9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

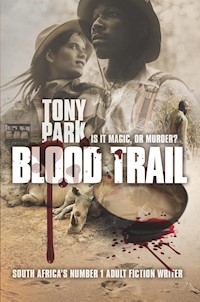

A poacher vanishes, two young girls go missing, a tourist disappears... magic or murder?

Evil is at play in a South African game reserve.

A poacher vanishes into thin air, defying logic and baffling ace tracker Mia Greenaway.

Meanwhile Captain Sannie van Rensburg, still reeling from a personal tragedy, is investigating the disappearance of two young girls who locals fear have been abducted for use in sinister traditional medicine practices.

But poachers are also employing witchcraft, paying healers for potions they believe will make them invisible and bulletproof.

When a tourist goes missing, Mia and Sannie must work together to confront their own demons and challenge everything they believe, and to follow a bloody trail that seems to vanish at every turn.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

About Blood Trail

A poacher vanishes, two young girls go missing, a tourist disappears… magic or murder?

Evil is at play in a South African game reserve.

A poacher vanishes into thin air, defying logic and baffling ace tracker Mia Greenaway.

Meanwhile Captain Sannie van Rensburg, still reeling from a personal tragedy, is investigating the disappearance of two young girls who locals fear have been abducted for use in sinister traditional medicine practices.

But poachers are also employing witchcraft, paying healers for potions they believe will make them invisible and bulletproof.

When a tourist goes missing, Mia and Sannie must work together to confront their own demons and challenge everything they believe, and to follow a bloody trail that seems to vanish at every turn.

For Nicola

Contents

Author’s note

Much of this story deals with African traditional beliefs and medicines. I have researched and consulted as widely as I can on this subject in the hope of ensuring accuracy and sensitivity.

For consistency, I have used the following spellings: umuthi or ‘the/their muthi’ (plural: imithi), a term which encompasses a range of traditional medicines, and sangoma (plural: izangoma) for a traditional healer.

The settlement of Killarney is fictitious, as are Lion Plains and Leopard Springs game reserves and the Hippo Rock Private Nature Reserve. The Sabi Sand Game Reserve and adjoining Kruger National Park are real, safe and beautiful places. I urge you to visit them as soon as you can.

Chapter 1

South Africa, in the time of COVID-19

A lion roared outside. The deep, longing call came from the pit of its belly, and made the glass pane of her bedroom window vibrate. Normally, she loved that sound, and, being that close, she might once have found it a bit scary.

Now, Captain Sannie van Rensburg felt nothing, just empty.

As she did up the buttons of her blue uniform shirt, she felt detached, as if she was dressing one of her three children, not that she’d done that for many years. Her youngest, Tommy, her laat lammetjie, was turning thirteen in a month and it wouldn’t be too many years before her late lamb didn’t need her at all. Normally she would wear plain clothes to work, but her washing basket was overflowing.

Sannie started to cry and didn’t bother even trying to wipe away the tears as she buckled her belt and adjusted the holster holding her Z88 pistol on her hip.

She went through to the kitchen. The house was still chilly in the morning, although this winter, which had seemed like it would never end, was slowly, begrudgingly, giving way to the warmer weather, which would bring rain and fresh growth. She put the empty bottle of Nederburg sauvignon blanc from the night before in the bin and rinsed her glass; she did not need more rolled eyeballs from her two sons.

The lion called again, searching for his brother or warning others to stay away. Increasingly, lions were crossing the Sabie River from the Kruger National Park into the adjoining Hippo Rock Private Nature Reserve, a housing development in the bush, where Sannie lived. Many of the houses in Hippo Rock were holiday homes and with their occupants stuck in Gauteng or the Cape or, for the foreign owners, overseas, because of travel bans, the estate had been far quieter than normal during the pandemic. The animals were, literally, taking over.

There was never a good time for a pandemic, Sannie mused as she made herself a cup of rooibos tea and a single slice of toast, hoping it would settle her stomach. The wine had been flowing last night, when she’d been at the home of her friend, Samantha Karandis. Even though sales and transport of alcohol had been banned during South Africa’s draconian lockdown, Samantha had not been miserly and the three of them – Samantha, Sannie and their friend Elizabeth Oosthuizen – had come close to finishing six bottles between them, including the half bottle Sannie had taken home and finished herself, alone.

‘I’ve got a well-stocked cellar, darling,’ Samantha had said, more than once, but Sannie, an experienced police detective, had also noticed the briefest look that passed between the two other women. If Samantha had a secret source of booze then she was surely not the only one in South Africa. Sannie had bigger crimes to worry about.

‘Mom?’ Tommy said behind her, breaking into her thoughts.

She didn’t look over her shoulder. ‘Yes, my boy?’

‘At least turn the light on.’

‘It’s not even six am, go back to bed.’ He might talk to her like a surly teenager, but she still thought of him as her little boy.

‘Lion woke me.’ He went past her to the fridge, took out the milk and swigged it from the bottle.

Normally she would have told him not to be so rude, but there was no normal any more. He was getting taller by the day, looking more and more like his father, and the resemblance would only grow as he filled out. Nature was conspiring to prolong her grief forever. She looked out the window, not wanting him to see her tears, but not caring if he did.

‘Christo will help with your homeschooling today. Do as he says, hey?’

A couple of sullen seconds’ silence. ‘All right, Mom.’

Her middle child, six years older than Tommy, happened to be at home with them. Christo was studying zoology and botany at Wits University and had been doing a practical with the Kruger Park’s veterinarians when the government announced the country was shutting down because of the virus. As the veterinarians’ work was an essential service, Christo was able to stay in the park, or move to and from their house in Hippo Rock at will. He had slept at home last night.

Sannie’s eldest, Ilana, was studying medicine at Stellenbosch University and had decided to stay in the Cape for the lockdown. Inter-provincial travel had recently reopened, throwing a slender thread rather than a lifeline to the tourism operators, but Ilana was prepping for exams.

They’d had a fight last night, Sannie and Tommy, over him spending too much time on the computer. She’d never said so to his face, nor to her husband, Tom senior, but she thought the boy was too English, spoiled by his British father who’d had no other children of his own before meeting Sannie. Ilana and Christo were by her first husband, an Afrikaans detective, like her. She felt guilty, now, that she had ever questioned Tom’s loving parenting, even silently.

‘Are you crying?’

She looked at the kitchen window and saw now that he had been watching her reflection. She wiped her eyes for the first time.

