Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polaris

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

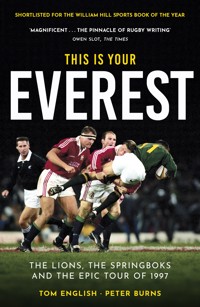

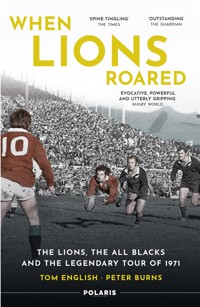

By 1971 no Lions team had ever defeated the All Blacks in a Test series. Since 1904, six Lions sides had travelled to New Zealand and all had returned home bruised, battered and beaten. But the 1971 tour party was different. It was full of young, ambitious and outrageously talented players who would all go on to carve their names into the annals of sporting history during a golden period in British and Irish rugby. And at their centre was Carwyn Jones – an intelligent, sensitive rugby mastermind who would lead his team into the game's hardest playing arena while facing a ferocious, tragic battle in his personal life, all in pursuit of a seemingly impossible dream. Up against them was an All Blacks team filled with legends in the game in the likes of Colin Meads, Brian Lochore, Ian Kirkpatrick, Sid Going and Bryan Williams. But as the Lions swept through the provinces, lighting up the rugby fields of New Zealand the pressure began to mount on the home players in a manner never seen before. As the Test series loomed, it became clear that a clash that would echo through the ages was about to unfold. And at its conclusion, it was obvious to all that rugby would never be the same again.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 427

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WHEN LIONS

ROARED

WHEN LIONS

ROARED

THE LIONS, THE ALL BLACKS AND

THE LEGENDARY TOUR OF 1971

TOM ENGLISH

PETER BURNS

First published in 2017 by

POLARIS PUBLISHING LTD

c/o Turcan ConnellPrinces Exchange1 Earl Grey StreetEdinburghEH3 9EE

in association with

ARENA SPORT

An imprint of Birlinn LimitedWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QS

www.polarispublishing.comwww.arenasportbooks.co.uk

Text copyright © Tom English and Peter Burns, 2017

3

ISBN: 9781909715523eBook ISBN: 9780857903433

The right of Tom English and Peter Burns to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Polaris Publishing, Edinburgh

Printed in Great Britain by Clays, St Ives

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PROLOGUE: Boy, could they play

ONE: We all wanted to be Carwyn James

TWO: Am I boring you, you big prick?

THREE: A fairly rude awakening

FOUR: That was the end of Ernest Grundelingh

FIVE: A thinking man’s game

SIX: Des Connor was a nutter

SEVEN: He squirmed and wriggled – couldn’t take it anymore

EIGHT: Athletic Park – mindboggling

NINE: A dagger in the heart

TEN: Canterbury – it was just a bit of biff

ELEVEN: Like the Luftwaffe coming in

TWELVE: They regarded me as a sissy

THIRTEEN: I was a farm boy – tough

FOURTEEN: Up the mountain, dead boar round my neck

FIFTEEN: JPR saved my life

SIXTEEN: Rumble in the bay

SEVENTEEN: The Eighth Wonder of the World

EIGHTEEN: The King abdicates

NINETEEN: There is a great loneliness upon me

TWENTY: No bugger wants to know you

TWENTY-ONE: The Immortals

EPILOGUE: ‘You wait until you play . . .’

BIBLIOGRAPHY

In memory of Carwyn, Doug, Gordon, Mervyn and Alastair

Legends forever

List of Illustrations

The 1971 Lions party at Eastbourne. Back row: Dr Doug Smith (manager), Mike Gibson, Chris Rea, Ian McLauchlan, Fergus Slattery, Sandy Carmichael, Derek Quinnell, Mike Roberts, John Spencer, Sean Lynch, Delme Thomas, Mick Hipwell, Peter Dixon, Carwyn James (coach). Middle row: Arthur Lewis, Willie John McBride, Mervyn Davies, Gordon Brown, John Dawes (captain), Bob Hiller, John Bevan, Alistair Biggar, John Taylor. Front row: Ray McLoughlin, Ray Hopkins, John Pullin, Gareth Edwards, Barry John, Frank Laidlaw, Gerald Davies, JPR Williams, David Duckham

The 1971 All Blacks at Dunedin. Back row: Ken Carrington, Richie Guy, Ian Kirkpatrick, Peter Whiting, Alan Sutherland, Alex Wyllie, Bob Burgess. Middle row: Bob Duff (selector), Howard Joseph, Jazz Muller, Alan McNaughton, Ron Urlich, Tane Norton, Bryan Williams, Bruce Hunter, Pat Walsh (selector). Front row: Ernie Todd (manager), Sid Going, Wayne Cottrell, Colin Meads (captain), Fergie McCormick, Bill Davis, Ivan Vodanovich (coach)

The coaches going head-to-head in the series, Carwyn James (left) and Ivan Vodanovich (right).

Fergie McCormick unleashes the irresistible force of Bryan Williams against Transvaal in 1970. Photosport NZ

Carwyn begins to espouse his tactical philosophies for the tour as the party take a break in training.

Tour captain John ‘Syd’ Dawes carries his manager, Doug Smith, during a training run. As Mervyn Davies recalled, ‘The threat of having to carry Doug the length of the pitch for a training misdemeanour helped focus our collective minds.’

