Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: The Prime Ministers

- Sprache: Englisch

'An excellent summation of the life and times of Winston Churchill' Andrew Roberts 'Caddick-Adams understands the two world wars, and his subject's role in them, superbly' Simon Heffer, New Statesman 'A witty and enjoyable political biography of Winston Churchill ... Brilliantly done' The Past In Winston Churchill, veteran historian Peter Caddick-Adams gives us an overview of Churchill's life, from his early days as a soldier and part-time journalist through to the Second World War and beyond. Caddick-Adams argues that the recipe for Churchill's success during his wartime premiership of 1940-45 can be found in the First World War. The nation, and its leaders, had undergone a 'dress rehearsal' in 1914-18: conscription, rationing, convoys, air raids, mass production, women's uniformed services, coalitions and war cabinets had all happened before, and Churchill had been there when they did. This experience, combined with Churchill's extraordinary abilities (along with some foibles), were what enabled Britain to survive. READER REVIEWS - 'A fantastic brief biography of Churchill, incredibly well written, researched and presented' - 'An excellent introduction to Churchill's life' - 'Caddick-Adams presents a rich and insightful portrait of one of history's most iconic figures, making this a must-read for anyone interested in Churchill's legacy' - 'Nimbly covers the extent of his remarkable life, providing marvellous detail'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 268

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Peter Caddick-Adams

By God They Can Fight! A History of the 143rd Infantry BrigadeThe Fight for Iraq January–June 2003Monty and Rommel: Parallel LivesMonte Cassino: Ten Armies in HellSnow and Steel: Battle of the Bulge 1944–45Sand and Steel: A New History of D-Day1945: Victory in the WestThe Little Book of Warfare

ToSimon Baynes MPTim Loughton MPLord (Andrew) RobertsSir Desmond Swayne MPCelebrating over forty years of personal and political friendship

Contents

Foreword by Tim Loughton MPIntroductionPart I 1 · Frontiers and Wars 2 · Gathering Storm 3 · World Crisis 4 · Roving Commissions 5 · While England Slept Part II 6 · Twilight War 7 · Into Battle 8 · Finest Hour 9 · Blood, Sweat and Tears 10 · Unrelenting Struggle 11 · Onwards to Victory 12 · Liberation 13 · Sinews of Peace Further Reading and AcknowledgementsNotesForeword

Over twenty-seven years ago I entered the chamber of the House of Commons for the first time as a Member of Parliament. Full of elan and no doubt misguided confidence, I joined a small coterie of Conservative MPs who had survived the trenches against the Blair onslaught of May 1997 to sit on the subsequently heavily depopulated Opposition benches.

But the Commons is a great leveller. There will always be someone with more confidence than you and, more to the point, many someones with every reason to be. Thus it was, I am sure, a twenty-five-year-old Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill strode an identical route to park himself on the green benches after the 1900 general election more boldly than this thirty-four-year-old ninety-seven years later. This was, after all, the genesis of a political career which promised much and of which much was expected. As the Church Family Newspaper put it: ‘Such a man as Winston Churchill must climb very high up the ladder of life. The world wants such men. They make history, they influence men’s minds, they carry conviction.’

The layout of the chamber Churchill occupied has changed little, although it was completely rebuilt after the Luftwaffe rained terror on the Palace of Westminster, culminating in the firestorm of 10 May 1941. It is largely down to the force of nature which was Churchill himself. In October 1943 the then Prime Minister moved a motion which proposed setting up a select committee of the House to report on the rebuilding of the chamber and the damaged sections of the Commons. He was adamant it should be ‘restored in all essentials to its old form, convenience and dignity’. After all, he contended: ‘We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us.’

He insisted the shape continue to be oblong rather than semicircular, distrustful of the semicircular assembly, ‘which appeals to political theorists, enables every individual or every group to move round the centre, adopting various shades of pink according as the weather changes’. Perhaps with more than a hint of conceit, let alone melodrama, he railed against logic, which, having

created in so many countries semicircular assemblies which have buildings which give to every Member not only a seat to sit in but often a desk to write at, with a lid to bang, has proved fatal to Parliamentary Government as we know it here in its home and in the land of its birth.

