6,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

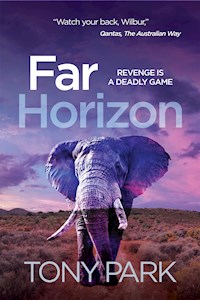

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

An overland tour through Africa becomes a quest for revenge.

Mike Williams is leading a supposedly carefree life as an overland tour guide in Africa, but he's carrying a burden of grief from his time as a United Nations landmine clearer in Mozambique.

The South African police are hunting murderous poachers and they call on Mike to help them investigate a new lead in an old crime whose circumstances Mike knows all too well.

British travel journalist Sarah Thatcher is along for the ride, with a bunch of fun-seeking backpackers, but Sarah is hungry for a hard news story and she'll do anything to uncover Mike's secret past.

Their safari holiday is about to turn deadly.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

About Far Horizon

An overland tour through Africa becomes a quest for revenge.

Mike Williams is leading a supposedly carefree life as an overland tour guide in Africa, but he's carrying a burden of grief from his time as a United Nations landmine clearer in Mozambique.

The South African police are hunting murderous poachers and they call on Mike to help them investigate a new lead in an old crime whose circumstances Mike knows all too well.

British travel journalist Sarah Thatcher is along for the ride, with a bunch of fun-seeking backpackers, but Sarah is hungry for a hard news story and she'll do anything to uncover Mike's secret past.

Their safari holiday is about to turn deadly.

For Nicola

Contents

Prologue, South Africa, 2004

‘Theron needs to speak to you.’

The voice on the other end of the mobile phone was South African. Normally its tone was friendly, jovial.

The man driving the truck said nothing, but swung the steering wheel hard, one-handed, to the left, bringing the bright yellow Bedford to a halt on the grass verge of the road.

He said nothing despite the flurry of questions.

‘What is it? Did you see something?’ asked one of the tourists from the rear cab. ‘Why have we stopped?’

‘Mike? Are you still there, Mike?’ Rian de Witt said into the phone from his office in Johannesburg, four hundred kilometres away.

The driver ran his free hand through his long, dark hair, until it stopped at the band holding the strands in a ponytail. On the other end of the phone line he heard an ambulance siren in the background that brought back memories of the hospital where she worked. As his mind raced he stroked his bristly jawline. Anything to stop his hands from shaking.

He looked out across the expanse of dry yellow grass, the plain spotted here and there with stunted, thirsty acacias. A bachelor herd of impala rams grazed a hundred metres off to the right. They barely paid any notice to the garish overland tour vehicle or the chatting passengers.

‘Yeah, I’m still here,’ he said. The accent was from half a world away, maybe softened a little after more than a year’s absence from his native Australia.

Michael Williams was there in body, but his mind was across the border again, out past where the little antelope were grazing, over the Lebombo Hills that marked the border better than any line on a map. He was thinking of Mozambique.

‘Where are you?’ Rian asked, knowing what was going through the Australian’s mind. Worrying.

Another pause. ‘Mike?’

‘Kruger. I’m still in the national park. Up north. Near Punda Maria. Mobile phone’s only just come back into range again. What do you mean Theron wants to speak to me?’

‘He didn’t say, but he said it was urgent.’

Sarah Thatcher, a blonde-haired woman in the front passenger seat, realised the tour guide hadn’t stopped because he’d seen a lion or an elephant, or a leopard. This was personal. Sarah’s instincts were aroused. She reached for the notepad in the side pocket of her daypack, flipped it open and wrote the word ‘Theron’ on the blank page, shielding it from his view. It might be nothing, but the way the colour had drained from Mike’s face suggested the opposite.

He was normally so bloody laid-back. But she had been trained to observe and now saw how his shoulders were bunched and knotted, like a big cat tensing before a final leap. His stocky frame was tensed, the muscles on his nut-brown arms clearly defined, the khaki T-shirt blotched dark with sweat. Something in the truck’s big diesel engine tick-ticked as it idled.

He said it wasurgent. Mike felt his pulse rate climb. His left hand gripped the steering wheel now, so hard it started to hurt. The mobile phone felt like it might shatter in his right hand.

‘When? Where?’

‘You’re supposed to be crossing from South Africa into Zimbabwe tomorrow. You still on schedule?’ Rian asked.

‘Yeah.’

‘He wants you to report to the South African Police post at Messina, at the border crossing, tomorrow morning. I gave him your schedule and he said he’d meet you there.’

A hundred possible reasons. But why the urgency? ‘OK.’

‘Mike?’

‘Yeah?’

‘Are you really OK? Is everything all right, man?’ ‘I’m fine, the passengers are fine, everybody’s fine,’ Mike said, trying to sound relaxed.

He’d run away from the horror, changed his life, but he hadn’t run far. Maybe, he told himself, he’d stayed in Africa because one day he might get a call like this one. He hadn’t heard from the detective for a year and had nearly given up hope that he ever would. Or, he wondered, had he started to hope the call would never come?

The faces, the places, that lived in his nightmares had grown dimmer and appeared less frequently as the months marched on, but now, as he said his goodbyes and switched off the mobile phone, they leapt back into horrible focus.

Twelve Months Earlier

1

‘I am dying, Michael,’ Carlos said. He folded the single sheet of cheap notepaper carefully in half, then placed it on the smoking embers of the campfire, next to the blackened kettle.

The day was warm already, even though the sun was only just emerging, red and threatening, above the tree line. The sun can be merciless at the end of the southern African dry season.

Major Michael Williams – he preferred Mike, but Carlos was always so damned formal – swilled a mouthful of lukewarm water from the plastic litrebottle. He paused, just for a moment, before swallowing it. He felt ashamed, but he couldn’t help wondering if his friend had drunk from the bottle as well.

Both men watched in silence as the paper slowly wilted and began to smoulder. The Australian tried to think of something to say that wouldn’t sound pathetic. ‘There are drugs. We can get them through the UN. You can live … for years.’ He knew he had failed as soon as he uttered the words.

