9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

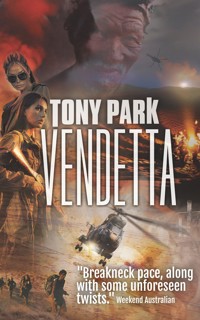

Captain Sannie van Rensburg and safari guide Mia Greenaway are caught in the crossfires of a decades-old feud between five veterans of South Africa's apartheid-era Border War.

Haunted by the deadly mission that shaped their lives forever, the ex-paratroopers must finally confront their demons, and each other, at the funeral of a comrade in the red dunes of the Kalahari Desert.

But their scars run deep, and as the truth emerges, each man must ask himself: When serving your country, what makes you a hero and what secrets are worth killing for?

"Vendetta has Park's trademark setting, and breakneck pace, along with some unforeseen twists that will keep you guessing until the final pages." Weekend Australian

"Highly recommended," Army News, Australia

"Filled with suspense, betray and revenge, this novel will have you guessing right until the very end – in true Tony Park style." Australian Arts Review.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

VENDETTA

TONY PARK

CONTENTS

About the Author

Also by Tony Park

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

If you enjoyed this book…

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

TonyPark was born in 1964 and grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney. He has worked as a newspaper reporter, a press secretary, a PR consultant and a freelance writer. He also served 34 years in the Australian Army Reserve, including six months as a public affairs officer in Afghanistan in 2002. He and his wife, Nicola, divide their time equally between Australia and southern Africa. He is the author of twenty other African novels and several biographies.

www.tonypark.net

First published 2023 in Macmillan by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd

This edition published by Ingwe Publishing 2023

Copyright © Tony Park 2023

All rights reserved

www.ingwepublishing.com

The moral right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity (including Google, Amazon or similar organisations), in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Vendetta

EPUB: 978-1-922825-10-0

POD: 978-1-922825-11-7

Cover design by Leandra Wicks

Cover image of walking soldiers © Al J. Venter

ALSO BY TONY PARK

Far Horizon

Zambezi

African Sky

Safari

Silent Predator

Ivory

The Delta

African Dawn

Dark Heart

The Prey

The Hunter

An Empty Coast

Red Earth

The Cull

Captive

Scent of Fear

Ghosts of the Past

Last Survivor

Blood Trail

The Pride

Part of the Pride, with Kevin Richardson

War Dogs, with Shane Bryant

The Grey Man, with John Curtis

Courage Under Fire, with Daniel Keighran VC

No One Left Behind, with Keith Payne VC

Bwana, There’s a Body in the Bath! with Peter Whitehead

Rhino War, with Major General (Ret) Johan Jooste

For Nicola

PROLOGUE

HAZYVIEW, MPUMALANGA, 2012

The book of the dead. That’s what Frank Greenaway called the old photograph album he was hunting for in the mildew-smelling reaches of the top cupboard of his second-hand wardrobe.

Frank’s fingers found it, and as he dragged it out from under a mouldy suitcase he felt the clear plastic dust cover start to crackle and disintegrate under his touch. The catalogue of memories, good and bad, had lain there, undisturbed, for more years than some of the men in it had been alive; longer still since the dates of their deaths.

He swayed on the small stepladder. Frank felt dizzy, weak. He was babalaas, but when was he not hungover? This, though, was a bad one. Perhaps it was the DTs, delirium tremens, from having been in the Hazyview police cells for the best part of the previous two days. He didn’t know the symptoms – he couldn’t remember how long it had been since he’d gone thirty-six hours without a drink.

Slowly, he navigated his way down and retraced his tracks, sticky spots of blood on the floor tiles, from the bedroom to The lounge. He usually went barefoot around town, in the same uniform of rugby shorts and T-shirt that he wore this warm September day. He told anyone in the pub who would listen how he could walk the length of the Kruger without shoes, but he was human. Just. He was bleeding from whatever piece of rubbish he’d trodden on in his unkempt front yard.

Frank sat at the cane and glass dining table – someone’s castoff, though he couldn’t remember whose. Mia smiled down at him from the school portrait on the wall. She had her mother’s eyes. Frank sniffed. He opened the album, then reached for the half-jack of Klipdrift brandy and poured himself a tot.

‘Frik.’ He raised his glass to the first of the fallen, the twenty-year-old grinning under the weight of the radio on his back and flashing a peace sign. Frank drank.

The edges of the album pages were stained brown with the same nicotine that had dyed his fingers and coated the grimy ceiling fan above him. Outside, Mrs Baloyi’s Africanus dog barked incessantly and a cape dove mocked him with its call. Work harder, work harder. He hadn’t had a proper job since the bloody parks board had fired him.

Frank took his eyes off the photos to fossick in the ashtray for a stompie with a little life left in it. He found one, lit the cigarette butt and coughed through the burned, stubbed-out end.

Mia would have loved to have got her hands on this album. She asked him about the army often, and he could hear the amateur psych in her questions, wanting to know how he felt, did he have flashbacks, did he want to talk about the war? He was a Parabat, and ’Bats didn’t get PTS-bloody-D. The war hadn’t fucked him up, bloody people had.

He didn’t talk; he drank. Smoke curled upwards as Frank turned the pages, tracking his time through basics, infantry training, learning to jump out of aeroplanes, then perfecting the business of killing, in Angola. He found the photo he was looking for. Ondangwa, 1987 was written in faded pencil on the back. He stared at Evan, Ferri, Adam, himself and the trackers. The others were smiling.

After all these years of hardening himself, medicating with the booze, trying and failing to get on with life, the memories broke free. They pushed out from his brain and his soul, through his skin, oozing out of his pores and into the judgmental daylight. He started to cry.

How many times had he sat at this table, planning how to take his own life? It was usually moments like this one, when he knew Mia was away on some school camp or visiting a friend, so that she would not be the first to find his body.

That had been his answer, his one certain way to escape the memories, the shame, the failures of his life. Frank turned another page. There he was in his dress uniform, sergeant’s stripes freshly sewn on, ramrod-straight. Dead eyes. Lost a war, lost a wife, lost a job.

