Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Whitney Straight made his own way in life. Born in New York with a silver spoon in his mouth, he would earn his living in the boardrooms of some of Britain's greatest companies. He dropped out of Cambridge to become an outstanding racing driver and run a team of Maseratis across Europe and Africa. A qualified pilot at 17, he revolutionised aircraft design for the enthusiast, and his extraordinary efforts in the Second World War saw him rise from Pilot Officer to Air Commodore. He survived the invasion of Norway, a crash-landing in occupied France and a year as a PoW to emerge with an MC, DFC and US Legion of Merit. After the war, Straight rejected Churchill's proposal of a career in politics and instead became CEO of BOAC, transforming it into a national airline to be proud of. At Rolls-Royce, he railed against a company dominated by engineers who made poor businessmen, and played a founding role in the separate paths of the aero and auto businesses that are still seen today. An incurable romantic, he could never imagine being married to anyone other than his wife, yet he had numerous relationships. Paul Kenny has been granted unfettered access to Straight's diaries and photograph albums, and has scoured archives on both sides of the Atlantic, leaving no stone unturned in pursuit of the full story of one of the twentieth century's greatest mavericks.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 619

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Whitney and Daphne, upon their return from honeymoon, 5 September 1935. (Author’s collection)

In fond memory of the very finest of fellows, Bert Flower

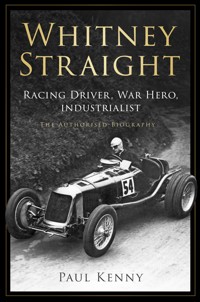

Front cover and spine illustration: Whitney breaking the three-year old record on the Shelsley Walsh hill climb, 30 September 1933 (Midland Automobile Club).

Back cover quotes: Whitney’s diary, 6 November 1942; Churchill Archive Centre, CHAR 20/200/59, Whitney Straight, letter to Winston Churchill, 5 March 1945; HSBC Archives, London, UK GCS-0101, File relating to W. Straight, Kenneth Barber, Secretary of Midland Bank, letter to Lord Alanbrooke, 5 October 1956.

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Paul Kenny, 2025

The right of Paul Kenny to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 83705 008 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

Contents

Acknowledgements

Prologue

1. New York

2. After Willard

3. Dartington

4. Cambridge or Racing?

5. A Brief, Busy Attempt at Both

6. Racing Wins Out

7. The Straight Stable

8. From Brooklands to Bremgarten

9. Facing Facts

10. Daphne

11. High Flyer

12. War

13. Captivity

14. Expanding Horizons

15. To BOAC, Via BEA

16. Breaking Up

17. Non-Exec

18. Liquidation

19. A Good Sport and Afraid of Nothing

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

My heartfelt thanks go to Whitney’s daughters, Camilla Bowater and Amanda Opinsky, and their respective husbands, Michael and Jim, for their very considerable help and support throughout this project. The willingness of Camilla and Amanda to let me read their father’s diaries and to quote extensively from them was of crucial importance, as it enabled Whitney’s observations to infuse my text. They also kindly contributed to the transcription of the diaries and to the acquisition of certain archival photographs.

Their late mother, Lady Daphne Straight, deserves special mention. After Whitney’s untimely death, she found the courage and patience to ensure his papers went to good homes – his motor racing material to Beaulieu, his logbook and wartime photo albums to the RAF Museum, his travel papers to the Royal Geographic Society and so on. She made my job as her husband’s biographer a great deal easier.

Whitney’s son, Barney Walker, was one of the first people I approached about the book, and I shall always be grateful to him and his wife Helen for the support they gave me.

Special thanks go to the woman who made a much better job than me of deciphering the appalling handwriting Whitney employed in his diaries – the queen of transcribers, Maureen Moran.

The staff at Cornell University’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, home to the archives of Whitney’s father Willard and of his mother Dorothy in respect of her New York years, were enormously helpful. My thanks and best wishes go to them, and to the team at Devon Heritage Centre, custodian of the great bulk of Dartington’s archives. I wish to pay particular tribute to the late Yvonne Widger, Archives & Collection Administrator at The Dartington Hall Trust, in whose little office behind Dartington’s cinema screen I read Whitney’s school reports and correspondence with his stepfather. Local historian Kevin Mount provided expert insight on various Dartington points.

Jeremy Vaughan, Head of Motoring at the Royal Automobile Club, kindly permitted me to use the Clubhouse library to research contemporary accounts of Whitney’s years as a racing driver, and Clubhouse Librarian Trevor Dunmore was a most helpful host. Special thanks also go to Leif Snellman, proprietor of goldenera.fi, The Golden Era of Grand Prix Racing. He has scoured contemporaneous accounts of the important Continental races of the inter-war years in British, French, German and Italian magazines to provide a balanced, objective account of those meetings. He saved me many weeks of research time. Maserati historian Adam Ferrington deserves special mention too.

The British Airways Heritage Collection houses meticulous records of BEA and BOAC. Jim Davies and Adrian Constable were expert and considerate hosts throughout my lengthy stay with them, and Adrian kindly read my aviation chapters and provided many valuable insights. I also want to credit Gavin McGuffie and Mathilde Jourdan, respectively Senior Archivist and Archives Assistant at the Postal Museum, and Helen Ceci, Archivist at HSBC History. Well-maintained corporate archives are a joy to work with.

By contrast, I acknowledge that I might have done a better job of narrating Whitney’s time at Rolls-Royce, and his Girobank work for the Post Office. Sadly, I was unable to access either the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust or Santander archives.

My two pre-readers, David Hanley and David Lowe, read each draft chapter as it came off the production line and helped me avoid numerous clunks and typos. My productivity was also helped by Rich Thomas and my son, Ben Kenny, who ensured that all three screens on my desk kept working to optimal effect.

Dr James Hansell made diagnoses from contemporary accounts, demystified medical terminology and provided valuable insight on medical matters.

Emily Clegg and Nicolai Holst of CACI went to enormous trouble to accurately map Whitney’s week on the run in occupied and Vichy France. My thanks and compliments also go to Ian Dewsbery, Louisa Keyworth and Symon Porteous of Lovell Johns for the other maps in the book, and for the assiduous way they created the plans of the Brooklands track layouts Whitney raced over.

