5,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Fitzcarraldo Editions

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

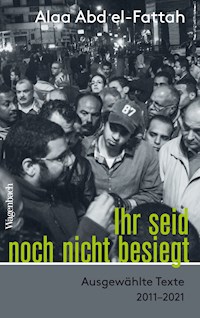

Alaa Abd el-Fattah is arguably the most high-profile political prisoner in Egypt, if not the Arab world, rising to international prominence during the revolution of 2011. A fiercely independent thinker who fuses politics and technology in powerful prose, an activist whose ideas represent a global generation which has only known struggle against a failing system, a public intellectual with the rare courage to offer personal, painful honesty, Alaa's written voice came to symbolize much of what was fresh, inspiring and revolutionary about the uprisings that have defined the last decade. Collected here for the first time in English are a selection of his essays, social media posts and interviews from 2011 until the present. He has spent the majority of those years in prison, where many of these pieces were written. Together, they present not only a unique account from the frontline of a decade of global upheaval, but a catalogue of ideas about other futures those upheavals could yet reveal. From theories on technology and history to profound reflections on the meaning of prison, You Have Not Yet Been Defeated is a book about the importance of ideas, whatever their cost.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

‘Don’t read this book to be comforted. Read it to be challenged, terrified, enlightened, moved, and amazed.’

— Kamila Shamsie, author of Home Fire

‘Alaa is the bravest, most critical, most engaged citizen of us all. At a time when Egypt has been turned into a large prison, Alaa has managed to cling to his humanity and be the freest Egyptian.’

— Khaled Fahmy, author of All The Pasha’s Men

‘Alaa is in prison not because he committed a crime, not because he said too much, but because his very existence poses a threat to the state. Those who are bold, those who do not relent, will always threaten the terrified and ultimately weak state which must, to survive, squash its opponents like flies. But Alaa will not allow himself to be crushed like that, I know.’

— Jillian C. York, director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation

‘Alaa is a philosopher of everyday life and lifelong struggle; he doesn’t merely find meaning in that which we go through, especially in dark political moments, but creates meaning and gives it form in writing. And he does so from a highly entrenched and implicated place in the present. His thoughts know no frontiers; they pierce through local contexts to inspire new modes of thinking about the chaotic substance of politics.’

— Lina Attalah, editor in chief of Mada Masr

YOU HAVE NOT YET BEEN DEFEATED

SELECTED WORKS 2011–2021

ALAA ABD EL-FATTAH

Translated by A COLLECTIVE

CONTENTS

CHRONOLOGY: EGYPT 1952–2021

23 July 1952: Mid-ranking army officers stage a coup, depose King Farouq and take control of the state. Mohammed Naguib is their figurehead and the Revolution Command Council is established as the ruling authority.

August 1952: Workers’ protest for better conditions in Kafr al-Dawwar is brutally repressed, and two of the workers are sentenced to death and executed.

September 1952 – January 1953: The Agrarian Reform Law initiates a major land redistribution programme, bolsters popular support for the revolution. The Constitution of 1923 is abrogated. All political parties are dissolved and banned.

January 1954: After a short honeymoon period with the revolution, the Muslim Brotherhood is outlawed.

March 1954: Naguib, who favoured a return to constitutional government, is sidelined. Gamal Abdal Nasser consolidates power.

October 1954: Nasser survives an assassination attempt. The Brotherhood are blamed and a brutal crackdown begins.

March 1956: A new election law grants women the right to vote.

July 1956: Egypt nationalizes the Suez Canal.16

October 1956: Israel invades Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, under agreement with France and the UK, but international pressure forces their withdrawal. A major political victory for Nasser. Control of the canal is cemented.

1959: Arrests of communist intellectuals and activists begin. Hundreds are detained, some are tortured, at least two are killed, most are not released until 1964.

January 1960: Construction begins on the Aswan High Dam, Nasser’s landmark development project.

September 1961: Nasser – with Nehru of India and Tito of Yugoslavia – initiates the International Non-Aligned Movement.

June 1967: War between Israel and Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. Israel occupies the Palestinian West Bank, the Gaza strip, the Syrian Golan Heights, and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. A humiliating defeat. A war of attrition begins against Israeli forces now occupying the east bank of the Suez Canal.

September 1970: Nasser dies of a heart attack. His successor is Vice-President Anwar El-Sadat.

May 1971: Sadat purges powerful opponents with the ‘Corrective Revolution’, announces the closure of political detention centres, and starts releasing detained activists, mainly Muslim Brotherhood members.

January 1972: A student uprising demanding democracy, press freedom and a popular war to liberate Sinai, occupies Tahrir Square and is expelled by police with force.17

October 1973: Egypt and Syria launch war against Israel in an effort to regain lands lost in 1967.

April 1974: Members of an Islamist group break into the Technical Military Academy in Cairo: the first step in a planned coup to announce the birth of an Islamic State. Security forces engage, killing eleven.

April 1974: Sadat’s October Paper sets the stage for a complete reversal of economic policy: promoting entrepreneurship over central planning, and the dismantling of the public sector.

January 1977: A price hike of basic commodities triggers massive riots across the country. The army is deployed, a curfew imposed and more than 100 people are killed.

August 1978: Sadat establishes the National Democratic Party (NDP) which inherits the assets, resources and status of the state political party, the Socialist Union.

1977–79: Sadat visits Jerusalem to address the Knesset. He signs the Camp David Accords with Jimmy Carter and Menachem Begin. In response, Egypt is boycotted by most Arab countries, the headquarters of the Arab League are moved from Cairo to Tunis and Egypt’s membership is suspended.

1979: Soviet forces invade Afghanistan, triggering a guerrilla war with local Islamist mujahideen. The CIA begins covert operations in support, which Sadat is heavily involved with: supplying Soviet weapons to the fighters, training insurgents, and allowing Egyptian militant Islamists to travel to Afghanistan to join the war.18

May 1980: Sadat openly denounces the Coptic Church, accusing it of trying to establish a state within a state.

