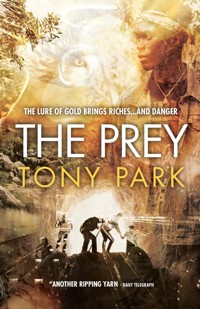

8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

In Africa, men - and women - will risk all for the lure of gold

Deep underground in the Eureka mine, South Africa’s zama zamas illegally hunt for gold. King of this brutal underworld is Wellington Shumba, a man who rules his illegal miners through fear of torture and death.

Running Eureka’s legitimate operation is former recce-commando Cameron McMurtrie. When one of his engineers is taken hostage, Cameron does not hesitate to mastermind a dramatic rescue – and finish it off with a manhunt for Wellington. That is until corporate interference from the mine’s Australian head office, in the shape of ambitious high-flyer Kylie Hamilton, gets in his way.

Kylie is visiting South Africa supposedly to finalise a new mine on the border of the famed Kruger National Park, but instead she and Cameron are forced into a partnership to fend off an environmental war above ground, and a deadly battle with a ruthless killer below.

Cameron and Kylie have become Wellington’s prey. They must unite – their lives depend on it.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

About The Prey

In Africa, men - and women - will risk all for the lure of gold

Deep underground in the Eureka mine, South Africa’s zama zamas illegally hunt for gold. King of this brutal underworld is Wellington Shumba, a man who rules his illegal miners through fear of torture and death.

Running Eureka’s legitimate operation is former recce-commando Cameron McMurtrie. When one of his engineers is taken hostage, Cameron does not hesitate to mastermind a dramatic rescue – and finish it off with a manhunt for Wellington. That is until corporate interference from the mine’s Australian head office, in the shape of ambitious high-flyer Kylie Hamilton, gets in his way.

Kylie is visiting South Africa supposedly to finalise a new mine on the border of the famed Kruger National Park, but instead she and Cameron are forced into a partnership to fend off an environmental war above ground, and a deadly battle with a ruthless killer below.

Cameron and Kylie have become Wellington’s prey. They must unite – their lives depend on it.

For Nicola

Contents

Authorís note

At the time of writing this book, in 2013, there was minerals exploration occurring in several national parks and wildlife areas in Africa. Contrary to the story you are about to read, however, there were no plans to develop mines in or adjacent to the Sabi Sand Game Reserve in South Africa, or in the coastal region of Inhambane or Homoine in Mozambique. The proposed coalmines mentioned in this book are completely fictitious.

Prologue

Australian Financial Review online

Mining executives killed in Zambian air crash

10 October 2013

Lusaka, Zambia: Troubled Australian mining giant Global Resources is mourning the loss of two of its brightest stars, second-in-charge Dr Kylie Hamilton, and a senior South African mine manager, Cameron McMurtrie, who died today in a light aircraft crash in Zambia.

Dr Hamilton, the company’s director of health, safety, environment and community, had been widely tipped to take over the company if and when its besieged CEO, Jan Stein, departed. Dr Hamilton and Mr McMurtrie, who had been recently appointed to the position of director of new projects, were on their way to visit a mine in Zambia’s copper belt region when their Cessna crashed.

A Zambian air force helicopter found the crash site yesterday in rugged bushland in the centre of the country’s remote Kafue National Park. Reports said the badly burnt bodies of two men, one believed to be the pilot, and a woman were found at the scene of the crash.

Mr McMurtrie, from Barberton, South Africa, and Dr Hamilton, from Sydney, Australia, were the only two passengers on the flight.

‘The pilot did not radio a distress call, and a ranger in Kafue National Park told us he saw the aircraft pass overhead and then heard a loud explosion a short time later,’ Zambian military spokesman Colonel Oliver Mwanzi told the Australian Financial Review.

Mr Stein said in a statement issued last night that Dr Hamilton and Mr McMurtrie were irreplaceable members of the Global Resources family.

The news has sent Global Resources shares plummeting to an all-time low, continuing the trend of the last two weeks as the company has lurched from one crisis to another in its African operations.

PART ONE

1

Sabi Sand Game Reserve, Mpumalanga, South Africa

Unlike the rest of his kind, he was a catcher of fish, and unlike those of his relatives who also liked to fish, he did so at night.

He didn’t fear the darkness, populated as it was with the lion and the leopard on the hunt and countless smaller predators, such as the wild cat, the serval, the genet and the civet. Secrecy was part of his defence. He was a master of camouflage and, although he had a big voice when it was called for, he usually went about his business in silence.

He scanned the water of the Sabie River in front of him. It was the end of the long dry winter and the river, which had been a raging torrent that claimed trees and washed away banks in the summer, was now gurgling gently. Perfect.

His eyesight was good. In the light of the full moon he could see a fat barbel snaking its way along the bottom, its ugly black tadpole-shaped bulk and its cat’s whiskers clearly silhouetted against the rich gold of the sandy bottom of the shallow river.

A crocodile cruised a little further upriver, its nostrils and eyes the only parts of it that sliced the glittering surface. A hippo honked its impatience at another in its pod as it wallowed and queued, waiting for its turn to wade ponderously out of the river and begin a night of foraging for grass.

The deep shade of the sycamore fig cloaked the fisherman in a dappled moon shadow, so the barbel wouldn’t see him until the second he speared the water and struck. He watched the fish and thought of the feast to come.

From the home he shared with his mate he heard the cry of his baby. He turned his head three hundred and sixty degrees to face the sound.

His baby squawked again. A fiery-necked nightjar offered a prayer to the night: good Lord, deliver us, good Lord, deliver us, the bird called.

He was under pressure.

A blade of bright light suddenly slashed the darkness and played across the surface of the Sabie River. The barbel, as startled as the fisherman by the intrusion, flicked his tail and disappeared upriver at a speed surprising for his size. The crocodile dived, like a sub-marine preparing for action.

‘Look, it’s an owl,’ a human voice called.

The fisherman took flight.

2

Barberton, South Africa

Chris Loubser hated the dark. He stole a last glimpse of daylight as he walked into the cage, and closed his eyes tight as the gate slid shut. The few people in his personal life who knew of his phobia – his sister and his parents – had been astounded when he’d taken the job working underground.

