1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

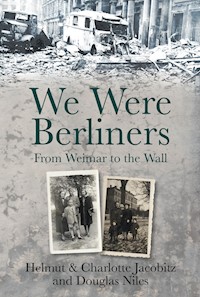

Helmut and Charlotte Jacobitz were born in Berlin during the mid-1920s. They experienced depression and inflation, and witnessed violence as fascists and communists vied for control of Germany. When the Nazis prevailed, they survived the 12 years of the Third Reich. Drafted in 1943, Helmut was wounded fighting in Normandy. Charlotte, meanwhile, worked at the Reichsbank and took shelter against frequent bombing raids. After the Russians surrounded Berlin in April 1945, she witnessed firsthand the brutal battle for the city. The two young Germans met each other after the war, Charlotte joining Helmut to smuggle food into Berlin through the Russian blockade. The family finally immigrated to America, barely escaping before the Berlin Wall sliced the city in half. We Were Berliners combines the personal reminiscences of the Jacobitzs with a lively, detailed overview of historical events as they related to the family, to Germany, and to Europe.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

For our family, and for Berlin

– Helmut & Charlotte Jacobitz

For my father, Donald Niles,

who brought me up to love the stories history has to tell

– Douglas Niles

Contents

Title

Dedication

Preface

Maps

1A Republic, Stillborn

2Under the Swastika

3A Nation Resurgent

4Blitzkrieg

5Fallschirmjaeger

6Bull’s Eye on Berlin

7The Normandy Campaign

8Million Dollar Wound

9Battle for Berlin

10War’s End and Home

11Aftermath

12A Cold War Courtship

13Blockaded and Betrothed

14To the West and the Wall

Epilogue

Plates

Copyright

Preface

I didn’t know Jason Jacobitz when he telephoned me one day in 2009 with an interesting proposition. Throughout his life the young Californian had listened to his grandfather, Helmut, talk about his experiences during the Second World War, and Jason wondered if those remembered stories might form the content of a book. Helmut, now a German-American in Los Angeles, was a Berliner by birth, and had been drafted into the Luftwaffe – the German air force – during the war.

Although he hoped and expected to become an aircraft mechanic, Helmut had instead been given a rifle and was informed that he would be a paratrooper. His subsequent path took him to Normandy, France, where he and his battalion arrived shortly after several hundred thousand British, American and Canadian soldiers had pushed their way on to the European mainland over the D-Day beaches.

The genesis of this book, as much as anything, is Jason’s determination to see the story told. I learned that he picked me as a co-author because he’d enjoyed one of my adventure novels, a story written nearly twenty years ago; and that he’d been disappointed with the several experienced ghostwriters he’d already interviewed. In his frustration, I gather that I became something of a last resort.

The idea of the book was intriguing to me, and I leapt at the opportunity. I have always been fascinated by the history of the Second World War, and have written numerous articles and designed several military simulations on the topic. The chance to tell the true story of a man who had been there was irresistible. We agreed that Jason would record extensive conversations with his grandfather, send me the recordings, and I would turn the interviews into an autobiographical narrative.

Jason started the project by spending several weekends at his grandparents’ kitchen table, listening and recording while they both reminisced, and a funny thing happened. Jason and I realised that this is not just a Second World War story – in fact, it is not just Helmut’s story. For one thing, Helmut’s wife (and Jason’s grandmother) Charlotte was every bit as much of a Berliner as Helmut. She, too, had a compelling story of her experiences during the war years. (During one of the interviews, an astonished Jason tells her ‘You saw more of the war than Grandpa did!’) Secondly, the Jacobitzs were present for many of the most significant events of modern German and European history, events that occurred before, during and after the Second World War.

Berlin is far more than just the largest city in, and the capital of, Germany. It is a symbol of German history, pride and hubris; and it has paid the price, in spades, for its part in that history. It is the place where Hitler seized power; where the Nazis planned their most dastardly acts; where the Allies – Britain and the United States through the air, the Soviet Union on the ground – took their ultimate revenge against the Third Reich; and the place where the Cold War became focused like a laser beam, and very nearly turned hot. Finally, when the Communist Empire collapsed like a house of cards, Berlin was the first and most crucial card pulled from that deck.

So the book expanded to become the story of both Jacobitzs, from their childhoods, through the war, to marriage and parenthood and eventual emigration. And it expanded again when we realised that the story called for context, for historical perspective of events occurring beyond the immediate scope of Helmut and Charlotte’s lives and memories. To that end, I have framed the autobiographical sections with passages in the mode of popular history, so that the personal events are placed against the backdrop of epic happenings.