Carlos dipped into the breast pocket of the sweat-stained blue two-piece overalls that the African civilian United Nations de-miners wore in the field, and pulled out a crumpled packet of Zimbabwean Newbury cigarettes, the remnants of a carton Mike had bought him on his last leave. At fifty cents a packet there are few economic incentives to quit smoking in southern Africa. Carlos reached across, rising from the jerry can of diesel on which he was perched, and offered Mike a smoke. The army officer accepted, flicked open his Zippo and lit both cigarettes.

‘This is Mozambique, not Australia or America. I am finished,’ Carlos said, then dragged deeply on his cigarette.

He coughed as he exhaled. His cough had been bad for weeks and was getting worse. His eyes were deep in their sockets, his ebony skin stretched much tighter across his cheekbones than it had been when the two men first met in Maputo, five months ago.

They had been late leaving Maputo, the Mozambican capital, the day before and Mike had grabbed their unopened mail on the way out of the office. He had stuffed the letters in his daypack and had only remembered them this morning. He was sure they both knew when he handed it to him over breakfast what was going to be in Isabella’s letter to Carlos.

Mike reflected that it had been he who urged Carlos to see Isabella for a check-up and a blood test. Now that the news both men dreaded had finally been delivered, he couldn’t help feeling somehow responsible.

‘I have the virus, Michael.’ The smoke from the burning letter had obscured his face for a second or two. It was a tough enough admission for any young African male to make.

Mike had seen the condom advertisements and the billboards pushing monogamy, but it was all too little, too late. Every day the newspapers carried another story about AIDS orphans, anti-retroviral drugs and statistics. The statistics and projections were mind-blowing, almost unreal. Carlos was real.

The birds were coming to life as the sun turned the butterfly-shaped mopani leaves on the dense thickets of trees around them from pink to ochre, to gold. Despite his friend’s terrible news there was still promise in the new day for Mike.

He thought of his own letter from Isabella as he prodded the fire with a rusted tent peg and then topped up the two coffee mugs with hot water from the kettle. Mike’s note was on the same cheap hospital stationery, but its message, unlike Carlos’s, was a lifeline.

‘What does your letter say?’ Carlos asked.

‘Not much,’ Mike lied. ‘She’s going to be at Mapai in a day or so. I was hoping to meet her there, but now …’

‘I am not going to die today or tomorrow. You do not have to stay with me every minute.’ White teeth lit his broad black face as he forced a grin for his friend’s sake. ‘I will take you there when we have finished surveying the minefield and you can travel back with her if you like,’ he said, waving his cigarette in a vaguely Latin gesture to indicate the matter was solved.

Mike was excited because of his news, and, as a result, also felt guilty. ‘We have to talk,’ Isabella had written in her spidery, barely decipherable doctor’s hand, adding the date and time she expected to arrive at the mission clinic in Mapai, where she did volunteer work once a month. Perhaps, he mused, it was the confirmation of Carlos’s illness that spurred on his thoughts. Whatever the cause, he now knew what he had to do, what he had to say to Isabella. Carlos was a good ten years younger than he was. A strong, articulate, educated young African man in his prime, who spoke more languages than any army linguist Mike had ever met. He had been a university-educated teacher before he became a soldier. Currently, as a civilian employee of the United Nations, he oversaw people who dug in the dirt of Mozambique for landmines. Now he faced a death sentence. Life shouldn’t be this fucking hard, Mike said to himself.

‘The doctor, she is the one for you,’ Carlos said. He smiled, but Mike could see sadness in his dark eyes. Carlos turned his glance to the dying fire and flicked his cigarette into the hot ash.

Mike stood, shrugged off the faded grey T-shirt he had slept in and fetched his mottled camouflage shirt from the front seat of the Nissan Patrol. He ran a hand through his close-cropped hair and then buttoned the uniform shirt as he walked, trying to ignore the smell of stale smoke and dried sweat. He brushed a smear of dust from the circular blue and white embroidered United Nations roundel stitched to the armband on his right sleeve. Below the UN badge was an Australian flag and his country’s name, stitched in white cotton. He was, as he realised every day, a long way from home. He scratched the stubble on his chin and decided that as he was in the bush he could forgo a shave for one day. Mike walked around to Carlos’s side of the fire and laid a hand on his shoulder.

‘We’ll see Isabella together. She’ll tell us what you need and we’ll get it. I’ll see to it, mate.’

Carlos didn’t look up, and Mike removed his hand. The remains of their half-eaten breakfast, tinned herrings in tomato sauce wrapped in pao, the locally baked bread, sat cold and unappetising on a plastic plate on the upturned Manica beer crate that served as their table. Mike grabbed the last of the paoand shovelled the oily mess into his mouth. ‘Let’s go,’ he said between swallows.

‘I do not want to endanger your life, Michael,’ Carlos said as the Australian busied himself loading their meagre camping stores and bedrolls into the back of the Nissan.

‘Pass me the gas bottle. You’re not going to endanger my life unless we start kissing, mate,’ Mike said, in a lame attempt at lightening the sombre mood.

‘You know what I mean.’

He was hinting at what all of them feared, deep down inside. All of those involved in the dirty, back-breaking task of cleaning up the remains of other people’s wars. If one of them stepped on a mine, the other would have to treat him. There would be blood and there would be saliva and vomit.

‘No, Carlos, don’t worry about it,’ Mike said. ‘We’ll see it through.’ Mike knew this was an easy statement for him to make, as he only had a month left to run in Mozambique of his posting with the UN Accelerated De-mining Program. After that, he would be off home to Australia. Or maybe even to Portugal with Isabella, if things worked out.

‘Right, let’s get to work,’ Mike said.

Carlos nodded and drained his cup. They loaded the jerry cans and climbed into the Nissan for the short, bumpy trip from their bush campsite along a track one of the UN teams had been clearing of antipersonnel mines. The team had been called away two days earlier to destroy some mortar bombs found in a small village north of Mapai. They should have been back by now, but it had turned out the bombs were just the first items in a big cache of ammo left over from the civil war days, and they had been delayed.

Carlos and Mike had been warned that a party of politicians and journalists were going to be visiting their AO – area of operations – in a week’s time. They had been tasked by Jake, their supervisor, to find some accessible places where they could safely show the VIPs what the UN teams were doing.