The cage bell rang. Immediately it felt to him as though the rock walls around him had started to move inwards, as if pushing the bodies of the other mine workers into him, so that he melded with them, a single multi-armed, multi-legged crush of flesh sandwiched between the pressing rock.

This was his nightmare, and his job. Themba, his newly recruited and freshly university-minted assistant, elbowed him in the ribs. Chris, startled, opened his eyes to see the young man grinning. He’d said something but Chris hadn’t heard it over the screaming of the spooling cable.

‘What?’

‘It’s faster than I thought. Hell of a ride, man.’

Chris nodded and took in the scene in front of him. Themba seemed to be enjoying it. Two other men in the cage chatted and laughed casually, and another couple stared straight ahead, looking bored. Just another shift. Chris wished he could be like them.

‘It’s a job, Mom,’ he’d said to his mother. ‘And I’m a twenty-nine-year-old Afrikaner oke in a workforce where black women are at the top of the hiring list – even in the mines – and white men are at the bottom.’

‘You could go to Australia, Chris, there’s plenty of work for smart boys like you there.’

His mother hadn’t looked into emigrating, but Chris had. He knew it wasn’t nearly as easy for him to enter Australia as she thought, and besides, the only industry that would offer him a job and sponsor him into the country was mining. If he was going to have to work in an underground hell he would rather it be at home. He loved the bush and he loved his country, despite all of its faults.

‘I can do more here in South Africa,’ he had told his mother. ‘In Australia safety is already the industry’s priority, whereas here there’s much more to be done on that front. I can achieve more here. I can save lives, Mom.’

His stomach lurched as the multi-deck cage he was riding hurtled into the black abyss. Suspended below the platform he stood on were two more decks, each with a further six people in them.

He knew the statistics, and they didn’t make him feel better. The temperature rose by 0.4 of a degree for every hundred metres they descended. He’d checked the thermometer before entering the cage and worked out that the wet-bulb temperature would be 30 degrees – flipping hot – in the madala side they were heading to, one thousand, four hundred metres below ground level.

‘You feeling OK, man?’ asked his dreadlocked trainee.

Chris looked beyond the confines of the cage and saw the rock face rushing past. He wished he’d kept his eyes shut. ‘Big night last night,’ he responded weakly.

Themba threw back his head and laughed. ‘I thought you were the quiet one in the office?’

Chris supposed he was. He hadn’t been out drinking last night; he had been poring over the environmental impact assessment for a new mine, the one planned for the game reserve. He was one of six people in the South African office of Global Resources who’d been asked to contribute to the assessment when it was in draft form. Most of his comments had been included, some ignored.

Chris closed his eyes again. The truth was he spent very little time underground, but Themba had never been into a madala side and it was company policy that no one went into the disused tunnels, or an ‘old’ side or area as the name meant in English, alone. It was too risky. They were also being escorted by a mine security guard, an Angolan named Paulo Barrica, who carried an R5 assault rifle in addition to his lamp and the self-rescue pack they all wore underground.

The smell and heat of the bodies around him added to Chris’s sense of unease, a feeling that was rising steadily with every additional level they plummeted. Nearly a kilometre and a half, he thought to himself. It would have been worse if he was working in one of the big goldmines in the Free State; some of them were more than three thousand metres deep. He clasped his hands together to stop them from shaking. He couldn’t let Themba see just how frightened he was.

When the hoist driver stopped Chris and Themba’s deck at level fourteen, bells rang to tell the onsetter controlling the cage it was safe to open the gate. The man nodded for them to get out. Barrica knew the way to the disused workings and he led off, his rifle cradled across his broad chest.

‘Who were you out partying with last night – some of the boys from the office?’ Themba asked him. ‘Get in trouble from the wife?’

‘No. I’m not married.’

‘I am. We have a little girl, just turned six months. Do you have a girlfriend?’

‘No,’ Chris said.

Chris wondered if Themba was making small talk because he sensed that Chris was nervous and was trying to ease the tension. If so, it wasn’t working. He wanted to be alone with his thoughts and fears.

They left the parade of men and machinery behind them as the three of them turned into an unlit side tunnel. Barrica turned on his lamp and Chris and Themba followed suit.

‘This leads to one of the madala sides,’ Chris said. In front of them, in the light cast by Barrica’s lamp, they could see where the tunnel had been bricked closed, and where a man-sized steel door had been fitted at the wall’s centre. Barrica unclipped a key chain from his belt, set down his R5 against a wall and tried three keys before he found the one that opened the padlock on the latch.

‘Although this part of the mine isn’t being worked it still needs to be monitored,’ Chris said, more to stop himself from turning and running back to the cage and begging to be hoisted back to the surface, than from any real need to explain to Themba why they were here.

‘Because of the dead zama zamas?’ Themba asked. ‘Why do we even care about them?’

Chris didn’t bother to hide his annoyance. ‘Because our men work nearby. We know some of the bodies the zama zamas leave out for us to collect died of cholera and others from carbon monoxide poisoning. Cameron wants us to find out how close the contaminants are to our workers.’ He risked adding, ‘And because they’re human beings.’ The term meant ‘try try’ or to chance, and Chris despaired at the poverty or greed that would make men want to live likes a zama zama, slaving away for months on end underground, where death was a more likely outcome than riches.

‘You sure we’re safe down here then, man?’

Chris stopped and turned to Themba. The younger man took half a pace back. Chris saw he carried his own fears. ‘You’re worried about the zama zamas?’

‘No.’ He shrugged his shoulders. ‘Well maybe.’

‘That’s why Paulo’s here,’ Chris said, nodding towards Barrica’s broad back. The security guard now held his rifle at the ready, the tip of the barrel leading the way. He didn’t bother looking back at them. Paulo had been hired because of his military skills – he was a veteran of years of fighting in the Angolan civil war – and because as a foreigner there was less risk of him being bribed or coerced into working for the local zama zamas. He would also have no qualms about killing them if he had to.

‘Come on then,’ Chris beckoned Themba with false bravado. ‘We’ve got work to do.’

