8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

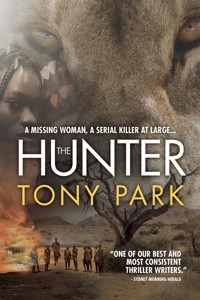

A missing woman, a serial killer at large. Man is the most dangerous quarry of all.

Safari guide and private investigator Hudson Brand hunts people, not animals. He’s on the trail of Linley Brown who’s been named as the beneficiary of a life insurance policy.

Linley’s friend, Kate, supposedly died in a fiery car accident in Zimbabwe, but Kate’s sister wants to believe it is an elaborate fraud.

South African detective Sannie van Rensburg is also looking for Linley, as well as a serial killer who has been murdering prostitutes on Sannie’s watch. Top of her list of suspects is Hudson Brand.

Sannie and Hudson cross paths and swords as they track the elusive Linley from South Africa and Zimbabwe to the wilds of Kenya’s Masai Mara game reserve.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

About The Hunter

A missing woman, a serial killer at large. Man is the most dangerous quarry of all.

Safari guide and private investigator Hudson Brand hunts people, not animals. He’s on the trail of Linley Brown who’s been named as the beneficiary of a life insurance policy.

Linley’s friend, Kate, supposedly died in a fiery car accident in Zimbabwe, but Kate’s sister wants to believe it is an elaborate fraud.

South African detective Sannie van Rensburg is also looking for Linley, as well as a serial killer who has been murdering prostitutes on Sannie’s watch. Top of her list of suspects is Hudson Brand.

Sannie and Hudson cross paths and swords as they track the elusive Linley from South Africa and Zimbabwe to the wilds of Kenya’s Masai Mara game reserve.

For Nicola

Contents

Prologue

Hazyview, South Africa, June 2010

Captain Sannie van Rensburg looked at the vultures in the trees and shuddered. OnlyinAfrica, she thought. She took a pair of rubber gloves from the packet in the boot of her Mercedes and snapped them on.

Two officers, a man and a woman in the blue-grey uniforms of the South African Police Service, were standing over the body, and the latter kept glancing up at the vultures, her right hand resting on the Z88 pistol in the holster that perched on her rounded hip. Sannie greeted them.

Her new partner, Mavis Sibongile, exchanged muted greetings with the officers and hung back. Sannie stepped over the rocky ground, winding her way carefully between the stubby thornbushes, and made her way to the bundle wrapped in black builder’s plastic that lay at the officers’ feet. ‘Who found her?’

‘A woodcarver,’ said the female officer. Sannie liked her braids. The officer pointed at a man squatting twenty metres away. The old man didn’t look at her. ‘He makes giraffes and lions and chickens for the tourists. He was in the veldtlooking for a tree to cut down when he came across her.’

Sannie ignored the witness for the moment and knelt down beside the bundle. A hand – or, more correctly, the remains of a hand – protruded from a ragged tear in the plastic. Sannie saw the hyena spoor in the dirt. ‘Were the hyena still here when the man found the body?’

The male officer called the question to the woodcarver, who responded in Tsonga. Sannie didn’t need a translator. ‘Yes, they were,’ the man said. ‘I threw some rocks at them and they ran off.’

‘What time was this?’ She peeled back some more of the plastic.

‘Just after dawn.’

The hyena couldn’t have been here long, she thought. If the nocturnal animals had been on the body all night they would have made short work of the plastic, and the woman wrapped inside. A Kombi towing a caravan slowed on the main road, the family inside staring at the parked police bakkieand the people in the bush. Four hundred metres up the road was the Phabeni Gate entrance to the Kruger National Park. ‘I want this area cordoned off,’ Sannie said to the uniforms. ‘No more walking around here. We need to check for footprints.’ She looked at her new partner, who was still hanging back. ‘Mavis, come help me,’ Sannie said.

Mavis was half her age, a university criminology graduate who had enlisted into the SAPS on an accelerated traineeship. Sannie had retired from the police before she’d turned forty, then returned as a police reservist to help cover manpower shortages in the Nelspruit serious and violent crime unit. Like an addict she had been unable to give up the job completely, no matter how destructive the drug, and she had allowed herself to be talked into returning to work fulltime as a detective captain in a mentoring role for new officers. Her husband, Tom, an Englishman, had also once been a police officer, but had now taken to running the family’s banana farm with the vigour and optimism of one who had been brought up in a city all his life. He had been against her going back to work, but loved her enough to give up trying to talk her out of it when he realised he would never win that argument.

Sannie looked at Mavis’s high-heeled boots. She would have to have a quiet talk to her, again, about appropriate clothing for this job. ‘Help me unwrap her some more.’

Flies buzzed and took flight as Mavis dropped hesitantly to one knee and the two women started to unroll the body. Mavis gagged. Poor girl, Sannie thought. She would probably be sick. ‘If you must be sick don’t do it close to the crime scene.’

Mavis swallowed hard and nodded. A face emerged from the plastic; eyes wide and ligature marks immediately visible around the neck. She had been a pretty girl, perhaps aged nineteen or twenty, maybe twenty-one. She wore purple eye shadow and her curly hair had been cropped close to her scalp. There were gold hoop earrings, still in place.

‘Her …’ Mavis swallowed again, ‘her wrists have been tied as well.’ She held up the pulpy, bloody mess and showed Sannie the marks on the girl’s skin.

‘Naked,’ Sannie said as they unrolled further, revealing more skin. ‘Ag, cigarette burns on her breasts.’

‘Who does such a thing?’ Mavis asked.

Sannie wanted to be home, right then, with her husband and her three children, not in this field of scrubby thorn and death. The carver was glancing over at them. ‘Boyfriends, husbands, fathers, gang members, random rapists; it’s our job to find out who.’

There were other lacerations and bruises on the breasts, as though she had been tied up, and perhaps beaten with something. Sannie shook her head. As she moved away more of the plastic she saw the coagulated blood and the first of the cuts. Beside her, Mavis stood and rocked on her high heels.