‘All this for a PR stunt, eh? What a joke,’ Mike said as he drove. Carlos stayed silent. Despite his complaining, Mike knew that glad-handing politicians and babysitting journalists was an important, if sometimes painful, part of their job. The recent pace of international events had taken the world’s attention away from UN backwaters like Mozambique and the de-miners knew they were fighting for every cent of funding from a shrinking budget. The more publicity they could generate about their work, the greater chance they had of staying in business until the job of mine clearing was finished once and for all.

Carlos’s silence unnerved Mike. Normally the African was chatty, and ordinarily Mike would have been grateful for the respite. He hated mornings. Today, though, he craved his friend’s banal questions about life in Australia and the other countries he had visited, or his musings on the league table of African soccer teams, which interested the Australian about as much as the game itself. Mike busied himself by turning on the Global Positioning System receiver mounted on the dashboard and watching the clever little gadget acquire a signal from three orbiting American satellites somewhere in space.

It was seven o’clock when they arrived at the track junction, where the mine-clearing team had stopped work before being called away. Carlos and Mike had arrived in the area the previous evening, but it had been too dark to carry out their inspection. They had camped overnight in the bush nearby.

Mike stopped the truck and pulled out the largescale map of Mozambique from between the driver’s seat and the console, and then pushed the mark button on the GPS. This gave him a readout of their position on the earth’s surface, in latitude and longitude. He wrote down the coordinates in his green hard-covered army-issue notebook.

‘Twenty-three degrees, twenty-seven minutes south, and thirty-one degrees, fifty-five minutes east. We’re slap-bang on the Tropic of Capricorn,’ he said, pointing at the first row of numbers on the screen. Carlos smiled politely, but said nothing.

There were no recognisable features in the dense mopani forest, but somewhere a few kilometres to the west of them was the border with South Africa and, on the other side, the world-famous Kruger National Park. About a hundred kilometres to their north, and slightly west, the borders of South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique all converged. On the South African side, opposite where they were plotting the minefield, was one of the highest densities of wildlife in the world, but in Mozambique, the bush was all but devoid of large mammals.

They stayed seated in the Nissan, the engine ticking over in order to keep the air-conditioner running. ‘Bloody shame to think about all those rhinos and elephants and everything else that used to be here,’ Mike said, as he surveyed the bush around them.

‘People starved during the civil war – and after it. They had to eat,’ Carlos replied, not meeting Mike’s eyes as he spoke.

Mike knew that the local people had snared and shot game to feed themselves, but others had turned to the poaching of bigger game, such as rhino and elephant, out of greed. He said nothing, though.

The only sign of wildlife Mike had encountered in Mozambique, apart from snakes and baboons, was the eerie whoop of the hyena, which could occasionally be heard in the bush at night. Recently, however, he had read that the fence on the South African border had come down and there was now nothing stopping all manner of dangerous creatures from wandering into areas like the one they were visiting, where their teams had been clearing mines.

Mike checked the map again. The area where they were working, an old hunting concession named Coutada 16 by the Portuguese, was to become part of a peace park or, to use the technical name, a transfrontier conservation area. The peace park concept, he thought, was a good one. It envisaged cross-border national parks where animals could migrate freely and safely across Africa’s international borders, and well-heeled tourists could pour millions of dollars into bankrupt economies. One of the envisioned ‘super parks’ would unite the Kruger park with Coutada 16, along with Gonarezhou National Park in Zimbabwe to the north. A great idea, but there were many obstacles to overcome before it would ever become a reality. Like landmines, for instance.

‘Someone’s taking this peace park thing seriously, otherwise why would we be clearing bush in the middle of nowhere?’ he asked rhetorically.

‘At times I never thought I would live to see peace in my country,’ Carlos said as he wound down the window and lit a cigarette. ‘You think it is sad about the animals, and it is, but think how cruel man is to man as well. Look at the landmines and the bombs we uncover. From all over Africa, from all over the world. First the Rhodesians chasing the Zimbabwean nationalists around our country – mining, bombing, shelling. Then the South Africans and RENAMO fighting us in FRELIMO. Landmines and bombs from Russia, Germany, Czechoslovakia, England, Portugal, South Africa …’

Mike said nothing, just nodded. He sensed the sad realisation that was sweeping over his friend, the bitter irony that he had survived so many years of war only to be struck down by an avoidable disease. Though still poor, Mozambique’s fortunes had grown year by year since the end of the civil war between Resistencia Nacional Mocambicana, the Mozambique National Resistance, or RENAMO, and the Frente de Libertacao de Mocambique, the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique, known as FRELIMO. Former fighters from both sides had been working together to rebuild the country since the first multiparty elections in 1994, and while Carlos had lived to see his country at peace, he would not see it prosper.

When Carlos had finished his cigarette, Mike said, ‘Remember, we’re just here for a recce, OK? I want to make sure it’s going to be safe enough to bring the politicians and the media this far into the bush.’

‘I think you are impatient for your doctor’s appointment, yes?’ Carlos said with a wink.

Mike was pleased to see Carlos’s spirits lifting, even if his levity was laboured.

Their local guide, an elderly Mozambican called Fernando, came into view, walking around a bend in the track. The de-mining team working in the area had praised his knowledge, eyesight and good humour.

Carlos got out of the Nissan first and spoke to Fernando for a while in Portuguese, the common national language of their former colonial masters. He translated the gist of their conversation for Mike. ‘He was a park ranger before the war, working for the Portuguese. Then he worked as a hunting guide in Coutada 16 and now we pay him.’

Mike guessed his age at somewhere between fifty and seventy. Fernando had a cap of tight frizzy grey curls atop a face as weathered and lined as elephant hide. He had two teeth left in his top row and none in his lower jaw that Mike could make out. He was dressed in the tattered remnants of his old khaki National Parks uniform. His shirt was patched in several places and his shorts were frayed and held up with a knotted length of twine, but creases showed where both had been neatly ironed.

Fernando straightened his wizened body and saluted Mike as he stepped down from the Nissan. Mike noticed that the AK-47 at his side was obviously cared for by him as lovingly as his tattered uniform was by his wife. The rifle was probably as old as his clothes, but, like them, still did the job.

‘Bom dia, Major,’ he said. Mike returned his salute and the greeting.