As they trudged behind Barrica in the subterranean heat, Chris was sweating and a little short of breath. He stumbled every now and then as his gumboots slipped on an irregular chunk of rock. As they rounded a bend, he smelled something.

Barrica stopped and held up a hand. Chris gave Barrica a nod, and the Angolan started moving forward again, at a careful pace, rifle at the ready.

‘Eish! What is that stink?’ Themba put a hand over his mouth and coughed.

The rank odour grew stronger as they moved down the tunnel. Chris forgot his fears of the roof of rock falling on him, or of the side walls closing in on him. There was something very real waiting for them in the blackness ahead. The stench reached out for them.

‘What is that?’ Themba asked again.

Barrica stopped and turned to fix the young man with the hard stare of a warrior. ‘Ssssh. That smell, it is death.’

Sydney, Australia

Kylie set down her takeaway latte on the boardroom table and looked into the lens of the video camera.

‘OK, please tell us your name and position in the company as a tape identification and sound check,’ said the thin man operating the camera. ‘And look at me, not into the lens.’

She shifted her gaze. ‘Doctor Kylie Hamilton, EGM, HSEC for GR.’ She’d been interviewed a few times for real, for mining industry magazines, some country newspapers in the Hunter Valley where she had managed a coalmine for five years, and twice for regional television. Kylie wasn’t nervous about the media training course she’d been volunteered for by corporate affairs, but given the choice she would have been back at her desk – she had a mountain of work to get through before her flight to South Africa the following morning.

‘EGM HSEC?’ The media trainer smiled condescendingly. ‘GR?’

‘Executive General Manager, Health, Safety, Environment and Community, Global Resources,’ Kylie said with the patience of a teacher taking extra time for the slow learner.

‘Window-dressing, in other words.’

Kylie sighed inwardly. So this was how it was going to be. There were three other people on the course, her CEO, Jan Stein; the human resources EGM, Jeff Curtis; and the new South African corporate affairs manager, Musa Mabunda, who was in Australia for four days of familiarisation with the business. Out of the corner of her eye she saw Musa put his hand over his mouth to hide his customary smile. Let him smile. ‘I wouldn’t say window-dressing, I’d say –’

‘Environment?’ the thin man said over the top of her. ‘How environmentally friendly is a company that destroys the pristine bushland of the Kruger National Park, South Africa’s flagship game reserve?’

‘I’d say we’re very friendly. The land we’ve been exploring on is hardly pristine and –’

‘The land you’ve been exploring,’ the trainer paused for a moment to check his notes and Kylie was about to jump back in and finish her sentence when he silenced her again, ‘is home to a denning site of the endangered African painted dog, as well as black rhino, cheetah, lion, leopard, and a host of other threatened animals.’

‘Actually, it’s –’

‘Why is Global Resources raping South Africa’s iconic national park?’

Kylie was getting annoyed at the trainer. She knew it was only role-play and she had been in more stressful situations before – both in training and in real life – but she suspected he was going harder than was useful, possibly because she was the only woman in the room and on the exec team. ‘We’re not raping anything. If I could just finish what I was –’

‘Yours is the same mining company that’s recently been exploring in other parts of Africa, isn’t it? How much does Global Resources expect to make off the backs of poorly paid African workers this year?’

‘Our mines in South Africa were spared the strikes and violence that plagued other operations in that country last year because our workforce is treated with respect and we have negotiated mutually agreeable pay packages with our people.’ Finally, she thought, she was getting it together. She added: ‘Our financial position is particularly strong given the demand for resources in developing countries.’

The interviewer nodded. ‘Yes, and China and India’s hunger is going to cost South Africa one of its great wilderness areas.’

‘You’re putting words in my mouth,’ she said. He smirked at her and she felt like punching him in the face. She could feel the sweat pricking at her armpits and beading on her top lip. She’d stared down unionists over enterprise agreements, green activists over open-cut mines, and politicians over the mining tax, but those were real negotiations, where Kylie had at least been treated with respect, even if her views weren’t popular. Kylie was also conscious that her boss and the rest of the exec team were watching her, like Roman spectators at a one-sided gladiatorial contest.

‘How safe are Global Resources’ mines?’ the trainer asked, changing tack just as she was formulating something to say about profits and demand for minerals worldwide.

She reached for a lifeline. ‘I’m pleased you asked,’ she said, smiling. ‘Our mines are very safe. Safety is our number one priority.’

‘In Australia perhaps, but what about Africa? Isn’t it true, Ms Hamilton, that nine workers were killed in workplace accidents in South African mines last year?’

She stared at him.

‘Well?’

He trotted out his make-believe questions like he was some hotshot investigative reporter, but the truth was he hadn’t worked as a journalist for years. Kylie, on the other hand, had seen what was left of a man when his remains were dug from the cab of a truck that had just had five tonnes of coal dumped on it by mistake. This was bullshit.

‘Ten,’ she said.

‘Sorry?’ said the trainer.

‘Regrettably, ten people were killed in our coal and goldmines last year, not nine, and that is ten too many.’ She paused. ‘And it’s Doctor Hamilton, if you don’t mind.’

The man glanced at his notes, then looked up at her, this time meeting her eyes for the first time. ‘Thanks for your time.’

Kylie unclipped the microphone from the lapel of her jacket, picked up her now lukewarm coffee, stood up and went back to her seat.

The trainer rubbed his hands together. ‘Next victim.’

Kylie had volunteered to go first but now Jan Stein and Jeff Curtis looked at each other. They’d just seen her demolished on camera by a one-man wrecking ball and neither wanted to go next. Kylie thought Jan would have had bigger balls. She opened the workbook the trainer had given each of them; as a senior member of the team she would be required to face the media more often and now that the shock of the pretend interview was over she was looking forward to mastering a new skill. If she had a chance at a second interview, and she suspected this would be part of the training, Kylie wanted to be able to nail it. She had not got to where she was in this male-dominated industry by backing down from confrontational situations.