Frank blinked. He felt nauseous, weak, like a bad flu was coming on. He coughed again; looked at his watch. Midday on a perfect Lowveld day. As good a time as any to put an end to twenty-five years of hurt.

Nokuthula Mathebula alighted from the minibus taxi at the fourway stop, where the Zimbabwean man sold his metal warthogs and the tiny tin San hunters, who crouched with their bows and arrows. She tutted at the tourist trinkets and shook her head. Nokuthula hadn’t seen a Bushman, as the San used to be called, in her entire life.

She checked her phone. It was two o’clock, but Frank was not a stickler for punctuality. She walked slowly, not wanting to perspire into her new blouse. Sometimes Frank didn’t know what day it was. Her heart was heavy for him, but it would be good to see Mia again.

Nokuthula had known Mia since the day she was born, and had carried her on her back, wrapped up like a Shangaan baby, and taught her the language and the ways of her people. When Mia’s mother had died, the little girl had become like one of her own.

They had all cried when Frank had told them, some years earlier, that he had lost his job in the Kruger Park, and that he could no longer afford to employ Nokuthula fulltime. Now Mia was nearing the end of her schooling, a beautiful, smart, independent young woman, but Nokuthula still secretly thought of her as her baby. Nokuthula looked forward to seeing Mia on the infrequent occasions when Frank had enough money from whatever casual job he had found to pay for her to clean the house.

As Nokuthula walked up the street, with its face brick and tile single-storey homes set behind walls topped with razor wire, she saw Mrs Eva Baloyi, Frank’s neighbour, standing outside his security gate.

‘Inhlikanhi, Eva,’ Nokuthula said.

‘Ayeh minjani.’

‘Phukile,’ Nokuthula replied. She was ‘awake’ and well this afternoon, happy at the thought of seeing her daughter when Mia returned from the school camp tomorrow. The plan was for Nokuthula to stay the night in her old room, the domestic’s quarters.

Mrs Baloyi was wide-eyed. ‘Ndzi swi twile gunshot.’

‘What?’ Nokuthula recoiled a pace. ‘You heard a gun firing? In Frank’s place?’

‘Yes.’

Nokuthula scrabbled in her big handbag for the gate remote. She pressed it hard and Mrs Baloyi followed her in and across the overgrown lawn. She fumbled with the keys until she found the one for the front door, then burst inside.

Nokuthula screamed.

1

KWAZULU-NATAL, THE PRESENT

He must be the town drunk,’ the teenage girl said, her voice low but audible from the open window of the Porsche Cayenne.

Adam Kruger pretended not to have heard her. Stereotypes – his country was still fixated with them. He saw himself through her eyes – why else would a middle-aged white man be working in a car park? The boy behind the wheel was not much older than the girl, maybe first year varsity, here on the coast south of Durban for the holidays. The number plate was GP – Gauteng Province, Gangster’s Paradise; vaalies, tourists. Stereotypes. As he reversed from the low-rise open-air Scottburgh Mall parking spot the driver reached a gym-fit, tattooed arm out the window and handed Adam a two-rand coin.

‘Baie dankie,’ Adam said, touching the tip of his faded Toyota baseball cap. He started to direct the young man out of the car space, but the youngster floored the accelerator. The girl screeched with joy; an older Indian couple stepped back to avoid being hit. Adam remembered himself at that age, showing off to girls, wearing a tank top to display his Parabat ink, his paratrooper’s wings. Stupid. The girl’s words cut him, partly because there was a grain of truth in them. He was not an alcoholic – even though he might have been one at some points in his adult life – but it was true that the money he made as a car guard at Scottburgh Mall went on the meagre booze ration he allowed himself these days.

Sweat trickled down his body under the second-hand long sleeve shirt and reflective vest that read ‘Car Guard’. The shirt was fraying at the collar, but the creases in the sleeves were ironed to a knife’s edge. The jeans were hot in this weather, but like the shirt they kept the sun off him. Rassie Erasmus, the medic who Adam had fought alongside in the war, had survived Angola, two marriages and a proper battle with the bottle, then passed from melanoma five years ago.

Adam heard a horn hoot and turned, narrowing his eyes as he slipped the single coin into his zippered imitation leather bum bag. Porsche boy had not got far; he was stopped behind a white Fortuner. There was a young man behind the wheel of the Toyota, which was parked in the middle of the road, blocking the exit. The youths in the Cayenne yelled abuse.

The Fortuner driver was alert, checking the rear-view mirror, not checking his phone. Why had he stopped? Adam felt the hairs come to attention on the back of his neck. He looked to the mall entrance. A security guard in body armour had his back against a wall, an LM5 assault rifle held at the ready; he’d chosen a good position but his attention, like most of the people in the car park, had been diverted by the road-rage incident currently unfolding fifty metres away from where Adam was standing. A cash-in-transit van was parked in the disabled spot near the entrance to the mall; two guards were walking out with boxes full of money.

Adam looked around. He saw four young men striding between the cars. Like him, their clothes were wrong for the beach and the weather. One opened his jacket and Adam saw the glint of sun on steel, a short-barrelled AK-47.

‘Gun!’

Adam had the attention of the security guard; he pointed at the advancing men. All of them had now drawn weapons: two had rifles, two pistols.

The guard raised his weapon but was too slow. The first round from the AK thudded into his body armour. The man was slammed back into the wall, winded, his eyes wide with surprise – maybe that he was still alive. Gasping and clearly in pain, he tried to raise his rifle again, but the second round hit him in the neck.

Adam bent low and ran between the parked cars as shoppers screamed and fled. The Porsche was reversing. One of the armed bandits fired at it. The others opened up on the cash-in-transit guards, who dropped their cashboxes and were fumbling for side-arms.

Adam was unarmed, but he moved towards the robbers anyway. There was a thud and the screech of metal on metal as one car backed into another. The Fortuner was still blocking the way out, and the line of holiday shoppers that had been circling the car park looking for convenient spaces near the mall was gridlocked as panicked people tried and failed to get away from the shootout. The two guards who’d been inside the mall were firing back. By calling out a warning, Adam had forced the hijackers to show their hands much earlier than they would have liked. One was advancing; the way he walked tall, rifle up and firing, made Adam wonder if he was jacked up on drugs. Maybe he’d purchased umuthi from a sangoma to make him bulletproof. A slug from one of the guards’ guns punched him backwards.

