5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

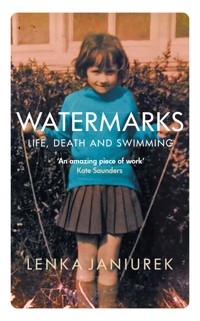

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

An unflinching account of family fragmentation, heart-rending relationships with sons, lovers and partners, and the solace of swimming. Lenka Janiurek's story really begins after the death of her mother when she was a small child, and speaks of the men who came to define her life; she is the daughter of a Polish immigrant father, the sister of five brothers, the wife of one husband, the lover of several men, and the mother of two more. Her memoir speaks of identity and trying to find your place in a country that isn't your own, within a family that doesn't feel like your own. This remarkable book traces Lenka's journey from the UK to Eastern Europe, from the 1960s to the present day. However, across the years, she remains haunted by the rage, addiction and despair of the men she is closest to. Alongside these challenges, she develops a powerful connection with the natural world, particularly water, which provides her with strength and joy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 478

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

3

WATERMARKS

Life, Death and Swimming

Lenka Janiurek

5

Thanks to the Ancestors, my children and the Earth

Some names have been changed

CONTENTS

SUBMERGED

I am in water, submerged and suspended. It feels too tight. There are murmurs, doors bang, there’s the thump thump of going up and down the stairs. Clattering, of cutlery on plates, the coal scuttle, a poker. Voices in different registers, and sometimes silence. An owl, right outside in the dark air. On the radiogram, Tchaikovsky. I kick in a desultory way, my heart’s not in it. The womb gets fuller and tighter still, I am outgrowing the jar and I can’t stop. Even I realise that. And I’m not at all sure what happens next. There’s this serpentine connection to my host, cumbersome, lolloping around my limbs, my face, floating round my neck. There’s the noise of an organ, muffled. There’s a pulse of sustenance, of care, and in the background there’s unease and fear. And then the camel scrabble of kneeling, a lot of gabbling and frankincense, and bells ring. My mother is in her own envelope of faith, and hope.

When it happens I’m waterless. The jar empties, and I’m 14slithery, viscous, amniotic. I’m hurtled, crushed and squeezed beyond bearing. All I can hear is,

‘Bear down, bear down. That’s it. Just breathe. That’s good. Pant. Pant. Now breathe. And … push.’

Voices with a hint of panic in them, under a surface of sensibleness and a whiff of the nobility of suffering. There are the noises of pain. God is mentioned. The bed is ready to receive the fifth child. Two girls, two boys already, they wonder which I am. They pray, they are always praying.

‘In the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Ghost, Amen.’ They pray, ‘Hail Mary, full of grace.’

I slip out to my mother bellowing. I taste blood. There is air all of a sudden, a gasping shock like crawling out of the primeval swamp, with fins and gills and webbed feet. Air is too much for me, then it’s not. The lightbulb light cuts into me like ice. I have emerged, and it’s all shocking and strange. The taps run on full in the bathroom. They cut us apart. I’m slippery. They dry me, I’m a girl. They wrap me up. Too tight, but it loosens. They bathe my mother’s face with a flannel. There’s a glass of water on the bedside table reflecting the light. There are tears in my mother’s eyes. She stares and stares into my face.

‘Hello, you. Hello, little one.’

A tall shape, like a shadow, of my father stands by the window. It rains, splattering the windowpanes. It’s dark outside.

In the future I will give birth to children myself. In pregnancy I will swim, letting the water bear the increasing weight and form. Proud of my shape as I pull myself up out of the pool, seal slick. Training in breathwork, preparing for the marathon of birth. Up and down the pool I will swim, counting, growing, my child’s body adrift in me. In transition, that worrying limbo between the cervix being fully open and being allowed to push, 15I will want to cross my legs and go home, want them all to go away. I will throw a bloody pad across the room, and the nurse in short white wellies will look shocked. In my mind my baby might turn out to be a fish or a monkey, and then everyone will know I am not human after all.

My first day. Daylight is a cloak of mist. And milk, yellowy, watery, sweet. Mine. My father brings a breakfast tray. I meet my older siblings, they meet me. Each fingernail is so very small, I clutch without understanding. When my navy sister sees the black sticky mess in the nappy she will be disgusted although she must be used to nappies and baby shit. I wet myself happily, it’s warm. My mother is trying to balance her Graham Greene novel as she feeds me. People come and look at me. My grandmother, wearing a special shirt with little birds on it, says babies like patterns. And there is talk about baptism. For Catholics the unbaptised child is not good enough for heaven. So I am new and perfect, but not.

Soon enough my mother is weary, clumping down the stairs, are the boys wearing clean shorts, and the girls’ dresses ironed? All the shoes are polished in a line by my father in shirtsleeves in the back kitchen. We don’t have a car, so we walk to church. It’s chilly, echoey, stone-cold. It smells of polish, candle wax, ashes, and earth. I have godparents now. I bleat because the water splashed on my head is stone-cold, and they all pray over me. I am not struck by a thunderbolt of God’s love or light, although Mary was possibly in the corner of the bedroom when I was born. There is only a chipped plaster statue of her in a niche in the church. Her hands stuck in that double blessing pose, she wears a tawdry necklace. The heavens open on the way home, it’s winter. I am a January Sales baby. My birthday is too close to Christmas and New Year, all everyone longs for is an ordinary normal day with nothing to celebrate. A day that isn’t 16special, with no pressure. My baptism is an anticlimax. The water a dribble. Even the cake is dry.