‘My turn,’ said Musa. He was beaming. Kylie looked up from the course notes as Musa got up, adjusted his silk tie and buttoned his suit jacket. He was the smartest dressed man in a head office full of suits – some of them very expensive. By contrast, Kylie’s approach to her wardrobe could be described as pragmatic at best. While she had an office in the company’s Sydney headquarters, in Macquarie Street with a view out over the Botanic Gardens to the Heads, she spent most of her time on the road and on-site at the company’s mines. There she wore steel-capped boots not stilettos, and the standard uniform of blue overalls with a yellow high-visibility vest ringed with reflective panels – a uniform she felt far more comfortable in than the navy A-line skirt suit she’d thrown on for today’s training session.

Musa took a seat in front of the trainer, threaded the lapel microphone up under his jacket and carefully attached it to his perfectly tailored grey suit jacket. Kylie felt sorry for the man already, he was about to be eaten alive.

‘OK,’ said the trainer, ‘we’re rolling. If I could just start by getting your name and –’

‘My name is Musa Mabunda,’ he spelled in a clear, deep voice, his delivery slow and precise, yet not laborious. ‘I am the Manager of Corporate Communications for Global Resources in South Africa.’

‘Mr Mabunda, how can your company rape –’

‘Perhaps I could start by giving you an overview of our plans for a new mine in South Africa – a mine that will uplift an impoverished community, provide valuable resources and income which will aid the development of the new South Africa and be a world-class model for safety and environmental protection.’

The trainer tried to interject, but Musa had the ball and he was running with it. Kylie smiled. The former journalist tried again to ask one of his barbed questions, but Musa raised his voice ever so slightly and continued his monologue.

‘First, the site of the proposed new Global Resources coal extraction facility is not, I repeat, not in the Kruger National Park. It lies to the west of the park on a former game farm that was returned to its rightful owners, the Shangaan people, back in 2009. The traditional owners of this land own the mining rights, not the national parks board of South Africa.

‘This proposal has been the subject of an exhaustive environmental impact statement and Global Resources has not only met, but in fact has exceeded the requirements placed on the company by government in terms of air and water quality management, economic upliftment of local communities and wildlife conservation conditions.’

‘But –’ tried the trainer.

‘Further,’ Musa continued, ‘this project will employ nine hundred formerly disadvantaged South Africans.’

The trainer looked at his notes. ‘There were ten fatalities in South African mines last year. What guarantees can you give that –’

‘As a company, safety is our number one priority and I can assure you that Global Resources works tirelessly to educate our workforce and to continually review our operations in order to improve this part of our business and ensure our people go home from work at the end of each shift as fit and well as they started.’

Kylie was impressed by Musa’s performance, but as the corporate PR man, this was his bread and butter. She had paid careful attention to the way he had steered the interview away from the trainer’s inflammatory line of questioning and back to the company’s key messages. She looked over to her CEO, Jan Stein, and saw that he was grinning broadly.

‘Well, I think we’re done here,’ said the trainer.

Musa unclipped his microphone and stood up. Jan, the naturalised Australian from South Africa, started to applaud. Jeff and Kylie joined in. It was all bullshit, Kylie thought, but it was damn good bullshit. Musa winked at her as he took his seat beside her.

3

‘Zama zama,’ said Barrica, as his headlamp played over the body at his feet. Themba was dry-retching, having just thrown up his breakfast.

Chris held his hand over his mouth and played his lamp across the dead man. Decomposition accelerated underground, aided as it was by the heat. The corpse was so swollen that the dead man’s tattered and threadbare overalls had started to split. His mouth was stretched in an obscene grin and his fingers were like plump black sausages.

Chris composed himself, then looked over to Barrica. ‘Ja. But odd they didn’t leave him somewhere easier for us to find him like they usually do. They couldn’t have known we’d be inspecting this site any time soon.’

Themba looked up. ‘What do you mean?’ he asked.

Chris explained that the zama zamas, the pirate miners who worked the madala side as industriously – sometimes more so – than Global Resources’ legitimate employees, often suffered workplace fatalities, but usually the bodies were dragged to a working part of the mine, or even as far as the main shaft, so they could be found by the next GR shift and returned to the surface. No one wanted to work around decomposing corpses a kilometre and a half underground. Not even illegal miners.

‘What do they die of?’

Chris shrugged. ‘Everything. Accidents, exposure to harmful chemicals such as mercury in the extraction process, heat exhaustion, AIDS – and lately cholera and carbon monoxide poisoning. These guys live underground for weeks or even months at a time – many don’t survive.’

‘We need to get back and report this, baas,’ Barrica said, yet even as he spoke the words he was stepping around the body and heading deeper into the darkness.

‘What are you doing?’

Barrica held up a hand to silence Chris. He glanced back and put a finger on his lips and switched off his lamp. Chris immediately did the same, then reached out to Themba and switched his off too. ‘Shush,’ he said to the young man, and dragged him to the side wall of the tunnel and down to his knees.

‘What’s going on?’ Themba whispered.

‘Quiet.’ Chris felt the fear rising in him. Now their lamps were extinguished he could see a pale flicker of light further down the tunnel. It wasn’t as dark as it had seemed. There was someone down there. ‘Stay here,’ he whispered to Themba, and crawled towards Barrica.

He groped ahead of him and felt the big security guard start as his hand found his body. ‘You said it yourself, we need to get out of here,’ Chris whispered.

‘They are close,’ Barrica growled. ‘Listen.’

Chris heard the voices now, speaking in Portuguese. Mozambicans. In recent years the South African government and the unions had insisted that seventy per cent of a mine’s workers had to be South African citizens, and over time this had meant that many Mozambicans had lost their jobs and turned to illegal mining. Sometimes they returned as zama zamas to the same mines where they’d once held honest jobs.

Behind him, Chris heard footsteps, a stumble and a curse. Themba was making a run for it in the dark.

‘Ola!’ a voice called. Light flickered off the rock walls. The man was probably carrying a candle. Shit, he thought to himself, this was not going well.

His peripheral vision was suddenly lit up and Chris looked back to see that Themba had switched on his headlamp. It was bobbing away from them, the bright light bouncing off the side walls as he ran.

‘Fok, no,’ Chris cursed under his breath.