He put a hand on her shoulder. ‘I miss him too, Mom.’

Sannie covered Tommy’s hand and gave it a squeeze. ‘I know you do, my boy.’

He forced a smile. ‘I just saw on Facebook that there’s a leopard with a kill at the golf club.’

‘Animals are taking over the place,’ she said.

‘Please will you try to get a picture for me on your way to work, Mom?’

‘Sure.’

Sannie’s latest posting in the South African Police Service was as the head of the Stock Theft and Endangered Species unit, which was based at the MAJOC – the Mission Area Joint Operation Centre – the headquarters for anti-poaching in Kruger, alongside Skukuza Airport. Sannie and her small force of STES detectives were responsible for crime scene investigation and prosecutions arising from rhino and other poaching incidents. From Hippo Rock it was a fifteen-kilometre drive to the MAJOC, through the Paul Kruger entry gate across the river. She liked to get an early start on the day, especially as work was one of the few places where she could busy herself enough to not think too much about Tom. Her daily short cut through the Skukuza staff village took her past the golf club, so she could easily divert there to look quickly for Tommy’s leopard.

The Skukuza golf course, which was open to big game all the time, was being overrun by elephants and other herbivores feasting on the greens now that no one was playing. The predators, too, were arriving in numbers.

Despite a lull in rhino poaching at the start of the lockdowns, crime had been returning with the progressive reopening of the country. Poverty was a perennial problem in the communities that bordered Kruger, but with the collapse of the tourism industry due to worldwide shutdowns, many more people than usual were unemployed, adding to the police’s problems.

Sannie kissed Tommy. ‘Say goodbye to your brother for me and tell him I love him.’

‘Will do, Mom.’

Tommy opened the laptop sitting on the kitchen counter.

She held up a finger to him. ‘And do your schoolwork today. No computer games.’

He turned the laptop around to show her the screen, tapping the volume key as he did so. ‘No games, Mom. The Stayhome Safari morning drive’s just started.’

A young white woman with short, dark hair swivelled in the seat of her open-topped Land Rover game viewer and smiled at the camera while an older African man sat on the tracker’s seat attached to the front left-hand fender, watching the bush and the reddening sky. ‘Good morning from sunny, cool South Africa, and welcome to Stayhome Safari, wherever you’re logging on from in the world. I’m your ranger and field guide, Mia Greenaway, coming to you from Lion Plains Private Game Reserve, inside the world-famous Sabi Sand Game Reserve, and behind me is my very talented and knowledgeable tracker, Bongani Ngobeni. Behind the camera today is our Jill-of-all-trades Sara Skjold, all the way from Norway, though stuck here in South Africa these days. Now, let’s go find some lions!’

Sannie shook her head and manufactured a smile for Tommy. ‘Shame, you live in a nature reserve with lions calling and you have to go online to watch them.’

He grinned, and he looked so much like his father that she had to wipe her eyes again.

‘Mom?’

She picked up her car keys out of the carved wooden bowl on the bench top. ‘Yes?’

‘It’s OK to cry.’

She drew a breath and ruffled his hair. It wasn’t like she was the only one who had experienced loss during the pandemic. People had died; Samantha’s husband John had committed suicide because his tourism business had collapsed due to coronavirus, and Elizabeth’s husband Piet had left her for his secretary and escaped with the woman to Dubai, unable to face the prospect of not seeing his mistress during lockdown. ‘I know.’

As soon as she opened the front door the chill hit her hard. The lion was quiet now, but she knew he – and probably the rest of his pride – was close. She didn’t care. She went to her Toyota Fortuner, clicked the alarm remote, got in and started the engine.

As she drove off, she realised she hadn’t even bothered to check for the lion. Ordinarily, she would have had her powerful torch, scouring the surrounds for danger first.

Sannie didn’t care any more.

*

Mia had parked her Land Rover by Crocodile Pan, but the big reptile of the same name who normally resided here seemed to have taken a leave of absence. It was 6.30 am and while the early bird had the best chance of catching Africa’s big cats on the move, it had been a quiet game drive so far. The online audience, Mia had learned during lockdown, could be as demanding as the rudest rich real-time guest when it came to the Big Five.

Mia took out her binoculars and began scanning. ‘We’ll just sit here a few moments and see who might come down to drink,’ she told her worldwide audience of several thousand armchair safari experts. ‘Look at that beautiful sunrise.’

While Sara – the statuesque volunteer who did indeed seem to be able to turn her hand to anything around the game reserve – panned the camera and focused on the dawn, Mia checked the Stayhome Safari Twitter feed for questions.

@Atlanta_Alice where are lions?

@UKJim how about a leopard?

@Jozi_Babe maybe one of the hot guy safari guides would be able to find some animals? Just sayin’.

Mia smacked the phone down on the front passenger seat. Bongani languidly lifted a hand and pointed to a tamboti tree. Mia had already spotted the tiny riot of colour.

‘Sara …’

But Sara’s eyes, too, were accustomed to the telltale signs of movement and she was already swinging the camera around to track the tiny bird.

‘Oh my,’ Mia said, not needing to manufacture any excitement for the online crowd, ‘that’s one of the most beautiful birds in the bush, and one of my favourites, the pygmy kingfisher.’

Mia took a couple of seconds to focus her binoculars and marvel at how such a staggering palette could be present in a bird that would have fitted nicely into the palm of her hand. ‘Although this is a kingfisher, the pygmy actually doesn’t feed on fish. They eat insects and small reptiles, such as lizards.’

Mia flipped over her phone and looked at the feed.

@Bwana_joe it’s just a bird.

@Big_Frikkie it’s a malachite kingfisher. She needs to check her bird book.

Mia closed her eyes, then picked up her binoculars again and started to focus on the bird once more. Why am I doubting myself over some jerk sitting at home big-noting himself online?

Mia knew the answer to her own question and it rankled her.

‘Mia?’

She turned and saw Sara running her finger across her neck. ‘They’ve cut the feed. They’ve found some lions in the Timbavati.’

Mia put down her binoculars. Stayhome Safari was also webcast from an additional three reserves around South Africa. The production director, mindful of the attention span of many of their viewers, would always choose a big cat over a bird.

Bongani looked up from his phone, which he had taken out of his pocket. ‘The bird was a pygmy kingfisher. You were correct. Why did you just check with your binoculars?’

She felt her cheeks burn with a mix of embarrassment and anger. Her best friend in the world knew her too well. Bongani was right; she had doubted herself. It was like a cancer, eating away at her.

