4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

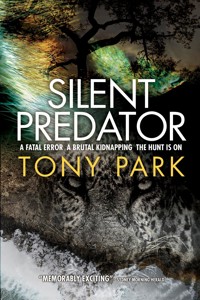

A missing man sparks a chase through Africa to track down true evil.

In a luxury private safari lodge in Kruger National Park, Detective Sergeant Tom Furey has just woken to a bodyguard’s worst nightmare. The VIP in his charge, British Assistant Minister for Defence, Robert Greeves, has vanished.

Knowing his career is on the line, Furey vows not to stop until Greeves is found – dead or alive. He and his South African counterpart, Inspector Sannie van Rensburg, go against official orders and start the hunt for the suspected band of terrorists through the outer limits of the National Park to the coastal waters of Mozambique. Increasingly drawn to Tom, Sannie can’t resist becoming more and more involved in his dangerous mission, even risking her job to help him.

By the time Tom and Sannie discover that their foes are as elusive and deadly as the stealthy predators of the African bush, it is their lives, and those of their loved ones, that are at risk. This is a fight to the death, and involves a crime beyond anyone’s worst imaginings.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

SILENT PREDATOR

TONY PARK

CONTENTS

About Silent Predator

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

More Sannie van rensburg

About Tony Park

Also by Tony Park

ABOUT SILENT PREDATOR

A missing man sparks a chase through Africa to track down true evil.

In a luxury private safari lodge in Kruger National Park, Detective Sergeant Tom Furey has just woken to a bodyguard’s worst nightmare. The VIP in his charge, British Assistant Minister for Defence, Robert Greeves, has vanished.

Knowing his career is on the line, Furey vows not to stop until Greeves is found – dead or alive. He and his South African counterpart, Inspector Sannie van Rensburg, go against official orders and start the hunt for the suspected band of terrorists through the outer limits of the National Park to the coastal waters of Mozambique. Increasingly drawn to Tom, Sannie can’t resist becoming more and more involved in his dangerous mission, even risking her job to help him.

By the time Tom and Sannie discover that their foes are as elusive and deadly as the stealthy predators of the African bush, it is their lives, and those of their loved ones, that are at risk. This is a fight to the death, and involves a crime beyond anyone’s worst imaginings.

For Nicola

PROLOGUE

Today

Tom Furey groaned.

Each beat of his heart sent a dart of pain to his head as his brain tried to break through the bone of his skull. His tongue was so swollen and dry his first thought was that he might choke. He was aware of a bright light shining on the other side of closed eyelids. He opened his eyes and blinked, the small movement eliciting another moan.

There was an almost mechanical noise beside him, like a motor with a faulty exhaust. Snoring. He turned his head – more suffering – and saw the woman lying on her back, mouth agape, her bare breasts rising and falling. The tangle of sheets was across her lower legs. Like him, she was naked.

Daylight.

‘Shit!’

He groped on the side table for his watch and mobile phone. It was six am and the bright African sunlight was streaming in through the sliding glass doors. ‘Shit!’ he said aloud again. Ignoring the ache behind his eyes he swung out of the king-size bed, grappled his way through the ceiling-to-floor mosquito net and hopped on one leg while he pulled on his shorts. He grabbed the mobile phone and checked it. Not only had the alarm not gone off, it wasn’t even set.

Tom buckled his belt and slipped his nine-millimetre Glock 17 into the circular pancake holster above his right hip. He strapped on his watch and checked the time again. Two minutes past six. ‘Shit.’

The weight of his pistol was balanced on his left side by an Asp extendable baton, a spare magazine of ammunition and a Surefire torch, all in black leather pouches. He stuffed his remaining two spare magazines in his shorts pocket, along with his Gerber folding knife. Despite the rush he would have felt naked leaving the room without any of his personal kit.

He pulled on a blue polo shirt and left it untucked so that it covered the equipment, then forced his feet into trainers with no socks. Thank god, casual dress was the order of the day.

With nothing more than an angry shake of his head at the sleeping woman, he barged out the door and along the raised walkway of darkly stained wooden logs that wound through the thick thorny bushes behind and between each of the separate luxury suites of the safari lodge. He paused to knock on the door of the unit next to his. ‘Bernard?’ he called. No answer. Of course there bloody well wouldn’t be an answer. The advisor was ex-Royal Navy. He wouldn’t be late for duty. Tom jogged on.

The morning air was still cool, but the sun was already hot on his face as he glanced out across the Sabie River, its smattering of granite boulders glowing pink in the dawn’s rays. A hippo grunted, mocking him with its deep belly laugh as his shoes pounded the deck.

He slowed to a walk, to catch his breath and maintain some show of dignity as he entered the sumptuous reception area, where early morning tea and coffee and rusks and fruit were laid on a long table beneath the thatched cathedral-style roof.

‘What’s going on? You’re late.’ Inspector Sannie van Rensburg looked at her watch and frowned.

The South African minister was talking to an aide, an empty coffee cup in his hand. He looked at Tom and then beyond him, down the walkway.

Tom motioned her aside with a hand on her elbow. She shrugged off his touch. ‘Where’s Greeves?’ he whispered.

‘That’s what we want to know. Not only are you late, but he hasn’t shown up – neither has his policy advisor.’

He saw the naked disapproval on her face, of him as well as of his tardiness. She must have guessed what had gone on the night before. It was no time to think about what she thought of him. ‘He must be on the phone to the UK. I’ll go and check on him.’

‘I already did that,’ she said. ‘There was no answer.’

‘Why didn’t you come and find me?’ he asked.

‘Ag, I’ve got my own man to look after. I can’t be running around after you, Tom.’ Her Afrikaans accent, which he’d found appealingly exotic at first, grated on his ears. He strode back down the walkway to the suite of the UK Minister for Defence Procurement. Tom prayed that he was right, that The Honourable Robert Greeves was on the phone to his immediate superior, the Secretary of State for Defence, or a senior bureaucrat on some urgent matter of State, and that was why he hadn’t answered the door and was late.

He felt physically sick, but didn’t know why. He’d had only one beer the night before. He came to the third suite, took a deep breath to quell the dizziness and steady himself, and knocked. No answer.

‘Sir? It’s Tom,’ he called.

