7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

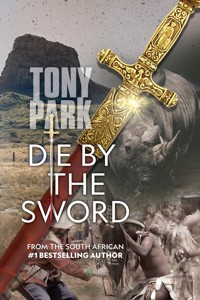

The South African Number 1 Fiction bestseller

Three bodies are found scattered across South Africa. One on the shores of the Indian Ocean, one in a farm invasion in modern KwaZulu-Natal, and one in 1880, in the aftermath of the Anglo-Zulu War.

Detective Sannie van Rensburg and marine biologist and former soldier Adam Kruger are each on the trail of a mystery, while more than a century ago colonial police officer Peter Gregory has a secret mission: to find the lost sword of the great Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

But he’s not the only one who wants it.

From the blood-soaked battlefields of colonial-era Zululand to the modern-day political struggles over land and poaching in South Africa and war in the Middle East, these investigations are on a dangerous collision course.

Because people will kill for a symbol of power.

"It truly is a five-star read." You Magazine, South Africa

Die by the Sword is a dual-timeline contemporay and historical thriller perfect for fans of Wilbur Smith, Ken Follett and David Baldacci.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tony Park was born in 1964 and grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney. He has worked as a newspaper reporter, a press secretary, a PR consultant and a freelance writer. He also served thirty-four years in the Australian Army Reserve, including six months as a public affairs officer in Afghanistan in 2002. He and his wife, Nicola, divide their time between Australia and southern Africa. He is the author of twenty-two other novels about Africa and several biographies.

ALSO BY TONY PARK

Far Horizon

Zambezi

African Sky

Safari

Silent Predator

Ivory

The Delta

African Dawn

Dark Heart

The Prey

The Hunter

An Empty Coast

Red Earth

The Cull

Captive

Scent of Fear

Ghosts of the Past

Last Survivor

Blood Trail

The Pride

Vendetta

The Protector

Part of the Pride, with Kevin Richardson

War Dogs, with Shane Bryant

The Grey Man, with John Curtis

Courage Under Fire, with Daniel Keighran VC

No One Left Behind, with Keith Payne VC

Rhino War, with Maj Gen (Ret) Johan Jooste

Bwana, There’s a Body in the Bath, with Peter Whitehead

CONTENTS

Prologue

1. Bhanga Nek, KwaZulu-Natal, the present

2. After the Anglo-Zulu War, Natal, 1880

3. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

4. Natal, 1880

5. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

6. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

7. Natal, 1880

8. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

9. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

10. Natal, 1880

11. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

12. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

13. Natal, 1880

14. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

15. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

16. Natal, 1880

17. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

18. Zululand, 1880

19. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

20. Zululand, 1880

21. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

22. Zululand, 1880

23. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

24. Zululand, 1880

25. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

26. Zululand, 1880

27. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

28. Zululand, 1880

29. KwaZulu-Natal, the present

Epilogue

Acknowledgements and historical note

DIE BY THE SWORD

TONY PARK

First published by Pan Macmillan Australia in 2025 This edition published in 2025 by Ingwe Publishing

Copyright © Tony Park 2025

www.ingwepublishing.com

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. This publication (or any part of it) may not be reproduced or transmitted, copied, stored, distributed or otherwise made available by any person or entity (including Google, Amazon or similar organisations), in any form (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical) or by any means (photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

Die By The Sword

EPUB: 978-1-922825-37-7

POD: 978-1-922825-36-0

Cover design by Leandra Wicks

Image of Zulu Warrior and British soldier courtesy of Dundee Diehards re-enactment group.

For Nicola

PROLOGUE

THE BATTLE OF ISANDLWANA, ZULULAND, 22 JANUARY 1879

It was his time to die.

For a moment, less than a second, the pounding of blood in Gregory’s ears, the crack of the rifles, the thump of passing bullets, the screams of the wounded and the Zulus’ battle cries were gone.