I owe so much to my agent, Tom Cull, most notably for introducing me to The History Press. It has been a great pleasure working with The History Press, and I want to thank in particular Mark Beynon, the commissioning editor who signed me up; his successor Amy Rigg; project editor Jezz Palmer; designers Martin Latham and Anita Pumfrey; campaigns executive Graham Robson; editor Paul Middleton; proofreader James Ryan; and indexer Joanna Luke.

Others who kindly gave of their time and knowledge include Sabu Advani; Rupert Allason; Peter Amos; Beth Astridge, University Archivist, and Christine Davies, Special Collections and Archives Co-ordinator in the University of Kent’s Special Collections and Archives department; Malcolm Barber; Frank Bowles of the Department of Archives and Modern Manuscripts at Cambridge University Library; Sophie Bridges, Archivist at Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, University of Cambridge; John Brinkmann; Keila Bruggar, AHHA Intern at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress; Anna Bühler, Legal Secretary at the Public Prosecutor’s Office of the Canton of Bern; Dean Butler; Pamela Clark, former Senior Archivist at the Royal Archives and her successor, Julie Crocker; Tom Clarke; Patrick Collins, Curator, Vehicles and Research at the National Motor Museum Trust, Beaulieu; Jacqueline Cox, Keeper of Cambridge University Archives; Athena Demetriou, Bodleian Libraries’ Admissions Officer; Stephen Dorril; Svenja Duppenbecker; David Elliot; the late Bill Elmhirst; the late Mike Evans, Chairman Emeritus of the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust; Paul Fearnley; Adam Ferrington; Malcolm Fillimore; Rupert Finch Hatton; Fergus Fleming; David K. Frazier and Zach Downey of Indiana University’s Lilly Library; Bryan Gable, Special Collections, Revs Institute; Ivor Game; Jon Gilbert of the Adrian Harrington bookshop; Jennifer Govan, Senior Librarian in Research and Information Services, Gottesman Libraries of Teachers College, Columbia University; Adam Green, Senior Assistant Archivist at Trinity College Library, Cambridge; Nina Hadaway, Archive, Library and Research Manager at the RAF Museum; Mark Hawkins; Tim Healey; Glyn Hughes, Honorary Archivist of the Alpine Club; Gillian Humphreys, Library Assistant at Weston Library, Oxford; the late Chris Jacques; Wolfgang Kaese; Tomas Karlsson; Helen Keen of Surrey History Centre; Mark Knights of Beaulieu Film and Video; Howard Kroplick, Co-President of the Roslyn Landmark Society; Jane Lagesse; Beatrice Meecham, Engagement & Heritage Project Officer at Brooklands Museum; Dr Anne McLaughlin, Digitisation Services Manager, Trinity College Library, Cambridge; Robin McCullagh of the Royal Irish Automobile Club; Kim and Mitch McCullough; Gabrielle Mihaescu, former Cemetery Associate of the American Battle Monuments Commission, Suresnes American Cemetery, Paris; David Moore, Midland Automobile Club Archivist; David Morys, Archivist of the Bugatti Trust; Tom Moulson; Micah Musheno, Licensing Manager of the Whitney Museum of American Art; the late Mary Bride Nicholson; Doug Nye; Nick Opinsky; Adrian Porter and Sophia Elek; Christine Reynolds, Assistant Keeper of the Muniments, the Library, Westminster Abbey; Jonathan Rishton, former editor of The Automobile; Chris Royle; Dr Benjamin Ryser of the State Archives of the Canton of Bern; Christiane Salecker of Audi Tradition; April Sankey, Operations Director of Awards Intelligence; Erwin Schöllkopf; Martin Scröder; Mickaël Simon; Quentin Spurring; Philip Strickland; David Swig at RM Sotheby’s; Corinne Turner, former Managing Director of Ian Fleming Publications; Jan Turner, Deputy Librarian at the Royal Geographical Society; Laurent Viton; Lin Watson, Senior Archivist at Teign Heritage – Teignmouth and Shaldon Museum; Maurice Wickstead; Richard Williams; and Anne Williamson.

Last but the very opposite of least, I thank my extraordinary wife, Jane. I could not conceivably have completed this project without her love and support.

My thanks go to all of the above, and my apologies to those who helped me and whom I have not acknowledged.

Any errors or omissions are entirely mine.

Paul Kenny, TeddingtonJanuary 2025

Prologue

Cornell University’s Willard Straight Hall is one of America’s oldest purpose-built students’ union buildings. Opened in 1925, and designed by New York architects Delano & Aldrich, it makes highly effective use of the steep contours of the campus’ Libe Slope – walk the thirty paces or so from the front door to the Memorial Room, and there are now five further floors beneath you. Long banners depicting the insignia of each of the University’s fifteen colleges and schools hang from the ceiling of the Memorial Room, and an imposing stone fireplace dominates its right-hand wall.

The inscription above it reads:

Treat all women with chivalry ** The respect of your fellows is worth more than applause ** Understand and sympathise with those who are less fortunate than you are ** Make up your own mind but respect the opinions of others ** Don’t think a thing right or wrong just because someone tells you so ** Think it out yourself, guided by the advice of those whom you respect ** Hold your head high and your mind open, you can always learn ** Extracts from Willard Straight’s letter to his son

Before departing for France to join the American Expeditionary Force in December 1917, Major Willard Straight had written the letter to his elder son, and sealed it in an envelope addressed to ‘Master Whitney Straight … if anything happens to me’. Though Willard survived the First World War, he died just weeks after the Armistice, cut down by pneumonia brought on by Spanish Flu, and thus 6-year-old Whitney came to read the words that his father had hoped he never would.

This book is the story of the young American boy who read that letter, the English gentleman he became and the extent to which he heeded his father’s advice.

1

New York

Outside on the streets of New York, horseless carriages were vying for supremacy over horse-drawn buggies. Inside the five-storey townhouse on East 67th Street, near the corner with Madison Avenue, Dr Cragin’s attempts to induce the baby had failed. It was clear now that the expectant parents would not get their wish – their first child would not be born on election day. Nor would their great friend, Theodore Roosevelt, be returning to the White House. His decision to run against its current occupant, William Taft, had split the Republican vote and assured Woodrow Wilson of becoming the twenty-eighth president of the United States. An anxious night ensued, and it was not until 4.45 the following afternoon, Wednesday, 6 November 1912, that the baby arrived, weighing 7lb 14oz. He was nicknamed ‘Bill’ but at a simple service, held at home in the new year, he was christened Whitney Willard Straight. In the tradition of the time, his given names were drawn from each side of his family – Whitney was his mother Dorothy’s maiden name, and Willard the first name of his father.