Carlos and Mike left the Nissan and followed Fernando along the course of white plastic tape the clearance team had strung out to trace the cleared section of the minefield. Mike recalled from the team’s initial report that the mines they had so far found were antipersonnel, Russian-designed and made in Poland in the 1970s. Nasty little bastards designed to take off a foot or shatter a leg below the knee.

Mike looked up and down the track and stroked his jaw thoughtfully. He wondered if he could usher twenty or thirty civilians, including pushy photographers and television cameramen, along the narrow path without any of them stumbling over the white tape.

‘Mike, over here,’ Carlos said. He was down on one knee, at the extreme end of the cleared path next to one of the metal stakes that supported the white tape marking the corridor. He had a twig in his hand and was gently scraping the dirt in front of him.

‘What is it?’ Mike asked. ‘PMN 2.’

Carlos got down on both knees now, lowered his head and gently blew the dust away. The smooth round pressure plate of the antipersonnel mine was gradually revealed.

‘Nasty,’ Mike said. ‘Whichever of our guys drove the last stake into the ground didn’t know how lucky he was.’ The rusted metal picket was only centimetres from the mine.

‘I’m going to lift it,’ Carlos said, looking into Mike’s eyes.

‘No. Mark it and let’s move on.’

Carlos held Mike’s stare and shook his head. ‘We can’t leave it here, Michael. You know that. It is a hazard to our men, let alone the dignitaries.’

‘Carlos, we’re desk jockeys, for Christ’s sake.’ Both Mike and Carlos were trained de-miners, but their task as senior members of the UN mission was the planning of operations, not digging in the dirt. Mike’s unvoiced concern was Carlos’s emotional state in the wake of the news he’d just received. On the other hand, he wanted to convince Carlos that he still had a future with the UN team, despite his illness.

‘All right,’ Mike said, ‘but at least let me get your protective gear.’

*

Mike checked the heavy diver’s watch on his wrist. It was already nine. ‘How’s it going?’ he called across to Carlos. Again, he felt guilty that he’d been lost in thoughts of Isabella – her perfume, her dark eyes, her slender legs beneath a short denim skirt – as he sat on the fallen log, smoking, while Carlos worked.

Carlos had found a second mine near the first and insisted that he should disarm that one as well. It was still in the ground in front of him, but he had cleared the soil from the pressure plate.

‘Almost finished, but I am getting too old for this business, I think.’ Carlos straightened his back, rose up on his knees and undid the Velcro fastenings of his armoured vest to let the air through to his chest. He raised the clear protective visor of his blue helmet and wiped the sweat from his face.

As Mike started to rise he heard a soft tap tap behind him, and froze.

He looked back over his shoulder and saw that Fernando had stopped dead-still in the centre of the cleared track. He was tapping the tin magazine of his AK-47 with a finger to get their attention. The barrel of Fernando’s rifle was now pointed towards the bush to Mike’s left. The old man was sniffing the air, his broad nose wrinkling in distaste.

Carlos and Mike did the same. Mike smelled its pungent, musky, dirty-washing odour, then heard the telltale crack of splitting wood as it ripped a branch from a tree.

‘Elefante,’ Fernando whispered.

Fernando began to move forward, but Mike placed a firm hand on his iron-muscled calf as he drew alongside him. Mike pointed across to the ground in front of Carlos, indicating the mine the other man had just unearthed. Fernando nodded and stood his ground.

They could all hear the beast clearly now, snapping off branches from a tree somewhere in the bush, maybe forty or fifty metres away. Mike held his breath and craned his neck for a glimpse. It sounded to him like there was only one.

The local newspapers and television news had carried a story the week before about how the South African National Parks Board was relocating elephants across the border from Kruger, to build up the numbers of big game on the Mozambique side of the peace park. But the relocation, according to the media, was happening a fair way north of where the deminers were working.

Perhaps the one they could hear now had strayed across the border on his own, Mike mused, or maybe he was a local boy, a survivor of twenty years of poaching and war. If the latter were true, he would know man only as an enemy.

The stillness of the moment was shattered by the crack of a heavy-calibre rifle shot, followed immediately by a tormented trumpet blast of pain. All three men dropped instinctively to the dirt, but Fernando recovered first, his old instincts guiding his movements. He stood and strode three paces so he was in front of Mike, and brought his AK-47 up to his shoulder.

The big-bore rifle thundered again, close by, and Fernando was punched backwards over the top of Mike. Both men sprawled in the dust. Mike lifted the Mozambican off his leg and stared into the horror that was Fernando’s face. The bullet had entered his right eye and blown away the back of his skull. His mouth was wide open and his remaining eye stared fixedly, lifelessly at the sky.

‘Carlos, the sat-phone!’ Mike hissed urgently as he leaned across Fernando’s body and grabbed the guide’s fallen Kalashnikov from the dust.

Carlos nodded, understanding that Mike wanted him to get back to the Nissan, but then he hesitated. From in front of them came another pain-crazed trumpet blast from the wounded elephant. The earth pounded like a rolling quake beneath them and they heard branches breaking. The bull was coming their way.

Mike fumbled with the unfamiliar safety catch on the Russian assault rifle and, still crouched, fired a burst of three rounds on full automatic towards the direction the rifle shot had come from. He aimed low, guessing correctly that the automatic rifle would pull high as he fired the burst. The rifle butt thudded into his shoulder. The acrid smell of cordite burned his nostrils. His heart raced and he suddenly felt like throwing up.

‘Scheisse,’ Karl Hess whispered to himself.

The elephant was wounded, but not fatally; Hess’s client, the bloody Russian, was cursing aloud, too loud, and now he had spotted a black ranger about seventy metres away. The ranger had been crouching but he started to stand. Hess didn’t think the man had spotted him yet, or else he wouldn’t have risked standing, but now the figure in his telescopic sight was raising an AK-47 to his shoulder. The blacks, goddamn them, had excellent eyesight, and Hess knew he would be spotted in a couple of seconds. The other two members of his party, his African servant Klaus and a local Mozambican tracker, crouched behind a tree, watching the hunter intently.

