Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Vybarr Cregan-Reid is an unlikely academic. Someone who knows what it's like to be written off, who left school with no qualifications, who desperately needed a second chance. He also understands better than anyone the power of literature to change a life. From a turbulent start, through a disastrous education, truancy and petty crime, to a distinguished career as an English professor, We Are What We Read weaves Vybarr's own unexpected life in books with a spirited history of the war on the humanities, uncovering the profound impact that books have in shaping our reality at a time when their value is under attack from governments around the world. Part memoir, part manifesto, part history, We Are What We Read is not just about how education can place you back on the right side of the tracks. It is also a rallying cry for the importance of literature in a world where the arts are being squeezed out at every level and where book bans in schools and libraries have surged to record highs. It's about the joys and the transformational power of reading and how our brains are rewired by books, exploring how literature offers a vital means of connection in a fractured world. Reading is not merely an escape – it's an essential part of who we are.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 430

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

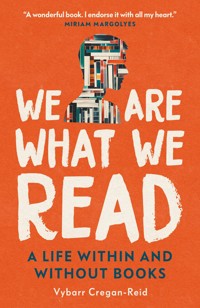

praise for we are what we read

“A wonderful book. I endorse it with all my heart.”

Miriam Margolyes

“The boldest, clearest, most beautifully written articulation I have yet read of the life-changing properties of literature and why we disdain and downgrade its study at our peril. We Are What We Read should be a set text for the next Education Secretary and required reading for anyone who doubts the transformative potential of arts and humanities subjects.”

Caroline Sanderson, associate editor, The Bookseller

“If you are a book lover, this is a must-read. Intensely personal and intellectually robust, this is an exploration of the mighty novel and the power it has to shape lives, both collectively and individually. Necessary, provocative and moving, I read parts out to friends (‘did you know that…’) then found myself both sobbing and laughing out loud, sometimes on the same page. Vybarr is a guardian of the arts who deserves his own statue.”

Catherine Gray, Sunday Times bestselling author

“A deeply moving memoir and an impassioned ode to the beauty of reading and the magical, transformative power of literature. This clarion call for the preservation of the humanities is one we should all heed.”

Jules Montague, consultant neurologist and bestselling author

“This book tells important and arresting truths about books themselves: how they make us as readers, how they help us to learn complicated truths that can’t be found elsewhere and how crucial the study of them is to a life fully lived.”

Professor Gail Marshall, chair of University English and head of the School of Humanities at the University of Reading ii

praise for footnotes: how running makes us human

“A wonderfully subtle and ambitious book.”

The Guardian

“A blazing achievement. It burns with restless energy as Cregan-Reid, alive, alert, wholly and gloriously present, sets out his manifesto.”

Katharine Norbury

“Delightful … An entertaining combination of personal narrative and rich literary episodes.”

Times Literary Supplement

“A book in which the striding energy of the prose matches its subject.”

Iain Sinclair

“Insightful and intoxicating.”

Lynne Truss

praise for primate change: how the world we’ve made is remaking us

Best Books of 2018: Science

Financial Times

“Nature and nurture commingle to fascinating effect in this study of how the environment humans have so thoroughly altered is altering us physiologically.”

Nature

“A work of remarkable scope.”

The Guardian

iii

v

To those everywhere who have taught tertiary arts and humanities in the last decade, drawing on reserves of tenacity, patience and generosity. And to my mum, for all the same reasons.

vi

vii

‘I am no novel reader—I seldom look into novels—Do not imagine that I often read novels—It is really very well for a novel.’ Such is the common cant. ‘And what are you reading, Miss—?’ ‘Oh! It is only a novel!’ replies the young lady; while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame. ‘It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda;’ or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.

Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey

Only three or four things are worth living for; the rest is shit.

Carlos Ruiz Zafón, The Shadow of the Wind

I paid $120,000 for someone to tell me to go read Jane Austen! And then I didn’t.

John Mulaneyviii

Contents

1

This good-fellowship – camaraderie – usually occurring through similarity of pursuits, is unfortunately seldom superadded to love between the sexes, because men and women associate, not in their labours, but in their pleasures merely. Where, however, happy circumstance permits its development, the compounded feeling proves itself to be the only love which is strong as death – that love which many waters cannot quench, nor the floods drown, beside which the passion usually called by the name is evanescent as steam. – Thomas Hardy, Far from the Madding Crowd

1

Books hold most of the secrets of the world, most of the thoughts that men and women have had. And when you are reading a book, you and the author are alone together—just the two of you. A library is a good place to go when you feel unhappy, for there, in a book, you may find encouragement and comfort … Books are good company, in sad times and happy times, for books are people—people who have managed to stay alive by hiding between the covers of a book.

E. B. White’s letter in Letters to the Children of Troy

It took thirty-seven years to finish the novel. Had I been writing it, perhaps that would have been an achievement. Instead, three-quarters of my life had been exhausted awaiting the completion of Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd, finally getting to its closing pages and Hardy’s conclusion that real love, love as ‘strong as death’, is that which is made of companionship and passion.

Across such a span of time, some people have families. They might rise through their careers, retrain and rise again in another, or they might spend their time travelling the world. Entire lives get lived in less than thirty-seven years; full ones, too: Jesus, Mrs Beeton, Bob Marley, Sylvia Plath, Keats, Kurt Cobain, Biggie and Tupac, Robespierre, Bruce Lee, Vincent van Gogh, and most of the Brontës, including the brother. Wars are won and lost, dictatorships rise and fall, empires are dismantled. And what had I done with my 2time? I’d finished a book I’d been set to read at school recounting the conjugal exploits of the spunky Bathsheba Everdene.

