8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

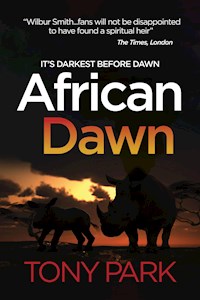

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Zimbabwe - a country in peril, a family torn apart, a battle to save a species.

In the broken country that is Zimbabwe, only the strongest can survive.

Three families – the Bryants, the Quilter-Phipps and the Ngwenyas – share a history as complex and bloody as the country itself.

Dedicated conservationists Paul and Philippa Bryant face an enormous struggle: to save their farm and small herd of endangered black rhinos from corrupt government minister Emmerson Ngwenya. Twin brothers, ex-soldier Braedan and environmentalist Tate Quilter-Phipps join the fight.

But the brothers’ own history is fraught, and when they fall in love with the same woman, Natalie Bryant, their rivalry threatens to not only derail the attempt to save the rhinos, but also puts the lives of all involved at risk.

With blood feuds still to settle, every one of these players will be drawn into the fray, and not one will remain unscathed.

African Dawn is the second chapter in Tony Park’s acclaimed Story of Zimbabwe series

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

About African Dawn

Zimbabwe - a country in peril, a family torn apart, a battle to save a species.

In the broken country that is Zimbabwe, only the strongest can survive.

Three families – the Bryants, the Quilter-Phipps and the Ngwenyas – share a history as complex and bloody as the cou.ntry itself.

Dedicated conservationists Paul and Philippa Bryant face an enormous struggle: to save their farm and small herd of endangered black rhinos from corrupt government minister Emmerson Ngwenya. Twin brothers, ex-soldier Braedan and environmentalist Tate Quilter-Phipps join the fight.

But the brothers’ own history is fraught, and when they fall in love with the same woman, Natalie Bryant, their rivalry threatens to not only derail the attempt to save the rhinos, but also puts the lives of all involved at risk.

With blood feuds still to settle, every one of these players will be drawn into the fray, and not one will remain unscathed.

African Dawn is the second chapter in Tony Park’s acclaimed Story of Zimbabwe series

For Nicola

Contents

Glossary

Baas – Afrikaans for ‘boss’. Common form of address for a white man, by a black man, in Rhodesia.

Batonka – Tribe indigenous to the Zambezi valley, displaced to higher ground when the Zambezi River was dammed and the newly formed Lake Kariba started filling in 1958.

British South Africa Police (BSAP) – Originally the police force of Cecil John Rhodes’s British South Africa Company, the BSAP retained its name as the police force of Southern Rhodesia (later Rhodesia) until the formation of Zimbabwe in 1980.

Bru – Slang for brother or mate (from Afrikaans).

Bulawayo – Second largest city in Zimbabwe, located in Matabeleland. The name Bulawayo comes from an Ndebele word meaning ‘place of slaughter’ or ‘place where he kills’.

Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) – The secret police and intelligence service of Rhodesia and, subsequently, Zimbabwe.

Chimurenga – Shona word for ‘struggle’. Zimbabwean history identifies at least two Chimurengas – the First Chimurenga of 1896–97 when the Shona and Ndebele took up arms against white settlers, and the Second Chimurenga of 1964–1980 (also known as the Bush War). Some veterans of the liberation struggle described the seizure of white-owned farms from 2000 onwards as the Third Chimurenga.

Chimurenga name – A nom de guerre adopted by pro-nationalist guerillas during the Second Chimurenga (Bush War).

China – Mate, from the Cockney rhyming slang ‘China plate’.

Gandanga – Shona word for a guerilla or freedom fighter, also used by white forces (plural: magandanga).

Gook – Derogatory term used by US soldiers for Vietnamese civilians or Vietcong fighters during the Vietnam War; subsequently applied to black Rhodesian guerillas by whites. It was probably brought to Africa by American Vietnam veterans who joined the Rhodesian security forces.

Government of National Unity (GNU) – Following disputed presidential elections in March 2008 and protracted negotiations, a GNU was formed on 13 February 2009. The GNU confirmed Robert Mugabe as President of Zimbabwe, and MDC-T leader, Morgan Tsvangirai as Prime Minister, with ministerial posts shared between ZANU–PF and the MDC factions.

Gukurahundi – Shona word meaning ‘the rain that washes away the chaff’; the term given to the brutal suppression of the Ndebele people following ZANU’s majority showing in the elections which created Zimbabwe. While ostensibly aimed at ZIPRA rebels, military operations by the Zimbabwe army’s North Korean-trained 5th Brigade reportedly resulted in the deaths of thousands of civilians.

Harare – Capital of Zimbabwe (formerly Salisbury, Rhodesia).

Joint Operations Command (JOC) – Co-ordinating body overseeing military and security operations in Rhodesia during the war, and subsequently in post-independence Zimbabwe.

K-Car – Killer car, a Rhodesian Air Force Alouette helicopter gunship, usually fitted with a 20 mm cannon.

Karanga – A grouping of the Shona tribe, from the Masvingo (formerly Fort Victoria) area. The Karanga made up the majority of recruits to the Rhodesian African Rifles, the predominantly black regular army battalions of the Rhodesian Army.

Matabele – White colonial pronunciation and spelling of the Ndebele tribe and language.

Matabeleland – The area covering west and south-west Zimbabwe, and the provinces of Matabeleland North and South; home of the Ndebele people.

MDC – Movement for Democratic Change – Main party in opposition to Robert Mugabe’s ZANU–PF. The MDC was formed in 1999 by former secretary general of the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions, Morgan Tsvangirai. The party subsequently split into two factions, the MDC-T (headed by Tsvangirai), and MDC-M, lead by Arthur Mutambara.

Mtengesi – Shona word for ‘sell-out’ – someone who sided with the white government during the Bush War or, later, with the MDC or other opposition to ZANU–PF.

Mugabe, Robert Gabriel (1924–) – Prime Minister, then President of Zimbabwe since 1980.

Muzorewa, Bishop Abel (1925–2010) – Leader of the United African National Council (UANC), and Prime Minister of the short-lived Zimbabwe–Rhodesia, a multiracial government formed in 1979 as part of a doomed internal settlement proposed by Ian Smith.

Ndebele (see Matabele) – Second largest tribe in Zimbabwe, descended from the Zulus of South Africa.