September 1981: Sadat deposes the Coptic Pope. He orders the arrests of 1,536 people – who fall across the entire political and professional spectrum. This is accompanied by asset freezes, professional expulsions and the closure of certain newspapers.

October 1981: Sadat is assassinated by members of a militant Islamist group while attending a military parade. The group begins a simultaneous insurrection in Asyut and takes control of the city for a few days before paratroopers from Cairo restore government control. Sadat is succeeded by his Vice-President Hosni Mubarak and a state of national emergency is declared. It will be continually renewed throughout the coming thirty years of Mubarak’s rule.

September 1984: Workers demonstrate and stage a sit-in at Kafr el-Dawwar Spinning & Weaving Factory (public sector), protesting rising food prices and demanding increased pay. The sit-in is violently broken up by police forces, leaving three workers dead. Several more strikes will follow, protesting rising prices, low pay, corruption, neglect of the public sector and the complicity of the official workers’ unions.

November 1987: The Arab boycott of Egypt ends, Egyptian membership of the Arab League will be restored, and its headquarters return to Cairo.

August 1989: Workers occupying the Iron & Steel Factory in Helwan are attacked by Central Security 19Forces. One worker is killed, tens are wounded, and about 600 are arrested and tortured at police stations.

February 1990: Islamist militants attack a bus carrying Israeli tourists in Egypt, killing eleven. Eight months later, they assassinate Rifaat el-Mahgoub, Speaker of Parliament, in Cairo.

January 1991: Egypt sends 35,000 troops to join the US-led war on Iraq. As a reward, $14bn of Egypt’s $46bn foreign debt is dropped.

May 1991: Egypt agrees its first structural adjustment loan with the International Monetary Fund: $380m, conditional on the removal of price controls, reduced subsidies, introduction of sales tax and an accelerated privatization programme for state-owned enterprises.

1993: Several militant Islamist attacks on tourists, senior police officials shot dead in daylight ambushes, and failed assassination attempts on the Interior Minister and the Prime Minister.

October 1994: 15,000 workers in Kafr el-Dawwar strike and occupy the factory. Security forces lay siege, cut off water and electricity. In the eventual dispersal, violence spreads across the town, injuring sixty and killing four.

June 1995: Mubarak survives an assassination attempt in Addis Ababa by a militant Islamist group from Sudan.

September 1995: Egypt becomes the first country to cooperate with the CIA’s extraordinary rendition programme. Abu Talal al-Qasimi is illegally captured by 20the CIA in Croatia and taken to Egypt. He will later be executed in Egypt.

1994–1997: Islamist attacks continue to escalate: Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz is stabbed in the neck, a bomb attack on the Egyptian embassy in Islamabad kills seventeen, tourists are attacked and killed in separate attacks at the Pyramids, the Egyptian Museum and in Luxor.

February 2000: Gamal Mubarak, Hosni Mubarak’s son, is appointed member of the ruling National Democratic Party’s general secretariat.

September 2000: The second Palestinian Intifada erupts. In Egypt, it triggers widespread demonstrations supporting the Palestinians, denouncing Mubarak’s position, and demanding a reversal of Egypt’s normalization with Israel.

September 2001: After 9/11 Egyptian intelligence acquires a new importance to the US in light of their long experience with Islamist groups. The CIA’s ‘extraordinary rendition’ programme is expanded and Egypt becomes a principal collaborator in the reception and torture of suspects.

March 2003: The US invasion of Iraq triggers large demonstrations protesting Egypt’s subservience to US foreign policy – as well as rising prices, corruption and economic policies. Tens of thousands of protestors occupy Tahrir Square for a few hours before being violently dispersed by police. 21

October 2004: Three coordinated bombs are detonated in tourist spots around Taba, South Sinai, killing 38 people.

December 2004: The first demonstration by the Kefaya (‘Enough’) movement against Mubarak, rejecting the extension of his presidency and the grooming of Gamal Mubarak to succeed him. ‘No Succession’ will become a regular anti-Mubarak slogan from now on, and Kefaya demonstrations will steadily gain traction.

July 2005: Three bombs in Sharm el-Sheikh kill 88 people, mostly Egyptians.

September 2005: Mubarak’s presidency is renewed for a fifth term. The constitution had been amended to allow multiple presidential candidates to compete in elections, though with very restrictive conditions for candidacy. Mubarak wins 88 per cent of the vote. Two months later, despite rampant violations, the Muslim Brotherhood win 20 per cent of seats in parliamentary elections.

March 2006: Around 1,000 judges stage a silent protest demanding the full independence of the judiciary. Alaa is arrested from a protest in solidarity with the judges and spends forty-five days in prison.

June 2007: In January of the previous year elections were held in the West Bank and Gaza from which Hamas emerged the victor. Fatah did not cede power which resulted in a split in the Palestinian leadership. Now, Hamas officially take control of Gaza, Israel imposes a blockade, and Egypt supports it by closing its border crossing at Rafah. 22

April 2008: Landmark strike in the massive textile factories in al-Mahalla receives support from a wide spectrum of popular organizations and groups: workers’ unions, political movements and parties, student unions, and academics. Clashes with security forces escalate and spread through the city. A group of human rights centres, NGOs, and independent lawyers team up to form The Front for the Defence of 6 April Demonstrators. The 6 April Youth Movement, a grassroots activists group, is also formed.

December 2008: Israel launches an air and ground war against the Gaza strip triggering large demonstrations in Egypt denouncing Mubarak for his friendly policies towards Israel, and demanding the permanent opening of the Rafah border crossing.

September 2009: A coalition of Egyptian human rights organizations issue a report stating that after eighteen years of ruling under Emergency Law ‘Egypt has been turned into a police state.’