While I was well on my way through the book, I knew finishing it was going to be a big moment. It had to be, given how my life had played out since I’d first read those dozen or so chapters when I was fifteen years old. What I didn’t expect was for it to be such a memory rush. The novel joined two disparate moments, which now sparked like live wires, flashing up thoughts and revelations about how far I’d come and how much reading had changed me, what it had done for me and, too, the ridiculous things that had been done to change how it’s taught.

Back then, I was a feckless adolescent, as uninterested in school and study as you might expect. My only interest was music, and I mostly got my music by stealing it. I don’t mean I illegally downloaded it. No, I removed scores of LPs from shops, in bags, behind bags, stuffed up school jumpers or beneath conspicuously outsized coats. Theft was the antidote to the staggering boredom of hanging around shopping centres while skipping school. My side hustle was graffiti, a pathetic attempt to leave some sort of mark on the world, to prove I was in it and I existed.

And with every bad decision, my life got a little smaller. What was the point of going to school? I just failed at things: as ill-suited to scholarship as I was to friendship. What was the point of taking risks? What was the point of trying when I knew things didn’t work out for people like me? Instead, it was easier to huddle into myself, limiting effort only to what worked, until one day I realised I’d become so small that no one even knew I was there any more. Then again, invisibility is a superpower to a thief. 3

i

Since those days, I have developed another superpower and I am more grateful for it than anything: I developed a hunger for stories. And if you’re going to read, if you’re going to spend thousands of pounds across your lifetime on reading glasses and hours of your life cleaning them, if you’re going to learn to enjoy that exquisite pleasure of the gradual transition of a book’s heft from your right hand to your left as you make your way through it… if you are going to read a lot, then Thomas Hardy, despite first impressions, is going to make his way, at some point, back on to that imaginary stage.

At first, Far from the Madding Crowd was tainted by association with school, but much later, I began to suspect the book might be quite good and hoarded it as an unexplored pleasure, deferred to the future.

You see, in those intervening thirty-seven years, I had fallen in love with literature so deeply, so unproblematically and so totally that I wasn’t fit for much else. I had no choice but to become an English literature academic. That younger, indolent version of myself could not have foreseen the embarrassment that stung every time I had to admit, at conferences or in seminar rooms, to not having read the novel. ‘Why embarrassment?’ you might ask. It was because I specialised in, of all things, nineteenth-century literature, and worse, I taught an entire course, by choice, devoted to the work of said Thomas Hardy.

ii

The shiny new title of professor had been bestowed on me a few months before the chaos of the first Covid lockdown. After my fair share of challenges, I was finally living the good life. I’d made it to the summit of my career. That career, and its associated side gigs of publishing books, appearing at literary festivals, being on telly and radio and making radio series for the BBC to be broadcast all over the 4world, had also taken me all around the globe. In recent years, off the back of work, I had visited Japan, Singapore, Boston, Buffalo, Detroit, Seattle, San Francisco, Reykjavik, Sardinia, Groeningen, Brussels, Paris, Cyprus, Kenya, Venice, Rome and Berlin. It had taken decades, but I’d somehow made this work my job. Now, I was a professor too.

You’re supposed to be cool and reserved as a professor. You’re not supposed to like it too much, lest it seems you are unsuited to the station. But how could someone not feel grateful when data collected by the Royal Society in 2010 showed that less than half a per cent of students who complete doctorates go on to become professors?1 Now, I was finally at the point where I wouldn’t have to grind or level up any more. Instead, I could just get on with the work I loved doing and was good at.

What also made it so special was that, as a child, I hadn’t once imagined such a future. No one else had either. One of our neighbours growing up was also, briefly, my maths teacher. When my mum told him the news (she told everyone she met), he was nonplussed: ‘Vybarr? You mean, your son Vybarr… Really, Vybarr?’

I had done well in primary school, but awful, life-changing stuff rained down upon our family and after that I consistently ranked about twenty-sixth in classes of not much larger. What healed all that damage for me in the end was quite simple. Reading.

iii

I was able to exult in my new role of professor for only a matter of weeks before Covid struck. At that point, I became one of the billions whose livelihoods had been steered violently off course by the pandemic. Some were made redundant, some were furloughed, some were clenched in the purgatory of zero-hour contracts, some 5were overworked, many were just sacked. After a few weeks of enjoying my small success, it felt like I had stepped on the ninety-ninth square in a game of snakes and ladders. The pandemic was going to slide me all the way down the back of the serpent to the very beginning of my career. Everything gone. The news arrived that our department was to be cut by 50 per cent. I would likely be out.

It was all of this that drove me back to Hardy, where it had all begun. It was principally because it looked like the window of opportunity for me ever getting to teach Far from the Madding Crowd was closing. I was about to become one of the many casualties in the war on the humanities, which had been raging for decades. So, I set the novel on that year’s Hardy course, not really considering what the impact of reading it might be.

iv

Being an academic with a heavy teaching load means that you don’t so much read books as ram-raid them. You bungee into them, quickly grabbing only what you need before the elastic snaps back and you flee the scene, bound for your next crime against scholarship.