‘Adam!’ a voice hissed.

Adam, still ducking and moving, glanced over the bonnet of a Ford Ranger and saw Wilfred, a Zimbabwean parking attendant, keeping pace with him.

‘Go back, take cover,’ Adam said.

Wilfred shook his head. ‘No. This is our duty.’

Madness, more like it, thought Adam, but he felt the adrenaline, all but absent in this second half of his time on earth. It powered him up, making him forget this life, taking him back to another.

He smelled the cordite, heard the percolator pop of an AK on full auto. Another windscreen shattered; people were screaming.

Adam heard his own pulse, then the report of a pistol being fired from further away in the car park. A bullet punched a hole in the door of a Polo right in front of him. The shot had come from the flank. Adam raised his head and saw a shopper, a man going grey, like himself, aiming a nine-mil. The robber with the AK swung and fired a burst on full automatic and the vigilante dropped to his belly.

Adam looked around for a weapon and saw a broken paver on the edge of a garden bed. He picked it up. The thieves’ momentum had slowed and Adam heard a siren. The man with the AK turned his attention back to the guards and emptied his magazine at them. One of the security men cried out in pain and this prompted the remaining two criminals to resume their advance.

The rifleman fumbled while replacing his magazine and Adam closed in on him from behind.

One of the man’s comrades called a warning as Adam rose fully upright; he knew he only had a second or two in which to act. The gunman spun around and raised his AK-47. Adam noted that while the fresh magazine was now fitted, he hadn’t seen the man pull back the rifle’s cocking handle. The robber pulled the trigger; nothing happened. Adam drove into him, knocking the rifle barrel to one side, and smashed the broken paver into his face. The man’s head snapped back. Adam was on him, unleashing his rage; he dropped the broken piece of cement and punched the man in the face. Wilfred joined him and Adam took the rifle from the dazed and wounded man’s hands. Wilfred held the man down while Adam cocked the AK with practised ease.

The feel of the wooden handgrip and stock; the weight of the rifle; the heat from the barrel; the smell of oil – all threatened to overwhelm his senses. The muscle memory brought the weapon up into his shoulder and he almost craved the kick of the recoil as he searched for a target.

The thief who had called the warning turned, moving between an Amarok and a Land Cruiser Prado, and his gun hand tracked towards Adam.

‘Drop it!’ Adam leaned over the bonnet of the Polo, lowering his profile, making himself a smaller target as he took a sight picture. The young man grinned and pulled the trigger. Adam saw the boy’s hand buck, heard the crack-thump of the nine-millimetre projectile cleave the air next to him, then squeezed the trigger himself. Adam’s bullet hit the target in the shoulder, knocking him backwards.

Adam ran to the downed man. He had dropped his pistol when he was hit, and was now trying to roll over to get to it. Adam bent down, picked up the pistol and stuffed it in the waistband of his jeans.

The last of the thieves sprinted for the Fortuner that had been blocking the car park exit in the instant the attack went down. As Adam had suspected, this was the getaway vehicle.

Adam tracked the fleeing man through the AK’s sights, but he was not about to shoot him in the back. As the robber opened the rear door of the Fortuner the driver put his foot down, forcing the bandit to run faster, holding on to the handle. He managed to hop, skip and drag himself into the back as the Toyota reached the mall entry. A battered South African Police Service bakkie rolled into the car park, heading the wrong way up the one-way access road, and the two vehicles collided, head-on.

Steam hissed from the two punctured radiators and the driver of the Fortuner was struggling to get out from behind his airbag as the police exited their vehicle, guns drawn. The two men in the getaway car surrendered.

Two other car guards emerged from where they had taken cover behind vehicles and ran to Adam, who was now on his feet. ‘Watch this one with the bullet hole in his shoulder. Find something to stop the bleeding,’ Adam said to them.

Adam ran to the wounded security guard. He was being treated by one of the cash-in-transit guards, but Adam immediately saw that the man holding his hand to the other’s neck was also wounded. His face was grey and as Adam arrived, the first responder slumped back against the wall.

Blood spurted from the other man’s neck in a straight jet, staining the white-painted concrete. Adam ripped off his shirt, popping the buttons, and balled up it and his vest, pressing the makeshift dressing against the man’s neck. A stream of blood hit him in the face and chest as he fought to find purchase and stem the bleeding. The third guard was on his phone.

‘Ambulance on the way. Do you know what you’re doing?’ he said to Adam.

‘His carotid’s severed.’ Adam pressed down harder on the wound, shifting his fingers so that he could push the severed artery against the bones of the man’s spine, slowing the flow. Rassie had taught them that move. The spurting stopped.

The guard who was questioning him was now tending to his other comrade, who had been shot in the shoulder. Adam saw that the other casualty had gone into shock, but the wound looked like a through-and-through. He would live. The driver of the cash-in-transit van emerged from the armoured vehicle with a first aid kit, then stood over all of them, pump-action shotgun in hand.

The man in Adam’s arms came to. ‘I . . . I am alive,’ he croaked.

‘Yes, bru,’ Adam said. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Themba.’

Adam held him, keeping his hand on the man’s neck. ‘You’re going to be fine, Themba. Hang in there, man.’ Adam was not at all sure of his words but he said them as confidently as he could. ‘Help is coming for you; you’ll be in hospital just now.’

People were drifting back to the mall and the scene of the shootings, curious now that the gunfire had stopped. Adam glanced up and saw that the girl from the Porsche was videoing him.

‘Check out this guy’s abs,’ she said to the tattooed boy next to her, ‘the old dude’s ripped.’

Adam shook his head, concentrating on the man in his arms. He closed his eyes, tight, but not enough to force away the image of Frik Rossouw, who had died in the dust in Angola from a gunshot wound to the head.

He heard the thwap of rotor blades. Now I really am crazy.

The noise grew louder, but Adam couldn’t turn to face it because if he moved, he might relax the pressure on the wounded guard’s artery. A hail of grit sandblasted his bare torso as a real-life helicopter touched down in the now half-empty car park.

‘It’s one of our car-tracker choppers, from our company,’ the van driver yelled over the whine of the engine.