June 2010: Khaled Said, 28, is dragged from a cybercafé near his home in Alexandria by two plainclothes policemen and beaten to death. The police report claims he suffocated as he tried to swallow a bag of hashish he was caught with, but Said’s family manage to take a photograph of his corpse in the morgue. His face is battered beyond recognition. They release the photograph online, along with a claim that he was killed for having video material implicating policemen in a drug deal. A new Facebook page, ‘We are all Khaled Said’, attracts hundreds of thousands of followers in a few days, becoming Egypt’s largest dissident group online.23

December 2010: ‘We are all Khaled Said’ calls for a protest on 25 January, a national holiday: Police Day. Inspired by the recent Tunisian revolution and encouraged by comments posted on the page, the admins change the event title to ‘A revolution against torture, unemployment, corruption, and injustice’.

25 January 2011: On Police Day, demonstrations erupt in several Egyptian cities and towns. Security forces respond violently, killing at least one protester in Suez.

27 January 2011: In anticipation of planned protests the following day, the Mubarak regime orders the internet be shut down.

28 January 2011: Tens of thousands of demonstrators across the country march towards the centres of their cities after Friday prayers. In the ensuing battles with the police, at least 800 people are killed and 99 police stations are burned to the ground. By sunset, the revolutionists have won - and occupied Egypt’s main city centres. The police retreat to desert barracks and the military deploy, taking up positions around key buildings. Protestors lead chants of ‘The People, the Army, One Hand’ but it is not clear what the military’s stance is.

29 January 2011: Mubarak dismisses the cabinet of Ahmad Nazif, and directs Ahmad Shafiq, Minister of Civil Aviation, to form a new cabinet. For the first time in his thirty years in power he appoints a Vice-President, Omar Suleiman, the Intelligence chief well known in Washington for his cooperation with the CIA’s rendition programme. 24

31 January 2011: In a further bid to appease protestors, Minister of the Interior, Habib El-Adly, is dismissed.

1 February 2011: Mubarak announces that he will not run for reelection at the end of his term in September 2011.

2 February 2011: The Battle of the Camel: several thousand Mubarak supporters – some paid – attack Tahrir. First with horses and a camel, then with rocks, and ultimately with live rounds from the tops of surrounding buildings. The Brotherhood now appear with full organizational force in defence of Tahrir. The battle lasts until the morning, the square holds.

11 February 2011: After eighteen days of protest that have paralyzed the country and fixed the world’s attention on Tahrir Square, Mubarak steps down and tasks the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) with running the country.

13 February 2011: SCAF suspends the constitution and dissolves Parliament.

18 February 2011: Habib El-Adly and other NDP figures are arrested by order of the Public Prosecutor.

5 March 2011: Hundreds storm the buildings of the feared State Security agency in several cities, including the headquarters in Cairo, after word spreads that papers, case files and evidence of torture was being destroyed inside.

19 March 2011: National referendum on constitutional amendments. A ‘yes’ vote – promoted by the 25Brotherhood – would mandate holding parliamentary elections before drafting a new constitution. First major rift between Islamist and revolutionary groups. ‘Yes’ takes 77 per cent of the vote.

13 April 2011: Mubarak and his sons, Alaa and Gamal, are arrested by order of the Public Prosecutor.

4 May 2011: A Palestinian reconciliation agreement brokered by Egypt is signed by Hamas and Fatah in Cairo. The interim government’s successful mediation indicates that Egypt no longer adheres to Mubarak’s policy of isolating Hamas. The Rafah border will soon be re-opened.

5 May 2011: Habib el-Adly is sentenced to twelve years in prison for financial corruption, the first Mubarak-era official to be convicted and sentenced.

3 August 2011: Mubarak’s trial, for corruption and complicity in the killing of some 900 protesters, begins and is aired live on television. Mubarak is wheeled into court on a hospital bed.

9 October 2011: The Maspero massacre. Thousands of Coptic Christians gather in Cairo to protest the burning of a church in Upper Egypt and the state’s failure to protect Copts. The army attacks, killing 26 and injuring 350.

20 October 2011: Alaa publishes ‘To Be with the Martyrs, for that is Far Better’ in national broadsheet, al-Shorouk.26

30 October 2011: Alaa is arrested by the Military Prosecutor.

19–24 November 2011: The Battle of Mohammed Mahmoud Street. A sit-in held by families of the injured of the revolution in Tahrir is attacked by police. Thousands flock to the square and engage in a five-day battle that leaves sixty dead and several thousand injured. The Muslim Brotherhood are absent, concerned the unrest could disrupt upcoming elections.

24 November 2011: SCAF announces the appointment of Mubarak-era figure, Kamal El-Ganzouri, as Prime Minister. Some protestors split from Tahrir and begin an occupation of the street outside the Cabinet Building.

28 November 2011: Parliamentary elections begin.

16–20 December 2011: The army violently disperses the sit-in at the Cabinet Building, sparking four days of clashes that leave 17 dead and some 2000 injured.

25 December 2011: After an extended hunger strike by his mother, Laila Soueif, Alaa and all the accused in the Maspero case are released by a civil judge.

21 January 2012: Parliamentary elections announced, with the Brotherhood winning 47 per cent of the seats and the Salafists, 25 per cent.

1 February 2012: The Port Said Massacre. 74 fans of Cairo football club al-Ahly, whose ultras are known as revolutionaries, are killed in al-Masry SC’s stadium. 27

31 March 2012: Breaking an earlier pledge, the Muslim Brotherhood announces Khairat el-Shater – de facto leader of the organization and a known hardliner – will run in the upcoming presidential election, with Mohammed Morsi as a reserve candidate.

14 April 2012: The Supreme Presidential Election Commission disqualifies ten presidential candidates, including el-Shater and Omar Suleiman.

2 June 2012: Mubarak and Habib el-Adly are sentenced to life in prison for ordering the killing of protesters.

24 June 2012: Mohammed Morsi is declared winner of the presidential election, with 51.7 per cent of the vote. Ahmad Shafiq – the establishment’s candidate –immediately leaves the country for the United Arab Emirates.

