8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

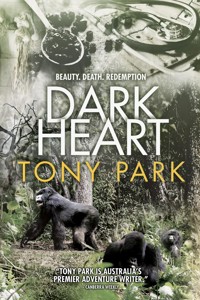

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

From the ashes of an African genocide lost love and a new evil arise.

Lawyer Mike Ioannou is dead after a hit and run in Thailand. A home invasion threatens the life of medico Richard Dunlop. In Johannesburg, a car jacker nearly kills photo journalist Liesl Nel. Unrelated incidents in a dangerous world, or something else entirely?

Australian war crimes prosecutor Carmel Shang joins the dots. All three victims are linked by a photograph that was clutched in the hand of a dying man nearly twenty years ago. The picture holds a clue to how madness gripped a country resulting in a million people losing their lives.

Carmel has to not only confront the perpetrators of the unprecedented slaughter, but Richard and Liesl, the two people she never wanted to see again. Richard was the UN military doctor she was in love with in Rwanda, and Liesl was the woman who came between them. Now they are thrown together again, desperately trying to find out why the photograph is making them the target of an assassin.

In a quest that takes them from South Africa’s Kruger National Park to Zambia, Australia, and back to Rwanda, where it all began, they find that amidst the indestructible majesty and beauty of Africa, yesterday’s merchants of death are dealing in a new currency – illegal traditional medicine and the barbaric live trade in endangered African wildlife; businesses they’re prepared to kill for to protect.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

About Dark Heart

From the ashes of an African genocide lost love and a new evil arise.

Lawyer Mike Ioannou is dead after a hit and run in Thailand. A home invasion threatens the life of medico Richard Dunlop. In Johannesburg, a car jacker nearly kills photo journalist Liesl Nel. Unrelated incidents in a dangerous world, or something else entirely?

Australian war crimes prosecutor Carmel Shang joins the dots. All three victims are linked by a photograph that was clutched in the hand of a dying man nearly twenty years ago. The picture holds a clue to how madness gripped a country resulting in a million people losing their lives.

Carmel has to not only confront the perpetrators of the unprecedented slaughter, but Richard and Liesl, the two people she never wanted to see again. Richard was the UN military doctor she was in love with in Rwanda, and Liesl was the woman who came between them. Now they are thrown together again, desperately trying to find out why the photograph is making them the target of an assassin.

In a quest that takes them from South Africa’s Kruger National Park to Zambia, Australia, and back to Rwanda, where it all began, they find that amidst the indestructible majesty and beauty of Africa, yesterday’s merchants of death are dealing in a new currency – illegal traditional medicine and the barbaric live trade in endangered African wildlife; businesses they’re prepared to kill for to protect.

For Nicola

Contents

Glossary

Akazu: literally, ‘little house’, this small circle of Hutu relatives and friends of President Juvenal Habyarimana and his wife, Agathe, were opposed to power sharing with the Tutsi, and contributed to the organisation of the Rwandan genocide.

bakkie: Afrikaans term for pickup or utility vehicle.

DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo; formerly Zaire.

FAR: Forces Armées Rwandaises; the Hutu-dominated Rwandan national army, in existence until 1994 when the Rwandan Patriotic Army and Rwandan Patriotic Front took control of the country.

gacaca: literally, ‘justice on the grass’; a community-based court system introduced to deal with the high numbers of people accused of genocide.

génocidaires: those accused of perpetrating the 1994 Rwandan genocide of Tutsis and moderate Hutus between 6 April and mid July, during which up to a million people were killed.

Habyarimana, Juvenal: Hutu president of Rwanda from 1973 until his death in 1994, when his Dassault Falcon 50 aircraft was shot down by a surface-to-air missile. Also on board and killed was the president of Burundi, Cyprien Ntaryamira.

Hutu: central African ethnic group existing in Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The majority tribe in Rwanda (with the others being the Tutsi and the Twa), the Hutu were disenfranchised under Belgian colonial rule, which favoured the Tutsi minority. After 1959, however, the balance of power changed in favour of the Hutu, until after the genocide.

Hutu Power: an extremist anti-Tutsi ideology which spawned several political parties in the lead-up to the 1994 genocide with the aim of excluding or eliminating Tutsis from Rwanda.

ICTR: International Criminal Tribunal Rwanda. UN body formed in November 1994 to investigate and prosecute those accused of genocide and other violations of human rights in Rwanda.

Interahamwe: literally, ‘those who stand together’, or fight together, this government-backed Hutu paramilitary group was responsible for carrying out the genocide against Tutsis and moderate Hutus in Rwanda.

Kibeho: Small town in southern Rwanda which prior to the genocide attained fame as the site of reported visions of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ. It was also the site of the largest post-genocide Hutu refugee camp where génocidaires and innocent Hutus fearing RPA reprisals sought shelter.

muti: common southern African term for traditional medicine made from plant matter and animal and (in some cases) human body parts.

RPA: Rwandan Patriotic Army. The armed wing of the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front. Made up of exiled Tutsis, the RPA, led by Paul Kagame, took control of Rwanda following the 1994 genocide.

RPF: Rwandan Patriot Front. Political party formed in 1987 by Tutsis living in exile from Rwanda in Uganda. The RPF took power in Rwanda in 1994, won a majority in the 2003 elections and at the time of writing (2012) the RPF was still the ruling party in Rwanda.

Tutsi: ethnic grouping in Rwanda, Burundi and Democratic Republic of Congo; the second largest grouping in Rwanda (with Hutus in the majority and Twa in the minority). Initially favoured over the Hutu by the Belgian colonial regime, the Tutsi faced reprisal killings and persecution following the 1959 transition to majority rule. Many fled the country for neighbouring Uganda. The 1994 genocide was aimed at eliminating the Tutsi in Rwanda.

UNAMIR: United Nations Assistance Mission For Rwanda. UN peacekeeping force first established in 1993, prior to the genocide, to enforce the terms of the Arusha accords which would have allowed exiled Tutsis safe return to Rwanda.