After I’d been rescued by books in my twenties, I read at home, on my way to work, at work, on my lunch break, on my way back home. I became an expert at negotiating people and street furniture as I walked with my head in a book, never once barging shoulders, missing my footing or disappearing down a manhole. I had the energy and hunger that only unsatisfactory work generates, and that work also kindly endowed me with the motivation to change, to study long and hard to get degrees, fellowships and a doctorate. Those changes came from my reading.

Now, in the present, my brain was mush from exhaustion. The 6last two books I’d read for choice were both thrillers – carefully chosen in the hope that they might restore the compulsion to read. The experiment tanked. The first took me four weeks; the second took me six. Over two months of reading and all I had to show for it were two blown-out paperbacks in larger print than was necessary, with chapters a lot shorter than they ought to be and generous blank pages between to bulk out the sections.

v

On the day I started rereading The Hardy Novel, I had hundreds of emails to contend with, research impact statements to draft, references to write, meetings strewn across my calendar like an upturned box of drawing pins. I had lectures to record, tutorials to arrange with trainee doctors in the medical school and a pandemic to dodge. Nonetheless, I had previously worked out exactly how many days I would need to get the novel read in time for the class, and so I had to begin.

I shut my computer down. Heavy with work worries, I reclined into a protesting chair, but when I opened the book, I was suddenly back with my fifteen-year-old self. In a moment, I was in the plush armchair in the front room of our house, my legs curled up under me, sat in a single shaft of sunlight with dust motes drifting through it. I could remember the book’s distinct orange binding, the colour of a Club biscuit, and the malformed geometry of the used paperback. Its dog-eared cover was cracked and torn but with a splodgy painting of some sheep, a gate, a forest and a golden sunset. This was not an enticing cover to a teenager more used to the Mardi Gras palette of Asterix and The Adventures of Tintin. But I’d made myself comfortable and even though it looked like there was a reasonable 7chance the novel might be about sheep, I was determined to read Thomas Hardy.

It had been a titanic effort on my part to commit to sitting still for several hours to do anything, let alone to read. My heart breaks to think of that kid, a kid that had learned to hate school and everything it represented. Yet, in an attempt to please, to do what I knew was good for me, what was right, I tried. I really tried. Nobody saw the effort; nobody valued it because it was just what was expected of me. It didn’t matter that I couldn’t do it.

Why is it that we are never fully present in these moments of great importance in our life? As I sat there, I failed to grasp that my future was in the balance. I didn’t realise it but the portal to another world was open before me, yet I treated it like I was being forced to holiday with grandparents.

I leafed past the prelims. Chapter One. A long description of Gabriel Oak. Then, oh no! It is about sheep.

But I was determined. For hours I sat, eventually making it to page eighty-one. Later on in life, I might boast that I managed to read Margaret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin on the same day as J. M. Coetzee’s Disgrace, but on that day, I read far more than I had at any previous point in my life. The Hardy-esque irony, the tragedy in miniature that was awaiting the completion of my work, was the simple realisation that no one had told me you had to focus and try to follow the rill of the story. When I got up from the chair and realised that I couldn’t recall any of what I’d read, I was a Sisyphus watching the stone roll down the hill but one who just could not be arsed to push it back up.

Why had no one told me that you had to concentrate when you read? I was outraged, properly angry. Then, acknowledging that it was all my own fault, I hit the ground like a safe. The outcome was that I turned my back on literature in a huff of such adolescent 8magnitude that it lasted for years. Looking back, it feels as though the very idea of ‘school’ was in the balance in that reading session.

School lost.

vi

Now, here I was in the present, chair at full tilt, feet on my desk, the living embodiment of the fact that my literary career hadn’t terminated those decades ago when I started reading about Hardy’s sheep and his ‘oo-arrr’ cast of locals.

What was odd was that it also felt a little like I was killing my reading career. Fulfilling this life goal of completing Far from the Madding Crowd was like admitting to myself that this really was the end. This wasn’t just another book; this was it.

With days to go before the class, as we moved into the second lockdown, I was drawn once again into the landscapes of nineteenth-century Wessex, this time through this long-shelved novel. Locked in, I was reading about wide-open spaces; by lamplight I read about the qualities of sunlight; in the still air of grey rooms, I read about violent thunderstorms and swarms of bees that

swept the sky in a scattered and uniform haze, which now thickened to a nebulous centre: this glided on to a bough, and grew still denser, till it formed a solid black spot upon the light.

Some of the passages seemed so natural as to be unchosen – appearing not so much written as found. It was hypnotic. I was reading like I was falling asleep on the night bus: drifting unconsciously into it before being jolted awake by something teacherly that I had 9to note down. The ‘strong as death’ bit at the end of the book had registered at the time of reading but it drifted away on the breeze of inattention, lost in the commotion of a working day.

vii

A few days later I was out for a walk, trying to sluice my head of the day’s accrued debris, when the ‘strong as death’ line resurfaced suddenly in my memory: ‘Where, however, happy circumstance permits its development, the compounded feeling [of companionship and passion] proves itself to be the only love which is strong as death.’ I did know it.

It was from a poem that we read at school at the same time I had started Far from the Madding Crowd. It was powerful stuff. I remembered being given the verses in class, and as I read them, I wanted to put my hands over the page. It was like the lines were emitting a bright light and I was worried others would see what was written there. I blushed the deceiver’s crimson and sat rigid so as to remain undetected. My fingers splayed on the page, I tried my best to restrain the words from escape.