Hess breathed in, watching the crosshairs of the sight rise slightly above the man’s wide ebony forehead, then let out half a breath. As the aiming point fell slowly back into place, down over the frizzy grey hair and into the centre of the ranger’s forehead, Hess squeezed the trigger. The action was as natural to him as breathing. Hess registered no emotion as the rifle thudded into his shoulder. The black man’s face disappeared in a spray of blood.

Killing was Karl Hess’s profession and he was very good at it.

Some professional hunters he knew tried to romanticise their job. These men claimed they respected the animals they hunted and felt a kinship with them. They even tried to convince others that what they were doing was all part of the delicate balance of conservation. Rubbish, thought Hess. He had about as much respect for the elephant his client had almost killed as he did for the black man he had just wasted.

The client. Scheisse. In truth, he didn’t mind the Russian and had even grown to like him a little in the past few days. He could feel some ‘kinship’ with the man, even although they had fought on opposing ideological sides in different battles of the Cold War. Respect him? No – he had yet to meet a client worthy of his respect, but he did quite like him. Now he just wanted the man to shut up. He raised a finger to his lips, although it was unnecessary now, as the Russian had stopped his whining when he heard the report of Hess’s rifle.

‘Get down,’ Hess said.

The Russian obstinately remained standing, staring in the direction where Hess had just fired. Hess shook his head in frustration, but continued peering through the mopani trees. He couldn’t understand what the man in the tatty ranger’s uniform was doing there. Poaching, perhaps?

‘The elephant?’ the Russian whispered in English, the only language they had in common.

Hess shook his head again, raising a finger to his lips to motion the Russian to silence. The elephant was the least of their worries now. He would call the helicopter when he was ready and they would follow it from the air until it tired or died.

Both Hess and the Russian heard the metallic rasp of an AK-47 being cocked. They had been around that weapon for too many years to mistake it for anything else.

Pop-pop-pop. That was the thing Hess always found faintly amusing about the Kalashnikov: its rattling report, similar to a coffee percolator, belied its gruesome efficiency as a weapon. Leaves shredded around him and he felt a whoosh of displaced air past his legs. The shooter was firing blind, on full automatic, but he was firing low, which was dangerous.

Hess dived for the dusty earth and rolled towards the thickest tree he could see. The idea was to get out of sight of the enemy and, when you were ready to fire back at him, to do so from a place of cover, as far away as possible from where he had last seen you. Hess did not panic, for he never panicked in battle, but he did swear quietly again when he heard the Russian cry out in pain in his own language.

To his credit, the Russian did not scream or moan after that first yelp, and this, despite the man’s stupidity at not seeking cover when Hess had originally instructed him to, helped stop the man’s stocks from falling any lower. Hess leopard-crawled to the Russian, keeping his rifle out of the dust in the crooks of his outstretched arms.

Major Vassily Orlov was wounded, in the leg, and it hurt like the devil. Orlov was no longer a major in the Spetsnaz, the Russian Army’s elite special forces, but he still liked people to address him by his former rank. It lent an air of legitimacy, he thought, to his business dealings, and reminded those who traded with him that he was not some Moscow street punk or a common pimp.

He was wounded, but he had no intention of dying in the wilds of Mozambique. Orlov had too much money to die like some ragged third-world rebel from a wound inflicted by a rifle manufactured in his own country. He had paid the Namibian, Hess, a small fortune to get him here, but, as Hess knew, he would forfeit the substantial amount still owing if he failed to get Orlov his trophy, or if the Russian died in the process. One thing Orlov had learned in his new career as a businessman was that one could always trust in the power of money. Ideologies, regimes, politicians all came and went, but no one turned his back on cash.

Orlov’s new safari trousers were ruined. They were olive green, with detachable lower leg sections that zipped off to leave knee-length shorts. Above them he wore his old Spetsnaz camouflaged smock. He acknowledged Hess’s concerns about being seen in military attire in the African bush, but countered them by stating the obvious – that there would be trouble if they were seen, whatever they were wearing. Like many old soldiers, Orlov was faintly supersti tious and he had worn this same smock on every operation he had been involved in. He regarded it as his good luck talisman.

Judging by the wound, it was probably a ricochet that had hit him in the lower leg. The bullet had glanced off a rock, perhaps, and ploughed into his right calf. Orlov gingerly touched the skin around the entry wound, a neat round hole ringed with dark burnt flesh. He winced as he touched his shinbone. The bullet had hit the bone and, its force nearly spent, had tumbled to rest higher up the calf, near the knee. He knew he was in shock and that the pain would soon come in earnest.

He pressed down on the entry wound, using his palm to staunch the oozing blood. The wound was a bad one because the bullet was still inside him, but Orlov doubted it was life threatening.

He had been shot once before, in Afghanistan, by a sniper, but that was in the upper arm and the bullet had passed cleanly through. His men had caught the sniper later – he was little more than a boy, maybe fourteen or fifteen, with a wispy moustache and beginnings of a beard. Orlov’s men had wounded him in a short firefight and managed to capture him – the Mujahideen would never surrender of their own accord. They dragged the wounded teenager into the village square by his long, filthy hair. Orlov shot him in the head in front of his wailing family and the rest of the village.

He sat with his back to a tree, legs spread wide and his rifle resting on his good leg. The gunfire had stopped now and he wondered about the elephant. The animal had been every bit as magnificent as Hess had described it. Orlov had hunted ever since he could remember. His father had taught him to follow tracks, both in snow and on bare ground. They had started with deer and, eventually, graduated to bear. Later in life Orlov had several opportunities to indulge in the ultimate hunt, man against man, in the service of his country.

In Afghanistan, in addition to his military duties, he had begun his business career, starting with hashish and graduating to heroin. He would never indulge in the drugs himself, although some of his men and even his fellow officers had. The vast profits to be made, and the growing lack of confidence he had in his country’s rulers as a result of the war, had turned him from soldier to entrepreneur. Now his business interests reached far and wide, across Europe, Asia, the Americas and Africa. Orlov was an importer and exporter – drugs, cars, women, girls, boys, art, animals, weapons, diamonds were all commodities that had passed profitably through his hands. He wanted for nothing in terms of material goods and women, but what he missed was the thrill, the danger and the rewards of his days as a soldier.

