9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Born in Shanghai and shipped to England as a child, Peter Whitehead then made his way to Australia, solo, at the age of 13 in 1938, in order to save his family money.

Alone and working in near slave-like conditions as a farm labourer, Peter learned the art of breaking wild horses and so began a lifelong love affair with animals.

After wartime service as a horse breaker for the army and a gunner on a Liberator bomber, Peter headed to Africa and a richly varied career as an agricultural officer, national parks ranger, big game hunter, animal wrangler and rancher.

He worked on the sets of several big-name movies, including

Hatari! with John Wayne, and handled lions for the smash hit film,

Born Free.

Peter survived two aircraft crashes, as well as encounters with man-eating lions, zombie witches, and killer hippos, and nearly drowned in a crocodile infested river.

Along the way, he also helped save an endangered species and found a woman who would put up with him.

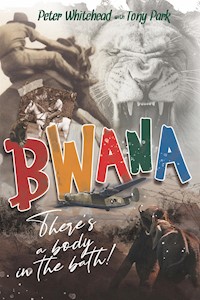

Bwana, there’s a body in the bath is Peter’s story of nearly a century of incredible adventures.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

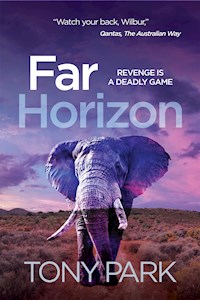

BWANA, THERE’S A BODY IN THE BATH!

PETER WHITEHEAD

TONY PARK

CONTENTS

Foreword

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Acknowledgements from Tony Park

Also by Tony Park

About the authors

FOREWORD

It is a great honour to be invited to write the preface to the story of such a remarkable man. As you will read, my Uncle Peter has led an action-packed and colourful life. I am so delighted that he has finally managed to get his story written, after much nagging.

He first came into my life in England, when I was about seven. I was ‘born on the back of a horse’, and we instantly hit it off. We share a lifelong passion for horses, dogs, parrots and Africa.

For a time, I lost track of him, during his wanderings in Africa, but I never forgot him. I managed to track him down there with the help of my husband, who had heard tales of Peter Whitehead in Kenya, and was very keen to meet him.

After my mother, Wendy, Peter’s little sister, died, Uncle Peter became my rock. He is now my ‘go-to’ for wise advice on so many different problems in life. Although we live at opposite ends of the world, he calls me on FaceTime (sometimes catching me in the shower, causing a mad dash to turn the camera off) and between us we are able to put the world right.

At times in his life, as you will read, Peter has overcome real hardships, and shown great resilience and true grit to survive. His philosophy has always been ‘just get on with it’, and he has.

I hope you enjoy this amazing story of the life and times of Peter Whitehead.

Anita Harrington

The Countess of Harrington

PROLOGUE

KAFUE NATIONAL PARK, NORTHERN RHODESIA, 1957

It had been a good flight, apart from the severe turbulence, and crash landing in man-eating lion country.

The pilot, Ted Lenton, and Gerry Taylor, the provincial game officer, were in the front two seats of the Auster, a fragile little single-engine relic of the Second World War that had been designed for artillery spotting. As the youngest and least important I’d been relegated to the rear seat.

At the end of the dry season the hot, late afternoon air was rising up off Africa, baking below us. Soon the rains would come, spectacularly violent thunderstorms heralding a green revolution for the thirsty brown lands below.

The bumps got bumpier and my head was threatening to punch a hole in the roof. I’d flown during the war and had seen what Mother Nature could do to aircraft far larger and more robust than this one. I reached down and wrenched the seatbelt tighter.

All of us had our eyes peeled for likely places where the Kafue River could be crossed easily. I was watching as best as I could, out of my tiny side window and between the two men up front – after all, this little diversion from the flight plan had been my idea.

Gerry had arranged this weekend ‘jolly’ that we were on, a mix of business and pleasure at my permanent camp near the Kafue Hook, a bend in the river, to welcome a new member to the Northern Rhodesia Game Department to our province. Ted was giving his services for free, in return for the promise of some fabulous fishing; the charter of the aircraft was another of Gerry’s fiddles.

The new appointee, together with all the staff and gear we needed for a weekend’s fishing had been sent on ahead by land, leaving Mumbwa early in the morning for the 120-plus kilometre journey to the camp. Our original flight plan called for us to leave Mumbwa airstrip just after lunch and fly directly up to my camp at Myukweukwe, close to the pontoon crossing at the Hook.

I was 34-years-old by this time, the game ranger in charge of the central section of the Kafue National Park in Northern Rhodesia, which would, some years later, become Zambia. It was during our lunch that I proposed we revise our flight plan, unofficially, in order to look for a suitable site to put a pontoon in to cross the Kafue River between my central section of the park and the northern section under the control of my opposite number, Barry Shenton.

At that time, a meeting between Barry and myself entailed an arduous overland journey in the order of some 300 kilometres, whether we attempted the Mumba-to-Mankoya Road route, or the northerly one from Mumbwa to Kasempa. Both entailed long sections of bush-bashing. If we could find a suitable site for a pontoon crossing, we could cut at least 200 kilometres off the journey.

I spread out the map and showed them my revised flightpath.

‘Let’s head a few points west of north and cut the river here,’ I pointed to a point about 30 kilometres upstream of the area I considered most likely to afford a crossing, ‘then let’s fly as slowly as we can downstream, and have a look at any possible sites. We should still get to Myukweukwe around 4.30 or 5pm – plenty of time for a quick hook or two in the water.’

After that it would be fresh fish for dinner, followed by a convivial evening of drinking and tall stories.

My base at Mumbwa was a cluster of about a dozen houses in varying degrees of decrepitude ranging from the game ranger’s allotted accommodation, which had been condemned as unfit for human accommodation some 20 years earlier, to the District Commissioner’s house, which had been updated by the Public Works Department a few years earlier to include such up-market luxuries as running water, a flush toilet and a small generator to provide electricity.