The poem was by the much underrated and prolific Cornish poet Charles Causley. The Blakean irony of the poem’s title, ‘Nursery Rhyme of Innocence and Experience’, was lost on me at the time. And it does what Causley does best: musicality with complexity masked as simplicity, moving seamlessly from fairy tale to modern war story.

The poem begins with a boy on a quay, asking a sailor to bring him something exotic (a parakeet, an apricot tree) from across the seas. Refusing the proffered penny, the sailor happily consents. Then: 10

And he smiled and he kissed me

As strong as death

And I saw his red tongue

And I felt his sweet breath

‘You may keep your penny

And your apricot tree

And I’ll bring your presents

Back from sea.’

Years pass, and the ship returns, battered and with a hole in its hull. The boy stands on the quay and watches it dock.

‘O where is the sailor

With bold red hair?

And what is that volley

On the bright air?

‘O where are the other

Girls and boys?

And why have you brought me

Children’s toys?’

In the cadence of what seems like a children’s nursery rhyme, Causley captures the ordeals of war, the trauma of time passing, the loss of innocence and the grief of unfulfilled promises.

It was, though, that first erotic aside that punched me in the gut. (‘Erotic’? Really? It is important to remember that adolescent boys are so primed for any kind of sexual experience that a change in the direction of the breeze can register as ‘erotic’.) I had remembered 11the ‘red tongue’ but had long, long filed away the memory of how it had felt to read about a kiss ‘as strong as death’ when there were warnings about AIDS emblazoned across the newspapers.

The whole thing seemed written in Technicolor, but this was no Hollywood musical – more like an Elvis vehicle directed by Derek Jarman. The language is oversaturated, but the sentiment is not. The total effect is oneiric or hyperreal.

My teacher wanted a personal response to the poem. How could I have articulated to him or anyone how deeply the poem had struck me? I relished the exotic language of the ‘apricot tree’ and the ‘parakeet’. I thought apricot was an Angel Delight flavour and I’d never heard of a parakeet. But the resonant nature of the language seemed inextricable from the homoeroticism of it.

Being a gay, closeted kid in the 1980s meant experiencing a queer phenomenology. In it, the very contours of reality were shown to be contingent upon one’s point of view, age, body and desires – real to those experiencing them, imagined to those who only hear of them. In that world, the landscape was different; I saw different things in it, and I experienced those things often at one remove. And growing up in that hostile era has left me with an internalised homophobia embedded so deeply that even in my fifties I am still unable to pull it from its roots. Each time, like a tumour, it just grows back.

It wasn’t that my school was such a terrible place, but as a gay teenager in the mid-1980s from a Catholic family, with Section 28 on the horizon, an AIDS epidemic in full sway, and the age of consent pushed pathologically all the way back to a remote twenty-one years, any and all kinds of sexual difference were in lockdown. I quickly learned it was better not to get too close to anyone, for the simple fact that they might see who you were.

But that poem was a glimpse into another world, an odd, queer, 12fantastical space, and registering the line from it in Hardy’s novel brought the eroticism, the strangeness of it rushing back. And I felt it all again but fondly this time.

viii

I was not alone in seeking solace in other times, places and worlds in those peculiar months of finishing The Hardy Novel. Within days of those first lockdowns across the globe, many of us quickly worked out what our priorities were. It turned out that we really needed four things:

foodhealthcareconnectionstoriesIn those first few weeks, book sales rocketed. As time wore on, Amazon’s UK profits (from sales of all goods) leapt by 51 per cent. In the US they soared, rising 220 per cent with the company pocketing an extra $106 billion in net revenue.2 In India, book sales spiked by around 60 per cent, with comparable rises in Japan, Canada, South Korea, Brazil and South Africa.3 British readers spent an extra £100 million on fiction during the pandemic (a rise of 16 per cent).4 Worldwide, the streaming services cashed in on their newly captive audiences. Thousands of hours across the globe were lost as we slowly, achingly punched our card details into the apps on our TVs to renew our subscriptions. The economics of all this creative output that fills up the streaming services, our gaming consoles, our bookshelves and our walls speaks for itself: creative industries 13generate £111 billion a year for the UK economy. In Australia it’s A$90 billion; in the US it’s $1.1 trillion.5

Within these numbers, buried so deeply that you need to drill down to the dimes and cents, are billions of individuals for whom stories were necessary sustenance.

In 2009, neuropsychologists at the University of Sussex ran a trial which concluded that reading for as little as six minutes can reduce stress levels by 68 per cent. More recent cognitive research has shown that certain kinds of fiction promote empathy in readers. It occurs when readers are exposed to a thing called free indirect discourse – a narrative technique that blends the voice of the narrator with the thoughts and expressions of a character. The effect blurs the line between quotation and indirect narration and it’s often found in writers like Jane Austen and Gustave Flaubert.6

Reading fiction has been shown to quell some of the body’s harmful and toxic responses to isolation and loneliness (reducing levels of cortisol). Losing oneself in stories has been a clinically proven way of alleviating the negative impacts of pain, anguish, depression and anxiety.