12 August 2012: Morsi replaces Minister of Defence Hussein Tantawi with General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, and removes Army Chief of Staff, Sami Anan.

22 November 2012: Morsi makes a unilateral power grab, declaring his decisions immune from judicial review and precluding the courts from dissolving a new Constituent Panel. Massive protests ensue.

15–22 December 2012: The new constitution hastily drafted by Islamists amid protests is approved by referendum with 63.8 per cent of the vote, but a turnout of 32.9 per cent. 28

June 2013: As Morsi’s first anniversary in power approaches, attention turns to calls for protests on 30 June. Discontent in almost all quarters is high: reforms have ceased altogether, police violence continues unabated, sectarian attacks are on the rise, promised cooperation with the revolutionary groups that helped win the election has not materialized, and the country is ravaged by increasingly frequent electricity cuts due to mismanagement of fuel supplies. A new campaign by the name of Tamarrod (‘Rebellion’) claims to have gathered millions of signatures calling for Morsi’s resignation and early elections.

30 June 2013: Millions take to the streets demanding Morsi’s departure. Counter demonstrations are organized by Morsi supporters, developing into two sit-ins in Rabaa and el-Nahda Squares in Cairo.

3 July 2013: Defence Minister General el-Sisi removes Morsi from power and installs Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court, Adly Mansour, as interim president.

24 July 2013: Sisi calls for people to take to the streets to give him a ‘mandate’ to deal with ‘terrorism’: the Brotherhood. Tens of thousands oblige.

14 August 2013: Police attack the sit-ins at Rabaa and el-Nahda squares. More than 900 people are killed. At least 42 churches are attacked in response by Islamist mobs around the country. A roundup of Brotherhood leaders and supporters begins; opposition television channels are shut down or forced into exile.29

4 November 2013: Morsi appears for the first time since his removal, on trial charged with inciting violence, the first of several court cases against him. Some charges carry the death penalty.

26 November 2013: A protest is held outside the Shura Council protesting the re-activation of a British-era law outlawing protest. It is attacked by police, who make dozens of arrests.

28 November 2013: Alaa is arrested and charged – among other things – with organizing the protest at the Shura Council. Protest is now effectively outlawed and those arrested at, or in the vicinity of, protests are handed lengthy prison sentences.

25 December 2013: The Muslim Brotherhood is officially designated a terrorist organization.

29 December 2013: Three al-Jazeera English journalists are arrested from the Marriot Hotel in Cairo on terrorism charges. The al-Jazeera channels, owned by Qatar, are aligned with the Brotherhood.

28 May 2014: Sisi wins presidential election with 96.9 per cent of the vote.

30 November 2014: In a retrial, Mubarak’s case is dismissed and Habib el-Adly acquitted over the killing of protestors in 2011.

21 April 2015: Morsi is sentenced to twenty years for charges relating to the killing of protesters in 2012.30

9 May 2015: Mubarak and his sons are sentenced to three years on corruption charges.

29 June 2015: A bomb kills the Prosecutor General, Hisham Barakat, as he leaves home on his way to work.

25 January 2016: Italian academic Giulio Regeni is killed in police custody under torture. He had been researching contemporary labour issues.

15 April 2016: Thousands demonstrate against Egypt’s transfer of the two Red Sea islands, Tiran and Sanafir, to Saudi Arabia, in the largest protests since Sisi’s election.

11 November 2016: Egypt devalues its currency, the most drastic among several liberalization measures required to secure a $12bn loan from the IMF.

2017: Egypt becomes the world’s third highest importer of weapons. Foreign debt rises to 103 per cent of GDP.

24 March 2017: Mubarak is released from prison.

6 September 2017: Human Rights Watch estimates some 60,000 political prisoners now held in Egypt and that ‘widespread and systematic torture by the security forces probably amounts to a crime against humanity’.

January 2018: Presidential elections for Sisi’s second term. All potential opponents are arrested or pull out.

30 March 2019: Alaa is released from prison, but sentenced to spend every night in his local police station, Doqqi, for the next five years. 31

17 June 2019: Mohammad Morsi collapses during a court session and dies. All national newspapers report the story with the same news bulletin of forty-three words on page three.

20 September 2019: Small street protests erupt, the first in years, triggered by a building contractor revealing shocking details about government corruption. A massive sweep of activists begins.

29 September 2019: Alaa is arrested from inside Doqqi police station.

FOREWORD

The text you are holding is living history. Many of these words were first written with pencil and paper in a cell in Egypt’s notorious Torah Prison, and smuggled out in ways we likely will never understand. One was drafted in collaboration with another political prisoner, the two men shouting ideas to each other across the dark ward. A few texts were written in relative freedom, on the eve of repeated imprisonments, or during probationary release, in an isolation cell at a police station where the author was required to spend his nights.

At every stage, and whichever form they take – essay, letter, interview, tweet, speech – they exist only because of extraordinary risks taken by the writer, intellectual, technologist and Egyptian revolutionary Alaa Abd el-Fattah. Those risks include the ever-present threat that Alaa would face further ludicrous charges, and prolonged detention. In the case of texts written during stints on the outside, or during probation, the threat – made explicit in night-time visits from state security officers – was that these writings would lead directly to his re-imprisonment, or worse. And still, he wrote.

The fact that these words are before us now, in book form, many for the first time in translation, is a result of further risks, these ones taken by friends, family, and comrades in Egypt’s luminous but brutally extinguished revolution. The ones who camped outside the prison to demand communication with the prisoner; who smuggled out hidden slips of paper; who selected the texts from Alaa’s huge body of work; who edited, translated, and contextualized them in these pages.