Mia spoke into her radio to the Stayhome Safari producer, Janine, who was based at a lodge in the Timbavati Game Reserve, about a hundred and twenty kilometres north of where Mia was. ‘Lion Plains closing down for a break, over.’

‘Roger, you may as well,’ Janine said.

‘That guy on Twitter’s a jerk,’ Sara said.

‘Whatever,’ Mia said. ‘Frikkie’ was, given his name, most likely a South African, like her. She and every other safari guide in the country knew that locals were often the hardest to deal with on game drives. Many of them had experience in the bush and knew their birds and animals, and all of them thought they did.

Sara took a Thermos flask out of her Fjällräven daypack. ‘Want some?’

‘Sure,’ Mia said.

‘Bongani?’ Sara asked.

‘Not for me, thank you.’ He yawned and stretched, face turned up to the morning sun, eyes closed.

Mia checked her Instagram, making the most of the phone signal, which came and went in this part of the reserve. There were large tracts of Lion Plains where there was no coverage, particularly in the areas closest to the perimeter fence. This corner of the Sabi Sand butted up against the community of Killarney and her boss, Lion Plains’ wealthy owner, the British business tycoon Julianne Clyde-Smith, had deliberately avoided paying to have mobile phone coverage extended across her property – rhino poachers used their phones to tip one another off about targets and anti-poaching patrols.

Sara leaned over from the back of the Land Rover, around her camera, and passed Mia a steaming cup. ‘Nothing tastes better than coffee out in the field. I remember one time in Afghanistan –’

‘Are you going to tell us another war story?’ Bongani interrupted.

Sara laughed.

Their banter was good-natured, and it went some way to lifting Mia’s spirits. A few other trolls were baiting her on the Twitter feed now, about not spotting any lions this morning, and Mia regretted opening the morning’s drive with a promise to her audience that she would try to find them. That was not her, and not the way she would normally conduct a drive for in-the-flesh guests. She was out of sorts.

Sara gave her a big smile. The tall blonde was wearing her old Norwegian Army desert-pattern camouflage shirt which she had worn in Afghanistan, where she had served prior to leaving the forces and embarking on her bid to see as much of the world as she could. Her adventure had started and ended in South Africa, where she had become trapped due to COVID-19.

Sara sipped her coffee. ‘When will you get to make another attempt at the master tracker’s qualification?’

Mia had been trying to focus on some of the positive comments on Twitter and Instagram and just like that, with an innocent, kindly meant question, Sara had brought her back to the one thing she didn’t want to think about.

‘Not sure,’ she said, trying to sound light. ‘COVID’s affecting everything, including assessments. I’m not sure I’m ready, anyway.’

‘You have been ready for that assessment for at least two years,’ Bongani said, without bothering to open his eyes.

‘Easy for you to say,’ Mia shot back. ‘You didn’t fail your exam.’

Bongani said nothing. Mia picked up her phone again and opened Twitter.

@rajiv_mumbai that bird was beautiful, like you, Mia.

‘Fuck.’ Mia threw her phone down on the passenger seat. When she looked up and, as she habitually did, around her, she spotted the twitch of an oversized grey ear.

‘What are you upset –’ Sara began, but Mia held up her hand to silence her and pointed at the slow-moving bulk of a white rhinoceros coming into sight. Sara shifted to get a better view, and in the process she knocked over her flask, which fell onto the metal floor of the Land Rover with a loud clang.

The rhino, which had seemed so ponderous, spun around ninety degrees to confront the noise.

The sound of a gunshot split the morning’s peace.

Chapter 2

Once inside the Kruger Park, Sannie took the turn-off to Lake Panic and the Skukuza golf course. The greens were deserted when she arrived, a low mist hanging over the dam which served as the water hazard. In normal times a couple of golf buggies would have already been on the move, now that it was light enough to keep a lookout for predators and other dangerous animals, such as hippopotamus and buffalo.

A hippo honked somewhere nearby. She, too, had seen the leopard on Facebook, awake a couple of hours before Tommy, staring at her phone, scrolling through photos of her husband until they ended, abruptly.

She had not wanted to get out of bed. It was an effort most days and sometimes she just wanted to hide. On her days off the boys either forced her to get up – perhaps they could see what was going on – or, more often than not, she had to be up first to get them organised and moving.

Sannie stopped by the clubhouse and identified the tree where the leopard had hoisted its kill the previous afternoon. Sannie remembered lunches and brunches here with friends; birthday parties. It was a Kruger Park staff hangout. Tom had played golf, occasionally, with John and Piet, while Sannie drank wine in the sun with Samantha and Elizabeth. Her friends Hudson Brand and Sonja Kurtz had come sometimes, on the rare occasion when Sonja wasn’t off somewhere in the world killing people or bodyguarding.

‘Close personal protection,’ Tom would have corrected her. Sannie had done the same job, when they had met, though she never fought the public perception that they were bodyguards.

Close personal protection.

Tom had protected all sorts of people – politicians, bureaucrats, heads of state, rock stars. Everyone. Except himself.

Sannie had buried the man she loved, Tom Furey, former UK police protection officer and loving father, just three weeks earlier, and every day since, when she woke, she had cried when she remembered she was alone.

Of course, she wasn’t alone – she had her children, and her memories of Tom. Try as she might, however, the reminiscences that rolled over and over in her mind like a continuous video loop were of the fights they’d had and her guilt at letting Tom go back to Iraq. At the end of the day it always came back to one thing.

Money.

Stupid, God-cursed money was the reason Tom was dead. Like so many other people in South Africa they had struggled to make ends meet. Sannie had gone back to fulltime work in the South African Police Service after Tommy had started school, and while Tom senior had fancied himself as a farmer, they had been unable to make a profit from her family’s banana farm near Hazyview. They had lost the farm, in any case, to a land claim, and Tom had taken work overseas, as a protection officer for VIPs in Iraq.

An ISIS rocket, fired at one of the coalition’s last toehold bases in that terrible country, had indiscriminately robbed her of her second husband, as well as taking the lives of three soldiers, including a woman in her twenties.

Sannie reached to her side and closed her fingers around the grip of her Z88. She drew it out, aware of the whisper of steel against leather. She sat the handgun in her lap and glanced down at it.

She had only ever loved two men, and now they were both gone.

Sannie glanced in the rear-view mirror, saw the dyed blonde hair, the crow’s feet at the corners of her eyes. She was too tired and it was too early for makeup. And who would she be trying to impress anyway?