‘I’m sorry …’ She put her hand to her mouth and turned and ran. Sannie steeled herself as she uncovered the woman’s groin. The insides of her thighs were coated with dried blood. She saw the incisions and knew this had been more than a rape. Whoever had done this had tortured this poor girl and, by the looks of it, plunged a knife between her legs, inside her body. She fought back the rising tide of bile and, as much as she wanted again to be away from this evil, from this depressing job, she knew she could not go back to her home in the hills and live the life of a farmer’s wife. No matter how many horrible things she saw, this was what God had put her on earth to do; that and raise her own children in safety and love her husband.

The politics of the job and the new South Africa dismayed her on a daily basis, and in a way she wished she could be like those who turned their back on it and said to hell with them all, but when she looked into the wide, pain-filled eyes of the dead girl and imagined her last moments on God’s earth she knew she could never walk away.

‘Clean yourself up, Mavis,’ she called to her partner, who was bent double. ‘We’ve work to do.’

1

Kruger National Park, South Africa, 2014

Hudson Brand watched the lion jump over the guardrail and onto the bridge over the Sabie River.

‘Shoot,’ he said.

‘Shoot what?’ the man wearing South African National Parks khaki behind the register in the Paul Kruger Gate office asked him.

‘Nothing. It’s a euphemism for shit.’

‘You Americans are funny, Hudson, and …’

Brand didn’t hear the rest of the man’s sentence. He was already out the door of the gate office. ‘Get back in your cars,’ he yelled to some tourists who were oblivious of the big black-maned cat walking towards them from the other end of the bridge.

The lion was silhouetted in the dawn’s half-darkness by the headlights of three cars that were following it along the bridge. At Brand’s end, tourists checking into the Kruger National Park had faces and cameras pressed to the window of the thatch-roofed gate office, watching the lion’s progress as it passed the last of the cars in the long holiday weekend queue that stretched from the office back a third of the way down the bridge.

Brand had been glancing out the window, checking on his lone client in the Land Rover game viewer while the national parks guy was processing his paperwork, when he’d spied the lion. His first clue that something was amiss was the cars that had stopped at the far end of the bridge. The Paul Kruger Gate was like rush hour at dawn every day, with staffers in a hurry to get to their jobs at Skukuza, the park’s main camp situated twelve kilometres inside the reserve, and tourists in private cars and safari vehicles, like his, coming in for the day or overnight stays. No one stopped at the far end of the bridge without good reason. As a guide and a private investigator, Brand knew that changes in the natural pattern of things often signalled that something interesting – and potentially dangerous – was about to happen.

At first Brand thought the movement in the lead car’s headlights was the big male leopard whose territory encompassed the bridge and gate, and the Sabiepark Private Nature Reserve across the river from Kruger. Brand had seen the big muscled tom, who had the bulk of a lioness, a few times on the bridge, and even on the main road outside the park when he’d been bringing guests in early. The leopard came and went from the protected reserve as he pleased and didn’t give a damn about the rules or the people outside Kruger, some of whom would have gladly killed him to stop him eating their goats or dogs or whatnot. But this animal was bigger.

‘There’s a lion coming towards you,’ Brand said to the nearest couple of tourists, who were standing nearby, poring over a map book on the bonnet of their rented Corolla.

‘Leone?’ said the man, who sported an Andre Agassi bandanna.

‘Si,’ Brand replied.

Mobile phones were drawn faster than six-shooters as word rippled down through the parked cars in the queue. Some people were jumping back inside, slamming the doors on their BMWs and Kombis, others were getting out. Camera flashes popped like far-off white phosphorous rockets, marking targets in the bush.

Brand’s mobile buzzed in his pocket. He quickly checked it. There was a message from a fellow guide, Bryce Duffy, a young South African guy of English descent, originally from Durban. I’minthe queue–checktheliononthebridge. Brand looked up and found Bryce’s Land Rover a few cars back in the slow-moving procession that was following the lion. Bryce must have spotted Hudson’s vehicle parked near the office.

Brand double-checked his own vehicle and saw Darlene, his lone client for the day, climb down out of the game viewer.

‘For crying in a bucket,’ Brand said. He strode down the line of cars to where his game viewer was parked.

The lion was calling as he padded along the tarmac towards Brand. The low throaty rumble got to Brand every time; it was what kept him in Africa, what made this continent, and not the place where he was born, his home. Part of the attraction, too, was the edginess of this part of the world and the fact that danger could and did rear its head with no notice. Like it had now.

‘Darlene, please get back in the truck,’ Brand called as he picked up his stride.

Amateur photographers were piling back into their cars as the king of beasts sauntered past them, hardly deigning to dignify his laughably lesser subjects with a glance. He had other things on his mind; food most likely, perhaps sex. NowonderIlovelions, Brand thought.

Darlene was holding her tiny digital camera out at arm’s length. The inbuilt flash kept popping off but the lion, who Brand could now recognise as Pretty Boy, a member of the Mapogo coalition, was still too far from her for the flash to be of any use. Pretty Boy was maybe a hundred metres from Darlene, but he was closing fast with that effortless, distance-covering fast walk that lions had.

Darlene looked back at Brand. She was thirty-five, newly divorced, bleached blonde and blue-eyed, with a California tan and a rack that Brand thought looked promisingly natural. ‘Get in the truck,’ he ordered her.

Darlene gave him a thumbs-up and an expensive smile. She didn’t get the urgency or realise how quickly Pretty Boy could cover the ground between him and her.

Brand kept walking towards her, pointing to the truck and using the queue of cars as cover. He didn’t want Pretty Boy taking a bead on him as the only biped still moving on the bridge. Brand was sure that as long as no one did anything stupid Pretty Boy would just keep on walking briskly by, and then peel off into the bush once he reached the statue of OomPaul Kruger. The old president’s big fat face with its leonine beard somehow still managed to dominate the entry and the name of South Africa’s flagship reserve, despite the fact that every other Afrikaner name was busily being changed throughout the country.