Prologue

Koh Samui, Thailand, December 2011

The girl looked back over her shoulder and winked at him, then leaned across the pool table, one short but slender leg raised, and lined up the white and the eight balls. A sunburnt Swede on the other side of the green felt, old enough to be her father, leered at her sloppily.

The balls kissed and the black slammed into the corner pocket. The Swede shook his head, laid down his cue and shook her hand. The girl looked back at Mike Ioannou and winked again.

Mike looked at his watch. It was one in the morning. He was alone and drunk. He drained his lukewarm half-litre glass of Singha beer and then groaned as the girl, who had just clinched her fifth straight game of pool, sashayed towards him with a full beer. She’d been working on him all night, in between matches.

‘Kop kuhn, I think,’ he said to her, and reluctantly took a sip. At least this one was cold. Why me? he wondered. Well, he surmised as she dragged a stool next to his, he was better looking than the Swede, who had a huge beer belly and was wearing sandals and socks and plaid shorts.

‘You look me all night. We go party now?’ she said to him, adjusting herself on her seat so that her thigh, most of which was visible thanks to her tiny denim shorts, was resting along his.

‘No, thank you,’ Ioannou said. He had been looking at her all night, but he had no desire to take home a dose of something.

She nudged him with her shoulder, making him spill a little of his beer, which annoyed him. ‘You say you from Australia, but you no look Australian. You look Italian.’

He laughed and shook his head. ‘I live in Australia now, but my family’s from Cyprus originally. You know where that is?’

‘No. Maybe you show me one day.’

‘Maybe you should go back to your pool table.’

She leaned closer to him and lowered her voice. ‘Me no want boom boom, me good girl. We just go dance, maybe play some pool somewhere else, just you and me, OK?’

Her pretence of innocence was oddly appealing. ‘You’re too good for me – at pool.’

She slapped his back. ‘I teach you. Is OK.’ She took his left hand in hers and held it up. ‘I see you married.’ The girl brought his hand to her lips and kissed it. As her lips brushed the gold band he felt her tongue linger on his skin.

‘Enough.’ He drew his hand away from her.

She looked up, smiling, and fixed on his eyes.‘You faithful. That nice.’ She lowered her voice: ‘Make me so horny.’

Mike laughed out loud and she joined in. ‘No thanks.’

She punched his arm. ‘Come on. Your friend – birthday boy – he go get his present. Now you all alone. What you do, go home to hotel and play with yourself?’

He couldn’t help but laugh. She was fun and her smile was infectious. He checked his watch again and looked around the bar. Ironically, it was called Henry’s Africa Bar. He hadn’t chosen it and hadn’t noticed the sign as he had walked in. It was only once he was inside that he’d noticed the leopard-print wallpaper and carved wooden giraffes. There was a South African flag behind the bar and a framed Springbok’s jersey. But that was about where the African ambience ended. The waitresses were all wearing cowgirl hats and garishly coloured riding boots and dispensing shots from mini bottles of vodka slung in leather bandoliers crisscrossing their tiny bodies.

Mike didn’t want to think about Africa. He’d come here to try to forget, if only for a few days. He knew that if he did go back to the hotel now, he wouldn’t surf porn on his laptop; instead, he’d start going over the transcripts again, agonising over what more he could do to find the men in the photograph, now that he’d identified them.

‘I think,’ the girl said, loudly enough to break his thoughts, ‘time we go now.’

He had a wife and two teenage daughters at home. ‘I just don’t understand you,’ his wife, Helen, had said to him a week ago. It was clichéd, corny even, when he thought about it. He could tell the girl his wife didn’t understand him and use it as justification to fuck her brains out tonight.

But he wouldn’t do that. His wife couldn’t comprehend why and how he had got himself so enmeshed in something that had happened seventeen years earlier in an African country that few people in Australia would have even heard of had its citizens not set about massacring each other on a scale not seen since the Nazi death camps.

He’d taken a job as prosecutor and investigator for the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the ICTR, to get back to Africa, and to try to do some good. He’d had enough of defending drug dealers and white-collar embezzlers.

Although his parents were Cypriot and he lived in Australia, Mike had been born in Africa, in Rhodesia, now known as Zimbabwe, where his mother and father had owned a supermarket. They had been forced to leave Africa when Robert Mugabe ruined Zimbabwe’s economy by destroying its commercial farming sector. In his adopted country Mike had stuck out more because of his funny accent than his looks. Most people thought he was South African and for a while Mike didn’t know who he was – a Cypriot, an African or an Australian. His wife was all Australian and couldn’t understand why he would want to go back to Africa, least of all to a country like Rwanda. She had gone with him once, to go to a friend’s wedding in Bulawayo, in Zimbabwe, and had hated every minute of it.

He didn’t want to lose her. He didn’t want to seek solace in the arms of a Thai girl half his age. What Mike Ioannou wanted most of all was his life – his pre-Rwanda life – back, working as a barrister in Sydney. He’d been too good at his job. And now he was opening a can of worms that maybe should have stayed closed.

The girl ran her hand up the inside of his thigh. He was wearing cargo shorts and hadn’t bothered with underpants. She grinned as she felt him harden, despite his protestations and the amount of beer he’d had. ‘No,’ he said, though he knew she could sense that his conviction was wavering.

‘Yes.’ She took his earlobe between her teeth and bit down gently. He groaned.

Mike knew that in two days he would have to confront the reality, the enormity, of what his investigations had uncovered. He rubbed a hand over his face. The girl gripped his arm and tugged.

He tried to resist her. He wanted Rwanda to be over and to go home, once and for all, to his wife and to never see Africa again. He wondered if he could. He wondered if the evil had poisoned him, changed him, so that he could never be normal, never be good again.

But why had he bothered? Did anyone in the world care any more?

‘Africa,’ he muttered.

‘What you say?’ the girl asked him. She held him at arm’s length, toying with his fingers, tugging on them as she leaned her lithe body back.

‘I said, Africa. Do you know why people would rise up against their neighbours in a godforsaken little country in the middle of nowhere and murder nearly a million people? Do you know what would make people do that?’