My eldest son won’t be baptised. When he is ten days old we’ll go swimming, and standing in the pool I will let him go, release him from my hands into the warm chlorine-sharp water. And he will sink down and then float up, and swim, waddling like a soft creature taking steps on another planet. He’ll be the best swimmer, Tom, a high diver.

SEASIDE

Now I have a younger brother, so there’s six of us children. Quickly we become ‘the Little Ones’. My father manages a bookshop, the owner has a flat in Filey on the Yorkshire coast, and so we get to go to the seaside in August. For two whole weeks, my father comes for one. The four youngest go in a taxi to the station with the navy trunk. You can pull out the top drawer and it has all our swimming costumes in it. The older ones walk to the station, and we meet up and sit on the long bench with green Twiglet iron struts and wait for the train. There’s our trunk, there are bags, there are lots of bags, and coats. There are steam trains. The whole platform fills up with steam hissing. There are whistles and stoking and clanking and the engine is beautifully grotesque. We sit in a compartment holding sandwiches in brown paper bags. The countryside hurtles by backwards, I can’t quite believe we are the ones moving. We have to change trains at Seamer. The navy trunk is like a butler accompanying us, stoic and loyal. Finally we are 18in Filey, craning to see if we can see the sea. There’s another taxi, craning from the back of that too, I see a glimpse, a strip of it, but ‘hurry up now’, we’re at the flat. It’s upstairs and all lino. We tramp around the rooms. I’m squeaking with excitement, my sister says stop squeaking. Oh, I can’t wait to get to the sea.

At the bottom of the road are the Crescent Gardens. We can see the sea, and it never ends. The gardens are overlooked by vanilla ice-cream terraces, we skirt round flower beds along the warm path then follow the steps down. Down, round this corner, round the bend, down, and down some more. There are 104 steps, I think. And then we come out across the road from the promenade with the railings, and there’s the boating pool. And Filey Bay spread out before us glistening and wet. The sand licked by the tide. There’s Flamborough Head at one side, and the Brigg at the other. The beach held in their claws. There’s the horizon, and the frills of tiny edge waves on the flat sea. It’s calm, it’s sunny, it’s sandy, salty, fishy, it’s all there. And I want to run.

We walk along trailing our bundles, the blankets, the towels, drinks, more sandwiches, buckets and spades, the cricket bat, the wickets, the bails, the balls. I want to drop everything and just run. Down the cobblestones into the tunnel and out onto the beach, we turn right and find our spot and unpack. I changed into my blue swimsuit with the fish on the hip at the flat, slipping on the lino with excitement. So I can peel off my shorts and jumper, throw them down in our new mini home at the beach. Mum has a book and the bags and they are parked along the grey whale curve of the wall so she can lean back and watch and sunbathe and snooze. And I run, the tide’s half out and has left those crumpled ridges like mini desert dunes that are hell to walk on, but I’m running. There’s a spell in my head, I’m spellbound. The first touch, toes sinking, cool waves, rivulets, and white and clear and that sound 19of being washed by it all, the air the sun the sand the salt the water. It’s holy. My older brothers are wrestling, splashing and shouting at each other, I don’t care, their noise sails out on the air. One sister is wading, the other is back at the promenade wall with my mother, arranging her hair. My little brother hums as we stand in it, beside each other, and are embraced. This is the holiday, now. We are in the sea, it’s in us.

In Filey we join the library temporarily each year. Books have to be had, my mother has to have books. Of course we go to church and the Filey priest listens to all our confessions. At low tide we walk to the Brigg with Tata, my Polish father. Following the seaweed-strewn undulating concrete path, up and down, across mussel beds, transfixed by the miniature worlds of rock pools and along to the very end, so we can go round the corner of the headland that’s like an old sleeping reptile. There is a wooden cabin painted grass-green where someone sits and sells purple-wrapped Cadbury’s chocolate. We get this as a reward for all the walking. Sitting on the other side on the rocks Tata shares it out, counting, snapping the squares apart. I wee behind a rock, my brothers point and laugh, I grimace, and they point and laugh some more.

We climb along and there’s the Emperor’s Pool, a stone shelf askew, of emerald water named for Constantine. I want to bathe there, to bask. To be a creature of the deep, an empress with handmaidens. Tata says it’s much too slippery. We troop back to Filey along the clifftop. Climbing the iron ladder, rusty, treacherous, wobbly, vertigo-inducing. The path up the cliff is a long nose, with rabbit holes and gravelly muddy grass, it requires surefooted balance. I don’t have it, my feet hurt. They’ve been hurting a while. The others laugh, imitate my whines, my pleas to be carried or to stop and rest. There’s no more chocolate. 20

This curve of the bay is made of the profiles of stern elders with aquiline features, clay faces that watch forever. We pass the yacht club yachts’ halyards tinkering in the breeze. And it’s possible to get back to the harbour because I’m high sitting on my father’s shoulders now. At Coble Landing there’s ice cream, candy floss, and Corrigan’s, the amusement arcade with pyramids of pennies, miniature cranes tantalisingly about to snare a prize, but never quite. Metal horse races, flashing lights and bleeps, whirrs and the smell of cigarettes. There’s the lifeboat, you can climb a ladder to look at it properly, painted navy and white with a swooping belly. The fishermen wear waders and the tractor rescues the boats as they come in on the tide with great chains, and my father sits with us on the sea wall and stares. While my older brothers whack each other with a tennis ball. They are never tired.