But this was the Kruger Park, and Brand knew well that people on holiday and even those who worked here, living cheek by jowl with the Big Five and possibly feeling a false sense of security, did some stupid things. As if to prove him right, a car raced onto the bridge, its driver seemingly oblivious to what was happening up ahead. It was a VW Golf with dark tinted windows, and even from the other end of the bridge Brand could hear – and feel – the thump of deep bass speakers from inside. Brand assumed this was a national parks staff member, who would have a pass they could use to leapfrog the queue of tourists’ private cars and open game-viewing trucks like Brand’s.

‘Shoot,’ Brand said.

Darlene was grasping the side ladder to haul herself back up into the game viewer, but she was still holding her camera in one hand. She looked up at the bridge when she heard the sound of the speakers and the speeding engine, and saw that Pretty Boy was now a whole lot closer.

The staff car saw the lion, at last, and hit his brakes. Rubber painted the tar surface and the little car fishtailed as it skidded. Pretty Boy looked over his shoulder and gave an angry roar.

Darlene’s digital camera clattered to the roadway and she lost her footing, her rubber sandal slipping on the bottom rung of the ladder as she tried to climb faster, but with only one hand on the ladder. Her feet touched the ground again.

The car had come to a halt, but Pretty Boy had decided it was time to fight rather than flee. Lions were like that, Brand mused. Catch them on foot and ninety-nine times out of a hundred they would see you first and get up from their daily snoozing and run away. Surprise one, or corner one, and the instinct to kill took over from the urge to retreat.

Pretty Boy vented his anger at the hapless driver and Brand reckoned he could see the little Golf rocking under the acoustic onslaught.

Brand found himself running – something he knew he should definitely not be doing in the vicinity of a fully grown lion – and Darlene looked like Brand felt in his nightmares. He had the same dream often; he was back in Angola, trying to run from a smoking, ambushed Ratel armoured vehicle, while the Cuban-manned T-54 tank slowly traversed its turret for the killer shot. His legs always felt as though they were encased in lead, and when he pointed his R5 at the tank commander the trigger never worked.

Darlene looked from the lion back to Brand and did what he was doing – she ran.

Brand was running towards the lion, which was stupid enough, but what Darlene was doing was suicidal. Brand saw Pretty Boy’s head flick from the car to the woman. The big beast flattened his ears back, tensed and lowered his whole body, like an aircraft carrier jet pilot bringing his engines up to full power just before the catapult flings him down the deck.

Darlene only had the chance to run four or five metres. That was because she ran slap bang into Brand. He had darted between a Discovery and the front bullbar of his Land Rover Defender game viewer. Brand feared for a moment Darlene might knock him over, but he caught her, grabbed her forearm and pulled her behind him.

Pretty Boy launched, and Brand felt that in all of his twenty-five years of being a safari guide he had never come so close to losing control of one or more of his bodily functions. He had seen lion charges and kills plenty of times over the years – enough to know he never wanted to see a maned missile aimed at him, on foot.

The urge to flee was as strong in Brand as it was in any other creature being preyed upon in the bush. His mind, however, told him he could not run from Pretty Boy because if he did then he, or most likely Darlene, would be dead within seconds. Also, the lion would be killed if it took out a human.

Brand fought the urge to run and raised his arms high above his head and roared back at Pretty Boy as the lion charged him with the speed of a rocket-propelled grenade. As he had on a few other occasions in his life, Brand thought he was dead; never this scared, but dead, for sure.

Just as the Golf had slid to a crazy halt, so, too, did Pretty Boy. The lion stopped no more than a metre from the couple, and when he roared Brand felt the sound waves shake him like a spindly sapling in a gale. He felt Pretty Boy’s hot breath wash over him. Darlene screamed as she clung to Brand’s back, and he felt her face burrow into the weave of his khaki bush shirt. Around him he was dimly aware of voices, and the blinking of camera flashes.

As he waited to die Brand had the sudden thought that if Pretty Boy killed them now then he and Darlene could at least go to their deaths knowing their last moments would go viral, and if someone in the queue had the presence of mind to turn on their video camera then they would be enshrined forever as YouTube’s most viewed and stupidest victims.

Pretty Boy roared again and Brand called back until he was hoarse, though he knew he could not compete with the king, the top of the food chain.

‘Go on, get!’ Brand croaked. Then, because Pretty Boy was a South African lion, he added: ‘Voetsek.’

Pretty Boy suddenly seemed to notice the crowds of people and the camera flashes. He shook his head and trotted away, across the grass and into the bush behind the statue of Paul Kruger’s head.

A Land Rover roared up and stopped beside Brand. Bryce Duffy was grinning. ‘Gutsy move, Hudson. You OK, bru, or should I get you a spare pair of shorts?’

Brand exhaled. ‘A bottle of bourbon and a pacemaker wouldn’t go astray.’

*

Like many old soldiers, Brand was an easy sleeper, but a light one. He had taught himself to grab some shut-eye whenever the opportunity presented itself, whether in pouring rain or the heat of the African day. By the same token, the smallest of noises would bring him alert instantly, sometimes searching for the rifle he no longer carried, all his senses pre-programmed to cry out ‘danger’.

At the sound of the gentle, hesitant knock on his door his eyes were open. He got up, dressed only in boxer shorts, and padded over to it.

‘Hudson,’ a woman’s voice whispered.

Brand coughed. He had tried to give up smoking many times over the years, and had been free of tobacco for four weeks, but one of the camp’s guests, another of his erstwhile countrymen, from Virginia, had produced a cigar after dinner. Brand hadn’t been able to say no. Alcohol, women and tobacco had always been his weaknesses.

‘Can I come in?’ said the voice, a little louder now in case he was still sleeping.

For a moment Brand considered feigning slumber. That would have been the right thing to do, the professional course of action, but Darlene had taken a foolish risk coming to him in the dark alone.