Thus Churchill impressed upon the select committee, yet to be formed, a second condition: the chamber should be small and intimate, with no prospect of sufficient seating allocated to every member. He warned: ‘If the House is big enough to contain all its members, nine-tenths of its debates will be conducted in the depressing atmosphere of an almost empty or half-empty Chamber. The essence of good House of Commons speaking is the conversational style, the facility for quick, informal interruptions and interchanges.’

Unsurprisingly, Churchill got his way. A select committee was formed under the Father of the House, Lord Winterton, who also held the distinction of once having been the ‘Baby of the House’, having been first elected at the age of twenty-one, even younger than Churchill. The select committee reported in January 1945. Churchill’s ‘brief’ about size and shape was respected, and the new plan designed by architect Giles Gilbert Scott provided for 427 seats (give or take, depending on the size of respective members’ posterior dimensions on the long benches) for the then 640 elected members. Clearance of the site began in May 1945, and the new chamber was officially opened in the presence of King George VI, on 26 October 1950.

As if the rebuilding being in the image so advocated by Churchill was not enough, colleagues were left in no doubt about the huge impression he made on the place when the arch connecting the Members’ Lobby with the chamber became known as the ‘Churchill Arch’. The original had been built by Sir Charles Barry following the rebuilding after the catastrophic fire of 1834. Churchill suggested the archway be rebuilt from the original damaged stonework, symbolising continuity, but also preserved as a ‘Monument to the Ordeal’ which the Palace of Westminster had been subjected to during the Blitz.

One thing the new boy Churchill was not confronted with when first taking his seat in 1900 was the larger-than-life bronze statue of himself designed by Oscar Nemon. It was placed on the vacant pedestal on the left-hand side of the arch in 1969, four years after the great man’s death. Less still would he have been intimidated by the even larger bronze statue of Margaret Thatcher installed thirty-eight years later and which occupies the other side of the Members’ Lobby. Both appear to dominate the rather less ostentatious bronzes of Lloyd George and Attlee, which complete the pedestal quartet in the lobby.

There is a tradition that former Prime Ministers do not qualify for a full-size statue until after their deaths. However, I remember well being in attendance for the unveiling of the Thatcher pointy bronze by sculptor Antony Dufort in February 2007, six years before her death. Standing behind the great lady herself, I heard her declare: ‘I might have preferred iron, but bronze will do. It won’t rust.’

Today there is a sign at the base of the Churchill statue exhorting visitors to refrain from touching. The reason – toe damage. Visitors, along with a few members, have traditionally rubbed the foot of their favourite statue on entering the chamber, for good luck. Such was his popularity that on more than one occasion the protruding left foot of the great man has had to be restored.

So, any new member coming into the House of Commons chamber cannot escape the huge influence Churchill has had on our workplace. Though it may now be almost sixty years after his death, you walk through his arch, under his gaze, and then you battle to secure one of the reduced number of seats on the benches in the intimate adversarial-style chamber he advocated. And if that isn’t enough, being pointed at by Mrs Thatcher on your way is a further reminder that you walk in the footsteps of parliamentary giants.

What on earth could you possibly say or do to match that? In his briefly interrupted parliamentary career between his maiden speech on 18 February 1901 and his retirement as an MP on 27 July 1964, over nine years after stepping down as Prime Minister, Churchill has no fewer than 29,232 entries recorded in Hansard, the Parliamentary record. This includes, of course, the famous, epoch-defining ‘blood, toil, tears and sweat’ and ‘Democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms which have been tried from time to time’, masterpieces from the Dispatch Box. His lethally witty one-liners are difficult to equal. Take the description of his Labour opponent Clem Attlee as ‘a modest man who has a good deal to be modest about’.

There are few places in the Palace of Westminster where Churchill doesn’t feature. The Churchill Room, with its rather smaller but no less impressive bust overlooking diners, is one of the smarter function rooms, while in Westminster Hall his name is etched in brass for posterity. The inscription marks the spot where Churchill’s coffin lay in state for three days, with over 320,000 members of the public filing past to pay their respects. As Edward Bacon in the Illustrated London News described them, they had the ‘mesmeric effect of a river flowing past’.