After the shock defeat to Queensland, the Lions get their first win on the tour against New South Wales in Sydney. Delme Thomas rises above the challenge of New South Wales’ Owen Butler, watched by John Pullin (number two) and John Howard (number one). Getty Images

Having been crunched by Mervyn Davies, New Zealand’s talisman, Colin Meads, has his ribs bandaged during King Country/Wanganui’s match against the Lions in 1971.

The Lions forwards (from left to right: John Taylor, Mervyn Davies, Sandy Carmichael, Willie John McBride, Delme Thomas and John Pullin) win the ball at a lineout and form a protective barrier for Gareth Edwards during the Lions’ demolition of Wellington at Athletic Park. Getty Images

Bruce Hunter can do nothing to stop John Dawes diving over to score against Otago. Getty Images

Sandy Carmichael shows the shocking damage he suffered to his face against Canterbury. John Reason

Sandy Carmichael and Ray McLoughlin prepare to head home. John Reason

Above and right: Ray McLoughlin, compete with Gerald Davies’ hat, John Reason’s binoculars, his own tape recorder and a plastered thumb, spies on the All Blacks’ practice before the first Test at Dunedin. Gordon Brown, meanwhile, watches the training session from the other side of the pitch. John Reason

Willie John McBride addresses the players during a break in play in the first Test. ‘No matter what happens in this game, when it’s over there’ll be no excuses. Either we’ve won or we haven’t. If we haven’t won, we’re not good enough.’

Barry John launches a counter-attack from deep within the Lions’ territory during the first Test. InphoPhotography

Fergie McCormick. After an illustrious Test career, he would finish his time in an All Black jersey having been toyed with mercilessly by Barry John’s near-faultless kicking display.

Colin Meads launches another wave of All Black attack during the first Test, supported by (from left to right) Sid Going, Ian Kirkpatrick, Jazz Muller and Richie Guy.

The Mighty Mouse: Ian McLauchlan charges down Alan Sutherland’s attempted clearance kick. He would dive on the loose ball to score a decisive try in the first Test.

The two sides of a result. A dejected Meads heads for the Carisbrook dressing rooms after the All Blacks’ loss in the first Test.

Doug Smith and Mike Gibson burst into tears in the tunnel after the final whistle

Delme Thomas wins lineout ball against Southland. Auckland Weekly News

All Black prop Jazz Muller flies into a ruck with his studs raised high while playing for Taranaki against the Lions. Auckland Weekly News

Barry John scores against New Zealand Universities, with the crowd stunned into silence by the magic of his running and the Universities’ players lying, helpless, in his wake. Auckland Weekly News

Bob Burgess dives over to score early in the second Test. Auckland Weekly News

Gareth Edwards flicks the ball back to Barry John at Lancaster Park, chased down by Sid Going and Ian Kirkpatrick. InphoPhotography

Gerald Davies brings down Bryan Williams before the All Blacks’ wing had caught the ball, and in so doing concedes a penalty try during the second Test. Photosport NZ

Ian Kirkpatrick bursts away from a ruck on his way to the Lions try line – and into rugby legend. InphoPhotography

Former All Black great, Brian Lochore, puts in a clearance kick after turning out for a ‘one-off comeback match’ for Wairarapa-Bush. Auckland Weekly News

David Duckham bursts away to score a sensational early try against Poverty Bay/East Coast. InphoPhotography

Geoff Evans rumbles over to score against Auckland. Auckland Weekly News

Back in black: Brian Lochore alongside Colin Meads in the third Test in Wellington. Photosport NZ

Gareth Edwards hands off Bob Burgess on his way to creating a try for Barry John in the third Test.

Mike Gibson bursts away to score against Manawatu-Horowhenua.

Bob Hiller stretches out to score against Manawatu-Horowhenua. The Boss added three conversions and three penalty goals to his haul at Palmerston North. Auckland Weekly News

JPR Williams dives over for the Lions’ second try against North Auckland. Ken Going and Bevan Holmes (on the ground) are powerless to stop the Lions’ fullback. Auckland Weekly News

Alistair Biggar dives over the Bay of Plenty line as Miles Spence tries to pull him down. Auckland Weekly News

Gordon Brown goes down after taking a right hook from Peter Whiting at the second line-out of the fourth Test. Whiting looks ready to have another crack should Brown rise to retaliate.

While Brown is off the field receiving treatment, Wayne Cottrell bursts through to score for the All Blacks. Getty Images

Gerald Davies and Bryan Williams compete for a high ball during the fourth Test.

Barry John slots another goal to add to his record-breaking points haul for a Lions tourist.

Gareth Edwards takes a quick tap penalty to break away up field in the fourth Test – it would prove to be the spark that eventually led to Peter Dixon’s try.

Peter Dixon, under a pile of bodies, crosses to score in the fourth Test. ‘I like to remember it,’ he said, ‘as a classic eighty-yard try.’ Auckland Weekly News

Tom Lister dives over to score for the All Blacks to keep the game on a knife-edge.

The right boot that sealed the series. ‘I liked to call it the eighth wonder of the world,’ recalled JPR, modestly.

The players raise their arms in joy – and no little surprise – as JPR Williams fires over his monstrous drop-goal.

The end of the road. Colin Meads says farewell to the Test arena as a player alongside Lions’ skipper John Dawes, manager Doug Smith and coach Carwyn James. Only second-row Gordon Brown would continue playing in the international game after the fourth Test in 1971.