He waited for exactly a minute and knocked again. Nothing. He pulled out his mobile phone and dialled the minister’s private number. It was for emergencies only, but Tom could feel his pulse rate rising. Straight through to voicemail. He tried the policy advisor’s mobile. It rang out and he heard Bernard Joyce’s cultured voice on the message.

Tom went on to Bernard’s suite, even though he had already tried it once, and knocked on the door. ‘Bernard?’ Nothing again. He thumped harder. ‘Bernard!’

He jogged down the decking to his own unit, opened the door, strode in and called Greeves’s suite. While he waited he saw, through the haze of mosquito netting, the woman still sprawled there. If she was awake she was hiding it. He cursed himself – his weakness. The landline rang out. No answer. ‘Shit,’ he said. ‘Stay cool.’ There was no answer in Bernard’s suite. They weren’t talking on their room phones.

Tom headed back to reception. He ignored the South African policewoman’s enquiring look and went to the duty manager, a young white guy called Piet. ‘I need the key to Greeves’s suite.’

‘But, Tom, man, that’s highly irregular, can’t we just –’

‘Now.’ The man obeyed this time, unquestioning.

Tom forced a smile for the South African Defence Minister, Patrick Dule, who was having a hard time hiding his impatience. Greeves wasn’t the kind to go off with Bernard for an impromptu morning stroll. Tom had learned in a very short time that when a schedule was made he stuck to it, and woe betide anyone who was a minute late.

Tom jogged back to Greeves’s suite. Instinctively, he raised his polo shirt, so that the butt of his Glock was exposed, and easier to draw. ‘Mr Greeves, sir?’ he called again.

He heard footsteps and spun around. It was her. Sannie held up a skeleton key of her own. Great minds, he thought to himself, without mirth. ‘Go to number four – Bernard Joyce’s suite. There was no answer there, either. Let yourself in.’

She nodded. No time for smart-mouthing any more.

He let himself into the minister’s luxurious room. It was identical to his in its safari chic décor and opulence. He took in the signs immediately. The fallen lamp stand, the sheets in disarray, the tangle of mosquito netting on the floor, the bloody palm print on the open sliding door. He drew his pistol. A laptop computer was open, but face down. Greeves’s wallet and mobile phone, switched off, on the bedside table.

Tom moved quickly through the rest of the suite, checking the bathroom and toilet. No signs of the man, other than his toiletries and some clothes in the bathroom. He went back outside and saw Sannie running along the boardwalk.

‘Joyce,’ she panted. ‘He’s gone. Signs of a struggle. It doesn’t look like it was an animal attack.’

Tom shook his head. ‘Greeves is gone too. Wallet full of cash and mobile phone are by the bed, so it wasn’t money they were after.’

‘Oh, dear god,’ she said, and it was more prayer than blaspheming.

And Tom Furey needed all the prayers he could get, because he’d just woken to a protection officer’s worst nightmare.

1

Eight days earlier

‘I need to piss.’

Tom smiled, even though it was too dark in the back of the transit van to see the young constable’s face. He sighed and whispered, ‘You should have gone before we left.’ He’d been waiting for this – as the boy had been fidgeting for the past hour.

‘Yes, Dad.’

‘Watch it, Harry,’ Tom said. He kept his eye on the house, number fourteen, staring at it through the peephole in the side panel of the van. The light was still on in the front room of the nondescript pebble-dashed semi in the quiet Enfield street. He wondered if the neighbours had any idea what was going on behind that green door. They’d be mostly commuters, he reckoned, with safe jobs. Mid-level office workers, secretaries, tradesmen – and they would have a fit if they knew they were living in the same street as a bunch of people smugglers. Someone must have noticed something, though, or they wouldn’t be here. Londoners had been jolted out of their apathy after seven-seven, the suicide bombings on the tube and the buses, and curtain twitching sometimes paid off.

‘It’s only the truth, Tom. You are old enough to be my bleedin’ father.’

‘Perhaps I am. I was in uniform in Islington in the eighties. Your mum ever go to a Bryan Ferry concert?’

‘Now you’re making me sick.’

At the far end of the cramped space, Steve, the civilian information technology expert, looked over the top of his magazine. Unlike Harry, Steve, whom Harry had quietly dubbed ‘the Anorak’ by virtue of his job rather than his expensive overcoat, could keep quiet in an op.

Tom Furey sat on a fold-out canvas and tubular metal camp stool, which he had brought with him along with a Thermos of tea, sleeping bag, sandwiches, The Times crossword and a paperback novel. He pointed to the last item he’d brought. ‘What do you think that empty peanut jar in the corner is for? Or did you think there’d be a chemical toilet in here?’ Tom shook his head, but kept his gaze focused on the front door of number fourteen.

‘None of this is what I expected,’ Harry said. ‘It’s hardly like on the telly, is it? No electronic monitoring, no bank of TV sets, no infra-red night vision surveillance camera. Certainly no bleedin’ chemical toilet. Just a naff old van lined with bloody foam and plywood and a peephole. God save us if this is the front line of the high-tech war on terrorism. And I still need to piss.’

‘I got a bladder infection from sharing my piss jar with a bloke during a surveillance op in ’92, watching an IRA safe house in Kilburn, and I’m not going to make that mistake again. Like pissing razorblades, it was.’

‘Oh dear … the IRA. Tell us what else you did in the war, Dad.’

The members of the old Metropolitan Police Special Branch – also known as SO12 – had a wide array of skills which were in demand in the new fight against terrorism, and the reason they were sitting in the van was because the word was that the targets inside number fourteen – Pakistani gentlemen – had possible links to al-Qaeda. As well as prostitutes and illegal workers, their clients were believed to include a bomb maker or two.

Tom had joined the Met twenty-one years earlier, at the age of twenty-two. After his sixteen-week training course at Hendon he’d graduated as a police constable and served his probation in Brixton. Three years later, with the IRA’s mainland bombing campaign in full swing, he’d applied to join Special Branch. Being the first on the scene after a bomb had severed an army recruiter in two outside his shopfront had galvanised Tom into taking this next step in his career.

After passing a selection board he’d gone back to Hendon for eleven weeks of training as a detective. As a detective constable he’d done time on B Squad – the Irish squad – and on surveillance on S Squad. Working undercover, often dressed in the foul-smelling rags of a vagrant on the cold streets of London, spending time holed up in abandoned buildings and cold, darkened vans, he’d honed his observation skills and learned patience.

