18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

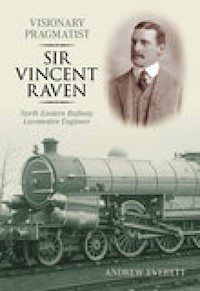

When the "Railway Magazine" of January 2000 published the results of its Millennium Poll, Sir Vincent Raven gained a 42nd place, along with Thomas Newcomen and Arthur Peppercorn. This is the biography of this engineer, illustrated with contemporary archive photographs, portraits and ephemera.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Lorraine and Madie of North Road Study Centre in Darlington; to the many library staffs of the universities of Newcastle and Northumbria libraries, to Newcastle Discovery (Tyne and Wear Archive Service), Durham Record Office, the National Archives (UK) and New South Wales (NSW) National Archives and NSW Government Library; of the Public Libraries at Darlington, Oswestry, York, Gateshead, Newcastle in UK and Blacktown and Baulkham Hills (NSW) for their help to me; to the Public Libraries staff at Felixstowe, Winchester and Basingstoke for their help by phone and letter; to staff of the National Railway Museum at York for their time and help in gaining access to their archival collections, to the archivists of ICE, IMechE and Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE) for their positive help with their material both by post and personally; to the two librarians of Aldenham School for the book on the school and further Raven family information, to the archivists at Polam School, Darlington, and of Uppingham School, Rutland; to Mrs Myers, the president of Darlington Townswomen’s Guild; to the owner of Old Hall, Hurworth; to the secretaries of Felixstowe Ferry and Lydney Hall Golf Clubs for their helpful suggestions; to Roger AC Hennessey and other members of the Stephenson Locomotive Society; to Geoffrey Hughes and members of the Gresley Society; to members of the Railway Correspondence and Travel Society and to Chris Wolstenholmes, librarian, and to many other members of North Eastern Railway Association for their encouragement; to Ross Verdich and members of the Australian Railway History Society in Sydney and Newcastle (NSW); to a large number of other railway and history societies I have contacted and spoken to about Raven for their encouragement and suggestions; to descendants of Raven’s family still living for their interest, courtesy and correspondence; to Malcolm Middleton for information on Alpine Cottage and Bowls Club; to my son Paul and daughter Catherine for their encouragement and advice; and lastly, to my wife Mary, for her patience and support during the writing of this book.

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Abbreviations

I

Family Background and Early Life (1858–1875)

II

Starting with the North Eastern Railway (1875–1882)

III

Progressing in his Career (1882–1893)

IV

Move to Darlington (1893–1901)

V

Assistant Chief Mechanical Engineer (1902–1910)

VI

CME to NER (1910–1912)

VII

Developing a Civic Persona (1913−1914)

VIII

War Effort and Knighthood (1914–1918)

IX

Return from War (1919–1921)

X

Farewell to NER (1922–1923)

XI

Commissions Royal and Otherwise (1923–1924)

XII

Raven’s Last Years (1925–1934)

Postscript: Evaluation of Raven’s Achievements

Appendix I

Appendix II

Bibliography

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

When TheRailway Magazine of January 2000 published the results of its Millennium Poll, Sir Vincent Raven gained forty-second place, along with Thomas Newcomen and Arthur Peppercorn. He, like them, usually merits little more than a brief mention in railway history books, yet in many ways he was much more than a typical man of his time. In appearance, he bears quite a striking resemblance to his contemporaries in music, Sir Hubert Parry and Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934), the latter being Raven’s almost exact contemporary. Ironically, like Parry, Raven lost out to a younger and more famous successor, namely Herbert Nigel Gresley (ranked third in the Millennium Poll). There is a solidity and style about the work of both the older men, which came to be eclipsed in the public mind by the more famous creations of the younger men. This is an attempt at a reappraisal.

Much of Raven’s steam and electric locomotive-building activity has been charted in a piecemeal pattern without seeking to make a cohesive biographical narrative of it or place it in the context of his life and times except briefly, tentatively and unsatisfactorily in obituaries and in other incomplete digests about him, such as the ‘candidate circulars’ for Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) and Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE).

The title of the book, Visionary Pragmatist, was chosen because Raven used the North Eastern Railway Co. (NER) frameworks to develop his career in quite a traditional and practical way both as a junior and senior company servant. Yet he became convinced at the end that rail electrification was the most practical way forward for the future, being both a complementary and an alternative means to the development of steam rail locomotion.

Facts about his own family both before and after his lifetime are sparse. Raven, like other railway notables in the last years of the nineteenth century, had a clerical father. His wife and his five brothers and four sisters all remain shadowy figures with only a few facts known. His two sons, and his grandson and granddaughter, Michael Litchfield and Mary Gifford Taylor, emerge a little more from the shadows as does his daughter, Edith Guendolen, because of her relationship to Edward Thompson. While there is much discoverable material about what he did, especially about his locomotives and how successful they were deemed to be and dates available about his professional, civic and committee life, it has been much more difficult to learn about what kind of the character the man was, whether as pupil, apprentice, husband, father, friend, engineering colleague, successful engineer and senior manager in a profitable company or as elder statesman knowing about railway matters. Raven’s extant writings, the conference papers and reports for NER, plus newspaper reports of what he said, are couched in language carefully worked out for the occasion and only give occasional glimmers of what motivated him at work.