Nkomo, Joshua (1917–1999) – Founder and leader of the National Democratic Party, which subsequently became the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU). Nkomo was Vice President of Zimbabwe from 1987–1999 after ZAPU merged with ZANU to form ZANU–PF.

Oke/ouen – Slang for man (from Afrikaans).

Operation Noah – Rescue of wildlife stranded by the damming of the Zambezi River in 1958–1964 to form Lake Kariba. More than six thousand animals were saved by game department officers and volunteers.

Pioneer column – Force raised by Cecil John Rhodes and his British South Africa Company in 1890 to annex parts of modern Zimbabwe before the Germans or Portuguese could lay claim to the territory.

Porks – Derogatory rhyming slang term for Portuguese, from ‘pork and cheese’.

Rhodesia – British colony founded by and named after Cecil John Rhodes. The name was officially adopted in 1895 and subsequently changed to Southern Rhodesia. The country renamed itself the Republic of Rhodesia after unilaterally declaring independence from Britain in 1965, following Britain’s refusal to grant independence without majority rule. The name was changed, briefly, in 1979 to Zimbabwe–Rhodesia under a multiracial government, then to Zimbabwe in 1980.

Rhodesian African Rifles (RAR) – Regular army unit of the Rhodesian Security Forces consisting of black African soldiers and noncommissioned officers, and white officers.

Rhodesian Front (RF) – Formed in 1962, and headed by Ian Smith from 1964–1979, the RF was the governing political party in white-ruled Rhodesia until the forming of the ill-fated transitional government of Zimbabwe–Rhodesia.

Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI) – All-white regular army unit of the Rhodesian Security Forces.

Salisbury – Capital of Rhodesia (now Harare, Zimbabwe).

Selous Scouts (Skuz’apo) – An elite multiracial unit of the Rhodesian Security Forces, named after the big-game hunter Frederick Courteney Selous. Black African Selous Scouts dressed in enemy uniforms and operated in tribal areas, tracking and ambushing guerillas. The scouts boasted the highest kill ratio of any Rhodesian unit.

Shona – The majority tribe of Rhodesia/Zimbabwe.

Sithole, Reverend Ndabaningi (1920–2000) – Founder of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) in 1963, later overthrown by Robert Mugabe.

Smith, Ian (1919–2007) – Prime Minister of Rhodesia and leader of the Rhodesian Front Party from 1964 to 1979. Smith orchestrated Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain in 1965.

Southern Rhodesia African National Congress – A pro-independence and black majority rule political organisation which lasted from 1957 until it was banned by the white Rhodesian government in late 1958.

Terr – Terrorist; term used by whites for black guerillas/freedom fighters.

ZANLA – Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army – The military wing of ZANU. Predominantly Shona, ZANLA’s members were trained and advised by communist China and operated during the Bush War from bases in Mozambique.

ZANU– Zimbabwe African National Union – Predominantly Shona nationalist political party, founded in 1963.

ZANU–PF – Zimbabwe African National Union–Popular Front – Formed in 1987 with the merger of ZANU and ZAPU, ZANU–PF, headed by Robert Mugabe, was the dominant political party in Zimbabwe until the emergence of Morgan Tsvangirai’s opposition Movement for Democratic Change.

ZAPU – Zimbabwe African People’s Union – Predominantly Ndebele nationalist political party.

ZESA – Zimbabwe Electricity Supply Authority – Also commonly used slang term for electricity in Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe, Republic of – Formerly Southern Rhodesia, the Republic of Rhodesia, and Zimbabwe–Rhodesia, the Republic of Zimbabwe, formed in 1980, takes its name from the Shona-speaking Kingdom of Zimbabwe, which flourished from 1250 to 1450 from its stone-built capital of Great Zimbabwe, near Masvingo (Fort Victoria).

ZIPRA – Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army – The military wing of ZAPU. Predominantly Ndebele, ZIPRA’s members were trained by Russia and operated from bases in Zambia.

ZUPCO – Zimbabwe United Passenger Company – Bus operator in Zimbabwe.

PART ONE

Rhodesia

1

Southern Rhodesia, 1959

Makuti learned to swim almost as soon as he learned to walk. He didn’t know that he wasn’t born to enter the water; he just followed his mother in and did what she did.

The rain had been falling all his short life. Makuti couldn’t know it – how could he – but it was not supposed to be like this. It was not meant to pour down so heavily from the skies, at this time of the year. It was not natural.

His first steps were in the mud and he tried as best he could, on his short legs, to keep pace with his mother who was terribly stressed. She walked in circles and Makuti’s path was made harder because he had to lift his little feet in and out of the ever-deepening footprints his mother was pounding into the sticky slime.

When she stopped abruptly, Makuti skidded and bumped into her legs. He fell over and, instead of scrambling to his feet, enjoyed the peace of lying there for a moment, wallowing in the cloying mud. When he tried to stand, he slipped and rolled some more, and found that he enjoyed it.

His mother turned and looked down at him. She snorted and stamped her foot. He dragged himself upright again – the brief moment of play over.

Makuti was hungry. Although he was already walking, it would be some time before he was weaned – such was their way – so he sought out the solace and nourishment of his mother’s teat. She brushed him aside and, hurt, he stumbled and sloshed after her. The rain started again and spattered his back. He was tired, hungry and cold.

His mother shook her head. She was starving too. The ring of their forlorn footsteps grew shorter each day, as the rain continued to fall and the river continued to rise. In the days before she had given birth, Makuti’s mother had exhausted herself climbing higher and higher up a hill, which had now become an island. Although they were safe from the rising waters up here on this rocky outcrop, there was nothing to eat and the new mother was half-crazed with hunger.

Thunder rolled down the valley and lightning ignited the night sky. Makuti’s mother walked to the floodwaters’ edge and waded in. And Makuti, not knowing any better, plunged in joyfully behind her and started to swim.

*

‘Bejane!’

Paul Bryant raised a hand to shield his eyes from the glare of the morning sunshine on the still waters. The lake was the same molten silver as the hazy sky and it was virtually impossible to discern the horizon. Paul pulled the battered pair of binoculars from their worn leather case to see what fourteen-year-old Winston Ngwenya was pointing at.

‘Well spotted, Winston. It’s a rhino all right.’

‘There are two.’

Paul moved the focusing wheel and saw the youngster was correct again. Bobbing behind the first horned head was a little dark blob. ‘A calf.’