Dorothy Whitney’s christening, twenty-six years earlier, had been a much grander affair. It was held in Washington’s St John’s Church, across Lafayette Square from the White House. Among the congregation of 500 sat President Grover Cleveland and his entire cabinet. Dorothy’s father, William, had been influential in Cleveland’s presidential campaign, and at the time of her birth was busy rebuilding the US fleet as secretary of the navy. When Cleveland was defeated in the 1888 election, William left politics and the family moved to New York, where he invested in railroads. Young Dorothy and her friend Gladys Vanderbilt chatted on a private telephone line rigged up between their nurseries on opposite sides of Fifth Avenue.

She was just 6 when she was told she was going on a journey, and led in to say goodbye to her mother, Flora, who lay reclining on a sofa. Only later did she learn that Flora had died while she was away. In January 1904, William was taken ill at the opera. He failed to have his appendicitis treated until too late, and died five days later of peritonitis. Dorothy, aged 17, became one of New York’s most prominent heiresses, and moved back to her childhood home on Fifth Avenue, now owned by her brother Harry. Just two years later, she established her own household at Applegreen, a large, three-storey, shingle-style house on her late father’s estate at Old Westbury, on Long Island’s North Shore. Harry had recently become vice president of Long Island Motor Parkway Inc. When the road opened in 1908, it passed south of Applegreen, and Dorothy lived in rural splendour with her companion-cum-chaperone, Beatrice Bend, daughter of the late George Bend, who had served on the governing body of the New York Stock Exchange.

Dorothy exploited her independence to the full. Away from the usual dinners, theatre visits and book clubs, she studied political economy at Columbia, left Applegreen at 5 a.m. to take her seat in the grandstand for a Vanderbilt Cup race and enjoyed a grand tour of Europe with just Beatrice and Beatrice’s mother Elizabeth for company. She was clear in what she expected from marriage. She had seen many ‘matches’ result in unsatisfactory unions, and was confident about what ultimately counted: ‘Perfect faith in each other – that above all things is the truest, surest foundation, and I can’t imagine anything more wonderful than this sort of understanding between two people. Nothing then could really go wrong.’1 Thus far, none of her suitors, whether from the New York world of politics and the professions, or among the lords and counts across the Atlantic, had come close to meeting her criteria.

In January 1909, she was invited to Washington to attend the social events marking the end of Roosevelt’s second term in office. Sitting next to her at dinner one evening was someone quite unlike the other young men she had met. His name was Willard Straight. He had been born in January 1880 in Oswego, on the New York shore of Lake Ontario. His mother, Emma Dickerman, had met Henry Straight while teaching at the Nebraska school where he was principal. Sadly, Henry contracted tuberculosis and died in 1886, and Emma suffered the same fate four years later. Aware that her condition was terminal, she arranged for Willard and his sister Hazel to be raised by friends of hers in Oswego.

Willard found the arrangement frustrating and ended up being expelled from school, but a year at a military academy in Bordentown, New Jersey, helped him adopt a more disciplined approach to life, and he went on to read Architecture at Cornell University in Ithaca, some 200 miles north-west of New York City. After graduating in 1901, he joined China’s maritime operations, helping to maintain an orderly customs function and manage commercial traffic along the coast and on the Yangtze River. He took on direct representation of America’s overseas interests in 1905, when he became a vice consul, first in Korea, and then in Cuba. There, he formed a lifelong friendship with an architect, Bill Delano, and took personal responsibility for arranging the honeymoon of Roosevelt’s daughter Alice and Nicholas Longworth, a future speaker of the House of Representatives. Alice’s father took note, and influenced Willard’s next role, supporting US trade in what was then Manchuria, as Consul-General in Mukden, modern-day Shenyang.

Now fluent in Mandarin, Willard’s engagements with China grew more commercial and, shortly after meeting Dorothy in Washington, he became the representative of a group of US banks negotiating a large international loan to China. The objective was to make the country more resilient to Russian and Japanese influence, and more receptive to trade with the West. In May 1909, while in New York for meetings with the banks, he saw Dorothy again, and she invited him out for an afternoon riding at Applegreen. She was fascinated by his work and his tales of the Orient, and he was delighted to learn that she would be visiting China on her forthcoming world tour. They agreed to meet in Beijing. Dorothy’s intrepid band of women on the tour comprised her maid, Louisa Weinstein, and Beatrice and Elizabeth Bend. They sailed from San Francisco to Japan, and when they reached Seoul, Willard took responsibility for their safe passage to Beijing. He sent two of his staff to translate and cook for them in a private railway carriage, and he and his housemate, a diplomat named Henry Fletcher, moved out to the US legation and made their home available to Dorothy and her party.

A blissful fortnight of walks, rides, dinners, late-night conversations and serenading ensued. Dorothy was swept along by it all, and when she wrote to thank Willard, it was in the most glowing of terms. ‘Oh Wise Man of the East,’ she began, and wrote of ‘two of the happiest weeks I have ever known’.2 But she bid him ‘goodbye’ more than once and, in wishing him ‘true happiness in the future, for you deserve the best there is’,3 she had no expectation that she would be part of that future. Willard, however, was in no doubt where his future lay, and four months later, when Dorothy and her party arrived in Cairo, she was greeted by thirty of his letters that made his feelings for her quite clear. While in Cairo, she met Roosevelt and his family, who had arrived from a hunting trip, and when Willard came up in conversation, she learned that the former president rated him highly. It left her hoping that Roosevelt would serve a third term, and make Willard his secretary of state. As things stood, however, Willard could hardly be considered a suitable match. When he saw her briefly, on his way to London to update banker J.P. Morgan on the state of the loan negotiations, she rejected his marriage proposal.

But Willard kept up his long-distance campaign, and his prospects brightened considerably when he returned to New York in the spring of 1911, having played a significant role in the successful conclusion of the loan negotiations with China. Now he had the status and respect to complement the trust that had shone through in his many letters. When he next proposed to her, Dorothy accepted. The engagement was only announced after the couple had sailed from New York, in the company of both Bends, and the wedding took place in Geneva, far from the prying eyes of the New York press corps.