The ‘boma’, the collective name for our settlement, believed to be an old acronym for British Officers’ Mess Area, was home to a fluctuating population of about eight men, including the District Commissioner (DC); a couple of District Officers (DOs); a medic; a police officer; and representatives of technical departments, including agriculture, veterinary, public works and game and tsetse fly control. Apart from the DC, medic and one of the DOs, who were married, the rest of us were young and single, with all that entails.

Our houses were located just west of the district administration buildings, where the road divided, the left fork curling round the east end of the airstrip through three seedy little trading stores – one run by a South African, Jukes Curtis, and the other two by Indians. The road then carried on to Mankoya, via the Kafue Hook, some 250 kilometres to the west in Barotseland.

After lunch, we headed out to the Auster, squeezed in and took off. Besides making it easier for me to liaise with Barry there was another, less urgent benefit that could possibly arise from a more efficient crossing of the river, namely tourist development.

If the park had more roads and easier access, visitors might come, but that was a long way off as the area was literally in the middle of nowhere and plagued by the most ferocious and liberal quantities of tsetse flies, many of which carried human trypanosomiasis – also known as sleeping sickness.

To further discourage humans and habitation, the area we were now flying over was home to a particularly unpleasant race of lions, addicted to human flesh. So dangerous had these man-eaters become that the colonial administration in the early 1930s had relocated the indigenous population, a whole tribe under Chief Kabulwebulwe, further west to the safer areas of Barotseland. This, coincidentally, suited the management of the newly-designated National Park.

Having arrived at the river approximately where we intended, Ted turned the nose to the west, reduced altitude to about 200 feet, and we set about looking for a likely spot for a river crossing.

The Kafue National Park is about the same size as South Africa’s flagship game reserve, the Kruger National Park, itself often compared in area to Israel or Wales, and by that time already establishing itself as a tourist destination of note. The major difference was that Kafue was in the middle of nowhere, a remote, inaccessible tract of virgin bushland and sweeping plains. It boasted large herds of waterbuck and impala, as well as lesser-seen antelopes such as Lichtenstein’s hartebeest and the majestic sable and roan.

‘Looks like a good spot down there,’ Gerry said after about 45 minutes of flying, pointing ahead through the cockpit windscreen.

Ted pushed the stick forward into a gentle dive and only levelled off when were so low that the wheels of the fixed undercarriage were almost skimming the glittering surface of the Kafue River below us.

The river was about five hundred metres wide at this point, punctuated here and there with the rounded backs of hippos. A herd of puku, a shaggy-coated, yellow-brown antelope, bounded away as our shadow passed over them. Ted tracked along the northern bank of the river while he and Gerry searched for signs of shallow water and approach paths, eroded areas where game came and went to drink and where access by motor car might one day be possible.

The spot Gerry had indicated looked promising, but we would need to check the southern bank so Ted pulled back on the stick, turned and circled about. He dropped down again and just as we levelled out the engine coughed.

‘Shit,’ Ted said.

Next came a hiccup and the engine stopped. A moment later it started again, providing us all a moment’s relief, but then it coughed again and began running erratically, vibrating and juddering in front of us.

Ted’s spare hand flew over the controls like a one-armed paper hanger but nothing seemed to be happening. Before he lost too much more momentum, Ted pulled back on the stick, pushed on full-left rudder and just managed to clear the top of the trees running along the side of the river.

As worrying as the situation was, Ted was thinking, and he was doing the right thing. If we had put down in the Kafue River the crocodiles would have feasted on anything that was left of us after the fiercely territorial and aggressive hippos had finished chomping the aircraft and what was left of us in their massive jaws.

Give me lions, any day, I thought.

Just as it looked as though we might gain enough altitude to search for a smooth, open vlei to land, we stalled. The Auster hung, nose up, for a heartbeat, then dived for the ground, nose-first.

Luckily, Ted had only been able to climb about fifty feet before the engine finally conked out, but we still hit the ground with an almighty bang. Gerry and Ted, unlike me, had not been affected as badly by the turbulence and so had not had time to tighten their safety straps, resulting in both being a little bent on impact. They were conscious, however, and staggered out of the Auster.

I smelled fuel and, unscathed thanks to my safety straps, clambered between the front seats and was out of the aircraft like an eel swimming upstream. Looking out for each other, we all hobbled or ran as far as we could from the Auster, expecting it to burst into a ball of flames at any second. We threw ourselves down on the ground and waited.

Nothing happened. A dove cooed nearby; Gerry slapped at the first of a promised aerial armada of tsetse flies.

‘Let me go see what I can find,’ I said, as the other two slumped in the shade of a tree, assessing their injuries. As the least battered of the three of us it was up to me to do what I could for the common good. I went to the aircraft, swatting at flies as I walked.

The Auster had buried its nose deep into the dirt; the airscrew had shattered into a thousand pieces. The wings were askew, but it was clear from the ease we had exited that getting back in was not going to be a problem, once I was sure it was not about to explode in a ball of flame.

Sitting vertical as it was, the wreck would be no use to us as shelter and too small for all of us to sleep in, anyway, so I began rummaging about for anything that might be of use to us. We hadn’t brought a firearm with us - they had all gone up in the road convoy. Our plan, had we stuck to it, was to fly as light as possible into a fully equipped camp.

From the battered aircraft I took the first aid kit, a small crash axe, designed for getting out of tight spots, such as a broken aeroplane, some tinned bully beef – to be consumed only in the direst of emergencies, a tin of powdered milk and, most importantly of all, some tea.

‘Here you go, fellas,’ I said as I handed my scavengings to Ted and Gerry, who set about patching themselves up as best as they could. I then opened the can of milk powder and took the bagged contents out. This gave me a handy container for water, so I went down to the banks of the river. On arrival I saw the furrowed tracks in the sand where a crocodile had eased itself back into the water, perhaps, on hearing my footsteps. Keeping a wary eye on the water I went to the edge and filled the can.