‘Ah, but the mother will be trouble, baas.’

‘Dad, let me see.’

‘Steady, George!’ Paul lurched as his son inadvertently shifted the outboard engine’s tiller in his haste to catch sight of the swimming black rhinoceroses, but regained his balance. He smiled to show George he hadn’t meant to chastise him, just to warn him.

George set the throttle to neutral and the wooden dinghy slowed. Long-limbed and angular, with his father’s height and his mother’s blonde hair, George had the awkwardness of adolescence and the promise of manhood competing for control of his every move and word. Paul smiled as he handed his son the binoculars.

Winston, kneeling at the bow, reached out a hand to steady his friend, but George brushed it away. ‘I’m fine.’

It was amazing what a difference a year could make, Paul thought. Winston’s body was filling out quickly and he was almost a man. His voice was breaking and his movements around the boat were self-assured and confident. Bryant thought of the African boy as a second son, almost. He was the firstborn child of his good friend Kenneth, who taught in the black township of Mzilikazi, on the outskirts of Bulawayo, back home in Matabeleland.

Kenneth and his wife, Patricia, had two more children after Winston, a girl and a boy, Thandi and Emmerson. All three of their children were healthy and strong, which was something to give thanks for.

‘I see them, Dad,’ George said. ‘Too bad Mom can’t be here.’

Paul nodded. He, too, wished she were here with him, instead of back on the farm, way out near the Bechuanaland border.

‘Go, Paul. For God’s sake, please go – you’re driving me bloody mad,’ she’d urged him. They’d tried for a second child after George had been born, back in 1946 after Paul had come back from the war, but Pip had miscarried. Then, thirteen years later, at the age of thirty-nine, she had told him the news that she was expecting what the Afrikaner farmers living in Rhodesia called a laat lammetjie.

This, however, was no late lamb. It was a tiny human life that Philippa was carrying. Paul had been adamant that Pip should stop work around the dairy and spend more time indoors resting. They’d had fights over it, but she’d stood up to him, telling him that she would not live her life in fear – not even of another miscarriage. He’d seen in her the same fierce independence and stubbornness she’d shown as a volunteer policewoman during the war, when they’d first met.

When the call had gone out from the Rhodesian Game Department in the early days of Pip’s pregnancy for volunteers to help with a massive operation aimed at saving wildlife stranded by the rising waters of the newly created Lake Kariba, they had gone as a family to camp near the growing but still primitive township that had sprung up near the dam construction site.

The three of them had known bugger all about how to save wild animals from drowning when they’d arrived five months earlier, but since then they had learned how to corral and drive impala, kudu and waterbuck into the lake, then shepherd them towards the mainland. They had plucked deadly mambas and irate cobras from waterlogged trees and rescued a host of smaller creatures then transported them by boat to the new banks of the swelling Zambezi River.

One thing Paul had learned from his time working as a volunteer on Operation Noah, as the rescue operation had been dubbed, was that every animal could swim. The problem was that some could not swim as far as others. The rescuers’ hearts had soon hardened to the sight of the bloated bodies of dead buck that hadn’t made it, or half-eaten remains of animals that had literally fought each other to death.

Earlier in her pregnancy, Pip had come out most days on the boat for an hour or two at least, and proved herself as able and fearless as any of them. Paul was sick with worry about the baby sometimes, but Pip was happy to pull on his old wartime pilot’s goggles and a pair of motorcycle gauntlets and pull a mamba from a tree, or sit in the boat cradling a soaking, shivering baby baboon whose mother had drowned.

Paul had lived in Southern Rhodesia since the end of the war. He’d had few family or prospects to encourage him to return to his native Australia and he’d fallen in love with Pip in 1943, when he’d been based at Khumalo airfield, near Bulawayo, as the adjutant of an aircrew training base. When he’d returned to Africa after being demobbed in 1945, he’d realised he’d also fallen for the continent.

There was a wildness of spirit in Africa that had once existed in Australia but was fast disappearing. Out here, in the wilds of Rhodesia, things were very different. Life was harder in Africa, and it had to be lived on the edge. As such, people seemed to enjoy things more, and live for the day.

Paul had taken Pip back to Bulawayo and the family dairy farm after their first month with Operation Noah, at the same time that George was due to return to school. But as the next school holidays approached, George pleaded with his parents to be allowed to return to Kariba to help out again with the relocation of animals. Paul did not want to go without Pip, but she all but ordered him to take their son back to the growing lake. Paul had been reluctant to leave her alone and heavily pregnant, but if he’d learned one thing in the past sixteen years it was that his diminutive Rhodesian wife was not to be disagreed with. He’d left with George and Winston, promising to be back in plenty of time for the birth, which was still not due for another month.

‘Look, Mr Bryant, she is going the wrong way,’ Winston said.

Paul saw he was right. ‘Head for that island, to the left, George. We’ve got to try and drive her towards the mainland.’

George nodded, his face set with concentration. The quickest way to the rhino would be to come close around a trio of dying trees that marked what had once been the top of a hill. As they closed on the trees Paul joined Winston at the front of the boat, and both peered ahead looking for submerged trunks that might ground them or tear the bottom out of the boat, which had been designed for waterskiing and fishing rather than rescuing animals.

‘Stick!’ Winston called, pointing off to starboard. George swung the tiller and the boat glided past the dangerous obstacle.

Paul scanned the nearest tree. ‘There’s a cobra up there. Make for it, George.’

As George turned again and cut the throttle, allowing the boat to coast up to the top branches of the drowning tree, all three of them looked down at the bottom of the boat to protect their eyes from the potentially blinding venom. Paul took off his Australian Army slouch hat, a souvenir of his war days, and put on his old flying goggles. He reached for a steel pole whose end had been fashioned into a u-shaped hook. Winston cried out and wiped his bare shoulder as a jet of venom lashed his skin.

‘Come left,’ Paul said. He placed a hand on Winston’s neck to stop the boy from looking up, and ducked sideways as the cobra reared in the branch and spat another jet of milky venom towards him. Droplets spattered the goggles’ right lens and burned his cheek. Paul reached for the snake. It pulled back and then struck, lightning fast, at the pole, but Paul was able to trap its head against the waterlogged trunk of the tree. ‘Pass me the bag, Winston.’