For more than a year, Jason made many trips from San Diego to Los Angeles to interview his grandparents, compiling dozens of hours of recordings, ferreting out details long buried. Occasionally his cousin Nicholas would join him for the recording sessions.

Near the end of the writing process, I travelled from Wisconsin to Los Angeles to meet and be charmed by the Jacobitzs. They are in their mid-eighties now, but they were energetic and personable as we chatted at their kitchen table, in a beautiful home high in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. We talked for hours on end, several days in a row as they shared with good humour and insight more of their experiences, answering my questions and filling in the blanks of the story. They both speak English well, but when they put their heads together to discuss, in German, some aspect of the story they recalled from different perspectives, a listener gets a clear picture of the Berliners they were, and will always be.

To transcribe the recorded interviews I used the able assistance of Andrea Roberts, a young lady whose accurate transcripts became my invaluable working tools. She put in many hours with headphones on her ears and keyboard at her fingertips, wrestling with German terms and, occasionally, Helmut’s accent, as she created the clean, crisp copy that made my job immeasurably easier.

Another fortuitous occurrence moved us forward when my friends Matt Forbeck and Stephen Sullivan put me in contact with their associate Steven Savile, who in turn connected me with Jay Slater, at The History Press. Jay embraced the concept of the book from his initial look at the idea, and has been an enthusiastic supporter in moving this project toward publication. My good friends of the Alliterates Writing Society have also been very helpful, as always, in listening to sample sections read aloud, and providing me with astute criticisms. Stephen Sullivan gave me further help when he rendered my two hand-drawn maps into the versions published in this book.

However, mostly this book exists because two wonderful people were willing to share their story with the world, and because they had a grandson who cared enough to make sure that it happened. To all the Jacobitzs, I can only say thank you, and it is a privilege to be involved in your story.

Douglas Niles

Delavan, Wisconsin

Maps

1

A Republic, Stillborn

My father pushed me along in my stroller, running as fast as he could. Fascists and communists were shooting at each other right down the street, and he was terrified. I was too young to be frightened. He told me later that I laughed and clapped my hands the whole way home.

– Charlotte Jacobitz

The First World War’s four-year cannonade finally faded into silence on 11 November 1918. The Great War left a continent shattered, battered and exhausted from the struggle that had commenced in August 1914. An entire generation of young men had been sacrificed on the altars of barbed wire, machine guns and poison gas. A communist convulsion had transformed Tsarist Russia into the fledgling Union of Soviet Socialist Republics; in 1918, that vast nation remained locked in a bloody civil war.

The Allied nations of Britain, France, Italy and the United States had emerged bloodied but victorious. One half of the defeated Central Powers, Germany’s erstwhile ally in the First World War, had been the long-standing Austro-Hungarian Empire. With the final defeat, that empire simply ceased to exist. At war’s end the sprawling monarchy, also remembered as the ‘Habsburg Empire’, which had always been made up of feuding ethnic minorities, was broken by the victorious Allies into newly formed nations, including Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Austria, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania and Yugoslavia.

Even the major European victors of that awful war, Britain and France, staggered out of the conflict weary and exhausted. Only one of the powerful Allies, the United States, had emerged from the war with population and territory relatively unscathed. And the US had been a latecomer to the conflict. Following numerous sinkings by German U-boats of merchant ships in the Atlantic, the American Congress finally declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. The entry of the USA had proven decisive in Europe, but damaging in the New World as the American government subsequently fell into the hands of isolationists who wanted nothing to do with the troubles ‘over there’.

However, in all the terrible aftermath of the conflict that was termed ‘the War to End All Wars’, no single nation, no people, had suffered as much and been as soundly punished as Germany and the Germans. Under the autocratic rule of the monarch Kaiser Wilhelm II and his powerful industrialist advisers, the nation had committed some 11 million men – 18 per cent of the population – to the struggle by the middle of the war. About 2 million of these men died in a conflict that exhausted the country physically, emotionally and financially. By the winter of 1916–17, Germany was virtually out of food, with civilians subsisting near starvation levels.

In the last year of the war, the German army had tried a new tactic, employing elite storm troopers in small units to infiltrate and finally break through the stalemate of the trenches in spring 1918. By then, however, the nation lacked the men, ammunition, equipment and economic power necessary to exploit that breach. As new machines like tanks and aircraft flexed their muscle on the battlefield, Germany didn’t have the resources to produce enough of these modern weapons to matter. When American troops began to arrive in Europe in great numbers – eventually some 2 million ‘doughboys’ would be deployed to France – the tide turned for the last time.

