9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Ex-mercenary Sonja Kurtz is out for revenge after her daughter Emma is assaulted by an abalone poacher while on a beachside holiday near Cape Town.

When the poacher is murdered, Sonja is targeted by a violent local gangster and must flee the country.

As Sonja leaves a trail of destruction in her wake – from the threatened wilderness of Zimbabwe to the treacherous beaches of northern Mozambique – a concerned Emma must find the courage to rescue her mother.

But is Sonja a cold-blooded killer? Or is there a darker conspiracy taking place in southern Africa’s underworld – one that will change their lives forever?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tony Park was born in 1964 and grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney. He has worked as a newspaper reporter, a press secretary, a PR consultant and a freelance writer. He also served 34 years in the Australian Army Reserve, including six months as a public affairs officer in Afghanistan in 2002. He and his wife, Nicola, divide their time equally between Australia and southern Africa. He is the author of nineteen other African novels and several non-fiction biographies.

www.tonypark.net

ALSO BY TONY PARK

Far Horizon

Zambezi

African Sky

Safari

Silent Predator

Ivory

The Delta

African Dawn

Dark Heart

The Prey

The Hunter

An Empty Coast

Red Earth

The Cull

Captive

Scent of Fear

Ghosts of the Past

Last Survivor

Blood Trail

Part of the Pride, with Kevin Richardson

War Dogs, with Shane Bryant

The Grey Man, with John Curtis

Courage Under Fire, with Daniel Keighran VC

No One Left Behind, with Keith Payne VC

Bwana, There’s a Body in the Bath, with Peter Whitehead

Rhino War, with Major General (ret) Johan Jooste

For Nicola

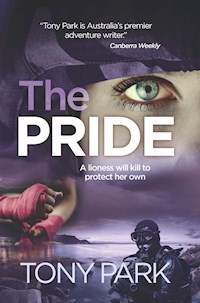

THE PRIDE

TONY PARK

LNGWE PUBLISHING

First published 2022 in Macmillan by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd

This edition published by Ingwe Publishing 2022

Copyright © Tony Park 2022

All rights reserved

www.ingwepublishing.com

The moral right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity (including Google, Amazon or similar organisations), in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The Pride.

EPUB: 978-1-922825-04-9

POD: 978-1-922825-05-6

Cover design by Paris Giannakis

For Nicola

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

1

Sonja Kurtz waded onto the beach and tossed two seashells on the sand. She savoured the warmth of the sun on her skin as she slid off her dive mask and wrung the sea water from her ponytail.

The Indian Ocean was cool enough to raise goosebumps here, close to where it mixed with the Atlantic off Africa’s southern tip. She bent, slowly, to retrieve her spoils and examined them. Dressed in a cream bikini, diving knife and weight belt hugging her waist, she walked across the squeaky-fine sand. And fell over.

‘Mum!’

Sonja creaked her way back to her feet, brushed the sand from her legs and belly with her free hand and threw the shells at Emma with the other. ‘Fucking knee.’

‘You’re a little old to be impersonating a Bond Girl, with the knife and all.’ Emma put a hand to her mouth, not quite managing to hide her smile as she put down her book and looked over the top of her sunglasses. ‘You should get that knee seen to.’

‘Ja, and my back, and my rotator cuff, and my neck.’ She flopped down on her towel, next to Emma. ‘Do you at least like the shells?’

Emma picked one up. ‘You should take these back to where you found them. People don’t collect seashells any more. It’s not woke.’

‘What’s woke?’

Emma shook her head. ‘You’ve been in the trenches too long.’

Sonja looked up and down the beach, surveying the terrain out of habit. She’d set them up on high ground, in the dunes at the quiet end of six-hundred-plus metres of sand so white she had to put her sunglasses on to cut through the glare. The Blesberg, a steep sand hill fringed with vegetation, rose steeply to their right, protecting the flank of their commanding position.

It was early and there were not yet enough people around to make her feel uncomfortable. All the same, she registered them – the very handsome young man in white briefs, oiled and gelled; the Joburg family, red-skinned and noisy; a young woman, milk-white skin and long black hair hanging beneath a floppy sunhat – another European swallow in Cape Town for the northern winter; the silver fox, faded tattoos, who looked at Sonja, again. A gull hovered over them, squawking, looking for food. The woman in the hat looked their way for a moment and Sonja caught a glimpse of mirrored glasses. Stop being paranoid, Sonja told herself. Threat status, low.

Sonja glanced at Emma, who had picked up her book again. ‘You used to love seashells when you were a little girl.’

‘Yes, but I didn’t know any better. They’re part of the natural habitat and now you’ve gone and disturbed it.’

Sonja patted the diving knife against her thigh. ‘You weren’t complaining when I told you I was going to get us a nice fat kreef for lunch.’

‘A what?’

‘Crayfish.’

‘Oh, well, that’s OK. They’re not on the green list, and just so long as you don’t get a female. If you go back in the water, check it’s not a female, with eggs under the tail.’

Sonja saluted. ‘Jawohl!’

‘Don’t pretend you’re some sort of dinosaur.’

‘I’m not quite that old, though not far off it.’ Sonja put her knees together, checking for swelling on the right one. The left one bore a long, vertical scar from the reconstructive surgery; starboard side would be next.

‘And stop talking about how old you are,’ Emma ordered. ‘You’re making me feel old.’

‘You started it. Stop telling me off,’ Sonja said. She tried to make it sound light; she did not want to spoil this. She hadn’t seen her daughter since before the pandemic and even then she hadn’t been on a holiday, either alone or with Emma, for years. Less work, and more time alone while Hudson was working in Zimbabwe, fed her underlying guilt.