His head still bowed, Winston raised the hessian bag to Paul then took hold of a nearby branch to secure the boat, while Paul grabbed the pinned snake behind the back of its head and thrust the writhing, hissing reptile into the sack.

‘Can we go for the rhino now, Dad?’

Winston looked up and laughed at George’s deadpan remark.

‘Head for the rhinos, George, fast as you can,’ Paul said.

*

Philippa Bryant exhaled and leaned against the hot metal of the Chevrolet bakkie as the young African man loaded her paper bags full of groceries into the rear of the vehicle.

‘Thank you, Sixpence,’ she said, and handed him a few coins.

‘Are you all right, madam?’ he asked.

‘Fine, thank you.’ She forced a smile and he walked back into Haddon and Sly. She was actually far from fine. She felt hot, fat, tired and thoroughly sick of being pregnant. She and Paul had been ecstatic about having another baby – at the start – but now she found herself moodily alternating between being annoyed and terrified. It had been many years since her last miscarriage, yet being pregnant again had reopened her old wounds and poured salt into them. At the same time she was full of nervous hope for the baby that kicked inside her.

She regretted ordering Paul to take George to Kariba for the school holidays. She wanted to be there with them, or, if she couldn’t have that, she wanted them both back at the farm. Now.

Pip opened the door of the car. ‘Bloody hell.’ She realised she’d forgotten the bread. She was terribly forgetful these days, and remembered it as a symptom of her first pregnancy. ‘I’m too old to be pregnant,’ she said out loud as she walked slowly back into the department store. She felt like crying when she found the bakery had just sold its last loaf. Dejected, she turned and headed back out into the street. There was a bakery a block down Fife Street.

The sight of purple jacaranda blossoms cheered her a little. She knew from her time as a volunteer policewoman that this city of Bulawayo sometimes lived up to its Ndebele name, as a place of slaughter. She’d been involved in a couple of murder investigations and several cases of rapes, stabbings and beatings. She herself had been a victim of domestic violence at the hands of her first husband, before she’d met Paul. Fortunately, Charlie had died during the war. Fortunately for him, that is, because she’d decided after a couple of years as a volunteer constable that she would have had him arrested on his return from duty overseas, war hero or not. She knew that the orderly grid of wide, clean-swept streets and the impressive, stately public buildings of Bulawayo were, in some cases, just a façade of order. Pip had seen the grubbier side of the city – the blood, vomit and sewage in the streets of the black townships, and the seamy private lives of the outwardly upstanding members of the white community.

Pip only came to town once every month or so, to shop for what she couldn’t grow or make herself. It was a chore at the best of times, but on her own and carrying another person in her belly it really was no fun at all.

‘Howzit, Pip?’

She looked up and saw Fred Phipps touching the brim of his hat. Fred farmed in the same district as she and Paul, and they ran into each other at parties once or twice a year. The Bryants and the Quilter-Phippses weren’t close friends, but they got on fine. Fred had played in the same rugby team as her first husband, Charlie, and Pip often sensed that he disapproved of her marrying Paul. Word had gotten around town during the war that she and Paul had become an item virtually as soon as she had heard of Charlie’s death. Pip didn’t care, and she had told anyone who bothered to listen that Charlie had been a bastard, despite receiving a posthumous Military Medal for his actions in the desert in North Africa.

‘Fine, Fred, and you?’

‘Fine, fine. You must be due soon, hey?’

Pip nodded, and her head felt heavy. She was sick of being asked the same question. ‘A month.’

‘Sharon’s due any day. I’m just busy in town getting some things for when I have to fend for myself on the farm.’

Pip smiled and felt a genuine warmth for the man. She’d heard, ages ago, but had since forgotten, that his wife was pregnant. ‘Please give her my best, Fred.’

‘I will.’ He paused and cocked his head. ‘What’s that noise?’

Pip heard shouts, and more rhythmic noise, like singing, coming from around the corner. She started walking in the direction of the sound, and Fred, who had been walking in the other direction, turned to follow her. Pip reached the closest corner and saw a group of about forty African men and women holding placards. One read, Down with unfair bus fares.

‘Bloody munts,’ Fred said.

Pip turned and looked at him. ‘What’s all this about?’

‘Probably tied up with the bus fare protests in Salisbury. A friend of mine in the police told me they’ve had to crack a few kaffir skulls up there because the munts are complaining about some increases in the UTC bus fares. I mean, why should we whites be subsidising their bloody travel? If a bus company needs to charge more to make ends meet, then who are they to object?’

Pip frowned. Very few African people owned a bicycle, let alone a motor car and for most of them the bus was the only affordable way to travel. Now that Fred mentioned the Salisbury trouble she did remember reading somewhere that the fare hike meant some Africans were paying up to twenty per cent of their meagre wages on bus tickets.

‘Come on, Pip,’ Fred said, putting a hand on her arm. ‘We’d best get you away from this mob.’

She shrugged off his touch, then turned and gave him a smile to show him she meant him no offence. All the same, Paul was the only man she wanted touching her. And she could look after herself. ‘I’m fine, Fred. I’m only going to the bakery.’

Fred looked past her, at the crowd. The group was well dressed – the men in suits and the women in neatly pressed skirts and blouses. A few were singing, and two of the men were walking up and down the street handing out pamphlets of some sort. Most of the pedestrian traffic was white people and they uniformly ignored the Africans and their handouts. A white man stopped to berate the group and tell them to go back to the bloody trees they’d climbed out of.

One of the men handing out flyers had his back to Pip, but he looked very familiar. When he turned around she saw it was Kenneth Ngwenya. Pip ignored Fred’s panicked warning cry from behind her, looked both ways, and walked across the street towards the protesters.

‘Kenneth!’

The tall Ndebele schoolteacher turned and smiled. He closed the gap between them. ‘Hello, Pip, how are you?’

‘I’m fine, and you?’ He nodded and told her he was well. ‘Is this what you do in your school holidays, organise civil disobedience?’

He chuckled. ‘It’s a peaceful demonstration. The bus companies are holding people to ransom. There have been big demonstrations in Salisbury and I, as an interested community member, wanted to show my support for the people opposed to these increases. We’re calling on all African people to boycott the bus services until the companies drop their prices again.’