But no one is reading books because of the statistics or the health benefits, and the fact that we turn with such frequency to things like neuroscience to justify the habit is indicative of just how much trouble we are in. Mathematics is a means of understanding our world, not explaining the totality of it. People read because it is an act of faith, an act of love. Where Charles Dickens would have expended 900 pages making the point, the American poet Mary Oliver fits the whole idea into a few lines of verse in ‘The World I Live In’:

I have refused to live

locked in the orderly house of

reasons and proofs.14

The world I live in and believe in

is wider than that. And anyway,

what’s wrong with Maybe?

You wouldn’t believe what once or

twice I have seen. I’ll just

tell you this:

only if there are angels in your head will you

ever, possibly, see one.7

Fact will only get you so far. We need fancy too.

Stories are so potent some even call them a technology, invented by humans not to teach us how to make a fire or build a skyscraper but how to deal with loss, how to understand others, how to forge connections, how to be. Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel Beloved, about a family coping with grief and trauma, might, for example, be seen as a means for teaching its readers that trauma must not be buried but incorporated into our world view, acknowledged, otherwise we have no hope of flourishing in the future. Or Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: suppress sexual desire and the force of that suppression will emerge terrifying and uncontrollable. Or Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance: money and class status may buy you some advantage in life, but when it comes down to it, it’s the resilient who survive.

Given what we’ve all been through in recent years and how much diversion we have all craved, it’s no surprise that the turnover and profit of these creative industries is so impressive. Which makes what’s happening to arts education globally as baffling as it is concerning.

‘Creative industries’ broadly refers to those in which the value of the outputs is symbolic: film, publishing, fashion, design, music, gaming, fine arts, architecture. These subjects are regularly offset 15against STEM subjects (for science, technology, engineering and mathematics, though the umbrella also includes medicine and healthcare).* In the education systems of the US, Australia and the UK, as well as those throughout south-east Asia and Europe, governments are flinging money at STEM subjects, stripping it from the arts. Those arts subjects are left to fend for themselves in a supposedly free market, when it’s really one that’s rigged against them.

This is not a new story. Governments all over the world have been clamping chloroform over these subjects for decades and my own discipline of English is no exception. Following a range of telegraphic policies that clearly signal intentions, the flow of students interested in taking arts subjects has been gradually staunched, leaving institutions scrabbling for the few remaining ones. In some parts of the world like Australia, policies have actively disincentivised students from selecting arts subjects, and the student fees are much lower for medicine than literature – even though the cost of the delivery of one is about a twentieth of the other. But while the efforts to stamp out the humanities continue, the students persist in choosing them nonetheless.8 In the UK in particular, individual subjects such as English or History have been made exponentially more boring to endure at school (a subject I’ll come back to in Chapter 5). Ivy League colleges in the US attempt to promote the value of English and the humanities as legitimate alternatives to STEM subjects, but the cost of studying them can in some cases exceed $300,000 across the four years of study.9 In such a situation and with such expense, any student would be remiss if they didn’t ask themselves, ‘How am I going to pay this money back?’

UK students rack up the highest individual debt globally 16(approximately £45,000 per borrower) but, compared to other countries, enjoy a relatively forgiving repayment system… at least, for now. In the US, the debt environment is more heavy-duty. There, the most common repayment plan lasts ten years, so with an interest rate of 6 per cent on $90,000 of debt you will have to find $1,000 every month in the decade after graduation – the time in your career when you are earning the least.

Some might argue that paying for your education is just like taking on another mortgage. Except, it’s not. In the US and elsewhere (the UK, Switzerland, Australia, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, the Netherlands, Canada, Chile, Austria and Hungary), student debt accrues interest at comparative to or faster rates than a mortgage. And with a mortgage, in leaner times you might choose to make some personal economies – perhaps to rent a bit of your house out or sell it and move to a cheaper area. But once you’ve bought your education, you can’t sell it on. Education is treated in many ways like a commodity, like a raw material, but it’s not. Once you have your Ivy League degree (which, if you are on the borrow, would cost about $2,755 a month), how are you going to pay that money back? You can’t trade it. You love books, so you might think you could become an English teacher. It’s an ‘honourable’ profession – but you know as soon as someone deploys that adjective, bad news is in train. As a teacher starting out in the US, you can expect to take home about $38,617; barely enough to cover your loan payments, never mind food, rent, childcare, travel, heating – and not forgetting the tax. It could be worse: some of the teacher starting salaries in Japan, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Estonia, Colombia, Israel, Mexico, Greece, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia or Latvia currently are less than $30,000.10

Equally ‘honourable’ post-English degree careers might see you becoming a copyeditor, journalist, working in publishing or a 17museum. Looked at from this angle, it all seems a bit bleak. None are highly paid, but try to get a job in those industries and you’ll see just how many people don’t care about the salary; they are there because they are utterly in thrall to the work.

Unless you are specifically driven towards these careers, the story goes that you should steer clear of English because you’ll end up an overqualified shelf stacker at a supermarket. (After all, isn’t that the fate I am facing, with university redundancies on the horizon?) But there is a truth that no one wants you to know about the earnings of English graduates. It is a simple and beautiful fact, and you won’t find it mentioned at parents’ evenings or in the press: English graduates aren’t badly paid.

ix

In the UK, the proportion of students studying the humanities has plummeted to 8 per cent from 28 per cent in the mid-twentieth century.11 In the US, the number of those taking English majors has dropped about 50 per cent since the mid-’90s alone, whereas since 2009 the numbers studying computer science or electrical engineering have more than doubled.12 Currently, there are about 530,000 studying business and management in the UK, compared with 15,000 studying English literature.13 Despite humanities graduates having better employment rates, they typically earn a little less.14 English graduates in the US earn a median of $44,600, a couple of thousand below the overall median.15 While STEM graduates have a 3.2 per cent unemployment rate, it’s only 1.2 per cent higher for English graduates.16 The question arises: is a 1 per cent greater chance of your being unemployed a good enough reason for spending three to five years of your life and £60,000 studying something you hate? 18I’m not sure it is. I’d easily take those odds if it meant I never had to do any chemistry ever again.