Leaning back on her elbows, the paperback she’d brought virginal and unopened beside her on the towel, she went back to scanning the beach, trying to think like a holiday-maker. The knife on her belt was not just about fishing; she liked South Africa and America because she could carry a weapon and not feel like she was overly crazy. On the rare occasions she did go out unarmed she caught herself time and time again reaching for her missing pistol.

Sonja’s phone beeped. She picked it up and saw it was a WhatsApp message from Andrew Miles, a former military pilot she knew. Mozambique is kicking off. I’m flying in some reinforcements for Oosthuizen next week. He wants to know if you’re in?

Below the message was a link, which Sonja clicked on. It was a News24 report.

Mercenaries are being flown by helicopter to the besieged Mozambican coastal town of Palma to evacuate civilian employees of a large liquefied natural gas plant following attacks by armed insurgents with links to the Islamic State group.

She chewed her lower lip. Her thumb hovered over the phone’s screen as she debated her answer.

‘Anything interesting?’ Emma asked.

Sonja looked up; there was the damn guilt again. ‘No, just a friend.’

‘You don’t have any friends.’

Sonja poked her tongue out and Emma went back to her book.

She read more. A Mozambican army base had been overrun, the lightly manned garrison taken unawares, the article said, and two hundred AK-47s and machine guns and a score of RPG-7s – rocket-propelled grenade launchers – had been stolen. Cabo Delgado province, where Palma was located, was home to palm-fringed white-sand beaches and old Indian Ocean slave trading ports which now acted as import–export hubs for heroin from Afghanistan, methamphetamine from China, and ivory, rhino horn and abalone from Africa.

There was a video embedded in the report. An ageing Alouette helicopter came in to land, and armed men jumped off even before the wheels touched ground. They ran to a group of civilians who were carrying backpacks or suitcases. Sonja thought she recognised Steve Oosthuizen, carrying an AK-47. Despite Emma’s jibe Oosthuizen was, actually, a friend about her age, and happily married, last she’d heard. He was ex–32 Battalion, one of the old South African Defence Force’s ‘terrible ones’ from the war in Angola, like Hudson Brand, her on-again, off-again long-term partner. Sonja had worked with Steve as a private military contractor in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Sonja went back to her messages. Tell Steve thanks, but no thanks. I’m retire . . . She deleted the last word and tapped on holiday instead, then hit send. Retired sounded too old, and she did not need to abandon her daughter in search of yet another foreign war. All the same, watching the chopper come in had given her a flutter in her belly.

If you change your mind, you know where to find me, Miles messaged back.

She returned to the news link. A second report had caught her eye; it was an article from the UK, foreshadowing a return to serious sectarian violence in Northern Ireland. When she looked up from her phone she saw that Emma was staring at something, or, rather, someone.

Two young men, late teens or early twenties, fighting age, appeared in Sonja’s peripheral vision, traipsing up the path through the dunes from the car park behind them. Smooth brown skin, wetsuits rolled down low below their hips to show off washboard abs, they each carried fins, a regulator, a diving cylinder, a mask and BCD – a buoyancy control device vest. One of them elbowed the other, nodded towards Sonja and Emma and whistled.

Emma frowned and went back to her book.

‘I think he likes you,’ Sonja said.

‘I’m getting too fat. It’s the skinny Milf he likes.’

‘Hah!’ Sonja’s phone rang. She checked the screen; it was Hudson Brand. She accepted the call. ‘Howzit?’

‘Fine. How you doing? I saw from Emma’s Instagram that you’re back at Silver Sands. Weather looks good.’

‘Ja, fine. It’s beautiful here.’ Sonja had mostly picked the Airbnb at Silver Sands on Betty’s Bay because it looked quiet and remote, an hour and a half’s drive from Cape Town. She avoided crowds. ‘I won’t ask what you’re doing stalking young women on social media. How’s Zimbabwe?’

‘Hot,’ he said. ‘Oh, and some of the guys from the charity that maintains the waterholes in the national park stumbled on a mobile drilling rig and some Chinese miners today.’

‘Serious?’

‘Yup. Shit’s hitting the fan up here, and rightly so. The miners claim they have government permission to be in the park, but the Zimbabwe parks and wildlife guys know nothing about it.’

Beside her, Emma sat up straight, put her book to one side and shielded her eyes. ‘The men in the water have both got bags, and look, the one on the right has a piece of metal, like a tyre iron. Big knives, as well.’

‘Standby,’ Sonja said into the phone. She looked at Emma. ‘So?’

Emma lowered her voice. ‘They’re hunting abalone, I’m sure of it.’

‘So?’ Sonja asked again.

‘So, they’re responsible for the destruction of one of South Africa’s natural treasures. They’re poachers, Mum.’

Sonja and Emma had visited an African penguin colony the day before, at the old whaling station at the other end of Silver Sands Beach; Sonja had made a conscious effort to do something fun and touristy, but Emma had met and struck up a conversation with an older guy, an academic who lived locally and knew all about abalone poaching. Now Emma was an instant expert on endangered sea creatures, and poaching had once again intruded into Sonja’s life.

It was annoyingly interesting, Sonja thought, because she had just been reading about abalone being smuggled out of Africa via Mozambique. The scale of the illegal trade in wildlife – animal products, shellfish, even plants – was depressing. Sonja had not come to the beach to think about wars or poaching, but here they were, once more, trying to drag her in.

Emma stood. ‘They use scuba tanks these days because the abalone’s been cleared out close to shore and they have to dive deeper for it. Bloody disgusting.’

‘Emma . . .’

‘What’s that about poachers?’ Hudson said, on the phone.

‘I’ll call you back,’ Sonja said.

‘Love you,’ Hudson said.

‘Same. Whatever; got to go.’ She ended the call. She did love him, and was letting her defences down with Hudson more and more, but that scared her, sometimes. There were things she needed to discuss with him, secrets to share about her past that no one alive knew, and the thought terrified her. For now, she had a daughter to worry about. Emma had started walking towards the water. ‘Where are you going?’