They honeymooned in Venice, then travelled up to Paris to begin the two-week rail journey to Beijing. They arrived on 11 October, the very day on which the city of Wuhan, 700 miles to the south, fell to revolutionaries – 2,000 years of Chinese imperial rule was drawing to a violent end. An early visitor to their first marital home was a major with the local contingent of US marines, with a present of two revolvers. By the beginning of March 1912, looting and executions had become commonplace in Beijing, but Willard and Dorothy still felt safe enough to dine one evening at the nearby home of George Morrison, Chinese correspondent of The Times. Violence erupted outside, and Willard dashed back to rescue Dorothy’s maid, Louisa, and bring her to Morrison’s house. It took twenty marines to escort the group to the safety of the US legation, Dorothy in a rickshaw, with Louisa in her lap, and a few belongings tied on behind.

With the international loans signed, there clearly was little value in Willard and Dorothy continuing to live in such danger, and they set off for London in late March. Dorothy found the Trans-Siberian Railway more arduous this time. She was pregnant with Whitney, and suffering from morning sickness. England proved a welcome respite. They stayed with Dorothy’s elder sister, Pauline, and her husband, Almeric Paget, 1st Baron Queensborough. Dorothy enjoyed her time with Pauline, and followed from afar the many twists and turns in the US presidential election campaign, while Willard commuted to and from the London offices of Morgan Grenfell. It was not until August that they headed for home, and leased the East 67th Street townhouse where Whitney would be born.

On 14 October, Roosevelt was shot before he was due to speak at a rally in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. His glasses case and a folded copy of the address prevented the bullet from doing much damage, and he still gave his speech before being taken to hospital, but Dorothy rushed the following morning to New York’s Hotel Manhattan to comfort his wife, Edith. From there she visited her doctor, and after that there would be no more rushing. At her next consultation, on 28 October, he ordered her straight home to bed. Two nights later, Willard played host to their dinner guests without her, and left her at home while he led them down to Madison Square Garden to hear Roosevelt’s first speech since Milwaukee. At the end of the week, Dorothy received a visit from one of her father’s former lawyers, William Page, so that she could update her will. Given what she was about to go through, her caution was well-placed. Whitney was born fit and well after a 27-hour labour, but Dorothy was left in great pain from complications of the bladder and kidneys. Three weeks passed before she was well enough to go downstairs for dinner, and Whitney was a month old before she had her first post-natal bath. They finally left the city for Applegreen on 11 December.

Christmas was a quiet affair, notable to baby Whitney only for being put on Borden’s condensed milk. Nurse Bates was his primary carer early on, but his parents were actively involved with him from the start. Dorothy often bathed him, and Willard regularly sketched him in a special book, which sadly has not survived. By early February, Whitney was sitting on his mother’s lap, ‘laughing & cooing & talking to himself & really enjoying life. He holds his head up by himself.’4 A regular feature of family life was the weighing of ‘Bill’ each Sunday. At six months, he was up to 19lb 4oz.

The family’s first summer holiday together was spent in Manhasset, just a few miles west of Applegreen, though they took the more scenic trip around Sands Point aboard a chartered boat. Amid all the lunches, dinners, tennis and golf, Dorothy regularly strolled into the village with Whitney in his pram. She was the proudest of mothers, and found her son ‘sweet and dignified and proud of himself. People turned around to look at him wherever he went and his little serious pink face seemed to call for the smiles from passers-by.’5

Wilson’s defeat of Roosevelt not only jeopardised Willard’s political aspirations, but also meant his work on the international loans to China had been in vain. The country was still in turmoil, and the Wilson administration was opposed to dollar diplomacy. This led to a period of uncertainty for Willard. He was now an American banker with little experience of American banking. Nevertheless, while Roosevelt remained on the political sidelines, Willard and Dorothy put her wealth to effective use. They founded a new, pro-Roosevelt, magazine, The New Republic, and installed as its editor Herbert Croly, the political philosopher whose book, The Promise of America, they had read to each other while travelling.

They called in Willard’s architect friend, Bill Delano, to turn the old Cotton Exchange in Hanover Square into India House, a club for businessmen interested in foreign trade. They also employed Delano to design an impressive stable block at Applegreen, and a superb new mansion, inspired by the Wren-designed wing at Hampton Court Palace. It stands to this day at 1130 Fifth Avenue, on the corner with 94th Street. There was even a garage built in complementary style, two blocks south. ‘If I do say so,’ Delano wrote later, ‘it’s a well-planned and lovely house; once inside, it seems much larger than it really is.’6

In early July 1914, Dorothy, heavily pregnant with her second child, found Whitney, now 20 months old, upset and agitated. Within days, he was very unwell indeed with what she feared was dysentery. Doctors visited him frequently and Miss Barker, who had attended the infant Whitney while Dorothy recovered from her labour, re-joined the team as night nurse. For more than three weeks, he moved his bowels a dozen times a day and bled heavily from his rectum. To make matters worse, Willard came home from a polo match with a cracked bone in his ankle. But Dorothy had still more pressing concerns to attend to. On Sunday, 2 August, after another long labour, she gave birth to a daughter, named Beatrice after Miss Bend, but nicknamed Biddy. Across the Atlantic, the lamps were going out all over Europe. The day before Biddy’s birth, the Germans declared war on Russia. The day after it, they declared war on France. Britain entered the war the next day. Back home, Beatrice Bend left for the family cottage in Onteora in the Catskills, to prepare the way for Nurse Bates’ arrival the next day with Whitney. His mother, baby sister and entourage joined him three weeks later. By then, he was well again, but he would suffer with rectal bleeding in adulthood too.

Two years later, on 1 September 1916, Willard and Dorothy’s third child, Michael, was born. At the time, the family was holidaying in Southampton, on the South Shore of Long Island, and Whitney was enjoying his first swims in the ocean with his father, but the holiday was curtailed when a German U-boat sank several ships off Nantucket. Knowing that America’s entry into the war was only a matter of time, Willard lobbied for a role in the State Department. He wrote directly to President Wilson, and spoke also with Wilson’s adviser on Europe, the self-styled Colonel Edward House. Willard had first met House in 1915, and impressed him by being able to speak on his behalf to France’s hawkish foreign minister, Théophile Delcassé. But Willard’s politics blocked his way to a role in Wilson’s administration, and instead he sat his officers’ examination. In May 1917, a month after the US entered the war, he was commissioned a major in the Adjutant General’s reserve corps.