His life falls into seven distinct phases. Firstly, there is his childhood and schooling. This leads naturally to a second phase – his choice of apprenticeship. Here, Raven seems to have decided early on his own career pattern rather than that of his father’s family, going to Cambridge University. Instead, he chose an apprenticeship in a career in engineering with the railways of the North East of England. A third phase followed with his early career as employee of the firm. It included his marriage and fatherhood as well as his climb up the ranks under four different locomotive superintendents, gradually moving to the forefront of a design-and-build team.

A fourth phase is marked by his becoming chief mechanical engineer and his further moves into the civic life of Darlington and the marriages of his daughters. This period was interrupted by a fifth phase as a result of the First World War, namely his work for the Ministry of Munitions and the Admiralty. He now exceeded the social achievements of his Raven ancestors and that of his children and grandchildren in gaining a knighthood, very much as a result of his own efforts.

A return to NER and a dedication to electrifying the railways and developing his Pacific characterises a sixth phase − his last three years with NER. A seventh and final phase is ushered in by his retirement from NER, which left him time to become both a railway guru as well as an electrification Cassandra, to do a lot of committee work, investigations and subsequent reports. It is a story of a largely self-educated man making the most of his talents in a chosen field of activity.

How he related to the many people, who met him over the years can be inferred fitfully from the evidence available. His religious and political opinions and his social objectives are not easy to uncover. For instance, his membership at the local Masonic Lodge probably served as a vehicle for meeting local people of consequence or influence. His church attendance was for main life events, rather than devotion, although there is a deep underlying honesty in his approach to his work and to how he related to others.

The family tree material has been gleaned from a variety of sources, e.g. from the International Genealogical Index, Cambridge University Alumni and Registrar General’s Office − Free Births, Marriages and Death Project and War Graves Commission. For consistency, the variants of his wife’s forename of Gifford and her surname Crichton, e.g. Giffard or Chrichton, have not been used.

Family trees and tables included in the book have been drawn up by the author. Photographs taken by the author show what is currently available from Raven’s time, while archive photographs come from as near contemporary material as possible.

ABBREVIATIONS

AGM

Annual General Meeting

ARLE

Association of Railway Locomotive Engineers

ASRS

Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants

CE

Chief Engineer

CME

Chief Mechanical Engineer

CR

Caledonian Railway

EBR

East Bengal Railway

EIR

East India Railway

EE

Electrical Engineer

GCR

Great Central Railway

GER

Great Eastern Railway

GIPR

Great Indian Peninsular Railway

GM

General Manager

GNR

Great Northern Railway

GS&WR

Great South & Western Railway

GWR

Great Western Railway

H&BR

Hull & Barnsley Railway

ICE

Institution of Civil Engineers

IEE

Institution of Electrical Engineers

IMechE

Institution of Mechanical Engineers

LB&SCR

London Brighton & South Coast Railway

LN

Leeds Northern Railway

L&NER

London & North Eastern Railway

L&NWR

London & North Western Railway

LS

Locomotive Superintendent

L&SWR

London & South Western Railway

L&YR

Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway

M&M

Merz & McLellan

MR

Midland Railway

NBR

North British Railway

NECIE&S

North East Coast Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders

NER

North Eastern Railway

National Archives former Public Record Office (PRO)

RCA

Railway Companies Association

RE

Royal Engineers

ROD

Railway Operating Department

SD&R

Stockton & Darlington Railway

SE&CR

South East & Chatham Railway

SR

Southern Railway

WBR

West Bengal Railway

YN&BR

York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway

Y&NMR

York & North Midland Railway

Note on locomotive wheel arrangement

I

FAMILY BACKGROUND AND EARLY LIFE (1858–1875)

Over many centuries, branches of the Raven family have become widespread throughout England and in Northern Europe, even if not very numerous. Revd Vincent’s branch came originally from Norwich. Raven’s great-great-grandfather was Henry Raven of Norwich, who married Sarah Baldwin at St Giles, Norwich, in 1781. His son, Henry Baldwin (noted as working at the Treasury), was baptised in St Peter Mancroft, Norwich, on 2 December 1781. He eventually moved to London. There he married Mary Ann Litchfield (whence came Raven’s middle name). She was from a London family (her father’s name was Vincent). Henry died in December 1872 aged about ninety-one. There were three children of the marriage, Revd Vincent (Sir Vincent’s father), Sarah Baldwin and Revd James Dillon. The two sons both went to Cambridge University and then followed a clerical career.