When I came back, I got a fire going and put the billy on, deciding that a cup of tea was the first priority before we did anything else. While we waited for the billy – the empty milk tin – to boil, I helped the other two dress their wounds.

We had a council of war and took stock of our supplies. Our ‘emergency supplies’ kit included, amongst other useful bits and pieces, some fishing line and hooks, but no tea cups. Once it had boiled, I brewed up some tea. We passed the billy between us, sipping from the hot can. I must say, the tea helped raise our spirits.

Ted looked at the sun, half way down to the horizon. ‘Won’t be long until it’s dark.’

It had been about three in the afternoon when we crashed and light would not be long with us. While the other two rested I put on another can of water, took the axe and began organising us some shelter.

Near to where we were was a big Kigelia africana, a sausage tree. Lush and shady, the tree was named after the long bulbous, hard-shelled fruits it bore, which, shaped like a sausage, averaged the size of a grown man’s forearm. They were no use to us as food, though baboons ate them. Had it been the wrong time of year they would have been quite a threat – a hit from a falling ‘sausage’ could do quite a bit of damage.

Next to the tree, and of more interest, was a large termite mound with a rich thicket of masakasaka bush filling the space between the two. Using the axe, I started hacking into the foliage, carving out a little cave in the dense vegetation.

I kept the branches and foliage I cut out of the hollow and arranged them into a spikey palisade around the front of the opening, creating a boma large enough for us to stretch out in and light a fire. I then scoured the bush around us for wood and stacked enough to last through the night, inside the enclosure.

Once all was ready, I called the other two, and showed them their new home, then got another fire going. It was now nearly dark. I sat on a log in front of the flames, thinking.

‘I’ve got a pretty fair idea where we are,’ I said, ‘and no one’s going to get to us for at least three or four days - and that is if they do find us.’

‘We need a plan for that long,’ Gerry said.

‘Do we stay here?’ Ted asked. Conventional wisdom had it that staying near the site of a wreck was the best course of action. ‘Anyone searching for us is more likely to see the wreckage than one of us.’

I slapped at a late-flying tsetse fly. At least they would disappear with the sun. ‘I reckon the Mumbwa-to-Mankoya road’s between thirty and forty miles south of us, as the crow flies. I’m OK. I could walk it.’

There was some debate about that. It was fiercely hot during the day and easy to get lost in the bush, the others pointed out. The trees to our west were swallowing the last of the sun, tinged red through the dry season’s dust.

‘I’d walk at night – starting tonight.’ I pointed up at the heavens. ‘All I’ve got to do is follow the Souhern Cross; I can navigate by that.’

While we discussed our fate an orange full moon was starting to climb in the sky. It was a good sign, I thought, and would be bright enough to allow me to watch out for danger. I dragged some more logs on to the fire, readying myself to set off.

I turned my back on the flames, so as to prepare my night vision, and from the comparative safety of our flimsy natural fence of foliage I stared out at the bush.

‘Movement,’ I hissed.

‘What is it?’ Ted asked, from the cave in the vegetation on the other side of the fire, where he and Gerry were lying.

By the light of the moon, which I thought would keep me safe, I saw the silhouettes of three animals moving, their bodies slightly paler than the backdrop of vegetation.

‘Hyenas?’ I said, ‘Three of them.’

The spotted hyena is a brazen animal; it’ll sneak up and steal the chop off a braai, but by the same token, if confronted by an angry yell or a hurled rock it will slink away. A number of them together, however, might be a different proposition.

The animals were no doubt attracted by the firelight, perhaps the first they’d ever seen in this remote part of the park. They started coming closer, looming in size.

‘We’ve got visitors, I called to the other two.’

As they came closer my heart skipped a beat. These animals, I now realised, were not hyenas after all.

‘Shit, man,’ I said, as the largest of the trio, a male, gave a growl, broke ranks and charged at our flimsy boma.

‘Lion!’

1

SHANGHAI, 1929

Chinese servants screamed with a mixture of amusement and annoyance as I hurtled down the laneway on my Fairy tricycle.

The milkman, caught unawares, had to jump out of the way to avoid himself and his bottles being cleaned up by a five-year-old.

My kingdom, before school attempted the impossible task of civilising me, was the back alley. Behind the genteel, westernised suburban street on which we lived, I tried the patience of whichever servant had drawn the short straw to supervise me that day and reigned like a tiny, tyrannical emperor. I mixed with the amahs and delivery boys, played with their children, and learned to speak Chinese, badly.

Here, people gossiped and spat and took their meals crouched together. A sewage drain ran along one side of the lane and on this day of play the concrete cover outside the kitchen door of our house had been removed, where workmen were engaged in the unenviable task of clearing a blockage. A grimy place at the best of times, the alley was positively ripe in the sticky July heat.

‘Out of my way, out of my way,’ I called as I pedalled down the laneway.

The Fairy tricycle was not made for little people at the end of the garden, but, rather, for short humans. Following on from the success of the Penny Farthing in the 1880s, Fred Colson of the Colson Corporation in the United States had the bright idea that children might quite like to ride cycles; without a ladder the Farthing was way out of reach to someone my size, and a death trap. His ‘Fairy’ line was low to the ground with a cross bar almost down at road level – perfect for a little terror like me.

As I screamed along, I might have evaded the milkman, but the baker’s delivery man, sick of my antics and determined to teach me a lesson, reached down as I swerved past him and grabbed my little trike by the rear and lifted it into the air.

‘Let me go, let me go!’ I wailed, my little legs pumping furiously but impotently as various hawkers, staff and delivery folk laughed uproariously and pointed at the white boy squealing like a piglet.

The baker’s man simply did as I had commanded and dropped me, but my back wheels were spinning at such a furious rate that I shot off like a Chinese firecracker, straight into the open sewage drain.