An interest in diamonds had brought him to Africa and he had indulged his passion for hunting at the same time. He soon tired, however, of a succession of professional guides who treated him either as a dolt or a cash cow. He had been offered paltry trophies – drugged cats or ancient animals on their last legs. During a trip to Miami in Florida, however, a Cuban businessman, another former army officer and a fellow shooter now living as an exile in the United States, had recommended someone to him. A special hunter who knew what discerning clients wanted and how to circumvent certain regulations, if that was what was needed to satisfy his customers. Ironically, the Cuban believed he may have even fought against the man, who had served as an officer in the South African Defence Force, in Angola.

Orlov was redecorating his dacha in the countryside outside of St Petersburg and wanted an African big-game theme. He could have bought the trophies he had in mind, but he would never be satisfied with other men’s prizes. He had arranged a meeting with Hess during his very next business trip to South Africa and, from the outset, had been impressed with the man. Orlov thought the hunter was a cold individual, who would stop at nothing to get what he wanted. Perfect.

Hess knelt before Orlov now, not the slightest emotion clouding his face as he ran his fingers along the Russian’s wounded leg. ‘It has hit the bone – it may be fractured,’ he said brusquely. ‘Exit wound?’

‘Nyet,’ Orlov replied.

Hess drew a hunting knife from a pouch on his belt and quickly sliced open the bloodstained detachable lower half of the trouser leg. Next he took Orlov’s rifle from his lap and ripped the combat field dressing from the wooden stock, where he had taped it prior to their setting off from his lodge across the border. Hess carried an identical dressing taped to his own rifle, but, as in combat, he used the casualty’s dressing to treat him. He tore open the waterproof packet with his teeth, unfolded the big sterile pad, and pressed it over the wound. He wrapped the long bandage tapes from the dressing around Orlov’s calf and tied it off.

From the bush where his shots had fallen, Mike Williams heard a man cry out in pain, but in a language he couldn’t place. Not English, not Portuguese, not Afrikaans. It didn’t matter.

The elephant burst from the bush onto the open track, not thirty metres from where Carlos and Mike crouched, near the fallen Fernando. It was definitely a bull – Mike could tell from the shape of its oversized, rounded, knobbly head. Females, he had learned, have angular, sharply defined foreheads. This one stood as tall as a house and as wide as a battle tank. His legs looked like the scarred grey trunks of the leadwood. The yellowed ivory tusks, each the length of a grown man, curved inwards until they almost met.

Enraged, rather than scared by the sound of the gunfire, the elephant turned and faced the diminutive figures. Mike had learned that normally when an elephant wants to scare an intruder away it flaps its ears out wide and raises its trunk in the air to make itself look as big and as scary as possible. When an elephant means business and is about to charge, it puts its ears back and tucks its trunk in down between its tusks. Which is what the old bull did now.

Mike swivelled and pointed the AK-47 at the elephant, which began its charge. Puffs of dust exploded from the track with each mighty footfall. Mike looked again at Carlos and saw he was still ahead of him, to the right, and out of his line of sight. He pulled the butt of the rifle hard into his shoulder, took a breath and sighted along the barrel, aiming at the massive skull. He doubted the head shots would kill the bull, but hoped they would slow the animal down before it reached Carlos.

He squeezed the trigger. There was one shot, which raised a tiny puff of grey dust on the mighty skull, then the firing pin clicked on an empty chamber.

‘Fuck! Run, Carlos!’

Carlos looked at Mike and smiled. He was silhouetted black against the oncoming cloud of elephant dust as he turned to face the beast. Ahead of him, on the edge of the track, was the landmine he had uncovered but had not had time to disarm. His armoured vest lay in the dirt beside him, where he had placed it just moments before.

He pressed his arms against his sides, as if bracing himself, clenched both fists and fell forward, onto the mine, so that his stomach struck the pressure plate.

The explosion sent up a cloud of dust to more than match the elephant’s wake and set Mike’s ears ringing. Carlos was thrown back into the air, almost upright again, as though he had just belly-flopped onto a trampoline. He fell once more and landed on his side.

The elephant stopped dead – his charge had not yet gained enough momentum to carry him forward onto Carlos’s writhing body. He shook his mighty head, flapped his big ears like ragged flags, and turned and fled into the bush. As he swung around, Mike saw the puckered red and white hole in his side. He assumed the wound had been made by the same weapon that killed Fernando. Fresh blood formed a black stripe down the animal’s dusty grey flank.

Mike stood and ran back up the track to the Nissan, bending at the waist to make himself a smaller target, in case the marksman was still watching. There was nothing he could do for Carlos without a first aid kit. As he ran he snapped the magazine from the AK-47 and confirmed that he was indeed out of ammunition.

At last he made it to the Nissan and fired up the engine. The 4WD bounced and juddered along the narrow track, as he floored the accelerator. The sides of the vehicle brushed against the white tape marking the cleared corridor and eventually a strand caught on the front bumper. The tape snapped as a stake was pulled out of the ground and Mike prayed the wheels wouldn’t set off another mine. He stopped the truck as close as he dared to Carlos.

The mine had been designed to blow off a foot or a hand, not to kill. When a man falls on his belly on a landmine and it tears him open and shreds his vital organs, however, that man is going to die.

But the mine hadn’t killed Carlos outright. He bit into his lower lip to keep himself steady and die like a man. When he opened his mouth to speak, Mike saw the bright blood well from the teeth marks in his lip.

‘Don’t touch me, Michael,’ he warned between ragged breaths.

Mike could smell the blood and the stench from Carlos’s perforated bowel and he knew the man was right about the danger, but still he tore frantically at the field dressing. He opened the big white pad and placed it on Carlos’s abdomen. The dressing barely covered the ragged hole. The pumping blood soaked Mike’s arms to his elbows. The dying man’s intestines were visible and Mike had to swallow hard to keep from vomiting.

‘Shut up, Carlos, you’ll be OK. We’ll get you to Isabella.’ Mike remembered being taught to reassure the patient during his army first aid training. He thought it sounded as ridiculous in real life as it had in the classroom. ‘Carlos, for God’s sake, hang on, mate,’ he cried.

He cradled the African’s head in his lap and grasped his right hand, holding tight. Carlos’s whole body shuddered and Mike looked skywards. He leaned back, slumped against the front wheel of the four-wheel drive, utterly exhausted and soaked with the blood of his dead friend.