Pip knew that Kenneth was much more than an interested community member. He was a member of the Southern Rhodesia African National Congress, the dissident pro-black-independence organisation headed by Joshua Nkomo. As a native-born Rhodesian, and the descendant of one of the members of Cecil John Rhodes’s Pioneer Column, part of Pip bridled at anyone – African or white – wanting to destabilise the Rhodesian political scene. Rhodesian Africans, in her opinion, were better educated and better treated than any other blacks on the continent. There was agitation for majority rule in countries to their north and Pip, like most other whites, feared what might happen if Britain were to make a blanket decision to give independence too soon to people who were not prepared or educated enough to rule a country themselves. She liked Kenneth, although she found his wife, Patricia, surly to the point of being objectionable. Pip got the feeling that the woman disliked all white people. Kenneth, however, was like Paul – he took people as he found them. Paul often had Kenneth over to the farm for tea or went fishing with him after church on Sundays.

Pip wanted to ask Kenneth more about the demonstration, but their conversation was interrupted by the clanging of a police car’s bell. They looked down the street and saw two patrol cars speeding towards them. The cars skidded to a halt and four officers got out of each vehicle, drawing truncheons as they strode towards the protesters.

‘Break it up. This is an illegal gathering and you are hereby ordered to disperse,’ called Chief Inspector Harold Hayes from the head of the group. Pip cringed. She hadn’t seen the bull-necked policeman for years. Hayes had been a sergeant during the war and Pip had been partnered with him for a while. He was an inept, racist bully, and proof that many people in uniform were promoted far above their capabilities simply because they hung around long enough. ‘You, move away from that woman!’

Hayes was pointing his truncheon towards Kenneth, but Pip could see the overweight police officer hadn’t recognised her yet. ‘Chief Inspector …’

As Pip started to walk around Kenneth, he put out his arm, as if to tell her not to involve herself. At the same moment two of Hayes’s young British South Africa Police constables bolted ahead of their commander, obviously ready to break up the gathering by force if they were given the slightest encouragement.

The protesters had stopped their singing and chanting and looked at each other for guidance. Some stood defiantly facing the oncoming police, but two younger men and a woman started to flee. One of the men, perhaps a student, was looking back over his shoulder at the advancing constable as he ran, and as Pip moved out of Kenneth’s protective reach, the man collided with her and she fell over backwards, hitting the ground hard.

‘No!’ Kenneth yelled.

‘He’s kicking her, sir!’ one of the junior constables cried out as the young man’s legs became entangled in Pip’s and he dropped to one knee beside her. The policemen raised their batons and charged.

2

‘Come around behind her, George,’ Paul Bryant said to his son. George swung the tiller and the boat scribed a wide arc on the silvery surface of the lake. At least it was calm today, Paul thought.

Lake Kariba was still filling, but it was already a monstrous body of water. By the time it reached its capacity, in three to four years, it would be two hundred and twenty kilometres long and up to forty kilometres wide. The huge expanse was already proving treacherous. As well as boats running aground, or having their hulls gashed open by submerged treetops, the freshwater lake was prone to violent storms that whipped up waves of up to a metre. More than a few small boats had capsized and sunk, their crews suffering the same fate as the baboons and monkeys the volunteers were continually finding stranded in branches.

The black rhino and her calf were still swimming steadily towards certain death. Paul reckoned they were paddling towards another stand of trees that were half-submerged. From water level the branches might have looked like an island, but the animals were paddling further out into the lake instead of to the shore, which was also close but out of the rhino’s poor field of vision.

‘Check, Dad,’ George called, and pointed to a fish eagle executing a shallow dive off to their left. The majestic snowy-headed bird had its talons extended ahead and as it brushed the surface of the water it plucked out a sizeable bream. It beat its long red-brown wings and made for the nearest tree, where it landed and began ripping the fish apart.

The damming of the Zambezi had been a death sentence for thousands of animals, but the rising waters had also provided an unending feast for other creatures. Fish eagles were breeding like crazy and their high-pitched lilting calls were becoming synonymous with any trip to the lake. The lake was being seeded with fish species to provide food for the nation, and a livelihood for the Batonka people who, like the animals that once lived in the valley, had been moved to higher ground.

Some tribespeople had resisted the government’s repeated urging to relocate to new resettlement villages, and there had been protests and violence. At Gwembe, on the Northern Rhodesian side of the lake, troops and police had been called in to forcibly relocate some Batonka, but the villagers had rebelled and, armed with spears and clubs, had charged the security forces. Several Batonka had been killed by gunfire.

Paul shielded his eyes against the glare and tracked the rhinos’ progress. This was Africa, he told himself. Life and death, predator and prey. Someone always lost while someone – or something – grew fat. If they did somehow manage to steer the rhino cow to the mainland, her tiny calf might still be taken by a crocodile. Like the fish eagle, these prehistoric predators were thriving on the diet served up by the man-made sea. Every crew of volunteers had tales to tell of near misses by the cunning, ruthless ngwenya, whose numbers were rising in proportion with the increasing flood level and ever-growing number of animal carcasses.

Paul looked back at George. The motion of the boat through the hot, still curtain of African air produced enough breeze to ruffle the boy’s bushy blond hair. His tanned skin highlighted his mother’s blue eyes even more. George would grow into a handsome young man, and Paul almost envied his son being able to come of age in such a fascinating, bounteous and prosperous young country. Paul had lived through the depression in Australia and gone off to war as a young man. The things he’d seen and the friends he had lost during his time in Bomber Command had nearly destroyed him, but meeting Pip had turned his life around. He’d finished the war a better man, back on active service flying twin-engine Mosquito aircraft in a pathfinder unit, and he’d left the Royal Australian Air Force as a highly decorated wing commander. The medals meant nothing to him, though, and his strongest hope was that George and the new baby could live in peace for the rest of their lives.

George grinned back at him.

‘Will the electricity from the dam reach Bulawayo, Mr Bryant?’ Winston asked.

Paul nodded. Winston had an enquiring mind and was proving to be a good student at the Catholic college he attended in Natal, South Africa. There were few opportunities for higher education for young Africans in Rhodesia, yet in the more liberal provinces of South Africa, at the far extent of the National Party Government’s reach, privately funded church schools offered local students and those from other African countries a chance to better themselves, at a price. Paul had tried to give Kenneth money towards Winston’s education, but his friend had refused the charity. Instead, Kenneth had agreed that Winston would work at the Bryants’ dairy during every school vacation. The other employees on the farm didn’t know, but Winston was being paid well over the odds, on the assumption that most of his earnings went towards his school fees. The arrangement allowed Kenneth to retain his dignity and Winston to continue his schooling. Sometimes, especially on the farm, Winston called Paul ‘baas’ in order to not flaunt his education or close connection to the boss and his family, but Paul preferred plain old ‘mister’.