James Dillon, the younger son, was born on 12 November 1823. He followed a similar career to Vincent as a priest of the Church of England. After attending St Peter’s Grammar School, Pimlico, London, he matriculated at Michaelmas in 1838, entered St John’s College, Cambridge, on 18 January 1839, and quickly transferred on 21 January to Magdalen, where his brother was completing his MA. Graduating as a BA in 1842, he was ordained deacon in Chester on 18 December, working in a number of places, including as a curate at St Mary’s Bolton, Lancashire, from 1842−1824. After ordination in 1844 and gaining his MA at Magdalen in 1845, he worked in the Home Counties. After 1858, he lived at St John’s Lodge, St John’s Road, Eastbourne, and was living there in 18811 with his wife, Mary Anne (born in 1830). He had moved to several rural parishes in Home Counties from 1852−1858, finally settling at Eastbourne as a clergyman. There were no children at home in 1881 (if any had been born to the couple). However, he was a clergyman without a benefice, making his living as a schoolmaster to ten boys between the ages of seven and eleven from the northern Home Counties and Midlands. James Dillon later lived elsewhere on the south coast, dying at Shanklin on the Isle of Wight on 24 March 1900.

Sarah Baldwin was born at Cadogan Square, London, on 24 November 1922, but remained single; after Revd Vincent’s death, Anne Rainbow went to live with her sister-in-law in Chelsea.2

Vincent, the older brother, was educated at King College, London. On 23 April 1833, he matriculated, joining Magdalen College, one of the smaller Cambridge Colleges in Michaelmas 1833 as ‘sizar’. Linked originally with East Anglian abbeys, Magdalen is one of the more ancient university foundations, dating back to the 1470s. Its most famous past alumnus was Samuel Pepys.

Vincent went on to obtain his BA (10th Wrangler) in 1836, becoming a fellow the same year. As a fellow, he is likely to have had contact with nineteen-year-old Charles Kingsley, Magdalen’s most celebrated nineteenth-century alumnus, who came to Magdalen in 1838. Raven was ordained deacon at nearby Ely and priest of the Church of England in 1839, becoming an MA at Magdalene in 1840. He then served as curate in London from 1840−1843, returning to the academic life at Cambridge, becoming dean at Magdalen between 1844 and 1846. He took up the post of tutor between 1846 and 1853, serving as president from 1850−1853. As the tutorship at Magdalen was a bachelor one, Revd Vincent Raven had had to resign his fellowship and tutor’s post when he decided to marry in 1853 Anne Jemima Rainbow, daughter of John Rainbow (a variant of Raimbaud) from London. He was fortunate that Magdalen could provide him with a benefice, that of the rector of All Saint’s, Great Fransham. It meant that he returned to the county from which his father’s family had come.

Great Fransham is a small, very scattered village, lying in fields in the open North Norfolk countryside. Despite hedges and trees, it is open to winds and rain, especially in winter. It lies about six miles east–north–east of Swaffham, down a lane a mile from the King’s Lynn to Norwich road, eventually petering out after the station building. It had 391 inhabitants in the 1841 Census and had only relatively recently been connected to the King’s Lynn and East Dereham Railway, built from 1846−1848 by a station to the north of the village. By 1854, it was served by four passenger trains and one goods train each way daily, despite having only seventy-four houses, a reduction to a population of 319.

The church of All Saints is rather piecemeal in style and run down in appearance, and has some Perpendicular features with a south arcade of four bays and a square tower with a short spire; its nave was restored in 1878, during Raven’s time as rector.3

The Rectory lies a few hundred yards from the church. It is approached by a short drive to the two-storeyed house. It has a Georgian front and door case, added in the early 1800s to an earlier farmhouse with its lower ceilings and crossbeams, still to be seen in kitchen, larders and storage rooms to the rear. Being in the gift of Magdalen College, it had sixty-three acres of glebe and a yearly rent of £552 in lieu of tithes. Charles Reynolds, the previous rector, had built a school, which continued to be chiefly supported by Revd Raven.4

All Saints, Great Fransham, where Raven’s father was rector from 1854−1887.

Raven’s ancestors and siblings.

The Rectory where Raven and his six brothers and three sisters were born.

Arms of the Worshipful Co. of Brewers, whose Trust Fund has supported Aldenham School since 1576. They share the same motto.

As a couple, the Ravens were prolific, producing seven sons and three daughters all born at the Rectory. Besides the family, the Rectory supported a governess for the children, a cook and a housemaid. Apart from his domestic role as paterfamilias Revd Vincent, his spiritual duties as rural parson and educational ones as supporter of the local school and its teachers, he spent his leisure time in providing his church with a finely carved and detailed pew bench, lectern and altar table in a quite elaborate ecclesiological Puginesque style, rather at variance with Low Church practice. During the autumn of 1887, Gertrude Jane married Arthur Perks in the area. When Revd Vincent died on 12 December 1887, the rest of the family had moved elsewhere out of Norfolk.5

Raven himself was born on 3 December 1858.6 Following upper- and middle-class custom, Vincent was sent to preparatory boarding school at Brighton, probably when he was about seven years old. He may have had some contact with his uncle in nearby Eastbourne during that time. He then followed his older brother to Aldenham School in Hertfordshire from 1872 to 1876.