The answer doesn’t sit in the numbers but in feelings. It’s not that English won’t get you a job, one that you will likely earn a decent wage from; none of the data suggests this. None of it. Anywhere. Instead, it’s the loudly hailed, much repeated belief that this is the case that is making our younger generation think twice. Any parent considering their child’s options has to work against waves of negative supposition – and most don’t have the bandwidth to undertake the fairly deep research needed to find these figures. The belief that studying English leads to low pay is as pervasive as the mist in a steam room, where every molecule of water whispers its hollow mantra: ‘But what job will you get?’

The message is telegraphed from all angles and repeated so often that everyone assumes it to be true. For example, one thing that corroborates, cajoles and creates the disdain with which the humanities are viewed in the UK is the share of central research funding that they receive.

The entire research budget for the UK is divided up across several central funding bodies, among them: nature and the environment, science and technology, medicine, economics and social studies, engineering and physical sciences, and biological sciences. There’s also one for all the arts and humanities. I asked a few people to guess what share of the total budget these subjects might net in the UK. Most of the answers I got bobbed around in the late teens, with the lowest being 15 per cent. No. The total share of budget for over 100 arts and humanities subjects in the UK is 1.4 per cent.17 And it’s shrinking.

As academics, we are regularly prodded by management to chase a share of this money and in doing so, we become greyhounds released from the traps to ravage the hare we already know is a rubber chicken. 19

x

Around the time that I returned to Far from the Madding Crowd, what was most upsetting wasn’t just my circumstances – facing devastating cuts to the department and the likely end of my career – but the fact that it was happening everywhere. All the time. The decades-long assault on the humanities had continued in the background with the persistency of tinnitus. You’d sometimes forget about it, but it was always there.

This particular cut was announced during the squally tenancy of the UK’s then Education Secretary Gavin Williamson, the one with the look of a recently demoted prefect and who resigned before the investigation into the allegations that he had bullied colleagues could conclude.†18 It was the confirmation that the government would, despite objections, be proceeding with more cuts to university funding across the arts. Among the subjects affected by the cuts were archaeology, art, drama and music. Each would have their teaching subsidies slashed by 50 per cent.

When the plans were first announced several months earlier, they received such backlash I naively thought that, unlike the plethora of other cutbacks, these ones might never see the light of day. It was part of the then government’s playbook to make policy announcements and then backtrack. This one stuck, though, and the money saved wasn’t being siphoned into some post-Covid relief fund. Like with other, similar policies, the money was being taken from the arts and humanities and given to STEM subjects. Williamson, who was called ‘the most ignorant, clueless and incapable education secretary in the UK’s history’ by Labour politician David Lammy, 20explained, ‘These changes will help ensure that increased grant funding is directed towards high-cost provision that supports key industries and the delivery of vital public services, reflecting priorities that have emerged in the light of the coronavirus pandemic.’19

The message to senior management in universities is clear: the government does not value these degrees. The message to parents: these degrees are frivolous. The message to students: do these degrees but only if you, or your parents, can afford the debt.

Williamson was eventually sacked as Education Secretary after a staggeringly long two years in post. A train of successors followed, whistling in and out of the revolving doors at the Department for Education. Each of Williamson’s successors was as bemused, uninterested and unqualified as the one before. One of them lasted barely a day in post before resigning – this was enough for her to qualify both for severance pay (25 per cent of a Cabinet member’s annual pay) and a ministerial pension on top of that for her few hours in public service, though she ultimately ended up rejecting both. At least she didn’t make any mistakes during her tenure.

First up was Nadhim Zahawi, who lasted nearly an academic year, from September through to early July. Zahawi was later discovered to have been subject to an HMRC investigation into his tax affairs while he had been Chancellor of the Exchequer (i.e. in charge of the country’s tax affairs), resulting in his having to pay a fine as part of a settlement somewhere in the millions.20 Next up, James Cleverly managed to cling on to the education post for nearly two months. Kit Malthouse, Cleverly’s successor, fared even worse: he only held on for seven weeks. This was clearly a government that did not take education seriously.

Worse still, in the most ‘2022’ move of all, Williamson was rewarded with a knighthood – something that can only be interpreted 21as recompense for something big that the public was not privy to. After all, it cannot have been his performance in the role, which was awash with controversies like the A-level grading debacle, failing to provide guidance or equipment to schools that had to move online during the pandemic, or mistaking Maro Itoje for Marcus Rashford. Labour called the knighthood ‘astonishing and disgraceful’, the Liberal Democrats, ‘an insult to every child, parent and teacher’.21

The message that so many of us are being tricked into broadcasting is that the only thing that matters is earnings, money, profit. Shareholders are king, and it is your boss who gets to say what it is that you need to learn, to know and, concomitantly, to think.