‘Give us the peanut jar,’ Harry said.

‘Quiet.’

After passing his sergeant’s exam Tom had reluctantly gone back into uniform – the obligation came with the promotion. He spent time in his new rank at Enfield – another reason why he was once more on the town’s streets. He knew the area better than most of the others on this hastily cobbled together operation.

Eventually he’d made his way back to Special Branch, where he believed he belonged and would see out his career. After completing firearms training he’d gone to A Squad, where he became a qualified protection officer. Like anyone else in the job he cringed at the term bodyguard, but that was how a civilian or, worse, a newspaper reporter, would have described him.

There had been innumerable wins for Special Branch against the Irish, but it was some high-profile cases of alleged heavy handedness – including one that was made into a movie – which made the politicians want to rein in the Branch and soften its image. Reorganisations after September 11 and the London bombings of 7 July 2005 had created a new unit to deal with terrorism, but had also removed the structure whereby detectives could transfer easily from squad to squad in the Branch, developing and practising new skills while staying under the same command.

The latest round of restructuring had hived off specialist protection – Tom’s specialty – into a new unit, SO1, under the Special Operations umbrella. Police counter–terrorism operations were now handled by SO15.

Tom Furey had provided protection for a plethora of politicians, a former prime minister, a couple of European monarchs, African dictators, and an Arabian prince or two. Visiting dignitaries were assigned British policemen to guard them when in the UK, and Tom, who had no ‘principal’ of his own to protect these days, was on a roster of unattached protection officers who waited their turn potentially to take a bullet for a foreign VIP. He liked the work – he met interesting people and occasionally travelled abroad – but if he was honest with himself it was no high-minded calling which kept him in this job. It was the money. With shift allowances he made two to three times what he would as a detective elsewhere in the Met. The downside was that divorces were common in his line of work. He and Alex had been able to cope because they’d spent their entire marriage out of sync when it came to working hours. They’d compensated with some wonderfully luxurious overseas holidays, made possible by their combined wages which were nothing to sneeze at.

Occasionally, when SO15 was stretched thin – such as now – Tom was called on to lend a hand with surveillance or other specialist tasks now out of the remit of a protection officer. The threat level against the UK had recently been upped, as a result of an increased troop presence in Afghanistan, and resources were stretched thin.

Harry, too, was a protection officer, though unlike under the old Special Branch structure he was neither experienced in surveillance nor a qualified detective. He’d only been out of uniform six months. It was a sign of the times.

‘Do you expect me to piss my pants, Tom?’

‘Shut it,’ Tom hissed back at Harry. He spoke softly but clearly and slowly into his radio: ‘All call signs, two targets moving. Heading left, towards the high street. Usual clothing. I have eyeball. Four-two, they’re heading your way, over.’ Tom repeated the direction of movement so there could be no confusion among the other call signs in the area – a mix of police and MI5 intelligence service personnel – about where the two young Pakistani men were heading. Four-two was the code name for an undercover policeman on a motorcycle, Detective Constable Paul Davis in this case, who was currently at the end of the suburban side street, where it met Enfield Road.

Harry was quiet now and Tom could almost smell the sudden burst of adrenaline in the dank confines of the surveillance van.

Three hundred metres away, down the end of the road, around the corner from the off-licence, was a kebab shop. It was the habit of the two targets to walk to the eatery between seven-thirty and eight pm each evening to buy their supper and sit down at the laminate-topped tables in the padded booth seating to eat. With kebabs, Cokes and tea and cigarettes to follow, the meal usually took two hours, according to the other watchers.

Tom spoke into the hand-held radio again. ‘Four-two, I’ve lost eyeball, do you have them, over?’

‘Roger. They’re on their way to dinner, over. Heading for the shop,’ Paul said.

Tom radioed the constable who had driven the van on to the plot – the location of the operation – and told him to come and pick them up. The officer, who had been watching television and drinking numerous cups of tea with an elderly couple who lived ten doors away from the target house, walked up the street. He wore blue tradesman’s overalls and carried a canvas tool bag. He climbed into the van without acknowledging the others in the back, started the engine and drove away from the high street, around a bend and out of sight of number fourteen.

‘Right, let’s go,’ Tom said, when the driver switched off the engine.

The back door of the van swung open and Tom, Steve the Anorak and Harry, who seemed to have forgotten his bursting bladder, climbed out.

‘Not too fast, now,’ Tom said. He looked up and down the street, which was deserted.

Tom wore jeans and a thick black roll-neck jumper, with a duffel coat over the top. It was cold out, a chilly November evening, but the jacket’s other purpose was to conceal his weapon. He carried a tool bag, though, like the driver’s, it was more for show than anything else. The tools of his trade for this job – his set of lock picks – were in his pocket.

Tom led them back up the street, then along a side path to the semi’s back door. Within three minutes they were inside. He didn’t need to tell the other two to be quick or quiet, but he reminded Harry, ‘You stay here and watch the back. I’ll go with our friend.’

The house smelled musty and unloved. He checked the kitchen. Tea bags and a kettle, no plates in the sink or evidence of home cooking. These boys ate out every night and their routine would be their undoing. With more people, more resources, they could have conducted a detailed search of the house, but tonight they had the Anorak, so the computer was their highest priority, and protecting the information technology expert was Tom’s.

He took up position in the front room, peering through a crack in the curtains so he could watch the front street for activity.

The computer was in the front room as well, on a cheap flat-pack desk. Apart from the machine and the second-hand office chair in which the Anorak sat, was a tatty velvet couch and a mismatched armchair.

Tom glanced back over his shoulder and saw Steve’s pimply young face bathed in a blue glow as he booted up the computer. Fingers encased in latex gloves tapped furiously at the keyboard. He heard a dog bark and the hairs stood up on the back of his neck. ‘Everything okay back there?’ he radioed Harry.

‘Dunno. Something’s spooked the dog in the yard behind us. Should I go take a look?’

‘No, stay where you are, but keep watch.’

‘Fuck,’ the Anorak said. ‘You should see this.’

‘What is it?’ Tom asked, his eyes still on the street.

‘Porn!’