In late summer 1918, Germany faced revolts among the working class and mutinies in the armed forces. Beginning with the navy, the Kaiser’s troops simply refused to fight. Facing the inevitable, Wilhelm II abdicated his throne and the de facto rulers of the nation, Major Generals Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenburg, finally gave up the struggle. It was Ludendorff and von Hindenburg who had decided to embark upon the total unrestricted U-boat war in the Atlantic – authorising submarines to sink, without warning, any ships they encountered. They gambled that to cut off supplies to Britain and France would offset the certain entry of the USA into the war. It was a gamble they lost.

As a national power, Germany had marched on to the world stage much later than centuries old states such as England, France and Russia, all of which had possessed a national identity for a thousand years or more. With the Teutonic states, it wasn’t until 1871 that a confederation of monarchies, duchies and baronies – aligned by culture, language and ethnicity to the militant and powerful state of Prussia, with its capital at Berlin – was forged into the German Empire. That empire’s course was planned and plotted by the iron will of its first chancellor, Otto von Bismarck.

Although she arrived late on the scene, Germany wasted no time in trying to catch up to the rest of Europe. Since Prussia had trounced France, Russia and Austria in a series of short, dramatically successful wars, Bismarck proceeded to secure his nation’s place in the first rank of the world’s Great Powers. In the 1870s and 1880s, Germany became a leader in diplomacy, defusing several potential flashpoints between Turkey, Russia and the rebellious Balkan states of the slowly withering Habsburg Empire. German factories powered forward with industrialists gaining ever-increasing influence until the country was producing more armaments than any European rival. Krupp steel became the benchmark of high-performance metal, and Krupp gun barrels were known to make the best cannons in the world.

Bismarck’s influence waned in the last decade of the nineteenth century as Wilhelm II, the son of the original emperor, secured more power for himself. Adopting the title of ‘Kaiser’, young Wilhelm was a bellicose and insecure wildcard on the international scene, one who was determined to dominate European politics. He maintained the alliance with Austria-Hungary originally forged by Bismarck, but regarded the other major powers as distinct rivals.

Naturally, Tsar Nicholas II – virtual dictator of Russia – and the parliaments of Britain and France regarded the German rise with alarm. All of these countries devoted huge segments of their economies to armaments, and when 1914 rolled around the various empires were armed to the teeth, and each was confident of ultimate mastery. By the time a Serbian terrorist assassinated Archduke Ferdinand, the heir to the Habsburg throne, in Sarajevo, Europe was on the fast track to war.

The specific causes of the First World War were complex and will forever remain controversial; suffice to say that the conflict had become virtually inevitable. Too many nations had invested too much money and influence on modern arms and industrial development. Too many leaders were utterly convinced of their nation’s own physical and moral superiority, and of the vulnerability and venality of their rivals. During the years of bloody conflict, the mobility provided by extensive rail networks and the lethality of machine guns, barbed wire and poison gas dramatically increased the horrors of battle, raising the carnage to previously unimaginable levels.

There is no debating the outcome, however: the Germany of Kaiser Wilhelm had been defeated, worn down to a state of economic ruin, forced to sign a humiliating treaty to end the hostilities. The Treaty of Versailles, inflicted upon Germany by a vengeful tandem of Britain and France, would leave wounds that would only be closed after another, even more destructive, war.

My father had been a German soldier in World War I, but he never talked about it. We all knew it had been a very dark time, and like most other Germans he wanted to forget about it.

I was born on 10 February 1926, the last of my father’s four children. My oldest brother was Hermann, and he was around 10 when I was born; my next oldest brother was Karl, and he was six years older than me. They were the sons of my father’s first wife.

She died when Karl was 2 years old. She was pregnant again, and times were really hard so she didn’t want to have another child. She tried to have an abortion – on the black market, like in an alley. They used something that I heard was called ‘black soap’, maybe glycerine, and it killed her. That was in about 1922, which was a really bad time for Germany.

So then my father married my mother, Anna Weber, who was about nine years younger than him. She had my sister Gretel, and then two and a half years later she had me, Helmut. My brother Hermann had a lot of trouble adjusting to a new mother. He was at a bad age to lose his own mother, and he never really accepted my mother in her place.