Henry Baldwin, Raven’s oldest brother, was born on 17 March 1856. Five of the brothers, Henry Baldwin, Raven himself, Hubert, Ernest Woodhouse and Frederick Rainbow were all educated at Aldenham School, Hertfordshire, from 1872 to 1881. Henry Baldwin was there from 1870 to 1876. He was a good enough sportsman to play on the school football and cricket eleven in 1876.

Aldenham School buildings in 1867, viewed from Alfred Leeman, the headmaster’s, garden.

Aldenham was a good private grammar school, where the spirit was High Tory and solidly traditional Church of England. It is sited about five miles south-west of St Albans, where it had originally been set up in 1549, having been endowed by Richard Platt, a Freeman of the Brewer’s Co. It had lingered on through three centuries until taken in hand by new headmaster Alfred Leeman in 1843. It normally had about seventy-two pupils with a class average of twelve. Fees from 1873 were £15 to £25 a year for tuition, with boarding fees not exceeding, £65.7 Sons of the middle-class men, such as clergy, doctors, lawyers and farmers, would come from as far away as Ireland Northumberland, Kent and Cornwall to a school where the food was adequate, but home comforts rather rudimentary.8

Alfred Leeman was headmaster, a Cambridge man to the core, who actively recruited other Cambridge graduates to his staff, and also anticipated that his more able pupils would gain entrance to Cambridge and graduate there. Born in London on 14 December 1816, Leeman had attended Louth School, and matriculated in 1835 for Cambridge, gaining his BA in 1839 and MA in 1842. It is possible he met Revd Vincent and Revd James Raven there. Leeman was ordained deacon at Winchester on 11 July 1841, but did not immediately continue into Church of England priesthood. Instead he took up a career in education for the next forty-two years. A second master at Oakham School from 1839−1841, he became headmaster at St Paul’s School, Southsea, in 1841−1843, before moving to Aldenham, remaining there until 1876 during which time he set it on its feet. Revd Vincent Raven may have come to know of Leeman’s reputation as headmaster at Aldenham.

Of average height and thickset, and not very careful about his dress, Leeman had dark greying hair and whiskers, which framed a red face. Despite his easy manner, keen sense of humour and mild eccentricity, he showed that he was no mere figurehead. He could be very vocal in his representations to the governors about the well-being of both staff and boys. He taught the senior pupils of the school Latin and Greek. The pupils, who called him ‘the Gaffer’ did Horace’s Odes and Satires and a Greek play using cribs, year in and out.9 He patrolled the school in carpet slippers, wearing a tall hat, accompanied by his little dog ‘Tan’, who sometimes barked to give the lads warning of the Gaffer’s approach, if they had not heard him humming to himself and so were caught in doing something they should not have been doing. Punishment was swiftly meted out with the cane he carried.1011

Presumably Raven started at Aldenham in January 1872,12 the year being divided into two halves − a term about twenty-five to twenty-six weeks from January to June with an Easter break of seven to ten days (except for those who lived 100−200 miles from home, who continued to board) − and a twenty-week term from August to December. Prior to starting the school, there was an old ritual of inspection by the school governors to undergo for all prospective pupils (including Henry and his brother Vincent and later his other brothers). They were required to attend Old Hall of the Worshipful Co. of Brewers, Aldermanbury, near Moorgate. The candidates were asked one or two questions, given a glass with port in it and a big sweet bun, after which they were approved as pupils.13 A pupil could be paid for totally privately or possibly be a foundationer. A proportion of the boys were partly funded by the Brewer’s Co., those from the local parish of Aldenham or sons of the Freemen of the Brewer’s Co. for which parents could pay £20 to become freemen.

The school was in the grammar school tradition, preparing its graduate material pupils for going on to Cambridge, the likely perceived goal for the Raven’s boys both at home and at school. Indeed, fostering a ‘Cambridge’ atmosphere was part of Leeman’s educational plan, a scheme he furthered by appointing young Cambridge graduates to his teaching staff.

There was ‘Mac’, i.e. Herbert James McGill, whose classes read Vergil and Xenophon, but who was a keen naturalist; ‘Robar’, i.e. Charles Robert, a kindly, genial man, taught the junior classes and did elementary work in general. ‘Both McGill and Roberts were painstaking and energetic, and did their best to instil scholarship into us… and R. Stevelly, who ground Mathematics into us all... The Mathematical instruction was invariably of high class, and well carried out.’14 Apart from learning to read and write good English, Raven probably benefited most from this teacher. Monsieur Quesnel came in to teach French and Messrs Gilbert and Lupton, music and drawing. The two worst features of the school according to the accounts were the dull food (although this was relieved by what a boy had in his own tuck-box, such as Fry’s Cocoa and home-made jam) and above all, the quite execrable state of the toilets.