A rugby man to the end: Colin Meads joins the Lions for a beer in their changing room after the fourth Test. Meanwhile, Gareth Edwards and Gerald Davies, far left, contemplate the strange anti-climax of achieving sporting immortality.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In the late summer of 2016, at a book signing at O’Mahony’s on O’Connell Street in Limerick, it was pointed out that it was forty-five years since the great Lions tour of 1971 – and perhaps it was time for a retrospective on that incredible rugby crusade to New Zealand. When Lions Roared is the result.

Over the months that followed that conversation, we rewatched every available piece of footage and read everything we could lay our hands on about the tour, the years leading up to it and the years afterwards. We got in touch with as many Lions, All Blacks and provincial New Zealand players as we could. And every second of it was both a pleasure and a privilege.

We are indebted to our fantastic colleagues in New Zealand, Tony Johnson and Lynn McConnell, for all their work in helping to piece the jigsaw together from the Kiwi side of things, often conducting interviews on our behalf and putting us in touch with former players, as well as sending through a treasure trove of newspaper cuttings and scans from old magazines and books that were produced in New Zealand in the aftermath of the ’71 tour. John Griffiths was able to do much the same from Wales and thanks go to him for all his help with our research.

Thanks also to Elspeth Orwin in the Sir George Grey Special Collections department at Auckland Libraries; the archivists at the National Library of New Zealand; Dave Barton at the British & Irish Lions; and photographers Ans Westra and Peter Bush whose images brought the tour to life for us. Thanks also to Katie Field and Julie Fergusson and everyone involved at Polaris Publishing.

Thank you to Stephen Jones, David Barnes and Nick Cain, who worked with us on Behind the Lions: Playing Rugby for the British & Irish Lions, which provided a strong foundation when we set out to write this book. Furthermore, both John Reason’s The Victorious Lions and Terry McLean’s Lions Rampant were invaluable to our research. They provide a ringside seat to each match on the tour and are brilliantly insightful accounts.

Most importantly, thank you to all the players who so generously gave up their time to speak to us; it was wonderful to be able to relive the great adventure with you. We hope that we have captured the essence of the tour as you remembered it.

Finally, thank you to our loved ones (Lynn, Eilidh and Tom; Julie, Isla and Hector) for putting up with us during the mad months while we wrote this book. Tom would also like to thank the greats of Court Brack, Castleconnell and Rintulla for their love and support.

Tom English & Peter Burns

PROLOGUE

BOY, COULD THEY PLAY

BARRY JOHN was in the bath when the intruder entered his bedroom and made away with the watch which had been given to him by his wife as a departing gift. Barry never heard him, never saw him, and by the time he noticed that the watch was gone, it was too late. It was a moment in history – the one and only occasion the New Zealanders got the better of the King during that storied summer of 1971.

The Lions were in the town of Pukekohe, fifty kilometres south of Auckland, and Carwyn James’ tourists were about to begin their three-month, twenty-four-match trek around New Zealand against some obliging rural fodder: Counties-Thames Valley. The following day, the Lions put twenty-five points on them. For the New Zealand press, it wasn’t enough. If the Lions were any good, they wrote, they’d have scored fifty.

After one game, conclusions were drawn. The All Blacks should beat this lot 4–0 in the series. Anything less would be an affront to the jersey, an insult to the legacy of their former coach, Fred Allen, who had taken charge for sixteen Tests up until 1968 and who, by winning sixteen out of sixteen, had sent a message to the wider world that New Zealand was the greatest rugby nation on earth.

After two games, the clean-sweep conclusion was being tweaked. The Lions had just hammered King Country and, though the local media maintained that 4–0 was still likely, it was no longer an absolute certainty.

On it went. The Lions ran amok against Waikato in Hamilton, a John Bevan hat trick at the heart of the rout. The Maori got heavy in Auckland, but they were seen off, too. At every turn the Lions were told, ‘Wait until you get to Wellington,’ as if the Wellington boys were the ones who would categorically put the visitors back in their box.

When the time came, the Lions beat Wellington 47–9, and all of New Zealand gasped as one. Bevan got four more tries, Mike Gibson got two and Sandy Carmichael, John Taylor and Barry John got one apiece. Nine scores against one of the preeminent provincial sides in the land. The country had never seen anything like it.

‘Onslaught crumbles capital!’ ran the headline in the Dominion the morning after. ‘Athletic Park watched in stunned disbelief as much as admiration,’ the newspaper reported. The bravado of the 4–0 prediction had now been obliterated, replaced with something approaching fear and awe.

When it was all over, months later, the Dominion produced a magazine of the tour, detailing every cough and splutter of what had happened in each city and one-horse town the Lions had gone to. They hailed them as the greatest team that had ever set foot in the land of the long white cloud, better even than the celebrated men who had beaten New Zealand at home not once but twice in 1937 – the Springboks of Danie Craven, Boy Louw and the splendidly named flanker, Ebbo Bastard.

The Dominion’s final reckoning was that Barry John was the greatest number ten, Gareth Edwards was the greatest number nine, Mike Gibson was the greatest centre and JPR Williams was the greatest full-back. The starting point of the New Zealand media in those innocent early days in Pukekohe in late May was that the Lions were going down; the end point, in mid August, was that the Lions were going down all right – in history.

The documenting of the Lions’ greatness went on for page after page, the last headline encapsulating how the rugby nation felt having watched them in full flow. It simply read, ‘Thank you’.