The other guard performing first aid finished tying a dressing around the man with the shoulder wound, then came to Adam. ‘Come, let’s get Themba to the chopper. He needs to get to a hospital as soon as possible. He’s lost too much blood already.’

Adam felt light-headed. Maybe it was the heat, or the sounds of the gunfire and the chopper. He felt like he was floating, hovering in the air, watching himself and the other man half walk, half carry Themba to the little Robinson helicopter.

‘You need to go with him, to Ondangwa,’ Adam said. ‘Hold your hand against his neck like I’m doing.’

‘Huh? Isn’t Ondangwa in Namibia?’ the man asked. Adam shook his head. ‘I mean Durban, to the hospital.’

The pilot was out of the chopper and had the rear door open. The three of them managed to slide Themba onto the seat. Adam took the guard’s hand and placed it over his, holding his shirt, then slid his hand out. Blood spurted as the man relaxed the pressure when climbing into the chopper. Adam showed him again and they managed to staunch the flow once more.

‘Go!’ Adam said.

The pilot needed no further encouragement. Within seconds she was strapped in and the helicopter lifted off. The guard in the back, still holding his hand pressed firmly against Themba’s neck, caught Adam’s eye and gave him a nod.

Adam turned away from the rotor downwash and when the chopper was gone, he walked to the planter where he’d stashed his backpack and a bottle of water that Pinkie, one of the checkout ladies from Food Lovers’ Market, kept in the deep freeze for him. It had all but melted in the heat. He sat down heavily and tipped cold water over his head, running a hand through his bristly salt and pepper crewcut. The guard’s blood, mixed with Adam’s sweat, ran in rivulets over his skin.

An ambulance arrived and the paramedics on board began triaging the wounded robbers and security guard. Wilfred was keeping watch on the man Adam had smashed with the broken paver. He was sitting up, holding a hand to his head.

A shadow fell over Adam and he looked up. It was the boy with the tattooed arm and the loudmouth girl from the Porsche.

‘That was hectic, man,’ the boy said. ‘You were like Chuck Norris on steroids, dude.’

Adam blinked and stood. He clenched his fists to stop them trembling. He was returning to earth from his out-of-body experience, but now that the adrenaline and rage were leaving his body he felt the crippling tiredness taking hold of him.

‘We thought you were, like, just a car guard,’ the girl said. She looked him up and down, appraising him anew, and twirled her hair in the fingers of one hand.

At nearly two metres in height and broad across the shoulders, Adam towered over them. The boy took an involuntary pace backwards. His eyes were drawn to the parachute wings tattooed on Adam’s bicep.

‘Were you, like, a Parabat, in the parachute battalion or something?’ the boy asked; he held his phone towards Adam.

Adam raised a hand to try to obscure the tiny lens. He glanced around the car park. The area was now swarming with police, armed response security officers and emergency services personnel. If they needed him, they would find him.

‘I’m just a car guard.’ He turned and walked away.

2

Captain Susan van Rensburg, known to most as Sannie, had been in the Galleria shopping mall in Amanzimtoti, looking at bikinis in the Rip Curl shop when her phone had rung with a message about the robbery and shootings at Scottburgh. She had left the store immediately and driven 35 kilometres south on the N2 to Scottburgh Mall.

Although senior to her in rank, Gita was younger than Sannie by a few years and, as on every one of the few occasions Sannie had met her, looked as if she had just stepped out of a day spa. Not a strand of her straight black hair was out of place and her makeup accentuated her eyes, which Sannie thought were one of her best features.

‘Sannie, howzit, sorry to disturb you on your day off,’ Gita said before excusing herself with a smile from her media interview.

In contrast to Gita, who wore a crisp white linen suit and a silk blouse, Sannie was dressed in denim shorts, a white V-neck T-shirt and imitation Birkenstocks. Her Z88 service pistol was clipped to her belt in a holster and her South African Police Service ID hung on a chain around her neck.

‘No problem.’ Sannie took her sunglasses from the top of her head and put them on; she was still getting used to how bright the light seemed in KwaZulu-Natal, as well as the coastal climate. The Kruger National Park, in Mpumalanga, where she had last been based as head of the Stock Theft and Endangered Species Unit, had been very hot in summer, but KZN elevated heat, and humidity, to a whole new level. Not for the first time she wondered if she had made the right decision, applying for a transfer and uprooting her life. Sannie looked around the car park. ‘Well, this is a mess.’

‘Sannie, I know you’re still settling in, and house-hunting, but I already know from my own sources that you’re an exceptional detective.’ Gita nodded to the television crew, a cameraman and a young woman with an elaborate hairdo, who were packing up their gear. ‘My gut tells me this is going to be a big media story, so I want someone clever interviewing the guy who neutralised two of the robbers. Half a dozen witnesses have already been talking about this “superman” who saved the day.’

‘Was he one of the cash-in-transit guards?’ Police crime scene investigators were photographing the van, whose thick armoured glass windows were starred from gunshots; another technician was taking pictures of a bloodstained wall. Small flags with numbers were placed in several locations, indicating spent bullet casings. ‘This looks like a moer of a shootout.’

‘Not exactly. A parking attendant, would you believe it?’ Sannie raised her eyebrows. ‘Some poor Nigerian or Zimbabwean earned their five rands’ worth today.’

‘He’s a white guy, Sannie. One of the eyewitnesses said the man had a military tattoo, parachute wings. He took out one of the robbers by klapping him with a broken paver, grabbed the guy’s AK and shot and wounded one of the others. He also saved the life of one of the security guards, who was shot in the neck; the man made it to hospital in a chopper and he’s listed as serious but stable.’

‘Impressive, but this could get political,’ Sannie said.

Gita nodded. ‘That’s why I was right to call you in today. The story’s already breaking on social media and it will be on TV tonight and in the newspapers tomorrow. Even for South Africa it’s incredible – car guard saves the day. Check out the I’m going nowhere Facebook group.’

Sannie took out her phone and opened the Facebook app. The page was popular, with a couple of hundred thousand followers – proud South Africans who were bucking the trend of the many who had emigrated from South Africa to countries such as Australia, New Zealand and the United States. The site would never normally post a video of an armed robbery, but this was a criminal event with a twist – a citizen had saved the day.