Ilana was a young woman now, pretty and brilliant, strident in her views and independence. She would be fine. Christo was strong-jawed and handsome, fair like his father, in looks and temperament. Tommy was smart, dark, brooding, perhaps a writer-cum-safari guide. A thinker. They were all good kids. The older two had never thought of Tommy as anything other than their blood, and all of them had been exposed to their share of trauma and tears.

‘Tom …’ she croaked. ‘Why?’

She knew exactly why. Because of her.

Deep inside her she knew that Tom had not just gone to Iraq because of the money, but because he was unhappy. She had been part of his problem, because she’d returned to duty in the police force. Tom was a good guy, but he was a man, with an ego, and she had sensed for some time, despite his words to the contrary, that it irked him that she was back in the police service, working, earning money.

He’d gone back to Iraq because of her. She could have tried harder to stop him, to help him find different work, but the truth, as much as she hated to admit it, was that she was relieved when he went. It was what he wanted, and the fights had stopped. But now, in addition to her grief and depression, she felt a crushing guilt.

Sannie looked at the weapon. It was old, but loved and well cared for. It had never let her down.

It was a cliché, she thought, wasn’t it? The cop who put the gun in their mouth and pulled the trigger. Men did that, like the gambler she had seen in the public toilet stall in Riverside Mall. He’d lost too big at the Emnotweni Casino, and then calmly wandered next door to the shopping mall where the poor cleaners and some supermarket worker on his break had had to deal with the aftermath.

Women used pills. Was that about vanity? It was not about certainty.

No, she would use a pistol, if her time ever came, like John Karandis had. And because she was the only cop Samantha knew, her friend had called her first. She hadn’t been part of the investigation, but it was clear John had set out to do the job properly.

Sannie’s heart felt like it would never mend. She did not want to go through the pain of losing someone again, and anyway she couldn’t imagine ever meeting anyone new. The thought was almost too much to bear.

Sannie looked at her pistol.

Samantha had a son from a previous marriage, but he lived overseas somewhere, like many of her friends’ older children. Elizabeth was Piet’s second wife and they had never had children. Samantha seemed to have come through her grief – Sannie envied her – and Elizabeth told them both that she was well rid of Piet.

‘A handsome younger helicopter pilot is a good remedy for a broken heart,’ Samantha had said last night, looking pointedly at Elizabeth, but when Sannie had gently pressed for more information, Liz had said she could neither confirm nor deny such rumours – just now, at least.

Thinking about Tommy, Sannie told herself that kids were resilient. Tommy’s hurt would heal with time.

Her phone rang, jolting her out of her dark thoughts, even more so when she saw it was Tommy.

‘Hello, my angel.’ She coughed to clear her voice as she holstered her pistol. ‘Are you all right?’

‘Mom, Mom, someone’s shooting.’

‘Where? At the house? I’m coming –’

‘No, Mom, on Stayhome Safari, now, check. Have a look at your phone, Mom, Mia’s chasing a rhino poacher right now. It’s hectic!’

‘Mia?’

‘One of the guides. Hurry. Sheesh, you might even be able to catch the poacher, or help them. Someone fired a gun at them, Mom!’

‘OK, I’ll call you back.’

Sannie wiped her eyes. This was a first, she thought, even for South Africa – a live-streaming poaching incident. She went to Facebook and found the Stayhome Safari page. Fortunately, the signal was good at the golf course and in a few seconds the live stream loaded. She saw a shaky view of a Land Rover bonnet crashing through the bush.

‘We can see him, one adult male, over,’ the young woman driving was saying into her radio as she spun the steering wheel, one-handed, then quickly used the same hand to change gears. Sannie caught a glimpse of a figure darting through the trees as the camera operator managed to focus.

Sannie’s phone rang, just then. She tore her eyes away from the feed.

‘Van Rensburg.’

‘Howzit, Sannie? Henk here.’

STES fell under the South African Police Service’s Organised Crime Division and Captain Henk de Beer was the organised crime liaison officer at the provincial capital, Mbombela, still referred to by many by its old name, Nelspruit. ‘Fine, Henk. Are you watching this stuff on Facebook, the live safari thing?’

‘What? No. What are you talking about?’

‘Lion Plains lodge in the Sabi Sand do a live-to-air game drive twice a day. My son’s addicted to it. One of the guides is chasing a poacher right now, live.’

‘Serious? That’ll be good for their ratings.’

‘I’ll call Sabi Sand security, get an update,’ she said.

‘Sure. I was just calling to tell you the boss has asked if you can go to Killarney for us this morning.’

‘What’s happening there?’

‘Missing girl.’

‘What’s that got to do with STES?’ Sannie asked.

‘It’s become political. The local community is threatening to protest, like in America. They’re saying poor people’s lives don’t matter. The grandmother of the missing girl says she’ll only talk to a senior female officer. The boss thinks you’re the closest and best person for this one, Sannie, and this time I happen to think she’s right.’

‘How old is the missing girl?’ Sannie asked. The crime was serious and would make a change from viewing yet another dead rhino carcass.

‘Thirteen. The boss asks if you can please go there now, try to talk to the girl’s family, maybe defuse things before the people gather this morning?’

Thirteen. Same age as Tommy. ‘OK, I’m heading there now.’

‘And keep me up to date on this rhino poacher thing if you hear anything more. I’ll call Sabi Sand security – you drive.’

‘Will do; Killarney’s close to the gate so I can head into the Sabi Sand afterwards.’ She started the engine. Sannie knew that with the police stretched so thin during the pandemic there was no way she or any other police could get to Lion Plains quicker than the reserve’s private anti-poaching operators. She set her phone on the dashboard so she could keep an eye on the online hunt to find the rhino poacher while she did a U-turn in order to head back out of the park to Killarney.

‘Jissus,’ she said out loud as she drove, ‘only in Africa.’

*

The Land Rover bucked like a bronco as Mia drove over a fallen tree trunk. Bongani lurched to one side and for a second looked in danger of falling off. Sara clung to her camera mount.

‘Mia, Mia, this is Sean Bourke, over.’

Mia keyed the handset. ‘Go, Sean.’

‘Mia, we’re looking for a breach in the perimeter fence now, over.’

‘Stand by, Sean.’ Mia glanced over her shoulder. ‘Kill the audio.’

‘No, no, no!’ the producer Janine shrieked in her earpiece. ‘This is going viral. We’re getting thousands of people tuning in, Mia!’

