Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

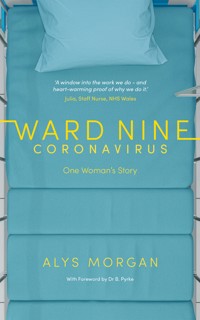

Two of the patients in my room were put onto trolleys and taken out, and then two more women wheeled in. 'This is now a Coronavirus ward,' said Susan. Alys Morgan was admitted to hospital on the 19th of April 2020, with an unexplained sickness which had left her too weak to move. The next day she was diagnosed with Covid-19, but her symptoms were unfamiliar to NHS staff already battling a new and unfamiliar viral killer. This is one woman's account of a pandemic no-one was prepared for, told from the bed of an overcrowded North Wales hospital. It's a story of isolation and survival, mothers and daughters, love and loss. It's a warning to us all; an urge to learn, understand and come together against a 'faceless enemy' which is here to stay. This journal is testament to everything we owe those providing care – and comfort – on the new front line.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 119

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Praise

About Alys Morgan

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

One Woman’s Story

Introduction

Part One

Part Two

Afterword

Further Reading

Conwy Mind

Copyright

‘When we read Alys’ account of the experience of having Covid-19, and also her treatment in hospital, we were in no doubt that we wanted to include it on our Tales of Lockdown blog. Alys’ lucid prose gives the reader a real sense of the disease – and has you hanging on the edge of your seat, willing her to pull through! I would strongly recommend it to anyone if they are in any doubt as to the huge impact of the virus on physical and mental health.’

Polly Wright, Artistic Director of The Hearth Centre

‘This is an honest and emotional account of the realities of having Covid-19. It illustrates clearly not only the physical impact but the trauma and emotional impact too. This is hugely relatable if you have been through this, and a moving insight if you haven’t. It shows how the committed care of others, personal strength and hope make recovery possible.’

Claire, Counsellor, Mind Conwy

Alys Morgan grew up in the West Midlands, and like many people from that area, has English, Welsh and Irish ancestry. She is a retired teacher and librarian who lives in north Wales, and enjoys reading, writing and walking. A survivor of Covid-19, she considers she owes everything to NHS Wales and Mind, who cured her body and soul. This book is a love letter to both of them.

Dr Pyrke lives in Cardiff and has worked in hospitals across south Wales. He is currently an Internal Medicine Trainee working in the second wave of the pandemic.

Ten percent of the cost of this book will be donated to Conwy Mind in helping them to support those, like Alys, who continue to be affected by the pandemic.

WARDNINE:

CORONAVIRUS

One Woman’s Story

Alys Morgan

Dedicated to NHS Wales, who cured my body, and Conwy Mind, who cured my soul.

In memory, also, of all those who have died at the hands of this virus, without their loved-ones by their sides. They will not be forgotten.

A dreadful plague in London wasIn the year sixty-five,

Which swept an hundred thousand souls

Away; yet I alive!

Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year(1722)

Foreword

In late December 2019 a cluster of atypical pneumonia cases of unknown cause were formally reported in Wuhan, China. The location common to this cluster was a ‘wet’ seafood market in the same city. Fast-forward a month and on the 30th January 2020, the World Health Organisation labelled this novel strain of Coronavirus, now christened COVID-19, a cause for international concern.

The news of this new concern permeated the hospital wards in half-understood news articles. Every conversation became a series of unanswered questions: How deadly? How infectious? How would we keep patients safe? We were busy to breaking point already –how could more be done? The stories and images from China, Italy and Spain brought new worries. The major fear unspoken, but widely understood, was that we as doctors may have to become unfeeling triaging machines, dealing out ventilators to a select few. The thought was terrifying.

Then, as time passed, the hospital changed. People came together; plans were put in place and whole systems of working restructured. The National Health Service is a cumbersome juggernaut but once it changes direction and puts its mind to something, it does it well. Intensive care bed capacity doubled; staff were trained to do completely new tasks and whenever their help was needed, willing volunteers from every department – from cleaners to nurses, catering staff to doctors – flooded forward.