My mother has stayed behind on the beach, just sitting, knitting, reading, snoozing even, she’s on holiday, she takes it seriously. My father is watered down by all the space and the air, even when he shouts or chases my sister with a cricket stump. I never mind so much about him in Filey. At the bakery here there are floury baps, my mother makes prawn cocktail sauce and crams fresh prawns inside. This is my quintessential mother, leaning back into the curve of the promenade wall, chewing a bap with a bit of lettuce hanging out the side, tea from the tartan-patterned thermos beside her, a library book, a rug, sandals off, and sandy toes. Staring out occasionally at the sea and the sky, watching her children from a blessed distance. She very rarely goes all the way in, to swim. Mostly she stands in the shallows, water lapping her ankles, towels and jumpers slung around her like ropes. I wish I had known her when she was girlish, less responsible, less tired or likely to be cross. I wish I had known her without being interrupted. I have to go all the way in, I have to try to swim. 21

Sand in the beds amongst all the sheets and blankets, sand between your toes, sand in your clothes, your hair, sand on the lino. Scratchy, gritty, irritating, sand in your shoes. I keep two small heaps in my shoes on purpose, to take back to York, for after the holiday. Real beach sand. Not the stuff delivered in heaps and wheelbarrowed to the sandpit in the garden. In the future, on a wide Welsh beach I will become a grain of sand in a giant egg timer inside a huge round mandala drawn out with garden rakes. Someone with a drone will film the sand, us people, falling through, marking the time that will be running out.

On the last night in Filey we trail along to the Vinery, a cafe in a greenhouse, and eat Knickerbocker Glories. Real grapes hang from the roof, there is salt in our hair and on our skins. We are dreading going home, licking the tall glasses and our spoons clean.

STORM

Round and round the garden we run and eventually my father picks up the hose and makes a great arch of spray we have to run through. Fleeting rainbow colours, and fear that he might suddenly deftly lower the hosepipe and splatter you full on, controlling the flow with his thumb. We shriek, the grass is getting waterlogged, and slippier and slippier. Then with a great show of huffing and puffing he inflates the paddling pool. Square, canvas bottle-green, slidey inside and repaired in places with the puncture repair kit on the outside. He chases us, he threatens us, he gives us chores in the garden. Weeding, picking up grass clippings from the edges of the rose beds, picking up sticks. We groan and moan, unsure of our ground, of each other, but mostly of him.

In the garden my father is more crazy. Especially with the lawnmower, which lives in the pigeon house and smells of oil and petrol and rags. He has hurled it around before now when it won’t work. He swears, he shouts, he rants, we can’t go anywhere 23near him, we can’t do anything right. He seems to swear in several languages. He goes very quiet and contemplative by the bonfire. And standing beside him, he seems unfathomable when he burns stuff in the brick square he calls the ‘incinerator’. He is always foreign in England, his name, his accent, his gestures, his tastes, his bark, his smell. His memories are foreign, although I don’t realise this, not yet. This is him. And I am me. All I know is he is different from other fathers, but I don’t know why.

Sitting at the dining-room table when his mood is palpably filthy, we are all strung on the edge of our nerves. Waiting. This is what it is like to live with fear. He holds it in his body, ready to pounce. We try to humour him, it doesn’t always work. All eyes are on him, even when they’re not. It’s like living with a big bear with very bad moods. When he comes home from work I listen with absolute precision to the way he opens and then closes the front doors. Is he in a bad mood and is he raging, or merely sulking, simmering? Can he be coaxed cleverly or is it better not to try? Should this great dark cloud of mood be ignored, or sympathised with? I suppose I pick up on this tension and these questions without noticing, from my mother. My father left his country and his parents when he was a teenager. Letters in Polish on thin paper like the hard loo paper at school come sometimes, but not often.

There was one trip to Poland with my eldest sister and my eldest brother after Tata’s mother died. He couldn’t get permission to go before. They wouldn’t let him behind the iron curtain. He pronounces ‘iron’ with the R hard, even though we tell him not to. I can see grey metal, I can’t see anyone behind it. I was small, but very jealous about Poland. Because my brother didn’t even want to go, and had to be bribed by taking cornflakes and tomato sauce with him. There was a fuss. He wanted frozen peas. This brother hates thunderstorms, and will get an award for helicopter 24pilot brilliance in the future. He never takes his jumper off on a hot day either.

Only when I go to Kraków fifty years later and hold the faded pieces of orange card with the photographs of us all stuck on, photos of the fringed pram on the promenade, my father’s legs lanky, my mother steering her brood wearing a home-made dress, do I feel I’ve met my Polish grandmother. Those photographs she must have looked at again and again, wondering if she would ever meet any of us, her six grandchildren. She never did. I will look up at the windows of the flat with the view of the convent opposite. I will walk along the river beneath the castle that the Nazis under Hans Frank occupied. I will hear the sound of their highly polished boots, and their drunken sadist jokes echoing on the staircases and through the courtyards. From when they ruled that dragon town.

On the window seat we are surrounded by playing cards. I’ve lost again, inevitably. It’s just me and my poker brother, it is always poker or pontoon with him, played with matches. I think he cheats.

My parents met at Oxford, and moved to York before I was born. It was a promotion for Tata, to manager. Catholics need room for all their children. Although a bookseller is never well paid, my father had a job and ten pounds in the bank. It was enough. So we live in this big house, renting out the top floor to foreign students from the university. A Lady Guisborough lived here before us, apparently then everything in the house was white. It certainly isn’t now. There was a vegetable garden beyond the rose garden that was full of cabbages when my parents came to look round the house. We thenceforth called this the Cabbage Garden although it’s all grass now. It is surrounded by brick walls and conifers and is a battleground between the washing line, the need 25to play cricket and football at all hours, the grass and compost heaps, the bonfire and, in the corner, the incinerator.