Emma looked back over her shoulder and Sonja saw her own face, twenty or more years earlier, all blue eyes, auburn hair and sneer.

‘I’m going to get some pics of them and SMS them to the marine anti-poaching hotline.’

‘Emma!’ Sonja recalled that the guy Emma had befriended when visiting the penguins was part of a volunteer poaching monitoring organisation.

The phone rang. It was Hudson again; she hit the decline button and struggled to her feet.

‘Hey!’ One of the men was knee-deep in the water, suiting up, and had seen Emma holding her phone up. ‘Wat doen jy?’

‘Emma, come back,’ Sonja said, but as she got closer to the water where Emma stood, checking the pictures she had just taken, Sonja could make out what the men were saying to each other in Afrikaans. Emma would not have understood, but one of the men had just said: ‘That cunt won’t be a problem, when I get finished with her.’

Emma held up her phone again, in video mode this time, and addressed the camera. ‘These men are abalone poachers and they’re obviously heading out to those rocks,’ she pointed to a low, dark-coloured island, ‘called the “bait bar”, a place where abalone still grow.’

Sonja marched across the sand and grabbed Emma from behind, by the upper arm. ‘Turn the camera off.’

‘Ow. Let go, you’re hurting.’ Emma shrugged off her mother’s grip.

Sonja released her, but kept an eye on the men. The one who had threatened Emma glared at her. ‘Go back and sit down,’ Sonja said quietly.

Emma cupped her hands either side of her mouth. ‘I know what you’re doing!’ she shouted.

The foul-mouthed man shrugged off his BCD and began wading through the water towards them.

‘What are you going to do, big man?’ Emma said, hands on hips.

‘Emma . . .’ Even as she said her daughter’s name once more, going through the motions of trying to calm things down, Sonja felt her pulse rate slow and the adrenaline tap open. She saw the plan unfolding in her mind as the boy approached them. Every single pre-conceived thing this cocky young buck thought was weak about her was working to Sonja’s advantage.

‘You can’t take my fucking picture,’ he said in English.

Emma stood her ground, continuing to film as the young man left the water and closed in on her.

He was both tall and solid. He lunged for Emma, ignoring Sonja, who had positioned herself on his right, as if she were stepping back from the action. The moment the man’s hand touched her daughter’s, Sonja struck.

Her right fist popped, like a forty-millimetre grenade leaving its launcher, and smacked into the man’s temple. He folded into the sand.

Sonja fell on him, one knee on his neck, and directed another jab into his nose for good measure. He howled, but still tried to reach his right hand down towards his leg. Sonja had long ago seen the dive knife strapped to his calf and was already on it. She slid the blade from its sheath and pricked her victim’s hand with the point, making him gurgle and yelp again.

‘Hey!’

Sonja and Emma looked from the squirming cockroach to the other wetsuited man who now emerged from the water. Unlike his friend, this one had his hands up.

‘I’m sorry,’ the man called. ‘We didn’t mean any trouble, ma’am.’

‘You should have told this one to behave before he came at my daughter.’

‘We were just going for a dive is all. I apologise if he offended you.’

Sonja held the knife up and pointed it at him. ‘You or your friend come near my daughter and I’ll gut you, understood?’

The man nodded. ‘Denzel, come. Let him go, please, ma’am. I’ll take him away.’ He looked Emma in the eye. ‘I’m sorry.’

Denzel was flailing at Sonja’s leg so she eased the pressure off his neck.

‘Need any help here?’

Sonja glanced around and saw that the Silver Fox had come over to them. Others on the beach were also staring; the woman with the floppy hat stood, hands on hips as she watched them, but came no closer.

‘I think I’ve got the situation in hand,’ Sonja said.

The grey-haired man held up a phone. ‘Want me to call the police?’

Sonja looked to the standing man.

‘We were just leaving,’ he said.

Sonja stood. Denzel punched a fist into the sand to help himself stand and swore under his breath. His friend grabbed him by the arm and drew him away. Denzel pointed his forefinger at Sonja, pantomiming a pistol.

‘Fokof, seuntjie,’ Sonja said.

Denzel was shrugging his friend’s hand off him as the two of them went to the water’s edge and picked up their dive gear. Instead of leaving the beach, though, they quickly suited up and waded into the water, disappearing below the shimmering blue surface.

Sonja went back to their towels and gathered their things, stuffing them into a beach bag. She noticed that more onlookers had appeared from the beach car park, a line of them looking down at them. She felt the first prickling of panic, not as a result of the fight but because she now felt hemmed in, caged.

‘Let’s go,’ Sonja called to Emma.

Emma held up her phone again, as if to take another video. Sonja hurried over, snatched it out of her hand and strode off.

‘Give that back!’

Sonja ignored her as she trudged through the dunes.

‘Those men are responsible for the destruction of precious marine life, Mum.’

‘Come on.’

‘But, bloody hell, I thought you were going to kill that guy, the way you were kneeling on his neck, like that poor man in America.’

Sonja stared at her daughter. The youth had come at her, full of anger and arrogance, and now she was talking about human rights? Sonja walked on, the anger boiling up inside her. She’d come on this holiday to reconnect with her daughter, but Emma talked like she was from another world. Her daughter thought poaching could be stopped by posting a video on social media; Sonja had gone into the bush hunting rhino poachers and her husband, Sam, had been killed filming a documentary about the plight of the animals. The gulf between her and Emma seemed to widen all the time.

‘Mum?’

She walked on, knowing that if she spoke it would make things worse. Her phone rang again and she snatched it out of the beach bag as her feet squeaked angrily on the sand. It was Hudson. She dropped the phone back into the bag where it continued to ring and vibrate, taunting her, reminding her there was a man a few thousand kilometres away who would ask her, again, if she was all right, and tell her, again, that he loved her and wanted to be with her. If he meant it, why was he there, in Zimbabwe, when he knew that she split her time between America and South Africa?