She tilted her head and he assumed her English wasn’t good enough for her to comprehend his words or his despair. She let go of his hand and came closer to him. She stood between his spread knees but she didn’t touch him. ‘I not Thai. I come from Cambodia.’

‘Oh.’

‘Yes. I here because I got baby, and I no got mother, no got father, no got uncle, aunt, cousin. I got only me to care my baby. I got no family. I know ’bout Rwanda. I know ’bout people killing each other, mister.’ She put her hands on her hips and stared at him, daring him to challenge her again.

He felt small and tired. He’d tried to project his anger onto this girl and she’d opened up to him. In her eyes he saw a mirror of his own horror.

He rubbed his eyes again and closed them. When he opened them he saw her gaze had softened. She held out both hands to him, and he took her tiny fingers in his and stood.

‘We go somewhere quiet. Not this Africa place. We talk, OK?’ she said.

Mike nodded and let the girl lead him outside.

A warm rain was falling and the busy street was choked with yelling drunks and tuktuks beeping their horns. He held her hand as they walked. He would ask her about Cambodia, about Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. He wanted to know how she felt – did she want revenge? Did she feel the need to make sense of the madness that had gripped the men who had taken her family from her?

Ironically, he felt more relaxed now that he was thinking about Cambodia. He’d thought Thailand might allow him to escape the horrors, but the truth was that he didn’t want to escape, didn’t want to forget. He was driven by the need to understand how people could massacre each other, what provoked neighbour to slaughter neighbour.

His head was beginning to throb. Bloody Singha. The stuff tasted like it was fifty per cent formaldehyde. He either needed another one, or a glass of water and a couple of paracetamol. He doubted he’d get the latter.

He was drunk. Too drunk. Something was spinning around his mind – something she’d said inside the noisy bar, but he couldn’t quite remember what it was, or why it was nagging at him. He looked down at the ground as he tried to concentrate, letting her lead him. When he glanced up he saw they were well away from the bustle of the main street.

‘Where we going?’ he slurred.

She looked back at him. ‘Quiet place. You say you want talk – we talk.’

‘OK.’

What had she said that he wanted to ask her about first? It seemed important.

An Asian pop song started playing as a ringtone. The girl reached inside her singlet top and took the mobile phone from her bra. She flipped it open and spoke into it in Thai. She looked back at him again.

He stopped walking while she spoke, her words staccato, whispered.

It suddenly dawned on him. ‘Rwanda.’

She snapped the phone closed. ‘What you say?’

‘Rwanda.’

The girl started walking, her platform heels slapping the rain-slicked pavement with every step.

‘Hey. Wait,’ he called after her, hesitating. ‘When I mentioned Africa before, and a little country in the middle of nowhere where people killed each other, you said, Rwanda.’

She stopped but didn’t look back. ‘Everyone know ’bout Rwanda.’

‘The genocide happened in 1994. You wouldn’t have been more than a year or two old. I could have been talking about Burundi, or the Democratic Republic of Congo or half-a-dozen other places in Africa.’

‘It lucky guess.’ She turned and started walking back to him. She forced a smile and let her hips speak as she swayed expertly along on her platforms.

Mike took a pace back and held out his arms. ‘No.’

‘Come to me, baby. We talk.’ She reached out and grabbed his hands. ‘Maybe we boom boom later, yes?’

He brought his arms up sharply, breaking free from her grip. She took two quick steps and pressed herself against him, her tiny breasts flattening against his sweaty belly.

‘Get away from me.’

‘No, baby. I want you.’ She reached up and put her palms on his chest.

‘I’m going to ask you one more time. How did you know I was talking about Rwanda?’

She peered around his body, which dwarfed her. ‘It no matter.’

‘It does matter. I’m going.’ He turned and was about to step off the kerb and onto the road when he saw the sedan come around the corner. He heard the whine of its gears as the driver changed down, and the growl as he stamped on the accelerator. Bloody maniac. No headlights either. The girl was behind him. Screw her. Perhaps it had been a lucky guess, but it was too much of a coincidence. The stakes were too high. He needed to get away from her. It could be a trap, someone wanting to know what he knew. But here? He shook his head. No way.

The car screamed down the street. Mike willed it to go faster so he could cross the road and get away from her cloying touch, and the smell of her cheap perfume and sweat. He felt her little hands on his back. ‘Enough!’

When he spun around to confront her, he saw the change in her eyes, the set of her pursed mouth. The gap between the top of the kerb and the road was bigger than an Australian street, probably to cope with the monsoonal rains. As she pushed him, hard in the ribs, he started to topple. Silly bitch would kill him if he fell in front of a speeding car. ‘No!’

1

South Africa, one month later

A Highveld storm, Liesl Nel thought, was like watching the end of the world, the glories of heaven and the horrors of hell fighting it out across the skies, all played out in three-hundred-and-sixty degree Imax and surround sound.

Liesl drew on her cigarette, closed her eyes and let the nicotine and the deep-bass boom of the thunder soothe her. The lightning penetrated her closed lids, the flicker and the noise that followed reminding her of muzzle blasts and gunfire. When she opened her eyes, the faux Tuscan villas of the estate and the rolling hills beyond were seared white with a burst of light.

She recalled, as hard as she tried not to, how she’d actually thought bodies looked artistic sometimes; the white lime turning the grimacing, reaching cadavers into marble statues. Back then, the camera’s viewfinder had been her filter, distancing her momentarily from the reality of the mass grave, though it couldn’t block out the smell. That’s when she’d taken a cigarette from another shooter, an army photographer, started smoking and stopped believing. That was in 1994. She hadn’t stopped smoking – or started believing again – since.

Liesl exhaled and hoped the chill of the rising wind and the first fat drops of rain would blow away the memories and wash away the guilt. It was coming back to Africa that did it; it resurrected the bodies every time. An up-market walled estate on Johannesburg’s western outskirts was a world away from the guns and the graves and the killing gangs in Rwanda, but it was still Africa out there, beyond the honey-rendered walls topped with electric fencing. The biometric fingerprint security at the gate and the roving armed response patrols wouldn’t save her. She was already dead.