Tom shook his head. ‘Bloody hell. Just get on with it, will you. You know what we’re after – emails, names, message traffic. I shouldn’t have to tell you your job.’

‘No, but, Jesus, you should see this. It’s some sick shit, man.’

Tom was about to say something when Paul Davis’s voice hissed in his ear. ‘This is Four-two. Targets are turning back. Just walked into the shop then came straight back out again. There’s an argument going on, by the look of it, and one of them is searching his jacket. Looks like he might have forgotten his wallet. Repeat, they’re heading back.’

‘Shit,’ Tom said. He looked over at Steve, who stared fixedly at the screen. Tom noticed, for the first time, the black leather billfold on the computer table.

‘Shut it down, we’re going.’

‘But this is gold!’

‘Leave the fucking porn alone and close down. They’re on their way back, so we’re moving.’

‘No way, man, we can’t leave this. I’m taking it with me. This is more than just porn.’

Tom shook his head. This was turning into a monumental fuck-up. ‘You know as well as I do we can’t nick the computer. Can’t you save whatever it is onto a disk or something?’

Steve fumbled in the pocket of his overcoat and fished out a USB jump stick.

‘Movement!’ Tom heard the word in his earpiece and drew the Glock from his holster with practised ease. He kept a spare magazine of bullets in the right-hand pocket of his jacket so that when he reached for his pistol the added weight helped swing the tail of the duffel out of the way.

‘What is it?’

‘I thought I saw a man’s head, moving along number twelve’s side fence, on the other side,’ Harry answered.

‘Keep a watch. But get ready to move. The targets are on their way back.’

‘Shit.’ Harry drew his weapon.

A dog barked and Tom’s peripheral vision registered lights being turned on in neighbouring homes. A baby screamed in the house next door, through the communal wall. It was a good reminder there were innocents all around them.

‘We’re going.’ Tom reached out and grabbed Steve by the collar of his coat, but the IT expert brushed his hand away with more strength than he’d expected. ‘Leave me alone, Furey! This is bloody important.’

‘Shit, there’s definitely someone moving on the other side of the back fence,’ Harry whispered, his voice barely audible in Tom’s earpiece. ‘I can see him through the fence palings. What should I do?’

‘Move now, out the front door. No arguments,’ Tom said to the man behind the computer, then repeated the instructions to Harry.

‘Two minutes, that’s all I need,’ the Anorak pleaded.

Tom swore. He looked out the window, down the street, and saw the two targets walking towards them, a hundred metres away.

Harry came in through the back door. ‘Lost sight of the geezer.’

‘Tell me this is worth blowing the whole operation over,’ Tom said to Steve.

Steve looked up at him, his already sun-deprived face ghostly in the wash of illumination. The man swallowed and Tom watched the overly large Adam’s apple bob. ‘Yes.’

Tom opened the front door and strode onto the pavement, raising his Glock and cross-bracing his firing hand on top of his left wrist. ‘Armed police! Get down on the ground, now!’ Harry was beside him, mimicking his stance.

The man on the right reached into the pocket of his vinyl bomber jacket and Tom started to squeeze the trigger. Before he pulled it all the way, however, the man was falling, knocked sideways by an invisible sledgehammer. There was no sound of a shot fired, so it wasn’t Harry who had downed him. Silencer.

Tom turned and registered a dark shadow moving by the corner of the house. The falling man had drawn not a gun but a set of keys from his pocket. Tom saw he held a small black plastic remote in his hand, the kind used to activate a car alarm, and presumed he pressed the button as he fell. Before he hit the ground his companion was also knocked over. Tom dropped to one knee and looked left. He registered a running man, dressed in black, a pistol in his hand. Harry shifted his aim and opened his mouth to speak.

Before either of them could order the stranger to stop, the house exploded.

2

A fireman found Steve the Anorak’s body after the blaze had been extinguished. Harry sat with his feet in the gutter, his head in his hands. There was the smell of fresh vomit near him.

Tom sat on the bonnet of a police Mondeo, his hands wrapped around a takeaway tea in a Styrofoam cup. The local residents had long since foregone their television sets – in fact, some of them were on TV now, fodder for the reporters who roamed from person to person, looking for the neighbour who could describe the conflagration in the most graphic detail. He tenderly fingered the cut above his left eye. A shard of flying glass from number fourteen’s front windows had sliced a furrow parallel to his eyebrow, but the ambulance paramedics had been able to close the wound with adhesive butterfly stitches. Despite the crusted blood down his cheek he would be okay.

‘Not much left of our computer wizard,’ Chief Inspector David Shuttleworth said, his breath clouding as he strode over. ‘Looks like the bomb was planted somewhere in the centre of the front room – perhaps even under the computer desk itself.’

‘I don’t know what was on that machine, guv, other than some porn, but he died for it.’

‘Aye, well, there’s no way we’ll know now,’ Shuttleworth said. He fished a packet of Dunhill from his Barbour jacket and offered Tom a cigarette.

Tom shook his head. ‘Given up. Again.’

‘Suit yourself.’ Shuttleworth paused to light up. ‘Cock-up hardly begins to describe this one, Tom. What do you make of the presence of the shooter, as well as the Pakistanis?’

Tom shrugged. ‘My guess is that he was watching the house, as were we, and he was sneaking in to take up an ambush position, though I have no idea why.’

‘Well, we know the two dead chaps were people smugglers, who were supposedly doing their bit for world Jihad by helping out the odd terrorist with papers and money and the like, but why would our man in black shoot them?’

‘Because they knew too much and he couldn’t risk them being caught?’ Tom sipped his tea.

Shuttleworth nodded and took a long drag on his cigarette. The smoke and frozen breath wreathed his head and shoulders in a shimmering aura, backlit by red and blue flashing lights. ‘They’re getting better at covering their tracks all the time.’

‘The IT guy was just about wetting himself over whatever was on that machine.’

‘Why did you not just take the computer or the hard drive?’

Tom looked across at his superior and frowned. They both knew the answer to that question. The United Kingdom might be at war with Islamic fundamentalist terror groups, but they still had to fight by the rule of law.

Shuttleworth checked his notebook again. ‘You say he gave no indication about what he’d found on the hard drive other than …’

‘Porn. Like I told you. “Some sick shit” was all he said, though I’m betting he didn’t stay on just to check out some fuck pictures.’