We lived in a Berlin neighbourhood called Prenzlauer Berg. It was an older area, just north and east of the city centre. The Tiergarten Park, for example, was about 4 miles away. The place where we lived was middle class, but kind of low. Still, it was better than the lower-class areas. People were employed, and many of them had salaried jobs.

It was getting a little better when I was born than it had been during the First World War and right after. I remember hearing that during that war they used to make everything out of cabbage – that’s how people stayed alive. I guess they even made coffee out of cabbage! We learned about that war in school. They didn’t tell us that Germany was good or bad in the war, just that the prince from Austria got shot in Sarajevo.

My father was a Buchstaben Klempner, a ‘sign hanger’, which was a very specific job in the sign business. There were several companies involved in each sign. The first was the sign painter, who does a drawing, in colour, of the sign. Those drawings go to the sign maker – that was my job when I was older – who cut out the pictures, usually from pieces of sheet metal.

And then there was the guy who mounted the signs on the posts or buildings or towers or whatever. That was my dad. In fact, it was kind of his dream that someday one of his sons would make the signs that he hanged. He owned his own business – he even did some work in the United States for a while, when I was a boy. He never really talked about it, except to say that everyone had a car in America – too many people had cars!

In Germany, things had been tough for the years after the first war. There was a flu epidemic right after the war ended that killed millions of people. I guess more than 1,000 people died every day, just in Berlin.

And when that passed, there was still no money. Inflation was terrible. I heard about people who got paid on Monday and right away went to cash their pay cheques – because they would only be worth half as much by Friday! So you would earn your money, and then stop at the shop or market right away to spend your earnings, since they’d be worth only half as much, maybe less, by the next day.

When I was little, before 1933, people still used to go and vote. They would go to the pub to vote, and I remember the Nazis in their uniforms, carrying their swastika banners, would be outside the pub with their signs and they’d push people pretty hard to vote for the Nazis. At that time, the economics were still pretty lousy, with lots of unemployment. Those guys were called the Sturmabteilung (storm troopers); but we all knew them by their uniforms as the ‘brownshirts’, and they were really just a bunch of bullies. But they marched and were loud, and were pretty frightening.

Some people voted for the Nazis because they believed they would do something about the terrible times and the tough economy. At that time we were still supposed to be paying a lot of money to Great Britain and France. The Nazis said, ‘No, to hell with that! We’re not paying!’ They played on people’s feelings, like the deal that the treaty after the First World War was really unfair to us. They always claimed that Germany was destined to be a great country, and they also blamed the Jews for just about everything that was wrong. They were blaming Jews from the very beginning.

I think that’s partly why inflation got so bad, because of that money Germany was supposed to pay. But the country didn’t have the money, so they just started printing more and more of it. When 1-mark bills didn’t have any value they’d print 10-mark bills, and then 100 marks, and 1,000, and so on.

They didn’t win those elections in the 1920s, but when there got to be more Nazis they would march through the street in their uniforms, with their flags waving. Everybody was supposed to salute the flag. If someone refused to salute, a couple of guys or maybe even more in the front of the parade would come over and beat up the person who didn’t salute.

– Helmut Jacobitz

The Legacy of Versailles

It was on ‘the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month’ (11 November 1918) that the treaty was famously signed in a railway carriage parked on a siding in Versailles, France. The Treaty of Versailles ended the First World War at last, and it imposed sanctions of unprecedented harshness on defeated Germany. The repressive and humiliating settlement would leave vicious scars in the national pride of the German nation, scars that would neither be forgotten nor forgiven. In fact, when the Nazis forced the surrender of France in 1940, Hitler would require his enemies to submit to him in that very same railway carriage.

The victors , naturally enough, blamed the losing side for the war, though an objective observer can see that there was more than enough blame to go around. Not surprisingly, the treaty required that Germany make territorial concessions – to France, Poland and the newly created nation of Czechoslovakia, most notably (see Map 1). France made good on her losses in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, reclaiming the territories of Alsace and Lorraine; these provinces lay on the southern edge of the border between France and Germany, and had been the focus of conflict for many centuries. They would remain so for several more decades, and as the Nazis rose to power the grievance with France would frequently be cited as a gross indignity. Another part of Germany, the Sudetenland, was torn away and given to Czechoslovakia. This enforced change, too, would provide Hitler and the Nazis with a strong rallying cry for justice and retribution.