‘Aieee!’ our Amah shrieked as others covered their mouths with their hands, agog at the sight of me landing, cycle and all, with an almighty splash and going down like a submarine in crash dive mode

One of our servants, probably the unfortunate charged with babysitting me, sounded ‘panic stations’ as workers, passers-by and even those who found the whole thing hilarious, crowded around.

I looked up at them, white eyes peering out from a mask of effluent resulting from the lavatorial waste of the area.

I was fished out and stripped naked on the spot, amidst the cooing, chuckling, screeching denizens of the alley world. A tap was turned on and the next thing I knew I was being hosed down, pummelled from head to foot with cold water.

All of our house staff had now been alerted and had gone into full damage-control mode.

‘Inside, inside!’ someone hissed.

My filthy, sodden clothes were gathered and I was furtively sneaked into the house via the servants’ entrance to the staff bathroom where hot water was drawn and every inch of me was again scrubbed vigorously and repeatedly until the last evidence, either visual or olfactory was eliminated from my, by now, pink skin.

A servant was dispatched to my room to get fresh clothes. There was more tutting and fussing by the high-speed pit-crew of maids and assorted other servants as my hair was combed, my buttons done up and shoes laced. Meanwhile someone, presumably one of the male staff members, had been delegated to the unenviable job of fishing my Fairy cycle out of the cesspit, hosing, scrubbing and cleaning it, then sneakily wheeling it around to its normal resting place at the front of the house.

When I was judged to be pristine, I was shepherded quietly downstairs from the servants’ quarters and propelled with a gentle shove in my back into the drawing room, where my mother sat, reading and taking tea.

‘Hello, Peter,’ she said, looking up from her magazine, ‘are you alright, dear? Have you not been out playing? You’re looking unusually clean for this time of day.’

As the precursor of any future material benefits I might receive from the hands of lady Luck, I was born on Christmas Eve, 1923, in a nursing home in Shanghai’s French concession. My parents were doing well and could easily have afforded to give me a double helping of presents each December 24, to make up for my lack of enterprise in choosing such an inauspicious day to enter the world, but it was never to be. Father was far too serious for that sort of thing.

Charles Whitehead was 37-years-old by the time I, the third of four children, came along. He was a partner and the managing director of a company importing and installing cotton manufacturing machinery into the developing cotton industry of a growing China.

Shanghai was booming. On the city’s bustling streets white men in winged collars and bow ties marched to and from business meetings or lunch, slyly eyeing elegant Chinese women sporting short, wavy, western hairdos and wearing tight-fitting cheongsams, demurely covering their necks, but split to the thigh at each leg. The pampered wives of Europeans, clad in the latest flapper fashions, perambulated idly along the Bund, the wide walkway and office-lined road running alongside the broad Huangpu River, or made their way to a game of bridge or a bar.

Vessels of all sizes from local junks to passenger ships and Naval Dreadnoughts lined the docks. Gleaming limousines driven by chauffeurs in hats hooted past modern trams and ancient rickshaws in a city that prided itself on being a mix of the Paris of the East and the New York of the West.

It was a good life for the residents of the International Settlement, and I have memories of my father in a dinner suit, my mother in the latest frock, setting off for functions and coming in long after my bedtime.

The worst that had come of my spectacular immersion in the sewer was a case of conjunctivitis, or Chinese Pinkeye, as it was known; this kept me confined to the dark interior of the house for a while, but I was busting to get out. The only other childhood disaster I recall was contracting scarlet fever in 1931 and being locked up in the hospital for infectious diseases.

‘Hello, Peter!’ my family – mother, father and little Wendy – called from the hospital grounds below as I leaned out of an open window on the upper floor, looking down at them and waving. That was as close as I got to a visit while I recovered.

Horses have always loomed large in my life and my love and fascination for them go back as far as I can remember. The Shanghai police force included mounted Sikh troopers and I recall a gigantic, magnificently bearded and moustachioed gentleman, replete with turban, colourful uniform and glittering finery which included a sword and a big pouch containing a revolver strapped to his waist. From his Olympian height astride his horse, he would reach down and hoist my little sister, Wendy, or me up on to the pommel of his saddle and parade us down the street, to the envy of the other neighbourhood children and the chagrin of their more conservative parents who didn’t approve of such goings-on.

My parents had been married shortly after the end of the First World War. My mother, Mabel, was the youngest daughter of a successful farmer/horse dealer and as an accomplished horse-woman herself, encouraged her two younger children to emulate her with the help of a riding stable owner, Miss Perrin, who operated her business not far away from our house.

When I was younger mother had taken my elder siblings, Glen and Mary, and my younger sister, Wendy, and me back to the UK for a while. Glen and Mary were enrolled in their respective schools and left in the care of mother’s older spinster sister, while mother, Wendy and I returned to China.

Back in Shanghai both Wendy and I were introduced to the educational process via a primary school located in Bubbling Well Road, later renamed Nanjing Road. The tree-lined, agreeable thoroughfare had been described as the most beautiful in Shanghai and led to the impressive Jing’an Temple. Among the many other children at the school was a little girl called Mary Hayley Bell, who I would meet again several decades later, when she and her subsequent family had become household names in Britain.

One clear memory I have of that time is of being obsessed with a game played with glass marbles, which entailed flicking the marbles through little holes cut in a cardboard box, though what happened to the marbles after they went through the little holes escapes my memory.

Another vivid memory is of diving for coins thrown into the water at the Municipal Swimming Pool which was located in, or very near, the Racecourse.

In 1931 Japan invaded Manchuria, the first step in what would be a protracted onslaught against China and, later, the South Pacific. In January 1932, Japan created an excuse to attack Shanghai.

Ultra-nationalist Japanese monks started riots in Shanghai, shouting pro-Japanese, anti-Chinese slogans. This prompted retaliation by Chinese mobs, leading to the killing of a monk. The Japanese used this and further street fighting as an excuse to attack the Chinese parts of Shanghai – not the foreign settlement where we lived – with carrier-borne bombers and later, ground troops.