Sannie heard the distinctive sound of an AK-47 firing on full auto through the phone’s speaker. There was no vision of a robber being shot, but an excited young man was giving a running commentary.

‘Hectic; this car guard dude picks up the guy’s AK and foils the robbery, then the cops ram the getaway car.’

The video of the car guard was grainy and jerky. Sannie paused it a couple of times. She saw the man, maybe early fifties, with short grey hair. A later snippet showed him shirtless, giving first aid to a fallen security guard. The next clip showed the man’s face, briefly, but then he put his hand up, as if covering his identity.

‘I’m just a car guard,’ he said, in response to a question about whether he had been in one of the army’s parachute battalions.

‘Modest,’ Sannie said to Gita as she closed the app. ‘Have we got a name for him?’

‘Adam Kruger. Mall management has the names of all the car guards, but there’s no address listed for Kruger – not unusual, as some of the guards are homeless. The uniforms found a till operator from Food Lovers’ who said she thinks he stays somewhere south of Scottburgh. I need you to find him, quickly, Sannie. The girl says Kruger does not have a car, and he left straight after the attempted robbery. He dropped off the pistol he took from one of the tsotsis with a security guard before he fled the scene. I've got a couple of bakkies out looking for him, but no one’s found him yet.’

‘I'll need to talk to the supermarket worker,’ Sannie said.

Gita looked around. A female officer was talking to a younger woman by the entrance to the mall. ‘That’s her.’

‘Thanks.’ Sannie strode over and thanked the uniformed officer. ‘I'll take it from here,’ she said, turning to the other young woman. ‘Hello, how are you? I’m Captain Susan van Rensburg. I’d like to talk to you about Adam Kruger. What’s your name?’ Sannie took her notebook and pen from the back pocket of her shorts.

‘I’m Pinkie Ndlovu, but I've already told the other police everything I know about Adam.’

‘Yes, I understand, but I may have just a few more questions for you.’

The young woman looked at her watch. ‘I need to get back on shift, but all right.’

‘Does he wear a wedding ring?’

Pinkie looked taken aback. She hadn’t been asked that question. ‘Um, no. I told the other officer that he doesn’t talk about himself.’

‘You’re friends with him, though?’

She shrugged. ‘He is quiet, but he is a good man.’

‘Why do you say that?’ Sannie made a note.

‘He helped me, once. There were some guys, not local, in the car park one day when I was coming off shift in the evening. They were drinking beer and brandy, whistling at me, saying some suggestive things. One of them touched me, and I screamed. Adam came and sorted them out.’

‘“Sorted them out”? How many of them were there?’

‘Four.’

‘What did he do to them?’

Pinkie looked around, not wanting to make eye contact. ‘I don’t want to make trouble for him. Those guys never came back.’

Four to one. ‘Is he a violent man?’

Pinkie shook her head. ‘No, another time, some different guys were taunting him, calling him trash and names like that. People think . . . Well, some people say that as well as the poor people and those without jobs, that sometimes people work as car guards to get money for drugs or beers. Adam is never drunk. Even when those guys insulted him, he just stood there, saying nothing.’

‘You told the other officer that Adam does not have a car. Does he come by taxi? Does he walk?’

‘He runs.’

It was Sannie’s turn to be surprised. ‘In this heat?’

‘Every day that he works here.’

Sannie made a note. ‘He doesn’t come here every day?’

Pinkie shook her head. ‘No. Maybe three or four days a week, then I might not see him for another week, then he comes again. But I see him in the afternoon or evening, when he finishes. He goes to the bathroom in the mall and he comes out in his running gear, with his day clothes in a small backpack.’

‘Does he run to work?’

‘He runs to Scottburgh Beach.’ Pinkie pointed towards the coast. The beach was only a couple of kilometres from the mall, which was on the R102, the coastal road, set back from the town. ‘I saw him on my day off once, by the caravan park; he showered there and got changed, then walked to the mall. When he finishes work, he runs to wherever he lives.’

‘Do you know where that is?’

She shook her head again. ‘I asked him once and he said, “south”, that was all. One time I wanted to know how far he ran and he said, “about twelve kilometres”.’

Sannie made a note and pictured where that would be. ‘Pennington?’

Pinkie just shrugged.

‘Did you talk to him, the day you saw him at Scottburgh, after he had changed?’

‘Yes, I did,’ Pinkie said. ‘I asked him if he had been swimming. He said no, not there, but that he liked to swim at Rocky Bay. Will he get in trouble, for shooting that man?’

‘I don’t know,’ Sannie said. ‘But it’s important I talk to him.’

‘People are saying that he told the robber to put down his gun, and that the man fired at Adam. It was self-defence,’ Pinkie said.

‘We’ll see.’ Sannie put her notebook away.

Gita was busy talking to a man with a notebook and pen – probably another reporter. Sannie went to her Fortuner, got in and started the engine. The air conditioner provided some much-needed relief.

She turned on her sat nav and used her fingers to examine a map of the coast. She was getting to know this part of South Africa, mostly through her house-hunting. The Hawks’ regional office was in Port Shepstone, about sixty-five kilometres to the south of Scottburgh. Sannie was staying in a flatlet above the garage of her brother-in-law Johan’s house in Pennington, twelve kilometres in the same direction; Rocky Bay, where Kruger liked to swim, was between where she was now and her temporary home.

It was hellishly hot and he had just shot a man. If he wanted to get away, for whatever reason, he might head for the sea. Sannie checked her watch; by her reckoning it had been forty-five minutes since the brief but bloody firefight had gone down.

This Adam Kruger was a man with no car, who was fit and ran to work. Sannie would find him.

Northern Cape, South Africa

The black-maned lion, beautifully silhouetted against the red sands of the Kalahari Desert, gave a low, rumbling call. The big cat was so close to head guide Mia Greenaway and her guests that it felt like the aluminium body panels of the Land Rover were vibrating from the noise.

Digital cameras clicked and beeped, but the lion wasn’t bothered.

‘He’s sending a warning to another male,’ Mia said softly, ‘to let him know that this is his territory, and not to enter.’