Defeated at cards, I stand on the window seat and look out at the trees in the Cabbage Garden bending, listening to wind belting down the chimney. The sky turns a magnificent slate grey, backlit with yellow, like the sky’s ill. The trees are going berserk out there. I open the window and the air is warm and full of static, bristling. The sky is about to crack open, and I want to be there. I want to see behind the sky. I race to get on my swimsuit with the fish on the hip, to ridicule from my victorious poker brother. I don’t care. On the stairs I see my eldest, helicopter, brother looking worried. He goes to hide in the linen cupboard. This is the brother who never takes his jumper off in summer and needs frozen peas and cornflakes. I wonder if these traits are all related and logical somehow. I can’t work it out.

And I’m running down the veranda steps. The steps my little brother fell up one lunchtime running in for fried egg and chips, and his face came up bloody like the tomato sauce. He had to have stitches and I felt bad about eating the chips and egg anyway, when he couldn’t in all the ambulance drama. But it seemed such a waste. Anyway, I’m running down the veranda steps thrilled, with a laugh in my throat and the sky’s lit up and cracking and violent drums play overhead and I dance round the garden, and jump into the paddling pool. The air is prickling, the sound is deafening, the light magnificent and terrifying, threatening and cataclysmic, and still the rain holds off. I can feel it taking a deep breath. There’s another pause, I ignore my poker brother shouting at me out of the window. The sky’s about to break and I think I’m ready.

Everything has gone darker, and still darker and the trees are rustling and swooping like crazy. The bigtreeinthecorner that’s hollow inside, the copper beech, the chestnut trees, are as excited 26as I am. Anything could happen. My eldest (navy) sister is upstairs in my parents’ room, knocking on the window and looking cross and bossy and then she gives up, tossing her hair at me.

And I’m sitting back leaning on the walls of the paddling pool, bottle-green, blue with my fish, wet from a foot of paddling-pool water, and waiting to be drenched. And it comes on quickly, the rain, the blessed rain. So I’m dappled, then damp and then my hair is plastered to my head and the pool is being hit by spikes, lances of rain and the grass is flooding and I’m wet through. And alone. And it is the most glorious feeling in the whole world. Me in the paddling pool in a thunderstorm and no one can stop me. And the rain takes over completely and the storm slowly travels off a little way and the thunder is not so deafening, more booming than crackling and I sit there and sit there, the trees still dancing all around, leaves and grass floating in the pool, and it’s a long time before I realise I’m shivering. A long time before I go in and peel the costume off into a wet creature to slop on the floor. Before I wrap myself in my light blue sister’s birthday bathrobe without asking. They all say I’m mad. And for once I don’t mind what they call me, what taunts come my way, what looks they exchange amongst themselves, how much they snigger or hum horrible ditties. Because I have tasted bliss, drenched and soaked to the skin. This, in the paddling pool in a thunderstorm, was my true baptism. Christening my soul and my elemental spirit.

THIRST

We didn’t wash the body. My grandmother looked through Mum’s dresses and chose her best one, cerise with gold borders. I privately preferred the blue one. Granny looked out pink lipstick to match. I never played with my mother’s jewellery box again. Never touched the pearl teardrop pendant. We, the Little Ones, my little brother and I, used to pretend her wardrobe was a bus. We’d wear her shoes and lose them, fall off the bus. Putting on funny voices, taking names like Gladys and Ethel. We didn’t play that game again. Like we didn’t pretend to be window cleaners in the bath.

It was to do with corpuscles, white and red. It was 1968. My mother was doing some marriage guidance training, my mother went to Hull. She caught a nasty cold and was in bed for a week. And that horrible January went on and on.

By the end of February there was a plastic beaker on her bedside table, with a toddler’s spout. She couldn’t drink otherwise. 28She was waiting for the Spring, she’d make it to Spring. I could pick snowdrops and put them in the blue-and-white stripy egg cup. Surely she would smell the lilac, and then the roses, surely I could make her a daisy chain? A scientist would come up with a cure miraculously, we could pray more, we could pray harder and faster and longer and do more penance and say more rosaries and surely Our Lady would intervene in blue and cut a swathe through all this red and white corpuscle nonsense, and sort them out. My mother’s face was going yellow and a bit green. She was always thirsty but she couldn’t drink. And there was a tide mark around her lips. One good thing about being married to a bookseller was all the new books, piled around her bedroom, strewn across the eiderdown. Voracious, she was reading Charles Lamb and Iris Murdoch. Except now there were no books on the bed, no newspaper, no concentrating, no more chatting, no knitting, no listening to the radio. Only looking at the curtains, and out at the sky. And I didn’t want to climb in with her, because of it, the Leukaemia. I had to keep going to school, we all did. I perched on the bed and told her I was going to be a toad in a well, under a spell, but only I could help the third son find the Bird of Paradise. I would lie behind stage blocks and leap out crying ‘Caramba’. I could stuff tennis balls up the back of a green jumper to be toad-like. My mother closed her eyes to imagine it. And I closed mine realising that I would have to ask Tata to come, and he’d be the only dad in the whole audience.

I changed her water, I filled up the cup in the bathroom, then held it up to her lips hoping she wouldn’t dribble. And I told her Spring would come. And I told her it just wasn’t fair.

‘Life isn’t fair.’ And ‘Love never dies,’ she said.