Probably the most galling change in borders from the German point of view occurred when the Allies restored the nation of Poland as an independent state. Poland had been fought over and divided by Prussia and Russia for a very long time, but it remained a national entity with its own language and a sense of identity that demanded independence. The restoration of Polish sovereignty rankled the Russians as much as the Germans, but as that great Slavic state was still engaged in its own civil war in 1918, one that would soon see Lenin’s communists victorious, the eastern power did not have a strong voice in the settlement details. Since it was deemed right that Poland have access to a major port – the city of Danzig – East Prussia was split from the rest of Germany, leaving a gaping slash in the country that before long would provide the most powerful fodder for Hitler’s ambitious, nationalist proclamations.

German overseas colonies were stripped away, with her African colonies going primarily to Britain and her islands in the Pacific, notably the Gilbert and Marshall chains, handed over to Japan – which had been aligned with the Allies in the Great War. The latter provision was one that the Americans, in particular, would come to very much regret since, when the Second World War began, those islands had already been developed into powerful Japanese bases.

Further restrictions were designed to keep Germany from ever becoming a great military power. German troops, army and air installations were banned from the Rhineland – a large German province west of the Rhine River and adjacent to France. The defeated nation was limited to an army of only 100,000 men, with a drastically curtailed navy. She was not allowed to build or operate submarines, military aircraft or tanks. As a final nail in the coffin of German militarism (or so it was hoped) the German General Staff, developed from the Prussian model and the clear gold standard for all professional militaries in the world, was ordered to disband, never to be formed again.

The treaty was rounded out with some so-called ‘honour clauses’, designed mainly to humiliate the defeated nation. Germany was forced to admit responsibility for starting the war – a ‘fact’ that was debatable, at best – and to pledge to make financial reparations to the victors. These reparations, if fully enforced, would have placed Germany in a state of abject poverty for the foreseeable future.

Despite the harsh terms of the treaty, the nation began the post-war period with a very modern constitution. The traditional aristocracy, long rulers of the hodgepodge of territories making up Germany, knew that a king or emperor would be unacceptable to an increasingly modernised populace. They settled for a constitutional republic, established in the city of Weimar (hence the ‘Weimar Republic’, as it would be known in later years), in which a great deal of political power remained in the hands of the wealthy aristocracy, but a lower house, the Reichstag, would be populated by lawmakers elected with nearly universal suffrage.

At the same time, the victors in the Great War were already bickering among themselves. France and Britain had ever been historic rivals; and Russia was going through a complete transformation of government and society. Each was proud of its own place, and suspicious of all potential rivals. One of the leaders among the Allies, American President Woodrow Wilson, presented a visionary plan of ‘Fourteen Points’, including a proposal for the establishment of a League of Nations, an international body to mediate differences. Though the European countries eventually adopted the league, Wilson suffered a stroke and became an invalid before he was able to convince conservative American senators to ratify the treaty required for US participation. These early isolationists essentially killed the League of Nations even as it was created, for without American involvement it could never be more than a symbol.

Even so, the German people, hungry, defeated and humiliated, did not prove easy to govern. The years 1920–23 were wracked with turmoil, as communists struggled to gain power and conservative elements, many of them ex-soldiers, organised right-wing militant groups called Freikorps and acted violently and ruthlessly to repress the liberal and socialist elements of society. During the early years of the twenties, inflation raged out of control, and the country veered from one extreme to another.

I was born on 31 January 1927. I soon had two younger brothers, Paul and Gerhard. I was the oldest, with Gerhard coming eleven months after me, and Paul four years younger. Together with my parents we lived, the five of us, in a small apartment in Berlin. The neighbourhood was called Berlin Wedding, and it was a lower-middle-class area – mostly what we would call ‘blue-collar workers’. My parents were Paul and Martha Wolff; my mother’s maiden name was Kirchoff.

Wedding is just north of the heart of the city, and just west of Prenzlauer Berg. It was known for having being an area with many residents who leaned toward the communists. There were a lot of Catholics living there, and also a lot of Jews – later, it was one of the areas that suffered a lot when the Nazis did all that damage during the Kristallnacht.

The apartment we lived in was really tiny, but it did have a decent-sized kitchen, which made it a nice place compared to a lot of others in the same neighbourhood. I slept in the corner of the kitchen. There was one other room that was the living room and bedroom together.

It was small, but better than the neighbours’ place! They just had one room; the kitchen was in the same room as the rest of the space. It was a neighbourhood of working people, mostly pretty poor. You had to be rich to have a big apartment. All kinds of people were mixed up together. I wouldn’t want to show it to my family now – they would think ‘Oh my God, where did my grandmother come from?’