The acrid scent of burned powder and smoke were like smelling salts as the realisation hit him. The terror was there, making him clench, but it was as if the fear of the unknown had paralysed him, rooting him to this place at the foot of Isandlwana, the Sphinx-like hill behind them. The rock would be here for millennia; his blood would feed the soil like Johnson’s, lying next to him, and the warrior at his feet, his heart run through with Gregory’s own bayonet.

The Zulus were behind them; their fate was sealed. Sub-Inspector Peter Gregory reached into the leather pouch at his belt, drew a round with burned fingers and thumbed it into the breech of the Martini–Henry carbine. He brought the rifle up into his shoulder, and barely needed to take aim. The phalanx of Zulus was almost upon them. He squeezed the trigger and felt the kick in his already bruised shoulder. The smoke obscured the shattered face of the warrior in front of him and the man fell backwards.

Frightened cattle and forlorn humans bellowed behind him. ‘Run! We’re done for.’

To Gregory’s left and right were men he knew. The flotsam and jetsam of the colony, their commander had fondly dubbed them. Old soldiers, miners, rogues and failed farmers – men for whom life was the rolling hills of Natal, a campfire under a sky ablaze with stars, fresh meat sizzling on hot coals, the call of the lion at night. Some in the colony hated the Natal Mounted Police. Gregory had come to love the unit.

‘Look left!’ Jenkins, standing beside him, aimed across Gregory’s body and his rifle boomed, felling a Zulu Peter hadn’t noticed in the melee. ‘That’s a beer you owe me, Peter –’

A warrior’s assegai silenced Jenkins, striking him just under his rib cage. Blood poured from his mouth. Gregory turned, reversed his rifle and drove the butt into the side of the Zulu’s head, knocking him sideways. The man had begun to remove the stabbing spear from Jenkins’ torso, and Gregory reached down and beat the fighter to the shaft, drawing it from his friend’s body and slashing the blade across the staggering enemy’s face. He saw, now, that the man who had killed his friend was young, perhaps in his teens. Gregory drove the spear into his belly. His hands were wet with the blood of friend and foe.

Gregory and the remaining men of the NMP, distinctive in their dark-brown tunics among a sea of British redcoat soldiers, had rallied around Durnford, the only senior officer on this blood-soaked slope who had any idea what he was doing – and now he, too, was doomed to die.

‘Ammunition, here!’ a high-pitched voice called.

Gregory tossed the assegai aside and reached into his pouch for one of his few remaining rounds. He looked up and saw that the call had come from a drummer boy, even younger than the last soul Gregory had taken, half dragging, half carrying a stout box of cartridges. The boy had a bayonet in his hand, and as he set the crate down he tried to get the point of the blade under the lid to lever it open. Gregory was half deaf from the boom of gunfire. He watched on helplessly as another shot caught the drummer boy in the shoulder and knocked him backwards. A policeman stepped in, picked up the bayonet and went to work on the crate.

Steel blades clanged on rifles, men yelled. A British officer with a pistol fired into the oncoming mass of muscled flesh and glinting assegais until the hammer of his weapon clicked on an empty chamber. He was overrun.

Gregory worked the lever under his rifle, sending the empty cartridge flying, then took another from his pouch, loaded, closed the lever, aimed and fired again. His bullet passed through the neck of one warrior and into the chest of another slightly below. It was nothing, though. The wave of men came on, up the slope onto which his comrades had retreated. The policemen, who made up the majority of this, one of several stands against the human tide, were shoulder to shoulder. Gregory looked around and saw the drummer boy lying on the ground, crying.

Two Zulus snatched up the body of one of their own and, taking an arm each and shielding themselves behind him, propelled the corpse onto the bayonets of two redcoats, who fell backwards. One warrior leapt over the tangle of living and dead while the other dispatched the soldiers with downward thrusts of his assegai.

The man who had broken through made for the drummer boy. Gregory scrounged in his pouch, but he had just fired his last round. He turned and strode to the fallen lad, rifle out, and charged at the Zulu who was now raising a spear, aiming at the young bandsman. Gregory ran at him, but the African turned at the last second, perhaps sensing Gregory behind him, and Gregory’s bayonet only just sliced across the front of the man’s torso.