A rap on the window pane startled her, like the pop-pop-pop of an AK on automatic. She started and spun around, and saw Sannette laughing. She was tapping a champagne flute against the glass of the French door. ‘One more, hey, before we leave?’

Liesl checked her own glass. Empty. ‘Ja, why not.’ Booze wasn’t the answer, of course, but it sure as hell helped.

*

A lion roared, but not like in the movies. Richard thought it was more like a wheezy, bronchial groan. Nothing in fiction could portray this continent as it really was. The cat was a long way off, and early with its call – perhaps eager for sex or food. A purple-crested turaco squawked and clucked in the tree above the thatch roof of the surgery. That was more his Africa: annoying birds rather than kings of the jungle.

He looked at the note on his desk. He’d scrunched it into a ball but hadn’t been able to toss it in the bin yet. He unfolded it, smoothing it out on the desk calendar blotter left by some pushy drug-company sales rep. 18h00, ten minutes. J.

He checked his watch and scratched his stubbled chin. It was five-thirty or, as a South African would have written it, 17h30. He picked up the piece of paper and held it to his nose, drawing in his breath deeply. It wasn’t perfumed – that only happened in films, didn’t it? But he didn’t need the scent, or the reminder.

‘Mrs van der Merwe is outside, Doctor,’ his receptionist, Helen, had said two hours earlier, after she’d knocked and stuck her head around his door.

Helen’s husband was a trails guide in the Kruger National Park, as Janine van der Merwe’s had been until he’d transferred to the SANParks criminal investigation division. These days he tracked poachers, not game. Rhino poaching was getting out of control in the park and Lourens, Janine’s husband, was away from home a good deal. Lourens was used to dealing with predators, of the two- and four-legged variety, and he was invariably heavily armed.

‘Tell her I’m busy with a patient.’ He had, in fact, been trying to tie a fishing lure.

Helen had raised her eyebrows. He’d stared at her until she’d closed the door. Bloody hell, he realised, it would be all around the staff village by nightfall. He should have seen Janine there and then and told her that it was over, that he’d made a mistake.

Helen had knocked on his door again a few minutes later. ‘She’s just left. I told her you were still busy with a patient. She left you this.’ Helen had passed him the note.

Richard folded it now, instead of crumpling it, and wrapped it around two of his fingers. What to do? he asked himself. He knew the right answer, but he also knew what she wanted him to do. He checked the time once more. Five thirty-two. Decision time soon. There was another knock and Helen entered. ‘I’ve got a tourist in the waiting area, just come in. He thinks he’s been bitten by a cobra but he’s not quite sure.’ Helen pronounced the last three words in what she no doubt thought was a good approximation of an upper-class English accent.

‘How can you not be quite sure if you’ve been bitten by a snake?’ he muttered, slipping the note into his top pocket. Helen shrugged, but she’d seen the gesture. She handed him the form with the patient’s particulars.

He wondered if she had read the note. Helen was snoopy and gossipy, but would she read a note from a patient to a doctor? Probably.

The British tourist, Raymond Philpott, aged twenty-two, newspaper journalist from Enfield, had walked to one of Skukuza’s camping ground ablution blocks, drunk after a lunchtime braai and too much beer in the sun.

He slurred his words. ‘It – the snake – was on the door handle. I thought it was a bootlace or something, but when I reached out to open the door, it reared up and struck me.’

‘I see,’ Richard said, adjusting the lamp on his table and holding the man’s hand up close to it. ‘Big snake, was it?’

‘Big enough.’ He could tell the tourist felt foolish. ‘Like a bootlace, not a shoelace.’

‘They’re quite active this time of year. It’s the summer heat. Most of the snake incidents I deal with are when someone surprises a Mozambican spitting cobra and it spits in their eye. We don’t get many bootlace-sized snake bites. What colour was it?’

‘Brown. Maybe green. Greeny brown. What do you think it was? My mate thought it might be a cobra.’

‘I can’t see any evidence of a laceration, not even a scratch, and if you had been bitten or grazed by a poisonous snake you’d be in a good deal of pain.’

‘Umm, it feels a bit numb,’ Philpott said.

Probably the dozen beers in the sun, Richard thought. The young man’s skin was red and his eyes were bloodshot. He’d had a fright, but what he needed now was a litre of water and a lie-down. Richard told him as much.

‘You’re English?’ Philpott said.

Richard nodded.

‘How did you end up here?’

Richard sat back in his chair and clasped his hands across his stomach. ‘I ran away from the UK to avoid an embarrassing and potentially costly malpractice litigation suit brought on by my addiction to prescription drugs, and this was the only job I could get, giving malaria tests and bandaids to tourists and staff in a dead-end backwater of Africa. The billings are rubbish, but I do get a nice house in the staff village. I had a leopard in a tree in my front yard last week.’

The man blinked his red eyes a couple of times, then started to laugh. ‘You’re joking, right? Nice one.’

‘No, I’m not joking. The leopard was in my front yard. Will there be anything else?’ Richard asked. He could see the drunk man was trying to retrace the last couple of steps of the conversation in his mind.

‘You were joking about the malpractice stuff, right … and the drugs?’

Richard said nothing.

‘Well, if you think I’m all right, I’ll be off then,’ Philpott said. He seemed to have forgotten all about his snake bite. Richard saw him out and told Helen to draw up his bill. He thought about Janine, and how weak he was.

‘Goodbye, Raymond. Watch out for snakes in the gents, all right?’ he said to the man as he left. He checked his watch. Ten minutes to six. He could make it, and see Janine. Sometimes honesty was the best policy. He’d tell her it was over. Or perhaps he’d do her over the bonnet of her car.

Virunga Mountains, Democratic Republic of Congo

‘Vite!Vite!’ They called him ‘Vite’ because he was speedy.

Vite ran through the banana plants as fast as he could, but he was young and his legs were short. The illegal charcoal makers who chased him yelled to each other as they tried to outflank him. He screamed in fear. They had just killed his mother with a bullet.