Churchill was one of only three Prime Ministers accorded the honour of a state funeral, the others being Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, and the Liberal veteran William Ewart Gladstone. While Wellington lay in state at the Royal Military Hospital, Chelsea, Gladstone and Churchill took centre stage in the huge Westminster Hall built by the son of the Conqueror, William II, and completed in 1097. It is a magnificent hall, at its genesis the largest building in Europe, and has survived the great fire of 1834, IRA bombs and the Blitz. From there Churchill’s body was taken aboard a gun carriage to a state funeral at St Paul’s Cathedral.

Westminster Hall is literally a place full of great history. By day it is bustling with visitors and staff going about their business as the main entry point to the Palace of Westminster. But by night, as I often take a detour after working late, when it is usually completely deserted, you really get a sense of the great figures of history who occupied the space in centuries past, dead and alive. Other than for Churchill and Gladstone, brass plaques also mark the locations of the catafalques where the late Queen lay in state, along with her parents and grandparents.

Recorded too is the spot where King Charles I was tried for treason and subsequently condemned to beheading in 1649. The same fate befell Henry VIII’s Lord High Chancellor Thomas More in 1535, while the first governor general of Bengal, Warren Hastings, is one of the few to have stood trial in Westminster Hall and kept his head. I often take groups of visiting parliamentarians from around the world on tours of the Palace of Westminster, starting in Westminster Hall. Despite my best efforts to bring the great history of our workplace to life, waxing lyrical about the relevance of the Civil War, which led to a republic following the King’s execution, or the break with Rome because of Henry VIII’s libido, it is invariably the stop at the Churchill plaque which garners the most interest and name recognition.

His spirit is with us in the bars too. George Bernard Shaw’s verdict on Parliament is also perhaps most fitting for Churchill himself: ‘Alcohol is a very necessary article… It enables Parliament to do things at eleven at night that no sane person would do at eleven in the morning.’ Hear, hear to that!

And, of course, well beyond Westminster, Churchill the politician is never far away. I remember being part of a parliamentary delegation to Iran in less turbulent times. We were entertained by the British ambassador at the imposing British residency in Tehran. There we were given dinner in the formal dining room, overlooked by a photograph of Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin in the very same places where we sat, with little having changed about the decor. The original visitors’ book attests to the occasion. The event was of course part of the historic Tehran Conference of November 1943, the first time the three leaders had met together, and at which they began to plot the closing stages of the Second World War.

Winston Churchill dominated British politics for much of the middle part of the twentieth century, but his reputation survives intact with later generations, as witnessed by his winning the popular vote as the Greatest Briton a few years ago. His domination may have extended on the world stage well beyond the British Isles, but as we are reminded every time we step into the Palace of Westminster, there was his natural stage. Those who come after cannot but be infected by the character he injected so forcefully into it. Proudly declaring himself a ‘child of the House of Commons’, he left behind a very proud mother.

Tim Loughton MP

Tower of the Koutoubia Mosque

Introduction

As a painting it is perfectly proportioned. In the centre lie the walls of Marrakech, their depth emphasised by left-sloping diagonal shadows, cast by the setting sun. The foreground is busy with tiny figures around the main gate, while the background is framed by the Atlas Mountains, whose snowy peaks reflect the Moroccan glare. The Tower of the Koutoubia Mosque – the picture’s title – looms over the city; it is the hour when the muezzin is calling the faithful to prayer. Consisting mainly of whites, pinks and ochres, the image is a happy, confident one, conveying warmth with a sense of travel and exotic adventure. This portrait of Marrakech sums up its maker.

Expertly painted on 25 January 1943, the canvas speaks of antiquity and ritual, of far-off lands, emphasised by palm trees in the middle distance. Although he completed over 500 pictures, this was the only one made by Winston Churchill during the entire Second World War. In fact, the composition illustrates a refuge: a rare moment when we glimpse the war leader free from stress. It was also one of his best, and in 1948 he gifted it to President Truman with a note: ‘This picture… is about as presentable as anything I can produce. It shows the beautiful panorama of the snow-capped Atlas Mountains in Marrakech. This is the view I persuaded your predecessor [Roosevelt] to see before he left North Africa after the Casablanca Conference.’

