Inner City Trust, peacemaker Brendan Duddy, and Nell herself. Nor is Nell ungenerous towards Rosemary Brown from the High Flats, who won the Eurovision for Ireland as Dana in 1970, and is still a very vocal presence in Ireland.

After Nell entered the sixties, she enrolled in Queen’s University Belfast as an Arts undergraduate, leaving behind a richly textured childhood and her family at Number 8 Beechwood Street, as well as the friendly neighbourhood to which she returned all her life where crime was negligible. Above them rose the walls surrounding the town centre and the Unionist stronghold, while everything outside the walls comprised the Bogside where the Catholics lived. There was the beach in Buncrana for summer swimming and family walks across the Border on Sunday mornings for cheaper food in the Donegal shops. Though she had serious illnesses as a child between the ages of six and ten, Nell made it effortlessly into Thornhill Grammar School, an all-girls convent school, and from there won a grant to Queen’s.

The most real people to her at Queen’s were not her teachers, nor the distinguished speakers that came to the English Lit. society of which she was secretary, but her contemporaries: Eamonn McCann, Austin Currie and John Taylor, while two years ahead of her were Deane, Hume and the songwriter Phil Coulter—all from Derry, and all household names in the decades to come, including herself.

Bernadette McAliskey, then Devlin, was to join that list and, much later, President Mary McAleese. When it comes to destiny, they were the first to embrace the future knowingly, and with desperate resolve. Between them all they created a radical new template for the political landscape of Ireland. Was it free education that made them exceptional, or was it the rising expectation of revolution that Marxist analysis offered, and which may have applied at home in Derry in the late sixties? There are still so many questions we continue to ask of this decade, for which Nell’s personal experiences inform our tentative answers. She compels us to recognize that we are far from revising or romanticizing that time.

From the time Donal Foley hired her in 1969, and gave her carte blanche to write up court cases in TheIrishTimes under the title ‘In the Eyes of the Law’ she has given us riveting vignettes—not just of the unsavoury sides of Irish life, but necessary wake-up calls about what was happening in situations where we desperately needed to be enlightened. Her piece ‘Consenting Adults’ offered a bleak comment on the humiliations of the early seventies before Mary Robinson and David Norris took up the cudgels on behalf of gay rights. She was called to Washington with a group of prestigious people from Northern Ireland that included Bishop Ned Daly of Derry, a family friend, and invited to testify before the House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs.

In 1980 her piece about the Armagh Women was published in TheIrishTimes, and women prisoners became an agonizing reality with the opening sentence of what the ‘dirty protest’ entailed. There was her coverage of the Kerry Babies inquiry for the IrishPress, later collected as AWomantoBlame, and PeggyDeery,AnIrishFamilyatWar, both published by Attic Press. Nell always published with small Irish publishers and Attic Press issued two more collections of her writing, TheBestofNell in 1984 and GoodnightSisters in 1986.

She was awarded Best Journalist of the Year by Hibernia early in her writing career, and in 1990 she received a Golden Globe award for her coverage of the World Cup soccer summer in Italy. Staffordshire University gave her an honorary doctorate alongside Mo Mowlam. Together with Saint Brigid, Grainuaile and Mary Robinson, she is one of the most cited references in TheFieldDay AnthologyofIrishWriting, and four of her essays appear in different sections of Field Day’s fifth volume: ‘Caoineadh Mná na hÉireann’ about the abortion debate, and ‘The Death of Ann Lovett,’ from InDublin. From Magill came ‘The Peace People at War’ in 1980, and the witty and satirical ‘Golden Balls’. Her SundayTribune and HotPressarticles from the late 1990s are republished here for the first time; as she approached her sixtieth birthday in 2004, Penguin Books gave us her autobiography, Nell, to which the moving Afterword, ‘Lily’, written about her mother’s death that December, appeared in the 2005 paperback edition, and concludes this anthology.