Luckily for all of us, not everyone is so easily duped. For example, instead of blasting off into space strapped to a kerosene-filled phallus, Dolly Parton has used her fortune to distribute nearly 200 million books for children. The economic benefits of Dolly Parton’s charity ‘Imagination Library’ – active in Australia, Canada, Ireland, the UK and the US – has brought unquantifiable social, developmental, educational, personal and emotional succour to millions of children who are learning to love books.

xi

‘Print is dead,’ Egon Spengler claims in 1984’s Ghostbusters. He says the line when the team’s secretary tries to engage him in a conversation about reading. Uber-scientist that he is, he prefers to collect ‘spores, moulds and fungus’.

Ink on paper may seem dead to some, but for others, the blacked-out space on a plain page is the stuff of sorcery. The seventeenth-century poet John Milton also spied alchemy therein, claiming: 22

Books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay, they do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them. I know they are as lively, and as vigorously productive, as those fabulous dragon’s teeth; and being sown up and down, may chance to spring up armed men.22

This is a 1644 version of Stephen King’s wonderfully pithy assertion that books are ‘portable magic’.23 For Milton, books are a vial of distilled intellect; they contain the elixir of genius. The second part of the quotation refers to a scene in Ovid’s Metamorphoses in which Cadmus scatters dragon’s teeth onto the earth and watches armed men grow from these seeds. I love this image of books as tooled-up soldiers ready to fight their cause with their refined concentrate of wit. And it’s also why it breaks my heart that books and ideas are being sidelined in national and international debates, reduced to something that people are free to do but only once they’ve earned the time and money to do it. Plays, drama, theatre and literature, the messages seem to say, are all things that you should be doing for fun, like jigsaws or collecting stamps. But they are not the trimmings of a life. They are life.

It breaks my heart because the thing that I love – all the more so because it got me through the worst parts of my life while also gifting me the best – this thing that has taught me more than I can articulate, this form (the novel) whose job it is to interpret our present, our place in the world, is now treated like it’s being towed for scrap. It’s being taken away from people who don’t even know they need it yet.

I had not the worst but a tetchy start (partly because of what happened to me and my family and partly due to my own selfishness, 23stupidity and inexperience), but I eventually fell in love with English as a discipline. How that happened, where I started and what it did for me are all subjects of this book – and as such, all of those things are about what literature can do for anyone.

A life in literature has afforded me some terrific opportunities. It’s taken me to corners of the world that I could never have seen without it. It’s made me the person that, through it all, I wanted to be and hoped I might become. It’s gifted me a kind of stability that I could only see elsewhere when I was growing up. It’s taught me that reading isn’t just a means of learning how to navigate the world but it’s also about finding one’s place in it. How many activities result in you getting to change your name… twice? From Mr to Dr, then Dr to Professor?

It has changed the way I see the world. It has changed the way in which I understand it. It has taught me to write, to think, to look and look again. Now, when I finish a good book, the loss I might feel at leaving that world is suddenly offset by the giddy excitement that I can, in a matter of seconds, go anywhere and anywhen. Inside the piles of books I have around me as I write are civilisations, cities, histories and futures, challenging you to look upon them and not despair, because you are never lonely when you are reading. The activity suspends you in a web of relations between your present and your past, between you and the voices of the page, between you and the bustling lives of those you meet there. Finally, reading sits at the centre of your being and, like a force, pushes itself into your thoughts, your actions and your life. It’s as enigmatic as it is powerful.

Reading offers a kind of freedom that cannot be garnered any other way. Its value cannot be implied, only inferred; it cannot be instructed, only constructed; it cannot be given, only received; it cannot be shown, only made; it cannot be taught, only caught. No 24amount of computing power can download or process it for you; no one can be paid to do it for you. You can’t copy it from someone else. No amount of money can buy it – its miracle is that it may only be acquired in the doing of it. Literature becomes you.

Now, are you sitting comfortably?

xii

What follows in this book is my own story of transformation through reading. When I had the idea, I originally wanted to write a paean to reading, but the assaults on its value and contribution took over. So, on our journey, I will burrow down into the specifics of the books that have mattered to or changed me most and what they continue to do for others. But it’s not just about me: I present my reading story here alongside the story of the recession of the humanities and the study of English literature because I think it shows the future-changing power that reading has, as well as the things that it’s able to do and to achieve.

We are going to disinter some of what has happened to English, from primary through to tertiary. I want to show you a little of what it is that people do when they ‘do’ English and a little of what it’s like to be an academic – not too much though because it’s mostly emails and meetings so stressful the participants’ jugulars visibly throb. I want to tell you about what happens in universities, what they are trying to do and why it matters. I want to show you some of the artful and wrongheaded ways that English is being destroyed, and I want to do it by showing you what it did for me.

While reading might appear to be a solitary activity, it is in fact a companionable one. Books, as we will discover, can have similarly beneficial outcomes to our wellbeing as powerful as meeting up 25with friends. And, just like our friends, they change as we do. The best of them stay with us and, like an ageing face, their pages take on a certain pallor, they develop fine creases and wrinkles, but what they mean to us changes and matures, too. This is their magic.

In Hardy, there always has to be a little tragic irony. When I finished the novel, I felt like I had lost something, like a relation. In the past, the book was an open field to me. In my imagination, I would regularly breeze past it, the gate to it would be wide open, the grass would be winnowing in the breeze – there would likely be a few sheep in there too. Now, thirty-seven years on, it’s all fenced up and cordoned off. Far from the Madding Crowd is finally back on the shelf with thousands of other books marked as ‘read’.