An assegai flashed, cutting through the weave of Gregory’s tunic and into the skin on his chest. Gregory felt the sting as he lurched backwards. He tried to bring his empty rifle up, but the man had closed on him. Gregory felt his weapon crushed against his body as the Zulu tried to bring his spear around his back and into his kidneys. Gregory dropped the rifle and, instead, swung his fist into the side of the Zulu’s head.

Around them the clamour of battle continued its ceaseless din – gunfire, war cries, pleas for mercy, and ruthless swearing as blades sank into flesh. Gregory heard the roar of blood in his ears again, and looked into the eyes of the latest man who was trying to kill him. Dark pupils, bloodshot whites; the other’s sweat stung the inside of Gregory’s nose as their breath mixed. They danced on the battlefield, locked in a terrible embrace. Gregory felt the other man’s strength, the muscles as hard as steel cables, the righteous rage of a man defending his homeland. My home.

In another time he and the man he was fighting could have been neighbours, brothers. And yet Gregory clawed at him and raised his knee into the man’s groin. The man stabbed him – not a good strike, because Gregory held him too close – but Gregory felt the skin behind his left shoulder open nonetheless.

But the man was pushing him, and his rage was greater. Gregory took a step back and then another. He was aware of more shooting, of redcoats and police firing faster; perhaps they had managed to open the box of cartridges the drummer boy had brought up. Maybe there was hope for them, but the heel of Gregory’s right boot hit a rock, made slippery with blood and entrails. He fell.

The fall, compounded by the weight of the Zulu, drove the air from his lungs. He tried to take a breath but felt only pain. He swung his fists again and tried to get a hand in the man’s short hair.

It was his time to die.

The man above him raised his right arm and the blade of the assegai glinted as the sun caught the steel. Gregory put a palm to the man’s bare chest, slippery with sweat. The warrior grinned down at him, safe in the knowledge that in this, the ultimate contest, he had won. The arm came down, as if in slow motion. Gregory closed his eyes.

He was smothered. When he opened his eyes the cheek of the warrior was against his. The man’s body quivered and his chest rattled as the life burst from him. Gregory craned his head to the left and saw the drummer boy, his face streaked with red lines and tears, staring down at him, a bloody bayonet in his right hand.

Gregory rolled the now-dead Zulu off himself and saw that the lad had pierced the man through the back of the heart. The drummer boy’s eyes were wide with the horror of all that he had seen, all that he had done, and his face was white from the loss of blood from his left shoulder. Drained of strength by the effort it had taken to save Gregory, the injured drummer boy dropped to one knee. Gregory got to his feet.

‘No!’ He would not let this boy die.

A horse came towards him, a blue-coated transport officer in the saddle, and Gregory held up his hand to the man.

‘Out of the way, damn you,’ the officer said.

As the officer galloped past, Gregory reached up, grabbed hold of the man’s pistol belt and hauled him from the saddle. The force of the pull nearly wrenched Gregory’s arm from its socket. The startled horse reared up as the falling man landed hard in an eruption of dust.

Spitting dirt, the officer tried to stand. ‘Damn your eyes, man.’

Gregory snatched up his Martini–Henry and, even though it was empty, aimed it one-handed at the fallen man’s head. ‘Help me put the boy on the horse or you die, now.’

The man wiped the back of his hand across a face smeared with dirt from his fall. Gregory put down his weapon and started to lift the boy.

‘Do it yourself, man. And get away while you can, but be warned, I’ll have you charged for insubordination if you survive this bloody mess. The Zulus are behind the hill now. We’re outnumbered, surrounded, done for. It’s every man for himself.’

The officer was right about the Zulus. The British were being out-manoeuvered by their enemy’s simple, yet masterful strategy, based on the anatomy of a bull. The most seasoned warriors in the centre of the formation, the ‘chest’ of the bull, were hammering at the redcoat line, while the ‘horns’, regiments on the left and right of the advance made up of fleet-footed younger men, had pushed out and around in order to encircle their foe.