He opened the door. ‘You shouldn’t have walked here without a security guard. You knowhow dangerous this country can be.’

Darlene was an animal nut and Brand’s job that day had been to take her into the Kruger Park for a five-hour game drive, followed by a transfer into the neighbouring Sabi Sand Game Reserve, to a luxury lodge called Leopard Hills. She’d wanted to maximise her time seeing Africa’s wild animals.

It had taken them an hour, though, over breakfast at the Skukuza Golf Club, to recover from the meeting with Pretty Boy on the bridge. After that Darlene had moved from her spot in the first tier of seating behind Brand to the front passenger seat beside him for the rest of their game drive. They’d laughed, eventually, about the lion, and he’d shown her more, as well as buffalo, rhino, zebra, giraffe and a variety of antelope before they’d left the park and driven into the private reserve.

Brand had lunched with Darlene at Leopard Hills. The lodge was set in a pile of granite koppiesoverlooking a waterhole, where a giant bull elephant had drunk while they ate on the viewing deck under a market umbrella. He’d then accompanied her on the afternoon and evening game drive in a Leopard Hills Land Rover. Ordinarily he might have skipped the drive, preferring to let the lodge’s guide take the reins, but he was feeling a connection to Darlene. Perhaps it was shared adversity, the thrill of surviving a near-fatal moment, he thought; or perhaps it was her perfume and her legs.

At dinner they’d put away a four-course gourmet meal and too much beer, wine and Amarula liqueur, which should have rendered them both unconscious by this late hour. But Brand knew that surviving danger did strange things to the human body, especially the libido. It gave men and women strength and stamina beyond their normal capabilities and, when members of the opposite sex were in close proximity it brought on a powerful urge to procreate, or at least go through the motions.

‘I’m too scared to sleep alone,’ Darlene said.

She had lingered at the entrance to her own suite after dinner, standing in the dark while the lodge’s security guard waited patiently for them to say goodnight and scanned the bush around them with a torch in search of night-time predators and buffalo. Darlene had thanked Brand, again, for rescuing her that morning, and turned in. In truth, Brand knew the credit for their survival lay with Pretty Boy Mapogo. The lion could have killed him, or her, or both of them before any firearm could have been located in the gate office or the glove compartment of some tourist’s Audi to stop him. Pretty Boy had charged and Brand had stood him down, but Pretty Boy had made the call that it wasn’t worth his while killing the defenceless humans.

Brand believed the lions in the Kruger Park and elsewhere in Africa were taught, probably by their mothers, what they could and couldn’t eat. Poor Mozambican illegal immigrants walking across the park in search of a new life in South Africa: yes. Rich white foreign tourists and heavily armed game rangers: no. Pretty Boy had let them live, but now that Darlene had slipped back to his room, he wasn’t going to give the lion all the credit.

‘Come here,’ Brand said, his voice rough from the cigar. He fancied he saw her shiver a little in the moonlight, despite the night’s heat. She had changed into shorts and a T-shirt. Brand knew he should call the security guard and have the man walk her back to her suite, but instead he led her inside. His curtains were open and beyond the balcony he could see a sky studded with stars.

The king-size bed was encased in starched white cotton of a high thread count whose cool crispness contrasted nicely with the scarred skin of his back and the warm softness of Darlene’s breasts as she pulled off her T-shirt and snuggled up to him.

‘You saved my life,’ she whispered in Brand’s ear as he enfolded her in his arms.

‘It was the lion,’ Brand confided to Darlene in between deep, sensuous kisses. ‘He did the smart thing and overcame his initial urge to kill us.’

‘I have urges too,’ she said into the side of his neck as he felt her hand move down between them.

Darlene’s body was lean and angular, her muscles firm. Her body felt sculpted, the artist some part-time surfer or ex-Marine personal trainer cashing in on the housewives and divorcees of Orange County. There was a hardness to her. Brand recalled that she was an executive in an IT company of some sort. He was sure she went about her business with the same single-mindedness and methodical efficiency as she was now using in going after him.

Her hands were on him, then her mouth and, wanting to prolong the experience, Brand brought her face back to his and kissed her deeply as he opened her with his calloused fingers. In the moonlight he could see her eyes, and the tear that formed at the corner. Her sexual aggression was a mask; she was still shaking inside. He kissed the teardrop away. ‘You’re safe, now.’

‘It’s not the lion,’ she whispered, and turned her head on the pillow. Brand stopped touching her, hovering above her on one elbow.

‘Am I your first, since the divorce?’

Darlene nodded. ‘I’ve never been with any man other than my husband in all my life.’ A new tear formed and rolled down her cheek.

Brand took her chin between his thumb and forefinger and turned her pretty face to him. ‘You’re beautiful, Darlene, and he was a fool to lose you.’

She started to speak, but Brand let go of her chin and put a finger to her lips. He felt the taut muscles of her thighs ease as he moved his other hand down her body. It would have been easier for Brand if hers was just another case of khaki fever, but there were other issues at stake here and he did not want to hurt her.

What would it have been like, he wondered, as he kissed her again, to have been with just one woman? The African fish eagle mated for life, as did the dainty little steenbok, so the concept was not without precedent in his world in the African bushveld.

‘Please,’ she said, and that was all he needed to hear.

2

‘My name is Linley Brown and I’m a drug addict,’ I said to the group.

‘Hi Linley,’ came the ragged reply, which echoed slightly in the empty church near Sandton City, Johannesburg’s shopping mecca. The eight others were mixed in every sense of the word; there were men, women, blacks, whites, an Indian and a coloured. The demographic ranged from an eighteen-year-old boy who had sold his body to pay for his habit to a well-dressed matronly Afrikaner housewife. We were the Rainbow Nation of substance abusers, and our poisons – coke, heroin, prescription painkillers (my drug of choice), tik and crack – mirrored our rich cultural diversity.