As can be seen, the curriculum was narrowly academic. Science subjects, the mechanical skills and the higher mathematics to promote them at an advanced level were missing. In this respect, the education Raven received was of little use to a future railway engineer, although typical enough for its time. A report from the Schools Inquiry Commission of 1869 noted that the instruction at the school presented was Classical: no scholars learn bookkeeping, mensuration, physics, chemistry or natural history.15 It would take some time after Leeman retired and the older Raven boys had left before these were introduced into Aldenham’s curriculum.

Raven and his brothers followed a daily timetable, which operated most week days, but was suspended on Sundays, where there was attendance at local church. Prayers were said in the morning and early afternoon or in school if the weather was too bad. On 5 November, Guy Fawkes’ Day, there was a school holiday.

Times

Activity

6.30

Rise (2 hours allowed for dressing)

7.00

Roll call

7.00 - 8.00

Lessons

8.00

Breakfast, i.e. bread, butter and tea

9.00 - 10.50

Lessons, introduced by daily prayers

11.00 - 12.00

Lessons, followed by a hasty game of cricket

1.30

Dinner of meat, potatoes, served with beer, then pudding or cheese

2.00 - 4.00

Lessons (except for Wednesdays and Saturdays)

5.00

Tea (with bread and butter)

6.00 - 7.00

Lessons - prep(aration), finished with prayers

7.30

Supper as for breakfast

Later for seniors

Supper of bread, cheese and beer

Daily timetable at Aldenham School, 1870s.

Aldenham, in the light of Raven’s future career, would continue to give him a surface polish and self-confidence, an ability to write clear correct English and at least a start in mathematical principles. From the point of view of religious belief, Raven would not be notable as a devout member of the Church of England, but later seem to attend more as a part of social custom, for instance for his own marriage and that of his children. With regard to railways, he could well have read about such matters at home and school, but his formal education did not give him a theoretical or practical basis for an engineering career with a railway company. Both Raven and his brother Henry left Aldenham by 1876.

The time spent here stood his brother Henry in better stead. A good enough sportsman to play on the school football and cricket eleven in 1876 (there is no mention of Raven himself being picked), he left Aldenham, having possibly gained an Exhibition grant of £40 from the school, and followed the footsteps of his father, uncle, other Aldenham teachers and pupils by going to Sydney College, Cambridge, in 1880. He was resident at 25 Doughty Street, St Pancras, in 1881, lodging with an elderly couple, Robert and Sarah Price, possibly on Easter holiday or on some kind of work experience there before graduating as a BA in 1883. He became a solicitor with Hare & Co., the firm of solicitors to the ‘Treasury’, where his namesake grandfather had worked. Henry was an Associate Member of the IMechE from 1886−1894. He was appointed as Master of the Supreme Court in 1897, but died at the early age of forty-one on 25 August 1897 at Kew.

Later, from 1879 to 1881, three younger brothers, Ernest Woodhouse, Frederick Rainbow and Hubert also attended the school. They very likely took their older brother Vincent’s lead, when they turned to engineering, civil in their case. In 1877, Leeman had been replaced by another ‘Cambridge’ man, John Kennedy. He revised and developed the curriculum quite drastically and provided a curriculum more appropriate for engineering.

1 3 April 1881 Census

2 She stayed with her brother on the night of 1881 Census, but in the 1901 Census she and her sister-in law were living together

3 Pevsner, Nikolaus, 1962, The Buildings of England: North-West and South Norfolk, Penguin Books, p.177

4 White, Francis, 1854, History, Gazetteer and Directory of Norfolk, p.789

5 There were no members of this branch of the Ravens in Great Fransham rectory or indeed in Norfolk at the time of the 1891 Census

6 Raven’s birth year is 1858, not 1859, as he states clearly in the Candidates Circular for Associate in 1898 and later Full Membership of Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) in 1910

7 Evans R.J., The History of Aldenham School 1599-1969, Old Aldenhamian Society, p.102

8 Evans R.J., vide supra, p.119

9 Evans R.J., vide supra from account of his time at Aldenham from 1873-1879 by Richard White, p.121.

10 In Evans, R.J., vide supra, from an account of his time at Aldenham (1862-1867) by D.F. de l’H. Ranking, p.108

11 Evans R.J., vide supra, p.126.

12 The ICE candidate’s circular in September 1910, written by Raven, clearly states that he was at Aldenham from 1872 to 1876, i.e. from age thirteen to eighteen

13 Evans R.J., vide supra, p.119

14 Evans R.J., vide supra, p.121

15 Evans R.J., vide supra, p.94

II

STARTING WITH THE NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY (1875–1882)

By the 1870s, careers, other than the traditional professions of law, the Church, the armed services on land or sea and medicine, were being increasingly developed to include service to the rapidly growing industrial/commercial sectors of Victorian life. Such careers arose partly as a response to commercial pressures from industry, who sought more efficient and cheaper systems of producing goods and partly as a human response to the discovery of an increasing variety of practical applications of science to everyday life. Engineering moved from being mainly an artisan occupation earlier in the century to becoming more and more a middle-class career. This is manifested by the number of clergymen’s sons, like Raven, who, with their talents and moral background, came forward find new careers, for instance, in railway engineering. At the very least, an engineering career provided a steady, if unspectacular, means of earning a living with the added bonus of a comfortable social and domestic lifestyle. Many engineers, financiers and others in trade were, as a consequence, seeking recognition through their professional associations.