Poet Adrienne Rich has a phrase that illustrates Nell’s work: ‘To unlearn not to speak’ was the task that women’s liberationists applied to themselves and that June Levine and Nell describe so vividly in their accounts. Their efforts culminated in the episode of the Contraceptive Train from Belfast to Dublin on 22 May 1971, and the subsequent appearance of the lawbreakers on Irish television’s LateLateShow that night.

Nell has been teaching women ever since to unlearn the habit of holding their tongues—not easy for Irish women. Nell never flinched from verbal confrontation, and provided lessons in moral courage and truthfulness that many of us took to heart. In Nell she admits her fear of death as she cowered beside Burntollet Bridge, and her longing for the safety of home when caught in the panic of Bloody Sunday. Much later, she experienced the same feeling of panic when she covered the Siege of Sarajevo for the Dublin papers.

Hilda Tweedy remembers Nell’s activities in the early years of the Council for the Status of Women, which she chaired. In 1975 the Council hosted a series of events to mark the inauguration of International Women’s Year. Said Hilda, ‘Nell was unstoppable those years, she fearlessly protested against and exposed the government’s delay in implementing the EEC directive requiring member states to eliminate all discrimination on grounds of sex in the workplace. Equal pay was a burning issue.’

On the occasion of a state reception hosted by the then Minister for Labour in the National Gallery, Hilda Tweedy and several UN dignitaries were blocked by protesters in their limousine. After some delay, Nell’s curly head appeared through the open window beside the driver and Nell addressed Mrs Tweedy: ‘Hilda, we have no quarrel with you or your guests, it’s that so-and-so waiting to shake hands with you we want to rattle!’

One valuable insight I gained from Nell’s reflections and the feeling of defeat that many women experienced during the eighties was that, despite the divisiveness of the Pro-Life campaign for the Amendment, Irishwomen actually understood the meaning of sisterhood. Perhaps they understood it in the deepest sense, since women shared the hardships of imprisonment in Kilmainham during the civil war of 1922–3. This was palpable as the presidential election of 1990 loomed. I found that section of her book engrossing, and it brought back to me the fundraising, the way we tiptoed around feminist confrontational issues, the people we lobbied—and then the astounding consolation prize, the election of Mary Robinson after the woes of that decade.

With Nell, she chose to write an autobiography rather than a memoir—a chronology that moves the narrative along. Anyone looking for Nell at her most candid and most passionate will find her in her revealing account of the transforming relationship with another woman writer where she runs the gamut of honesty, true love, anger, loneliness, peevishness, desolation—all sorts of emotions.

It was a ‘first’ in Irish female autobiographical writing. What Fintan O’Toole remarked in TheIrishTimes about Nell’s critical writing holds true here too, that she radically broke new ground in Ireland. In a SundayTribune interview Anne-Marie Hourihan suggested that the great romance in Nell’s life had been her mother, and Nell did not dismiss the idea. Kathy Sheridan in TheIrishTimes also explored the mother-daughter theme.

But for me, the passion of Nell’s life has been Derry and its people, particularly her Bogside neighbours. She shared her grief with her readers as she read down the list of 3,630 people named as killed in LostLives, and she mourned for the remarkable place that is Derry City even as she enfolds it in her embrace.

With this new Lilliput Press collection of VintageNell, we congratulate her on a lifetime of journalism and of informed non-fiction, and we hope she will continue to enrich us with her critical thoughts on social issues. More than anything else we want for her the enjoyment of the writing she wishes to pursue for the rest of her life, and that she will achieve her expressed aim: ‘I will write until I die.’

MargaretMacCurtain,alsoknownasSisterBenvenuta,isanhistorianandmemberoftheDominicanSistersof Blackrock,Co.Dublin.

NUMBER SEVEN

THE IRISH TIMESJANUARY1970

An American journalist, writing for a newspaper in California, described Number 7 Wellington Street as ‘a humble shack in the Bogside.’ Dermie and his mother Mrs McClenaghan lived there until last Thursday night. Dermie is twenty-eight, an ex-dental mechanic turned accounts clerk. Since he left school he has always been on one committee or another—Legion of Mary, Boys Club, Labour Party, North-West Council of Social Services, Derry Citizens Action Committee—but he has never figured in the headlines. He is the boy with the beard from the Bogside.