Mike sat there for what seemed like a long time, but it was really only a couple of minutes, maybe less. He was stirred from his stupor by the sound of the heavy rifle booming again somewhere in the distance. The noise was farther away than before. It was followed a few seconds later by the pop-pop-popof a burst of fire from another AK-47. He realised there were now two weapons in the area, and men who were not afraid to kill.

The adrenaline that had coursed through him just a few moments before was now seeping away, leaving his limbs heavy and tired. Mike folded the rear seat of the Nissan forward, dragged Carlos and Fernando into the vehicle as quickly as he could, then hauled himself behind the steering wheel. His hands were covered in blood and when he wiped the sweat from his forehead it left a sticky smear. He started the Nissan and reversed up the track, trying not to look at the dead men as he navigated his way back to the main road. Once there he turned right, following the railway line south towards Maputo, nearly five hundred kilometres away.

Some of the flies that had already started to settle on the bodies now hovered around him. Mike felt a clutch of them sucking the blood and sweat from his forehead and pointlessly slapped at them as he drove. After a few kilometres he pulled over, wiped his face clean as best as he could, and fumbled for the cigarettes in the top pocket of his bloodstained camouflage shirt. He lit one with shaking hands.

The flies could still smell death on him. So could he, as he drove on into the blinding heat of the day.

Orlov opened his mouth to speak, but he was stopped short by another gunshot, quickly followed by a muffled explosion from the same direction as the earlier shots from the AK-47.

‘The elephant,’ Hess said. ‘Must have hit a landmine. The tracks in this part of the country are littered with them.’

‘Go and get it for me. Finish it off,’ Orlov said. Despite his pain, the Russian forced a thin smile under his grey-flecked bushy black moustache. ‘Or you can kiss the rest of your damned money goodbye.’

Hess nodded. If the Russian died and he couldn’t get the rest of his money, at least he would have the ivory. The cost of the helicopter had already been covered by the advance payment, so he would not be out of pocket. He stood and motioned to his servant, a tall African man in smart olive drab fatigues who hovered nearby. ‘Klaus, tell that little Mozambican monkey to start earning his money as a tracker and find the elephant for us. He can walk in front of us in case there are any more mines, but don’t tell him that.’ Klaus, whose smooth, broad ebony face marked him as a member of Namibia’s Ovambo tribe, had been Hess’s tracker and gun bearer for many years.

Klaus’s allegiance to Hess dated back to his role as a trusted subordinate during the war of liberation in South West Africa. His unflinching loyalty to the white man had paid off over the years, but while he was wealthy by black African standards, he could never show his face among his own tribe again if he wanted to live to enjoy his wealth. Klaus passed on the orders to the wiry Mozambican tracker. Next, he laid down his AK-47, unstrapped two short axes from side loops on the rucksack he wore and gave one to the tracker. The bright, razor-sharp edge of the axe glittered in the sunlight as the tracker held it close to his eye for a momentary inspection.

While Klaus shrugged back into his rucksack, Hess undid the Velcro fastening of a black pouch on his belt and extracted a compact black GPS unit which fitted neatly in the palm of his hand. He pointed the device towards the sky, switched it on and waited for the receiver to pinpoint their position. When the latitude and longitude flashed up a couple of minutes later, Hess pushed the button labelled ‘mark’ and scrolled through the alpha-numeric display until the letter O for ‘Orlov’ appeared, naming the spot after his wounded client, and entering it in the GPS unit’s memory.

‘Don’t go anywhere,’ Hess said humourlessly. ‘I’ll call in the helicopter once we’ve finished off the elephant. If we can’t find it, we’ll get it from the air.’

Orlov nodded and tightened his grip on his rifle. Hess and Klaus set off, with the middle-aged Mozambican tracker, dressed in tattered cut-off denim jeans and a torn brown T-shirt, leading the way. The tracker paused every dozen or so steps to sniff the air, listen, and check the earth and trees around them for fresh signs of the elephant.

The tracker was leading them away from the direction in which they had heard the explosion and the last of the firing. Hess was aware of not having addressed the problem of potential witnesses, but the elephant had to be his first priority. The tracker held up a hand and all three of them dropped to a crouch. The Mozambican had kept them downwind, and the elephant, now thoroughly disoriented, had wandered into a natural clearing. Perfect, thought Hess, and raised his rifle.

It had been many years since old Skukuza had heard the terrible sound of thunder this close, but he recognised it as the sound of death. The louder noise, the explosion, had thoroughly confused him, though, and he blinked and rubbed his eyes with the tip of his trunk to clear the dirt that had been thrown up by the blast. He shook his big, knobbly head to try to free himself of the pain and looked for another target to vent his rage on. But there was nothing around him and his world was slowly turning a foggy grey.

Hess was behind and to the left of the huge beast. He instinctively aimed for a spot level with the elephant’s left eye, behind the ear, just forward of the vertical line where its front left leg joined the fat grey body. The hunter smiled as he pulled the trigger, knowing the heavy lead bullet would find the elephant’s brain. The rifle boomed and the elephant turned towards them and took a few last valiant steps. Hess stood his ground. The beast sagged forward, onto his front knees, and then toppled sideways, raising an immense cloud of dust, as his back legs gave way. Hess motioned the two Africans forward. There was no way he was going to leave his footprints close to the carcass.

Klaus stepped into the clearing and fired a fourround burst from his AK-47 into the animal’s belly to make sure it was dead. Then he knelt and picked up the spent bullet casings from the dust. He waved for the tracker to join him. Hess left them to the work of removing the tusks, confident that Klaus would ensure the long, curved ivory was not damaged.

Hess strode back through the bush, quickly but carefully retracing his steps to avoid any stray mines in the area. As he walked he lifted the walkie-talkie that hung from a strap at his side and spoke into the mouthpiece.

‘Eagle, this is Leopard,’ he repeated twice into the radio. Their call signs, Eagle for the helicopter and Leopard for the ground party, had been Orlov’s idea. Since the Russian was paying the bills, Hess indulged his unnecessary romanticism.