The drummer boy was barely conscious. The transport officer swung back up into his saddle.

‘Wait.’ Gregory coughed from the dust and smoke. The transport officer looked down at him. ‘If you leave without this boy I’ll shoot you in the back.’

The battle raged around him, pressing in closer. Gregory feared he would have to drop the wounded drummer – he was a teenage lad, no mere child; he was too heavy. The officer looked like he might risk taking a bullet from Gregory.

‘Let me help,’ a deep voice said.

Gregory looked around, saw a Zulu and for a moment thought he was dead. Then he saw the man’s tunic; he was a member of the Natal Native Horse and he had just dismounted. The other man took one of the drummer’s arms and together they were able to lift him up and over the rump of the transport officer’s horse. Gregory slapped the horse and it, and its rider and young passenger, galloped away.

Every man for himself. Gregory spat his disgust at the words into the dust and rock. He looked to the diminishing knot of police and redcoats protecting Colonel Durnford, and the Zulus massing for the final attack.

‘Come with me, Nkosi,’ the African horseman who had helped him said. Gregory recognised the man now – he’d seen him fighting and killing in the donga alongside Durnford, and the colonel had ordered this man and his comrades to retreat, yet here he was. He stood eye to eye with Gregory, dressed in a khaki tunic and boots, an assegai in his hand and two more throwing spears up-ended in a pannier strapped to his saddle.

Gregory shook his head. ‘Go.’ He knelt by the body of a redcoat, shot through the forehead, and scrounged the last three cartridges from one of the man’s pouches and two fallen rounds from the dirt. He glanced up at the African soldier, now back in his saddle, but hesitating. For the briefest of moments, Gregory was tempted to flee, but the revulsion he’d felt at the transport officer’s words brought him back to the unassailable truth. His place, his fate, was with those men around Durnford, firing and loading, clubbing and stabbing with their rifles. He had nothing in life except his honour and the uniform he wore.

He glanced over and saw the back of the fleeing transport officer and his horse’s rear end disappear over a rise, downhill towards the river. At least the drummer boy was safe.

Then there was a yell behind them and a young Zulu, in the vanguard of the encircling right horn of the army, leapt over a boulder and sprinted towards them, spear outstretched.

The horseman wheeled his mount around so he was almost between the oncoming warrior and Gregory, who worked the lever of his Martini–Henry, slid a cartridge into the breech and locked the rifle closed. He raised the weapon to his shoulder, aimed around the brave man defending him and squeezed the trigger.

Click.

‘Hell.’ Gregory worked the lever to clear the misfire and saw the grit and dirt ejected along with the filthy cartridge that had jammed. If the native horseman galloped away now – as he should, he could save himself – then Gregory would have to take on this latest fellow with his bayonet. His throat was parched, his limbs heavy.

The horseman reached behind him, dropped his assegai and picked up a longer throwing spear. As the warrior ran past him, the horseman drew back his arm and hurled the spear downwards, into the back of the oncoming Zulu. The man fell at Gregory’s feet.

‘Come with me, Nkosi,’ the horseman repeated, more forcefully this time.

Gregory shook his head. ‘No, thank you. I’ll stay and fight –’

His world went black.

It was his time to die.

BHANGA NEK, KWAZULU-NATAL, THE PRESENT

The full moon broke free of the layer of cloud hugging the horizon and cast a pillar of silver on the Indian Ocean as it climbed.

It was beautiful, and should have been perfect, but Adam Kruger frowned.

He strode across the empty white sands of the beach at Bhanga Nek, eyes scanning left and right, just as he had done during his time in the army, on patrol in Angola. Tonight, he looked not for danger but for life. In rugby shorts, a Rip Curl T-shirt and bare feet he was neither hot nor cold. He was at one with his environment, as much a part of it as the turtles he searched for.