Joe Schmidt: In 1971 I was only about five years old.

Warren Gatland: I must have been nearly eight.

Vern Cotter: I was eleven.

Warren Gatland: You kind of get brainwashed about the All Blacks. You think the All Blacks are the best team in the world. I thought rugby was invented in New Zealand. I didn’t know that anyone else around the world played it. So, when the Lions came to New Zealand in 1971 and won, it had a significant impact on me. That red jersey has had a profound effect on me throughout my whole life.

Joe Schmidt: My memories are a little hazy, but I remember some of the flying players: JPR Williams, Gerald Davies and David Duckham, the guys who got on the end of the ball and just caused havoc; the likes of Mike Gibson and Barry John, who kicked it, ran with it and did a lot of pretty amazing things. Those are the images that I can recall.

Vern Cotter: My whole school was taken to see them play and I remember it clearly because it was my first big game of rugby. It was Bay of Plenty at Domain Park in Tauranga. We all trooped off in the school bus, walked single file down the touchline and sat on the edge of the field. I was so close to the paddock I could hear the thundering of bodies and feel the wind on my face as these players ran past me. Because we were sitting on it, you could feel the ground moving. I was in awe of that day. It wasn’t just a game of rugby, it was a cultural event and one of my biggest memories as a kid.

Sean Fitzpatrick: My first rugby heroes weren’t All Blacks, but members of the 1971 Lions team. Gareth Edwards was my hero. I even bought myself a red jersey so that when my brother and I played in the garden he would be the All Blacks and I would be the Lions.

Joe Schmidt: I grew up in a country where you start playing rugby in bare feet in the backyard as soon as you can get out of your nappies. Rugby is everything in New Zealand. For a group to come over and remain unbeaten through the provinces and then win a Test series is something that is incredibly difficult to do and it’s a measure of the quality of the individuals that were on that team, and also a measure of the camaraderie that they shared, that they were able to accomplish that feat. In these days of science, where everything is tracked and measured and analysed, where you have GPS to see how far players run, how hard they hit and so on, these guys had the number of empty glasses on the table to see how many pints they had drunk. But boy could they play.

Sean Fitzpatrick: JPR Williams, Gerald Davies, David Duckham, Mike Gibson, Barry John, Gareth Edwards, Gordon Brown, Willie John McBride – just thinking of them makes me smile. All the boys of my age loved the Lions and the way they played. Prior to that tour, everyone had tried to kick like Don Clarke, who was a legend as far as we were concerned. You ran up to the ball and hoofed it as hard as you could, as he did. Then along came Barry John and he kicked around the corner. It wasn’t just that it was different – it was that it worked so well. After that, it was farewell to Don.

Graham Henry: The Lions tours of 1959 and 1971 had an intense effect in our household when I was growing up. My father and I used to talk for hours about those teams. The 1971 Lions changed the face of New Zealand rugby. They helped lay the foundations of the All Blacks side that won the 1987 World Cup and that style of counter-attacking play that we’ve seen from All Blacks sides ever since. That was a tour that had a huge impact on how I coached the game. We got beaten by a team who played fifteen-man rugby. They shook the foundations of New Zealand rugby and from the top down things changed.

Steve Hansen: My father was Des Hansen, the coach at Marist rugby club in Auckland from way back. The 1971 Lions had a big influence on my dad’s coaching philosophy and left a big impression on me as a young lad. Dad’s big thing wasn’t about coaching rugby skills, but getting players to think. When he was coaching, most coaches were ‘Do it as I say’ dictators, but Dad challenged us to think ‘Why did that work?’ or ‘How could it work better?’ When I became an All Blacks coach we’d often discuss the game, and Dad wasn’t shy about coming forward with his opinion. He was a massive influence on me. I’ve been lucky in coaching, being associated with other people as well, but the basics definitely come from him. And a lot of his whole view of coaching, which he passed on to me, came from that 1971 Lions tour and the attitudes of Carwyn James and his players. Their influence on New Zealand rugby in the years since can’t be underestimated.

Graham Henry: After 1971, guys like George Simpkin at Waikato and Frank Ryan at Wellington took on the fifteen-man game as well. They took on a lot of the Lions’ backline set-up, the way their centres stood in defence and how they created space for the players on the outside. I took a lot of that on board. The coaching culture in New Zealand changed, from the grassroots upwards. By the mid eighties and going into the 1987 World Cup, New Zealand boasted a generation of outstanding, modern-thinking, quick-witted players.

I wonder if I would have been as successful as I have been, or if I would have become a coach at all, without that tour. Before Carwyn arrived with a host of new ideas, coaching patterns in New Zealand had become sterile. Everyone was doing the same thing, no one dared to be different. The game had moved on. You have to understand, New Zealand is a very young country, and rugby has put our country on the map. This country earned respect from the rest of the world for three things: what we did in two world wars and, to a lesser extent, what we’ve done on the rugby field. So, over time, rugby has become a major part of our national identity. And in 1971, the Lions showed us how to play.

CHAPTER ONE

WE ALL WANTED TO BE CARWYN JAMES

RAIN ROLLED in over the Gwendraeth Valley in the heart of South Wales, a swirling wind sweeping across the field of the village rugby club, with its hand-cut steel goalposts lovingly painted in Cefneithin’s yellow and green colours. It was a late-summer night in 1957 and there was little sound to be heard other than the intermittent thump of leather on leather as rugby ball was struck by boot. Carwyn James raised a hand in signal to a small group of boys who were huddled behind the posts, all shivering with the cold and who immediately punted the balls back to him.