The pilot, Jan Viljoen, a former South African Air Force lieutenant, finally acknowledged the call. Hess took out his GPS and read off the coordinates for the pick-up spot, where Orlov lay wounded.

‘You’ll need to lower the winch when you get there, I have one man down and the bush is too thick for you to land, over,’ Hess said. Off to his left, some distance away, he heard the sound of a vehicle engine starting. His unseen adversary was getting away, but Hess was relaxed. I didn’t see his face, so I know he didn’t see mine, he told himself confidently.

‘Ja, got it,’ Viljoen replied. He had been circling twenty kilometres away out of sight and earshot of the hunt after dropping Hess and the Russian off in the bush. He was near the border of the Kruger park, staying low and following a herd of buffalo that had strayed across the newly unfenced border into Mozambique. Now, thanks to him, the buffalo were stampeding back to the comparative safety of the South African national park. ‘Watch out for the lions, now, boys,’ he said aloud to himself.

Viljoen felt a pang of regret for the elephant. He had enough love for the bush to know that what they had done was very wrong. However, he, like his former brother-in-arms Karl Hess, was now a soldier of fortune, a mercenary, and money always claimed his first allegiance. His second love was flying, and the Bell 412EP they were letting him play with was a delight.

He dipped the nose and watched the airspeed needle climb as the russet-brown bush whizzed past a scant sixty feet beneath him. He had removed the two front doors from their hinges before take-off to give him better visibility for the close-in work of infiltrating and extracting the team, and the modification also made for a cooler, more exhilarating flight. Viljoen, alone in the machine now, glanced across his shoulder and confirmed that the first aid kit was clipped to the bulkhead where it should be. Hess had a man down, although he didn’t say who, and the old bastard had sounded as calm as you please, as though he was asking Viljoen to pick up some more beer on his way. He wondered who was injured as he punched the coordinates for the pick-up point into his own GPS and set a course for the rendezvous point.

He tested the winch by flicking the appropriate switch and watching the yellow jungle penetrator drop a foot or so on its cable. The device, developed by the Americans in Vietnam, was about the size and shape of a small bomb, suspended by its blunt end from a winch cable. Its pointed nose and weight allowed it to fall easily through branches and leaves, avoiding entanglement. Once on the ground, the men who needed to be picked up unfolded the long sides of the ‘bomb’, which then became seats that two men at a time could straddle.

Orlov’s skin was paler than when Hess had left him, but the Russian was still conscious. Hess checked his client’s pulse. It was strong, which was good, but he seemed to be in a lot more pain. Hess began to lift the blood-soaked pad of the field dressing and Orlov screamed.

Hess was worried. Orlov was ex–special forces and had hardly made a noise when he was shot. Why was he in such pain now? The Russian was biting down on his lower lip and forcing himself to regain his composure. Hess reached out again and lifted the pad. Orlov shuddered and Hess noticed a thin tear escape from the hardened soldier’s tight-shut eyes.

‘It is bad, the pain?’ Hess asked.

Orlov took a deep breath before answering. ‘Worse than it should be.’

Again, Hess lifted the dressing. He shut his ears to the Russian’s yelp and shook his head as he inspected the lower leg. It was swollen to nearly twice its normal diameter, the skin stretched taut as a drum. Hess assumed the wound was bleeding internally.

‘You will be lucky to keep this leg,’ he said matterof-factly.

Above him he heard the low thump of the helicopter’s four blades. Hess shrugged off his rucksack and rummaged inside it. He stood, holding a DayGlo orange marker panel about three feet long by one foot wide. He held the vinyl panel above his head with two hands, his arms outstretched, and made a high clapping motion.

Hovering above the point fixed in his GPS, Jan Viljoen noticed the flicker of orange below him and slewed the big helicopter to his right for a better view. Below him, he saw Hess. He stabbed the winch switch and the jungle penetrator sailed downwards, whining as the cable unwound freely.

Hess stepped back and waited until the blunt yellow cone of the penetrator thudded into the dust and leaves at his feet. He stuffed the marker panel into the half-open front of his bush shirt and shrugged on his rucksack. Before he tended to Orlov he walked a few paces to the point where he had fired at the ranger and, after a few seconds of looking, found the spent brass cartridge case from the bullet. He slipped it into his top pocket.

‘Come on, come on, you bastard,’ Viljoen muttered as he fought to keep the helicopter hovering in one place. A stiff breeze had picked up and it was rocking in the thermal up-drafts of hot air rising from the heated earth.

Hess grabbed Orlov under the armpits without ceremony or care for his wound and hoisted him onto one of the splayed legs of the jungle penetrator. He unfolded the opposite side and took his own seat, facing the Russian. He gave Viljoen an unsmiling thumbs-up, and wrapped his long, muscular arms around Orlov’s neck. With the casualty now obviously secure, Viljoen flicked the winch switch and the pair rose slowly through the mopani leaves, locked in their lovers’ embrace.

Ideally, there would have been a crewman on board to operate the winch from a second set of controls in the cargo compartment of the chopper, and to pull in anyone who needed to be winched aboard once they were level with the cargo doors. The doors weren’t a problem, as Viljoen had removed these as well as the crew doors, but Hess had to start a pendulum motion in order to get a leg onto the left skid so that he could then pull the injured Orlov inside. Hess made the tricky manoeuvre look easy, despite Orlov’s reluctance to ease his grip on the hunter to allow him to do his work. Eventually, Hess had Orlov seated on a canvas webbing troop seat. He fastened a seatbelt around the Russian’s waist, in case he passed out and slumped to the floor or, worse, out the door.

Hess grabbed the back of the co-pilot’s seat and peered out the plexiglass windows of the front cockpit. He pointed Viljoen in the direction of the elephant and noted that the pilot had been sweating, presumably with the effort of keeping the machine in one spot for so long. Hess had an infantryman’s resentment of aviators and their world of comparative luxury, but now, as on several occasions in his life, he thanked the good Lord for flying machines.

Viljoen was about to earn his pay all over again. ‘You are not to touch down, understood?’ Hess barked in the pilot’s ear as he brought the 412EP down towards the elephant carcass. Viljoen acknowledged the order with a curt nod – there wasn’t enough room in the tiny natural clearing to touch down even if he had wanted to.