In addition to submitting canvases to the Royal Academy of Arts under the pseudonym David Winter – which resulted in his election as an Honorary Academician Extraordinary in 1948 – our subject was twice Prime Minister, holding the office for a total of eight years and 240 days. Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (1874–1965) has merited more biographies than all his predecessors and successors put together. It is tempting to see his career through many different lenses, for his achievements during a ninety-year lifetime spanning six monarchs encompassed so much more than politics, including painting.

The only British premier to take part in a cavalry charge under fire, he was also the first to possess an atomic weapon. Besides being known as an animal breeder, aristocrat, aviator, beekeeper, big-game hunter, bon viveur, bricklayer, broadcaster, connoisseur of fine wines and tobacco (apart from Pol Roger 1928 champagne, his preferred tipple was a Martini consisting of a glass of Plymouth gin and ice, ‘supplemented with a nod toward France’), essayist, gambler, global traveller, horseman, journalist, landscape gardener, lepidopterist, monarchist, newspaper editor, Nobel Prize-winner, novelist, orchid-collector, parliamentarian, polo player, prison escapee, rose-grower, sailor, soldier, speechmaker, statesman, war correspondent, war hero, warlord and wit, one of his many lives was that of writer–historian.

Most of his long life revolved around words and his use of them. Hansard recorded 29,232 contributions made by Churchill in the Commons; he penned one novel and thirty non-fiction books, and published twenty-seven volumes of speeches in his lifetime, in addition to thousands of newspaper dispatches, book chapters and magazine articles. Historically, much understanding of his time is framed around the words he wrote about himself. ‘Not only did Mr Churchill both get his war and run it: he also got in the first account of it,’ was the verdict of one writer, which might be the wish of many successive public figures. Acknowledging his rhetorical powers, which set him apart from all other twentieth-century politicians, his patronymic has gravitated into the English language: ‘Churchillian’ resonates far beyond adherence to a set of policies, which is the narrow lot of most adjectival political surnames.

‘I have frequently been made to eat my words. I have always found them a most nourishing diet,’ Churchill once quipped at a dinner party; and, to paraphrase another Churchillian observation: ‘History will be kind to me for I intend to write it.’ ‘Churchill lived by phrase-making,’ according to biographer Roy Jenkins, and certainly much understanding of his time is derived from the words he wrote about himself. Yet ‘Winston’ and ‘Churchill’ are the words of a conjuror, immediately conveying a romance, a spell, as well as wonder at one man achieving so much. It is an enduring magic, and difficult to penetrate. In 2002, by way of example, he was ranked first in a BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons – among many similar accolades. A less well-known survey of modern British politicians and historians conducted by MORI and the University of Leeds in November 2004 placed Attlee above Churchill as the twentieth century’s most successful Prime Minister in legislative terms – but he was still in second place of the twenty-one from Salisbury to Blair.

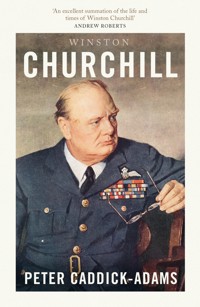

As much a global figure as a British politician, Churchill was one of the first international media celebrities. Something of a lifelong dandy, with his many uniforms (he was both an honorary colonel and an honorary air commodore) and hats, watch chains and walking canes, silk dressing gowns and siren suits, spotted bow ties and ever-present cigars, he was a man of props, which boosted his familiarity to people in the pre-television age. The cover of this book well illustrates the point. Winston never gave a television interview, but in 1954 he arranged a secret screen test with the BBC at Downing Street to evaluate the new communications medium (which he dismissed as a ‘tuppenny-ha’penny Punch and Judy show’) for himself. On viewing the grainy black-and-white footage, he decided it was not for him and ordered the film be destroyed. Though the screen test was recently rediscovered, it is through the medium of newsreels, wireless and his printed words that we associate his life.