It had become a tradition that, come rain or shine, whenever Carwyn came out to practise his kicking, the boys from the village would stand beneath the posts to collect the balls and kick them back to their hero, the famous fly-half for Llanelli, hoping to impress him with the shape of their spiral punts and to snatch a few words with him at the end. One of them was a small, wispy boy of twelve, with dark hair and a puckish expression. His name was Barry John.

*

Carwyn James was born in the winter of 1929. A thoughtful, shy child, he not only grew up during the height of the Great Depression, but also in something of an unconventional family set-up. His father worked long, hard hours at the Cross Hands Colliery in Cefneithin, while his mother was forced to pour most of her energy into caring for Carwyn’s brother, Dewi, who had contracted diphtheria.

Carwyn’s sister, Gwen, became something of a surrogate mother to him. He was an insular child, but he found creative outlets with a love of poetry and literature, and then through his talent for sport. He excelled at football and cricket, but it was rugby that stole his heart.

Carwyn became captain at Gwendraeth School, winning six caps for Welsh Schools and making his debut for Llanelli while he was still a pupil. Later, he went to Aberystwyth University to study Welsh. He immersed himself in politics, becoming president of the college branch of the Welsh nationalist party, Plaid Cymru. Later still, he became a Welsh language teacher. All the while, he established himself as the fly-half at Llanelli, and a player that could quicken the pulse. At Stradey Park, he would glide and dance and dictate play in the number-ten jersey. In 1958, at the age of twenty-nine, he won a long-overdue first cap for Wales in a 9–3 victory against Australia. It was a result that was celebrated far and wide throughout Wales, but nowhere more wildly than in Cefneithin.

Barry John: Can you imagine what it was like to be a boy from a little village like Cefneithin and to see Carwyn out there playing for Wales? He was the king. The hero. He was everything rolled into one. There were a lot of boys in the village when I was growing up and sport was always a big thing for us – Liverpool, Manchester United and all the rest of it – but rugby was the biggest. And to get one of the blokes from the village playing for Wales – it was unheard of. And then he went and dropped a goal against Australia. It was like Christmas for us all. We all wanted to be Carwyn James.

His parents’ house backed onto the rugby field and he’d go in there to practise his kicking. The road where we lived was on the opposite side and we’d all go out to watch him. We’d be like little disciples, running around and catching the ball and kicking it back to him. We didn’t have to rely on comic books for heroes. We had our own hero.

Carwyn may have been the master of Stradey Park, but he would only play once more for Wales – a 16–6 loss to France in Cardiff in the 1959 Five Nations. It was Carwyn’s misfortune to be born in the same era as Cliff Morgan, one of the finest fly-halves of the twentieth century. ‘I often wondered why I played more times for Wales than Carwyn,’ reflected Morgan. ‘I think it was because I was stronger. My schoolmaster always used to say, “You’ve got to have strength.” He wrote in one school report, “Not very good in class, his biggest asset is his buttocks.” He believed you had to have big buttocks to be able to ride tackles. And Carwyn was naturally slim and elegant and I was squat and rather nasty. I loved playing against him – he always had a smile. He’d always show you the ball as he was running at you, creating space because you had no idea where he was going to put it.’

For Carwyn, Test-level success wasn’t to be, but his influence didn’t end there. It wasn’t just Barry John and his friends in Cefneithin who worshipped him. In Llansaint, a small village that overlooked the Carmarthen Bay, another young boy would play rugby in the streets, pretending to be Carwyn James.

Gerald Davies: Carwyn was my hero. He had this magical quality of being able to accelerate and sidestep, the ball always in two hands – an electrifying thing to see done so cleverly. I loved watching that. He was the first player I ever saw sidestepping, and he always seemed to have time on the ball. He had a huge influence on how I played.

He teased opponents, almost daring them to tackle him, persuading them to go one way when he had made up his mind to go the other. He was a marvellous player, a delicate player, a whippersnapper, a will-o’-the-wisp. The kind of player who would start the game with his shorts white and pristine and would end the game with his shorts white and pristine. Nobody could touch him.

As a child, I’d loiter after Sunday chapel to listen to the village pundits voice their opinions on the game. Arguments always raged and at no time were they fiercer than when it came to who should play outside-half for Wales. Cliff Morgan played twenty-nine times for Wales, Carwyn James only twice, but to every adult man in the village, it should have been the reverse.

Barry John: I was first picked for Llanelli when I was eighteen. I was still at school, yet here I was being asked to play for one of the greatest clubs in the world. When Carwyn finished playing, he came to coach us. He was such a breath of fresh air and his attitude to the game was very similar to my own. I just loved the way he thought about playing. He’d prowl around the changing room before kick-off and would always encourage us to play it as we saw it. ‘Take a risk or two, make a few mistakes,’ he’d say. ‘As long as you are adventurers, I won’t mind.’ His changing room mantra was always, ‘Think, think, think – it’s a thinking man’s game.’