I saw my eyes in theirs: sometimes glazed, sometimes fidgeting from side to side, pupils dilated, others like pinpoints. I saw the hopelessness and the belief, probably wrong, that this time they would make it; this time they would get clean. I checked my watch. This was the lunchtime ‘express’ meeting, giving those of us with jobs time to get back to work and the shopaholics a chance to feed their other addiction after cleansing themselves, for an hour, at least.

‘It’s been sixty-three days since I took my last painkiller,’ I said. I saw the rentboy roll his eyes, as if a pill-popping white woman in her early thirties didn’t have the right to be here among the hard- core users, but everyone else smiled or nodded or murmured an encouraging word or two.

‘Do you want to tell us how you’ve progressed?’ asked Mark, the convenor. He was a good-looking guy, late twenties, and a reformed cocaine addict. He had nice eyes, and I could tell by looking at them that he had succeeded. The pupils were normal, the whites clear, but there was a soft sadness to him, as if he would carry forever the burden of the sins he had committed to feed his addiction, even if he was now free of his demons and helping others to exorcise theirs.

‘OK, I think. I still have nightmares about the car crash that killed my friend, in Zimbabwe, but like I said last time, in a funny way that’s what forced me to come here, and to take control of my life.’

‘I know it’s hard for you, but tell us a bit more about that day,’ Mark said.

I nodded and took a deep breath. ‘I was stoned at the time the car burned. We were in the hills between the Dete Crossing turnoff and Binga, heading to Lake Kariba to catch a houseboat.’

I sniffed and looked around the group. The rentboy was inspecting his fingernails, but most of the others were leaning forward on their chairs, perhaps grateful to hear a tale as sad, and possibly sadder, than their own. ‘My best friend, Kate, was driving my car; we were taking it in turns. We were on a bridge and a warthog came from the other side. Kate swerved to miss it and lost control and we went over the edge, through a section where the guardrail was missing. My car was ancient, from the 1950s. It had been my grandmother’s and it didn’t have seatbelts. I was in the back getting us drinks from the cooler box when we went off the bridge. Kate was knocked out and trapped behind the steering wheel.’ I drew a breath and screwed my eyes shut, but it was no good. ‘We were carrying a plastic container of petrol in the boot, which you’re not supposed to, but there were fuel shortages. There was a fire. I got out, went to her side to try and free her. There was nothing I could do for her, but . . .’ I opened my eyes and felt the tears flow down my cheeks.

‘Go on,’ said Mark. His eyes were searching mine, to see if I was under the influence of something. My lapse in concentration as I experienced yet another flashback to the burning car had no doubt set off some alarm bells.

‘The thing is, I can still see her body behind the wheel of the car. I can still smell her burning.’ I looked down at my nails to focus my thoughts, not wanting to hold those dark eyes any more. I’d had the French tips done that morning, as I had a job to go to straight after the narcotics anonymous meeting. The varnish was flawless and my shoes were new, pinching slightly, but gorgeous. I smoothed the silk of my dress, which cost more than that bitchy little rentboy could make in a year.

‘I have the need for the drugs, the craving, always. I wonder if it will ever go away.’ I looked to Mark and around the circle of others on their hard-backed chairs in the musty-smelling place of worship and was not encouraged. The matron looked at the floor and the rentboy at the ceiling. This was not America; there were no high fives or ‘praise-the-lord’s or ‘you can do it, girl’s. This was the new South Africa, Mandela’s tarnished dream personified in we nine, plus Mark, as we faced one new problem one day at a time. I didn’t want to be in South Africa, I wanted to be home in my native Zimbabwe, but there was no money north of the border. Like three million other Zimbabweans I had headed south to eGoli, Johannesburg, the city of gold. This was where the money and the work was, and too many people in the dwindling white community in my home country knew me for me to be able to stay there and work among them.

‘As well as thinking about the car crash I’ve also been going over, in my mind, some of the things my addiction caused me to do, or at least things that happened when I was stoned.’ This time, when I looked at him, the rentboy’s eyes were downcast. I felt sorry for him then. I had done the same as him, though not on the street. I had done disgusting things for drugs, things I would never have imagined myself doing, and perhaps our lives, our backgrounds, weren’t that dissimilar in other ways. When he looked up I gave him a little smile; if he wouldn’t support me then at least I would try and be supportive of him. He nodded in return. ‘I hate myself for some of the things I did. I want to erase that part of my life, but I know I’ll never be able to.’ I looked at Mark. ‘Perhaps there is something I can do; some sort of penance that would atone for my sins?’

‘I’m not a priest, and not even overly religious, though I do thank the church and the local minister for letting us use this place for our meetings. I can’t tell you to go and say ten Hail Marys to ease your conscience, Linley, but you do have to look forward. That’s something I can tell you from experience. You’ve made the decision to change your life and to move on. You need to define yourself by your future life and the choices you make from now on, not by your past.’

I nodded. It was easy for him to say; Mark was a merchant banker whose employer had taken him back once he had got himself clean. He wore an expensive suit and I knew he drove the latest model Audi. My clothes were a disguise, not a reflection of my way of life or my bank balance. In fact, I had nothing, not even the insurance payout, which the brokers back in England were taking their sweet time processing. When the money came through I would leave South Africa for somewhere else on the continent – I fancied Kenya because I’d never been there. I would lead a good, clean, honest life, free of all my demons, both chemical and human.

There was nothing else I could add. I looked at the diamond- encrusted Cartier watch I was wearing and my silence cued Mark to ask if anyone else wanted to contribute to the meeting.

At the end, as we all rushed back to our day jobs, someone came up behind me and touched my arm. I spun around. It was the latte-skinned boy who probably still sold himself. He took his fingers off me. ‘Sorry. I just wanted to say . . . well, I mean, like, I think I know what you were talking about in there.’