Sonja ignored the looks from people in the car park, even the impromptu applause from a couple of young men as she transferred the beach bag to her left hand and shook out her right, trying to ease the pain in her knuckles. She pushed the button on the remote to unlock the rental car, got in, started the engine and turned the air con up to full blast. She felt like she was overheating. She craved a cigarette, even though it had been years. She had to acknowledge that for all her anger and disquiet, there had also been the rush, as she took charge and took the boy down, and as much as she hated to admit it, there had been the thrill.

Looking up into the rear-view mirror she saw crow’s feet and emptiness.

‘Get a grip,’ she said to the woman in the reflection. ‘You’re on holiday.’

2

Emma Kurtz lay on her bed in the house where she and Sonja were staying, golden late-afternoon sun streaming into her room. Her phone buzzed.

Hey kiddo, how’s things?

The message was from Hudson Brand. Although Hudson was away working in Zimbabwe, managing a safari lodge in Hwange National Park, as far as Emma knew he and her mother were still an item.

OK.

That bad? How’s Mom?

Hudson was an American – well, half; his mother had been of Portuguese and Angolan descent – so like South Africans he said ‘mom’ instead of ‘mum’, something that Emma, who had grown up in England, could never get her mouth around.

Emma chewed her lip. Three double Klipdrift and Coke Zeros for lunch.

What happened on the beach today?

As well as being a safari guide, Hudson was a part-time private investigator, and very little got past him. He was not her father, but Emma knew Hudson cared for her, and probably loved her like a daughter. She didn’t want to alarm him. No biggie, just some guys acting like jerks. Mum sorted it.

With a gun?

She laughed out loud, adding an LOL for effect. Can you talk?

Her phone rang before she had time to dial.

‘You OK, really?’ he asked.

‘Um, yeah.’

‘Once more, with feeling,’ Hudson said. ‘Want to tell me about it?’

Unlike with her mother, Emma felt as though she could pretty much tell Hudson anything, such as if she was having trouble with Sonja, or with boys, or even with her work as a battlefield archaeologist. He knew how to read people, possibly because of his time as an investigator. He’d also been with the CIA when he was younger. Emma explained what had happened with the two young men on the beach.

‘She hit him in the temple?’

‘Yeah.’

‘The guy’s lucky to be alive, the way your mom throws a roundhouse.’

‘Straight jab.’

‘Then doubly lucky. How’s she doing otherwise?’

Emma sighed. ‘Usual. Short temper, jumpy, doesn’t like crowds, either moves at full speed ahead or dead slow, like now. She’s sleeping. I was hoping we could just have a normal holiday, like regular people, and maybe reconnect. It was going OK – we saw penguins and a couple of days ago we drove to the V&A in Cape Town and went dress shopping.’

‘Sonja? Dress shopping?’

‘I know, right?’ Emma tried to smile, but squeezed her fingers to her eyes. ‘I just feel like now we’ve gone backwards again.’

‘PTSD’s a bitch, Emma.’

‘What can I do?’ Emma asked. She knew that Hudson had been to war, in Angola, when he was younger.

‘Keep her active, doing stuff that’s healthy and a positive distraction. The problem is that if she spends too much time indoors, alone, drinking, she’ll keep going over and over all the stuff in her head. And trust me, there’s plenty of it.’

Emma knew Hudson’s last remark wasn’t meant to hurt her, but she felt it. ‘I try to get her to talk, but she clams up.’

‘Yeah.’ Hudson paused. ‘I hear you. Talking’s good if it’s done a safe way, but it can also trigger too many bad memories. She’s trying to protect herself, and you, Emma.’

‘I guess. But I’m twenty-seven now, for God’s sake.’

‘No one’s saying you’re a kid.’

No, Emma thought, but she did feel like Hudson and Sonja were part of a club that she wasn’t entitled to join. It was frustrating.

‘I know it’s hard, believe me,’ Hudson said. ‘Your mom knows all about PTSD and I’ve heard her, seen her, talking to people she knows who are suffering. She just can’t deal with it herself. Give her time, Emma.’

Emma looked out her window. Betty’s Bay was dappled with golden light. There was a line of people walking along the beach. She wanted to ask, ‘How long?’ but knew there was no point. ‘Thanks, Hudson.’

‘I know it’s not much help, but I’m here, any time you want to talk.’

‘Thanks.’

‘Bye, Emma.’

She ended the call.

Emma felt restless. She scrolled through Instagram, but when she saw a picture of her ex, Alex Bahler, who was posed on a ski slope in Canada with a blonde with big lips by his side, she slammed the phone face down on the bedside table. Jumping up, she changed out of her denim skirt and T-shirt into running clothes and laced up her trainers. She put her phone in an armband, pulled it on and then activated her wireless headphones.

Her rubber soles squeaked on the polished floorboards in the corridor. The houses at Silver Sands, nestled in the stunted but thick zone of coastal fynbos behind the beach, were a mix of old seventies holiday homes and more contemporary designs, like the grey steel and glass place Sonja had found.

Emma knocked on Sonja’s bedroom door. ‘Mum?’

When there was no answer, she scrawled a note on the pad fixed to the refrigerator with a magnet and left it on the kitchen counter, telling her mother she had gone for a run and would be back in half an hour. Emma figured Hudson’s advice about staying fit and active applied to her as much as to Sonja.

It was cool outside; the weather here could change by the minute and grey clouds were amassing above the rocky Kogelberg mountains that rose steeply back from the narrow stretch of coastline. Emma thought she had enough time to run a couple of lengths of the beach before the rain came.