Here in this vast inland ocean of sand Mia still felt, sometimes, like an outsider, as though she was on someone else’s turf. She had grown up in South Africa’s Lowveld, on the edge of the Kruger National Park. Her natural habitat was the thickly vegetated banks of the Sabie River, where one was more likely to encounter a prowling leopard than one of the resident lion prides. It wasn’t only the landscape that was different, it was also the culture. Mia was fluent in Xitsonga, thanks to Nokuthula Mathebula, the Shangaan carer who had raised her after her own mother passed, and she had left her best friend, tracker and mentor Bongani Ngobeni behind in order to further her career. Occasionally she wondered if she’d made the right choice. Also back ‘home’ in Khaya Ngala Lodge in the Sabi Sand Game Reserve was her on-again, off-again, now former boyfriend, Graham Foster. Handsome and too alpha for his own good, Graham could drive her mad for different reasons. She had told herself, when the opportunity came up to transfer to Dune Lodge, that she needed a change of scenery for many reasons, and the Kalahari had certainly delivered that.

‘What would happen if the other guy came onto this one’s turf?’ Joe, one of her four American clients asked. They were two couples: a pair of dentists – Bill and Judy – and a pair of doctors – Joe and Melanie – from Michigan.

‘There’d be a big fight,’ Mia said, ‘probably to the death.’

‘Say, if Luiz isn’t well I could always take a look at him,’ Melanie said.

‘Thanks, Melanie,’ Mia said. ‘That’s really kind of you, especially as you’re on holiday, but I’m sure the lodge manager will get him to the local doctor in Askham if he’s quite ill.’

Luiz Siboa was Mia’s San tracker and Mia had made up a story about him not feeling well to cover the fact that he had not reported for work prior to the early-morning game drive at Dune Lodge. Mia was worried but was trying not to show it. In all the time she’d been at the lodge, Luiz had never missed a scheduled drive. There had been no sign of him in his room in the staff quarters, either, when Mia had checked in the pre-dawn darkness as she readied for the morning safari.

They watched the lion for a few minutes more, listening to him call. After the big cat had padded across the sand to sit down in the shade of a lone thorn tree, the Canons and the Nikons ceased fire.

‘Are we all good?’ Mia asked, running a hand through her short dark hair.

‘Sure thing.’ Bill had a habit of speaking for the group. Mia did a quick scan of faces and they all nodded. They’d stayed out a little later than normal; it was nearly eleven am and Mia knew that as keen as the Americans would be, they would be getting hungry and starting to cook themselves in the open-topped vehicle.

She started her engine and radioed camp to let them know that they were fifteen minutes out. The manager, Shirley Hennessy, would make sure there was a staff member waiting with cold towels and an icy mocktail, or chilled champagne, to welcome the guests back to the lodge.

The guests were buoyed after the lion sighting, which had been the highlight of their morning. It was as though the unspoken pressure on Mia to deliver amazing game sightings had been lifted and the group could relax.

‘So,’ Joe said, leaning forward in his seat so Mia could hear him over the engine noise as she drove through a patch of thick sand, ‘how long have you been at Dune Lodge?’

‘Three months.’ Mia changed gear. ‘I was working as head guide at Julianne Clyde-Smith’s other lodge, Khaya Ngala, for the last couple of years.’

‘That’s where we’re headed next,’ Melanie chimed in.

‘You’ll love it,’ Mia said. ‘The Sabi Sand Game Reserve, where Khaya Ngala’s located, is very different from the Kalahari. Lots of thick bush and big trees – good leopard country, but you won’t see big black-maned lions the size of the guy we just had.’

‘But no pangolins or aardvarks, right?’ said Judy, with a note of triumphalism.

‘Let’s just say that in my five years at Khaya Ngala I saw pangolin five times and aardvark maybe nine or ten – here in the desert, we drive past the aardvarks to get to the pangolin.’ It was true – Mia had found the sightings of these two safari bucket list creatures amazingly plentiful on the equally surprisingly chilly nights at her new lodge.

‘Why did you move here, Mia?’ Joe asked as they bounced along the undulating road.

‘Julianne encourages movement between her lodges for professional development, not just here in South Africa, but also part-time exchanges with staff from properties in Zimbabwe and Tanzania. I've got a master tracker’s qualification, but the San people, like Luiz, take tracking to a whole new level and I wanted to improve my knowledge and skills. I've learned so much here.’ There was also another reason Julianne had wanted Mia to move to Dune Lodge, but that was commercial-in-confidence and her guests didn’t need to know.

‘Are the San, like, the Bushmen of the Kalahari?’ Judy asked.

They passed a magnificent male gemsbok, better known to the tourists as oryx, but whereas the striking grey antelope with its black-and-white face and long, pointed horns had been a fascinating photographic subject for the tourists on their first day, now Mia knew better than to stop. ‘That’s their old name, which isn’t used anymore,’ Mia said. ‘It’s considered disrespectful.’

‘What kind of a name is Luiz, for a San man?’ Melanie asked. Where to start? Mia glanced over her shoulder. ‘It’s Portuguese.’ Bill raised his eyebrows. ‘He’s from Portugal?’

‘No, Angola, originally. That was once a Portuguese colony. Luiz was born there – sometime in the mid-to late 1950s – he told me once he’s not a hundred per cent sure of his age, but he thinks he’s sixty-six. In his younger years he lived a totally traditional life as a San hunter-gatherer in the bush. When he was about seventeen, he joined the Portuguese army to fight against the forces trying to liberate Angola during the 1960s and early seventies.’

‘Against his own people?’ Judy said.

Mia knew she’d opened a can of worms, but the guests were asking questions, which meant they were engaged, and that meant they were happy. ‘Not really. The San have been marginalised throughout their history. They were the original inhabitants of much of southern Africa, but migration by more numerous African tribes started to displace them from their hunting grounds, and the arrival of colonial armies and settlers just made things worse. They were enemies of some of the other tribes.’

‘So they fought on the side of the whites, the Portuguese?’ Joe said.

Mia nodded. ‘Yes. Luiz’s family were pro-Portuguese. I’m not exactly sure of his family’s history – he’s a very reserved guy – but I do know he had a stepsister who was half-Portuguese. She was the mother of Shirley, our lodge manager, who is Luiz’s niece.’