‘It doesn’t matter whether we take pills or tik or stick a needle in our veins, we’re all in there for the same reason,’ I said. He looked down again. It was my turn to touch him, on the arm, my finger connecting with his hard bicep. He kept himself in shape and I hoped he wouldn’t succumb to his habit again and risk the damage to his physical and mental health that came with it. ‘We can do it, right?’

Johnny looked up at me and I saw his eyes start to glisten. I always looked at people’s eyes before any other part of them. I could tell, now, if a person was honest or dishonest straight away, but I’d had to learn this the hard way. ‘Ja, Linley. We can. And whatever you did,’ he forced a smile, ‘it’s not nearly as disgusting as some of the things I’ve had to do.’

It was good he could laugh about his past, which might also still be his present. I smiled for his benefit, but there was too much darkness in what I had done and what had been done to me for me to ever make it the subject of a joke. I resolved not to be judgemental of him or any of the others in the group again. ‘You’ll be fine. We’ll all be fine.’

But I didn’t really believe that.

*

In the undercover car park at Sandton City I pushed the alarm thingy on the key ring and the lights on the new Mercedes convertible flashed and the door locks clicked. I looked behind me to make sure no one was following me, and eased myself into the low-slung status symbol.

The forward edge of the leather seat was cool against the skin behind my knees, below the hem of my dress. I liked the feeling, but not the smell; it brought back too many bad memories. This wasn’t my car; I couldn’t afford something like this. It was a loaner from Lungile’s brother. I plugged my iPhone into the cord and dialled Lungile’s number.

As I reversed out of the car park spot and drove out onto the street she answered and I used the hands-free. ‘Howzit.’

‘Hi, girlfriend,’ Lungile said.

I heard traffic in the background. ‘You’re finished at the salon.’

‘Yes, and I look a-may-zing, if I do say so myself.’

I envied Lungile her self-confidence, even if was sometimes just for show, or for my benefit. She had her own troubles, mostly her seriously ill mother’s medical bills. ‘I’ve finished my meeting; I’ll pick you up outside the hairdressers in about ten minutes. OK?’

‘Yebo.’ Lungile hung up.

I smiled, properly, for the first time that day. Lungile was amazing and I loved her. By the time I started school in 1986, Zimbabwe had been independent and black-ruled for six years. The president, Robert Mugabe, had been doing terrible things to the Matabele people in his first few years of office, wiping his political opposition from the face of the earth, but I was too young to know about any of that.

Unlike my parents I went to school with black kids all my life. I remembered seeing Lungile for the first time when I was packed off to high school to board. My father was against me boarding, but my mother put her foot down, for the first and probably only time in her life. Lungile had the most amazing, perfect afro I had ever seen, and when the teacher asked us all what we wanted to do when we finished school in six years’ time, Lungile said she was going to run for parliament and eventually become president. Most of the class laughed. I was a shy, scared kid with limited horizons – I said I liked the idea of working in a bank, like my mother had before she met my father – but Lungile just smiled at her mockers as if to say, just you wait and see.

But my best white friend and I both liked her and by the end of first term Linley Brown, Kate Munns and Lungile Phumla were known as the terrible triplets.

I stopped at a robot, as the locals called traffic lights in South Africa, and glanced into the rear-view mirror, not to look for potential car hijackers but to check my makeup. We were going to a big job, Lungile and I, and both of us were dressed and made up to impress. Image was everything in this city of status and designer must-haves. My throat suddenly felt thick as I saw the younger me, minus the encroaching crow’s-feet, and remembered the three of us laughing and playing pranks on the intractable girls of both colours who could not see beyond the divisions of the past to a new, fun, funky future in Africa. The only time I’d ever truly been happy in my life, except for the brief time I’d spent with my one serious boyfriend, George, was at boarding school. I blinked. Damn it, I did notneed tears now. Lungile shouldhave been in politics – our country needed someone smart and full of love, like her – and then she would not have been forced into doing this kind of job. But there was no work for her in Zimbabwe and nothing in South Africa, other than what we were about to do, that would pay for her mother’s chemotherapy.

I looked away from the mirror, out at the traffic. A guy in a bakkie tried to catch my eye, but I ignored him and floored the accelerator, trying to outdistance my memories. But they were there, behind me, always.

‘Oh, Kate, I do miss you,’ I said aloud.

*

Given the right circumstances Lungile could have been a supermodel if the whole president of Zimbabwe thing didn’t work out. She was tall, slim and fine-boned, and the four-inch patent leather red heels she wore made her tower above the two men who walked past her and turned their heads for a second glance. Her hair was straightened today, lacquered into perfectly sculpted bangs. Her lips shone with fresh gloss; she was the picture of a well-to-do black diamond trophy wife, right down to the impressive rock on her lefthand ring finger.

I stopped the Merc and she folded herself into the sports car. Outrageous shoes aside – for these were her trademark – Lungile was dressed in a demure grey skirt, matching business jacket and white blouse. She did, in fact, look amazing. ‘Howzit, sisi?’

‘Lekker,’ I said, but felt less than great. The meeting had shaken me, as it always did, and I wondered if I could stay away from the pills once I had some more cash in my purse. I couldn’t truly make a clean start with the money I made from the day-to-day work Lungile and I did so well together; I needed the insurance payout to set myself up again and I’d been surprised to learn it took months, not weeks as I had hoped, for a claim to be processed and paid. I smiled for Lungile’s benefit, but I also knew that once I had a big enough stake I would have to say goodbye to my friend. We loved each other, as long-term friends do, but I was smart enough to know that if we stayed in close contact it would only be a matter of time before Lungile’s high-living, partying lifestyle led me back to my recent excesses. She needed to end this gig as well, and I hoped me disappearing might force her to try her hand at something better.

Rosebank was one of Johannesburg’s old-money suburbs. Here the wealthy lived in fortified mansions, eschewing the relative safety of a sprawling gated kompleks in favour of high walls topped with electric fences, as well as big dogs, and armed response security. A sign on the street warned me that men with guns were but a call away.