The Churchill image has featured on postage stamps and coinage, with warships, tanks, locomotives, several schools, a Cambridge college, champagne, whisky, cocktails and cigars named after him. Blessed with intelligence, wit and wisdom, he was mostly self-educated, not having attended a university. (In later years he would sit as chancellor or rector of three universities and be awarded one honorary professorship and eleven honorary degrees.) Born in the era of boots and saddles, among Prime Ministers he was unique in being recommended for a Victoria Cross in his youth, and in old age in advocating the use of weapons of mass destruction. ‘I want you to think very seriously over this question of poison gas,’ he ordered his chiefs of staff on 6 July 1944, during the stalling Normandy campaign.

To retain a vestige of objectivity when faced with the Winston Spencer Churchill spell, modern scholarship is now concluding that his relationship with the historical truth was not always as objective as he himself would have us believe. David Cannadine has emphasised how aspects of Churchill’s flawed decision-making and prejudices during the Second World War were played down or excluded from his account of the same name. Consider: in his six-volume account of the First World War, the Eastern Front gets a whole volume to itself, while in his Second World War, of equal length, the Germano-Russian war features hardly at all. New biographers have highlighted the importance of his many secretaries, personal aides and experts: it is not generally realised Churchill’s major histories were written by teams of literary assistants and only polished by the putative author, who nevertheless minutely directed each enterprise. Author Sonia Purnell is one of the few to have highlighted the role of his strong-willed wife, Clementine ‘Clemmie’ Hozier (1885–1977), whom Winston married in 1908, but is referred to surprisingly little in his own works. Her rock solid but not uncritical support for him, particularly during the ‘Wilderness Years’ of the interwar period, her presiding over Chartwell, their country house in Kent, for forty years, and her prompts for him to show humility during the era of his triumph, shaped his character and policies, and shored him up during moments of depression.

We have John and Celia Lee to thank for reappraising the role of Winston’s brother Jack (1880–1947), younger by six years, who was also airbrushed out of history, usually by Churchill himself. An engaging and honourable man who served in the South African Light Horse with his sibling, as a stockbroker he shielded his brother from the worst effects of the 1929 Wall Street Crash and lived in Downing Street during the war after being bombed out of his own home. The self-destructive behaviour of Winston’s only son, Randolph (1911–68), also had a bearing on his father, who spoiled him. Churchill never referred to this, but during the 1930s, Randolph’s affairs with the bottle and women, as well as his efforts to enter Parliament, caused rifts between his parents.

In the war years, Randolph’s domestic disagreements with his parents grew so violent Clemmie thought her husband might suffer a seizure. Their son’s erratic service with special forces behind enemy lines in Yugoslavia merely added to the Prime Minister’s stress. Randolph would die in 1968, three years after his father, at the age of fifty-seven. Drink had turned him into a wreck, but Josh Ireland reminds us redemption of a kind was offered when, in 1960, Winston asked his heir to write his biography. During 1941, cast adrift and close to divorce, Randolph’s first wife Pamela Digby (1920–97) conducted an affair with Averell Harriman, Roosevelt’s special envoy to Europe, then coordinating the Lend-Lease programme. Although this led to the breakdown of her marriage, according to Sonia Purnell (also a Digby biographer), her Harriman ‘alliance’ probably aided Britain’s war effort significantly more than did the younger Churchill, and she supported Clementine as an energetic hostess at many important Prime Ministerial gatherings. Paradoxically, his daughter-in-law Pamela (who did eventually, after the death of her second husband in 1971, marry Averell Harriman) is considered far more important to the Winston Churchill story than his own son, Randolph.