This careful work has taken place against the backdrop of continuous and escalating state repression against the 34regime’s political opponents. That opposition is politically and ideologically diverse. Alaa and his comrades are part of the left, internationalist, anti-sectarian, youth-led movement that is part of a global confrontation with transnational capital and its national organs, a movement that has seen expressions from Tahrir Square to Occupy Wall Street. And because this strain has refused to fully surrender its hopes for a liberated Egypt, it too has faced the wrath of the vengeful regime of General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.

As I write, Alaa is re-imprisoned, as he feared he would be, and the silence from his cell is harrowing. His sister, Sanaa Seif, a prominent organizer in her own right, is also in jail, most recently for ‘spreading false news’. His editors at Mada Masr, where many of Alaa’s writings first appeared, have also faced harassment and detention for their commitment to independent thought in a sea of state propaganda.

Alaa, as you will read, is a student of the South African freedom struggle, and in particular the Freedom Charter – a document that laid out a roadmap for collective freedom written under one of the most repressive periods of Apartheid rule; a document whose meaning and import were magnified by the raw difficulty of bringing the text into being. This text is also a product of revolutionary effort, of subterfuge and hope. In the age of ‘frictionless’ everything, it is born of pure friction.

All of this makes the book’s very existence remarkable – and yet none of this friction is why it must be read. It must be read for the precision of its language, for its bold experimentations with form and style, and for the endlessly original ways its author finds to express disdain for tyrants, liars and cowards. Most of all, it must be read for what Alaa has to tell us about revolutions – why 35most fail, what it feels like when they do, and, perhaps, how they might still succeed. It is an analysis rooted as much in a keen understanding of popular culture, digital technology, and collective emotion as it is in experiences confronting tanks and consoling the families of martyrs.

So, for instance, in the handful of months when Alaa was on probationary release from prison in 2019, before his reimprisonment, he shared several reflections on how the outside world had altered during his years of incarceration. When, he wondered, did otherwise serious adults start communicating with one another via emojis and gifs? Why, amidst the constant online chatter, was there so little actual discourse – engaged people building on each other’s knowledge of history and current events to create shared meaning?

In an interview with journalists at Mada Masr, Alaa observed that, ‘Getting out [of jail], I feel like we’ve gone back to the Stone Age. People speak in emojis and sounds – ha ha ho ho – not text. Text and the written word are great. So I’m disturbed.’ He describes a debate about whether veterans of Tahrir Square have anything to teach youth in Sudan, who were, in 2019, waging a courageous uprising of their own. ‘And you’re in these circles of people sending gifs and heart emojis… This medium is stifling. It’s very strange that the entire world knows that these tools and mediums are defective and they have no faith in them and are suspicious of them, but they just keep using them. There’s a need for an alternate imagination.’

This critique of the ways corporate communication platforms systematically infantilize and trivialize consequential subjects carries particular weight because Alaa is no technophobe. On the contrary, he is a programmer, a world-renowned blogger, as well as a social media aficionado with close to a million followers across platforms. 36He came to activism as a teen in the late 1990s and 2000s, surfing the liberatory promise of the pre-social media internet, a time when email lists and Indymedia networks were weaving together emergent movements across continents and oceans, converging to show solidarity for Palestine and the Zapatistas; to oppose corporate globalization from Seattle to Genoa to Porto Alegre; and to try to stop the 2003 US-UK invasion and occupation of Iraq. As a worker, the internet was Alaa’s day job; as an activist, it was one of his key weapons.

And yet in his own life, he had watched these networked technologies – filled with so much potential for solidarity, increased understanding, and new forms of internationalism – turn into tools of aggressive surveillance and social control, with Big Tech collaborating with repressive regimes, governments using ‘kill switches’ to black out the internet mid-uprising, and bad-faith actors seizing on out-of-context tweets to slander reputations and make activists markedly easier to imprison. Interestingly, it is not these explicitly repressive applications that most preoccupy Alaa in these pages. As he wrote in 2017, ‘My online speech is often used against me in the courts and in smear campaigns, but it isn’t the reason why I am prosecuted; my offline activity is.’ This insight may come from being raised in a family of revolutionaries, with his father, the renowned human rights lawyer Ahmed Seif el-Islam, behind bars during Alaa’s early years. He knows well that authoritarian states will always find ways to surveil and entrap the figures that pose a material threat to their hold on power, whether through digital tools or analogue ones.

Nor was he under any illusion that Silicon Valley was a partner in his people’s liberation. In one of this book’s most prescient passages, Alaa, writing without Internet 37access in a prison cell in 2016, predicted the Covid-19 lockdown lifestyle almost to the letter, with its attendant attacks on public education and labour standards. Mimicking the breathless techno-utopian tone, he wrote:

Tomorrow will be a happy day, when Uber replaces drivers with self-driving cars, making the trip to university cheaper; and the day after will be even happier when they abolish the university, so you’re spared the trip and can study at Khan Academy from the comfort of your own home. And the day after will be even happier still when they do away with your trip to work and have you doing piecework from home in a flexible, sharing-based labour market, and the day after will be happier and happier when they send you off for early retirement because you’ve been replaced by a robot.

This kind of analysis of the workings of capital meant that, while others enthused about ‘Facebook Revolutions’ and ‘Twitter Uprisings’, Alaa was able to remain clear-eyed about who these companies were and whose interests they served. In 2011, in an interregnum before his long prison sentences began, Alaa travelled to California to keynote RightsCon, the inaugural Silicon Valley human rights conference which now takes place every year. The crowd surely expected this hero of Tahrir to flatter them with tales of how their companies had aided in Egypt’s revolution and how they could further advance their mutual goals of democracy and liberation. Instead, as we read in a transcript of that speech, he declared himself ‘quite cynical’ about the gathering’s entire premise. Sure, it would be nice if the giants of Silicon Valley were dedicated to protecting and advancing human rights, but corporations are not really likely to do any of that.’ What they are built to do is 38

monetize every single transaction… I don’t expect either Twitter or Facebook or the mobile companies to change their business models just for activists, so that is not going to happen… What needs to happen is a revolution. What needs to happen is a complete change in the order of things, so that we are making these amazing products, and we’re making a living, but we’re not trying to monopolize, and we’re not trying to control the internet, and we’re not trying to control our users, and we’re not complicit with governments.