‘Here it is, number twenty-two,’ I said. Lungile was quiet now. When we worked she was the consummate professional, not the brash party girl she was the rest of the time.

She checked her watch. ‘It’s one thirty; the real estate agent should have packed up and left half an hour ago.’ Lungile reached into the cramped back seat of the car and grabbed the red cushion decorated with a vinyl cut-out of a rhinoceros I had bought at Mr Price that morning. She undid the single button of her jacket and then her blouse, placed the cushion against her belly, then buttoned up again.

I indicated left and drove up the short drive to the electric gate. Its bars ended in sharp spikes at the top and these were crowned with wires promising several thousand volts of electricity. A Rhodesian ridgeback ran up to the bars and started barking.

Fixed to the wall beside the gate was a Pam Golding real estate ‘for sale’ sign, with professional pictures hinting at the wonders that lay beyond the fortress walls. In the lower right corner was a mug shot of the agent selling the property. His name was Frikkie. I dialled the mobile phone number under his name and he answered. It sounded like he was in his car, on hands-free.

Like most whites from Zimbabwe I had friends and relatives living in Australia and I’d visited the country a couple of times. I fancied I could do quite a good imitation of a South African living among the diaspora down under. ‘Frikkie, howzit, I’m outside number twenty-two, at Rosebank. I’m over here on holiday from Australia and I’m really interested in buying in this neighbourhood. My husband and I have had enough of Australia – it’s too boring and over-regulated.’

‘Ag, no, but I’m sorry,’ Frikkie said, ‘I’m on my way to another house showing. The open house for number twenty-two finished at one o’clock. Can we maybe make a plan for me to meet you there tomorrow?’

I already knew Frikkie’s schedule – it was easy to deduce from the advertised listings on the property company’s website – and he was busy for the next three hours at least. ‘Sorry, but I’ve got to fly back to Sydney this evening on the six o’clock flight. I was just out shopping with a friend of mine and we passed this place on the way. From the pictures it looks ideal. My husband told me not to leave South Africa without making an offer on something and, well, I’m worried I’ll be in trouble now, Frikkie.’

There was a pause as he deliberated. The South African property market was flat and there was nothing like the sound of a foreign accent and the promise of overseas cash to get a real estate agent’s pulse pumping. ‘I’ll have to call the owner. Maybe the maid can let you in if she agrees.’

‘That would be so good of you, Frikkie.’ I gave him my mobile number and hung up. While I waited I reached out the car window and pushed the button on an intercom mounted on a pole.

‘Hello?’ said a voice from inside the house.

‘Is the madam home?’ I asked into the intercom, knowing full well she was not.

‘Ah, no. She is not back until five.’

‘We want to come inside and look at the house.’

‘Ah, no, it is not possible,’ said the maid, her voice distorted by the tinny speaker.

My phone rang and Lungile winked at me. ‘Howzit, Frikkie,’ I said, recognising the number.

‘Fine, and you? OK, the owner, Mrs Forsyth, says you can go inside and have a look. She’s calling the maid now.’

I thanked him and promised I would call him back to let him know what I thought of the place.

A woman in a brightly printed pinafore emerged from the house and walked down the long curving driveway. Her accent had sounded Zimbabwean and she looked like a Shona; it wouldn’t be unusual for Mrs Forsyth’s maid to be from the same bankrupt country as Lungile and me. We all did what we could to survive. The woman went to the ridgeback and grabbed it by the collar, silencing it, then pushed a remote and the spike-topped gate rolled open. I drove up the driveway and we got out of the car while the maid closed the gate. My heart changed gear; this was almost as addictive as the pills.

‘Hello, how are you, my name is Patience,’ said the maid, who was sharp-eyed and stick insect-thin. ‘The madam says I am to show you around.’

‘Kanjane, sister,’ Lungile said to the woman, then continued on in Shona. Lungile was Ndebele, but had learned the politically dominant tribe’s language far better than I had at school.

The maid’s face softened a little and she smiled as she replied in the same language. Like me, Lungile had immediately recognised the woman’s accented but precise English. It helped ease the situation a little, for all of us.

Patience led us into the house and the ridgeback, sensing all was OK, nuzzled me as I walked. I held out my hand and let him sniff me, then patted his head. ‘Hello, beautiful.’ He panted with pleasure as I stroked him.

The home was even nicer than the pictures on the sale board had indicated. Patience led us through a grand reception area with a marble floor out to a central courtyard dominated by a swimming pool. All of the bedrooms faced onto the pool. The furniture was typical Joburg – big and over the top. I would have gone for something more minimalist. It was interesting, visiting so many other people’s homes, learning about their tastes and their secrets.

I walked around the lounge and let Patience show us the home cinema room. Mostly the home looked like it had been decorated and furnished by a professional designer; there was little in the way of family photographs or the clutter that had always been a part of my family home, growing up in Bulawayo. Behind a bar, though, I saw something that made me stop. It was a plaque bearing the Maltese Cross badge of the Rhodesia Regiment, which was manned by national service soldiers during the Bush War. My father had served in the regiment. Lungile’s father had been a guerrilla leader; such were the ironies of life in our country. I mused silently about how very different my life would have been if Lungile’s father had killed mine.

‘Is the madam from Zimbabwe?’ ‘Yes,’ said Patience.

‘And the boss?’

‘Ah, he is dead, of the lung cancer. Just last month.’

Lungile and I exchanged glances, then she put her hand to her mouth. ‘Oh my God, sorry,’ she mumbled. ‘I think I’m going to be sick.’

Patience’s eyes widened. I patted my stomach and pointed to Lungile’s. ‘It’s the pregnancy.’

‘Ah, shame,’ said Patience.

‘Toilet,’ gargled Lungile.

The maid nodded and led her briskly down the corridor.

‘I’ll just look around a bit,’ I said, but Lungile was running now, and Patience was trying to overtake her and give her directions to the bathroom in Shona.