Treating someone with COVID-19 is scary. Doctors and nurses are accustomed to feeling in charge, but with COVID-19 there is very little control. In the early days there was no meaningful treatment. We could give supportive care: an intravenous drip, anti-sickness medications, painkillers, oxygen and, at a last resort, being put to sleep and mechanically ventilated. All these things buy time but none of them actively treat the virus. The patient must get better on their own.

To see a patient on oxygen struggling to breathe, and to know how little you can offer, feels like failure. These aren’t numbers in a political briefing. It’s you and a patient in an alien room – and they are unwell, terrified and alone. We should never forget that this is about people. We shouldn’t forget that it’s about our NHS.

On 11th March 2020, COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic – and everything was going to change.

Dr B. Pyrke, Junior Doctor, NHS Wales

One Woman’s Story

I was drifting slowly down a tunnel. It was more grey than black, and there were sparkling lights floating in it. I could hear the voices of Mom and Dad calling to me, and I was quite happy. I went on towards the lights.

There’s truth in those stories we hear about what it’s like to brush close with death. There was light as well as dark. And there wasn’t any fear.

I came back to consciousness with a start. There was a light, but it was the glaring overhead light of Ward Nine. I was in my hospital bed, and being held up and forward. Somebody – a man in full PPE – was kneeling behind me on the bed. There were sharp blows on my back, and his fists were closed in front of me, in what I recognised as the Heimlich manoeuvre. I knew this from First Aid courses at work, but I’d never expected to see it in action.

I was choking, and then it all came up, into the basin that Nurse Susan was holding in front of me.

Later, when the nurses had changed my gown and all the bedsheets, Susan came over.

‘You stopped breathing,’ she said. ‘We called for the doctor, and when he came, he said you were choking on your own vomit in your sleep.’

I’d spent the last part of two weeks being constantly sick; now, apparently, it had nearly killed me.

Susan came closer.

‘You need totry,’ she said gently. ‘You need totry so you can get better. Pleasetry for me. And all of us.’

I closed my eyes.

‘Sue,’ I said at last, ‘I honestly don’t care anymore. If I could close my eyes and just drift away, I would. I think I actually want to die. I can’t stand it any longer.’

I opened my eyes. She was staring at me, and I think there were tears in her eyes.

Part One

It was about the beginning of September, 1664, that I, among the rest of my neighbours, heard in ordinary discourse that the plague was returned again in Holland … We had no such thing as printed newspapers in those days to spread rumours and reports of things, and to improve them by the invention of men, as I have lived to see practised since … But it seems that the Government had a true account of it, and several councils were held about ways to prevent its coming over; but all was kept very private. (Daniel Defoe,A Journal of the Plague Year)

Saturday March 21st

And so they always say that you remember where you were when you first heard of it.

Mom used to say:

‘I was playing in the back yard when war was declared. Dad came out, and sat me on his knee and told me about it. I thought nothing of it.’

Went to the library today and was just browsing when Jane, one of the library staff, came over.

‘Borrow as many books as you want,’ she said, looking distressed. ‘We’ve just had a call. We close at noon today and we don’t know when we will open again.’

I watched as she went round telling everybody – she didn’t make an announcement. I think it was to stop people from panicking.

I gathered up a stack of paperbacks from new books and returned books, and as I checked them out, Tash, the other library assistant, told me about the digital book download service. Not sure I can master that.

I’ve never known public libraries to close before. I was working in Birmingham libraries when the city centre was bombed back in 1974. The next day we all went back in as normal, and every library opened. I remember the caretakers were standing in front of a table as we went in, and they said, ‘Check your bags, please.’ It was the first time I had ever heard that phrase, which I was to hear for the next twenty years.

Mom started work during the war, in munitions, and she went in every day. When the sirens went off, she said, they used just to put on their tin hats and carry on working. In the evening she went to the pictures, usually the Lozells Picture Theatre. One night she decided to go to the Youth Club at Burlington Hall instead. That night, the picture theatre took a direct hit and everyone was killed.