‘Well, we’ve got two dead suspects, three injured civilians from next door, no computer, no computer expert and a masked assassin on the loose. Not to mention a missing protection officer.’

Tom drained his tea and crushed the cup as the rest of Shuttleworth’s comment penetrated the ringing that lingered in his ears from the bomb blast. ‘Who’s missing?’

‘Nick.’

‘What happened?’

‘He was supposed to be at a political fundraising dinner in the city with Robert Greeves this evening, but he didn’t show. Caused a hell of a stink. He dropped Greeves at his home at five, but didn’t return to collect him at seven. We’ve tried his home and mobile phone, but there’s no answer. Deidre hasn’t heard from him either.’

Tom frowned. Nick Roberts had been a friend once – they had joined the Met at about the same age and had matching careers. Nick’s ex-wife, Deidre, had worked as a nurse in the same hospital as Tom’s wife Alexandra, and it was really the two women who had been close friends. After Nick and Deidre’s divorce, and Alex’s death, he and Nick had seen little of each other outside of work. As protection officers, both spent long periods away from home. Those absences had cost Nick his marriage but provided blessed relief for Tom, as the job had helped him a little by taking him away on a regular basis from his lonely home full of memories.

‘That’s odd. I’ve never heard of him missing a job.’

‘Any problems that you know of?’ Chief Inspector Shuttleworth, a Scot, was new to their team, having transferred in on promotion, so he still didn’t know all of his officers’ idiosyncrasies.

‘With Nick? Not that I know of. Likes a drink – who doesn’t in our job – but he’s never called in sick because of a hangover, if that’s what you mean. Seems to have a different bird every few weeks.’

Tom felt uncomfortable singing Nick’s praises any more than that. Once, when they were both on the same team protecting a visiting African head of state, a group of a dozen expatriate dissidents had staged a protest outside the London restaurant where the president was dining. Nick had warned one of the demonstrators to back off when he approached the principal too closely. The man, who appeared drunk, had told Nick to fuck off. Nick had punched the man, hard and fast in the stomach, with enough force to drop him. Someone on the team – not Tom – had reported the incident. Tom had expected the protestor to lay a formal complaint, and took the view that if he was called to make a statement he would do so, truthfully. Nick had used unnecessary force. Word got back to the squad’s former chief superintendent and Nick had been called into his office to explain his version of events. Fortunately for Nick, the complainant never came forward. There had been speculation around the office that a couple of the president’s personal staff had leaned on the witness. Tom had noticed a marked cooling in his relationship with Nick and while he never said anything to Tom’s face, Tom suspected that Nick thought it was he who had gone to their governor behind his back.

‘Deidre didn’t seem too worried when I spoke to her. I know divorce is never pretty, but it was like he could have died and she couldn’t have cared less.’

Tom shrugged. ‘I can call round his place if you like. We – I mean, I – still have a key. Alex and Deidre used to check in on each other’s places when we were on holidays. Water the plants and all. Nick stayed in the family home and Deidre bought a new place.’

Shuttleworth nodded. ‘Aye, okay. If you find him in bed with a tart or a hangover, shoot him, please, before the Minister for Defence Procurement catches up with him. It’ll be the kindest thing all round.’

Shuttleworth had suggested he see the Met’s psychiatrist in the morning for stress counselling, but Tom reckoned a lie-in might be a more therapeutic option. It was going to be a late night.

He waved his thanks to the constable who had driven him to his home in Highgate and walked up the steps to his terrace house. Southwood Lane was pretty posh these days – the habitat of bankers, lawyers, doctors and the like. Though he didn’t wear a uniform he was pretty sure most of the people up and down the street knew he was a copper. It was probably why they kept their distance. He’d grown up in the house and lived there most of his life, apart from six years in his early twenties after he’d joined the Met. Tom was an only child whose parents had him late in life and they had passed away, within a year of each other, when he was twenty-eight. He’d been seeing Alex for four years by then and it had seemed logical, in a strange way, that the passing of his folks had been the catalyst for him to ask her to marry him.

Tom fingered the faint scar above his right eyebrow. It was barely noticeable these days, but he saw it, and touched it, every morning when he shaved. His white summer uniform shirt had been drenched in blood from the cut inflicted by a drunk armed with a broken beer bottle the night he’d met Alex, nineteen years ago. She was still an intern and she was so beautiful he couldn’t help but ask her out on a date as she stitched him back together. She’d laughed and told him that as far as she knew there were rules against that sort of thing. He persisted. She relented. She was an Essex girl made good and he’d been sure they would grow old together. Her shifts and his unusual hours at home and abroad meant they had never really lived like a normal couple. They joked to friends that they only ever saw each other on birthdays – and never Christmas because they were both working. They’d both planned on retiring early, to make up for all the lost nights.

And here he was. Alone for more than a year now. Cheated of his life and his wife. He tried not to dwell on it, but everything in the house reminded him of her. How could it not? He left the hall light off as he walked through to the kitchen. Maybe by staying in the dark the memories would dim. He found the key on the hook by the little blackboard where she used to write her shopping lists. It was right where she had left it. Alex was the last person to have touched the key to Nick’s home. He stood there in the darkened kitchen and closed his eyes. He held the key in his fist and squeezed it until he felt the pain of the serrated metal edges digging into his palm. He opened his eyes and walked out again, ignoring the four or five letters sitting on the hallway floor.

Tom’s old hard top E-type Jag started first time and the V12 purred deeply, like a giant cat welcoming its owner home with a leg rub. Alex had wanted to get a new car, but Tom liked old things – old British things – and with overtime he could even afford to fill the tank once in a while. He could never see himself driving a Renault or something Japanese.

As he drove, settling into a slow lane of traffic, a vision of Alex’s wasted body, her eyes so deep in their sockets they looked bruised, popped into his head. He screwed his eyes shut for a second. A horn blasted beside him and he realised he had momentarily drifted out of his lane. He forced himself to concentrate and ignored the young black man’s abuse as the boy racer overtook him. ‘Get a grip,’ he said out loud in the car. The clock on the dashboard said nine pm. He felt like a drink.