The Californian was one of one hundred and twenty-seven journalists, photographers and TV crews who had to call at Dermie’s house during the August riots for a security pass, in the shape of an armband bearing the wearer’s name and number. An Egyptian journalist walked the Bogside for three days with ‘Winker 98’ printed on his armband courtesy of Dermie, who would not embarrass the fellow by asking him to repeat his unpronounceable name in his broken English.

Number 7 Wellington Street comprised two bedrooms, a sitting room, a kitchen, a scullery and an outside toilet. Dermie’s father once partitioned the scullery and installed a bath but the result was so cramped, Dermie said, that ‘you stepped out of the bath into the cooker.’ So they knocked down the partition and sold the bath to an enterprising farmer as a sheep dip. Like all houses in the Bogside, the rooms had a strategic use. If you were of unknown origin you were shown into the sitting room. When you entered the family circle you graduated to the kitchen. And when you were part of the furniture you went out to the scullery and buttered your own bread.

None of the doors ever closed properly. The kitchen door was secured by wedging a towel in it. To the uninitiated it must have seemed like a secret society. I remember one man to whom I handed the towel as he entered going out to the scullery and ceremoniously washing and drying his hands while we sat shivering in the draught.

Number 7 was a meeting place for the world and his wife. Mrs McClenaghan never asked you any questions. She met you at the door and said, ‘Aye, Dermie’s in, come on in surely,’ and then retired to the scullery to make tea, and sometimes in the aftermath when she was emptying ashtrays, she would hope we weren’t communists. Dr Abernethy, Governor of the Apprentice Boys, called there regularly to discuss horses with Dermie’s cattle-drover father.

Years ago, Ivan Cooper borrowed Mrs McClenaghan’s kitchen table and four chairs to use on a continental camping holiday and he and Dermie sold them in Paris for petrol. The Labour Party held its first meeting there around the same kitchen table and planned a housing march to Belfast that was later called off because of foot-and-mouth disease. A decision to defy the 5 October march was taken there.

Conor Cruise O’Brien, up from Dublin on a post-riot tour, was directed to Number 7 as ‘Bogside Headquarters.’ An enthusiastic Fianna Fáil minister gave Eamonn McCann fifty pounds as they stood in the scullery to use for ‘propaganda purposes’ after Taoiseach Jack Lynch’s broadcast—and Eamonn produced a classic ‘Barricades Bulletin’ carrying a front-page attack on the southern government. The famous photograph of Radio Free Derry’s ‘secret headquarters’ brought a furious letter from Dermie’s sister, married to a Free State garda, who recognized the picture of the Sacred Heart above the transmitter. The Dubliners gave a concert in the sitting room one Sunday morning and Ciaran kissed Mrs McClenaghan—but as Dermie later remarked, ‘Frank Sinatra’s never called.’

Number 7 was closed down on Thursday night courtesy of the Northern Ireland Housing Trust slum clearance scheme, and Brendan Hinds unscrewed the number off the door to give to Bernadette Devlin as a memento of her stay there. The removal was a short one across the street to a totally new environment—Glenfadda Park. The holy pictures were installed first with a wry comment from Dermie: ‘When the saints go marching in.’ The new address is somehow ludicrous, there being not one blade of grass in the concrete courtyard around which the flats are built. Dermie said they were moving out of little boxes into a filing cabinet. All the doors to the flats are closed and the place is curiously quiet. There is no street to scuffle your feet on or look up and down to ‘see what’s new.’ You can’t sit on the front windowsill and talk to the boys since there is a thirty-foot drop to the ground below. But in terms of comparative physical comfort the new house is a joy.