A series of explosions rang out, the crack and thump of passing bullets pounding Chris’s eardrums. He flattened himself onto the floor as sparks bounced off the walls and a muzzle flash seared his eyes. Someone was shooting at them, with an automatic weapon by the sound of it.

‘AK-47,’ Barrica said, his summation punctuated by a three-round burst from his own assault rifle. ‘Fall back!’

Chris needed no urging. He crawled on his hands and knees over the jagged floor of the tunnel, scrambling as fast as he could. The AK fired again and a stream of red-hot fireflies whizzed over his head. He was glad he’d stayed low. Themba, however, was still running, and Chris saw his lamp pitch to one side, then fall.

‘Themba!’ he screamed.

Barrica returned fire. ‘Run, check the young one. I will cover you,’ the security guard shouted out through the chaos.

Chris forced himself up and started to run on feet that felt encased in lead. He’d had a dream like this, where he was being chased by a man with a gun and he couldn’t make himself move fast enough. He tensed his muscles, waiting for the spear of pain in his back that would pitch him into the abyss of death. ‘Themba!’

His foot collided with something slightly yielding and he fell forward onto the rotting mass of the dead miner. He yelped as he scrambled to get up. Something popped and a hiss of foul-smelling gas jetted up into his face. He put his palm on an arm, or maybe it was a leg, and felt the putrid skin slide away from the body. Covered in slimy, stinking fluid he finally managed to stand. He stumbled a few more paces, got clear of the corpse and glanced back to see if Barrica was following him.

The guard’s R5 chattered again, silhouetting Barrica in flashes from the muzzle.

‘Grenade!’ Barrica shouted. He turned to Chris and started to run towards him. The homemade bomb, a stick of dynamite with a burning fuse in a can packed with nuts and bolts and screws to act as shrapnel, bounced on the floor of the tunnel behind Barrica and erupted. Barrica was blown forward, arms outstretched, as Chris was knocked off his feet and thrown onto his side. His ears rang and he felt like he’d been kicked and punched all over. He crawled towards a shard of light – from the door where they’d entered the chamber – and saw the beam of Themba’s light fixed horizontally across the floor from his helmet, which lay beside the young man. He covered a few more metres before he reached Themba, who was sprawled on the rock floor, face first, and placed his fingers on his neck. He couldn’t find a pulse. Chris half-rolled the fallen man and gagged. A bullet had drilled a hole in the back of his head, and the exit wound had ruined his once handsome face. Chris had feared death underground for so long – virtually every time he ventured below the earth’s surface – but it was not supposed to be like this.

‘Bastards!’ He tried to stand, but crumpled to one knee when his left ankle buckled. He started to hobble, but was knocked to the ground by something shoved into the small of his back.

Chris rolled over and squinted as a miner’s lamp was turned on and shone in his face. A man in overalls stood over him, pointing an AK-47 down at him. He smiled. ‘Bom dia, mister.’

*

Kylie had started to take the media training seriously after her initial humiliation by the trainer. She still didn’t like the man, nor the media, but she was fast gaining an appreciation of the skills she needed to master if she was going to be the public face of Global Resources. And she also had to ensure that she wasn’t perceived as the weak link in the management team. She’d fought too hard to get where she was to be defeated by a day-long PR course.

Jan had followed Musa into the trainer’s hot seat and while he hadn’t done nearly as good a job at getting his messages across and batting away difficult questions as Musa had, their chief executive had acquitted himself well. Certainly, Kylie knew, he’d done a better job than she had. Kylie was never happy coming second, not even to the boss. She would bring her A game when it was time for the second interview, which the trainer had told them would come at the end of the day.

As far as Kylie knew, no one had mentioned to the trainer that the reason she was here was because Jan had told her he wanted her to take over those media interviews he would normally handle. When Jan had poached her from a competitor five years earlier, he’d been full of promises about the amazing opportunities ahead of her. But in the first few years her career had stagnated and she had spent three years longer than she wanted to managing the sustainability division when she really wanted to be at the coalface – and to join the executive team. Finally, a month ago, Jan had given her the EGM position she should have gotten years earlier. She was glad she’d stuck with it, but now she knew the pressure was on – she had to prove to the others that Jan was right to promote her. She had to prove it to Jan, too. And she had to prove it to herself.

‘Do you think the gender of the potential spokesperson has any bearing on how the journalist will conduct the interview?’ she interjected.

The trainer swung in his chair to look at her, and gave a little smile. ‘Since I don’t work for Global Resources I don’t feel the need to be particularly politically correct in answering this question. So I’ll say yes, it does.’

‘What do you mean by that?’ Jan asked.

‘I mean that Kylie here would be a perfect spokesperson for your company. She’s female and attractive – definitely not what your average journalist or Joe Blow thinks of when they try to picture a miner.’

‘OK,’ Kylie said, ‘but don’t you think the journalist would see this for what it is – using a woman to try and soften the image of a company that’s copping a lot of flak in the press?’

‘Yes, they will, and it may make the tone and the line of questioning even harder, particularly if it’s another woman interviewing you.’

Kylie folded her arms. ‘So you don’t think it’s a good idea. You’re saying a journalist may be straighter with a man representing a mining company.’

‘What I’m saying is that there are some who will try their damnedest to expose your being wheeled out to face the cameras for the cynical tokenism that it probably is.’ He paused. ‘Just being honest,’ he added.

Kylie looked at Jan. He was straight-faced. She’d just been utterly undermined by an outsider, yet Jan remained silent. Not for the first time, she wondered whether he truly believed in her, or if he had only wanted her to do more media work because she was a woman and he thought that might soften Global Resources’ image during a tough time.

Jan put his fingertips together and rocked back in his chair. They all looked at him. ‘Not that it’s any of your business,’ he said, looking first to the trainer and then to Kylie, ‘but there were three people in line for the Executive General Manager role. When I interviewed all of them I told each of the candidates that part of the duties of the EGM would be to engage with the media and progressively take on more and more of the media interviews that I’ve been doing as a matter of course. I don’t think I’m particularly adept at dealing with the media, and neither do some of our shareholders. The two men who were in line for the position – a significant promotion I might add – both said they wouldn’t be comfortable dealing with the media on areas outside their direct area of expertise. In short, Kylie here was the only person with the gumption to take on this job.’