‘The power from the hydro-electricity plant will go into the national grid, so it could end up anywhere, theoretically.’

Winston nodded. ‘Then despite the fact that the Batonka and the animals are suffering, this dam is a good thing.’

Paul shrugged. He knew the job of politicians was to make tough decisions – when they had the balls to do so – but all three of them had seen the sad toll of animals killed by the flooding. Paul guessed, too, that Winston’s father had some strong views on the forced relocation of the Batonka, which had probably filtered down to his son.

‘There are winners and losers,’ George interrupted from behind them. ‘Some animals, like some people, were smart enough to move to higher ground. The lions mostly moved inland when the waters rose – didn’t they, Dad?’

George was right about the lions – on the evidence they’d seen so far – but Paul was uncomfortable with the inference that the Batonka who had resisted relocation were stupid or ‘losers’ because they were opposed to leaving their ancestral homelands. Personally, having made a home in Rhodesia, Paul couldn’t imagine a worse fate than being kicked off the farm by the government and told he would have to live somewhere else. He was about to make the point when Winston pointed out that the rhinos had changed course and were now heading towards them.

‘Easy,’ Paul cautioned George. ‘Come alongside the mother, my boy. She’s still heading the wrong way. Let’s try and shepherd her.’

George slowed the throttle and it looked as though they would be able to take up a position behind the calf, moving at more or less the same pace as the ponderous swimmers.

‘See how the calf is behind its mother,’ Paul said to the boys. They were all momentarily entranced by this rare opportunity to come close to an animal that had a justified reputation for unpredictability and fierceness in the wild. ‘That’s one of their downfalls. White rhino cows make their young walk ahead of them, so they can keep an eye on them, but black rhino babies follow their mothers, which make them more vulnerable to lions and hyenas when they’re small.’

‘Like the difference between black mothers and white mothers. A black mother carries her picannin on her back, and a white woman pushes hers in front with a pram,’ Winston said.

Paul and George laughed. ‘But, Dad,’ George asked, ‘isn’t it bad for the mother rhino to go ahead of her baby? What if it gets lost?’

‘There’s a reason for everything in life, George,’ Paul said. ‘Black rhino live in thick bush and often the mother needs to walk ahead to clear a path for her calf. White rhino live on the grasslands where visibility is better.’

The lesson ended when the rhino stopped.

It took Paul’s brain a full two seconds to comprehend what had happened. The rhino’s feet must have touched ground on an unseen hilltop beneath the water’s surface. It had probably been a rocky kopje, with no trees to give away its position. The water was up to the rhino’s chest as she turned and issued a long, loud snort that rippled the lake’s shiny surface in front of her. The calf, confused, continued to paddle up beside its mother. Its legs were too short to touch the bottom, and its swimming became instinctively more panicked. Its little head thrashed from side to side as it picked up the shape, size and noise of the approaching boat.

‘Cut the throttle! Reverse, George, reverse!’

But they all acted a fraction too slowly. The mother rhino charged.

Each step was boosted by the effect of the water, allowing the cow to surge forward on a near weightless body. When her curved horn splintered the wooden boat just above the waterline, the impact sent Winston toppling over the far side into the water.

Paul crashed to the bottom of the boat and had to roll to one side to escape the wicked point of the rhino’s horn. The beast shook her head and grunted and snorted bubbles in the water as she fought to free herself.

As the rhino lowered her head the boat tipped to one side and Paul slid closer to the horn’s point. He could hear her grunting and the sound terrified him almost as much as the deadly tip. Water seeped in through the hole she’d created, then poured over the gunwale as she pushed down again, threatening to capsize the small boat.

George revved the engine hard and the outboard screamed. ‘It’s still in neutral,’ Paul called. As Paul got to his knees and started moving aft he saw Winston’s arms thrashing in the water. The boy’s mouth was open wide in a scream that was drowned out as his head slid below the surface.

Paul crawled to George and reached out, turning the throttle setting to reverse. The boat strained against the rhino, locked in a tug of war. As the great beast finally unhooked her horn the boat surged backwards and Paul used the momentum to help propel himself over the side and into the cool waters of the lake.

When he broke the surface he waved at George to keep going in reverse. Paul struck out, overarm, for a pale pink palm he saw disappearing below the lake’s surface. He duck-dived and groped blindly in the murky waters for Winston. He flailed around him but couldn’t feel the young African.

He swam to the surface again and sucked in a lungful of air. George was turning around and had the boat back in forward gear. Paul shook his head, but he didn’t have time to warn his son. The rhino was walking in circles on her underwater island, and she shook her head and snorted again when she saw him. Paul wiped the water from his face and eyes. ‘Winston!’ To lose his friend’s son would be like losing his own.

Paul thrashed around in circles until he saw the bubbles. In two fast, hard strokes he was there and diving down again. His outstretched hand brushed something that flicked and groped for him. Paul wrapped his hand around Winston’s forearm and felt the boy weakly grasp his in return. He kicked for the surface but Winston seemed stuck. He sensed the boy’s panic as he let go of his arm and prised Winston’s fingers from his own arm. Paul dived deeper and felt for the problem. Winston’s leg was trapped in the fork of a submerged tree. Paul grabbed his foot and untangled the creeper vines that had wrapped around his ankle. He took hold of the young man’s limp upper arm and kicked again for the sunshine above.

When he broke free of the water’s grasp, Winston was floating motionless beside him.

‘Over here,’ he spluttered unnecessarily, because George was beside him in the boat in an instant, and reaching over the side to help him. Paul had underestimated George’s strength as he felt his son drag Winston almost effortlessly over the gunwale. Paul grabbed the boat and boosted himself aboard. He rolled the unconscious Winston onto his side and checked his airway was clear, then pushed him onto his back and blew into his mouth. Paul broke from the kiss of life and started pumping the boy’s chest.