She did some quick stretches then set off. Her time in lockdown in the UK had not been good for her. Exercise had been restricted, but she hadn’t made the most of the periods when it was available, and she’d drunk and eaten too much. She had not been on a dig for over a year, either, and had missed even the exercise that the hard, physical side of her life as an archaeologist demanded. She’d been productive, though, doing some post-graduate study remotely, and Sonja had covered her loss of earnings when the consultancy Emma had been working for inevitably laid her off.

A woman walking a dog smiled and nodded to her as she followed Watsonia Road, which ran parallel to the beachfront. A cute guy, also running, nodded to her and she flashed him a quick, if somewhat pained, grin. She was breathing hard already.

The salt air felt raw and clean and she told herself again how good it was to get out of Glasgow for a while. Unlike Sonja she had not been born in Africa, but she could not deny that the continent had hooked its thorny barbs into her.

Emma tried not to replay the scene on the beach that morning as she ran past the spot where they had been happily sunbathing, but the memory of the man, Denzel, coming towards her, and the touch of his hand on hers came back unbidden. She ran harder, trying to blot out the image, the feelings.

She had been full of bravado on the beach, trying to film even after the attack, but now, with time to think about it, she felt anxiety rise up in her chest like heartburn.

Emma had thought that the two boys would back down, or be scared by the threat of her catching them on camera. Instead, Denzel had come at her, his face growing larger on the screen with every pace, so that she need not have zoomed in. Emma had been in danger before in her life, but this time the young man had been armed with nothing but his bare hands and the single-minded intent to do her harm. He hadn’t even bothered drawing his knife, so sure was he that he was taking on two helpless females.

Well, one.

Sonja’s unleashed violence, devastatingly quick, momentarily merciless, but ultimately controlled, had scared her almost as much as Denzel had.

Emma had never romanticised her mother’s calling as a soldier or, later in life, as a private military contractor – a modern-day euphemism for a mercenary. Half-remembered platitudes, such as ‘Mummy protects people from baddies’, didn’t cut it when you were a four-year-old wetting the bed at Grandma’s house, or a spotty-faced teenager being bullied at boarding school.

Emma was the first to admit she had been a handful as a teenager, a situation not helped by the fact that Sonja’s then partner had tried to groom her for sex, but beyond the normal teen angst she knew she was suffering from the years Sonja had spent away from her. As a single mother Sonja had done well, materially, putting Emma through private school and university, and she was still comfortably off. Life, however, was about far more than bank balances.

They’d led separate lives in recent years – perhaps all their lives – but lately Emma had found herself wanting to reach out and connect with her mother, possibly because it was becoming clear to those very few people who were close to Sonja that she was not doing well.

Emma looked out to the sandhills and saw a procession of people emerging. The line of beachgoers she had seen on the sands earlier had moved on, but as she continued to jog, closing the gap, she saw that these were not retirees or holiday-makers out for a late-afternoon stroll on the beach. These people were on a mission, on their way to work.

She could see men, mostly young, but a few with grey hair, wearing wetsuits and either carrying or wearing diving cylinders. Interspersed with them were younger men and boys, and a few women and girls, all carrying backpacks or bags slung over their shoulders. Some were also carrying spare cylinders, presumably for the men who would go underwater. In all there were about thirty people and when Emma came to the car park, she saw half a dozen vehicles, mostly old and rusty. She recalled the academic telling her that this was a drop-off place for poachers, but she was surprised that the criminals were so blatant; it was as though they were walking to work and there was no one about to try to stop them. Emma knew the problem of illegal abalone harvesting was serious, but it seemed it was also too big to police.

Emma made her way through the low, hardy vegetation and then decided that instead of running on the flat beach she would try the steep sandy path up the Blesberg. She’d only gone a few metres when she saw a mound of opened shells, lying in the bush. She crouched and picked one up and, as the coastal breeze shifted, a foul stench filled her nostrils. She straightened and stepped back. Among the midden was a purple and black gelatinous goo, rotting away. She looked at the shell; it was as big as her palm, and scraped clean.

Abalone.

This was what Denzel and his friend had been after. Sickened, Emma tossed the shell back on the pile and turned away. She started violently when she found a man right behind her.

Denzel.

As Emma started to raise one hand protectively, Denzel’s fist shot out, Emma’s head snapped back and she fell into the sand and the tangle of bush. He fell on her, punching her again, then put a hand over her mouth. In his other hand he held a knife.

Emma tried to scream, but he clamped her cheeks, painfully. The blade scratched her through her shirt, over her shoulder to her upper arm, where Denzel sliced through the band holding her phone. He moved the knife to her neck and terror and panic overwhelmed her. She tried to remember something – anything – Sonja had ever taught her about self-defence as Denzel put his knee between her legs and began to force them open. Emma tried to bite his hand, but she felt the knife pressing into her skin. He smiled at her.

A dog barked.

‘Hey!’ a man yelled from the pathway below them.

A Doberman came bounding up the steep hill, paws scrabbling for purchase in the loose sand. Denzel looked over his shoulder; he grabbed Emma’s phone, got up and ran off.

Sonja put Emma to bed.

She stroked her daughter’s hair and passed her another tissue so she could wipe her eyes. The sight of Emma’s cut lip and the swelling around her cheek made Sonja clench her jaws together so tightly she thought she might shatter a tooth.

The police officers had left after taking Emma’s statement and that of the man who had found her. Sonja had thanked the man profusely. The female officer had said that the description of Denzel and his name were not immediately familiar, but that many local men had joined the ranks of abalone poachers.

‘I’m sorry,’ Emma said once again.

Sonja laid her fingers softly against Emma’s cheek. ‘I told you already, four times now, you have nothing to apologise for.’

‘You warned me about running at dusk.’

‘Shh. It was still light. You are not at fault here, that boy, Denzel, is.’

An ambulance had also come, called by Sonja as soon as she saw the state of Emma, even though her daughter had tried to protest that she was all right. Sonja popped one of the Valium the paramedics had left out of its foil pack. ‘Take this.’