Kylie smiled at him. Jan had been put on the spot, and he’d done what he always did best – set everyone back on their butts and reminded them why he was the boss.

Kylie’s BlackBerry was sitting on the boardroom table. It vibrated. From the corner of her eye she saw Jan and Musa both reach into their shirt pockets. She and Jan exchanged a glance. Group messages usually meant one thing. Trouble.

Jan scrolled through the message and looked at Kylie. She’d already read it. ‘Two dead, one missing,’ she said.

‘This is the last thing we need right now in South Africa,’ Musa said.

‘It’s the last thing we need any time, anywhere, Musa,’ Jan said.

‘Of course.’ He looked chastised.

‘You’re right, though,’ Jan nodded, ‘it couldn’t have come at a worse time with the South African press baying for our blood over the new mine.’

‘Should we take a break now?’ the trainer asked.

‘No.’ Jan fixed him with his grey eyes. ‘You can really earn your money now by preparing Kylie and Musa to face the media on a real-time critical issue. We’ve just had a security guard and a graduate trainee environmental officer killed in a gunfight underground in our goldmine in South Africa. A third man is missing. The people responsible are what we call zama zamas – illegal miners, sometimes referred to as pirates. They’ve taken hostages before, so it’s possible they’ll ransom the missing man, Chris Loubser.’

‘Shit, it doesn’t get more critical than that,’ the trainer said.

Musa looked at the ceiling. ‘Welcome to my world.’

Jan picked up the phone on the boardroom table and called his personal assistant, Margaret Lamont. ‘Mags, I need you to set up a video call with Cameron McMurtrie in South Africa.’

Jan hung up. ‘So, Kylie, given you’re halfway through your first media training session and only a few weeks into the job, what do we say to the media about this one?’

She’d been making notes while Jan had been on the phone. She’d flicked through the trainer’s handbook and checked some other notes she’d taken while he’d been speaking. She took a deep breath. ‘We need to give the immutable facts of the incident – who, what, where and when, if not why. We don’t know why the zama zamas would have killed these guys. I’m assuming the security guard would have been armed, but if our environmental manager and his sidekick were down there it doesn’t sound like our guys were looking for a fight. We need to express remorse for the loss of our people and condolences to their families and position Global Resources as the innocent victim of criminal activity. Our number one priority is getting this guy, Chris –’

‘Loubser,’ Musa prompted.

‘Right, getting Chris Loubser back alive and making sure these pirates are brought to justice.’

Jan leaned back in his swivel chair again while he thought for three seconds. ‘Mister media expert, what do you think?’

‘I think Kylie’s been paying attention during her training today,’ the trainer said.

‘I felt I had to after you humiliated me at the beginning of the session,’ she said.

‘Don’t blame him,’ Jan said. ‘The real media are going to be a lot tougher on you, and it won’t end with this terrible incident. Next, you’re going to have to sell South Africa on the idea of a new mine being opened on the doorstep of the country’s favourite national park.’

There was a knock on the door and Margaret came in. She nodded greetings to them all. Mags was twenty-five and looked a picture of innocence with her blonde curls, but Kylie knew from personal experience she guarded Jan and his diary like a Rottweiler.

Mags turned on the widescreen plasma TV monitor mounted on the wall and sat at the table and dialled on a desktop console.

The screen came to life and they saw a utilitarian meeting room. The decoration on the miners’ wall consisted of whiteboards covered in targets and plans. The only man in the room sat at a circular timber laminate table and was leaning forward, fiddling with the monitor he was looking into.

‘Howzit, boss,’ Cameron McMurtrie said. He wore overalls with the Global Resources logo embroidered above the breast pocket.

‘Fine thanks, Cameron. Sorry to be talking to you for this reason, and sorry for the loss of your men.’

‘Thanks boss.’ Cameron held out a personnel file at arm’s length so he could read something and Kylie recognised the sign of someone who would soon need reading glasses. Men could be quite vain about such things, she knew. ‘Themba Tshabalala was a new guy and I didn’t know him well, but old Paulo Barrica was a good oke and straight as can be.’

Kylie had never met Cameron McMurtrie in person but had seen him in a couple of video conferences. His eyes were red-rimmed and his face and shirt were smeared with dirt. She guessed he’d already been down to the scene of the killings and hadn’t yet taken the time to shower.

‘Do you think that was a factor in what happened?’

‘Barrica’s honesty?’ Cameron shrugged. ‘Maybe. If I had more security guards like Paulo, these bloody zama zamas would find it a lot harder to stay in business. The truth is that some of my guards are directly involved in letting the pirates in and out, or getting food down the mine and gold out, and others would probably turn a blind eye to the smuggling. Barrica had the guts to come to me a couple of times and tell me when stuff was being moved down the mine, and we were able to confiscate a lot of contraband – food, drugs, booze, tools, the sorts of thing the pirates need to stay in business. He would have made some enemies so, yes, I guess it could have been a set-up to kill him, but I didn’t think the zama zamas would be stupid enough to try and take out two environmental guys at the same time.’

Jan nodded, and looked at Kylie.

She’d made some more notes, and she looked up from them to the camera mounted at the top of the screen they were watching. ‘Cameron, what do you know about Chris Loubser?’

Cameron rubbed his chin. ‘Howzit, Kylie. He’s very good at his job; sometimes too good. He’ll get me to stop operations if he sees something or his monitoring tells him something’s not right. He’s a stickler for the regulations and safety, which is how it should be, even if he can be a pain in the arse, you know?’

She nodded, although she wanted to tell him that safety really was a priority and not a pain the arse. She held her tongue, though, as an argument was not what any of them needed right now.

‘Also, between us, Chris doesn’t like being underground. He’s never said anything but I’ve been down with him and I can tell when a man doesn’t want to be there. It’s not for everyone and it doesn’t stop him doing his job, but I’m worried about him if he’s alive and maybe hurt down there with those bastards.’

‘So we need to act quickly,’ Jan said.