Vite and his family had stumbled into the tree poachers’ operation on the edge of the rainforest and the charcoal makers had seen them both as a threat to their work and an opportunity to make some good money. The men operated on the edge of the national park, illegally cutting down native trees and gums that had been planted for timber. Charcoal was the main source of heating and cooking fuel for millions of people and there was never enough of it. The men dug big pits and set their timber on fire, then covered it with mounds of earth and let it smoke until the virgin timber was turned to black charcoal. Vite and his family had also been raiding the gum plantation – for food – so they were competitors as well as a valuable commodity in their own right.

‘A droit,’ one of the men yelled.

Another laughed at the chase. ‘Oui. Il est là!’

Fronds lashed at his face and ears and he panted as he moved through the shadowed labyrinth between the trunks of the trees. A low-hanging bunch of fruit smacked him. He shrieked. There was more gunfire further behind him.

Vite had seen his mother falling, her arms flailing, as the bullets knocked her down. The rest of his tribe had bellowed and cried and scattered as fast as they could. His father, a giant fellow, had charged at the men and tried to retrieve the body of his mother, but the men had opened fire with guns, forcing him and the rest of Vite’s family to seek refuge back in the rainforest. Vite had been cut off and his only option was to run into the banana farm. Now they were after him.

The straggly lines of banana plants gave way to the thick green orderly maze of a tea plantation. Pickers with baskets on stooped backs straightened to watch the chase, a welcome break from the drudgery of their job. The tea shrubs were up to the waists of the men who chased him, but Vite was small enough to be completely hidden by them. He slapped the shrubs out of his way as he ran and ran.

The men called to each other, confused now, and even though Vite had the cover of the tea shrubs, he was getting further and further from his home on the mountain. The men had spread out in a skirmish line and some of the tea pickers had seized the excuse to set down their baskets and bolster the ranks as beaters. They yelled and whistled. Vite ran down the hill then up the opposite side. His small heart was pounding and he had stopped screeching to conserve his breath. He had never been this far away from his troop before.

At the crest of the next hill he came to a road. He considered crossing it and pushing further into the tea plantation, which continued just as thick and green on the other side, until he spotted a line of tin-roofed timber huts off to the right. Smoke curled from a pipe in one of them. It would be risky, turning right and running along the gravel road, but it might allow him to outflank his pursuers and double back towards the safety of the forest.

Vite took the road, which soon led him between rows of farm workers’ huts and past a smouldering fire. A woman in a brightly coloured wrap, her head in a turban, yelped with surprise as she emerged from her home and saw him darting across her path.

The woman stood there for a second, confused by the sight and the noise, but ducked back into her hut when the two men came pounding along the muddied track that led from the banana farm. One carried a panga, the other an AK-47. The woman knew the killing power of the weapons, each as terrible as the other in its own way. The men slowed. She pointed down the trail. The first man nodded and they set off.

Vite watched this all happen from his hiding place beneath a stack of old mealie sacks behind the hut next door to the woman’s. He’d darted around the building as soon as he’d passed her and she hadn’t noticed. His little chest was heaving. He could move as fast as his name implied, but not for long. He was used to spending his days close to his mother, perhaps playing with his cousins, tumbling in the grass or climbing trees. He was exhausted and he was hungry.

A dog growled. Vite scrambled towards the mudbricks, dragging a sack with him as partial cover. The dog was mangy, its protruding ribcage studded with fat black ticks. Drool dangled from its bared teeth. It barked.

‘Silence,’ the woman called. She rounded the hut and looked down at him, then back along the pathway where she had sent the men. She had seen his escape, but she had not betrayed him. The dog growled again and the woman slapped it on the snout. She reached down and Vite cowered from her. He was too tired to run, though, and surrendered to his fate as she placed her hands under his arms and lifted him.

Vite had no idea if there was anyone in his extended family left alive or free. He squealed with hunger and terror, but as the woman brought him to her he started to calm. He clung to her, as he would have done to his mother if she had been there. She was all he knew, and he missed the protective embrace of her long arms. This woman’s arms were not as long, and they were not covered in warm hair, but they were black. Vite nestled into her.

The woman made cooing, soothing noises and told him, in French, to be quiet, for his own safety. Vite laid his head against her breast. In the distance was the occasional pop-pop of gunshots, but these sounds soon died down. She held him away from her and looked into his black eyes. ‘What am I going to do with you, little gorilla?’

Sydney, Australia

Sitting in the Qantas club at Sydney Airport, as unseasonal rain lashed the window, she tapped on the screen of her iPhone and updated her Facebook status: Carmel Shang now has a chimp named after her. How good is that?

It was silly, she knew, to post such a cryptic message. Her thirty-nine friends – a pathetic number according to her niece Chloe – would all comment now, asking for more details. It would start up a chain of inane small talk, but Carmel took happiness where she could find it in her life, and Henri’s email had made her smile.

There would be little joy waiting for her back in Africa, other than the visit to Henri’s wildlife rehabilitation centre in Livingstone on the Zambian side of the Victoria Falls. Although she’d been to the continent fifteen times, nearly always for work, Carmel had never been to the falls, so she was excited about seeing them. And about meeting Henri in the flesh.

They’d first met online, on a web forum called ‘Safaritalk’, where like-minded people with an interest in Africa and wildlife conservation commented on issues and socialised virtually. Carmel had mentioned that her work had taken her to Rwanda and Tanzania, and Henri had commented that he had grown up in Rwanda. He’d contacted her, via a private message, to ask her what she thought of the country these days, post the genocide of the mid-nineties, and from then on they’d been in regular contact.

Henri had asked about her background, saying that Shang didn’t sound like an Australian name to him. She’d explained that she was an ABC – an Australian-born Chinese, the descendant of a Chinese man who’d immigrated during the nineteenth-century gold rush and married a Scottish woman, and that she was as Aussie as they came.