The three surviving Churchill daughters (a fourth, Marigold, 1918–21, died aged two of septicaemia) also played important, supportive roles in his premiership, albeit ones which were minimised by their father, and left important memoirs. In the war years, each put on a different uniform of the women’s forces, helping to project the Churchill ‘brand’. The eldest, Diana (1909–63), served in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS, known as the Wrens). Sarah (1914–82) worked in photo intelligence for the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), accompanied her father to the Tehran and Yalta conferences and was romantically linked to the American ambassador, John Winant. Mary (1922–2014) joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), commanded anti-aircraft batteries and travelled to Potsdam as her father’s ADC. Although Winston and the formidable Clemmie enjoyed fifty-seven happy years together, their four children clocked up eight marriages between them. Winston’s own personality swamped those of his family: they accepted he must come first – and ‘second and third’, in Clemmie’s words – as he was so frequently away from home, ‘either fighting wars or fighting elections’, as Mary later observed. Thus, Churchill’s wartime premiership was strongly underpinned by his extended family, though writers tend to be bedazzled by the man alone.

Modern Churchill scholarship, consisting of well over a thousand volumes, is an unrelenting tsunami, much of it still amounting to excessive hagiography, though now complemented by a growing school of iconoclasm which criticises Winston not only for his imperial attitudes, and for what he did or omitted to do, but also for what he claimed he had done in his books. The plenitude of primary sources makes his life as mammoth an undertaking for the historian as the two world wars with which he was intimately involved. To further confuse the enthusiast, there have also been to date sixty-three television and film portrayals of Winston Churchill, from cameos to full-on biopics, featuring fine actors from Albert Finney, Robert Hardy and Michael Gambon to Gary Oldman, Timothy Spall and Simon Ward. A good starting point for further study is the International Churchill Society, founded in 1968. It holds conferences, hosts podcasts, and publishes the quarterly Finest Hour magazine and a monthly e-newsletter, the Chartwell Bulletin.

In this volume on his premiership, you will find I have dwelled at length on Winston’s earlier life, for the hinterland to 1940 explains how he acquired the personal tools to deliver a wartime Prime Ministership so effectively during 1940–45. He himself felt drawn not just to politics, but to the highest tier of governance, and often recorded a sense of destiny guiding his actions. Churchill truly believed he was destined for greatness, to the extent he saved everything he wrote. As a writer and biographer of his ancestor John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, and of Lord Randolph, his father, he was only too aware of the shortcomings of many libraries of personal documents, haphazardly collected like random archaeological sherds after the subject’s death. Accordingly, he started his own. Many of the speeches, personal letters, newspaper reports and state papers cited here are the result of Winston’s archiving of his own life, right down to household bills and receipts. These have ended up in the Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge, established in 1973, which has also collected many other relevant papers, including those of Admiral Jackie Fisher, Brendan Bracken and Clement Attlee, and most have now been digitised. His life was recorded in print by his official biographers, son Randolph and, after his death, the academic Sir Martin Gilbert (1936–2015), in their immense, 3,111,090-word, eight-volume work, allegedly the longest in history, published between 1966 and 1988.

Accompanying it are the twenty-three exhaustive Companion Volumes, consisting of documents and papers, variously edited by Randolph Churchill, Gilbert and latterly the American scholar Larry Arnn, which appeared over the course of fifty years, from 1967 to 2019.1 As the historian Lord (Andrew) Roberts reminds us, few other lives have ever been so minutely and comprehensively recorded through paperwork, which is one reason why so many volumes on Churchill have been penned. If you want to know about Winston’s cigars, relationship with God or alcohol, culinary tastes, war records, London tailor’s bills or plans for painting holidays, then there will be documentation leading you to the appropriate subject, always accompanied by a sense the great man is looking down, nodding his head in approval.

Part I

Frustrated by the mobility of its Boer opponents in 1900, Britain raised a number of volunteer cavalry detachments. War correspondent Winston cabled back to London, ‘More irregular corps are wanted. Are the gentlemen of England all fox-hunting?’ He went on to serve in one of them, the South African Light Horse, under Colonel Julian ‘Bungo’ Byng, future field marshal and governor general of Canada. Here, Churchill wears a khaki tunic of his own design, bearing the single ‘pip’ of a second lieutenant, three medal ribbons, his Sam Browne (cross strap) over the wrong shoulder – and an impossibly rakish slouch hat, bearing Sakabulu tail feathers with the SALH clover-leaf badge on its left side.