‘The guys are pissed off by this attack, boss.’ Cameron’s hands, visible on the tabletop, balled into fists. Kylie saw his eyes harden as he leaned closer to the camera. ‘I’m putting together a team to go down there and get Chris out.’

‘Shouldn’t you wait for the police?’ Kylie asked.

‘I don’t know what state Chris is in – there was blood all through the madala side. Besides, my guys know the mine and the zama zamas better than the police do. They’re ready to moer the bastards.’

Kylie guessed moer meant something bad. ‘I’m worried about more of our employees getting injured. Have you called the police?’

Cameron shook his head. ‘Kylie, with respect, this is Africa. The police don’t want to get involved because they’re not experienced in working underground. Plus, we think the local commander is being paid off by the illegal miners. We have to do our own dirty work.’

‘Global Resources can’t be a party to vigilante action and –’

‘Boss,’ Cameron pointedly turned away from Kylie, ‘you know what needs to be done and you know we can sort this out ourselves.’

Jan leaned back in his chair, bringing his hands together and to his lips as he always did when he was thinking. He nodded, but said: ‘Kylie’s right on this one, on both counts, Cameron. This isn’t the old days. There’s a crime scene underground and the police are going to have to be called in. I also agree that the last thing we want now is any more of our people hurt as a result of this thing. Let’s all take a deep breath.’

Cameron rubbed his forehead with the thumb and forefinger of his right hand. ‘Ja, all right, boss, but the guys won’t like us doing nothing. The union’s going to bliksem us over this as well. COSATU’s already gone on record as opposing the new coalmine in the game reserve, and there’s the ongoing agitation over workplace deaths in the mines.’

‘But it’s not a game reserve,’ Kylie said. ‘If we’re using incorrect terminology in private it will spill out into the open arena. That land is privately owned by the local people, it’s no longer part of the Sabi Sand Game Reserve.’

Cameron snorted. ‘Tell that to the animals that live there, Kylie.’

‘Enough, Cameron,’ Jan said. ‘Kylie’s right. We need to stick to the facts. Our priority now is to get this mess sorted, and that man out alive. Kylie, when are you due to fly out?’

‘Tomorrow morning, boss. On the Sydney–Joburg direct flight.’

‘You’re still coming over here?’ Cameron eyeballed her.

‘Why wouldn’t I?’ Kylie said, quicker than she’d meant.

‘You’ll be walking into a shit storm,’ Cameron said. ‘If you thought pitching the new mine was going to be tough, then it just got a lot worse.’

‘I’m not the sort of person who backs down from a challenge,’ Kylie spat back.

‘OK,’ Jan placed his palms down on the table with enough force to silence Cameron and Kylie. ‘Enough. Two of our men are dead and their families must be cared for, and another of our colleagues is missing. Kylie, change of plans – get Mags to book you on tonight’s flight via Perth. That will put you on the ground a working day earlier. Use the time between now and when you arrive in South Africa to thoroughly ground yourself in our operations and business there. Cameron, if you lead some maverick rescue operation without my approval I’ll have your balls as a paperweight. The South African media went into a frenzy last time a mine security contractor slotted a bunch of zama zamas. We don’t need any more bad press. Understood?’

‘All right, boss.’ Cameron looked at his watch. ‘If there’s nothing more to discuss, I have to contact the dead men’s families and call Chris Loubser’s parents again.’

‘Good luck,’ Jan said, and indicated to Mags to terminate the video conference. He turned to the media trainer. ‘Give Kylie the toughest time imaginable – it’s going to be far worse for her in Africa.’

4

Tertia Venter zipped up her green polar fleece with the lion’s head logo embroidered above the left breast. It was going to be another perfect sunny September day in the lowveld, but the mornings were still nippy.

‘Morning, my boy,’ she said to the old bull elephant they called Marula, who was peeling the bark from a tree with his left tusk, his remaining good one, fifty metres from her house. Tertia got into the old open-topped Land Rover Defender and turned the key. The vehicle, Old Smokey, was like her – not a creature of the morning. Eventually it started.

She drove along her gravel driveway out onto the rutted road that led from the deliveries gate to the back of the main lodge. It wasn’t far, not even a kilometre, but hunting lions had been seen between her house and the lodge the night before, according to her head guide, Tumi Mabunda.

Tertia shifted down to first gear as she drove down the bank of the dry riverbed, then selected diff lock as she hit the sand. She gunned the diesel engine and looked left and right in case the resident leopard was in one of his favourite trees. No luck. It was cold in the riverbed, a few skerricks of early morning mist still visible in the air, but the temperature rose as soon as she climbed out of the low-lying area.

The grass on the plain that gave the lodge its name – Lion Plains – was golden yellow and she scanned it for the tuft of Big Boy’s tail, but the old pride male was not out marking his territory this morning. Perhaps his lionesses had killed in the night and he was there now, muscling in for the good bits while his ladies and his cubs waited none too patiently. She hoped something was going right for someone or something this morning. Her time was running out.

She’d done this drive almost every day for the past eleven years. It had been her dream come true; hers and her ex-husband, Karl’s.

Staying on had been worth it; she’d wanted to live here since she was a child. The property, now called Lion Plains, had been bought by her grandparents as marginal cattle-farming land, infested with remnant wildlife, in the forties. They had hunted game on the property, known then as Sunnydale, and their children and grandchildren had spent family holidays on this wild tract of bushveld and golden grass. In the early sixties, her grandparents had joined with other local landowners to create the Sabi Sand Game Reserve, dropping fences between their properties to allow wildlife the freedom to move. Unlike on many of the other farms, there hadn’t been enough money in their family to develop a lodge or luxury camp for tourists or hunters. Tertia’s grandfather had been a better farmer than he was investor and a series of his get-rich-quick schemes had gone belly up. When he died from a heart attack, Tertia’s grandmother and parents had wanted to sell Sunnydale.

Tertia, however, had an eye on the future. It was the early nineties and change was coming to South Africa. Many whites feared a bloodbath if Nelson Mandela and the ANC eventually took power, but Tertia predicted – correctly, as it turned out – that Mandela would oversee a peaceful transition and that the foreign tourists who had boycotted her country during the years of apartheid, would one day be drawn to reserves such as Sabi Sand in droves.