Henri told her he was trying to get his privately run wildlife rehabilitation centre to a point where he could open it to the public, and when she’d enquired about his funding arrangements and offered to help in whatever way she could, he’d invited her to visit next time she was in Africa. He’d cajoled her a bit, and she’d relented. It would do her good, she thought, to spend a bit of time with someone committed to doing good in Africa, rather than just dwelling on past horrors, as she usually did.

Plenty of people, herself included, had tried to make sense of the mass slaughter that had taken place in the tiny central African country, and to try to apportion blame, but Henri had proudly, and at times controversially, stated time and again that he cared more for the innocent animal victims of Rwanda and its neighbouring countries than he did for people who would take up arms against their friends and neighbours.

A little talk bubble flashed up on her screen, informing her that Henri Bousson had just commented on her status. She worked out that it must be about midnight, the night before, in Zambia. She opened the message. You deserve to have a chimp named after you. Thank you for your support.

She smiled. She hadn’t done that much, only donated a few hundred dollars. The chat box popped up on the bottom right-hand corner of her screen. It was Henri. She experienced a little jolt of surprised pleasure.

Hi, he typed. Where are you, at the airport?

Yes, she replied. Late there?

Oui.

She didn’t know what to type next. Her flight would be boarding soon. She would arrive in Johannesburg at about four in the afternoon, stay overnight at the D’Oreale Grande at the Emperor’s Palace casino near the airport, then get the Commair flight to Livingstone, Zambia, at eleven the next morning.

I’m looking forward to meeting you, he messaged, filling the void.

Me too.

A lot.

An announcement came over the club’s PA, telling passengers the flight to Johannesburg was ready for boarding. Carmel picked up her laptop bag and hooked it over the handle of her small wheeled suitcase. She only ever flew with carry-on – it was too much of a risk and a hassle hoping that checked-in baggage would make it past the Johannesburg baggage handlers intact, let alone all the way to Zambia, Kenya or Rwanda. She held out the phone as it needed to be almost at a full arm’s length these days in order for her to see, and tapped the screen as she walked out of the club and onto the escalators.

Me too.

2

Richard took a sixpack of Windhoek Lager dumpies from the surgery fridge where the blood and drugs were kept. Whichever way it went with Janine, he wouldn’t want to be stone-cold sober.

Helen had left for the day, which saved him having to answer questions about what he was doing that evening. He still didn’t know for sure. The Skukuza doctors’ surgery was set on the staff village side of the fence separating the national parks’ employees living area from the public rest camp, and the surgery could be accessed by guests in the camp via an entrance on their side. Richard walked through it and into the public area. He’d left his car on the camp side as he had driven to the workshop behind the petrol station to get his flat spare tyre fixed during his lunchbreak and then parked on the camp side to get back in time for an appointment. As he walked to his old Discovery 2, he freed a green bottle from the plastic wrap and used the opener on his key ring to crack it. He’d finished the first before he had driven past the big thatch-roofed Skukuza reception building. He took it slow driving through the gate, as the nightly stream of self-drive tourists hurrying back to camp before the dusk curfew was pouring in. Once he was over the annoying speed bumps he shifted up through the gears to fourth and opened another beer, this time with an opener he’d riveted to the dashboard. As he approached the four-way stop, he’d finished the second bottle and was starting to think a little clearer.

Richard’s phone beeped. He fumbled in his top pocket then checked the screen of the cheap Nokia. Low Battery, it flashed, then beeped again and died. ‘Shit,’ he mumbled. He’d plugged it in this morning, but the phone was old and the battery barely held a charge these days. Not good for the camp doctor to be out of contact, but the faux-snakebite victims could damn well wait half an hour while he tried to sort his life out.

He could have turned right before the stop sign and driven through the Skukuza staff village, but it didn’t really pay for his patients to see their GP drinking and driving. Sticking to the public roads took a bit longer, but he could drive faster. Although the park’s speed limit was fifty kilometres on the tar roads, he had a sticker on the back of the Discovery which showed he could drive at sixty-five. It was handy for emergencies and pressing appointments, such as Janine van der Merwe’s breasts.

Richard flicked the top off the third beer as he followed the road towards the Paul Kruger gate. He saw the traffic cop’s bakkie poorly camouflaged in the bushes and flashed his lights a few times. The national parks traffic enforcement officer, who was there to catch tourists speeding to leave the park via the Kruger gate, stepped out onto the road to flag him down, but then raised a hand and smiled and waved when he recognised the doctor’s vehicle. Richard raised his bottle to him in salute, and the man grinned wider. He knew Ezekial was an alcoholic – took one to know one. Richard had diagnosed himself as borderline, though, which gave him a small measure of comfort. He reflected on what he’d said to Raymond Philpott and smiled. ‘Better than being a drug addict, I suppose,’ he said to himself.

The beer tasted good and was altering his mind nicely. He’d left the surgery with noble intentions, but they were fading. Fast. He floored the accelerator and crossed the N’waswitshaka River. He thought about Janine van der Merwe’s nipples. They were, quite simply, astounding. He’d never, in any examination, professional or not, come across any so perfectly formed, free of lumps and blemishes, and as long and as hard when erect. She liked him to play with them when they kissed. He’d take one between his first and second fingers, teasing it, holding it like a cigarette, and brush his thumb along the tip.

‘For fuck’s sake,’ he said to himself as he finished the third beer. He slowed as he neared the turn-off. What was he doing?

He was becoming aroused. His hormones had always ruled his life. He shifted down to second. The smart thing, he knew, would be to turn around and go home, to stand her up. Perversely, that was also probably the wrong thing to do. Which, he wondered, was the greatest moral misdeed he’d committed with and in relation to Janine: sleeping with a patient, sleeping with another man’s wife, breaking off a relationship with a woman who’d told him she loved him and would leave her husband for him, or standing her up now she wanted to talk again? He was a cad, no doubt of it, but he wasn’t rude. Richard sighed. The right thing, of course, would be to meet Janine and break it off, again, once and for all.