Fighting raged between the Japanese and Chinese armies outside of our enclave, but the western powers, wanting to protect their business interests in China, and not keen on a war with Japan, helped negotiate a ceasefire and peace by May. It was, however, only a matter of time before the Japanese came back.

I am not sure what prompted the decision - perhaps the turbulent relations between China and Japan, the developing financial depression or the fact that I was now reaching the age when a move up from primary school was due – but Wendy, mother and I were shipped off back to the UK.

We boarded a vessel of the German Norddeutscher Lloyd shipping service, our mission to set up house and attend to the educational requirements of the now consolidated family. My father remained in Shanghai to attend to his business.

As I waved goodbye to my father, I had no idea it would be the last time I would ever see him.

I took aim down the barrel of the 16-gauge shotgun, lining up a fat pigeon in the green hedgerow.

There was a chill in the air, the sky leaden and threatening rain yet again. I had thought England would be a prison, but I had managed to find an escape – the country. The weapon wavered in my skinny arms, then I squeezed the trigger.

Boom.

The butt of the shotgun slammed into my shoulder, nearly knocking me over. The pigeon flew away. I had missed, but I was having the time of my life. Not every bird I aimed at was as lucky.

From Shanghai we had gone to live in the small town of Royston, in Hertfordshire, where both sides of my father’s family were part of the local community. Glen, Mary and I commuted to school in Cambridge, in the neighbouring county, each day by train, while Wendy, my partner in crime in Shanghai, was now attending primary school locally.

I can’t remember much of my time at the Lower School other than playing soccer rather than rugby and being enrolled as a very reluctant member of the Cub Scouts. Scholastically, I must have done something right as I actually won a prize – a book called ‘Gods, Heroes and Men of Ancient Greece’ by Dr. A.L. Rowse, who, in his earlier days had apparently been a pupil at the school.

The pleasant atmosphere of lower school changed dramatically on my graduation to the upper or ‘Big School`

At the Big School, as a student, I was an unmitigated disaster and a total waste of the fat fees they charged for not doing anything more than providing me with a place to spend the day during term time

Somehow, I had incurred the antipathy of a number of the masters, especially the headmaster who missed no opportunity to humiliate me publicly, admonishing me for some real or imagined misdemeanour at assembly.

The headmaster looked down his beaklike nose at me. ‘Whitehead, my study, Thursday at noon.’

He took every opportunity to administer corporal punishment in the form of a length of a six-millimetre bamboo cane, with a curved handle, taped for a better grip, which he applied with great enthusiasm to my nether region. The canings were a regular feature every Thursday, designed to improve my ability to absorb the wisdom dispensed in the classrooms. From my point of view, the only tangible effect was to make eating my lunch uncomfortable.

I understand that sometime after I had left the headmaster’s care, he was hospitalised for gastric ulcers, which may have accounted for his behaviour, but it certainly didn’t help me, or change my view of him. As a form of encouragement for me to apply myself to my studies it was a total failure, a conclusion he hadn’t come to even after more than a year’s trial.

Generally, my view of the school and its staff was that they were a bunch of myopic, self-righteous sadists, happy to extort money from my parents in return for a licence to inflict corporal punishment as and when they felt like it.

My escape, as always, was the countryside.

When Wendy reached the age to attend her sister’s Lower School the family moved from Royston, briefly, to the village of Shelford, before moving on to the more rural village of Fulbourn. There, we took over a delightful old wing of what was once quite a grand house called Old Shardelowes.

For me, this was a dream home, situated as it was on the very outskirts of the village, surrounded by open fields and woods with quite a big farmyard between us and the village. Needless to say, my mother was dragooned once again in to making representations to the farm owner to allow me to ‘assist’ on his farm whenever I had time away from school. He must have been a very kindly man, as he agreed and for the next two years I toiled away quite happily under his ‘supervision’.

To make Fulbourn an even more acceptable place, the father of one of my friends from school, Bob Lacy, also farmed there, as well as training a few race horses. Bob rode in the mornings before leaving for school, an activity I would have given my soul to join him in, but alas it was not to be. Bob, a year older than I was, stood just over five-feet tall and all up dripping wet barely tilted the scales at six-and-a-half stone, whereas, I, a year younger, was already approaching six feet and weighed just over 10 stone.

Yet another benefit of life in Fulbourn was that across the road from our house, in what had once been a labourer’s cottage, lived the local handyman and reputed poacher, Jim Plum.

Jim and I became great friends, with him assuming the mantle of mentor in the field arts of rural England, as defined by those with very little money. Under Jim’s tutelage, I learned to shoot, snare and trap, pluck, skin and prepare all manner of legal and illegal game in and out of season.

In doing so I helped mother stock the table, even if she was a little embarrassed to learn where the bounty had come from. Guilt by association does not seem to have been too evident, as my farmer mentor, who worked all the fields around our house, often used to loan me his 12-gauge shotgun.

Ostensibly, I was to wander about the fields during autumn and winter to shoot wood pigeons, rooks, rabbits and other vermin. However, when no one was in sight, if something more tasty wandered into my sights the offer would be accepted, and the resulting victim stuffed down the back of my coat, or hidden in the hedgerow for retrieval later, a-la-Jim’s teaching.

‘Watch him, boy,’ Jim said, standing close by me as we watched a pheasant, ‘and don’t forget to lead him. Now!’

As the bird, deliberately spooked, took off, madly flapping its wings, I did as Jim had taught me and aimed slightly ahead of it, allowing for the time it would take the pellets to reach it. I squeezed the trigger, ready for the recoil.

‘Good shot, boy!’

Surrounded by farmland and remnant woods, I began to find something of my true calling. I was a willing farm labourer – anything was preferable to the classroom. I had decided that the two things in life I wanted to pursue were rugby and farming. Animals, in particular, intrigued me.