These were the talismans she gave me as she came closer to her bed being her deathbed. 29

She died in the night on the Spring Equinox. We all trooped in, the others kissed her cheek. I couldn’t, I just touched her hand, and it was cold. And the miracle hadn’t happened. The undertakers came and they seemed particularly tall and anonymous like they weren’t people at all. My mother had said her many goodbyes, all the priests all the mothers all the family, all the friends and neighbours. She took her death seriously. Only with her little sister did she express fear, asking her to come with her on the raft. Otherwise it was all Jesus, and Heaven and so on. Praying.

There was a Requiem Mass, there was purple everywhere in church, then it was Easter, but no one thought to give us extra eggs, although we privately thought they might. Spring going into hot Summer days seems to betray us. Can I enjoy lying on a blanket on the grass in the rose garden in the daisies licking a vanilla ice-cream wafer with cheese and onion crisps afterwards? Death is not mentioned at school.

My mother wearing a black mantilla singing the hymns heartily, loudly, while surreptitiously doling out chocolate biscuits to us along the pew. My mother in the kitchen, peeling apples, peeling potatoes, in the back kitchen wrestling with the mangle, in the garden, her Scholl sandals clip clipping along, with the washing to hang up in the Cabbage Garden, telling the boys to keep the football away, my mother with pins in her mouth cutting round a pattern with pinking shears, my mother standing in the roses in a flowery home-made dress, my mother drinking sherry with her Cabbage Club intellectual friends, discussing George Eliot, not wanting their brains to dry up with motherhood. My mother clutching, clawing at the sheet, in bed and yellow and dying, and I couldn’t accept it for a long time. Will I ever really accept it? My mother being buried, all daffodils flimsy and fragile in the rainy cemetery, limp jokes about God 30crying, no Resurrection. Wondering if I shouldn’t have worn my red kilt. Stuffing the black corduroy trousers she’d made me and I’d ripped to the back of a drawer, I didn’t want anyone else to touch them, let alone mend them.

Going with my father to the tap near the grave to fill the aluminium watering can with water for the peonies and lupins from the garden she’d never see. I didn’t realise how her death would change absolutely everything and everyone for good. How the temple of our home, of our family, was torn asunder the day she died. I couldn’t have known quite how her absence would always be there in the background like a cumulonimbus cloud, how the space she left behind could be so lonely, the landscape so bleak. Even when I forgot her face.

THE BECK

It’s the same year, 1968. My mum died four months ago. We’ve driven to Hutton-le-Hole in the car (a Triumph Herald, light blue, 7761DN, my father passed his driving test last year). We’re on the edge of the Yorkshire moors, there’s a rug, grass, sheep and their shiny black pellets, a picnic, my father is flat out snoring on the rug. My feet are in the beck, as streams are called in the North. My brothers are involved in an army game which involves stalking through the bracken, lying down, shouting, and pointing sticks at each other. They are on manoeuvres. My sisters are giggling and fiddling with the glove compartment. I wonder if there is chocolate in there. I don’t care, but they beckon me over.

I’m always a sucker for being included by my sisters. I think of them as the navy one and the light blue one, the very oldest and the second oldest, it is hard for me being the fifth child. Singly I worship them. My navy sister has peacock feathers and velvet curtains in her bedroom which also has a bath in it. Her hair is 32blue-black and bushy, her eyes are shoe-polish dark brown. She sometimes lets me ride on her back on the bedclothes when she doesn’t want to get up in the morning, sometimes she tells me to ‘piss off’. She has her own record player and listens to Bob Dylan and The Incredible String Band, and lets me read John Lennon In His Own Write, with ‘Good Dog Nigel’, which I pronounce ‘niggle’. She has an Aubrey Beardsley poster of Salome that I covet. My light blue sister lets me talk to her when she’s in the bath, her skin is milky. She is like a bigger version of me but not, we are curly-haired and blue-eyed, but she is womanly. I get her clothes handed down. She prefers Paul to John in The Beatles. She is terrified of dogs, more than I am, she screams. We sat on top of the piano when we briefly got a dachshund we called Bilbo Baggins. He never stopped barking, and they smell when you’re frightened. So he had to go to another family.

Unfortunately when my sisters are together they are horrible to me, they work as a double act. I am jealous of them being born in Oxford, they had Polish School outfits with hats and sequinned waistcoats made by Mum. I will discover that when it was just the two of them, before the boys and before we, the little ones, were born, my parents used to give my navy sister presents on my light blue sister’s birthday, or she’d be unbearable.

‘Did you know Tata has a girlfriend?’ my navy sister now says unbelievably.

She is always straight out with things.

‘What? Of course he hasn’t,’ I say.

What can I say, are they teasing me?

‘That’s what you think, but he has.’

‘And we’ve got proof.’

My light blue sister likes saying ‘we’, meaning not me. They giggle and there is a lot of eyebrow raising. They do this a lot these days. 33

‘But … well. No one would want to be his girlfriend. And what about Mummy?’

‘Well, he has. Do you want to see her? Do you know what she’s called?’

‘Don’t tease me. What do you mean, see her?’

It is too much for me to think she might have an actual name.

‘Why on earth do you think we’ve made this up?’

‘He told us. He always tells us everything first.’

‘What?’

‘He told us all about her. Honestly.’

‘I don’t believe you.’

‘Look at this book, then.’

‘What’s that got to do with it? Tata can’t have a girlfriend.’

‘He can. And he has. Look.’