He turned left onto the gravel road that led to Ten Minutes – it was a place she’d specified in her note, not a time. Richard knew it well, as did everyone in the Skukuza staff village, so it wasn’t a good enough code to fool his nosy receptionist. The broad sandy stretch of non-perennial riverbed was exactly ten minutes’ drive from the staff village and it was a favourite hangout for bush braais and sundowner drinks after work. The river usually only flowed once a year; the rest of the time there were barely a few pools, which staff kids loved to splash about in. It was like a beach in the middle of the African bush, complete with the odd lion, hyena and leopard patrolling the shore. When he’d first taken the job as the Skukuza GP, Richard had thought it insane to let children play in such a place, but Africa had a way of breeding contempt for danger through familiarity. He hadn’t been lying to Philpott when he’d told him he’d had a leopard up a tree in his front garden the previous week. When he’d arrived at Skukuza a year ago, he would have freaked out, but last week he’d sat on the porch taking pictures of it, a cooler box full of beers next to him.

Janine and Lourens had driven around to his house, ostensibly for a look at the leopard, as had several of his neighbours once the word had got around. When Lourens had gone to the toilet Janine had taken the front of Richard’s bush shirt in her hands and tongue-kissed him. He’d ground against her, returning the passion and the need. Technically, he reflected as the Discovery bounced along the track, the last minutes of the ten ticking away, he hadn’t had sex with Janine, but it was a bit of a Bill Clinton definition. In the past few weeks they’d done pretty much everything else. There hadn’t been time in the kitchen while Lourens was relieving himself. He smiled, then shook his head to clear the beer fuzz.

‘Fuck it.’

He tossed the empty bottle on the floor of the truck, cracked open a fourth and took a sip before putting it sensibly in the cup holder. He knew what she wanted here in the last golden rays of light, on a blanket she’d probably bring with her. When Lourens wasn’t out in the field he often worked nights in the investigations office, monitoring teams in the field. He was fighting the good fight against rhino poachers and his wife was going behind his back. Richard alternated between his ever-present desire for a female body and disgust in himself. He’d served with soldiers in the British Army who’d received the dreaded Dear John letter and back then he hadn’t been able to imagine what sort of a man would do that to another man. Now he knew. He had called her and suggested they end the relationship before it went further, but now she wanted to see him again.

‘Enough,’ he said aloud in the Land Rover as his headlights picked out Janine’s Isuzu bakkie next to a mound of sand that had been excavated from the river. Richard parked behind a front-end loader. SANParks was quarrying sand to spread on the tar roads. They did it every summer to minimise the effect of the seasonal rains but this January the heavens had brought a deluge that had washed away roads and bridges. The park was a mess and the N’waswitshaka was still flowing strongly even though the floods had mostly subsided. The Isuzu’s driver door opened and a long leg, barefooted, swung out.

Janine was pushing forty with two kids, and she pretty much melted his resolve when he saw her in those denim short shorts. He knew she jogged and worked out every day, did whatever she could to relieve the boredom of being at home and unemployed in the staff village. She’d done a degree in marketing or PR or some such thing, he recalled, but affirmative action had closed off most of the plum jobs that once would have been available to white rangers’ wives. Janine probably needed someone to tell her she was still sexy, still desirable, and she was – very much so.

Richard ran a hand through his mop of damp salt and pepper hair. He took a moment to consider his current situation. He’d pretty much made a cock-up of his entire life. Sure, the shrinks put the blame on other places, other people, other times, but there was still enough of the soldier in Richard to know that he could have pulled himself together, could have done better. He was a disgrace to his family and a poor excuse for a doctor. And although he knew perfectly well that it was wrong, all he wanted to do was have sex with this woman right now. He took another sip of beer then replaced the bottle in the holder and got out.

He thought he saw her tongue moisten her lips as she walked towards him, hips swaying, feet squeaking in the sand. She brushed a strand of dyed blonde hair from her face. He wasn’t keen on sand so his mind drifted to the bonnet of her pickup.

‘Richard …’ she said, stopping just out of reach.

For once in your life, he tried to convince himself, do the right thing. ‘Janine …’

‘No.’ She closed the gap between them and reached out to him, putting a French-tipped finger to his lips. He shut his eyes. He was incapable of doing the right thing, he knew it. He smelled her perfume, opened his eyes and felt his body surrendering, betraying him. Why fight it? She wants it. She probably wasn’t getting it from Lourens and, if the truth be told, the man was an arrogant, rude bore. ‘Don’t say anything, Richard,’ she whispered, ‘just listen to me.’

He nodded. He kept his hands to himself. He could do slow.

‘Richard, I’ve wanted you since the day I met you, but …’

His eyes widened. But?

‘Richard, this is wrong. I can’t be unfaithful to Lourens and –’

They both turned at the sound of a big engine revving hard. They stepped back from each other and Richard felt himself deflating – mentally and physically. He raised a hand to shield his eyes from the glare of the spotlights mounted on the approaching Land Cruiser bakkie’s bullbar. Two Africans in green bush uniforms, R5 assault rifles slung over their shoulders, stood in the back of the truck. It sped towards them and for a moment Richard wondered if the driver intended to run him down. The vehicle stopped just in front of him, the door opened and Lourens van der Merwe, all six foot three inches and ninety-five kilograms of him, climbed out. Richard had given him his annual check-up two weeks earlier. He was all muscle and very little fat. There was nothing wrong with the man, which was a worry for Richard. He stood his ground.

‘Doc, what the hell’s going on, man? I tried your phone five times but it’s switched off. Aren’t you supposed to be on call?’

‘I am. Problem with …’

Lourens waved away the excuse. ‘I checked your house then called Helen. She told me she thought you might be here.’ He looked at his wife for four seconds, no more, his huge hands bunched into fists at his side; then he looked back at Richard.

Richard was ready. He’d ‘milled’ during parachute training in the army – put on gloves and tried to beat the shit out of a fellow recruit who gave as good as he got until the drill sergeant told them to stop. It was all about developing controlled aggression. He’d also boxed a bit for the regiment. He was, of course, older and flabbier now, and Lourens had it over him in weight, muscle and youthfulness. What was coming, though, would do him good, in a masochistic kind of way. Perhaps a few bruises from Lourens might assuage the guilt he occasionally felt for the other husbands he’d wronged.