The farmer wasn’t complaining. I was more than happy to muck out stables, cow byres, and pig sties. For me it was bliss – give me the smell of manure and a bit of physical labour over the scratching of a pen nib on paper, or the swish and thwack of the headmaster’s cane, any day, I thought.

In time, I graduated to leading horses here and there, and driving cattle to and from the fields. Eventually, as I got older, I was given more responsible jobs, such as harrowing fields with a team of two or three horses on my own, or taking the horses into the village to get shod. In the summertime during hay-making and grain harvesting, I would lead the horse and cart whilst the men built huge loads onto the cart which were then roped down. The horse and cart would then be driven to the farmyard for unloading onto the stack or tipped into the barn.

For me it was an idyllic existence, and no doubt kept me out of mischief from my mother’s point of view. The farmer seemed more than happy to have an unpaid hand around to do some of the less technical work.

Altogether, life at Old Shardelowes couldn’t be bettered. During the season, I was able to play rugby to my heart’s content at school; the sport became, and still is, an abiding passion.

I also learned the art of cutting school, escaping whenever the opportunity occurred. Out of school I had all the work and entertainment a boy could dream of; the only fly in the ointment was the attentions of the headmaster at regular intervals

By the age of 13, I felt as though school would never end; however, ironically, my salvation from the crushing boredom of the classroom and the sadistic ministrations of the headmaster came at the hands of the Imperial Japanese Army.

I was upstairs in my bedroom when the phone rang. I heard my mother answering the call, talking away, but then something about her tone of voice changed.

‘No!’ she yelled down the line.

When I got to her she was sobbing.

‘What’s wrong, mum?’

‘Your father… the Japanese have invaded Shanghai and he’s been captured. Whatever are we going to do, Peter?’

My mother was no doubt worried about my father, and the fate that awaited him as a civilian internee of the Japanese, but she was also, quite rightly, worried about us. Father had been our source of money as he had continued to work, but now we were suddenly without means.

While this latest conflict between Japan and China had been sparked by another seemingly trivial incident – a missing Japanese soldier, this time, and an exchange of gunfire over him at the Marco Polo Bridge in Wanping – it led to all-out war. Unlike the relatively short conflict between Japan and China on the outskirts of the international zone in 1932, the attacks of July, 1937, led to bloody street-by-street fighting throughout Shanghai in a battle later compared to the epic struggle for the Russian city of Stalingrad.

Somehow, my father had been caught up in all that, although we’d had no word from him.

Both my older siblings had left home - Glen had gone to sea as an officer cadet on a passenger line, and Mary was a nurse in training at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London. However, mother still had to clothe, feed and school Wendy and me.

Wendy and I continued our schooling or, rather, I should say, Wendy carried on learning, while I continued my less than acceptable conduct, ducking school whenever I could.

One afternoon, I ducked off to one of the local cinemas. I can’t remember what the film was that I went to see, but I’ll never forget the newsreel that came before it. In the days before television our only visual source of news, other than the newspapers, was short snippets of documentary footage before the main feature.

As I sat in the mostly empty cinema, dressed in my school uniform, an item came on the screen about Australia. It was about the Royal Easter Show, in Sydney, New South Wales, an annual event when the rural people from all over the State and indeed the whole country came to the city to exhibit their livestock and produce.

Included in the arena entertainments was a ‘Bushman’s Carnival’, what is now known as a rodeo. There was film of bucking horses, bull riding, steer wrestling, camp drafting and other exciting pursuits that the stockmen of Australia indulged in.

I watched, enthralled, as a man with a hat who looked like an American cowboy from the pictures, held on for grim life as the horse he was trying to ride did its level best to catapult him into the air.

‘Hell,’ I whispered to myself, ‘that’s for me.’

I rushed home. I had come up with a plan to save my family from the poorhouse.

I was going to become an Australian stockman.

2

AUSTRALIA, 1938

It was still dark when, shivering under a thin blanket, I roused myself from my bed, an old wool bag strung between two crossed sticks of wood at my head and two at my feet.

Other than where I slept, there was no other furniture in the cold, old shearer’s hut made of rusty corrugated iron. Outside was a bucket of water, with a layer of ice beginning to form on the surface. I plunged my hands in, to wash my face and give my body a quick sluice.

No one had told me Australia would be cold, but here, at Cowra, about 400 kilometres west of Sydney, across the Great Dividing Range, it could get awful chilly in winter.

The moon was going down and the sun not yet up as I finished dressing and walked, feet crunching on frost, towards another day of back-breaking labour.

How the hell had I ended up here?

It had not been easy to convince my mother of the merits of my scheme, that I should emigrate to Australia, aged 13, to save her from the burden of having to feed, clothe and educate me.

It was even harder to get the headmaster and the school’s board of governors to let me out of their sadistic clutches – every child was an earner for them and I was, literally, and figuratively, their favourite whipping boy.

Somehow, perhaps given the fact my father had been captured by the Japanese, feared dead, I wangled it. My mother and I had done our research and had been in touch with the Big Brother Movement, one of a number of dodgy schemes running at the time to ship orphans and children of poor families out to the erstwhile colonies. Supposedly, we would be taken care of by families or kind-hearted Samaritans and enjoy a healthy, well-fed life in the sunshine and open air of the great outback.

The reality was that we were slave labour for farms, or worse.

Some of the unfortunate children dragooned into these schemes suffered physical, emotional and even sexual abuse. Some little boys and girls were lied to, being told by their new masters that they were orphans, so no one would care what happened to them or what was done to them, when in reality they had parents back in the United Kingdom who had been assured their offspring were going to a better place.

At the age of 14 I found myself on a ship, bound for Australia. I was mostly in the company of adults, so growing up fast. Many of the passengers were Australians who’d been visiting the Old Dart and were returning home. I remember sitting on deck with a group of men who had befriended me, all of us talking about our plans for the future and how we might make our fortunes.