You can see it in little things—sugar bowl and milk jugs and bread slices on a plate. Formerly these things were kept in their original containers because sugar standing overnight in a bowl in a damp house becomes lumpy, and bread outside the wax wrapping paper becomes hard. In the spacious living room, you no longer have to eat in shifts if there are more than three people for a meal. In Wellington Street, the drop-leaf table always stayed folded because if you extended it properly someone would be sitting in the fireplace and Mrs McClenaghan couldn’t get in the door with the teapot. The new long living room seems vast by comparison. If you sit at the far end and watch television, Mrs McClenaghan says it’s like going to the pictures. She wants a loud hailer for when she ‘calls Dermie for his tea’.

The bathroom always evokes delight. The facecloth doesn’t have tea leaves and the soap doesn’t smell of onions. You don’t have to boil a kettle in the morning for hot water to wash your face, and despair if you put too much cold water in the basin afterwards. Now Dermie turns on hot and cold taps and whistles until the temperature of the water is just so.

Mrs McClenaghan bought a magnificent new carpet for the living room and doesn’t have to worry about rot seeping up from the damp floors under it. And if she still insists on covering it with the DerryJournal to protect it from muddy feet, it is only until the Commission has fixed up the new road outside.

A DAY I SPENT WITH PAISLEY

THE IRISH TIMESAPRIL1970

Alone in Crumlin Road Courthouse in Belfast at 9 am on Tuesday morning, Ian Paisley doggedly began his working day as he had thunderously begun his crowded open air meeting the previous night—in pursuit of law and order. He laid the complaints before the returning officer that a woman had been driving around the Bannside, stealing his postal votes.

He then spent an hour in the offices of the Puritan Printing Company Limited with his youthful election agent, the Reverend Beggs, a charming clerical version of Anthony Perkins. At 11 am he appeared in the village of Ahoghill, Bannside. His local contact man scuttled ahead of him, knocking on doors, pointing back to the big man. Scrubbed and smiling, solid in the drizzling rain, Paisley moves steadily from house to house, forthrightly introducing himself as a Protestant Unionist candidate. ‘And here’s some literature for you!’

He filled the doorway, hands on either side of it, leaning in, looking down, the brief seconds large with his presence. I asked a woman why she was voting for him, and she was astonished at my ignorance: ‘The Lord’s Word must be spread.’ What did she want from him politically?

‘Material things don’t matter when we’re before our Maker.’ In slum dwellings of the main street, the occupants seize him with delight. ‘Thon Minford never came this far yesterday. You speak up for us, Doctor Paisley.’

At 1 pm, the village covered, Paisley stepped into his car and drove off. A covered jeep, little Union Jacks on the bonnet and Scots céilí music coming lightly from the amplifier followed, with me and my taxi behind. We lost them at a country crossroads. Later we found the parked jeep and Wesley the puzzled driver beside it. A petrol pump owner from Lisburn, he didn’t know the area. ‘You couldn’t keep up with the Reverend. I never seen such a busy man.’

He talks matter of factly to me about the fires of hell. He had been saved from the paths of darkness five years ago. ‘And I attend the Doctor’s church three times a week now. He’s a real man of God.’

We decided to go to Ballymena to election headquarters, where Paisley himself answered the door, a sandwich stuck in his mouth. ‘Come on in Wesley, we’ve only a couple of minutes.’ I stood damply behind, dying for a cup of tea, and he closed the door in my face. My taxi driver went away for lunch and never came back. I felt like a lonely little Republican. Wesley came out and invited me to sit in the jeep. He was very friendly and said I could travel around in the jeep with him. Paisley arrived and decided not to use the car as he was going into farming country. He unsmilingly told me that to be honest he would rather I get myself other transport.

Wesley blushed. I stood on the street as I remembered the services I had attended at the Doctor’s church on Raven-hill Road. An amazingly personal and personable man, Ian Paisley preached an impersonal sermon: ‘Salvation is between Christ and you. It will not come through the Roman Church or the Protestant Church or my Church. Salvation comes through Jesus and the Bible.’