Adam was at peace, yet still he felt his right arm bend at the elbow as he walked while his left arm remained straight. It was the same as when he and Sannie had hiked in the Drakensberg three weeks earlier – the muscle memory kicked in whenever he walked in the bush or somewhere quiet and remote, like the beach. As his eyes scanned the terrain for threats, so, too, did his hands imagine they were holding a gun.

He shook his head and his arms as he walked to try and clear the stupid notion. The canvas satchel slung across his body bounced on his back with every step; Adam heard a distant rumble and looked to the horizon again. The cloud was a front, and he knew from the forecast it was heading towards the coast, and his turtles.

Adam plucked at his T-shirt as he walked on, thinking, cursing, sweating. Even at nine o’clock at night the humidity was still high. He’d done one up-and-back survey already, covering eight kilometres. The beach curved in a gentle crescent as Adam approached the northern end for the second time that evening. Here the strip of sand was at its narrowest and rose steeply to a high dune. Behind that was a belt of thick vegetation, a tangled jungle of lala palms, strelitzias and umdoni trees.

The impending storm worried him and added to feelings of unease that were not related to turtle hatchings. He and Sannie had argued, again, on the phone. He should call her.

But phone signal was patchy here. It was only when he was in the Ezemvelo KZN research buildings, in the KwaZulu-Natal national park authority’s encampment at the southern end of Bhanga Nek, and had wi-fi access, that he could be reasonably sure of being able to contact her.

‘Yes, Adam, I hear that you want to stay to help these new students, but you said yourself last week that your work there was finished for the season,’ Sannie had said to him the last time they had spoken.

He should have been in his bakkie, on his way back to Pennington – to Sannie and the house they had shared for over a year.

Adam had wanted to call her again today, but the wi-fi had been down. He wanted to tell her about the unusually high tides and the nest of eggs that had been washed away during the last storm. All the indications were that the front that was heading their way – he glanced to the right again as he caught a far-off flash of lightning – would be even worse.

Adam saw tracks. ‘Shit.’

He quickened his pace and came to the place where the female leatherback had just laid her clutch of eggs. It must have happened while he had been trudging down the other end of the beach. Adam kicked himself. If he’d looked back over his shoulder, he might have seen the turtle emerging from the distinct riptide off to his right, but he’d been preoccupied thinking about Sannie.

Adam stood there, hands on hips, fuming. The indentations of her flippers were stark, accusatory in the now-bright moonlight, but the thunder was louder to the east. He looked over and saw the cloud rising up towards the moon. A stiff breeze chilled the sweat on the back of his T-shirt.

The turtle had laid her eggs in the same place she had probably chosen for the last twenty years, but it could not have been a worse location. This was the narrowest point of the beach and Adam could see that this area had been inundated and carved away by the last run of bad weather. It was no secret that the storms were becoming more frequent and violent along the coast – the Easter before Adam had returned to South Africa from Australia a few years earlier, more than three hundred people had been killed in devastating storms that had hit Durban and the KZN coastline.

Adam looked around him. From the direction of the research camp to the south, he saw two people approaching, walking on the hard-packed wet sand near the water’s edge. He checked his watch. The tide was coming in. He recognised them and waved to them; it was Jenny and Thabo. Perhaps sensing his urgency, they started to jog.

Adam dropped to his knees, shrugged the satchel off his shoulder and started digging in the sand at the place where the sea turtle had stopped and made her nest. He was scooping sand into a pile when the two research students arrived.

‘What’s happening, Prof?’ Thabo Radebe, in board shorts and a long-sleeved bush shirt, was panting, hands on his knees. He was a heavyset young man.

Adam gestured over his shoulder with a flick of his head. ‘Storm’s coming, and when she hits, the waves will wash this nest away.’

‘You’re going to relocate the eggs.’ Jenny Ellis was bent at the waist, looking down into the hole he was excavating. Her long, straight red hair fell like a curtain around her face. She brushed a strand aside. She wore cut-off jean shorts and a white tank top.

Adam looked up at her. ‘Yes. But we haven’t got much time. The tide won’t quite reach here, but this storm’s going to bring some hectic waves.’ A crash of thunder and a bolt of lightning that hit the ocean punctuated Adam’s words.