Later, because our last name, Wolff, sounded like it might be Jewish, we were worried about trouble from the Nazis. So my father looked up to find out where our forefathers came from. His father was Polish – he was an architect, and I heard that he designed many famous buildings in Poland. He, my grandfather, was disinherited from his family because he married a woman who was not wanted in the family.

And maybe his family was right about that woman! I don’t know why they didn’t want him to marry her, but he married her, they came to Berlin, had six children, and then he drank himself to death. That was my father’s father – he drank himself to death when he was 42 years old. I never knew him.

I did meet my grandmother, his wife, once. She died when she was 70. Her name was Catarina Piotrowvich. It sounds Russian, but it’s a Polish name.

I remember meeting her for a very good reason: my mother took me to see her on my birthday, when I was 5 – so that would have been 1932, almost a year exactly before Hitler came to power. My grandmother gave me a bar of chocolate for my birthday. You didn’t see much chocolate in those days. My mother told me to take the chocolate home and share it with Gerhard. Now, I really loved my little brother, but I said, ‘No – I want to eat all the chocolate!’

And Catarina said, ‘Let her eat the chocolate, it’s her birthday.’

So I’ll never forget her. I can’t remember what she looked like, but she let me eat all the chocolate. And of course, I got sick! Even then I felt sorry that I didn’t share it with Gerhard; and of course, after what happened to my little brother after the Nazis took over, I have felt guilty about that chocolate for the rest of my life.

That’s about all I remember about my grandparents. My father worked pretty hard. He had a job in a factory, at least for a while. But he was still working in 1928, 1929. By that time, the communists and the fascists were already fighting. The Nazis had started in Bavaria and were not popular in Berlin, which was more full of communists than fascists. But by the time I was a few years old the Nazis were getting more powerful, and they would battle right in Berlin.

There were several times I heard about this happening: gunfire would start up nearby when I was out with my dad on some errands, or for a walk. My father pushed me along in my stroller, running as fast as he could. Fascists and communists were shooting at each other right down the street, and he was terrified. I was too young to be frightened. He told me later that I laughed and clapped my hands the whole way home.

That happened more than once! He said I loved it, that I was laughing my head off because I wanted him to run.

He didn’t work in that factory too long because he got lead poisoning, and couldn’t work. He was sick for many years, and for a lot of that time he couldn’t even walk. He was in the hospital for a long time. They were going to open up his brain, but he wouldn’t let them do that. He put on his pants and his coat and somehow he walked out of the hospital and went home.

But he couldn’t work, so he was sick at home. My mother collected welfare, which I guess was about 14 marks a week. I remember that our rent was 20 per month, and we had to pay for electricity, coal for heating and food also out of that.

My father could be stubborn, but really he was quite a softie. He was very affectionate with us children, and, maybe because he was staying home so much, he did a lot with us. My mother was the opposite: I would say she was kind of hard. She was unhappy about a lot of things in life, and she had a bad temper. She had a paddle, with seven leather straps hanging off of it – it was called a Seibenstream – and she would use it to spank us. She used it so much that the leather straps wore away!

I got sick, when I was about 5 years old, with diphtheria. Near our apartment there was this big hospital, called the Kinder Hospital. They had a lot of good doctors there. This was before the Nazis took over, when I got sick and went there. The doctors put me in a glass room, a sterile room, all by myself. Visiting time was for one hour each on Wednesday and Sunday, and my Mom could come and only look at me through the window. I got chicken pox when I was recuperating from diphtheria, but I got better, and after four or maybe six weeks they let me go home.

– Charlotte Jacobitz

A Storm Out of Bavaria

In south-west Germany, aligned beside Austria and Switzerland, the province of Bavaria had long been a remote and conservative counterweight to the prosperous and technologically advanced nation of Prussia. Bavaria’s great cities, including Munich and Nuremberg, were more old fashioned and traditional than modern, cosmopolitan Berlin. In fact, with its heart in towns and small villages, and the Alps at its back, Bavaria was as far from Berlin both culturally and physically as it was possible to get without leaving the country. Bavaria is a realm of dark, impenetrable forests – think the Brothers Grimm – and of fairy-tale castles, of Alpine foothills and boisterous beer halls.

It was in Bavaria that the scattered organisations known as the Freikorps, militant groups made up primarily of angry and bitter First World War veterans, began to coalesce around what would become a single leader and a single party. The nationalist movement began with the deep-seated belief that Germany had been badly wronged by the Treaty of Versailles, and that the country was destined to regain its ascendancy. The most prominent of these Freikorps was called the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (DAP, or German Workers’ Party) and it was rallied by the words of a fiery speaker named Adolf Hitler.