‘I’m OK.’

‘It will help you sleep.’

Emma sat up in bed and took the pill.

‘You’re sure he didn’t –’

‘Mum . . .’ Emma said, ‘I told you, he hit me and took my phone off my arm. It was my own stupid fault for taking that video of him.’

‘No.’ Sonja balled her fists. ‘You are not to blame in any way for this.’

‘And now I’ve lost my phone . . .’

‘It’s just a phone, Emma. We’ll buy you a new one tomorrow, if you’re up to it. We can go into town, play tourists, go shopping again.’

Emma gingerly touched her cheek. ‘I can’t go out looking like this.’

‘You can.’

‘Mum?’

‘Yes?’

‘Will you teach me to fight?’

‘We’ll talk about that in the morning.’ Sonja sighed and rubbed her forehead. She had the makings of a hangover after her lunchtime drinking. Emma closed her eyes and Sonja left the bedroom, quietly closing the door.

She went to her own room and dragged her military-green vinyl dive bag from the closet. She hefted the bag onto her bed and unzipped it, then selected her kit and laid it out on the bed. She had matching black Lycra leggings and a long-sleeve T-shirt from her selection of workout gear, which would do fine, and a lightweight black beanie. She also took out the weighted dive belt she’d had on earlier that day; the knife was in its scabbard. She unsnapped the fastenings on a waterproof Pelican case and took out her Glock 19 and two magazines of ammunition. From elsewhere in the dive bag she retrieved a silencer and screwed it onto the end of the Glock.

Into a small, black running pack she placed cable ties and duct tape – she never travelled without either – as well as antiseptic wipes and a couple of military-issue wound dressings, just in case.

Sonja dressed, threaded a pancake holster onto the dive belt, then put it on and slid the pistol into the holster. She put on the beanie and tucked away her hair, already in a ponytail. On her feet she wore lightweight black climbing shoes. She put on a dark grey nylon windcheater, zipped it up and pulled it down low enough to cover the pistol and knife handle; that would be enough not to alarm a casual onlooker. From the kitchen she took four resealable plastic bags and put them in her running pack.

She went back to Emma’s room, opened the door a crack, and confirmed her daughter was asleep. She stopped there a moment, looking down at her. Emma would never truly know just how much she meant to her, and Sonja knew she would never be able to find the words to tell her; there were some things she just could not explain and they ran deeper than a normal mother’s love for a child. Sonja was not normal.

She didn’t bother leaving a note. If Emma happened to wake before she returned, her daughter would be able to guess where she had gone.

Outside the cottage a chilly fog, trapped by the Kogelberg behind her, was rolling down the steep mountain wall to the ocean. Sonja pressed the home button of her phone and opened the app she had installed on her phone and Emma’s. Her daughter didn’t know it, but Sonja could track her. It took just a few moments for Sonja to detect the signal from Emma’s phone. Interestingly, it was showing out in the blue of the Indian Ocean on the phone’s map screen.

Sonja walked along Watsonia Road, past holiday homes and retirement nests towards the car park by the beach. She made her way through the dunes, among the scrubby coastal vegetation. As she moved, she picked up the sound of voices, carried on the onshore breeze.

She saw people moving, silhouetted against the night sky, and dropped down into a crouch between two dunes.

A girl in her early to mid-teens struggled uphill from the beach, a bulging net bag full of abalone shells on her back. Next came a younger boy with an old backpack, which clacked with the sound of shell on shell as he walked.

Sonja dropped to her belly and leopard-crawled to the edge of the trail, hiding herself like a snake in the low fynbos.

The next person on the well-worn trail was a man in a wetsuit, barefoot, still wearing his BCD vest and oxygen tank and carrying a pair of fins. Sonja drew the Glock from its holster. As he walked past her, oblivious to her presence, Sonja sprang up, moved silently behind him and hooked her left arm around him, hand over his mouth as she jammed the tip of the pistol’s barrel up under his jaw.

‘With me,’ she hissed. She led him back between the dunes, deeper into the tangled coastal vegetation.

‘Hey . . .’ he tried to say behind her hand.

‘Shut up. Unless you’d like to die?’

He shook his head.

‘Take your cylinder and BCD off, and your mask.’ He hesitated so she shifted the pistol to the side of his head with enough force to push his head over onto his left shoulder. He undid the tank and vest and let them fall to the ground. ‘Face down, hands behind your back.’

She knelt on his back, shrugged off her hiking pack, and secured his hands behind him with a cable tie. Then she relieved him of a knife and a tyre iron, which were stuffed in his belt. She threw the lever away, assuming it was the tool he used to prise abalone off rocks and reefs.

‘What’s Denzel doing?’

‘I don’t know any –’

She smacked the side of his head with the butt of the pistol and put the barrel back to his temple. ‘You mean nothing to me. I’ve killed better men than you.’

‘He’s still diving, even in the dark. He’s always one of the last to leave. It’s getting late, though – he’ll be finished just now.’

Sonja took out the tape, tore off a strip and fastened it over the man’s mouth. Next she bound his ankles and knees with several turns from the roll. Sonja hauled on the man’s vest and dive cylinder, then left him lying in the bush and moved to the tallest stubby tree she could see. There, she cached her hiking pack and used a couple of the antiseptic wipes to clean the poacher’s mask and the mouthpiece of his regulator. She double-bagged her phone, secured her pistol back in its holster, and picked up the man’s fins.

Someone would find the diver, eventually, but Sonja planned on being long gone before then. She wound her way down through the dunes, skirting the procession of other poachers and shell bearers following the same track as the others. She assumed they were heading for the rusty bakkies in the car park.

Sonja checked her phone screen through the protective plastic layers. She could see the pulsating red dot that indicated Emma’s iPhone and waded into the ocean towards it. Another diver exited, off to her right, but paid her no attention; with her long hair concealed he probably thought she was just another poacher going in for one last look.