‘We’ve got a man down. Anti-poaching patrol found some Mozambican rhino poachers. We drilled two of them and we’re in pursuit of the third, but they got one of my men. He’s taken an AK round to the chest. Chopper’s coming and they’ll fly him to Nelspruit.’ Lourens pointed his right finger like it was a pistol, and fired at Richard’s heart. ‘But I want you on board.’

Richard nodded. ‘I’ve got my bag in the back of the Discovery.’

‘Fetch it. You’re coming with me. You can pick up your vehicle later.’ Lourens turned and walked back to his truck. He reached inside and talked into a radio handset, in Afrikaans. Richard got his medical bag – an old army medic’s pack – and hoisted it into the back of the Land Cruiser. His Afrikaans was basic at best, but he gathered Lourens was talking to the national parks helicopter pilot. Lourens got into the front of the bakkie and motioned for Richard to get in the passenger seat. Lourens looked at his wife and spat out a few more words that Richard guessed meant: ‘I’ll deal with you later.’

‘Lourens …’ Richard began as the Afrikaner swung the truck around in a three-point turn and gunned the big four-litre engine for all it was worth.

Lourens looked straight ahead into the darkness that had descended on the bush. ‘Unless it’s about my man, I’m not interested. The helo will pick you up on the tar road and you’ll go. And my advice to you, Doctor Richard Dunlop, is that you keep my man alive and that he stays alive, otherwise people will find out that you weren’t on call when we needed you.’

Richard nodded.

There wasn’t room for a helicopter to land safely at Ten Minutes, so Lourens had organised the landing to take place on the tourist road nearby, which was turned from night into day by the helicopter’s landing light. The journey to the pickup had been quick, leaving no time for excuses or explanations. The helicopter settled. Richard grabbed his backpack from the rear of the Cruiser. ‘Are you coming?’ he yelled to Lourens over the noise of the chopper’s whining engine. The pilot gave him a thumbs-up, indicating it was clear for him to approach.

‘No. I’ve got to get back to the ops room. We’ll talk later. Save my man.’

Richard nodded.

He climbed into the chopper and buckled his seatbelt as the pilot lifted off. Richard looked down and saw Lourens was already driving the short distance back to Skukuza. As the pilot, Andre, banked he noticed the headlights of Janine’s bakkie weaving through the bush. Richard burped beer and the pilot grinned and shook his head.

He’d been for a ride in this helicopter before, out with one of the vets who was darting rhino. The parks people were putting passive transponders in the rhinos so they could track them because a record number had been poached in Kruger the previous year. As a doctor, Richard couldn’t understand how people could be so well educated yet still believe in the mumbo jumbo of traditional medicine. Rhinos were being slaughtered for their horns, not to produce a fabled aphrodisiac but rather for the relief of fever and, according to the latest rubbish, as a cure for cancer. The illegal trade in wildlife products was big business and the perpetrators were becoming ever more organised and ruthless.

Through his headphones Richard heard the pilot radioing the anti-poaching patrol on the ground telling him he was inbound with the doctor and would be at their location in four minutes.

‘They’re not far from Renoster Kopjes,’ Andre told him through the intercom. ‘These guys are getting more desperate by the day, hey.’

Richard gripped his bag and looked down at the faded camouflage pattern. Funny, he thought, how the combination of the whine of the jet engine and the smell of the burning fuel and the colour of his bag could produce such a response. His skin felt clammy and sweat pricked at his underarms. He felt his heart beating faster. He didn’t know if he could do this, didn’t know if he could save this man. He saw a strong hand-held spotlight being strobed on and off below, guiding them in. The flickering light intermittently caught the shirtless black man on the ground and the glint of the blood as the helicopter began its descent.

Richard saw a movement in the cone of the landing light ahead. ‘Hey, look there!’

The pilot nodded and radioed the leader of the anti-poaching unit. ‘I’ve got movement to my front, one hundred metres. One male with a rifle. Looks like an AK, over.’

Richard knew the dilemma. There would be men on the ground wanting the helicopter to follow the fugitive, perhaps the man who had wounded their colleague. At the same time their chief concern must be for the wounded man.

The running man stumbled then fell and, still trapped in the light as the helicopter continued its descent, he turned and pointed his rifle at them. Richard saw the muzzle flash just as the pilot did. ‘Holy shit,’ the pilot said.

‘Put us down,’ Richard barked. ‘There’s a man dying down there.’ If it was a chest wound, that wasn’t an exaggeration. The pilot nodded and switched off the landing light.

Richard hoped Andre, the young man flying the helicopter, was good enough to land by the comparatively weak illumination of the spotlight that was now being held steady on the road. Richard thought the man holding the light was brave as the startled poacher might aim for it. More likely, though, the Mozambican was running as fast as he could. As they touched down, bumping as the skids hit one after another, Richard heard gunfire over the scream of the rotors. Some of the patrol were in pursuit. He squeezed his eyes shut and forced out the images of the dead who rose up from his nightmares. Now is not the time, he told them, now is not the time.

‘Doc … Doc!’ Andre punched him on the arm. ‘Come on, man, get out. I’ll keep the engine burning. Go get him, Doc.’

Richard opened his eyes, nodded and grasped the door frame. One of the patrol members, his face streaked with dirt and sweat, his uniform wet with blood, had already opened the door and was beckoning to him. Richard dragged his pack out and ran, bent at the waist, to where the wounded man lay. He unzipped a side pocket of the pack, pulled out a box of disposable gloves and snapped on a pair as the patrol leader told him what had happened. One shot; the bullet had passed through the man’s chest and out his back, tumbling on the way as was typical of an AK round, not taking time to smell the roses.

The man was in his mid-twenties, Richard guessed, his abdominal muscles defined, shiny and hard as chiselled stone. He was fit. He’d need to be. Richard peeled back the big, blood-soaked pad of the wound dressing. The man wheezed and winced, as the blood gurgled and frothed from the hole. Sucking chest wound.