Willard’s last weekend before departing for France was spent with his family. He posed for photographs on the lawn at Applegreen, young Whitney standing proudly beside him in a little soldier suit, then took Dorothy and the children back into town for a service at the cathedral. He wrote a letter the next day and sealed it in an envelope addressed to ‘Master Whitney Straight … if anything happens to me’. Early on Wednesday, 12 December, he sailed for Europe, arriving in Paris on Boxing Day. He and Dorothy slipped back into the long-distance correspondence of their early days. Whitney joined in, and offered up a little prayer each night: ‘Dear God – please keep my Daddy safe tonight. Keep him safe till morning light.’7

Willard was indeed kept safe. Keen though he was to lead a battalion into action, his organisational skills were far too prized to have him exposed to danger. His first task was to implement the War Risk Insurance Bureau’s new life insurance policy for US servicemen. Within seven weeks, he and a complement of fewer than 100 men, utilising vehicles borrowed from the Red Cross and huts from the YMCA, wrote $1.25 billion of policies on the lives of a quarter of a million personnel scattered across France. It was an extraordinary achievement.

In March, Willard was sent to Langres, an old cathedral town 190 miles south-east of Paris, to study operations at the Army Staff College. The town had once been the hillside stronghold of the Gauls in their wars against the Romans, and Willard sent a charming, illustrated letter to Whitney, telling him about the legend of the Gallic chieftain, Sabinus. One sketch was of Sabinus brandishing a spear at a sanglier (wild boar): ‘It is dark brown in colour and has long bristles and little beady black eyes – and tusks … which he sometimes uses when he’s being hunted – to cut the people who are chasing him.’8 In his letters to his children, Willard was quite happy to bend the truth to suit the moral of his tale. In this case, he claimed that the deaths of Sabinus and his family had inspired the Gauls to defeat the Romans. ‘So you see that although Sabinus and Mrs Sabinus and their children didn’t live to see it – their bravery and heroism in the end saved their country. That’s what people who are fighting today are trying to do.’9

Whitney’s letters to his father were brief and to the point: ‘Dear Daddy-addy, I love you very much and want you to come back home ... Beatrice sends you a big kiss. Do make haste and come home again to your little boy Bill.’10 Willard sent him a collection of postcards from Langres, for him to share with Biddy and Michael. They showed naïve depictions of a little American boy in uniform with a little French girl. On the back of each, Willard composed a short verse, like this one:

In olden days the armoured knights

Kept vigil here, and had their fights

Between the hours of lunch and four

And then they went to eat some more11

Willard completed his course at the Army Staff College in June, and joined 3rd Corps HQ, where he took responsibility for logistics. His manual on the subject was adopted by GHQ, and he was sent back to Langres to lecture on it.

Meanwhile, Whitney’s busiest summer yet had begun with a visit to Roosevelt’s Oyster Bay home. The former president was an entertaining host and gave his young guest some hunting knives. Whitney played with the largest of them, terrifying his mother. Next came another short trip, to the Roslyn water works. Whitney was transfixed by the machinery. ‘Each engine had three big pistons’, he dictated to Dorothy to forward to Willard:

and then when the man wanted to stop it, do you know what he did? Each engine had 3 oil tanks at each side – and then the man when he wanted to stop it he turned each of these little oil taps around – and then turned two little taps off – and then he put the clutch off – and then he went to the boiler room and put the break back and forth – and then the engine stopped – and after that he turned a little wheel!12

Whitney was given a new soldier suit to replace the one he had worn for the photographs with his father, but perhaps the uniform of a US Army Air Service pilot would have been more appropriate. He had seen a triplane bomber flying on exercise, or in his own words, ‘a bomb dropping plane and it had 3 wings’,13 and he found it even more thrilling than the Roslyn water works. He and his cousin, Bobby Sandborne, collected some boxes and planks and built and painted their own biplane. They called it the Sandborne Straight and, while it may have lacked the comfort of the Miles Whitney Straight of eighteen years later, it is clear that Whitney had already become obsessed with flying.

The family returned to Southampton for their 1918 summer holiday. It suited Dorothy – being by the Atlantic made her feel closer to Willard. She told him, ‘Here by this great ocean your spirit seems actual, one with mine.’14 It suited Whitney too, for the long beach and the many children visiting it each day enabled him to conduct war games with his friends. Young Charlie Potter told his mother that, ‘Whitney Straight is a good sport and afraid of nothing’,15 while Dorothy’s friend Edith Bates considered him ‘the manliest little boy she has ever seen’.16 He grew stronger and braver as a swimmer, troubling Dorothy when he swam far out into the water. He was maturing too – one morning on the beach, he asked his mother if he could buy some sweets and charge them to her. ‘That’s a new game,’17 she thought.

A brutal reminder of the hazards facing those serving in Europe came when news reached New York of the death of Roosevelt’s youngest son, Quentin, shot down near the village of Chamery, south-east of Reims, on 14 July, Bastille Day. He had been due to marry Dorothy’s niece, Flora. ‘He died game – dear boy,’ wrote Willard, ‘but it’s a bad business, this airman’s game.’18 A month later, while on leave in Normandy, Willard sent his children another of his illustrated parables. This one explained how the Vikings in their long boats had behaved like pirates before colonising the north of France, and becoming first Normans, then kings of England. ‘You must understand all these things, so that you can see how wonderful it is that French and English and Americans are all together fighting the Germans who are just like the pirates of the old days.’19

In October, Willard was sent to the château in Senlis, 35 miles north of Paris, which served as the headquarters of Marshal Ferdinand Foch, Supreme Allied Commander. Here, he reported to Colonel Thomas Mott, the liaison officer between Foch and the Commander of the American Expeditionary Force, General John ‘Black Jack’ Pershing. At the very centre of communications recording the final stages of the war, Willard wrote again to ‘my dear Bill’ on his 6th birthday:

You are going to have fights. I hope you will. Never fight a boy smaller than you are. Never let a bigger boy bully a little fellow. That’s the sort of thing we have been fighting for in France. Remember too that as you grow older you’ll think more and fight less with your fists; but you must always fight with all your heart and all your ability for the same thing that you fight for, when you are a boy, with your fists ... Just remember this on your birthday, always. For as Beatrice was born on the day that war commenced, so the war comes to an end, really, on your birthday; and if this war is to be worth the great sacrifices that it has cost, you and I and all of us must try to be worthy of the men who have died so that we might live, and we must live in the same fine spirit that has enabled them to make the supreme sacrifice. Just remember that.20

Four days later, Mott drove to Paris with the text of the Armistice, leaving Willard at the château in Senlis. His task was to advise Allied HQ when it had been signed, or record any changes in the text and pass these on to Mott. As he sat in the library, waiting into the early hours, he resumed the letter to Dorothy he had begun a week earlier. ‘I love you everything’, he wrote, using the line he and Dorothy shared with young Whitney. In the last half inch of space, at the bottom of eight pages of tiny, spidery writing, he added this: ‘5.40 AM Nov 11th. General Destiches has telephoned that hostilities will cease on Nov. 11 – at 11 AM … It is Peace – Best Beloved – think what it means!’21 Thus did Major Willard Straight of the American Expeditionary Force record the end of the First World War, and his part in it.

As to what peace meant, he was clear about the role America must play in the forthcoming negotiations. He thought it critical that Britain and France did not extract too high a price from Germany, but he was not confident that Wilson was up to the job. ‘It will be a catfight,’ he wrote to Dorothy:

WW is not a leader – not for a moment – he’s no more ready for peace than he was for war … We should have made our bargain with the Allies when we first came in – or at least when we began to send troops in such large numbers. Now we will be apt to get nothing – not even the peace we fight for, but a peace which will instead of being founded on a League of Nations, have the foundation for other wars.22

Colonel House arrived in Paris to lead the US peace delegation. Dorothy had hosted House and his wife at Applegreen several times, and also visited their New York apartment, pressing upon him how valuable Willard could be to the negotiations. Her efforts paid off, and when Willard returned to Paris and checked into the Hotel de Crillon, House added him to his team. Having seen at first hand the persuasiveness of Dorothy across the dinner table, House also proposed that she should come to Paris. Willard decided Whitney should come too, to have memories of such a historic moment.

On the evening of 17 November Willard added a few last lines to the letter to Dorothy he had started only hours after finishing the previous one in the library in Senlis. ‘Dear Beloved – are you coming – that’s all I’m thinking of.’ He concluded, ‘And now bed – I love you everything – Yours Willard.’23 The last words he ever wrote fell, slanting down the page. The man who had maintained an even hand through thousands of words to his family over the previous eleven months was deeply exhausted.

He rose from his bed the next morning, but returned to it later in the day with a fever. He had contracted Spanish Flu, the contagion that would claim more lives than the war itself. Colonel House also went down with it, but rallied soon enough, while Willard’s condition worsened. As the week wore on, his temperature rose ever higher, and pneumonia was diagnosed. Delirium set in, and his breathing grew increasingly laboured. He died at 1 a.m. on Sunday, 1 December, aged just 38. His only contribution to the preparations for the peace talks he was so keen to influence was to tell President Clemenceau and General Pershing when Wilson would arrive in Paris. There would indeed be another war. When the Armistice was formally agreed, in a carriage of Marshall Foch’s train in the Forest of Compiègne, Foch pointedly walked out as the Germans signed it. Adolf Hitler would have the same carriage drawn to the same forest glade twenty-two years later, and walk out as the French signed their surrender.

Incidentally, Dorothy’s most recent biographer has queried why the 60-year-old Colonel House recovered swiftly from his encounter with Spanish Flu while the much younger Willard succumbed to it. She asks if, after the abandonment of Roosevelt’s political aspirations, Wilson’s cancellation of the international loans to China and the denial of any opportunity to become a war hero, ‘poor Willard died of shame?’24 That is to misunderstand both Spanish Flu and Willard. The US Centers (sic) for Disease Control and Prevention notes of Spanish Flu, ‘Mortality was high in people younger than 5 years old, 20–40 years old, and 65 years and older. The high mortality in healthy people, including those in the 20–40 year age group, was a unique feature of this pandemic.’25 As for Willard, the Versailles peace talks were about to give this most international of Americans the chance to make a real difference on the world stage, and provide the platform from which to mount a career in politics or diplomacy. Shame was the last thing on his mind.

Back in New York, the 6-year-old boy who should have been enjoying his first Thanksgiving recess from school was instead handed the letter his father had written almost a year earlier. It read:

My dear Bill

You may never see this letter. I hope you never will. But should anything happen to me, I want you to have a word – you as the oldest – that you may have it for yourself and your blithe young sister and your brother Michael. My father died when I was seven years old, and I had no word save such as my mother gave me. She was taken, too, before I knew what she meant. I trust for your sake, and the sake of all three of you, your mother will be there to guide you. All the best in you comes from her, and the finest in you will be brought out by her. You are blessed as no other children have been blessed in your mother. May your worship for her – for it will be with you as it is with me, reverence and real worship – guide you and lead you to treat all women with real chivalry. Save yourself and tell Michael to save himself, that you may go clean and unashamed to her who will be your wife and the mother some day of your children. Many good men don’t. They may laugh at you, but they will respect you, and the respect of your fellows is worth more than their applause. Sometimes you’ll get both.

You are a fine honest lad. Be honest. Be honest and frank and generous even if others tell you you are quixotic. It is better to be quixotic than the opposite. Here again be like your mother.

Be gentle and strong. Defend those who are weak. Understand and sympathise with those who are less fortunate than you are. But do not let those who try to do so mistake your gentleness for weakness. Fight if you must and if you must, fight hard and fight fair.

Make up your own mind, but respect the opinion of others. Don’t think a thing right or wrong because someone tells you so. Think it out yourself guided by the advice of those whom you respect.

Watch your mother; help her; comfort her. Don’t let her tire herself out. Watch over your sister; protect her.

Hold your head high, and keep your mind open. You can always learn. God bless you.