Glancing at the phone and then pressing the menu button on her GPS-enabled running watch, Sonja selected the compass widget and worked out a bearing towards where Denzel was currently diving. She put on the fins, adjusted the man’s mask and started finning.

Without the benefit of a wetsuit she shivered, but had long ago learned to ignore temporary discomfort. These days military people called it ‘embracing the suck’ – not complaining about things out of one’s control, such as cold or rain or heat or dust, but accepting them, even revelling in them. As a young soldier in the British Army she had been put through a gruelling special forces selection course, run by the famed Special Air Service, to prepare male and female recruits from the British Army’s Intelligence Corps to withstand the rigours of undercover surveillance operations against extremists in Northern Ireland. She had experienced near-hypothermia in the snow- and sleet-covered Welsh mountains. This was nothing.

Sonja followed the bearing on her watch, wondering how Denzel could continue stealing abalone in the dark. She had her answer when she picked up the stabbing beam of an underwater torch. She finned her way closer.

Being careful to stay behind the man with the torch, she slowed and adjusted the air in her BCD so that her buoyancy was neutral. She hung there, suspended in the chilly gloom, watching the man at work.

She picked up movement in her peripheral vision, and forced herself to hover motionless as the sleek, grey bulk of a shark cruised past. Sonja looked at the man. If he was aware of the presence of danger, he resolutely ignored it, efficiently working his tyre lever under shell after shell, prising abalone off the rocky reef and slipping each sea creature into the net bag slung around his neck.

Checking around her, Sonja finned her way close enough to confirm, by his athletic build and wavy hair billowing around him, that the diver was, in fact, Denzel. There was no sign of his offsider, the other young man who had tried but failed to calm him down on the beach.

Sonja paused to draw her knife and then closed on the unsuspecting poacher. She came up behind him, reached out and ripped his mask from his face. As his hands came up, trying to grab at whatever or whomever had attacked him, Sonja grabbed Denzel’s air hose and sliced through it. She disengaged, waiting for his next move.

She underestimated him.

Instead of panicking and finning for the surface, Denzel pulled on a slip knot or buckle and let his bag full of abalone fall to the bottom of the sea. He rolled onto his back, pulled his right knee into his chest and drew his knife, which he must have retrieved or replaced. As Sonja tried to close on him again, he kicked out at her. She sliced her knife down as his fin connected with her chest. Denzel’s wetsuit protected him from the worst of the cut, but she did see some blood swirling from the wound on his leg.

Pushed back by Denzel’s kick, though unhurt because the water had slowed the momentum, Sonja swam out of his reach. She had the benefit of oxygen. He gave her a final glare, then headed for the surface.

Sonja headed back to shore, as fast as she could, knowing that she would have the advantage of speed unless Denzel ditched all of his now useless, heavy diving gear; she doubted he would. When she neared the beach she paused to unbuckle and jettison her stolen cylinder, BCD and fins. She emerged from the water cold and wet, but satisfied.

As she trudged through the sand back to where she had left her pack, she took her phone out of the plastic bags and called the number she had saved, that of the police officer who had interviewed Emma.

‘Get down to Silver Sands Beach, now,’ she said without preamble when the woman answered her phone.

‘Who is this?’

‘Denzel, the boy who beat the English girl and stole her phone, will soon be getting out of the water. He’s bleeding, though, so maybe a shark will get him first.’

‘Mrs Kurtz, is that you?’

It was ‘Ms’, but she said nothing and ended the call.

Sonja took up position in the sandhills and watched the granite-like surface of the water. All the other poachers had given up for the evening. Off to the west she saw a couple of people walking, perhaps the last of the bearers. She checked her phone and the app told her that Denzel, stupidly, was still carrying Emma’s iPhone, stuffed somewhere in his wetsuit. She’d made no attempt to take it from him in the water – that would have been too hard without killing him, and it would be better if the police caught him with stolen goods.

She picked up the sight of splashes out in the sea; it was Denzel, laboriously swimming back to shore. She was right, his dive gear was his life. If he hadn’t acted like such a bastard and hurt her daughter, she might almost have felt sorry for him. Sonja drew her Glock and sat waiting.

Here and there lights shone from houses set back from the beach, but there was no night life here, nor beachside bars or restaurants – the nearest place still open was the takeaway shop at the penguin colony, and that was out of sight. The last of the poachers and bearers were now struggling through the dunes.

Denzel was getting closer to shore. Sonja looked up at the sky. Venus was rising, the moon just a low-hanging sliver. She racked the Glock, chambering a round.

3

Emma woke the next morning to the sound of knocking on the door of the holiday cottage. She checked her watch on the bedside table; her neck hurt when she turned her head. It was just after eight in the morning.

‘Mum?’ There was no answer. Well rested but groggy, Emma swung her legs out of the covers. ‘Coming.’

She slid her lower jaw from side to side as she walked; it was still sore. She wondered if she had a black eye. She padded down the hallway, still wearing socks and pyjamas. On autopilot, she opened the front door.

A man stood there, holding a dozen roses – except that rather than being a delivery man, he was the friend of the man who had assaulted her.

‘Shit!’ Emma started to close the door, fear and panic rising up inside her as she remembered Denzel’s hands on her.

‘Wait, please wait.’ He held up his empty hand, palm out, and stayed back from the door.

Emma closed it to a crack, fumbled for the security chain and latched it. She’d still been half asleep, not thinking at all about her personal security despite the rawness of her injuries. If she’d had half a brain, she told herself, she would have asked who was there. ‘What do you want?’

‘I came to say sorry.’

Emma watched him. The last time she’d seen him he had been in an old wetsuit, worn and torn. Now he wore jeans, perfectly white sneakers and a pressed, collared shirt. He smiled. Any other time and place she would have fancied him.