‘The bloody poachers will be watching as well and we’re not going to give them any information they don’t have,’ Mia told the producer. ‘Go to channel four, Sean.’

‘Roger, Mia.’

They both switched to the other channel, which was reserved for private talks.

‘My dog team is following up,’ Sean continued, ‘I’ve been told Captain Sannie van Rensburg, a senior cop from Kruger, is on her way to Killarney now. Looks like that’s the direction where the poacher has come from.’

Mia’s phone vibrated on silent in her pocket. ‘Wait one, please, Sean. I’ve got Vulture messaging me.’

On the screen was a WhatsApp message from Graham Foster, one of Sean’s anti-poaching rangers, who was sitting in an unmarked air-conditioned portacabin hidden away in a small clearing in the bush and surrounded by its own electric fence a hundred metres from Lion Plains’ luxury lodge, Kaya Nghala, which meant ‘home of the lion’. The Vulture system, named for the bird’s incredible eyesight, was an array of sophisticated long-range cameras – which used infrared and laser designators to see at night – trail cameras, radar, and motion-sensitive alarms and cameras positioned along Lion Plains’ section of the Sabi Sand Game Reserve perimeter fence. This impressive and expensive collection of monitoring devices was controlled via a bank of computers and four large screens in the cabin where Graham had been sitting since he crawled out of Mia’s bed at midnight, doing his best not to wake her, when he went on shift.

‘I’m getting the messages as well,’ Sean said.

Mia put down the radio handset and dialled Graham on WhatsApp as she continued to drive, using Bongani’s hand signals to navigate by.

‘Mia, hi,’ Graham said as soon as he answered. There was no time for small talk. ‘We’ve got movement. I’m trying to raise Sean on the radio, but he’s not copying.’

‘He’s in the north of the reserve checking for breaches in the fence. Sean’s getting your WhatsApps and I’ve got radio comms with him, so I can relay. Is our target on the move?’

‘I think so, yes.’

‘You think?’

‘I just spotted him, moving two hundred metres northwest of your position – I can see you both on the radar and camera, towards the perimeter fence, but it looks like he doesn’t have his rifle any more.’

Mia stopped the Land Rover and turned off the engine. Bongani looked over his shoulder and gave her a questioning look. To her tracker partner she said: ‘He’s on his way to the fence, not far from us.’

Mia put the phone back to her ear. ‘Maybe he cached the rifle, doesn’t want to get caught with it.’ That way, Mia thought, the man would claim he was simply setting or checking snares and get off with a small fine and a slap on the wrist.

‘We should follow him on foot,’ Bongani said. ‘The bush is so thick here we’ll be faster than in the Land Rover, and he won’t hear us coming and hide. If he is unarmed, he is not a problem.’

Mia glanced back at Sara, sitting behind them but leaning forward, straining to hear what was being said on the radio.

‘She will be fine. I will look after her,’ Bongani said.

Mia raised her eyebrows. ‘You?’

He smiled. ‘You will be tracking. I’ll watch over you, and Sara will be behind me, safe and sound. It will be good practice for your assessment.’

Mia wasn’t sure. ‘Graham’s got a visual on him. We can relay the message to Sean and he can send some guys, or call the police, to intercept this guy wherever he tries to get over or under the fence.’

Bongani held his tongue, but Mia could see the hunter in him was itching to go after this man. Bongani had grown up in the bush when there was still enough wild space and game for him and his siblings to track and catch small animals and birds to supplement the family diet, the way his people had always lived. If his circumstances had been different, he might very well have been a poacher, but as someone whose living depended on wildlife in a different way, he was more than ready to track down this intruder.

‘Stand by, Graham,’ she said into her phone.

‘OK, babes.’

She frowned at Bongani’s grin and called Sean on the radio.

‘Go, Mia,’ Sean said.

‘Graham picked up the poacher on the Vulture system. He gave me a rough direction in which the guy is heading.’

‘I’ll send a patrol down the fence line. We’ll catch him on his way out.’

‘Roger, Sean.’ She took a deep breath. ‘We’re going to track him on foot.’

There was a pause. Sean eventually keyed his microphone. ‘This isn’t your responsibility, Mia.’

‘Graham says the guy’s ditched his rifle. We’ll follow him, keep him in sight, but we won’t engage.’

‘Copy,’ Sean said. ‘Just be careful.’

‘Come,’ Bongani said, impatient. ‘Let’s see if we can pick up some tracks.’

Mia was undecided. This was not a good idea, particularly with a volunteer in tow, but a poacher was on the move and Mia hated the idea that a rhino might die because she did nothing, or was afraid to go after an armed man. She lifted her rifle from its cradle on the dashboard, unzipped the green canvas padded carry case and drew it out.

‘Yes!’ Sara said.

As Sara took off her headset Mia could hear their Stayhome Safari producer, Janine, yelling into the earpiece, demanding an update.

‘Switch off the camera and leave it,’ Mia said. Sara nodded and complied.

Bongani slid off his tracker seat, stowed his poncho, and then took a panga, a wickedly sharp machete, from where he kept it wedged behind the vehicle’s plastic radiator grille. The blade was in case they came across low-hanging thorny branches when tracking big game off-road or small trees that had been pushed across roads by elephants.

‘I wish I had a rifle,’ Sara said.

‘I wouldn’t let you bring it if you did,’ Mia said. ‘You’re a volunteer, not an anti-poaching ranger. If you shot someone you’d end up in prison.’

Sara looked miffed, but she was raring to go.

Mia worked the bolt on the .375-calibre hunting rifle, took five rounds from the hand-tooled cartridge belt around her waist and loaded the weapon. She rammed the bolt home, then passed the weapon to Bongani. He gave her the panga.

As they set off, she wondered what had happened to the poacher’s rifle.

Chapter 3

Jeff Beaton sat opposite the two men in camouflage fatigues in the room that served as the kitchen and meal room for the anti-poaching rangers at Lion Plains Game Reserve.

The place had the feel of a military camp, the vibe enhanced by the webbing gear and LM5 semi-automatic assault rifles waiting expectantly beside the dining table and the radio in the corner that occasionally hissed to life with updates about a poacher being pursued.

Jeff guessed the younger of the two men he was interviewing, Graham Foster, was close to his own age, twenty-six. Foster checked his chunky watch.

‘I won’t take too much of your time, I promise,’ Jeff said as he opened his laptop. ‘I imagine you’re keen to join in the pursuit of the poacher.’