There’s a line in the book I came across while reading it: ‘He had been held … by a beautiful thread which it pained him to spoil by breaking.’ I underlined it and reflected on the fact that I should have thought more deeply about closing the oxbow in time that that novel represented. While it also inspired me to reflect on where I had come from, for me Far from the Madding Crowd was, more than any other book, what ‘English’ was and what it stood for. Here I was, at the other end of my career, looking down over the balustrade at all that had been done in recent years to muffle its voice, to denigrate the creative and critical thought it fuels, to devalue the nuanced reading it stimulates, and ultimately to sideline its tremendous and transformative power for conveying a simple and organic truth: you are not alone. You never were.

Notes273

1The Scientific Century: securing our future prosperity (London: The Royal Society, 2010), p. 14.

2 ‘Annual net sales revenue of Amazon from 2004 to 2023’, Statistica.com, 1 February 2024, https://is.gd/0JEsVF accessed 10 May 2024

3 Mayank Tiwari, ‘Stay home, stay well-read: Pandemic drives book sales in twin cities’, New India Express, 11 April 2021, https://is.gd/8i76V9, accessed 21 December 2023; Tauseef Shahidi, ‘Pandemic a boon for books, bane for bookstores’, Mint, 16 September 2020, https://is.gd/7CEyFn accessed 21 December 2023.

4 ‘Publishing in 2020’, Publisher’s Association, 27 April 2021, https://is.gd/DxWj3a accessed 10 May 2024

5 ‘“Projects”, Australia’s creative industries: valuation’, SGS Economics and Planning, December 2013, https://is.gd/UXtSbL accessed 21 December 2023; ‘Creative Economy Contributes over $1.1 trillion to the US Economy’, National Assembly of State Arts Agencies, 25 March 2024, https://is.gd/PryIRM accessed 10 May 2024.

6 Angus Fletcher and John Monterosso, ‘The Science of Free-Indirect Discourse: An Alternate Cognitive Effect’, Narrative, 24:1, January 2016, pp. 82–103.

7 Mary Oliver, ‘The World I Live In’, in Devotions: The selected poems of Mary Oliver (New York: Corsair, 2019), p. 5.

8 Caitlin Cassidy, ‘Students choose arts degrees in droves despite huge rise in fees under Morrison government’, The Guardian, 13 April 2024, https://is.gd/a3eXNw accessed 9 May 2024.

9 Daniel Kurt, ‘What Harvard Actually Costs’, Investopedia, 7 August 2023, https://is.gd/aUvQeF accessed 10 May 2024.

10 ‘Teacher Salary by Country 2024’, World Population Review, https://is.gd/F1BDSq accessed 10 May 2024.

11 Will Hazell, ‘University courses: number of students taking humanities subjects is down 40,000 in 10 years’, The i, 23 September 2021, https://is.gd/GNugRu accessed 10 May 2024

12 David Laurence, ‘The Decline in Humanities Majors’, The Trend – Research and Analysis from the MLAOffice of Programs, 26 June 2017, https://is.gd/ORrlHo accessed 21 December 2023; Benjamin Schmidt, ‘The Humanities Are in Crisis’, The Atlantic, 23 August 2018, https://is.gd/aXarqA accessed 10 May 2024.

13 Eleanor Hopkins et al., ‘English Studies Provision in UK Higher Education’, The British Academy, June 2023, p. 27, https://is.gd/AClzxT accessed 10 May 2024.

14 Oxford Learning College, ‘The UK Degrees With the Best Earning Potential’, https://is.gd/OdfzYZ accessed 21 December 2023.

15 ‘Employment Outcomes of Bachelor’s Degree Holders’, The Condition of Education 2020, National Centerfor Education Statistics, https://is.gd/d3wBI7 accessed 10 May 2024.

16 Ibid.

17 The AHRC gives £110 million of funding to projects each year. The total UKRI funds are in excess of £8 billion. See ‘Who AHRC is’, UK Research and Innovation, 28 November 2023, https://is.gd/0KsG4a accessed 10 May 2024; ‘Geographical Distribution of UKRI Spend FY 2019–20 and FY 2020–21’, UK Research andInnovation, p. 7, https://is.gd/4ayTWH accessed 10 May 2024 274

18 Sophie Thomas, ‘Prime Minister’s Questions: Rishi Sunak says it is “absolutely right” Gavin Williamson resigned – and admits “regret” over appointment’, Sky News, 9 November 2022, https://is.gd/ndomc1 accessed 21 December 2023.

19 Aubrey Allegretti, ‘Gavin Williamson apparently confuses Maro Itoje with Marcus Rashford’, The Guardian, 8 September 2021, https://is.gd/se7mi0 accessed 21 December 2023; Sally Weale, ‘Funding cuts to go ahead for university arts courses in England despite opposition’, The Guardian, 8 September 2021, https://is.gd/isk51s accessed 10 May 2024.

20 Anna Isaac, ‘Nadhim Zahawi “agreed on penalty” to settle tax bill worth millions’, The Guardian, 20 January 2023, https://is.gd/sUElv6 accessed 21 December 2023.

21 Andrew Woodcock, ‘Gavin Williamson knighted six months after losing cabinet job following exams fiasco’, The Independent, 3 March 2022, https://is.gd/se7mi0 accessed 10 May 2024.

22 John Milton, ‘Areopagitica’, in