Over the subsequent decade, events would bear out these insights so thoroughly that it’s easy to forget that in 2011 Silicon Valley, they were close to heresy.

Rather than treating these companies like revolutionary comrades, Alaa chose to discuss the subtler impacts of social media and platform communications on daily life, the quality of discourse, and on the formation of fragile and vulnerable identities. He would return to the theme often because it has at least as much of an impact on movements as state surveillance and censorship. After all, if the groups and individuals who want political change find themselves unable to speak to each other in productive ways, what does it matter what the censors do?

When he emerged, briefly, from prison in 2019, his concerns had only deepened. And it must have been jarring. Four and half years behind bars had trained him in the painful skills of patience, disengagement and deferral. Now here he was, plunged back into the waters of instant digital gratification and continuous digital input. And he was, quite understandably, appalled. Not just by the replacement of carefully chosen words by crude emoticons, but, one senses, by the dissonance between 39the enormous stakes of the struggle for liberation against the military regime – fallen comrades, thousands of political prisoners, tortured bodies, death sentences – and the light-hearted, absurdist tone that characterizes how pretty much everything now gets discussed online, in Egypt and beyond. The subtext seems clear: he had lost his liberty, missed his son’s birth and early years, been absent for his father’s death – in large part because he believed, and the Egyptian military state agreed, that words had power. So why were so many frittering away their relative freedom of expression by treating words so lightly?

‘I feel like there has been a regression,’ he said, ‘even in two-way conversation, not just collective – in the ability to deal with complex topics.’

REGRESSION AND MATURITY

It’s fitting that Alaa would zero in on regression when he was able to re-engage online after what he described as his ‘deep freeze’. Fitting because inducing a regressed state in the incarcerated person is the goal of prisons like the one that swallowed him up, as it had his father before him. Isolation, humiliation, continuous changing of the rules, severed connections with the outside world – all of it is designed to achieve a numbed and nullified state of submission. Which makes it all the more remarkable that prison did not succeed in inducing regression in the author, quite the opposite. This book is surely testament to that.

In addition to the dexterity of its prose, as well as the acuity of its ideas, this book is remarkable for its consistentpolitical maturity. Mature because it does something very rare in the cannon of movement writing: look squarely at just how much has been lost.

Since becoming part of the alter-globalization 40movements in the late 1990s, a global network that Alaa joined as a teen, I have been struck by how hard it is, from inside an uprising’s nucleus, to even know when a revolutionary moment has passed. Among core organizers, there are still meetings, still strategy sessions, still hopes for a new opening just around the corner – it’s only the masses of supporters who are mysteriously absent. But because their arrival was always a little mysterious to begin with, that too can feel like a temporary state rather than a more lasting setback. Indeed we leftists have been known to spend years staggering around like golems inside the husks of our movements, unaware that we have been drained of our animating life force.

Alaa speaks to this eerie, undead stage of political organization, writing, with his devastating precision, of a time when ‘the revolution did not yet believe itself to be over’. Or of the period, in 2013, when the liberatory spirit of Tahrir had been supplanted by a battle between the Muslim Brotherhood and security state: ‘My words lost any power and yet they continued to pour out of me,’ he writes. ‘I still had a voice, even if only a handful would listen.’

Alaa is no longer on that kind of political autopilot. Instead, he has spent years probing the toughest of questions: Have we actually lost? How close did we get? What can we learn going forward so we stop losing? His assessments in this collection are utterly devoid either of easy boosterism or self-indulgent doomerism. He recognizes the movement’s glories, honours the life-altering ‘togetherness’ of Tahrir Square. And yet, he acknowledges, Egypt’s revolution failed in its most minimal common goals: to secure a government that rotates based on democratic elections and a legal system that protects the integrity of the body from arbitrary detention, military 41trials, torture, rape, and state massacres.

It also failed, at the peak of its popular power, ‘to articulate a common dream of what we wanted in Egypt. It’s fine to be defeated,’ Alaa writes, ‘but at least have a story – what we want to achieve together.’ Reading his earlier, more programmatic essays, it’s clear that this was not for lack of ideas. Inspired by the extraordinary grassroots process that led to the drafting of South Africa’s Freedom Charter, Alaa had a vision for how the movement that found its wings in Tahrir Square could fan out across the country and engage in ‘intensive discussions with thousands of citizens’ to democratically develop a vision for their collective future. ‘Since we’ve agreed that the constitution is one of the key goals of our ongoing revolution, why not include the revolutionary masses in its drafting?’ Trapped between top-down political parties who wanted no part of this kind of participatory democracy and by street activists who were dismissive of state power, the idea died on the vine.

‘But,’ Alaa adds to his stark assessments, ‘the revolution did break a regime.’ It defeated much of Mubarak’s machine, and the new junta that is in its place, while even more brutal, is also precarious for the thinness of its domestic support. Openings, he tells us, remain. In this way, Alaa acts as the revolution’s toughest critic and its most devoted militant. Which makes sense, given where he is. This is a writer for whom every outward communication is a risk, and who therefore cannot afford either the delusion of over-inflating his movement’s power or the finality of discounting its latent potential. He has time only for words that hold out the possibility of materially changing the balance of power.