‘We need a box, and a blanket maybe,’ Jenny said.

Adam nodded. ‘Exactly. Can one of you please go back to the camp and get what we need?’

Thabo cast a look down the long beach.

‘Thabo, you stay here and help the prof,’ Jenny said. She reached into a pocket and pulled out an elastic, then drew her hair back into a ponytail. ‘I’ll run back to camp and fetch the Polaris. ‘OK, Prof?’

‘Yes,’ Adam said. ‘Quick as you can, please, J.’

She nodded and jogged off. At fifty-five, Adam was probably the fittest of the three of them, although he had seen Jenny running on the beach.

Thabo lowered himself down next to Adam.

‘Careful as you dig, Thabo. We should be getting near the eggs. They’ll be about –’

‘– fifty to sixty centimetres below the surface.’ Thabo scooped at the sand, but Adam could see he was taking care with his big hands.

‘Well done, Thabo.’

Thabo nodded. ‘What are our chances of saving them, Prof?’

Adam was still getting used to being called ‘Professor’. He liked it. How could he explain to Sannie that he was happy to spend a few extra days helping these students, even if they weren’t technically his responsibility, just because he appreciated their interest in science, turtles, and the environment? And how could he explain why he would sometimes rather be here on the beach alone in his thoughts in the middle of the night than home in bed with her? It was easier to think about turtles than relationships.

‘I’ve done it before, Thabo, and we saved most of them. Some people say we shouldn’t try and artificially incubate the eggs, but there are sometimes good reasons – like now, if we know the nest is going to be wiped out in a storm.’

‘And there’s an argument that with rising temperatures, we need to move some eggs to a cooler environment to ensure a viable population of males remains in the wild.’

‘Yes.’ Thabo was right – the temperature of the sand in which turtle eggs were laid determined whether the hatchlings were male or female, and with coastal temperatures rising worldwide, more females than males were being born. ‘Man’s created this problem, so we’re within our ethical rights to step in and try to fix it.’

Adam opened his satchel and took out a black Sharpie permanent marker.

‘I’m getting to the eggs, Prof.’ Thabo had slowed his digging and was now brushing grains of sand from the tops of the first visible white eggs. Each was the size of a ping pong ball, and there would be about a hundred in the nest. Extracting and relocating them would be a time-consuming job.

‘These are leatherback eggs,’ Adam said, ‘which makes it even more important that we save them.’ Both loggerhead and leatherback turtles used Bhanga Nek for nesting, but the leatherbacks were rarer and more threatened. While adult loggerheads stayed in the waters offshore from where they were born, leatherbacks roamed the world’s oceans and, as such, were at far greater risk of being caught and killed as unwanted ‘by-catch’ by commercial fishermen.

They both turned at the sound of an engine, revving hard from the south. ‘It’s Jenny,’ Adam said. ‘She must have sprinted.’

Jenny roared along the shore on the Polaris, their four-wheel drive all-terrain vehicle, and pulled up just short of where they were digging. She hopped off, bringing three boxes with her. ‘I hooked up the trailer as well,’ she said.

‘Good thinking,’ Adam said. He took the lid off the Sharpie and Thabo moved over to make room for him. Adam knelt down and started carefully marking black dots on the top of each egg. ‘Do you know why we do this?’

Jenny answered. ‘Unlike a chicken, a turtle can’t turn its eggs over, so the hatchlings develop by attaching themselves to the inside of the eggshell, so they can draw nutrients from it, and a pool of liquid forms above them, inside the egg, at the top. If you were to take an egg out of the nest now and tip it over, the turtle would drown in the fluid, inside the egg.’

‘Correct.’ As he marked each egg, Adam carefully removed it and handed it to either Thabo or Jenny who in turn placed it on a beach towel that lined each of the boxes, with the black dot from Adam’s marker uppermost. Adam took a temperature sensor from his satchel – it was the size and shape of a ping pong ball, just like one of the eggs. He paused to move a few of the eggs and place the sensor in amongst them. He went back to handing the embryonic turtles to the research students and when they had extracted all the eggs and filled the three boxes, he removed the egg-shaped thermometer. He noted the temperature – they would keep the eggs at that same level.