Surely never city, at least of this bulk and magnitude, was taken in a condition so perfectly unprepared for such a dreadful visitation … They were, indeed, as if they had had no warning, no expectation, no apprehensions, and consequently the least provision imaginable was made for it in a public way.(Defoe)

Sunday March 22nd

Johnson was on TV but I didn’t watch it. Can’t stand the way his hair always needs brushing. My dad worked in a factory for fifty years and never turned up looking like that. Brylcreem, and when he couldn’t afford it water, but always immaculately brushed. Followed it on the BBC Live blog. Apparently we are now in lockdown, though nobody quite knows what that means and as far as I know I’m in work tomorrow. A furlough scheme has been announced for those who cannot work, and some of those would not otherwise have been paid.

So what is lockdown? I thought of Mom talking about drawing the curtains for a blackout for the very first time. And curfews. I had a look on the BBC website to see what exactly wecan do. We can take one form of exercise a day, so I will walk down to the beach (the spring weather is beautiful). We can shop for basic and essential goods (no more trips to M&S for party clothes). Travel is permitted for essential work. Our local cinemas and theatres have already closed, and now pubs and restaurants must close their doors too. As must caravan and camping sites, and B&Bs, hostels and hotels. This is a terrible blow to our local tourist industry. Looking at theDaily Post website, I saw that many of our banks and post offices are reducing their hours. There was also a list of which essential services can remain open, including garages, petrol stations – and bicycle shops (so we can all exercise, and cycle to work!).

People are saying that these are the most significant set of restrictions to be imposed on this country since World War II (and already reports of people breaching them).

Let any one who is acquainted with what multitudes of people get their daily bread in this city by their labour, whether artificers or mere workmen—I say, let any man consider what must be the miserable condition of this town if, on a sudden, they should be all turned out of employment, that labour should cease, and wages for work be no more. (Defoe)

I looked up pictures of the Coronavirus on the internet. It is a round ball, with spikes sticking out of it, and looks rather like a sputnik. I stared at it some time. I don’t fancy that rolling about in my body. It is of course the kind of thing that happens to other people.

Monday March 23rd

First day back in work in the new lockdown. Very quiet in the college library. First thing I noticed when I came in today was a hand-wash dispenser presumably put up over the weekend, and Mary the receptionist had put a line of supplies in front of her desk. She gave me some gloves and a hand wash.

Lots of rumours sweeping the site; we’re part of a much bigger college complex. I heard that we might close on Tuesday.

Lots of frantic last-minute arrangements about contacting staff and students via Google Meet. The library at the main site had set up last-minute training sessions on this. Decided to close the library early and go to one at 4pm.

I caught the bus as I’m trying to avoid driving, because of my arthritis, although it suddenly struck me that I was safer driving – travelling in my own car. At Colwyn Bay a poor old man got on, carrying a box and a carrier bag. He didn’t seem well at all. I heard him chatting to the bus driver as he fiddled for change.

‘Got thrown out at two hours’ notice,’ he said. ‘I’m on my way to Llandudno to find a shop door to sleep in.’

I remembered hearing that homeless people living in branches of a national hotel chain had been thrown out as the hotels closed down.

I got out my purse, and gave him some money.

‘Go to the police,’ I said, though I didn’t hold out much hope of anybody being able to help him.

Beggars.

‘Forasmuch as nothing is more complained of than the multitude of rogues and wandering beggars that swarm in every place about the city … It is therefore now ordered, that such constables, and others whom this matter may any way concern, take special care that no wandering beggars be suffered in the streets of this city in any fashion or manner whatsoever, upon the penalty provided by the law, to be duly and severely executed upon them’. (Defoe)

Arrived at 3.30pm to find the library staff assembled. Philip, the librarian, had called an impromptu staff meeting.

‘We’re all closing at five o’ clock today,’ he said. ‘You will all be working from home. You can take a laptop home if you need it, and I’ll be setting up staff meetings on Google Meet.’