Tom let the traffic signs lead him to the A406 and joined the rolling traffic jam for the leg that would take him around the western side of London to Kingston in the south west, which was where Nick lived, not far from Henry the Eighth’s Hampton Court palace. He became conscious of a car beside him, not accelerating or decelerating. He looked across and saw a blonde woman in a BMW Z4 convertible. Pretty, late thirties or well-preserved early forties. She wore a plain white blouse – a businesswoman, he guessed, maybe driving home from work late. She looked across and smiled at him. He smiled back, but mustn’t have done a very good job because she planted her foot and whizzed past him. Twenty years ago he might have done the same and chased her through the traffic. Now he just felt guilty as Alex smiled back at him, bravely, despite the tubes draining and filling her poisoned body. He shook his head. They – he – had just passed the one year anniversary of her death. That had been a tough, drunken night.

The drive took him past Richmond Park. Once the hunting estate of kings, it was now a Royal Park, open to all. He negotiated his way off the A307, around Kingston’s town centre, and found the quiet street where Nick lived. He’d been there with Alex enough times to remember the way. He pulled up outside the Edwardiansemi. He rapped on the door and waited. No reply. He tried again.

He turned the key and opened the door, listening for beeps. He didn’t recall there being an alarm in the house and he hoped Nick hadn’t decided to install one since his last visit nearly two years ago.

The house was only a few degrees warmer than the cool night air, so the central heating must have been off. ‘Nick?’ he called. He walked on thick white carpet down the hallway. He vaguely remembered a darker hue. Deidre had taken Nick’s kids to live with her and her boss, an orthopaedic surgeon. Tom recalled thinking that Nick had seemed more angry at her choice of partner than the fact she had left him. Both he and Alex had sensed that the marriage had been on rocky ground for several years.

What did surprise Tom, however, was the new look in the house. The antique sideboards and overstuffed chintz sofas must have been all Deidre, as Tom almost had to blink at the minimalist, virtually all-white décor of the once cluttered lounge room. White leather and chrome retro-modern lounge chairs surrounded a glass-topped coffee table. A wide-screen plasma was hung on the wall and surround-sound speakers had taken the place of Constable prints and poorly executed landscapes by some relative of Deidre’s.

The only colour in the room came from a leopard skin in the centre of the floor. It looked garishly out of place. The kitchen, too, had been transformed from faux-country timber benchtops and wood grain laminate door panels into a sleek showpiece of gleaming stainless steel and black granite. ‘Nick?’ Tom called again, louder.

He walked upstairs and passed one of the kids’ rooms, which had been converted into an office with a flat-screen monitor on top of an antique leather-topped desk, the only concession to pre-twenty-first century living Tom had seen so far. The second bedroom contained an array of new-looking gym equipment – treadmill, exercise bike and a multifunction piece of kit which looked more like a futuristic torture device than an exercise machine. Tom jogged fifteen kilometres every second day of the week, no matter the weather, and followed his run with a hundred sit-ups and sixty push-ups. He thought gyms were posy, smelly places populated by people trying to pick each other up.

The main bedroom was the reverse of the lounge. Dark blue carpet; a king-size bed with a dark grey duvet patterned with black Chinese calligraphy; black satin sheets turned down; a feature wall painted a colour Alex would have called eggplant, and deep, dark reds on the other three. Tom turned on the light and noticed the dimmer switch. He twiddled it and smiled as he looked up into the new recessed lighting. On the feature wall was an impressionistic painting which, despite its blurred lines, was clearly of a naked woman reclining with her hands between her legs. Nick, it seemed, had embraced the bachelor lifestyle with a vengeance and this passion pit was clearly his operational headquarters. The bedside chest of drawers – made of some kind of black wood – contained two boxes of condoms and some porn DVDs. The movies were hetero and hard core by the look of them, but nothing kinky. Tom slid open a full-length mirrored wardrobe which revealed, in addition to shelves of neatly folded clothes and a rack of suits, another wide-screen TV and a player for the disks. There was also a digital video camera on a tripod. ‘You dog,’ Tom said.

What was clear was that Nick was not home and nor did he appear to have been in the house for some period of time. Tom walked back downstairs to the kitchen, where the telephone was. He had noticed the blinking red light on the answering machine, but had avoided intruding further into his colleague’s private life until necessary. It was necessary now. He pushed the button.

The machine beeped and a woman’s voice said: ‘It’s me. I don’t know how you got my number, but I’ll see you. Tonight. I’m on at the club from six until two.’ The tone sounded again. There were no other messages.

She sounded young, though her voice was quite deep, the pronunciation precise, as though the tongue was learned, not native. There was an ethnic accent there – possibly black African. Tom wondered if it was a potential girlfriend. A ‘club’ could mean a number of things. Being ‘on’ could refer to anything from working a shift behind a bar to a performance of some sort. He replayed the message. The girl’s tone was slightly annoyed. Perhaps Nick had seen her and wanted to get to know her better – hence her concern at him tracking her down. Tom hoped Nick hadn’t used police resources to get a woman’s phone number, but he wouldn’t have been the first to do so.

Tom moved to the refrigerator, intending to check how much food was there and its use-by dates to try to get a better feel for when Nick was last home. Before he opened it, a business card under an I love Ibiza magnet caught his eye. He lifted the card, holding it by the edges, for it was glossy and would probably hold a fingerprint quite well. There was a picture of a blonde in skimpy lingerie and high heels holding onto a brass pole and leaning out to one side. Club Minx was written underneath. On the back, written in pen, was a name – Ebony. A stripper’s stage name, perhaps? It gelled, too, with the African accent on the machine.

Tom’s mobile phone rang and he fished it out of the pocket of his duffel coat. ‘Hello, it’s Tom.’

‘Any luck? Are you at Nick’s place?’

It was Shuttleworth. ‘No and yes. There’s no sign of him, guv. Doesn’t look like he’s been here for …’ Tom opened the fridge door and looked inside. The shelves were bare. In the door was a carton of milk with yesterday’s date as the use-by date. ‘… for quite some time. Fridge’s empty except for some stale milk. Heating’s turned off. Has he been overseas?’

‘No, but he was on leave for four days until he went back to Greeves today. The Secretary of State for Defence and junior ministers such as Greeves are being afforded close personal protection at home and abroad now because of the latest al-Qaeda threats. Nick must have gone straight to work from wherever he was spending his break. Then he vanished this evening. Any sign that he may have come home?’