They loaded the boxes in the trailer and Adam told Thabo to get in the front seat of the Polaris next to Jenny. ‘I’ll walk.’

‘You sure, Professor?’ Thabo said.

Adam grinned. ‘I’m not that old – yet. Besides, I want to walk alongside you to keep an eye on these eggs. Drive on slowly, Jenny. No rush.’

Jenny nodded, got in, and started the engine. They moved off at a brisk walking pace – Adam’s default setting – sticking to the firm sand just above the rising tide.

As he walked, Adam felt spots of rain on his face. The sky darkened as the clouds consumed the moon. The wind picked up and Adam shivered a little. The thunder sounded like a creeping mortar barrage and another lightning strike made him catch his breath. Fortunately, the students were talking to each other and not looking back at him.

Jenny was still attuned to her surroundings, though. ‘Professor?’

Adam looked up from the trailer full of turtle eggs. Jenny was pointing down the beach.

‘Is that a . . . turtle?’ Thabo said. He had to raise his voice over the roar of the surf. The waves were growing with each set and Adam was now being pelted by fat raindrops. Thabo and Jenny had some shelter from the roof over the ATV’s small cab.

Adam looked to where they were pointing and Jenny slowed the Polaris to a crawl.

‘What the hell is that?’ Jenny took one hand off the Polaris’s steering wheel and put it over her mouth. ‘Oh, no! Is that a body?’

‘Keep driving, Jenny,’ Adam said. She was right. ‘Thabo, get out, walk alongside the trailer and keep an eye on the eggs.’

Jenny stopped the vehicle and Thabo alighted. ‘We’ll come with you. We can help you.’

Adam moved to her side of the ATV and blocked her from getting out. ‘Jenny, you’re young – both of you. I hope that in your life you don’t have to witness a violent death, but you have to believe me, when you do, you can’t un-see it, ever.’

She looked into his eyes. ‘You were in the army, in the war, in the old days, right?’ She pointed to the parachute emblem tattoo on his arm.

‘Yes, I was a Parabat. In Angola.’

Thabo looked past him, to the dark inanimate object that had washed up on the shore. The waves were making it roll. Thabo swallowed hard. ‘Let’s get the eggs back to camp, Jenny.’

Adam clapped Thabo on the arm. ‘Good call, bru. Let’s salvage some life. This weather is turning to kak. Get those eggs indoors.’

Thabo nodded. Jenny pressed the starter.

‘I’ll be back, just now,’ Adam said. ‘Call the police when you get to the camp, Jenny.’

‘Will do, Professor.’

The rain was stinging him as he went to the water’s edge. The surf receded, though each new set of waves was bigger than the last, the whitecaps whipped to a frenzy by the onshore wind. The details were revealed to him.

It was a man, dark-skinned but not African. He wore jeans, but the right leg was gone below the knee. The head was a mess, half missing, which would make identification difficult. The shirt had been ripped from the body, and the torso had been opened by a shark. Adam stood over the remains. No heart.

Adam walked into the water until it was over his ankles, grabbed an arm and the good leg, and dragged the body up onto drier sand. He searched the trouser pockets – nothing. The man wore a diving watch, mid-range. The foot that remained was bare. The jeans puzzled him. This was no hapless fisherman, nor a local who’d gone for a swim after too much to drink.

Adam straightened again and looked down the beach. Jenny and Thabo were almost at the camp. Adam would walk down and bring the Polaris back, along with a plastic tarpaulin in which to wrap the body. The police would need to inspect it, but as the dead man had come from the sea – there were no tracks on the beach to suggest otherwise – there was no crime scene to contain. He’d call Sannie, as well, to ask her if there was anything else he should be doing until the local police arrived – and that could take hours.