There was a connection between the Brewer’s Co. and the Midland Railway, making it more understandable if Raven had gone to Midland Railway (MR) at Derby for his apprenticeship rather than to North Eastern Railway (NER) at Gateshead. ‘Premium’ apprenticeships with qualified engineers had to be paid for, usually by the parents of some benefactor and Gateshead was probably more within Revd Vincent’s financial means rather than having to pay university fees and provide him with upkeep. After all, there would be another five younger boys to see to.

It is possible that Raven’s choice may signify the acting out of some form of teenage rebellion against a path which family and school may have mapped out for him. The imminent Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) Golden Jubilee celebrations of the founding in September 1875 may have been a final spur in making Raven’s decision about career and where he would pursue it. Whatever the truth, his father must at least have acquiesced and agreed to support his decision and pay his fees of about £50 p.a. His successful completion of apprenticeship could well have made it easier for his younger brothers Frederick and Hubert in their turn to take up apprenticeships as civil engineers around the time he qualified as a railway engineer.

His father would have made an approach, including a personal letter of introduction, to Edward Fletcher, locomotive superintendent (LS) to the NER. This resulted in Raven being engaged as a ‘premium’ apprentice with an agreement to pay the requisite fee to the engineer to cover the time the youth spent with him. As he received the premium himself, it was one of the ‘perks’ of the job.

Raven left Aldenham probably at the Easter break of 1875, to serve a ‘pupilage’ from May 1875 to 1880 with the NER Co. The ‘pupilage’ took place at the NER Greenesfield Works on the south bank of the river Tyne in Gateshead. He probably initially worked as a potboy in a kind of ‘work experience’ until his apprenticeship proper started in late 1875 or early 1876. He was fortunate in his choice of master and this could well have helped him to settle as Fletcher’s character was warm and somewhat like his former headmaster, Alfred Leeman.

Arms of the Noth Eastern Railway Co., showing the arms of the three original companies, which amalgamated in 1854.

Edward Fletcher, born in Redewater on 26 April 1807 to Alan and Ann Fletcher, was baptised on 4 May the same year in the Scotch Presbyterian Chapel in Birdhopecraig, Rochester (the Roman Bremenium) in the north of Northumberland, very close to the Scottish border. In 1825, he was apprenticed to George Stephenson and thereafter spent most of his life involved with the railways in the North East. He married a Miss Fedarb and had two daughters and a son by her. He worked for the York Newcastle & Berwick Railway (YN&BR) at their workshops at Greenesfield. The YN&B merged with the York and North Midland & Leeds Northern Railways to become the NER in 1854.

Fletcher lived across the lane in nearby Greenesfield House. His policy as LS was to preside paternalistically over the workshops of the constituent companies of the NER, working on ideas for more efficient and larger goods and passenger locomotives within the limits of the technology available to him. A photograph of him in later life shows a portly man, with a full greying beard looking out with a benign mild fatherly expression. Fletcher was responsible under Henry Tennant for the NER Co.’s GM from 1871–1891. Between them, they gave the company much stability during all the mergers and their after-effects.

Fletcher, although paternalistic and to some extent autocratic, was able to listen to his men, being usually open to new suggestions. For instance, in 1873, the NER engine drivers petitioned him to make the block system of signalling more regular and efficient. He made sure it was done. Despite his new designs being standardised to a great extent during the 1870s, he did not insist rigidly on a company style, corporate image or standardisation of parts, but allowed different locomotive building shops at Gateshead, York and Leeds some leeway with details of design and livery.

Greenesfield Works, Gateshead, in 1864. Little changed until after the Second World War.

Edward Fletcher, Raven’s mentor during his ‘premium’ apprenticeship.

On arriving at Gateshead, Raven must have found the town and the workplace at least somewhat daunting. The depot itself was large and was due to be extended in 1877. The town itself around the river was depressing and industrially urban despite being surrounded by open countryside and villages. He had to learn how to cope with the typical rough and tumble of a Geordie place of work. Coming from the rural gentility of a Norfolk rectory and the comparative refinement of a small exclusive public school in a rural setting, he with his southern speech, his middle-class approach and manners must have been appeared as alien to the his workmates as theirs did to him. The difficulty of understanding the Geordie dialect with its unique accent, archaic diction and obscure vocabulary from both his boss or ‘gaffer’ and his workmates, not to mention their rougher manners, and the sheer number of people in such an industrial urban setting must have presented a challenge initially. He probably lodged somewhere in Gateshead or in Newcastle, as the NER possessed no housing for staff in the area.