We who have been part of those uprisings that kicked off with alter-globalization in the late nineties and early 42aughts, and that continued through the movements of the squares and subsequent climate and racial justice reckonings, could learn a great deal from Alaa’s model of intellectual honesty. Because wherever we live, there is a very good chance that we have lived through some major political losses, even if they took subtler, more sanitized forms than in counter-revolutionary Egypt. Yet many contemporary organizing models have managed to insulate us from direct confrontations with those defeats, and repressed the waves of grief from their attendant material losses. There are plenty of factors that aid in this avoidance: at times we have made no demands of power, so how could we fail to have those demands met? At other times, our demands have been so sweeping and all-encompassing that the moment of reckoning could be perpetually deferred. And, of course, there is always the next crisis demanding our attention, helpfully delaying difficult introspection once again.

This is not to say, by any means, that those who identify with this global uprising have all been on identical trajectories. When North Americans and Europeans occupied squares and parks, inspired in large part by Tahrir, we were already living in liberal democracies and did not face the same risks of a resurgent military state. When our occupations failed, many of us were able to throw ourselves into the ultimately unsuccessful campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, or in the electoral experiments of Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain. Bolivians, meanwhile, have managed to repel a foreign-backed coup and protect their left government. In short, national contexts differ, and some activists pay far higher prices, in blood and freedom, for political setbacks – inside our highly unequal nation states, and between them.43

Yet as we confront the conflagration of the global climate crisis, of surging fascist political forces, as well as the rapid consolidation of wealth by the transnational billionaire class even during a global pandemic (made exponentially more lethal by their greed), none of us, no matter where we live, have a right to claim that we are winning. Sure, left movements have changed the public discourse in profound ways in recent years, discovering just how many millions hunger for deep change. Profound reckonings have been sparked about the ongoing violence of colonialism, white supremacy, patriarchy and of course capital. Material victories continue to be won every day – in the schools, in the courts, and beyond. And yet, if we check the ledger, it is also true that we have failed to stop the steamroller of hyper-polluting and exploiting trade. We have failed to keep global emissions from steadily rising. We failed to stop the invasion of Iraq, Afghanistan or the war in Yemen. Our resistances, however heroic, however effervescent, have not brought justice to Palestine, or protected the most minimal democracy in Hong Kong. I could go on, but will spare us.

The blame lies with the perpetrators – not with the millions of overwhelmingly unarmed activists who tried to stop these juggernauts. Yet Alaa’s model here should remind us, wherever we reside, that though it may not be our fault, it is our duty to make time in our organizing and theorizing to confront our defeats. Not to wallow, but because such confrontations are our only hope of seeing the new terrain of struggle clearly.

As a committed internationalist, Alaa has words that are specifically addressed to those of us living in very different political contexts. He may have been defeated, or at least taken temporarily out of commission by a regime utterly unconcerned with the law or human rights. But 44‘you,’ he says, seemingly addressing those who are part of rights-based movements in liberal democracies, ‘have not yet been defeated.’ This is the sentence that forms the book’s title, and it sits on the page as a challenge to anyone free enough to see it.

In this challenge, he leaves us with no miracle cures. Just hard-won clarity about what many of us already know in our bones. Here are a few of his most urgent messages:

- That serious stakes demand intellectual seriousness. Resist the algorithmic pull of the trivial, absurdist and mocking, as well as the delusion that they constitute meaningful resistance. Yes, laughter is a necessary tool of survival – and Alaa can be very funny indeed. ‘I wanted to keep watching Game of Thrones’ he tweeted right before disappearing into prison, once again, in 2014. And then, on his brief release, much more darkly: ‘I’m the ghost of spring past.’ Yet he insists that, in the ‘post-truth’ age, an information ecology in which truth and meaning are valued and defended is a threat to power, which is why elites actively encourage our sense of the absurd.

- That movements must be avowedly internationalist and feminist, which means rejecting the temptations to deploy easy nationalism and the ‘trap of masculinity’ as tools of struggle. Alaa acknowledges that in the fire of revolutionary conflict, it can be seductive to believe that these forces can be harnessed towards liberatory ends. But given how thoroughly state actors have defined both The Nation and The Man, once the potent forces of nationalism and masculinity are summoned, he warns, we ‘open the door to relics of 45the past looking both to ride the wave of revolution and steer it off its course’.

- That movements need a captivating vision of the world they are fighting for, and not only rage at the system they are desperate to overthrow. ‘Our rosy dreams will probably not come to pass,’ he writes, with typically brutal honesty. ‘But if we leave ourselves to our nightmares we’ll be killed by fear before the Floods arrive.’

- That freedom, however limited, must be exercised to its maximum potential. Alaa understandably rejects the common formulation that Egypt is one large prison: no, he writes, prison is a very specific place, with specific cruelties and barbarities. And while it’s true that many liberal freedoms are denied to all Egyptians, the freedoms possessed by those on the outside – control over their bodies, time and relationships – are immense compared to the life of an incarcerated person. Still, while refusing the idea of prison as metaphor, he is, throughout, preoccupied with the ways technically free people are nonetheless confined and entrapped – by black box algorithms and, more profoundly, by the way capitalist logics constrain imaginations, preventing contemporary movements from meeting our most urgent crises.

- That bodies, movements, and the natural world are capable of regeneration – even if past losses and wounds mean that they regenerate into something different, more scarred and less conventionally perfect. We must be willing to become, he says, borrowing from Donna Haraway, a new, more beautiful 46kind of monster, ‘for only the monstrous can hold both the history of dreams and hopes, and the reality of defeat and pain together.’

It is this kind of softness that makes Alaa an evolved movement leader: his refusal to romanticize or glorify imprisonment or suffering in any way, his insistence on his own fragility, his right to sadness. And yet, no matter the physical and psychic mutilations, his belief that healing and regeneration remain possible.

And there is a final, related lesson. Our movements must urgently defend the integrity of the body. We must defend all bodies against imprisonment, indefinite detention, torture, rape and state-sanctioned massacre. Because we are human, and without a shared belief in the body’s right to integrity, transcendent movements will continue to be crushed by the raw power of states willing to inflict violence without limit. And that is precisely how we lose voices like Alaa’s to the muffled darkness of the prison cell. It cannot stand. #FreeAlaa.