‘OK,’ said Melanie. ‘I was wondering about Shirley’s surname, Hennessy. I've got distant cousins with the same name, and they’re Irish Americans. Is she married?’

‘No,’ Mia said. ‘I don’t know the ins and outs of her family, but Shirley did tell me once that her late father actually was an Irishman living in South Africa. Anyway, when Portugal pulled out of all its African and other colonies after a coup in Lisbon in the 1970s, the white South African army took on Luiz and hundreds of other San soldiers and employed them in their fight against the new Angolan government, and against other nationalists, fighting for independence in Namibia.’

‘Boy, Africa is complicated, with all these different tribes and so forth,’ Bill said.

Mia held her tongue. So too was the American Civil War, she wanted to say.

‘What was this war over?’ Judy asked.

Mia took a deep breath. ‘In South Africa we called it the Border War. In the seventies and eighties the apartheid-era government was under threat from within, with the rise of Nelson Mandela’s ANC – the African National Congress. Angola provided a safe haven for the ANC, and for an organisation called SWAPO, the South West Africa People’s Organisation.’

‘South West Africa was the old name for Namibia, right?’ Bill interjected.

‘Exactly, Bill,’ Mia said. ‘And their military wing, PLAN, the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia, was launching raids across the border into what we know as Namibia, which back then was considered almost part of South Africa. The South African government was fiercely anti-communist and they were concerned about the election of a left-wing government in Angola, which was backed by Cuba and Russia. The South African Defence Force waged war in Angola, propping up a guy called Jonas Savimbi and his party, UNITA.’

‘And Uncle Sam played a role,’ Bill said. ‘The CIA was backing Savimbi and I read a novel that said Savimbi financed his war effort with elephant ivory, rhino horn and blood diamonds that the US and South Africa helped him sell abroad.’

‘Correct again, Bill, on all counts. White South African men, including my father, were conscripted to fight and sent to the border with Angola. There were some big battles inside Angola, and fighting in South West Africa. It all ended in a kind of draw in 1990 when Namibia was proclaimed as an independent country.’

‘How did someone like Luiz end up here,’ Melanie asked, ‘so far from home and his traditional life?’

Mia liked Melanie. She was compassionate and caring, which Mia guessed made her a good doctor. ‘At the end of the war in Angola, Luiz and hundreds of San soldiers and their families were moved to South Africa, to a military base near the diamond mining town of Kimberley; they would have been persecuted if they’d tried to return to Angola. Nelson Mandela granted them land and a permanent home close by, in a township called Platfontein, when he took power in South Africa.’

‘That was good of him,’ Melanie said.

Mia didn’t want to disagree, but she’d learned, through Luiz and Shirley that life was hard for the San refugees from the war.

‘Sure,’ Mia said. ‘But they ended up in basic housing in an arid area far from their homelands, with nowhere to hunt and very few prospects for jobs. After the democratic elections here in South Africa, many people still saw them as enemies.’

Melanie nodded. ‘I see. I’d love to talk to Luiz, when he’s feeling better; or, like I say, if there’s anything I can do . . .’

‘Thank you, Melanie,’ Mia said, meaning it.

Mia returned her eyes to the road, but caught sight of a dark speck in the sky in her peripheral vision. She slowed and looked up.

‘Vultures,’ she said, seeing that there was more than one, coming in to land.

‘Where?’ Bill asked.

‘Ten o’clock high, buddy,’ Joe said. ‘You need some new glasses.’

Mia drove to the crest of the next dune to get a better look at what the vultures were interested in. She stopped and took out her Swarovski binoculars, a tip from some other clients from the United States; Americans could be incredibly generous and appreciative guests. She knew this spot well; the big camel thorn tree standing stark and picturesque against the sparse desert view was a favourite shady spot for Mia and the other guides to break their game drives for morning coffee or afternoon sundowners. She focused, then bit her lower lip.

‘Um, everyone, just sit still in the vehicle here for me. I’m going to take a look.’

‘Will you be safe?’ Judy asked.

‘For sure, just stay in the Land Rover.’ Mia took the long, green canvas bag from the racks on the Land Rover’s dashboard and unzipped it. She pulled out her .375 Brno rifle, got out of the vehicle, opened the bolt and loaded her weapon with five fat slugs from the hand-tooled leather cartridge belt around her waist. ‘Back in a minute, please sit tight.’

‘OK. You be careful, now,’ Melanie said.

Mia nodded and walked away from the game viewer. The red sand was loose, and she felt each step in her calves, but the thudding in her chest worried her more. She looked around. For kilometre after kilometre the desert stretched away like an empty sea of red waves. It was the nothingness she’d found hard to get used to, at first. She had longed to see the towering leadwood and jackalberry trees that lined even the dry watercourses of her homeland, let alone the flowing Sabie River, but in time she had come to appreciate the desolation. It made the impressive camel thorn she was heading towards an even more special landmark. Here, in the middle of nowhere where the reserve was situated, nearly one hundred kilometres from the nearest town, Askham, she felt a peace she hadn’t known since before the death of her father. What she hadn’t told her guests was that her dad, Frank, had killed himself, and that she was sure the war she’d spoken of, like a history teacher, had been part of the reason why he’d done it. The silence, at first eerie, almost scary, now calmed her.

A vulture took flight as she came closer and others hopped away from the carcass they were feasting on, close to the base of the tree. She could hear the thwap-thwap of massive wings cleaving the air as others hauled themselves skyward.

The sun overhead stung the back of her neck; perspiration beaded her upper lip. She gripped the rifle tighter, her palms slick. The lion the big male had been challenging could be close, in the lee of the next sandhill, resting in between eating. She did not think, however, that a lion, cheetah, or one of the secretive Kalahari leopards had made this kill.

Mia looked at the sand. Tracking in this place was maddeningly difficult; she tried to remember everything that Luiz had told and shown her in the last three months. Mia glanced over her shoulder. Her tourists were sitting still, at least, the two men watching her through binoculars.

She brought the butt of the Brno into her shoulder, ready, just in case. A movement to her right startled her, and she swung the barrel around. It was just another vulture, a late departure.