A black-and-white book jacket. Photographs of a straight-haired woman with a lot of teeth. I wish my feet were still in the stream.

‘That’s her. S.’

‘No. It can’t be true.’

The woman is twenty-three, it says on the cover. My father is forty-eight, my father has six children and a dead wife. My father still has black hair, he is lean, tall. I would not say my father is handsome, but other people might.

‘He’s going to tell you all about her. He wants us to meet her.’

‘Don’t be silly. You’ve made this up. All of it.’

‘You’ll see. He hasn’t told the boys yet, but we thought you’d like to know.’

My father is grunting in his sleep next to the bracken. It can’t be possible that he has a girlfriend. In the same way he told us about the Leukaemia in stages, oldest, the girls, first, then the boys then us, the Little Ones, last. I have leapfrogged into knowledge I don’t believe or want or understand. Fathers can’t have girlfriends. There 34is some chocolate in the glove compartment, at the back. My navy sister opens it boldly, snaps it, breaking all the rules. There is a silence. There are sheep, the sounds of warfare in the bracken, a car goes past, a family floats by looking bored out of the windows. I envy them. I envy their boredom, and the fact that they all fit in the car without anyone having to sit in the boot. The fact that there are two parents looking bored. I look at the pictures of S. I don’t want to, but now I have to. Then I go back to the stream, back to building my own private dam. Selecting a stone to take home. Wait for my father to clear his throat and tell us little ones finally about S. Using the same hesitant and embarrassed tone he had when he decided he should sleep in our room after Mummy died, with me and my little brother. And he scared us with his coffin-shaped sleeping bag on the green camp bed, and the earth he’d stowed on top of our wardrobe from Poland. It shouldn’t have been so frightening, but it was. We were glad when he went back to his own room having agreed privately that although he’d said we needed him to sleep in our room, we’d thought he couldn’t face sleeping in his room without her.

My feet are waterlogged and freezing. Tata wakes up and shouts at the boys. We visit a church on the way home, for the first time he doesn’t loudly whisper, ‘Pray for your mother.’

He doesn’t even mention praying. He tells us before bed that a woman, a good woman called S, is coming to stay and meet us next weekend. From London. We might like to go and collect her at the station. We might have steak and ice cream for supper. There is no mention of girlfriends. I pretend not to listen or really care what he says.

My little brother speaks out of the dark, after Tata has turned off the light and we have listened to his footsteps going downstairs, he says, ‘We might be allowed cider.’ 35

‘We never have steak,’ I say.

‘I think it can be a bit rubbery, chewy.’ He sighs. ‘Well, it’s obviously ridiculous. It won’t last.’

My little brother still sucks his thumb, there is a knobble on his knuckle from it. He is seven. My navy sister is sixteen.

POOL

Somehow I still haven’t learnt to swim. We’ve been going to the swimming baths for years, and I’m embarrassed by the calluses on the soles of my feet, and by my father trying to make me, force me to swim. I can’t breathe with water wings, arm bands haven’t been invented yet, I panic. There are too many people and I don’t like the echo. My father clenches his teeth, like when he clutches my feet too hard and slices, it’s all tense, all nerves, always near to shouting. My mother used to calm him down.

S had a custard-yellow going-away suit, the boys were altar boys, we girls the bridesmaids. S’s father is the same age as mine. Really. In the photographs his teeth are braced in a smiling fury. Tata and S went to Formentera on their honeymoon, where her parents have a villa. They ate watermelon, she said on the postcard. Granny looked after us, but I haven’t seen her since. People have stopped talking to my father. We are not allowed to mention my mother, we’ve got S now. She is hard to explain. 37

I’ve been to London now, the furthest I went before was Oxford. Before the wedding we were taken on a whirlwind of sights, the Tower, the planetarium, the waxworks, the boys hated the National Gallery. We went to see The Mousetrap. S’s parents live in St John’s Wood with her old nanny, who makes apple pies with cloves and walks an Afghan hound in Regent’s Park. S’s book made her famous, and her parents aren’t sure about this. We were all photographed ranged on the climbing frame at home, and it was in the Daily Mail. ‘That rag,’ my sisters said, and refused to smile for the camera. They refuse to talk to S. S’s father reads the Financial Times, his father owned mines in South Africa, her mother plays bridge and tennis and is always a Caramac-brown colour, all year round.

The wedding was in Hampstead, and my poker brother got so drunk on the champagne he had to be carried outside and laid flat out on the grass. My navy sister made us kaftan dresses, with flared sleeves – her flared sleeves you could hide things in, mine were tiny, hardly flared at all. I thought the white socks I wore with the black shoes didn’t go with the teal corduroy, but I didn’t say anything. Really, in the last while there has been a lot of posing for photographs. As if life is happening so quickly and we keep trying to hang on to it, but we can’t. I have a new brother now, a half-brother technically, but a person isn’t a half, even if they are a baby.

Anyway, now we’ve come to stay in a manor house in the country, it’s amazing, there’s a boat and a swimming pool and a croquet lawn and chairs on wheels to sit on in the courtyard. We brought our dog, Fuzz, but he’s eaten some ducklings and so we locked him in the dungeon that’s a table-tennis room, but he ate through the door, and so S had to go into Oxford to get some hardboard and paint to repair it and hope no one would notice. It’s an extremely old door with metal studs on it. 38

The pool is surrounded by a yew hedge. Apparently from above it is shaped like a grand piano. The straight line of the keys hold the shallow and the deep end, the curvy bit is all deep end. But you can’t really tell on the ground about the piano, you’d have to be told. There’s a massive slide with water that trickles down it to stop your bum sticking. I sit up there with my legs hanging down onto the slide bit and S is down in the pool treading water, and encouraging me to slide down saying she’ll catch me, ‘It’s fun.’ Her teeth flashing at me. I sit up there for half an hour until she’s gone away. Then I retrieve my legs, turn round and creep back down the ladder like a spider. S’s method with children is half humiliation. It would be better if she left me alone.