From 1876–1878, Raven, as part of his five-year apprenticeship under Fletcher’s supervision, underwent a comprehensive training programme in all aspects of the NER’s engineering work at Greenesfield Works. The site consisted of a massive rectangular building (the original Gateshead Station and Terminus) housing large workshops, which by 1865 had five turntables with eighteen roads for locomotives. To gain practical ‘hands-on’ experience, Raven spent a fifty-three-hour week passing through the company’s various workshops. His reward was 5s a week. He learned what a locomotive was by firing, maintaining and driving it on both day and night shifts. In his second year he received 10s a week plus overtime, followed by 5s increments each year until he qualified. Later, from 1878 to 1880, he went on to work in the drawing office. He would, at this stage of his apprenticeship, learn much about practical engineering, by making technical drawings of items of transport stock, carriages, goods wagons and other apparatus, but most of all about locomotives, especially Fletcher’s class ‘901’ 2-4-0 passenger and his class ‘398’ goods 0-6-0 locomotives, built from 1872 onwards. The latter’s profile has similarities to the contemporary LNWR 0-6-0’s potent influence over much railway design, at home and abroad in the Empire.

This experience would have provided him with much to think upon, learn from and store up for the future. Theoretical work was coupled with the practical knowledge and the skills, which he was able to gain from the ‘track-side’. This meant observing, working and communicating with various grades of workmen, who handed on to him the accumulated fruits of their own experience. Raven, no doubt, was eager to supplement this by studying the underlying theory and practice of mathematics and physics, especially mechanics and electricity.

As will be seen from his later reports and actions, Raven was acutely observant, with a good memory for any details he had seen and for methods he had been impressed by. He learned to gain control of his environment. While seemingly not very imaginative, he not only possessed a powerful intelligence, but an ability to concentrate on matters in hand. These characteristics were a part of a natural endowment, sharpened by a determination to come to terms with any opportunities, which a railway environment of the time could provide for him. This process of learning helped to integrate his approach to his work. It lasted throughout his working life and continued well after his official retirement. He now lodged with a Mr and Mrs Swallow and their young daughter at 81 Wharncliffe Street, Elswick. This was a terraced row of houses running down to the famous Scotswood Road standing above the large railway goods sidings, west of Central Station. He may have lodged there for the whole period from arriving on Tyneside until his marriage.2

Once he left his apprenticeship, likely to have been the end of 1880, he was to gain employment as a junior engineer for one of the best run railway companies in Britain. The company he now worked for, the NER, like all railway companies, had been inaugurated by statute, in the case of NER on 31 July 1854.3 ‘The NER was a well co-ordinated organisation... strong enough financially to provide a really good service, and to be cooperative towards any other railway, which wished to use its tracks.’ The NER became a very great railway.4

901, the 1872 prototype of Fletcher’s 2-4-0 express passenger locomotives. Note the open work splashers.

948, one of Fletcher’s class ‘398’ 0-6-0, built in 1879.

While carrying increasing numbers of both passengers and goods as its lines spread out further into the areas more remote from the Tyne, Wear, Tees, Yorkshire and Humber conurbations, NER gained the majority of revenue from its mineral traffic. This was conveyed from the Pennine hinterlands of County Durham, the Cleveland Hills of North Yorkshire and much of Northumberland to a chain of ports on the East Coast, whose docks increasingly came into NER ownership. In turn, raw materials and other commodities were conveyed there to be processed. The railways became for the nineteenth century what the internal combustion engine would become for the twentieth. This provided a powerful spin off in its stimulation of the consumer market on a much wider scale, not only encouraging travel and holiday taking, but also increasing pressure to bring and distribute goods more and more quickly from sites of production of food or artefacts to a public eager to have them. It also gave a better means of national and international communication, especially through the carriage of the Royal Mail by rail.

By the time that Raven had started with the NER, it had gained a virtual monopoly over passenger, goods and mineral traffic in a region, roughly co-terminus with the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria. It had about 1,500 miles of track, a mainline from Leeds to Berwick, via York, Darlington and Newcastle, with other important loops like Northallerton to Newcastle, via Hartlepool and Sunderland or branch lines sometimes as long as sixty miles, like that from Darlington to Tebay, sometimes a few miles long that to Masham.

Throughout its existence as a company, NER continued to work to secure the boundaries of its compact territory by preventing serious incursions and hence loss of control of its passenger and freight sand mineral traffic movements. The main rivals between Humber and Tweed were absorbed slowly but surely by the beginning of the twentieth century (save the redoubtable Hull and Barnsley Railway along its southern flank, which from 1914 worked jointly with NER and was absorbed by it prior to 1923 grouping in 1922). After the initial amalgamations of 1854, it steadily absorbed other local railways: SDR and its locomotive workshops at Darlington in 1861, the Newcastle & Carlisle in 1862 and the Blyth & Tyne in 1864. It repelled those seeking to make inroads into its territory; especially the powerful LNWR from the west of the Pennines with its proposed North of England Union project aimed at joining up with the West Hartlepool Harbour & Railway Co., by its proposal to build a Wensleydale line to join the MR Carlisle & Settle line branch by Hawes or a proposed Newcastle & Derwent Valley Railway scheme to enable LNWR gain freight carrying access to Newcastle.