Her Rogue boots squeaked beneath her and she felt grains of sand being kicked up onto the backs of her legs. The kill was no more than twenty metres away now and she could confirm that her first instinct had been right.

Again, she scanned around her, 360 degrees, searching for danger. When she looked back to the place where the vultures had been, she saw the blood, and on the hot desert breeze, she smelled the first telltale odours of death. Mia closed her eyes, but a tear forced its way out and rolled down her cheek.

‘No,’ she whispered.

She stopped and saw what the vultures had begun feasting on. She didn’t need to go closer to confirm it was a human, a man dressed in the khaki shirt and green shorts of Dune Lodge.

Luiz.

3

From Scottburgh, Sannie took the R102 and headed south. The old main road meandered along the country’s eastern coastline, all the way to Cape Town on the southern tip of the continent. The Indian Ocean sparkled on her left.

She kept her eyes peeled for men jogging along the road but saw no one. Running in this heat would be murder; never had she been so grateful for the Fortuner’s air conditioning.

After Park Rynie she took the turnoff on the left to Rocky Bay and crossed the railway line. Passenger services had been discontinued on the line some years earlier, she had learned, and freight trains ran infrequently – and not at all since the huge floods that had ravaged the province. At Pennington she’d seen people walking and running along the line, hopping from sleeper to sleeper – maybe Adam Kruger had taken this route.

She could be wrong about her theory that Kruger had walked or run here, but as a detective she’d learned long ago to follow her instincts. As always, she was keeping an open mind about this case, but she was hoping she would be able to wrap it up quickly.

She’d only been in her new job for three weeks and now she was due to go on leave the following week. She was looking forward to the break to visit her good friend Mia Greenaway, though the Kalahari Desert and the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park would be just as hot as the south coast, if not more so.

Sannie nosed the Fortuner into a spot in the municipal car park overlooking the ocean. To her right was the rocky promontory that gave the bay its name, topped with a short concrete walkway with safety railings, perfect for fishermen. Two anglers had lines in the water. In front of her an older couple, maybe from the caravan park on the other side of the parking area, lay in the shade of a beach umbrella, reading. A family was sitting down to a picnic meal under a fold-out gazebo; three teenage boys laughed in the surf as waves broke over them.

Sannie got out and pulled her sunglasses down. To her left was the ski boat club, a rather small, two-storey brick building with a kitchen downstairs and a bar with a wooden deck above. She could see a couple sitting at wooden picnic tables upstairs.

She crossed the car park and went to the club. Inside, she took the stairs.

‘Morning, can I help?’ asked the blonde bartender who was wiping the counter. A heavy-set grey-haired man with a red face, a quart bottle of Castle Lite in a cooler in front of him, nodded hello.

‘Just looking for a friend,’ Sannie said.

‘Who?’ the bartender asked. ‘Chances are I'll know him or her.’

‘Adam Kruger.’

The older man at the bar burped. ‘Sharky.’

‘Sorry?’ Sannie said.

The bartender set down her cloth and put her hands on her hips. Her eyes went to the pistol on Sannie’s hip – her shirt had ridden up, exposing the handgrip. ‘What do you want with Adam?’

Sannie took out her police ID, held it outstretched for the bartender to see, then hung the lanyard around her neck.

‘Here.’ Sannie turned at the sound of a male voice and the blonde woman looked over Sannie’s shoulder. A man’s head and shoulders appeared through an open window; he was shirtless and had been sitting at one of the outside picnic tables, though she hadn’t seen him from the car park. The face disappeared.

As Sannie walked onto the wooden deck, which was just wide enough to accommodate the table-and-bench combos, the couple who had been outside passed her and headed downstairs.

‘Adam Kruger?’

He looked her way and gave a small nod. He had short hair, dark speckled with grey, and was deeply tanned. His torso was virtually hairless, and his abdominal muscles were clearly etched, though she doubted he was the kind to wax or pay for a gym membership. Like the old guy propping up the bar inside, Kruger was also drinking from a quart – Black Label, this time. The cheapest beer in the bar.

As she walked to him, she noticed his eyes. They were the most striking shade of green, and even though he was looking at her it felt like she was invisible to him, like he was looking through her to some far horizon. Maybe he was drunk already, but in his body language she detected no sign of relaxation or inebriation; if anything, he seemed hypervigilant. He sat in the far corner, which is why she hadn’t seen him; his back was to the wall, the ocean to his left.

‘I’m Captain Susan van Rensburg, from the Hawks. I need to talk to you about the events at Scottburgh Mall this morning.’

He took a swig of beer out of the bottle. ‘How did you find me?’

‘It’s my job.’

He nodded, twice, slowly. ‘You’re good at it.’

She stood there, her right hand resting on the pistol grip of the Z88. ‘Why did you flee the scene of the robbery and shooting?’

‘I didn’t flee. My shift was over.’ He glanced away, back to the Indian Ocean. ‘And I don’t like crowds.’

‘Yet you work in a shopping mall car park. Month-end must be a bitch.’

He glanced back at her. ‘I need the money.’

Sannie nodded to the half-full bottle he’d just set down. ‘For that?’

Adam shrugged. ‘As it happens, yes.’

He was being flippant, or insolent, or maybe both. ‘I need to take a statement from you and decide whether or not to charge you. We can do it here, or I'll put the cuffs on you and take you to Port Shepstone.’

‘Can I buy you a drink?’ he asked.

‘No.’ Sannie sat down on the picnic table seat opposite him and took out her notebook. She asked him his full name and date of birth. He was fifty-five, twelve years older than her. She would have put him at mid-forties. If he was a drunk, working in a car park to buy cheap beers, he kept himself in good shape. ‘Occupation?’

‘Parking attendant.’

‘No other job?’ she asked.

He shrugged. ‘I do some odd jobs here and there. In the peak tourist season I get work on the dive boats if someone else calls in ill.’

‘Address?’

He gave the number of a house in Botha Place, in Pennington. It was immediately recognisable to her, although she still did not know the village well. ‘Is it for sale?’

‘Not anymore.’

‘Ah.’ She nodded.

‘You in the market?’ He finished his beer and set it down on the table.