‘Don’t worry about money, ever,’ I remember one philosopher saying to me, as our ship approached the port of Fremantle, near Perth, Western Australia. ‘If you ever want it, it’ll be there. Don’t worry about it.’

I don’t know whether this was his optimistic view on life, or if he saw something special or unusual in me, but, as it happened, he was dead right. All my life, whenever I needed it, somewhere, out of the blue, a windfall would arrive. It was nothing ever great, but enough to see me through, and after all, what more does one want?

My arrival in Sydney did not get off to an auspicious start. When our ship docked, there were 11 ‘Big Brothers’ waiting on the docks at Circular Quay, but 12 little brothers on board. All were paired off, except for me.

I would have been alone in a strange country had the local secretary of the Big Brother movement not taken pity on me. She stood in for my absentee Big Brother, doing what was necessary until I was moved on to Scheyville Farm on the outskirts of the city to await ‘distribution’.

Scheyville, under the sponsorship of the Dreadnought Scheme, a similar organisation to Big Brother Movement, trained city boys and immigrants in basic farm work for service on the land. The whole place, a rundown collection of curved corrugated iron Nissen huts, had more of a feel of a Borstal, or juvenile prison, to me. In the past it had, actually, been a prison camp, for interned German civilians and enemy POWs during the First World War, and subsequently served as a drying out tank for alcoholics and deadbeats.

From Scheyville I was palmed off to a sheep and wheat farmer at Cowra. It was there that I was dropped into the punishing, almost medieval routine of life as a ‘wood and water joey’.

Rising before dawn, the air at its coldest, I walked across to the stable to put out the feed, before saddling-up the night pony and going out to the horse paddock to muster up the draft horses, which would be needed for the day’s work on the farm.

Once having shut them in the stable for their morning feed, I left the pony tied up outside while I went over each horse with a dandy brush to knock the sweat off their shoulders from the previous day’s work. That finished, it was off again to get the milk cows into the yard, before going up to the dairy for the buckets and other bits and pieces that attended each days’ milking.

Having milked the six or eight cows, I would let their calves join them before letting them out into their paddock, after which I would take the milk up to the dairy for separating. Having separated the milk, I took the house milk and the cream to the kitchen before taking the skim milk to the pig sties, where I added it to their feed.

Next, I washed down everything concerned with the milking, and chopped wood for the house fire and stacked it in the house ready for use. The ‘water’ part of my job description started with filling two fountains, large tubs with taps on them that stood on the woodstove and provided hot water for the kitchen. After that, I cleaned and scalded the separator and milking utensils and scrubbed out the dairy before going into the kitchen for breakfast.

Finally, it was time to go to work! I would put in a day’s labour on the farm, doing whatever the season required and then at four in the afternoon it was time to start reversing my morning chores. I caught up the night pony to go out and bring the milk cows with their calves in and separate them for the night, before filling the mangers in the stables for the draught horses coming in from their day’s work.

My last job at night, after having had dinner, and just before going to bed, was to let all the draft horses out of the stables and turn them into the horse paddock to graze until I picked them up again at about 4.30 am the next morning.

So my time passed, for five and a half days of the week. On Saturday afternoons I just had to bring the cows in, while on Sundays I did my normal before-breakfast chores, combined with getting the horses in, fed, let out, and their mangers filled ready for Monday morning. Then, the whole weekly cycle was repeated again.

So much for being an ‘Australian stockman’. My princely stipend for all this effort was five shillings a week, plus my keep. Somebody was getting a bargain out of this deal and it sure as hell wasn’t me.

The daytime work on the farm moved with the seasons.

When the harvest was being brought in, it was bloody hard work. My young body ached in the evenings, but started growing muscle from carrying 100-kilogram wheat bags on my back. In all it was tough, thankless, hard and miserable work.

There were some compensations, though. I spent a good deal of time riding horses, which I did bareback, or at least with an empty chaff bag instead of a saddle. I thought this would improve my balance and ‘stickability’, in preparation for my ultimate ambition to be a buck-jump rider. I learned a little bit about sheep, and quickly decided I was not interested in them. It was a pretty rough introduction to rural Australian life, but it helped me develop a sense of independence that I didn’t know I possessed.

On Sundays, after the morning chores were over, I had a weekly bath in an old zinc tub I had found under the tank-stand. I filled it with a couple of kerosene buckets heated over an open fire. Having scrubbed as much dirt off as possible, dried and dressed myself, I then washed my dirty clothes and other odd bits and pieces in the now cold water, and hung them on the fence in front of the hut to dry.

On the odd occasion, if nothing else could be found for me to do, I could sit on the veranda of the hut and just do nothing but enjoy the sunshine. This didn’t happen very often as the old man would use Sunday as an opportunity to walk round the garden, orchard and buildings of the homestead. If he found anything not to his liking, I would be called out to fix it.

Twice in six months, I managed to get a Saturday morning off and hitched a ride into Cowra. My so-called Big Brother, the one who was supposed to collect me off the ship, lived in Cowra, which I understand was the reason I was sent there from Scheyville. However, each time I tried to contact him in the town, he was either busy with a domestic problem, or a business issue. He was a small-time businessman and evidently not a successful one.

Often, I might have been somewhat disenchanted with my work, but I found I loved Australia. I revelled in the eucalyptus smell of the bush, the wildness of the countryside, and being around the animals and the playful, but hard-working sheep and cattle dogs.

While the bloke on the ship had been right, on one hand, that I wouldn’t have to look far for money, I was never going to be very independent on five shillings a week. Money aside, I had not come to Australia to chop wood and feed pigs and draft horses; I had come in search of what I had seen on that newsreel clip in Cambridge, a life as back country stockman and buck-jump rider.

I stuck it for a bit more than half a year, then told my boss I was off.

Still well shy of my 15th birthday, I hopped a train to Sydney and got off at Central Station, in the seedier southern end of the central business district.