Chapter 1

Frontiers and Wars

Churchill’s parents influenced him in different ways. His mother was Jennie Jerome (1854–1921), daughter of a wealthy New York businessman and noted beauty, who had been introduced to her future husband by no less than the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) at Cowes Week in 1873. The pair were engaged three days later and wed at the British embassy in Paris on 15 April 1874. Winston was born at the end of the same year and John (Jack) in 1880. She was distant to her two sons during their childhoods in a not untypically Victorian way.

Her earliest letter to Winston’s father, written in 1873, announced: ‘I should like you to be as ambitious as you are clever… and I am sure you would accomplish great things.’ After his early death, she switched her not inconsiderable powers of persuasion and allure to her elder son. Jennie married twice more after Randolph’s passing, in 1900 and 1918, but remained devoted to the careers of her two boys. Winston later referred to his mother as his most ‘ardent ally’, acknowledging they ‘worked together on equal terms, more like brother and sister, than mother and son’, noting after her death she had ‘left no wire unpulled, no stone unturned, no cutlet uncooked’.

Her strong-willed attributes were inherited by Winston, but the thread running through his life was the meteoric parliamentary career of his father, Lord Randolph Churchill (1849–95), whose twin-volume biographer he became in 1906. The second surviving son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, whose appellation of ‘Lord’ was a courtesy title, Randolph had entered the House of Commons in 1874, in his mid-twenties, and quickly established himself as one of the leading figures in the Conservative Party, becoming both Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House aged thirty-seven. Most colleagues felt he was destined to lead the country, but within months he had fallen out with his Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, and, in a fit of hubris, resigned from the Cabinet. Lord Randolph’s political career was effectively over, though he remained an MP until his premature death.

In Winston’s mind was not the tragedy of Lord Randolph’s resignation letter of 1886, but of his passing nine years later, aged only forty-five. Obvious to Winston were his father’s alienating mood swings, symptoms of vertigo, palpitations, mental decline and general inarticulation, and it was soon apparent a creeping illness was slowly robbing him of his persuasive powers in a very public fashion. This was later understood to be syphilis, a contemporary diagnosis believed by – among others – Winston Churchill all his life. As Lord Randolph’s friend the future Prime Minister Lord Rosebery wrote: ‘The progress of the disease was slow at first, but its signs were obvious, and when it began his career was closed… There was no curtain, no retirement, he died by inches in public.’ While former Prime Minister and Churchill biographer Boris Johnson asserted Lord Randolph died ‘in political isolation and syphilitic despair’, modern medical analysis suggests a left-side brain tumour may more closely correspond to his known symptoms, a diagnosis supported by a host of biographers, including Robert Rhodes James and Richard Holmes.

The effects of this were threefold. First, Churchill was convinced he, too, might die young. He therefore became ‘a young man in a hurry’, determined to achieve as much as possible in the brief span he believed had been allotted to him. He also played up to this sense of impatience by stressing his premature birth, having been born to the seven-and-a-half-months-pregnant Lady Randolph on 30 November 1874. Second, believing his father to have been possessed of a sexually transmitted disease persuaded him to remain chaste to his wife, ‘my darling Clemmie’. He never strayed and, indeed, they had a remarkably close marriage for fifty-seven years. Finally, Churchill – who lionised his father – felt Lord Randolph had been cut off in his prime, before he could go on to achieve greater things. Accordingly, the highest offices and a parliamentary career were expectations for the son, who lost his father when aged just twenty.

Winston later claimed he had had only ‘three or four long intimate conversations’ with his father, and spoke of his mother as shining for him ‘like the Evening Star. I loved her dearly – but at a distance,’ words which perhaps refer to Lord Randolph as well. The young Churchill thus had a very unusual start in life, inspired by both parents in different ways. Even had he wished it otherwise, history owned him from birth: he was born at Blenheim Palace, his Marlborough ancestor’s mansion. Once described by the historian Simon Schama as a ‘swaggering baroque pile,’ the early eighteenth-century Blenheim is an important place to visit to understand the man.