From the austerity of the Lord’s Word we were drawn quickly back to the intimacy of the pulpit politician on the Ulster scene. He leaned forward, grinning, arms on the pulpit, as the country’s leaders are lashed, dismissed and belittled with a joke. The eyes close, the head is bowed, and then up again to Christ Crucified. We sing tunefully of Jesus, accompanied by an organ, and the man beside me smiles widely, eyes bright, singing to the Saviour. He gives me a Polo mint. The basket is passed, filled gladly with money, and then it’s time to be saved. Some people go to the front of the church returning to the Lord, and then pass on to a back room where Dr Paisley will later talk to them.

* * *

The service over, the organ pumps us out; many remain behind, lingering in the aisles or in the benches, chatting in groups, hovering near the inner rooms where the Doctor receives his parishioners. He moves quickly to and fro, talking, laughing, giving directions. A boy is going to London to look for a job and Paisley gives him the address of a colleague there. Then he says, ‘Wait a minute,’ rings up the colleague and tells him to expect the boy off the boat train tomorrow evening. He shakes the boy’s hand ‘God bless you son, drop us a line, goodbye.’ Then he puts his arm around a young couple who want to get married. He sweeps them into his office, joking about their impatience. He’s a big man with a big voice, but he leans quietly over an old woman in the corner, chatting to her while we stand around waiting to get a word with him, a smile from him, and we agree that he is a good man of God.

It is 10 pm, ninety minutes after the end of the service, but people are still in the church and Mrs Paisley and her children move amongst them. Paisley is in his office on the phone discussing Election Day caravans with his brother-in-law and men are queuing up to sign on as election workers and to offer cars.

I caught up with Dr Paisley in Cloughmills, a quiet country village. The men in the pubs say they are not going to vote. ‘We’re all right here, without them cowboys from Belfast, they never came down here before except that noo they’re afeared. Thon Minford can’t talk.’

They chuckle when I ask about Paisley. ‘He won’t be coming in here for a drink.’ What do they think of McHugh? They thought it’s a pity about him. They talked about the moon shot and Leeds United.

Paisley was going the rounds of the doors, apologizing for interrupting at suppertime. He spoke to a worried woman whose mother lived alone in Grace Hill and left her laughing. Further up the street a man shouted at the sight of him and invited him in. He took off his Cossack hat, wiped his shoes, disappeared inside. His agent was worried about the time. ‘The Doc hasn’t had a cup of tea since dinner hour.’ It was still raining. I asked Wesley to play ‘The Sash’ to cheer us all up and the agent told me that I’d rather have ‘The Soldier’s Song.’

Paisley continued his relentless rounds, but at five to eight he decided to leave, jumped into the jeep, then jumped out again to lock a garden gate. No, he told a policeman, he would not be going to Dunlow. ‘Let the Prime Minister speak there.’ And he drove off to the first of two open-air meetings twenty miles away.

In Wood Green the crowds gathered for a night’s craic. They pour out of cars, tapping their toes to the Lambeg beat. Massive Union Jacks wave in the breeze. At the far end of the village a fife-and-drum band plays ‘No Surrender’ and Paisley, sash across his chest, smiles across his face, comes striding in. We’re dancing with delight, we’re people now, and the men talk of B Specials, Craig, and the alien master Chichester-Clark. ‘Sure, he won’t be able to do much, he’s only one man, but he’ll tell them what we’re thinking, he won’t let them away with things any more.’

Paisley gives a rousing speech and promises full use of the parliamentary privilege. He quotes a number of houses without water. ‘But nothing,’ he says ‘can stop the rising tide of Loyalist opinion.’ He answers every question afterwards.

‘Chichester-Clark says you’re not British, Doctor Paisley.’ Paisley snorts dismissively. ‘Isn’t that ridiculous?’ and we laugh, and know they’ll tell any amount of lies on him, they’re that frightened. He steps down in amongst the crowd. His mother sits inside the jeep, waiting on her son to go to a local house for tea. He is very open and intimate and the men stand more proud and convinced after talking to him, and the women cluster around him, nodding their heads and giving him little white envelopes. He thanks them. He is confident and bulky in the dark and quotes the Bible and it is very reassuring. He sends you away with a joke and you aren’t afraid any more. You can’t be wrong if you’re on the side of God and Ulster, with this big strong man in front of you. No one will sneer at you when the Reverend is around.