Your Father.26

2

After Willard

SS Leviathan was due to sail from Brest on 8 December, carrying the first tranche of US troops to leave France, and Colonel House made arrangements for the ship to take Willard home too. But Dorothy would not hear of it – she wanted him buried among the fallen compatriots whom he had so admired. So it was that, on 3 December, a Cadillac bore Willard’s flag-draped coffin away from the Hotel de Crillon and up to the American Military Cemetery being laid out to the west of Paris in Suresnes. Uniformed soldiers slow-marched on each side of it, and friends and associates followed behind on foot. The address was given by Bishop Charles Brent, senior chaplain to the US Forces: ‘His organising genius was exactly what the moment needed. We had thought of him as one of those destined and prepared to make a valuable contribution to the reconstruction of life in the new era that is at its dawn. But it had been ordered otherwise …’1

Cables and letters of condolence rained in on Applegreen. Among them was a letter to Whitney, postmarked 11 December, yet clearly written by his father some time earlier. Willard had sent ‘My Dear Jonny Soldier-Man’2 some postcards of Napoleon’s tomb at Les Invalides in Paris. Since 1915, the French had displayed captured German aircraft and artillery there, and Willard told his son, ‘Some day when the war is over I’ll bring you to see all these things yourself. Be a good boy and look after Mother and Beatrice & Michael.’3 Many of Willard’s letters to his son had ended like this, exhorting him to be a brave man and look after the family while he was away. Whitney was just 6, the only one of the children who really remembered their father, and all he could do was to bottle up his own emotions and try not to be too much of a nuisance to his grieving mother. On New Year’s Day 1919, a month after Willard’s death, even Louisa, Dorothy’s maid, could see that Whitney ‘felt real bad’.4

A sombre mood hung over the house. Willard’s possessions arrived home over Christmas, and no one could summon the will to even inform Dorothy. He may have been away for a year, but the family had spent so much time writing to him and discussing his letters to them that he had remained a central presence in their lives. The abrupt end to this correspondence created a vacuum that made their sense of loss all the sharper. The entire household fell ill. The contagion may have been called Spanish Flu, but it was in the process of wiping a dozen years off US life expectancy, and the family and staff were lucky to survive their bouts with it. Sorrow mounted on sorrow when Theodore Roosevelt died of a pulmonary embolism on 6 January, aged just 60.

Returning to school after a grief-stricken Christmas was a welcome distraction for Whitney. He had joined first grade at The Lincoln School on Park Avenue just months earlier. The Lincoln was managed by Columbia University’s Teachers College, but it had been created by the General Education Board, a philanthropic organisation focused on innovative education, and established and funded by oil magnate John D. Rockefeller. The creative friction between Teachers College and the GEB over just how innovative The Lincoln could be was a recurring feature of the relationship, and something that Dorothy observed from a unique position. Utterly passionate about education, she sat on The Lincoln’s Administrative Board, and on the Executive Committee and Committee on Education at Teachers College, where she was also a trustee.

The Rockefeller connection and the school’s location, a block from where Whitney had been born, might have led to an exclusive student population, but that would have gone against GEB principles, and a generous range of scholarships ensured that an eclectic cross-section of the city’s young boys and girls attended. As the New York Times’ Elmer Davis discovered, ‘The children of a number of multi-millionaire households are balanced by the children of coachmen and butlers, and of mechanics and store-keepers, just as the children of old New York families are balanced by children whose parents brought them over in the steerage not very long ago.’5

This mixed environment led young Whitney to question the whole concept of wealth, and his right to it. He announced one year that he wanted no birthday presents at all, and Dorothy told him she was proud ‘to have a son who was a rebel’.6 She credited The Lincoln with developing his independence of thought. ‘In that atmosphere he can’t be content to be just a rich boy. The influence is all the other way.’7

Whitney thrived under the ‘units of work’ approach practised in The Lincoln’s Elementary School. One early focus was on milk – the children considered its importance to diet, and drank and cooked with it; they visited a dairy farm and a pasteurisation plant; they learned how milk was transported into the city, and how it was marketed and sold there; they maintained records of how much milk was consumed at home; and they purchased milk for the classroom, paying for it from the school bank.

The Lincoln closed for the summer recess of 1919 in mid-June, and Dorothy took her children away for their first holiday without their father. Southampton, with its memories of Whitney’s swimming lessons with his father, and of Dorothy’s almost telepathic connection across the ocean to Willard in France, was out of the question. They headed north almost 300 miles, to Raquette Lake in the Adirondacks. Here, Whitney was taught the rudiments of sailing, and how to fish for trout and bass. He spent large portions of each day with his mother, who felt sufficiently recovered to pick up her diary for the first time as a widow. Her entries during her time at Raquette Lake are littered with phrases like ‘too heavenly’8 and ‘most perfect day’.9 Apart from the time Whitney almost lost his fingers in a mishap with an axe, the family was enjoying a wonderful, restorative holiday together.

Yet a week later, Dorothy was making plans to sail for France with her niece Flora, having received a cable from General Pershing inviting her to Paris. The children would stay in the company of a few household staff to enjoy the mountain life, but their mother sailed from New York on 14 August. It is not clear if she understood the true purpose of Pershing’s invitation. Many contemplative vigils at Willard’s grave, and ‘a most wonderful and happy day’10 in Langres visiting his old house, the Staff College and the Cathedral, clearly helped her in her grieving. She also supported Flora through the trip to Quentin’s grave near Chamery. But the bulk of her time in France was spent in the company of politicians, officers and architects, agreeing to help fund the completion of a military cemetery fit for heroes at Suresnes.

Dorothy had always had a strongly philanthropic nature, and she became particularly keen to pursue it in memory of Willard. She was now sole proprietor of The New Republic, she had commitments to numerous educational establishments and she raised funds for causes like the Women’s Trade Union League. It all meant that she saw less of her children, and lost sight of how they were coping with their own grief. Throughout his young life, Whitney had grown used to spending more time with governesses and tutors than with his parents, but with Willard dead, he felt Dorothy’s absences more keenly. She did not return from France until the last weekend of September. There was just time to take the children to the nearby Mineola Fair on the Saturday. Then, on the Monday, Whitney returned to school.