*

After the horrors of the Second World War and the deprivation that stretched on for the years that followed, the generation that rose from the ashes of the conflict began to come together as ambitious young rugby players in the latter years of the 1960s. Many of them were implored by their parents to do anything but follow them into the heavy industries that dominated so many of the rugby heartlands around Britain. From the soul-destroying darkness and danger of life in the mines in South Wales, the middle and north of England and the central belt of Scotland to the long, laborious and perilous work of life in the shipyards of the Clyde and Belfast, life had been hard for many of them. This had, in turn, created hard men.

Gareth Edwards: My father was away for five years during the war and lost a great part of his life to it. He was a talented singer and there were opportunities for him at the end of the war to continue with that as a career, but he came back to the village and he got a job as a miner. People say to me now, ‘Gareth, you’ve got to slow down, you’re doing too much,’ but I often think of my father and the life he led, and of all the opportunities that he missed out on.

He used to get up at four in the morning to be in work at six. He would work his eight-hour shift and somebody might say, ‘Glan, there’s a chance for you to work a doubler,’ and he would take it and carry on. I never appreciated how hard it was until I went underground and visited a mine many years later. You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face. It was a bloody gruesome thing.

Barry John: My father was a coal miner. Every morning at 4.30 a.m. he would rise and get ready to catch the bus to the Great Mountain Colliery at Tumble, just a few miles from our home. He would work relentlessly once he got there, only occasionally breaking for his sandwiches hundreds of yards underground – if the rats hadn’t got to them first. Not only would he come home utterly exhausted and flop into his armchair, but there were times – if he was doing a double shift – when he’d not even see any daylight for ten days at a time. He would go to work in the dark, come home after six in the evening when it was dark, and in the meantime would be working down there in the pitch dark.

The natural role for me, and for anyone growing up in our village, for that matter, was to follow our fathers down the mines. But I promised my father I would never go underground. ‘Barry,’ he would tell me, ‘if you don’t do your homework, you know where you’ll end up, don’t you? Down the mines with me. And believe me, you don’t want to be doing that.’

Gerald Davies: My father was a miner, too. Saturday afternoon’s rugby match was the time for my father to get some of the floating coal dust out of his lungs, to stretch his limbs that had remained cramped and closeted for hours on end in a tiny, dirty black hole. For me, rugby was a recreational leisure activity; for him it was a great escape.

My father spent most of his working life underground. He had to get up very early in the morning, walk a mile and a half down to the railway track and then catch a train to Glynhebog Colliery. There were times during the winter when he literally did not see daylight at all, except for the weekends. As a result, he never wished anything of the kind on me. For the most part, my parents did much to protect me from any awareness of many of the hardships they had suffered. But they never failed to emphasise that if I didn’t stick to my education then I would invariably follow my father down the pits.

Barry John: My school was near the colliery and I’ll never forget the time of the wailing hooter. Our classroom overlooked the pit and I remember looking down and seeing a scene of just utter panic below us. As the hooter wailed, the teachers ran out of the classrooms and into the playground to try to see what was going on. We were running up and down corridors and in the distance we could hear the wailing sirens of the emergency vehicles.

We were like ants, rabbits, rats – just running into one another in blind panic, asking, ‘What is it? What’s happened? Is everyone okay?’ There had been a huge blast down the pit. My father was so shell-shocked by the incident that he didn’t speak for three days.

Mervyn Davies: My father loathed life underground. To him, the call to arms during the war was a godsend, a chance to flee from the pit. He once said the mines would have killed him if he’d stayed there a moment longer – he preferred taking his chance against the Germans. He was shipped out to North Africa with Montgomery’s Eighth, was taken prisoner and bundled off to Germany where he spent his war trapped behind barbed wire. Although in many ways his war could have been much, much worse, it was an ironic fate to befall a man who had joined up because he felt imprisoned in the pit.

My parents made sure I worked hard at school. If I was going to get anywhere in life, if I wanted to avoid a dirty, dangerous future, if I wanted to get well away from the acrid smoke of the smelters’ yard or the blackness of the mine, then I would have to ‘think’ my way out. My father didn’t want either one of his boys toiling away like him.

Ian McLauchlan: I was born in the mining village of Tarbolton in Ayrshire. My father was a miner and a very strong man, but I also worked on the local farms in the summers from the age of thirteen – no shite about how old you were then. My dad had had vague ambitions that I should be a doctor. I wanted to be a teacher. He was happy for me to do anything to avoid that life down the pit.

Willie John McBride: I was brought up in a wee farm in Moneyglass in Antrim and sport was the last thing on our mind. My father died when I was four and we had to work on the farm. I didn’t play rugby until I was seventeen, and the 1940s were tough. We went to school, came home and helped our mother. Sport wasn’t a part of it for a long time. The first athletic thing I ever did at school was pole-vaulting. I was a pole-vaulter. Tall and skinny. I won the Ulster Schools Championship twice. Then I got too heavy and the pole broke and I was enticed out to play this game called rugby. And it turned out I was pretty good at it. Farming makes you tough.

John Pullin: Our family farm is in Aust in Gloucestershire, and I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t working. As Willie John says, farming makes you tough – which was just as well, because playing hooker for Bristol put you in the firing line in some fairly tasty Anglo-Welsh clashes over the years. Our farm is on the banks of the Severn and the view is all of Wales. I made my debut for Bristol against Newport in September 1961 and I was up against Bryn Meredith, the Wales and Lions hooker. It was a hell of an introduction. And we won. After that, I never looked back. I’d work on the farm from dawn until dusk and then run to training. It was hard, but it was good for me. It gave me a base fitness and strength that lasted my entire career.