‘Your friend fucking punched me.’

‘Yes, I heard. That’s why I brought these.’ He held out the flowers, though did not take another pace closer to the door.

‘How did you know where to find me?’

He looked at his shoes for a moment. ‘I’ve seen you, out running.’

‘So, you’re a stalker as well as a poacher?’

He shook his head. ‘No, please, no. I’m sorry.’

Emma held the front of her pyjama shirt tightly together. ‘Why are you apologising?’

‘I tried to stop him, on the beach, when you were filming us –’

‘Not hard enough.’

‘No, that other woman on the beach with you took care of that. That’s what I was about to say – I’m apologising for not trying hard enough to stop Denzel from coming at you, then, and . . . later. I don’t like seeing men treating women badly.’

Emma narrowed her eyes. ‘You still went into the water with him, like nothing happened.’

He looked down at his shoes. ‘I was wrong and I was scared, and I’m sorry for that, as well. We had it out, later, got into a fight.’

It was only when he looked up that Emma noticed that he, too, had a cut over his eye. She nodded towards it. ‘He did that to you?’

‘Yes. Though I hit him as well. He’s my cousin.’

‘Your cousin the poacher.’

He frowned, glanced down at the flowers and then held them out again.

‘I’m not taking anything from a poacher.’

‘I’m not a poacher. That was my first time in the water with Denzel, and I didn’t take any abalone. My heart wasn’t in it after all.’

‘After all?’

‘I’m studying at varsity and I lost my job as a waiter. I’m stacking shelves at Pick n Pay at the Waterfront, but I’m short for my fees and I needed to get some cash. I knew Denzel was poaching; he’d asked me many times to join him, but I always said no. He told me I could make fourteen hundred rand, nearly a hundred US dollars, per kilo taking abalone, and that I might be able to get eight or nine kilograms in one dive. I think poaching is terrible, but . . . Well, having no money is no excuse, but I’ve never broken the law in my life.’

‘Yeah, right,’ Emma said.

‘You sound like you’re from overseas,’ he said, ‘but not everyone in Africa is a criminal.’

Emma closed her eyes and put a hand on her forehead. She felt a pang of guilt – she had, borderline, insulted him. His words had got under her armour, and he did seem genuinely contrite. ‘You want a cup of coffee?’ She opened her eyes and saw, just then, how his widened.

‘I just came to drop off the flowers and say sorry.’

Emma slid the security chain across and opened the door. ‘Come in.’

‘You sure?’

Emma glanced over her shoulder. ‘My mum’s in her room. She has a gun. Maybe two.’

‘Noted.’

Emma stepped back as he walked in. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Oh, sorry, it’s Kelvin.’

‘Come in,’ Emma repeated, opening the door fully for him and taking the flowers when he offered them to her again. ‘I’ll get some water for these.’

Kelvin looked around as she led him along the corridor to the kitchen. ‘Nice place.’

‘It’s an Airbnb.’ Emma filled the kettle. ‘Coffee?’

‘Please. Where do you usually live? England?’

‘Scotland. I studied there, at university, and liked it, so I got a job there and ended up staying.’

‘So I was right; you’re not local.’

She shook her head and took two cups out of the cupboard. ‘I’m not. My mum’s Namibian-German, but her mother, my gran, was English, so I grew up in England and went to school there. My mum was away, on business, a lot of the time.’

‘What does she do?’

Kelvin seemed nice enough, unlike his cousin, and Sonja was only a scream away, but Emma had always felt a need to be careful about describing what her mother did for a living. She had gone through stages in her life when she’d been honest about it, but as a child this had often led to people bullying her, accusing her of lying. ‘She’s a personal trainer.’

Kelvin nodded. ‘She certainly looked fit. Sorry, I didn’t mean that to come out sounding weird.’

It was Emma’s turn to laugh. She couldn’t tell Kelvin that her mother kept fit training other people to kill, nor that she had shot more people than Emma could possibly have imagined during her career as a mercenary. To change the subject, she asked, ‘What are you studying?’

Kelvin smiled. ‘Medicine. My mom was so proud – I’m the first person in the family to go to varsity. I was stupid getting involved with Denzel. If I’d been charged by the cops it wouldn’t have been good for me.’

The kettle boiled and Emma poured. ‘So, you and Denzel?’

He shook his head and whistled through his teeth. ‘He’s been in trouble since we were kids. I can’t tell you how sorry I am.’

‘Tell the police.’

Kelvin looked away, out through the kitchen window at the view of the nature reserve. Emma handed him his cup and he nodded his thanks.

‘I take it you didn’t see him attack me in the dunes?’ Emma pressed.

He looked her in the eye. ‘No. If I’d been there it wouldn’t have happened.’

‘Yet my mum had to stop him from assaulting me on the beach.’

‘Because I couldn’t get to him first.’

‘So, go to the police,’ Emma said again, ‘tell them what he’s like.’

Kelvin paused. ‘His father, my uncle . . .’

‘What about him? You’re scared of what your uncle will say about his son who beats up women and robs them?’

Kelvin looked away again. ‘It’s not what he’d say, it’s what he’d do, especially if he knew the police were involved.’

‘What does your uncle do?’

Kelvin said nothing, just stared out the window.

‘Answer the question.’

Both Emma and Kelvin turned at the sound of Sonja’s voice. She’d arrived from her room without a sound, thanks to her bare feet. She wore a man’s blue cotton Oxford shirt, sleeves rolled up, the tail barely covering her pants. Emma knew the shirt had been Sam’s. Sonja pointed her Glock at Kelvin, who set down his cup and put his hands up.

‘Please . . .’

‘It’s all right,’ Sonja said, ‘I won’t kill you. Not immediately. I’ve been listening to your bleating.’

‘Ma’am, I’m sorry, I –’

‘Save it. Who’s your fucking uncle?’

‘Ma’am –’