I found the master bedroom and went to work. The one bedside table’s drawers were empty so I went to the other. In the top drawer was an expensive man’s watch, which I dropped into my shoulder bag, along with a last-year’s model BlackBerry, which had probably been replaced by a newer model when Mrs Forsyth’s contract had come up for renewal. Either that or, like the watch, it was her late husband’s.

I went to the walk-in closet and started going through the drawers there. In the second was her jewellery box. I tipped the contents into the bag. On the opposite side were the late Mr Forsyth’s clothes. She hadn’t got around to donating them, or perhaps she couldn’t bear to part with them. I wondered if he had served with my father – it was a big unit, but it was possible – and not for the first time in recent memory I hated myself.

Perhaps the Forsyths had left Zimbabwe at independence, in 1980, or even earlier, for they had obviously done very well for themselves here in Johannesburg. There were no pictures of children or grandchildren, so I imagined they were childless. I forced myself to stop thinking about them, and what the impact of what I was doing would be on someone recently widowed.

I heard a toilet flush, and then the sound of Lungile and Patience chatting.

Next to the master bedroom was a study with a charger cord snaking across the glass-topped desk, but no laptop. I opened the top drawer of the desk and found the new model MacBook, which joined the other loot in my bag.

‘Tatenda,’ Lungile said to Patience, thanking her as I joined them in the lounge room.

‘I think I’ve seen enough,’ I said. Lungile nodded and thanked Patience again, as did I. I said goodbye to the dog, ruffling him under his chin. ‘Look after your mom tonight,’ I whispered to him.

‘I will open the gate from in here,’ Patience said.

Lungile and I walked out, keeping our pace measured but brisk as we went to the Merc and climbed in. I started the car, and as we drove towards the gate it began to roll open. Lungile fished into my shoulder bag and grabbed a handful of treasure. The diamond stud earrings, gold necklaces and other clearly valuable bits and pieces from the jewellery box glittered in her hands.

‘Check,’ she said, holding it up.

I eased my foot off the accelerator as she let all of the jewellery slither back into the bag, save for one gorgeous piece set with the biggest rocks I had seen in a long time. ‘Wedding ring,’ I said. I felt nauseous, the shame bubbling up inside me and fighting to come out. I swallowed.

Lungile nodded.

‘Shit. She probably leaves it at home when she goes out shopping because of bloody crime.’

‘Ironic.’ Lungile laughed, but I hadn’t meant it as a joke. I was almost at the gate when it stopped moving, halfway, then changed direction and began closing. Lungile looked back over her shoulder. ‘She must be onto us!’

‘Fuck!’ I accelerated.

Lungile was looking out the back window. ‘We’re not going to make it. The maid’s probably calling the armed response guys now!’ The panic rose up inside me, but I could not stop the car. We would be trapped. I had a pistol in the bottom of my bag, a puny little .32. It was for self-defence, ironically, against carjackers and other criminals. I had never, and repeatedly promised Lungile and myself that I would never, use a gun in the commission of one of our crimes. I hated myself enough for what I was doing, and I would rather be arrested than harm one of my targets or a policeman.

‘Give me the gun,’ Lungile said.

‘No.’ I snatched the bag from between us and put it under my legs.

I braced myself for the coming impact. The nose of the Mercedes made it through, but the gate closed on my side of the car. Metal on metal made a maddening screech as the whole right side of the sports car fought against the closing barrier. I revved the accelerator hard, fighting for our escape, and we squealed through, suddenly released like a champagne cork. I slammed on the brakes.

Lungile was wide-eyed. ‘What are you doing?’

‘Give me the wedding ring.’

She closed her fist around it and glared at me. But either she softened or she realised we were not leaving until she gave it to me, because she opened her fingers and I plucked it from her palm.

I could see through the mangled gate Patience was now running down the front steps of the mansion to check on our progress, mobile phone clamped to her ear as she yelled into it. There was a mailbox slot in the wall next to the intercom. I walked to it and popped the wedding ring through the slot then turned and ran back to the car.

I put my seatbelt on and stood on the accelerator, sliding the rear of the car out into a right-hand turn. I zoomed up the quiet, leafy street, the engine howling as the automatic gearbox screamed and propelled us up to one hundred and thirty. When I took the next right I eased off a bit. I didn’t want to draw unnecessary attention to us, but I knew the bare metal scrape marks down the side of the car would be an instant giveaway once Patience or the Forsyths’ security company put the word out.

‘Taxi,’ Lungile said.

Ahead of us a minibus taxi had pulled over to pick up a gardener in green overalls, his work finished in some rich family’s home. I passed it then pulled over and we both got out. The taxi started moving again and Lungile stepped out onto the road and flagged it down.

I grabbed the bag of loot and went to her side. The driver stared at us incredulously; a black diamond and a kugelhailing him was probably a first. He leaned out of his window, looking Lungile over from head to toe. ‘Where to, sister?’

‘Anywhere but here,’ she said.

He looked at the banged-up car and grinned. ‘Climb aboard the love bus.’

Lungile and I squeezed our way in among the dozen domestic staff and the driver took off. I glanced back and saw flashing lights as a security company car rounded the bend behind us. As I continued to crane my neck I saw them slow and stop beside the Merc.

Lungile punched me on the shoulder. ‘Man, that was close.’ She laughed.

‘Too close.’

Hip-hop thumped from speakers in the roof above us, the beat not keeping pace with my heart.

3

Hudson Brand woke an hour before dawn, as he always did. As a safari guide his working day typically began at first light, or just before. This was the time of day when the predators – lion, leopard, hyena and so forth – were most likely to be on the move, finishing their night’s hunting or making use of the cool hours of light to have one more go at killing something.

Before the first tourists rose, however, there was work to be done. In some camps he had guests to wake, doubling as a waiter cum personal valet and delivering tea or coffee prepared by the kitchen hands. More than once he had crept out of a guest’s tent or chalet to quickly shower and don a fresh uniform before starting his predawn chores.