Barry John: To earn money when I was eighteen, I had a seven-week spell working at the colliery during the summer holidays. I only worked up at the top, cleaning up a couple of huge pipes and giving the guys underground a helping hand by supplying them with tools. Those seven weeks underlined to me why my father was right to get me to do my homework. Suddenly I was up at the crack of dawn and on the same bus with him. I was young, fighting fit, playing a good standard of rugby and had just started a teaching course at Trinity College, Carmarthen. Every single morning I looked around the bus and saw men in their early twenties and thirties with their eyes shut who would suddenly jerk awake coughing, spluttering and wheezing – a legacy of breathing in coal dust every day. Many of them had been at school with me. All I knew at the end of that summer was that my career path would go in another direction. It had to.

CHAPTER TWO

AM I BORING YOU, YOU BIG PRICK?

IN THE autumn of 1967, the rugby machine that was Brian Lochore’s All Blacks toured the northern hemisphere on the back of two years of blistering form. They had won eight of their previous nine Tests, beating the Springboks 3–1 in a four-match series in 1965 and walloping the Lions 4–0 in 1966. Over those nine matches, they had scored twenty-two tries and were, unquestionably, the most feared team on earth and one of the finest in the history of the game.

They were coached by Fred Allen, otherwise known as the Needle for his refusal to tolerate bullshit. He had captained the All Blacks on twenty-one consecutive occasions from 1946 to 1949 and then moved into coaching, guiding Auckland to twenty-four successive defences of the Ranfurly Shield, the most coveted trophy in New Zealand provincial rugby.

Colin Meads: Fred was a dictator. If you let him down, say, socially, you were cast out, you were gone. Other coaches would say, ‘Come on, we need you back in this team. You’ve got to pull your horns in.’ That wasn’t Fred.

Chris Laidlaw: I was an All Black half-back under Fred. Once, shortly before a Test and in the middle of an Allen monologue, Colin Meads let slip a nervous yawn. Allen came at him like a cobra. ‘Am I boring you, Colin?’

Colin Meads: He actually said, ‘Am I boring you, you big prick? There’s a bus leaving in ten minutes if I am.’

Chris Laidlaw: If Allen had Meads in his pocket, it’s not difficult to imagine his effect on the lesser souls of the team.

Colin Meads: Fred often used me as a means of showing the young ones that he had no favourites. He was straight and I liked that. Before he arrived, we used to be pretty dour and forward-orientated. Backs were a necessary evil. Then along came Fred and changed it all. He said, ‘You’re going to change and if you don’t, you’re out.’ He convinced us that there was a better way to play the game. Fred told us what was going to happen: ‘We’re going to run the ball, it’s going to get out to the wings and you big bastards up front are going to get there and there’ll be no taking shortcuts.’ He used to get into us terribly, which was good for us. And we took to his philosophy. It wasn’t hard – we had good players, we were fit.

The All Blacks were a wrecking ball when they had to be and a thing of beauty when they wanted to be. In their squad they had hard-core leaders in Lochore, the captain from Wairarapa, Meads, the great icon from King Country, Kel Tremain, the fearsome openside from Hawke’s Bay, and Ken Gray, the tighthead rock from Wellington. They also had a cavalry of other players who hadn’t yet made their mark, but who would emerge soon enough – Ian Kirkpatrick, the flanker from Canterbury, his teammate, Alister Hopkinson, a prop with a reputation for badness, Jazz Muller, another prop from Taranaki, and Sid Going, a scrum-half from North Auckland.

En route to Europe, they played two matches in Vancouver and Montreal and knocked the spots off British Columbia and Eastern Canada. Then they started taking the Brits to the cleaners. They won three provincial matches in Manchester, Leicester and Bristol before they fetched up at Twickenham and did a number on England, scoring five tries in a 23–11 win. The gulf in class was ridiculous.

They played fifteen matches on their northern hemisphere tour, winning fourteen – including all the Tests – and drawing one, the penultimate match against East Wales at Cardiff Arms Park.

Brian Lochore: Fred indicated right at the beginning of the tour that he wanted a fifteen-man game, which absolutely suited us. It was great rugby to play. Fergie McCormick was a magnificent running full-back.

Ian MacRae: I was a centre. I won seventeen All Black caps between 1966 and 1970 and most of them were with Fergie. He was outstanding. He was the only full-back selected for the tour and was indestructible. No one ever got past him.

Gareth Edwards: I was twenty years old when they came over, and I have to admit that the fables about the past and all the great New Zealand teams completely intimidated me before the game. They began their tour in Manchester, beating the North of England 33–3, and then they rolled over the Midlands and Home Counties, the South of England and then England itself at Twickenham. I sat in the crowd in Swansea as they beat West Wales 21–14 and I remember being amazed when I saw Colin Meads and realised he wasn’t ten feet tall with one eye in the middle of his forehead. He was much smaller than my nightmares had told me – but he was about as good. There is something about the blackness of the New Zealand jersey that sends a shudder through your heart.

Gerald Davies: Ever since the days when my father talked about them, I had held the All Blacks in awe. Any discussion about them was in hushed, almost reverential tones. From the way he talked, they were indestructible. And from the way the 1967 team played, they seemed indestructible. They were the best side I ever played against.