‘We’re on standby,’ Foster said, ‘so, like, sorry, bru, if we have to split. You’re American?’

‘Canadian. A common mistake.’

‘Sorry, no offence.’ Foster held up his hands.

‘None taken. Happens all the time.’

Jeff typed Graham Foster’s name into the survey form on his screen. ‘And Oscar …’

‘Mdluli,’ the older man said. He looked to be in his early thirties.

Jeff entered the details. ‘Thanks for your time, guys. As you’ve probably been briefed, my studies focus on the use of imithi – you know, traditional medicine – by poachers, and –’

‘Primitive bullshit.’ Foster took a toothpick from the container on the table, leaned back in his chair and started picking his teeth.

Oscar folded his arms. Jeff looked at him and raised his eyebrows. ‘Oscar?’

‘Yes?’

‘What do you think?’

‘About what?’ He glanced sideways at his younger white partner, who looked up at the ceiling.

Jeff consulted the survey form he had prepared. ‘In the course of your duties, when you have apprehended or otherwise encountered a poacher, how often, if ever, have you encountered evidence of the poacher using umuthi?’

‘Otherwise encountered?’ Oscar asked.

‘Slotted,’ Foster weighed in.

‘Slotted?’ Jeff asked.

‘Killed, right? That’s what you mean by “otherwise encountered”, as in the ones that get shot, as opposed to the ones we catch.’

Jeff shrugged. ‘It’s open to interpretation.’

‘Like your study. Look, man, no offence, again, but this stuff is nonsense, hocus-pocus. Izangoma, the traditional healers, sell the poachers magic charms to make them invisible, to turn our bullets to water, to make the magistrates and the judges in the courts fall asleep, or the prosecutors lose their evidence. These people are preying on the poachers’ ignorance and stupidity.’

Jeff looked to Oscar again, who shrugged.

‘Oscar, how often have you encountered –’

‘All the time,’ Oscar said.

‘Umuthi?’ Jeff asked, starting to make notes.

Oscar spoke evenly, quietly: ‘This is our culture, our beliefs, the way we are, that we are talking about,’ he looked to his partner briefly, ‘not people selling something to gullible people.’

‘Kak, man.’ Foster looked to Jeff. ‘Translation: bullshit.’

Oscar turned to Graham. ‘You go to church every Sunday that you are not on duty, and you have a Bible, yes?’

‘Of course, man. I’m a Christian, like you say you are.’

‘I am a Christian. You came to my son’s baptism.’

Foster nodded. ‘I did. So, don’t tell me you believe in this rubbish.’

Oscar looked to Jeff again. ‘Faith is invisible, yes?’

‘Absolutely,’ Jeff said.

‘We believe certain things, in religion, to be absolute,’ Oscar went on, ‘even if we cannot scientifically prove them.’

Foster rolled his eyes. ‘Here we go again.’

Oscar continued, ignoring his partner. ‘The poachers believe in the … the talismans they are given, the spells. That is the important thing. It gives them confidence. A confident enemy is an effective soldier.’

‘What about your beliefs?’ Jeff asked.

Oscar looked down at the table, across to Foster, then back at Jeff. ‘They are my business.’

Jeff nodded. ‘For sure, I understand and respect that,’ he made eye contact with Foster, ‘and I’m not here to judge anyone.’

‘Nor am I, bru.’ Foster reached over and grabbed Oscar’s shoulder and squeezed it. Then he threw back his head and laughed.

Oscar exhaled. ‘There are some things that cannot be explained.’

Jeff typed into his laptop. ‘Such as?’

‘We were tracking a man, a couple of weeks ago, and –’

‘Sjoe, not that one again, bru.’

‘Please,’ Jeff said to Foster, ‘I’m interested in what Oscar has to say.’

Foster held his hands up in surrender again, then leaned back in his chair and went back to picking his teeth.

‘We followed a man to a mostly dry spruit, the Manzini, near where there is a waterhole. I was tracking him, his footsteps quite clear, and then we came to a place where there was water, a little bit … and he disappeared.’

‘You lost the spoor,’ Foster said under his breath, toothpick resting on his lower lip.

Oscar glared at his partner. ‘I did not lose anything.’

Foster shrugged. ‘So the guy backtracked.’

‘He was not backtracking,’ Oscar said.

‘How do you know?’ Jeff asked.

‘Even the best, most skilled poacher who backtracks will eventually put a foot wrong, he will step so that his foot is not exactly in the first track he made. I checked. He was not walking backwards.’

‘Right,’ Foster gave an exaggerated nod, ‘he ascended to heaven, or was beamed up by aliens.’

Jeff thought about the two men’s testimony. ‘Could he have gone upward? Was there a low-hanging branch of a tree or something like that?’

‘No,’ the other two said in unison.

At least they agreed on something.

‘You said there was water there, in the dry “sprite”, is that how you say it?’

‘Close enough. Creek, to you,’ Foster said. ‘Where there is water, poachers will walk along a stream and then exit somewhere downstream or upstream to try to confuse a tracker or throw a dog off the scent. We then cast up and down the far side until we find his spoor – his tracks, as you would say.’

Jeff nodded. ‘I see. And what did you find?’

They looked at each other. ‘Nothing,’ Oscar said.

Foster spread his hands wide. ‘What can we say? Sometimes we win, sometimes we lose. The oke could have taken off his shoes, swept the sand, used a pole and pole-vaulted for all we know. It’s never easy to track in sand. Maybe we just didn’t try hard enough.’

Jeff looked to Oscar, whose mouth was crinkled into a frown. ‘What do you think, Oscar?’

Oscar looked up from the tabletop and into his eyes. ‘That man, he disappeared.’

‘You think he had help? Some medicine – some muthi?’

‘Sheesh, Oscar,’ Foster interrupted. ‘It’s bad enough these simple poachers believe this stuff, but you?’

Jeff made a mental note to interview the anti-poaching rangers individually from now on. Foster’s scepticism was intimidating Oscar, or so he thought.

‘I was confused that day, when I saw those tracks disappear,’ Oscar said.

‘Babelaas, more like it,’ his partner scoffed.

‘I was not hungover.’

‘Sorry, man,’ Foster said, then chuckled.

‘Izangoma, they give the poachers imithi not just to protect them, but also to affect us, to make us not see clearly, to confuse us.’

Jeff nodded. ‘So I’ve heard. Was there any indication you picked up, while you were following him, that he might have been using umuthi?’

Foster reached in his breast pocket and pulled out a packet of cigarettes. ‘If you don’t need me any more, I’m going outside for a smoke.’