To the south, NER relations with GNR were generally harmonious and workmanlike, but to the north, relations with NBR were more ambivalent. NER had to construct its Alnmouth to Coldstream branch to block NBR scheming to find an alternative route from Edinburgh to Newcastle In reality, the NBR in the longer term, lost out to the NER, which out-manoeuvred it. In return for granting NBR running powers from Hexham to Newcastle, NER gained the power to haul the infinitely more prestigious East Coast expresses from Berwick into Edinburgh Waverley. This concession in fact made GNR and NER the main operators from London to Edinburgh in the Rail Races to the North in 1888 and 1895.

The NER’s main operational drawback was that it had no rail access of its own to London, but it made up for this because it was able to charge the lowest railway passenger fares and yet consistently yield the highest dividends, when compared with other British railway companies.5 This payment of good dividends to shareholders over the years remained even after investment had fallen off after the turn of the century and the company experienced an annual deficit.

The directors, being local men, ensured that ports, steel works and especially coal mines had feeder lines from their own businesses to the NER, often with rail systems of their own, led to NER metals. Kirby6 estimated that County Durham alone had a minimum of 5,000 miles of track, as well as direct access to their own port facilities in some cases. The Londonderry Railway was a good example of this independence, although it was eventually absorbed by NER in 1900.

Like all contemporary British railway companies, NER had three distinct sections, namely the Board of directors, its executive officers and its workforce. Each section existed in a clear hierarchical order.

The NER Board consisted of seventeen directors, from whom was drawn a chairman and secretary.7 Ultimately, the Board was answerable to the shareholders, who expected a good dividend in return for their investments. The NER seldom disappointed them. Directors, such as David Dale, James Kitson and Lothian Bell, to give characteristic examples, were appointed to the Board not only to promote the interests of NER, but their own as well, closely involved as they were with the running of different industrial interests, particularly from coal mining, steel-making concerns and the docks on the coast, all of which could benefit from local and regional railway development.

Furthermore, as part of the S&DR legacy, many NER directors and senior officers were Quakers, a Christian denomination noted for its humanitarian philosophy and long history of tolerance of others. They included members of the Pease family, Lothian Bell and David Dale on the Board of directors; Henry Tennant as the general manager (GM); from 1883, the two Worsdell brothers and later their nephew, Arthur Collinson in the LS’s office and their sons also moved into middle management; in the engineering department, there were the Cudworth’s. Later, Ralph Wedgwood came from the famous pottery family to join the GM’s office. Their tolerant attitudes and business acumen enabled the NER as a company to have a view of its workforce as human beings.

This attitude was revealed when, as a means of self-protection tinctured with a measure of common self-interest, the individual railway companies formed themselves into a group during 1868-1870 called the Railway Companies Association (RCA). Their aim was to defend their collective interests, gain trade concessions with other companies and in some respects standardise practice, in such matters for instance as braking or in conduct industrial relations. The NER differed at times from other members of the RCA, especially about ways of dealing positively with its workforce as it favoured arbitration. This willingness to arbitrate undoubtedly arose from the Quaker influence on the Board. Tolerance, combined with a beneficent rationalism, made the NER eager to promote good relations with the workforce, a stance not always recognised for what it was by more militant Trade Union members. Yet, NER was decidedly ahead of its time since most contemporary railway companies refused to acknowledge the rights of railway workers and their Unions. The industrial disputes at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries which afflicted the railways caused much trouble to the NER and constituted a not altogether fair reward for their attempts to work with the men and their Unions.

The senior officers of the Executive comprised various experts in engineering, financial, organisational and administrative fields. They were responsible under the Board of directors for the smooth running of their department’s business from day to day and year to year within the company. The Board, in return, closely regulated their activity. All departments were closely tiered and run in a strict hierarchical order, but the ambitious person with ability, who knew in what direction his future lay, could use the structure to his advantage and gain promotion. Indeed, the officers themselves sought to become increasingly professionalised. This showed in their desire for more training, increased use of graduates and by the need to join professional bodies. For instance, engineers had access to the different levels of membership of one or more three key Institutions of Civil (1836), Mechanical (1847), and Electrical (1871) Engineering. Over the years Raven came to join all three. These professional institutions gave support to a member’s personal development professionally, without being political in the way that RCA and the ASRS would be. In many sectors of the NER, through appointments of able men of experience in management and engineering from other companies, a wealth of knowledge and practical skills were gained. In turn, movements to other companies exerted an influence over their development too. Often there was rivalry between them, but there was also a degree of co-operation especially in the locomotive, carriage and wagon building fields.