With limited finances I found myself a bed in one of the cheaper dives around, the People’s Palace, in Pitt Street, not far from the station. Despite its grand name, this collection of dorms and dank rooms was the flophouse of all flophouses, run by the Salvation Army and catering to the city’s down and out denizens, winos, and hobos.

Fortunately, I’d stayed in touch with the secretary of the Big Brother organisation and she helped me find another job, this time near Moree, in the far north-west of New South Wales, in the Gwydir Valley. It was about twice as far from Sydney as Cowra, but the farmer, Frank, ran sheep and cattle. Where there were cattle, I knew, there would be horses.

Though I was once again taken on as the wood and water joey, Frank was a kindlier soul than my ex-employer at Cowra, plus my duties included a lot of work with his horses. Frank had a club foot and although it didn’t inhibit him in any way from normal riding, he was at a distinct disadvantage in riding the less disciplined of the horses on his property. As a result, he was quite happy to let me take on that chore once he found out that was all I was really interested in.

‘Looks like you’re happier working with horses than doing chores around the house,’ Frank noted one day.

‘You’re right. It’s what I want to really do, work with horses,’ I told him.

After I’d done a couple of months working as the wood and water joey-cum-roustabout, Frank hired another young man from the city. He’d been taken on as a station hand, but it soon became obvious he knew nothing about the bush, let alone the work of a stockman. Frank gave him the duties I was performing and promoted me to station hand.

‘Same money, though,’ he said to me. I would be stuck on seven shillings a week, plus keep.

I couldn’t say no, because I was finally going to get a chance to do what I had set out to do. Frank, being a keen horseman himself, was breeding far more horses on his property than he could ever use in the course of his day-to-day operations on the station, but as he owned the station and it was about his only pleasure, what did it matter if a bit of grass was eaten by horses and not cattle or sheep?

The horses he bred were good, either three-quarter, or seven-eighths thoroughbred with a few true thoroughbred mares amongst the breeding stock as, amongst other things, he was a keen follower of bush race meetings.

Most of the general station stock were what used to be called Walers, named after the state of New South Wales. These hardy horses had already carved themselves a place in history, not only on the wide brown lands of their homeland, but also as mounts for Australian soldiers on the South African veld during the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1901, and in the desert columns that rode triumphant through Egypt and Palestine in the First World War. There were also a few likely looking gallopers in the mob, who would eventually turn up at the local race tracks, and possibly go even further if they turned out to be any good.

I think we made quite a good team, Frank and I. Whenever there was a lull in general station work, or actually any other excuse he could find, Frank was more than happy to ride out with me to the distant paddocks on the station where he ran his horses, and run a suitable mob into the yards he had set up at his outstation, Karaba.

He would then sit on the fence and instruct me in the art of dealing with rough horses. On his better days, one of his favourite pastimes was to select a particularly stroppy looking horse, get me to rope it and pull it up to the fence. Between us, we would saddle it and then I would climb on it and he would let it go.

Off I went, with Frank keeping count of how many bucks I stayed on before being dumped. We would repeat the process until he was happy - either the horse gave in, or I got hurt.

If I had a secret as a horse breaker, it was developing a sense and an understanding of a horse’s temperament from the moment I laid eyes on it, or first touched it. Towards the end of my training period, over the course of about year, I really felt confident that I could run my hand over a line of horses in the race or crush and tell, just by touch and sight, which horse was going to be stroppy and which was going to be easy to break.

With Frank watching, I learned to go about my business with a new horse in the yard. The procedure, if there was no crush, was to put a rope around its neck and choke it down. Once down, an old chaff bag was wrapped over its eyes, the choke rope loosened, and, if I was quick enough, get a front leg tied up.

A halter was then put over its head and the blindfold removed. Once the blindfold was off, the horse would struggle to its feet and hop round the yard a bit with some encouragement from me on the end of the halter shank. As soon as it settled down a bit, I approached it with the old chaff bag, flapping it round until it realised it wasn’t going to get hurt. After that, I rubbed my hand over its face and body and this was generally enough to allow me to let the near-side leg down and go around to repeat the process on the off- side.

I strapped a bridle and saddle into place and the horse was then encouraged to hop around a bit more, which it generally did with a lot more enthusiasm. Once it showed signs of settling down, the offside leg would be freed and I would climb aboard.

The whole process took about an hour, and if all went well, the horse could be ridden out of the yard, wheeled around the paddock, then steered back into the yard where I dismounted, stripped the gear off, and declared the horse broken.

By today’s standards my methods may sound barbarous, but one must remember times were different then. Horses were the mainstay in operating those large stations; there were plenty of them and, most of all, they were cheap.

Horses today are something special, out of the ordinary and generally for people with money. They’re bred for the track, or shows, or as pampered mounts of the landed gentry. Back in the 1930s a horse was a beast of burden, a working animal, like a dog.

Then, a horse was the alternative to a farm implement or a machine. Unlike today, where a foal comes into contact with its owner the moment it arrives, the horses on Frank’s property, and others, were born out in the paddock or the bush and left to run wild with their mothers until they matured. Their only contact with humans would be when they were branded and, where necessary, castrated – a brief, painful and unpleasant experience.

Frank was a very good horseman and was willing to spend endless time patiently passing his skills and knowledge on to me. In a year or so I evolved into quite a competent back-country horse-breaker. It is incredible how quickly one can pick up the techniques, if not the experience, if one is passionate about something.

Frank must have thought so as well. ‘You should start going around and breaking in horses for people on some of the other stations around here, if you like,’ he said to me.

I saved the wages I received from Frank and with his encouragement and a small loan to top me up, I invested in a couple of horses of my own, some tack and some camping gear and set myself up as a contract horse breaker.

I moved from station to station, wherever work was available. I had no doubt Frank was recommending me to the other property owners in the region, as I certainly had plenty of work.