Naomi Klein, July 2021

INTRODUCTION

Alaa Abd el-Fattah has spent seven of the eight years since the counter-revolution led by General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in prison. He is in prison for his ideas and his words. Here, for the first time, a collection of Alaa’s work is brought together, assembled and translated by his family and friends.

The reader is introduced to Alaa at the peak of the energies unleashed by the 2011 revolution in Egypt as he surveys the constitutional history of South Africa. Writing for a national broadsheet, al-Shorouk, he is setting the stage for the following day’s launch of the ‘Let’s Write Our Constitution’ campaign, an initiative in mass democracy inspired by South Africa’s Congress of the People of 1955, and an attempt to turn the opportunities following the fall of Mubarak four months earlier into irreversible legislative gains.

Three short months later, the military kill twenty-six protestors at Maspero and we follow Alaa into the massacre’s aftermath in ‘To Be With the Martyrs, for that is Far Better’, his account of the night spent in the Coptic Hospital, fighting for autopsies to be performed. Two weeks after its publication he is summoned by the Military Prosecutor.

Imprisoned while his wife delivers their first child, Khaled, and his mother is on hunger strike, Alaa’s writings from prison in this period are urgent and impassioned yet always connected to broader political developments and attuned to their minutiae.

Following Alaa’s release, we find ourselves in the swirling waters of 2012–13: relentless street protests and industrial actions, parliamentary and presidential elections, constitutional crises, the Muslim Brotherhood’s 48victory and catastrophic year in power. In this period Alaa writes very few long-form essays, instead tweeting and posting to Facebook, hosting public fora, appearing on television talk shows and speaking at rallies. We tried to use Alaa’s social media output to tell the story of 2012–13, but we must bear in mind the sheer volume of his output. He has tweeted a total of 290,000 times since 2007 – about 100 books’ worth of tweets.

Our social media selections are an attempt instead to show how he uses the internet: as a medium not only for transmission outwards, but of collecting information, combining and disseminating, as a space for debate, a personal diary, a public diary, a podium and a comedy stage. Alaa writes relentlessly, his brain always engaged with a multitude of topics simultaneously, his patience for engagement with other people seemingly inexhaustible: there is no opinion that is not worth engaging with.

August 2013 brings the massacre at Rabaa el-AdaweyaSquare in Cairo. The public killing of hundreds of supporters of ousted Muslim Brotherhood President Mohamed Morsi is designed to silence a country that considered itself in an ongoing state of revolution. But Alaa refuses to be silenced, and his Facebook posts, ‘Above the Sound of Battle’ ‘What Happened at Abu Zaabal?’ and ‘You Know the Killing Was Random’ are widely remembered as beacons in the reeling darkness of those days.

In August 2012 Mohamed Morsi had appointed General Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi as the new Minister of Defence, replacing the aged and unpopular Field Marshall Hussein Tantawi. Tantawi had held the position for the previous twenty years, had overseen the removal of Mubarak the previous year, and as head of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) had been de-facto in charge of the country through the transitional 49period up to Morsi’s electoral victory. Tantawi’s removal by the newly elected civilian was greeted as a revolutionary act – but the president had sealed his own downfall by elevating the ambitious and ruthless Sisi to the position from which he would soon overthrow him.

Once the police had decimated the Muslim Brother-hood – with the massacre at Rabaa, the round-up of the leadership, the arrest of thousands of men and women, and the total clampdown on media – they turned their attention to the revolutionary youth. A colonial-era British law outlawing protest was re-animated and turned against the street, and in November 2013, three months after Rabaa, Alaa was arrested again. He was among the very first targets, along with two of the co-founders of the 6 April Youth Movement, Ahmed Maher and Mohammed Adel.

In this next spell inside, Alaa writes four major essays in four months (‘Graffiti for Two’, ‘Autism’, ‘Everybody Knows’ and ‘Lysenko Country’). His pieces are read widely, published in multiple newspapers simultaneously, reported on as news in the national press. The revolution did not yet believe itself to be over. But the machinery of the state, the police, the judiciary, the media, have set to work on grinding the disobedience out of the people. Alaa’s trial, ostensibly for organizing a protest, is long and complex. One judge recuses himself, and his replacement has Alaa arrested as a fugitive as he stands outside the courthouse, barred from entering. Over 2014 he is released briefly twice – for two months in the spring, and one month in the autumn. But it was in the summer that Alaa’s father died.

Ahmed Seif el-Islam was a key figure in his son’s life. A member of a militant communist cell who was imprisoned and tortured in the 1980s and emerged from 50incarceration with a profound attachment to the idea of the law and the opportunities that it might present, even within a dictatorial police state. He went on to found the Hisham Mubarak Law Centre and his clients ranged from the young men charged with the Taba terrorist bombings of 2004, to dissident bloggers, to striking workers, to the men persecuted for their perceived sexuality in the notorious Queen Boat Case. The positions he took, and the organizations he helped build played a part in creating the conditions for the 2011 revolution. But, in 2014, exhausted by his years on the frontlines, and with two of his children in prison (Alaa’s sister, Sanaa, had been arrested recently at a protest for prisoners), his heart gave out.

Eighteen days later, Alaa was briefly released from prison, long enough to deliver an address at the memorial for his father, but one month later, on 27 October, was sentenced to five years in prison. Inside, he went quiet for a year.

He appears for us again in 2016 – first with a short reflection written for the Guardian, then with three major pieces on the changing economics of the digital revolution. ‘The Birth of a Brave New World’ trilogy is a breathtaking display of how wide-ranging and original a thinker Alaa is. Written from prison, almost entirely from memory, he writes a precise and prescient critique of the relationship between Silicon Valley, venture capital, labour and technology that remains relevant and illuminating. Alaa’s imprisonment does not only deprive Egyptians, or Arabic speakers, of one of their most important voices: we are all the poorer for his absence.