And that’s Ian Paisley, Protestant preacher man, possible and improbable MP. For a wrathful God and an orderly Ulster where all the men are sinners and the wages of sin are death. In Christ Crucified is Salvation. Then he grins and you don’t feel so bad about it.

OUR STREET

THE IRISH TIMESMAY1970

Once everybody in our street used to vote for Eddie McAteer and sing ‘Seán South’ and hate the Corporation and enjoy the bands on the Twelfth, and Belfast was a place where you might get work, and if you were a Protestant you might get work, and if you were a Protestant you would somehow be better off, but you hadn’t as much chance of getting to Heaven; and we wished for a United Ireland, although Dublin in the South was a foreign place, and if you became a teacher you were somebody; at least you were sure of always getting a job.

Last year our street split—fanatically—between Eddie McAteer, John Hume and Eamonn McCann, and the more progressive among us agreed that if Derry seceded to the South, Eddie would lead the charge across the bridge, waving his family allowance book; and who wanted to be a teacher when Du Pont paid thirty pounds a week, and Dublin didn’t help us much in August and we hated Stormont, and we heard of the slums in Fountain Street and we welcomed the British troops, and we sang ‘We Shall Overcome.’

There are spinsters in our street who broke their hearts and they stayed at home because they couldn’t marry a Protestant. But several young people in our street have now made mixed marriages, although significantly they all married outside the parish and then moved out of town.

There used to be big nights in our street when a long-lost relative came home from America, and the women would sip sherry and the men would drink stout, and we would lean over the banisters and listen to them singing ‘The Isle of Innisfree’ as we thought of John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, and afterwards they would go out into the street and bang pots and pans and sing ‘Auld Lang Syne’. My aunt used to tell me how she shovelled coal into the boilers in the States, and I couldn’t believe it, looking at her fur coat. I preferred the story of Captain Bounty who made his fortune in coconuts; and even though he kissed her toes, my aunt preferred to marry her Joe from Derry who worked on the railroad.

Some things, it seems, never change. In 1835 the Ordnance Survey of Derry recorded that, ‘no calculation can be made of the large sums sent to residents of Derry from abroad … no chance of place or habit interfere with the ties of consanguinity which bind the Irish emigrant to those whom he had apparently deserted.’ But we don’t have so many big nights any more. There are charter flights to America, only hours away, and we go and visit them.

Our street has a communal telephone and a communal car. The initial advantage for the telephone owner of not stirring from the fireside has rebounded somewhat, since he is continually running up and down the street saying ‘Maggie has just phoned from England, and wants to talk to you,’ or answering the door to a neighbour who wants to phone Jimmy in Scotland. The communal car belongs to the neighbour who takes you to the hospital when you’ve broken your leg, or takes your friend home on a very rainy night. The car owner is invariably described as being ‘wild obliging.’

Our street has a communal shoulder, Mrs Barber, on whom one leans in times of stress, a communal source of miraculous relics, Mrs Doran; one for every illness, a communalgenealogist, Ettie, who knows everybody and their ancestors and descendants, a communal handyman George, who can fix things and paint your house, a communal mother, mine, who gives out pieces of bread and jam, a communal seamstress, Tessie, who always has thread, and a communal source of cheap shirts, Annie, who works in the factory. We have a communal midwife, Nurse McBrearty, who gets babies direct from God, cutting out the middleman and transport expenses. Thus, I only cost my mother five pounds.

Mary-across-the-street has a lot of children and has to get up early, so she is our communal alarm clock, and Brigid-up-the-street keeps the keys and pays the debts of neighbours who go away on holiday. We even have a communal joke—on the day when pooled resources could not spell diarrhoea, Mamie sent a note to the teacher saying, ‘wee John, big shite.’

Our street has a communal centre outside Ettie’s door, where the women gather to chat after lunch hour on all but the worst days. They sit on chairs, on mats, or lean against the wall. If you approach Ettie’s door from the foot of the street, your ancestry is established before you’ve passed the first house. Two more doors and we know your man’s job and the number of your children. By the fifth door, your skeleton walks beside you, within earshot your health is questioned, and as you arrive we ask you ‘What’s new?’