I decide to teach myself to swim in my own way. In the shallow end, slowly, in between people coming in and out. I am the safest person I know. S is noisy, she drinks gin, she smokes, she wears jeans, she swears a lot, she laughs, the au pair looks after my new brother. My father is working. I suppose S is solving the problem of holidays for all us children like this, by asking her rich friends to help.

I develop my own swimming style, the one that’s best for me, without anyone shouting or encouraging me. I do it quietly and gradually with just the birds for company. When people come into the pool I cling to the sides, or sit on the edge. I do breaststroke arms and crawl legs, it’s easier. And I build up to actual swimming. Even though S was Olympically trained, like her mother practises at the Wimbledon club and gets the used balls from the Championships (they only use them for seven and then nine games, that’s why they’re always saying ‘new balls’), I don’t follow S’s advice. I swim my own way. My sisters have left home. The navy sister has gone to university, my light blue sister has gone to stay with another family. So I’m the only girl. S isn’t really like women I have known before. 39

I’ve done it at last, I’ve taught myself to swim. And I beat my poker brother at croquet. He hasn’t worked out how to cheat at that, yet. I swim four or five times a day now. You can here. My feet and hands get waterlogged like a crocodile but I don’t mind. And there’s a big log fire in the house with a kind of chainmail curtain as a fireguard. They have a butler here, there’s a bell on the dining-room table. When my father comes for Easter, he says, ‘I just don’t like ringing it. It’s silly.’

His finger hovers over the bell like it’s a slimy sea anemone. S laughs loudly from the other end of the table. My helicopter brother reaches over and rings the bell instead. The butler appears, he has striped trousers.

We eat a whole salmon on Easter Sunday. It has been flown down from Scotland for us. M, the rich man whose house this is (he has a few), caught it on an island there and had it sent here, by plane! My father says we should help with the washing-up, but anyone can see that the butler and the housekeeper don’t want us in the kitchen. It is clearly their kitchen. But we do as we are told, the boys clear the table. There are loads of different sets of plates and platters and cups and saucers on loads of shelves in the kitchen. I don’t like the green set. There’s an Aga, and a whole room full of wine. I fill up one of the sinks to wash the glasses. Of course I break a wine glass, it just slips, then there’s blood in the hot water. So I run out of the kitchen, down the passage past all the storerooms, across the gravel and round to the back of the barn, and then along the path to the boathouse. I am frightened of being told off. There’s a rowing boat just sitting in the boathouse. We are allowed to use that too. I can hear them calling me, well, S calling me. No one finds me. I only go back after spending a long time in the boathouse, where there are all these reflections so it’s almost all in black and white because of the shade. There are 40ducks, I don’t know if they are the parents of the ducklings that got eaten by the dog. I am shivering when I go back, and bracing myself. But everyone has gone off to the tennis court.

I like the river here, it’s the Thames. There are bulrushes and you can just sit on the bank in the grass away from everybody and everything, and listen to the trees. In the future I will have sex here. No one at my new school would understand about S, let alone this fairyland place, so I’ll say nothing about this holiday. However much my brothers mock me, I can swim. I can float on my back like a starfish and look at the sky in the deep end. All the deep dark green water holds me, like I’m weightless. I’ve discovered it’s easier to swim in the deep end because you can’t touch the bottom. I was all wrong about swimming. And because my feet are painful with too much walking, it’s a new piece of freedom. Swimming doesn’t hurt. I know I used to have a panicky comical birdlike hop along the bottom in pools, now I just breathe in and glide.

BATH

I’m washing my hair in the bath. I don’t have baths with my little brother any more. I kind of miss it, we used to play being at sea, or scrubbing the sides and talking in funny voices. I was in charge at the front and rowed the hot water to the back. My little brother would call me bossy. I liked it when we were the ‘Little Ones’, that’s what Mum used to call us. I liked playing pirates with the settee cushions. I liked the little-people-who-lived-in-the-flower-bed stories she told us out of thin air, we and she never knew what was going to happen next. I have my own bedroom now, up in the attic opposite the au pair’s room. I painted it orange and antique gold. Tata did the window in gloss. I have my own washbasin. There is ice on the inside of the window in winter, but I can see the stars better from the attic.

I go to an all girls’ school now, uniform, navy blue. I don’t go to the convent where everyone else from primary school went, so I am the only Catholic. We have been doing the Battle of Thermopylae 42in ancient history. In needlework I’ve made an apron and a shirt with a collar from scratch, buttonholes by hand and everything. I know Mum would be proud. S doesn’t sew and she hates cooking. I just wear my self-made shirt anyway, unfortunately no one in my family is that impressed.

It seems like most of the girls, in fact everyone else, have got their periods. It seems like I’m the last one, still waiting. Sometimes I wonder if I’m not really a full girl, because it hasn’t come. I’m nearly fourteen. And I don’t understand why the biology teacher Miss Smedley got so angry with me. We have this subject called ‘Hygiene’ once a week. We cut out pictures of food and stick them in our books and labelled them. We drew diagrams of rabbits’ reproductive systems. And then the human reproductive system. The week before half term she asked us if we had any questions, and told us to write them down and put them in a question box. It looked like she’d wrapped a Kleenex box up in brown paper to me. Of course we were all hoping she’d start talking about sex, we hoped she’d be embarrassed and then forget to give us homework. But she only asked us for questions, anonymously. To be put in the box by next lesson.