Tom held up the card from the pole-dancing club and wondered. Though they’d once been friends via their wives, he owed no loyalty to Nick, other than what he might feel towards any other member of the team. Still, it didn’t do to go insinuating a detective on protection was consorting with sex workers. ‘No, but I can pop round to his local and see if anyone there’s seen or heard from him.’

‘Aye, okay. But don’t stay out on the piss until all hours. I want to see you in my office at eight-thirty tomorrow.’

‘What happened to my appointment with the shrink?’ And my lie-in, Tom thought.

‘That can wait. You seem quite sane to me.’

Tom kicked the fridge door closed and the Ibiza magnet slipped off to the floor. When he knelt to retrieve it, he saw the corner of a small piece of white card sticking out from under the fridge. He picked it up and found it was another business card. It had the name and mobile phone number of a freelance journalist on it. Tom didn’t recognise the name. He placed it on top of the fridge after writing the details in his notebook.

Club Minx was in Soho, a part of London Tom didn’t care for. He wasn’t a prude, and had been to his fair share of strip clubs – or table-dancing clubs as this one billed itself – but the congested, seedy hub depressed him.

The drunken office Johnnys in their suits and loosened ties saw only the smiles and flesh. As a bobby Tom had found teenagers who had overdosed in toilets; toms – whores – who had been beaten by their pimps or sadistic clients; kids from abusive families with nowhere to go and no other source of income than their own bodies; girls from the Far East and the former Soviet republics sold into modern-day slavery. There was nothing terribly sexy about any of that.

By the time he’d driven the Jag back to Highgate and caught the tube into the city it was nearly midnight. He’d ditched the duffel coat and slipped on a sports coat, so he looked less like a builder and more like an off-duty businessman.

Tom got off the Northern Line at Tottenham Court Road tube station. He showed his warrant card and wished he’d brought a waterproof jacket when he saw the footpath glistening in the reflected glow of streetlights. Raindrops were hitting a muddy puddle which had formed in a gutter dammed by rubbish. He walked down Oxford Street, which was still crowded with tourists and night people, coming or going to and from pubs and clubs. This part of the city was just coming to life.

Soho still clung to its reputation for sin and sleaze, but the truth was that the strip joints, brothels and sex shops were slowly but surely losing ground to bistros, restaurants, trendy bars and cafes. A new wave of businesses, largely fuelled by the pink pound, had also grown up in Old Crompton Street. What remained of Soho’s salacious past – at least, what was still visible to passers-by – was hemmed into a warren formed by Berwick, Walker and Peter streets. On Berwick he passed a shop with leather corsets and restraints in the window and ignored the urgings of a tout to come inside and see his fully nude girls.

A grey-haired man in a suit ducked out of an adult bookstore and looked guiltily both ways before darting into the passing throng of people. A group of a dozen lads in their late teens and early twenties sang the chorus of an old Rolling Stones song – badly – as they weaved down the narrow thoroughfare. A tourist couple paused in front of him, blocking the footpath, to check their London A-Z. Tom kept his impatience in check.

‘Been in a fight?’ the bouncer asked him as he descended the stairs from Peter Street.

‘Walked into a cupboard door,’ Tom said, unconsciously fingering the glass cut above his eye. He’d forgotten about it.

The bouncer looked him up and down and, deciding he wasn’t drunk, said, ‘All right. Don’t think I need to check your ID to see if you’re underage.’

The music he heard as he walked past the doorman had a beat he could feel in his chest. Slow, grinding. Music to disrobe to.

‘Ten pounds, please,’ the girl behind the reception desk said.

Tom wished he had told Shuttleworth about his informal investigation now. There was no way he’d be able to claim entrance to a strip club on his expenses if he wasn’t officially working. He didn’t want to flash his warrant cardto the girl, which would cause a panic among the club’s workers and patrons and have them all start disappearing. He’d put money on a few of the girls being illegal immigrants.

‘Ta,’ the girl said as he handed over his money. She wore a low-cut mini-dress that left little to the imagination.

A man in his fifties, heavy set and bald, stood to one side of the counter. Extra security, Tom assumed. A skinny red-headed girl in a lime green Lycra skirt the width of a hair band and a matching boob tube tottered past on black platform-sole shoes with five-inch heels, leading an overweight man in a suit by the hand. The couple walked past reception, through a door. Tom watched their progress, then glanced back at the girl behind the cash register.

‘You been here before?’

‘No.’

‘Private shows are out the back. Just talk to any of the girls – they’ll be more than happy to oblige.’

He nodded and walked into the club. The air was heavy with a cloying mist of disinfectant, cigarette smoke and perspiration, all masked by cheap perfume. A girl dressed in white stay-up stockings and matching bra and pants smiled at him as she brushed by, carrying a tray of drinks.

In the centre of the room was a square podium, joined to the black ceiling by two brass poles. There were seats for maybe twenty people around the stage, though there were only four punters there now, up close, ogling a brunette who was naked except for a brief G-string, black patent leather high heels, nipple rings, and a garter stuffed with notes. She, too, smiled at him as he took a chair opposite the other men.

The girl turned her back to Tom and knelt in front of the men. ‘Show us everything,’ one of them said, loud enough for Tom to hear over the grinding music. She shook her head and he didn’t catch what the girl said, but the man who had spoken got up and returned to his table. His comrade got up soon after and joined him, leaving just two patrons. Tom watched them, beyond the girl’s flawless back. They had shaved heads, football shirts and too much bling. If they were crims – and judging by the spider-web tattoo on his neck, at least one of them had done time – they were small-time.

The waitress in bridal white came to Tom and he ordered a Beck’s. He also paid thirty quid for some plastic money to stuff in the girl’s garter. She was on her knees, but bent backwards until her hair brushed the stage. She was looking at Tom, upside down, and he smiled back at her.

Not getting any joy from the other two men, the girl used the pole to pull herself to her feet and, after climbing and swinging as she slid down again, crawled on all fours to Tom’s side of the podium. She grinned and winked when Tom held up a bill. She turned side on to him, so he could slide the money between her garter and her bare thigh. The transaction sealed, she leaned over him, allowing her long hair to fall around his face. Her nose was half an inch from his. She moved her mouth to his ear and blew in it.