The men in our street meet round the corner at night and out of sight in George the bookie’s shed. We have never found out what really goes on there. But we are working on it.

Since it was first built, only three houses in our street have changed tenancy. We acquired snob status when permission to convert a house into a sweetshop was refused on the grounds that we were a residential area. Since the arrival of a new neighbour Gerald, a male nurse in a nerves clinic, we have discovered that we suffer now from acute depression as opposed to being simply fed up.

In our street there was no surprise when Patsy completed six months training as an apprentice plumber at the Government Training Centre, and then did six months on the dole before catching the boat to England. There is relief about the new houses, and cynicism about the absence of new jobs. There are great memories of last year and worries about this year. Our street doesn’t really want to go back on the streets; but the men don’t want to go back onto the street corner.

HER MAJESTY’S DERRY

THE IRISH TIMESDECEMBER1970

Because of unemployment and subsequent emigration there is a noticeable absence in Derry of bachelors in their early twenties. Consequently, those girls who have not yet ‘got a man’ hail the arrival of the forces enthusiastically and it is a pleasure to be wined and dined without regard to the ‘Buroo Budget’ or Social Welfare.

Derry is famed as a run-ashore port. The pubs are many and the girls are glad. Americans come first in the marriage stakes, but the arrival of the six-foot Grenadier Guards has somewhat evened things up. For the really discerning there are the RAF officers at Ballykelly, and the difficulties of distance, transport, and entry to their social club seem to be but minor deterrents.

The British sailor fared badly during the war years; he had nothing to offer but his pale maleness, which at that time was superabundant, while the Canadians had silk stockings and the Americans had dollars. But after the war, when the steep rise in illegitimate births was attributed mainly to the Americans, the British forces became rather more acceptable.

That the British naval presence has never aroused anti-British feelings in what is generally regarded as a Nationalist town is due to two factors. The naval base is situated across the river on the fringe of the Waterside and thus is outside the daily life of the city. When the sailors ‘come ashore’ they normally don civilian clothes. More importantly perhaps, the Navy has never been used to quell any rebellion or mix in the internal affairs of the town. The sailor comes, drinks, dances, and goes.

The British Army on the other hand is pursuing a shaky course. They arrived last August as saviours of the beleaguered Bogsiders. In their ‘hearts and minds’ campaign they undertook to provide recreational facilities for the youth of the city: a display of interest and attempt at integration which none of the services had ever shown before. But all this is continually offset on the Catholic side by the harsh semi-curfews they have imposed on Bogside residents every time the temperature has risen, and on the Protestant side by the fact they have replaced RUC control of the city.

MY MOTHER’S MONEY

THE IRISH TIMESMARCH1971

The way my mother sees it, ‘they’ have her beaten every time. She sat with her grocery book on Saturday night and worked out her weekly bill. The shopkeeper had marked the goods in ‘English’ prices, as she calls them; but the total, line by line, was marked in decimals.

My mother calculated, with pencil, glasses, currency converter and the blank edges of TheBelfastTelegraph that she was being diddled to the tune of a halfpenny a line, but by the end of the page she was out tenpence, in pounds, shillings and pence, that is.

Then she added the total up in ‘English’ money. The three pounds eighteen was easy enough. No diddling there. And on the extra threepence, she lost only three-fifths of a penny. So my mother wants her total in ‘English’ money from now on, and she’ll convert it herself.

Then there’s the coalman. He charges her nineteen and ninepence per bag of coal. If she gives him a pound, he will give her a penny change. Thus, she loses a ha’pence per bag. He told her that wouldn’t break her. No, she pointed out, but with five hundred customers, those extra halfpennies will make him richer to the tune of one pound tenpence per week.

‘So what do you want me to do?’ says he, ‘Divide a bag of extra coal among five hundred customers?’ My mother sat in the house on Saturday night and thought over the problem.