Ironically enough, Hitler – who would become known as the vocal proponent of the Aryan, purely German, ‘master race’ – was not German at all, but rather an Austrian, from Vienna. His family moved to Bavaria when he was a young boy, and he grew up speaking the (low) German dialect of the province. He spent some time at a school run by monks, where the walls were inscribed with many images of a cross with each of the bars turned at a right angle; later, he would use this symbol for his party, and the world would come to recognise it as the Nazi swastika.

He served with the German army in the Great War as a mere corporal, and by all accounts he was courageous on the battlefield as he performed the unusually dangerous role of a military courier. In 1914 he earned an Iron Cross (Second Class) for bravery, which was followed by the Iron Cross (First Class) in 1918, Germany’s highest award for military bravery, very rarely bestowed upon a soldier ranking as low as a corporal. During the course of the war Hitler fought in major engagements, including the First Battle of Ypres and the battles of the Somme, Arras, and Passchendaele.

Following the war he settled in Munich, where he became one of the early members of the group initially known as the German Workers’ Party (DAP). He participated in the smashing of the Bavarian Socialist Republic, a fledgling provincial government that vanished as quickly as it had arisen, and by 1919 Hitler was embracing a right-wing agenda that blamed Germany’s problems on the Treaty of Versailles, and a vast conspiracy perpetrated by ‘International Jewry’.

Always a fractious organisation, the DAP wavered between socialist and fascist leanings. Hitler’s influence, supported by his matchless oratory, soon made him the most important and influential member of the party. When the socialists made an attempt to take control, he threatened to resign, and the members realised that his absence would effectively mean the end of the party. After a vote of 543 for Hitler, one against, his position as leader of the DAP was secure.

In April 1920 the party was renamed the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers’ Party), commonly shortened to ‘Nazi’ Party. On 29 July 1921 Hitler was installed as the absolute leader, or Führer, of that party. He continued to speak and gather supporters using Munich’s ubiquitous beer halls as his auditoriums. His speeches focused bitter accusations against Jews, social democrats, monarchists, communists and capitalists; and these attacks resonated with many of the most bitter and humiliated of the German people.

The Nazi Party grew steadily in membership and influence, attracting some famous members, such as the former air force fighter pilot Hermann Göring and a captain in the army named Ernst Röhm. Röhm soon became the leader of the Nazi street army, called the Sturmabteilung (SA). Distinguished by their brown shirts and their unified, marching swagger, the SA were in fact little more than an organised gang of bullies and thugs. However, they were very well organised indeed, and each man was sworn to follow the orders of Hitler and Röhm. At the same time, the Nazis gradually became more mainstream, at least in Bavaria, with Hitler being welcomed into Munich society and being courted by many prominent businessmen. (Obviously, the latter did not see themselves as the ‘capitalists’ he routinely attacked in his vitriolic speeches.) Even the great hero of the First World War, General Erich Ludendorff, allowed himself to become known as one of Hitler’s associates.

During the same period of the early 1920s, Benito Mussolini’s fascist party in Italy had gained increasing control of that nation. The Nazis eagerly mimicked the Italian fascists in policy and even styles of dress. When Mussolini rallied his followers into a grand ‘March on Rome’ to seize control of Italy, Hitler was truly inspired. He felt that the same thing could be accomplished in Germany, with the fascists taking control of Bavaria and igniting a spontaneous national revolution that would allow him to take over the central government in Berlin.

Believing that they had the support of Bavaria’s most influential politician, Gustav von Kahr, Hitler and Ludendorff conspired to make their move in November 1923. At the head of a column of his SA loyalists, Hitler burst into a large Munich beer hall where von Kahr was presiding over a large public meeting. At gunpoint, the young Führer demanded that Kahr support him, and declared that Ludendorff would command the new government that would replace the republic currently presiding in Berlin.

Not a Nazi supporter after all, Kahr threw his influence behind Hitler’s opposition as soon as he got out of there. The next day the SA marched on the Bavarian War Ministry, intending to overthrow the provincial government and begin the march on Berlin. The Nazis were met by a phalanx of well-armed police who didn’t hold their fire: sixteen party members were killed and Hitler was arrested and soon found himself being tried for high treason.