‘Hello, my name is Ivana,’ she whispered.

‘Hello, my name’s Detective Sergeant.’

The smile vanished from the girl’s face as she rocked back on her haunches. Russian, maybe, or Ukrainian, or Latvian, or Lithuanian. It didn’t matter. He’d put a hundred quid on her being an illegal immigrant. She looked over her shoulder towards the distant reception counter.

‘Don’t worry, Ivana, the management doesn’t know I’m a copper.’ The waitress deposited Tom’s beer in front of him.

She closed her legs. ‘What do you want?’

‘World peace, job satisfaction and a lasting relationship.’

She looked at him, puzzled. ‘I have nothing to say to police.’

‘Fine then, we can have a chat at the nearest nick, if you prefer. We can stop by your home and you can collect your passport. We’ll need to check your identity and residency status.’

‘I am not illegal, and I can prove it.’

Tom sipped his beer, then shrugged. ‘Says you. I can be back in half an hour with a couple of uniformed officers. That should do wonders for business.’

She looked over her shoulder again. ‘I finish dance in a few minutes. We can talk then. But I tell you now, policeman or not, no sex.’

Tom nodded. Ivana returned to the other side of the stage to try to milk a few more quid out of the football hooligans, and Tom found a table in a dark corner of the club.

Ivana finished her dance and stepped down from the stage, to a smattering of token applause from the score or so of other customers sitting at candle-lit tables. She shrugged into an abbreviated vinyl interpretation of a nurse’s uniform and walked over to Tom. The waitress returned and Ivana looked pointedly at the other girl, then back to Tom.

‘Oh, all right. What’ll it be?’

‘Double vodka and tonic.’

Tom ordered a second beer and winced when the girl told him the price. He shelled out some notes, wishing again he had done this by the book. The waitress left them.

‘If you are police, show me your identification.’

Tom pulled out his wallet and showed his warrant card.

‘Furey? It means madness?’

‘Sometimes.’

‘Why don’t you tell the owner who you are?’ she asked him.

‘Where’s Ebony tonight?’

The girl leaned back in her chair and sipped her drink. When she put it down, she said, ‘What are you, another stalker or something?’

‘Another?’

Ivana said nothing.

‘Is she working tonight?’

‘This is not official business, I think.’

Tom checked his watch. ‘Like I said, it can be, very easily.’

Ivana sighed and flicked back from her face a long, straightened strand of jet black hair. ‘She called in ill.’

‘When was her last shift?’

‘Last night. Are you going to stay here all night and spend that tipping money you bought?’

Tom looked at the laminated play money on the table. ‘You said, “another stalker”; was there a man bothering her?’

Ivana laughed, and Tom thought how pretty she really was. ‘Men bother us every single night, Mr Policeman.’

‘You know what I mean.’

‘There was a regular customer, a guy who came maybe five, six times in last two weeks – always booked private shows.’

‘What did he look like?’

Ivana finished her vodka, slurping as she sucked the dregs through her straw. She smiled sweetly but said nothing.

Tom slid over the tipping money and she palmed it off the table.

‘Glasses, red hair, freckles. Midtwenties. Short – about five-six. Looks like academician or maybe IT geek.’

Definitely not Nick then. Tom described the other detective.

‘That could be any man who comes in here,’ Ivana shrugged.

She was right, and Tom knew it. Someone would have to bring back a picture. He wanted to know more about the girl. ‘She’s black – the girl, Ebony?’

‘Now I know why they make you detective.’

‘Hah, hah. Where’s she from, the West Indies?’

‘South Africa.’

That was a bit out of the ordinary. ‘Is she an illegal immigrant?’

‘Who are you after, her or this big guy with black hair?’

‘Has she been acting differently lately?’

‘She went home early last night. I assume it was the sickness that kept her away tonight, but I was doing private show when she left, so I did not talk to her.’

‘Were any of the other girls on tonight working last night?’

Ivana looked around the club. ‘No.’

Tom thought from her studied nonchalance that she was probably lying – perhaps to protect her co-workers. He liked that about her. Honour among strippers. ‘There were no other regulars that you know about?’

Ivana shook her head and looked at her watch. ‘I am finishing work soon. You like private show?’

Tom smiled at her. ‘No, thanks. How long has Ebony been in the UK?’

‘About a year, I think.’

‘How old is she?’

‘Young – but not under-age, if that’s what you’re thinking. About nineteen, I think. Boss here is very strict on some things. No drugs, no kids.’

Tom wondered if Nick had seen Ebony, and if he had been the reason she had left work early the previous night. He didn’t want to draw attention to himself by asking the receptionist.

‘You got wife, Mr Policeman?’ Ivana asked, intruding into his thoughts.

‘No.’

‘Girlfriend?’

‘That’s none of your business.’ He drained his beer.

‘I thought not. Policemen lousy at relationships. My policeman boyfriend in Russia, he beat me, so I stab him.’

‘Bad relationship, indeed. Call me if you remember anything else.’ He gave her a card and left the club.

It was nearly two in the morning before he opened the door to his warm but empty home. His face still stung from the cuts and he thought about the explosion again, and the death of the computer guy, Steve. He stripped off and climbed into bed between cool sheets. He looked across at the picture of Alex and smiled at her. He realised it could have just as easily been him caught in the explosion.

Part of him wished it was.

‘South Africa.’

Tom wasn’t fazed as Shuttleworth said the words, neither about the destination nor the lack of notice. He’d been to the Sudan with a foreign secretary and to Morocco with a former PM, but never to southern Africa. He looked out across the Thames, towards the Palace of Westminster. The sky was a dirty grey. Some sunshine wouldn’t be bad.

‘With Nick missing, I need you to do an advance recce prior to Robert Greeves’s visit. Flight leaves this evening, BA from Heathrow to Johannesburg,’ the Scotsman said. ‘Greeves is a frequent visitor, both for business and pleasure, and on this trip he’s doing a bit of both. He’s an animal nut – loves the game parks – and he’s staying in a luxury lodge he’s used before. While he’s there he’ll be meeting with his South African counterpart, a Mr Dule, to talk about them buying some jet training aircraft from a UK defence contractor.’

‘I read something about that.’