‘Come on.’ He lowered his lips again to Winston’s and blew in another deep breath. The boy coughed water and began spluttering. Paul rolled him onto his side again and thumped him on the back as Winston continued to cough.

‘The rhino, Dad!’

Paul saw, too late, that they had been drifting closer to the cow and her calf while reviving Winston. She lifted her head and blew a challenge at them, then lowered her horn and started her waterborne charge again.

Their rocking movements up and down the boat had caused water to leak in through the hole the rhino had gored in the planking. Paul reached in the bilge for the wartime .303 he brought along for emergencies. This qualified as one, he reckoned, though he had no idea if the round would kill the cow or even slow her. He worked the bolt and as he raised the rifle to his shoulder he saw, in his peripheral vision, George’s arm moving in a blur.

The smoking tin canister tumbled through the air, hissing towards the rhino. Suddenly it detonated with a bang as loud as a hand grenade and in a storm of instant lightning that rocked all of their senses to the core. The thunder flash had the same effect on the rhino, which stopped mid-charge and turned away from the painful burst of noise and light. She started swimming and her startled calf paddled slowly behind her.

‘Good work, George,’ Paul said, clasping his son’s shoulder. They’d had three thunder flashes – ex-army hand grenade simulators – in the boat since their last round-up of impala and kudu on an island further south in the lake. The noisy devices were used to scare the antelope into running into a funnel of nets that forced them into the water, where they were made to swim towards shore, or into a boma where they could be roped and carried to waiting boats. George had saved the day, and the rhino cow, by his quick thinking. Winston was on his knees, still retching, but apparently not permanently harmed by his own near-death experience.

‘Boat,’ George said, hiding his red-cheeked flush of pride by pointing towards the oncoming craft that cleaved through the lake’s molten metal surface. ‘It’s Rupert Fothergill, by the look of it.’

Paul cupped his hands either side of his mouth, and yelled, ‘Rhino!’ His first priority now was to get the two boys back to shore, so they could give Winston time to rest and recover. He pointed to the cow and her calf, hoping Fothergill would take over the shepherding duties, but the ranger’s boat ploughed on towards them, its bow riding high until the driver cut the engine and allowed them to coast up to the wallowing dinghy.

Before Paul could explain what they’d been up to, Fothergill held up a hand. ‘Paul, I’ve just received a radio message … a friend of yours in Bulawayo, a Doctor Hammond, got through to the ops centre at Kariba by telephone. It’s your wife, Paul … she’s been taken to hospital. It’s not good.’

*

George and Winston sat side by side on a green grassy spit of land in the newly declared Kuburi wilderness area, on the edge of the growing inland sea.

‘I wonder what happened to that rhino and her calf.’

Winston lifted the galvanised-tin water bucket and pushed the end of the mopane log deeper into the fire, balancing the bucket again on the newly stoked coals. ‘Another man from the camp told me she ran through the township at Mahombekombe, not far from the dam wall, and then up into the hills.’

‘Shame,’ George said, but his grin at the thought of the rhinos stampeding through the workers’ shanties faded when he thought of the animals’ plight. ‘But her little baby didn’t look like he would make it. He was struggling to keep up with her when we left to …’

George looked out over the lake and stared at the red ball heading for the water. The sun sank like his spirits. He hated to think of his mother in hospital, in pain, and wondered what had happened to the baby brother or sister she was carrying. He felt his throat constrict and his eyes began to sting. He would not cry, he told himself. He was nearly a man. He felt Winston’s hand on his shoulder and looked at him.

‘Your mother is a good woman. God will look after her, George. My mother … she is angry at everything all the time. She is angry at me, my father, the white people …’

George smiled. Patricia Ngwenya’s temper was legendary in the district and his mother, who rarely had a bad word to say about anyone, had a favourite word for Winston’s mother – insufferable. It was good to have her son here with him, though. George sometimes felt he had missed out, not having a brother of his own, but he and Winston were close enough to be family.

Rupert Fothergill had told George’s father, when they’d met out on the lake, that there was a light aircraft leaving Kariba airstrip within the hour for Salisbury, but there was only space on board for one person. ‘Go, Dad,’ George had said, seeing the indecision further furrow his father’s already stricken face.

‘We’ll take care of the boys until you can send word or organise transport for them,’ Fothergill had added.

George didn’t feel nearly as brave now as he’d tried to be on the boat. He wanted to be by his mother’s side, but at the same time he was scared of finding out what might be wrong with her. He couldn’t bear the thought of anything happening to her; it was easier, he decided, for him to stay here on Operation Noah and act like everything was OK.

‘You and your father saved my life today,’ Winston said.

George looked at his friend and realised he wasn’t the only one who’d been doing some serious thinking. ‘You would have done the same for us.’

‘Of course,’ Winston nodded.

George picked up a stone and tossed it as far out into the water as he could. It landed with a satisfyingly loud kerplunk.

‘What do you want to do when you leave school?’ George asked.

‘Me, I am going to join the army.’

George looked at him in surprise. ‘I thought you’d become a teacher, like your dad.’

Winston shook his head. ‘I’m sure that’s what he has planned, but I don’t like school enough to want to stay in the classroom for the rest of my life.’

George laughed. ‘I know what you mean.’ He looked up at Venus, rising bright in the purple twilight, and cocked his ear and held up a finger and pointed towards the far-off call of a lion. When it was still again, he asked, ‘Why the army?’

‘I want to be a warrior. Your father was in the war; he was a great warrior.’

‘He was a pilot.’

‘Yes, but he still fought for his country. I wouldn’t want to fly an aeroplane, but I would like to be paid to fight. My mother says my father talks too much, and that he should learn to stand up and fight for what he believes in.’

‘I asked my dad once about joining the air force,’ said George, ‘and he told me he would do everything in his power to stop me. He says the war was terrible and that no one should ever have to go through what his generation did.’

‘Still, I don’t want to be a teacher. Myself, I want to spend my days among warriors, not children. I want to drink beer and have many women. What about you?’

There were hippos honking in a newly created bay, behind and off to their left, but they went quiet when the lion started calling again, closer this time. ‘I’d like to be a game ranger. I like it out here in the bush.’ He’d also like to be with Susannah Geary, whom he’d seen in church in Bulawayo whenever he was home from school.

‘I don’t like the bush. But it’s good to get away from school, and from the work on the farm. You know, that lion you can hear now …’

‘Yes?’ George said.