Her father was doubtful and her siblings more interested in studying subjects that would lead to careers abroad, but Tertia’s mother encouraged her to look further into the viability of the idea of building a luxury tented camp on Sunnydale.

She met Karl when she was at university and fell in love with him. When she graduated, her father begrudgingly agreed to invest in Tertia’s plan to breathe new life into Sunnydale, which Tertia immediately renamed Lion Plains. Karl’s work kept them apart in the first year, but he always maintained a strong interest in the game farm.

When Karl managed to get time off and make it to the farm, they had the place to themselves, living in a safari tent, with a caretaker to keep the donkey boiler stoked to provide hot water, and the man’s wife to wash the clothes.

By the time change came to her troubled South Africa, with Nelson Mandela’s election as president in 1994, Tertia found herself in an empty house, with no husband. Karl had left her for a new life in a new country.

After both her parents were killed in a car accident, she and her siblings sold the family home in upmarket Rosebank and Tertia invested her share of the inheritance in building the accommodation units on the farm and renovating the old farmhouse as the main lodge and dining and entertainment area. With her parents taken from her in tragic circumstances and her husband gone, Tertia had poured her fortune, her tears and her wounded heart into the lodge.

The building gleamed the colour of an elephant’s ivory, newly washed in an African stream. Tertia pulled up to the office, located behind the souvenir shop, and got out of the Land Rover.

Tertia had had Lion Plains up and running in time to catch a wave of overseas tourist interest in South Africa. She’d put her business degree and her brains to their best use and created a camp that had won accolades in premier travel magazines around the world. The rich and the famous had stayed in her camp. It was her life’s work, her legacy and she couldn’t be more proud.

She let herself into the office and turned on the computer and the television. Portia, one of the waitresses from the dining room, knocked on the doorframe and entered with a tray of plunger coffee, low-fat milk, and two health rusks. Tertia bade her good morning and asked if she was well, and how her three year old was doing. When Portia left, Tertia sipped her coffee and reached for the remote. She was turning up the volume when she saw the crawler message on the bottom of the screen: Two dead, one missing in goldmine battle.

The phone rang.

‘Kak,’ she swore as she pressed mute. It was just after seven in the morning and the receptionist wouldn’t be at work until eight. She wanted to watch the television news – anything about mining was of interest to her these days. ‘Good morning, Lion Plains Lodge, Tertia speaking. How can I help?’

It was a New Zealander, a man with no concept of time differences, enquiring if they had a vacancy in three months’ time. ‘Just let me check, sir.’

Tertia minimised the window in which she had open a Global Resources media release – more spin and lies about their damned new mining project that would put her out of business – and clicked on the diary. She had a vacancy, and told the man on the phone, leaving out the fact that he might find his stay at Lion Plains, a ‘tranquil, exclusive private game reserve’, interrupted by the boom of explosives and the dust of an open-cut coalmine wafting over his luxury safari tent. He asked for a price and she gave him the standard rate. He said he’d get back to her.

Tertia hung up the phone and released the mute button on the television. The story on the mining incident was coming to an end. The reporter was doing a voice-over on some vision from an old story which included a shot of the entrance to the mine. It was Global Resources’ Eureka mine at Barberton.

The reporter said: ‘A company spokesman said the men were taking part in an environmental monitoring audit of a disused working. The men killed have been identified as Themba Tshabalala, aged twenty-two, a trainee environmental officer, and mine security guard Paulo Barrica, forty-one. The company said both men were valued employees who would be missed. The name of the third man, who is still reported as missing, has not been released.’

Tertia took a breath and held it. She reached for the phone again and dialled the cellphone number she knew by heart.

The phone went straight to voicemail. ‘Hi, this is Chris, leave a message.’

*

Outside, the sun was on the horizon. Chris has been missing for nine hours and there was still no word. Cameron hit the hands-free button on his phone and dialled the extension of his secretary, Hannelie. ‘Hann, please can you get me Themba Tshabalala’s home address?’

He heard her sniff. ‘Ja, boss. You want me to read it to you or email?’

‘Neither. I’m going out.’ He ended the call and got up from behind his desk. The Australians from Global Resources thought they could micromanage a mine in South Africa from the other side of the Indian Ocean, but he preferred not to work by memo or email.

Cameron left his office and walked into Hannelie’s smaller space, next door. She dabbed her eyes with a tissue and looked up at him. ‘I’ve written the address here. Themba and his wife were renting a small house in town. Paulo’s wife and children are in Angola, in Luanda. I’ve tried the cellphone but there’s no answer, just a voicemail message in Portuguese. I’ve got some more correspondence for you to sign.’

Cameron took the piece of paper from her. ‘I’ll get one of the Mozambicans to come see you and leave a message in Portuguese.’

Cameron had called his head of human resources, Nandi Radebe, from underground when Themba’s death had been confirmed. The gunfire from the ambush had been heard by some passing miners who’d called security. Nandi had notified Beauty Tshabalala of her husband’s death by telephone, but Cameron had told Nandi that he would visit the widow in person.

Hannelie retrieved some letters from the printer. She was a matronly woman of fifty, old-school and very formal, but when she came over to him her body shuddered and tears rolled down her cheeks.

Cameron took the papers and put an arm around her shoulders. ‘We’ll get through this, Hann. We must be strong for Chris.’

Hannelie dried her eyes. ‘I know we’ve lost men before, but to have them murdered in this way, and young Chris kidnapped. That poor Themba – he and his wife have a little one. I saw her at the gate on his first day.’

Cameron laid the letters on Hannelie’s desk and signed them. He checked the address of Themba’s widow and put the paper in his pocket. ‘I’m going to see her now.’

‘Roelf and Casper want to see you.’

On cue, his engineering manager and senior geologist appeared at Hannelie’s door. ‘I called head office again, but no news,’ Cameron said. ‘The Aussies say we can’t organise a rescue mission to go get Chris.’

‘Fokken wimps,’ Casper spat.

Roelf shook his head. ‘What are we going to do, boss?’