‘Fine with me,’ Jeff said, ‘thanks for your time.’ Thanks for nothing, he meant, though to be fair, Foster was entitled to his beliefs and he was not alone in them. Many people saw the whole business of umuthi as a rip-off, a con played by izangoma against scared men who were risking their lives to hunt rhinos.

‘Do you think you were affected by the poacher’s umuthi, Oscar?’

Oscar looked to the door, perhaps to make sure Foster was out of earshot, then back at Jeff. ‘I do not know. I can track a man, but I am telling you, this man, he disappeared. We cast along the water, both sides, upstream and downstream, and there was nothing. I felt sick that night.’

‘Sick? You were ill?’

‘Yes.’ Oscar patted his stomach. ‘I was not right inside, you know? But that morning I was fine. I wondered if it was umuthi. You asked about evidence?’

‘Yes.’

‘I did see a sign, near the last track of the man we were following.’

‘What was it?’

‘Some string, like a small rope, made from bark that had been stripped from a tree and braided. It had been laid across the track.’

‘What did that mean?’

Again, Oscar looked to the door. He ran a tongue over his lips. ‘Danger.’

Jeff was confused. ‘Do you mean it was a threat?’

Oscar shrugged. ‘It was a spell.’ He straightened, sitting taller in his chair. ‘I was not afraid of this man or his magic.’

‘Of course.’ Jeff made some more notes. ‘What happened, after you lost the man?’

Foster walked back into the room, his cigarette finished, and he was carrying a green canvas satchel bag. ‘What happened was that we found a dead rhino, covered with branches. The poachers do that so the carcass can’t be seen from the air, by helicopters or by vultures.’

‘Vultures?’ Jeff said.

Foster nodded. ‘Often that’s the first notice we get of a rhino being killed – the vultures will spot the dead animal and lead us to it. Poachers hate vultures; sometimes they even poison them deliberately just to take them out of the game.’

‘The man you were tracking killed the rhino?’ Jeff asked Oscar.

Oscar nodded, a grave look on his face. ‘Yes, we picked up his tracks by the carcass. It was the same man.’

‘And he vanished.’ Foster snapped his fingers. ‘Poof, into thin air. Magic.’

Oscar looked up at him.

Foster again put his hand on Oscar’s shoulder. ‘It’s not your fault, bru. We’ve all been outsmarted by these bastards one time or another, but we’ll catch that one and we’ll drill him, hey?’

Oscar gave a small nod.

‘Do you know,’ Foster locked eyes with Jeff, ‘that there are now more gunfights per year in the greater Kruger Park – including here – than there were at the height of the old South African Defence Force’s war in Namibia?’

‘I did not know that,’ Jeff said. ‘Do you ever get scared, Graham? Do you pray for protection?’

‘God is on our side,’ Foster said, his eyes not wavering from Jeff’s. ‘Of that I have no doubt. You can write that in your laptop.’

Jeff nodded. ‘I will. Belief systems play a role in many conflicts. In some, like the fighting in the Middle East, and in extremist terrorism, they’re the root cause.’

‘You know they tried to get izangoma on side, in the Kruger Park?’ Foster said.

Jeff knew what Foster was referring to, but he wanted to hear his take on it. ‘Really?’

‘Ja. They called all these witch doctors together for an indaba, a big meeting, and urged them not to supply umuthi to poachers. It was all a PR stunt.’

‘You don’t think it did any good?’ Jeff asked.

Foster shook his head and rubbed his thumb against his forefinger and middle finger together. ‘It’s all about money. Those guys will say one thing and then charge some dumb poacher a fortune for a spell or some potion or whatever to keep him safe.’

‘I have seen pictures, videos, on Facebook,’ Oscar interjected, ‘of American soldiers in Afghanistan and Iraq taking communion before they go into battle. Isn’t that the same thing?’

‘No.’ Foster slapped the table. ‘Those men are praying that if they get killed, they will go to heaven.’

‘Not for protection?’ Jeff asked.

Foster shrugged. ‘Well, maybe.’

‘Then it’s the same thing,’ Oscar said to his partner.

‘But,’ Foster said, ‘they’re not paying for it. This is about izangoma conning people who don’t know any better.’

Oscar said nothing, but he looked to Jeff like he was seething. Jeff decided he had definitely better keep these interviews to one on one in the future. He needed to change the subject. ‘You said you had some samples to show me, of stuff you’d confiscated from poachers?’

‘Sure,’ Foster said. He went to a storeroom adjoining the mess area and came back with a cardboard filing box. He set it down on the table, took off the lid and rummaged inside. Oscar pushed his chair back from the table.

Jeff craned forward to see what was inside.

Foster started taking out some of the objects, laid them on the table and gestured to them with a sweep of his hand. ‘Check.’

Jeff could see thin brown roots, a bundle of leaves and a snuff container. There was also a small pouch, decorated with what looked like hyena hairs on the top; it was partly open with dark powder inside. There was also a length of string or wool, dyed red and knotted in places.

‘This was gathered as evidence, but the cops don’t need it any more,’ Foster said.

‘We should put this away,’ Oscar said.

Curious, Jeff picked up the length of string. He looked to Oscar. ‘Do you mind?’

Oscar shrugged. ‘It’s fine.’

‘This is a xitsungulu, right? Hunting band?’

Oscar raised his shirt to show he wore a similar thing above his hips. ‘Not just for hunting, for protection.’

Graham stared at the ceiling and exhaled.

‘Cool,’ Jeff said. ‘The Catholic church has a similar tradition, with people wearing a scapular.’

Oscar lowered his shirt. ‘We take this stuff seriously.’

‘I respect your feelings, Oscar,’ Jeff said, next examining the pouch. ‘I’d like to find out what this is made from and what its significance is.’

‘Its significance,’ Foster said, taking up a clump of dried roots, then grinding them up between his hands, ‘is kak.’

‘No!’ Oscar reached for Foster, who brushed the fragments from his hands, stood and ground them into the cement floor with the heel of his boot.

Jeff looked down at his laptop screen.

‘Don’t do that, man,’ Oscar said to Foster.

Graham stared at him, mouth half open, and started blinking.

‘Aaagh …’

Jeff looked up.

Foster was clutching his chest near his heart with two hands. His legs began shaking and he dropped to his knees, head slumped forward.

Oscar sprang to his feet, as did Jeff.

‘Is there a medic or someone here?’ Jeff asked.