And of course I forgot, so just hastily scribbled something in the notebook I got in my pillowcase at Christmas, then tore it out, folded it up and put it in the box. No doubt some of the swots had thought up complex enquiries. Miss Smedley gave me a particularly fierce stare, she looks like a walrus, although that could be unkind to walruses since I have never actually seen a walrus close up, or at all. My hair was probably coming loose again, she is very big on tying your hair up, and doing up your science overall properly.

Miss Smedley is not overkeen on me, she makes me feel improper. Possibly because I felt-tipped my initials on my 43science overall rather than having elaborate embroidered ones, and possibly because one of the overall ties fell off and I lost it and made another one out of pink velvet. I don’t think she appreciates me.

The next Hygiene lesson arrived in due course, and Miss Smedley made a great show of drawing out slips of paper and answering some of the questions from the box. All dull. And then she paused dramatically and said, ‘Now, I’m very sorry to say one of you has taken it upon themselves to use this opportunity to write something shameful. And not only that, they have tried to make an exhibition of themselves by writing on yellow paper. Their question was quite beyond what is proper.’

She always purses her lips into puckers. People were looking round and rustling with interest. Dear me, I realised she was talking about me. The yellow paper.

‘They will know who they are, and I will not stoop to giving them any satisfaction to ridicule this exercise … by being so very … unhygienic.’

I spluttered, and most likely went bright red in the face. I just can’t stop blushing happening.

Anyway, I’m lying in the bath wondering if I’ll ever have a period. And I never got an answer to what to me was a perfectly innocent question.

‘Can you still wash your hair in the bath when you have a period?’

Anyway, I’ve got a good spring crop of pubic hair, I smell more when I sweat. I can’t say I really have breasts yet but there’s time, maybe at some point I will have a bra and periods, and then I’ll grow up. My sister (light blue) told me all about periods ages ago. After Mummy died and before she went away to live in the caravan. We were eating fish fingers, mashed potato and peas with tomato sauce on the veranda. 44

‘It’s agony. You won’t be able to bear it. And all the blood.’

‘What? How much blood is there?’

‘There’s so much blood, it pours out of you.’

‘But where from?’

‘It’s your eggs bursting, stupid. Do you want to know about sex now, what they do?’

‘Who?’

‘Grown-ups. Tata and S. How do you think babies come? How do you think they get in there?’

I was thankful when the front door slammed and it was the others coming back from a football match. S was in London. My light blue sister left soon after, with two cardboard boxes of clothes. She took her bike too. She was the only one of us with her own bike, a brand-new Moulton, she’d saved up for it for ages with the money her godmother sent every year. My godmother went to live in Tasmania, and my godfather is a missionary in Lesotho. I only have a small fur purse to show for this, with a few shells with pink spines inside it, from a beach on the other side of the world. And presumably there are prayers coming over from Africa when he remembers me, but nothing I could ride.

COFFEE

I get the bus into town and walk over Lendal Bridge, past the Bar Walls and the peacocks in the Museum Gardens. There are two rivers in York, the Ouse and the Foss, the Romans were here in style and called it Eboracum. The city is built on bones and broken pots and mud. The bridges are like relatives, I know them so well, Lendal and Skeldergate are metal with shields, Ouse Bridge is stone. If you walk along the Bar Walls you can see why York floods, the city’s like an upside-down hat. The nearest proper hill is Garrowby Hill, fifteen miles away.

I’m working in the shop. Not the new university bookshop in the library building with the cafeteria and phones with helmets like space men, with the lake with the plastic bottom. I’m working in the shop in town, in Stonegate, the street leading up to the Minster. The building is new books downstairs, secondhand and ‘antiquarian’ up. There are loads of staircases and creaky rooms, the one with no windows was used for cock-fighting ages ago. 46The art books, secondhand, are in the front room on the first floor with the bay window overhanging the street so you can examine all the tourists and they don’t even know you’re there. People used to shake hands across the street through the upstairs windows. Well, I must say, they must have had long hands. Maybe that is in Whip-Ma-Whop-Ma-Gate, or the Shambles near the market, markets are a bit of a shambles, so it’s a good name. That’s where Margaret Clitherow was crushed to death for being a Catholic. My father is the manager so he is in charge, and he makes sure everyone knows it. They freeze when they hear him on the stairs. There’s the children’s shop next door, I want to be in charge of the window and arrange my favourite books in there. My father has unilaterally banned Enid Blyton, you have to say ‘go to Smiths’ to her fans, and then they look crestfallen and puzzled and back out of the shop. In the rear of the children’s shop is the coffee room where all the staff come on breaks and try not to complain about my father. They call him Mr Jan. They call Mrs Shimiratska, Mrs Shimi. The others all have English first names. Mrs Shimi is the only other Polish person I know, except the man who brought the plum trees for the garden and he lives miles away. Mrs Shimi does the accounts with a little machine and takes out her false teeth. Later her office will move up the road and round the corner to Coffee Yard.

I sit in a back room with a lot of dust mote columns and falling-apart cardboard boxes full of duplicates of invoices that need filing in alphabetical order. They’re not very important, but quite important, and I’m getting paid. You file them under the publisher’s name. They are flimsy, almost see-through, and either an insipid lime or lemon colour.