Dorothy may have seen less of her elder son than he would have wished, but a most unlikely source demonstrates that she had some understanding of his nature, if not his feelings. The love she and Willard had shared for each other had been so spiritual that she was genuinely surprised not to be able to feel his guiding hand from beyond the grave, and in her isolation she turned to a Maryland spiritualist known only as Mary K. The woman filled more than a dozen notebooks in large, looping handwriting, purporting to be Willard’s answers to Dorothy’s questions. Given that these can only have come inadvertently from Dorothy talking to Mary K about her family, the observations concerning Whitney are most revealing. When asked what the future had in store for him, the answer recorded in one of the notebooks was, ‘He will have a life of great worldly interest. He will mix in the world – stand out but more as a good businessman and good fellow – a companion – he will be restless and fond of pleasure as well as work.’11 And when asked how Whitney should be prepared for such a life, the answer proved just as prescient: ‘He will not be a literary type – he will be more of a sports and businessman, so fit him for that.’12

On 19 April 1920, 8-year-old Whitney looked neither sporty nor business-like at New York’s first big social occasion since the war. The great and the good of New York society thronged into St Bartholomew’s Church on Park Avenue to see Flora marry stockbroker Roderick Tower, an old friend of Quentin’s from their pilot-training days. Whitney was the only page boy, bedecked in frilly shirt, white gloves and satin trousers, and carrying a larger posy than any of the flower girls.

He was much more in his element come July, when the family first visited the house that was to be their base for the next five summers – a clifftop idyll in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, overlooking Buzzards Bay. The waters there are protected from the Atlantic by Cape Cod, but the currents ripping between the Elizabeth Islands can make for treacherous conditions – the ideal environment for young Whitney to work on his sailing skills. There was also a summer camp for him to enjoy, run by the nearby Oceanographic Institute. This was just as well, for Dorothy spent much of the holiday sorting through Willard’s papers and meeting with Herbert Croly of The New Republic. He was going to write Willard’s biography, and Dorothy would be closely involved.

When Whitney returned to The Lincoln at the end of summer, he found to his delight that his passion for boats and the water made him the ideal pupil for his third-grade teacher, Nell Curtis. The curriculum she had chosen was based on her love of the Hudson River, and she led the twenty boys and girls in her charge through its piers, boatyards and docks, and taught them about the vessels plying the river and how they were built. In class, she used a reflectoscope, an early form of projector, to show the children artists’ impressions of the Hudson a century and two centuries earlier. She took them to libraries and galleries to learn about ancient Egypt, and the millennia of traffic on the Nile, and oversaw their creation of a frieze that ran round the classroom, charting the development of the boat.

A pattern emerged in Whitney’s life. Dorothy absorbed herself with her causes and committees, and based the family in the city each semester, Applegreen at the weekends and at Christmas, and Woods Hole for the summer. Biddy joined The Lincoln, then Michael. ‘Never let a bigger boy bully a little fellow’,13 Whitney’s father had taught him, and now he put the advice into practice – older boys waiting for Michael found Whitney waiting for them.

At Applegreen, he loved taking his brother and sister for a ride around the lawn in his Studebaker – not a car, but a goat-drawn carriage. Another vehicle he was fond of was the Marmon convertible Dorothy bought for his tutor, Albert Crystal. Whitney persuaded him to take the children out on to the Long Island Motor Parkway, leaving them gasping for breath at a joyous 60mph. Crystal also fed Whitney’s love of aviation, taking him regularly on the short drive from Applegreen to Roosevelt Field. The airfield had been used for training purposes during the war, and was renamed in honour of Quentin in 1919. In 1927, Charles Lindbergh would take off from there in his Spirit of St Louis, on the first successful transatlantic solo flight, but for Whitney and Michael, Roosevelt Field was the place where they could marvel at the pilots giving acrobatic joyrides for a dollar. The hangars surrounding the field were full of Curtis JN-4 ‘Jenny’ biplanes, now surplus to military requirements and the prized possessions of young men taking up flying as a pastime. Crystal would lift Whitney up into a cockpit so he could wiggle the control stick, stretch down to operate the rudder, and dream of being an aviator. ‘For Mr Crystal and me,’ recalled Michael many years later, ‘those hours were a diversion. For Whitney they were a life unfolding.’14

On Saturday, 2 July 1921, while most of the country was fixated on the million-dollar prize fight between Jack Dempsey and Georges Carpentier, all seemed normal at Applegreen. The Lincoln had broken up for the summer, the children were looking forward to returning to Woods Hole, and Dorothy had another round of guests to entertain. What was unusual was that one of them agreed to Whitney’s invitation to participate in an apple fight, then led Dorothy and the children on a bird’s nest expedition. The following morning, the man followed Whitney down to the poultry shed and patiently explained to the 10-year-old why a bird could grow so much when part of its body was removed. He pointed out how the combs and spurs on a cockerel distinguished it from a pullet. Whitney wanted to know why the cockerels were to be put into the breeding pens, and the man was just explaining why this would ensure the eggs would hatch when Whitney’s governess, Mme Colas, arrived and the conversation came to a halt. By the time Whitney and the man had burned their fingers on the Fourth of July fireworks they set off the next evening, Whitney had made a friend, if not for life, then at least for some considerable time.

Leonard Knight Elmhirst, or Jerry as the family would come to know him, was born in June 1893, and raised in the village of Laxton, in Yorkshire, England. He graduated with an MA in history from Trinity College Cambridge, and worked briefly for a missionary in India. In advance of being demobbed from the British army in 1919, he took a course in agriculture, and decided to study the subject in more depth in the US. A shipping strike in England meant he arrived late at Willard’s old university, Cornell, but within a day he had arranged a tuition grant, a course in agricultural science, and accommodation at a club for overseas students called the Cosmopolitan. There, he ate for free and received an extra pumpkin pie a week in return for working in the kitchens early each morning. The other club members so respected Jerry’s determination that in his second semester they elected him president, a role that brought with it an onerous responsibility. The Cosmopolitan owed creditors $80,000, and its insolvency would cause acute embarrassment for the Cornell lecturers keeping it afloat with promissory notes. As president, it fell to Jerry to avoid this at all costs, and he was advised there was only one person in the country who could help him – Dorothy.

In preparing assiduously for his audience with her, he learned that Willard had himself tried to help the Cosmopolitan during his undergraduate days, and had left provision in his will for anything that would make Cornell ‘a more human place’.15