‘If it comes into camp tonight it’s not going to bite you …’

‘Good.’

‘… it’s going to eat you!’

3

‘Let me see Kenneth Ngwenya,’ Paul said to Chief Inspector Harold Hayes.

The police station smelled of sweat and urine. Paul felt as though he wanted to be sick. He hadn’t slept and had hardly eaten, save for some gruel-like soup at the hospital. After flying from Kariba to Salisbury he’d hitched a lift to Bulawayo on a delivery van. He’d arrived in Bulawayo late the night before.

Pip was in the intensive care ward. She’d suffered bleeding after her fall, and some cuts and scrapes from the pavement. Kenneth, according to Pip, had tripped as well and then lain on top of her to try to protect her from being trampled by the fleeing demonstrators. But that hadn’t stopped the police from arresting him. As soon as he was certain Pip was all right, Paul had come straight to the police station.

‘You’re not his lawyer, and you’re not family, so no dice.’ The policeman folded his arms and rested both of his chins on his chest.

Paul glared at Hayes. The two men loathed each other and Paul would have been very happy to live out the rest of his days without ever seeing the fat policeman again. Paul wondered if he’d got the term ‘no dice’ from an American movie or a crime novel. Either one would have radically improved his knowledge of policing and the law.

‘Philippa says Kenneth wasn’t trying to assault her at the demonstration, so you’ve no grounds to hold him in the cells.’

Hayes snorted. ‘You’ve got no grounds, Bryant, to tell me who I can or can’t arrest and hold.’ He leaned forward over the well-worn timber charge counter. ‘You weren’t born here, you don’t know what these people are capable of.’

Paul was seething, but forced himself to stay calm. ‘No, but my wife was born here and she says there was no assault.’

Hayes stood straight again and shook his head. ‘I don’t get you two kaffir-lovers.’

Paul clenched his fist. He wanted to lash out and shatter Hayes’s nose, but he knew that was exactly what the obese bully wanted him to do. That way he could arrest Paul too.

‘A munt knocks your pregnant wife down in the middle of a subversive rally and you come here begging me to let him out of gaol,’ continued Hayes. ‘Wait a minute. Perhaps this is all a ruse to get me to let him out so that you can donner him good, hey?’

‘We’re not all like you, Hayes. Let me see him.’

‘No.’

‘She won’t make a statement against him. Look, Ngwenya’s boy nearly drowned up on Lake Kariba yesterday. He’s still up there. You don’t want the lad to find out his father’s been locked up on trumped-up charges, do you?’

‘Trumped-up? This is none of your business, or your wife’s, Bryant. Special Branch is on the case now, and it’s out of my hands.’

‘What’s their interest in Ngwenya? As I understand it, he and the others were part of a peaceful demonstration over bus fares.’

Hayes snorted. ‘You weren’t there, I was. If you think that demonstration was about the price of bus tickets you’re more naïve than I thought. It’s about politics – about them thinking they’d know how to run a country. That’s why the Branch is involved.’

‘But what’s Ngwenya done wrong? If my wife doesn’t testify you’ll have no grounds to hold him on a charge of assault.’

Hayes smiled. ‘I don’t care whether he assaulted anyone or not. You see, there’s an operation going on right now in Salisbury and Bulawayo. You’ll be able to read about it in tomorrow’s Chronicle. It’s called Operation Sunrise. A new dawn.’

Bryant had no idea what Hayes was talking about.

‘We’re rounding up the rabble and filth who’d sell this fine country of ours out to the communists and the black nationalists. These people think they can bring Rhodesia to a halt by telling honest, hard-working Africans to walk to work rather than catch the bus. All the leaders of the protests have been arrested, and that includes your friend Ngwenya. I doubt he’ll be filling any young minds with red propaganda for some time.’

‘Can I at least see him?’

‘No,’ Hayes said.

Paul didn’t know what else to say. He’d known for years that Kenneth was active in black nationalist politics, but he’d never heard his friend espousing communist propaganda. Far from it, in fact. Kenneth and his fellow agitators wanted one man, one vote – which would mean, of course, black majority rule in a democratic country.

As a schoolteacher, Kenneth was well educated for a black man, having studied teaching at Fort Hare University in South Africa, but this set him apart from the vast majority of black Rhodesians. Even the most liberal whites Paul knew seemed unified in their belief that while majority rule might be inevitable one of these days, it wasn’t something to be rushed. There was a need for more Africans to become better educated before they were ready to govern their own affairs.

When Paul had put this view to Kenneth the teacher had retorted that this was condescending, racist rubbish. It was the closest he’d ever seen the bookish teacher come to radicalism. ‘Paul,’ he’d said, slapping a closed fist into his palm, ‘can’t you see that this will never happen? Our junior education system might be one of the best in Africa for African people, but as long as we are excluded from higher education and so many professions we will never be given the chance to advance ourselves and take control of our destiny.’

Paul thought of Winston, and the high hopes Kenneth had for his son. He still hadn’t worked out when or how he would get back to Kariba to collect the two boys. He hoped they were safe. They were level-headed enough youngsters, but two teenagers together could get up to a good deal of mischief.

‘I’ll get Kenneth’s wife and bring her here. Surely you’ll allow her to visit him,’ Paul said to the policeman.

Hayes nodded. ‘We’re not uncivilised, Bryant. I dare say the black communists wouldn’t be so accommodating to political prisoners if they were running the country.’

The phone rang and a white constable sitting at a desk behind the charge counter picked up the Bakelite handset. ‘Mr Bryant, is it?’ the constable interrupted.

‘Yes.’

‘It’s the hospital, sir. Matron says you’re to get back there now. It’s your wife. She’s gone into labour.’

*

Paul sat by Pip’s bedside in the Mater Dei hospital in Hillside until at last her eyelids fluttered and she opened her eyes.

He kissed her cheek.

‘Where’s George?’ she asked, still groggy from the anaesthetic.

‘He’s fine. Probably having the time of his life up on Kariba with Winston and without me. We have a daughter.’

Doc Hammond had told him the delivery had not been without complications. Pip had lost a lot of blood and had needed a transfusion. According to the doctor, their daughter seemed as healthy as could be expected for a premature baby.

‘Oh, yes. I remember now.’

He laughed, but stopped when she tried to join in and he saw her wince.

‘Go get her, Paul.’