Fortunately for Hitler (and unfortunately for the rest of the world), the Nazi Führer was allowed to speak for many hours at his trial. Ever a gifted orator, he used his new national forum to rally many more disillusioned Germans to the Nazi cause. He was sentenced to five years in Landsberg Prison, where he quickly became a favourite of the guards and received a steady stream of mail from his admirers. He was pardoned by the Bavarian Supreme Court before the end of 1924, having served barely a year of his sentence, and emerged from prison far more famous and influential than he had been when he was convicted.

Furthermore, he put his time in prison to very good use, writing a book that he called Mein Kampf (‘My Struggle’). He used that forum to expound upon his racist beliefs, and to articulate his claim to Germany’s destiny as masters of Europe. A key element of that claim was his declaration that the Aryan people would need lebensraum – that is, space in which to grow and expand their population. Implicit in that claim was that the land would have to come from someone else, and already the Nazis were turning their attentions, ambitions and plans to the fertile steppes of Poland and Russia.

However, when Hitler emerged from prison conditions in Germany were better than they had been since the Great War. By 1927 industrial production was back to pre-war levels, and though unemployment was still rife, the jobless were by then being provided with compensation by the government. Things were going so well that, in national elections in 1928, the Nazis could only muster 2.5 per cent of the vote, compared to 10.5 per cent for the communists.

I remember that my father let me climb up one of his ladders when I was really little, maybe 3 years old. He had one of his tall ladders against the side of the apartment where we lived, and I started climbing up. He let me go up for a while, and then he followed me and caught up, so that by the time I was two stories up, I was right in his lap. Then he took me down again, but even then I wasn’t afraid of heights. I guess I was always supposed to be a sign maker!

Actually, it was amazing what my dad used to do. His longest ladder was 14 metres (about 44 feet)! It was made out of wood, and was very heavy. But when he had to hang a sign really high he would put up that long ladder, then drag a 6-metre (18 feet) ladder up to the top and tie that on to the 14-metre ladder. If he needed to, he would take a 4-metre (12 feet) ladder and lash it to the top of the other two. He’d put braces against the whole thing so it wouldn’t swing. Still, it seemed crazy to me!

My brother Hermann did some work with my father, but he wasn’t happy about it. I think because his own mother had died when he was so young, he never really felt that close to the rest of our family. My mom, Anna, wanted Hermann to call her ‘mother’ but he wouldn’t do it. Hermann was one to get in trouble – he stole a lot of stuff, I remember. He was so much older than me that we didn’t know each other very well, at least until after the war.

There’s a lot of water in and around Berlin, with the Rivers Havel and Spree flowing through the city; in lots of places those rivers spread out and became wide enough to be called a lake (See, in German) such as the Tegeler See, Langer See and Grosser Wannsee. There were also huge tracts of woods and forest. Some, like the Tiergarten Park in the middle of the city, had roads and paths and formal gardens, kind of like Central Park in New York. In other places, like the Grunewald Forest and the Spandau Forest, the areas were really pretty wild.

In Berlin, the communists were more popular than the fascists. Hermann belonged to a local youth sports club in the early thirties. I remember he used to go kayaking with that group. The communists ran those clubs, and they tried to let us know that the fascists were trouble. But by then the Nazis were getting stronger, even in Berlin.

Even before Hitler came to power, we could tell that it wouldn’t be too much longer before they took over the whole country. By the early thirties they were always having marches in the street, and the brownshirts would beat people up who didn’t give the Nazi salute. Everyone was afraid of them.

– Helmut Jacobitz

A World Depressed

The New York Stock Exchange crashed on 19 October 1929, and within a matter of weeks the economy of the entire world ground to a halt. The Great Depression swept across the globe with a wave of job losses, business bankruptcies, and famine, despair and hopelessness that seemed to paralyse the planet. By 1930, unemployment in Germany had reached 3 million, and it would be six million by 1932. Under the pressure of those numbers, the republic could not maintain compensation to those who were out of work. Gradually succumbing to this growing despair, the entire government collapsed.

The coalition that had more or less successfully seen Germany through the latter part of the 1920s could not sustain an alliance under the bleak shroud of the depression. Monarchists vied with democrats, while communists always challenged the right-wing fascists. With the ageing Paul von Hindenburg in the primarily symbolic post of president, new chancellor Heinrich Brüning hailed from the predominantly Catholic Centre Party, but could not gain a majority and form a government. By 1930, with no legitimate political presence taking the reins, it became the norm for Germany to be ruled by decree – an ominous stepping stone for the coming authoritarian regime.