Foster was rolling on the floor, groaning.

Oscar dropped to one knee beside his partner and put a hand on his chest. ‘Tell me what’s wrong!’

Jeff went to the door of the dining room. ‘Help, help!’

Foster shuddered once more, and was then still.

Jeff darted around the dining table to get to the young man, who looked to be unconscious. ‘Heart attack?’

Then Foster thrust an arm up and grabbed Oscar by the shirtfront and started laughing.

Oscar fell back, out of reach, gasping. ‘You scared me to death.’

Foster sat up. ‘Got you!’

Jeff sat on the floor of the dining room, waiting for his heart rate to settle.

Oscar, to his surprise, joined in, laughing heartily as he helped Foster to his feet and embraced him.

Jeff shook his head. These anti-poaching guys were crazy.

The radio on the table hissed. ‘Kaya Nghala, this is Sean, over.’

Graham wiped the tears of laughter from his eyes and took up the handset. ‘Sean, this is Kaya Nghala, go.’

‘Graham, I’m trying to raise your new helicopter pilot, Mike someone, over.’

Graham pressed the send button. ‘Ja, Mike de Vries. Sorry, Sean, he tells me the bird’s gone to the mechanics in Nelspruit again. Bloody thing seems to be on the ground more than it’s in the air these days.’

‘Copy, thanks, Graham.’

Jeff wondered if the helicopter was needed to chase the poacher on the loose in the reserve. Graham told Sean he would send the pilot a WhatsApp message and then he and Oscar began going through a check of their gear, readying for battle. Jeff took his cue to leave them to it.

*

Mike de Vries had his phone in a car mount in front of him, on the control panel of Julianne Clyde-Smith’s Robinson R44 helicopter. He saw the message flash onto the screen but ignored it, concentrating instead on safely landing on the neatly manicured lawn in front of a sprawling faux-Tuscan manor.

The house was set in the rolling hills on the Sabie Road between the quaint historic town of the same name and Hazyview, the rather chaotic tourist town that serviced the Sabi Sand Game Reserve, the Kruger Park and the surrounding villages and farming areas.

Even before Mike had settled into the grass he saw Elizabeth stride from the house to meet him. Mike settled the chopper and let the engine run, blades still turning above him, to cool down. That didn’t stop Elizabeth Oosthuizen.

Bent at the waist, she jogged to the R44. The doors had been removed from the helicopter to improve visibility and to allow Mike’s passengers to fire rifles at poachers or dart guns at the animals he was often called on to help capture or immobilise for other reasons.

Elizabeth stood and leaned into the cockpit as Mike undid his safety harness and lowered his mouth to meet hers. Already her hand was in his lap, feeling for him. Any thought of responding to the phone message disappeared from his brain.

As he swung towards her she grabbed the lapels of his shirt and half dragged him out as he slid down. She wore black lycra activewear – yoga pants and a singlet top punctuated with those wonderful nipples.

Mike was able to shut down the engine, but she still had to raise her voice over the dying whine. ‘Howzit, my lovely? I must be quick, I’ve got to get to Killarney to keep up the pretence of being the good Christian lady.’

‘You?’ He laughed.

She slapped his face, not hard, but with enough force to send him over the edge. He pulled her to him and kissed her hard.

‘Here,’ she said. ‘Now.’

‘What?’

‘Like I said, I must go. Come.’

‘Yes, ma’am.’

The grass was wet and she nodded to the open rear of the helicopter. He grinned. She backed away from him and shimmied her bottom onto the floor of the cargo area, boosting herself up with her tiptoes on the chopper’s skid. Once in, she kicked off her expensive Nike shoes.

Mike unzipped his shorts as he came to her and grabbed the elasticated waist of her pants. In one motion he pulled them and her G-string off.

‘I’ve been thinking about this since I woke up, even while doing pilates,’ she said, waiting for him to put on some protection.

He moved between her legs, which she then hooked over his hips, drawing him in. It was effortless. ‘I can tell.’

She clung to him as he stood on the skid, their bodies interlaced as he arched his hips, bringing them together.

‘Quickly,’ she whispered, ‘Samantha’s due here any minute.’

‘Maybe she can join us …’

She grabbed his bottom and pinched it. ‘Dirty.’

‘OW!’

Elizabeth giggled, but Mike took her breath away as he entered her again. Over her shoulder he glanced at his watch. He was also conscious of the time. Elizabeth met his every thrust, clinging to him, eager to finish. Soon – too soon – they were done.

‘I want to spend a day doing this,’ he said.

‘Me too.’ She jumped lithely down from the open door of the helicopter, with the help of his hands on her waist. They both pulled their pants up just as they heard a vehicle coming up the long driveway behind them. Samantha’s white Amarok pickup came into view.

‘The wine?’

He grinned. ‘All part of the service.’

Samantha drove up to the chopper, stopped, leaving the engine running, and got out. ‘I see I’m just in time for the express delivery.’

Mike reached into the back of the helicopter and took out a box of six bottles of sauvignon blanc.

‘Howzit, Mike,’ Samantha said. ‘You can put them both in my vehicle.’

Samantha kissed Elizabeth on the cheek, and Mike couldn’t help but think of the suggestion he’d made to Elizabeth. Both women were quite a bit older than he, but Elizabeth was crazier than any girl he’d been with. He was, however, on a tight schedule. He unloaded the second box and put them both in the back of the truck, which was already full of bulging plastic shopping bags. Samantha reached in and camouflaged the contraband wine under bags of food.

‘You’re a darl, Mike,’ Samantha said.

‘My pleasure.’

Elizabeth reached into the phone pocket of her yoga pants and took out a wad of hundred-rand notes, which she handed to Mike. ‘For services duly rendered.’

He touched his forelock. ‘My pleasure. Sorry ladies, I have to go.’

Mike climbed up into the pilot’s seat and began a quick check.

‘Are you all right, Liz?’ Samantha asked as the two of them backed away towards the bakkie. ‘Your rosy cheeks make you look like you’ve just done a hard cardio workout.’

Mike was still grinning as the engine spun up and he lifted off from the farm. There were some things happening under COVID that troubled him greatly, but it wasn’t all bad.

Chapter 4

Captain Sannie van Rensburg held the sobbing woman to her chest and let the grandmother’s tears soak her uniform shirt. It took all the strength she had left in her not to join the woman and let her own grief spill out.

Sannie wore her face mask and should not have been holding the woman, but her innate sense of compassion won out over regulations.