Gareth Edwards: Wales played them on Saturday, 11 November – a horrible day of high winds and pouring rain. The Welsh selectors decided to pick as big a pack of forwards as they could find, and I remember Norman Gale, our captain, prowling around the dressing room like a caged bear before kick-off. There were a load of new caps that day and I was only winning my third cap at that stage, so we were all pretty callow.

I only have fleeting memories of the game. I remember my second pass to Barry – I remember it because Kel Tremain stamped down on my arm afterwards. It was like it had gone through a laundry press – the pain went all up my back, it was horrendous. If the ground hadn’t been so soft he would have broken it. A huge bruise came up on it later, stud marks and all.

I remember getting up and running off in agony, telling myself it was an accident, but I looked at Tremain more carefully at the next lineout. There he was, seventeen stone, playing as a wing forward. He’d had a cortisone injection in order to play so I knew he must be pretty important. He was massive, ears on him like hydrofoils. After going down under a ruck, their other flanker, Graham Williams, rolled over close to me, close enough to talk. He grabbed my shirt and pulled me just underneath him. ‘Get under there, son,’ he said, ‘and keep your head in or you’ll get hurt.’ He was right – the All Blacks ruck was like some giant combine harvester. Bodies were booted around like chaff.

Barry John: You knew that when you played a side like that, if you made a cock-up you were going to get punished. So don’t make cock-ups, make the right decisions. Don’t be overambitious, get your kicks in nicely, get the right weight on them. Do the basics. That’s what you had to do when you played a team of that calibre. It was the end of the year and Cardiff Arms Park was like a paddy field, so I decided to put in little dinks here and there and little grubbers, making them turn on the heavy ground, making it difficult to get back to cover the ball. We were playing well, keeping it steady and tight, but then late on they took a penalty shot at goal and it hung in the air and then fell down short, next to the upright. And one of our new caps, John Jeffrey, made a mess of it and they jumped on it to score a try. And that one mistake knocked the stuffing out of us because with that try we were ten points behind and there was no way we were going to overtake that deficit in the time left. I got a drop goal, but it was too little too late.

Gareth Edwards: I tackled Ian MacRae and cut his eye open with my head. Later, at the dinner, I went over and apologised to him. He said it was okay. The blood was dripping down his dinner suit as he said it.

Fergie McCormick: Fred was especially keen that the All Blacks should beat Wales. I’ll never forget Needle after we beat them. He was out on the ground with mud over his shoes, congratulating the guys.

The All Blacks juggernaut just kept on rolling. They travelled to France to face the Five Nations champions, scoring four tries in a 21–15 win, and beat Scotland at Murrayfield despite Colin Meads being sent off for kicking the ball out of fly-half David Chisholm’s hands.

Sandy Carmichael: I was partly to blame for Meads getting sent off. I kneed him in the gut because he’d been punching one of our guys. He lashed out with a foot and caught Davie.

Fred Allen: To watch him walk off the pitch like that, it just didn’t feel right. To me, Colin Meads was the greatest rugby player ever. They threw away the mould when they made Pinetree.

Brian Lochore: We beat everybody. The only team we didn’t beat was Ireland, and that was because there was an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease and the game was cancelled. A Grand Slam hadn’t been done before and we had a great opportunity to do it. We missed out.

For the two years that Fred Allen was in charge, the All Blacks never lost a match. He looked untouchable in his position, but his reign was to come to a sudden end.

On 15 June 1968, the first Test of the year, between the All Blacks and the Wallabies, was about to be played at the Sydney Cricket Ground. Allen and manager Duncan Ross had agreed to let Alex Veysey, a reporter from the Dominion newspaper in Wellington, gain access to the All Blacks changing room so that he could write about the sights and sounds of a team preparing for battle.

Veysey wrote how Allan had rapped his fist on a table before addressing his players. ‘I’ve approached a lot of games very frightened,’ he said quietly. ‘But I’m terrified by today.’ There was silence in the room. He looked over at Colin Meads. ‘Pinetree, the Australians were using a sack of sawdust for rucking practice yesterday. D’you know what they called it? Piney.’

One by one he went around the team, telling each of them to front up. Finally he came to his captain, Lochore. ‘Brian, I’m relying on you for strength and leadership today and I know you won’t fail us.’ Then he walked from the room, leaving his players in silence.

Sid Going: Fred’s team talks were like being positioned in front of a firing squad, not certain whether the guns are loaded or not. He had you on the edge of your seat. He had an alarmingly accurate memory of previous matches and used to spear you to the wall by recalling your errors. Those tactics might not have worked with all the players, but they inspired me.

Veysey’s report offered a wonderful insight into the inner sanctum of the All Blacks’ changing room, but it was met with icy disapproval by certain members of the New Zealand Rugby Union. At seven the following morning, Duncan Ross was woken by a phone call from Wellington. At the other end of the line was an irate Tom Morrison, the chairman of New Zealand Rugby, who had just read Veysey’s piece in the paper. Morrison felt that Veysey’s presence had betrayed the sacred confidences of the All Blacks environs and should never have been allowed. Ross was instructed to pass on Morrison’s deep displeasure to Allen.

When Ross relayed the message, the coach was furious in his own right. He felt that Morrison should have had the courage to speak to him himself rather than use Ross as an envoy, and he didn’t appreciate being berated like a schoolboy.

Fred Allen: There was nothing in the article about moves or tactics or anything like that. It was about self-belief and confidence,