Adam glanced down at the man again and closed his eyes. He breathed in the smell of the sea, listened to the waves crashing and concentrated on the rain pelting his skin, but he could not stay in the moment, as his shrink would have suggested. He was in Angola again, the crump of mortars replacing the thunder, the stench of death and cordite dispelling the freshness of the ocean and of peace.

He turned away, walked a few paces, sucking in the night air and the rain that cascaded off his nose and onto his lips and plastered his shirt and shorts to his lean, hard body. Adam put his hands in his close-cropped silver-blond hair and tried to cram the memories back into his head.

Turning towards the sea, he noticed something bobbing, half submerged and tumbling in the waves. He waded into the water again and reached for the object. It was squarish, and bulky from being swaddled in several layers of plastic bubble wrap, which had kept it afloat.

Adam picked up the package and returned to the dry sand, giving the body a wide berth as he tried not to look at it. The rain eased, then stopped. The clouds parted, like a chink in a nosey neighbour’s curtains, and the effect was to send a beam of moonlight onto the troubled ocean and illuminate the object in his hands.

It was heavy – maybe three or four kilograms. He unwrapped it with wet fingers made soft by the rain, and fumbled with the sticky tape. Someone had really wanted this thing to stay dry.

The plastic wrapping snapped in the wind as he rolled the object over in his hands. He had uncovered a casing of some kind and it looked old. It was made of a metal – maybe brass or copper – which gleamed in the moonlight. When he had finally freed it he thought it looked like a prop from some kind of ancient history or fantasy film. It was like a mini treasure chest, inlaid with what looked like decorative metalwork and what were probably fake or semi-precious stones.

Adam paused to bundle the discarded bubblewrap and stood on it so that it didn’t blow into the ocean. Looking back at the object he found a latch, which he opened, revealing a book inside the small chest. It looked like a medieval Bible, and when he opened the stiff, worn leather cover he saw words inside on yellowed parchment. They were like a monk’s calligraphy, but they were not in English or Latin. They were in Arabic.

He glanced again at the body. Did the plastic-wrapped book, perhaps an antique copy of the Koran, belong to him?

AFTER THE ANGLO-ZULU WAR, NATAL, 1880

There was a knock at the door. ‘Compliments of Hellfire Jack, Mister Gregory, sir,’ the voice called from outside. ‘You’ve an appointment with a dead body and a journalist.’

Peter Gregory opened one eye in the dim, two-room thatched farmhouse that smelled of woodsmoke, mould and woman. Preeti, Harpreet Naidoo, who now wished to be known as Grace, stirred beside him, warm under the sheet and blanket.

‘Go away, Phillips,’ Gregory croaked. ‘It’s Sunday, a day of prayer and rest.’

Sergeant Gavin Phillips brayed. ‘Very good, sir. But the major was most adamant. Your presence is requested now, sir. And might I come in? It really is raining quite heavily outside.’

Phillips was twenty, seventeen years younger than Gregory. In the British Army he would have been a second lieutenant, a wet-behind-the-ears whelp in his first command, but he’d been brought up in the colony, the son of a wealthy cane farmer, so had joined the local force. Phillips had enlisted in the Mounted Police with the hope of seeing action, but had been too late – the war had finished before he could fire a shot in anger. However, so many police had been killed at Isandlwana that Phillips had been propelled up the ranks from constable to sergeant in quick time.

‘No.’ Gregory ran a hand through his unwashed, thick, dark mane, which hung down to his collar.

Black eyes framed by a matching curtain of silky fringe peeked over the top of the blanket and blinked at him. Gregory winked back.

Phillips thumped on the door. ‘Sir, the major told me I must not return to camp without you, or he’ll have my guts.’

Gregory reached for his pocket watch on the sawn-off stump that served as a bedside table. The back of his hand brushed the empty square-faced gin bottle, which toppled and landed on the slate-hard floor of polished and hardened cow dung with a crash. Grace started and pulled the covers back over her head.

He swung his legs over the side of the timber-and-rope bed and pulled on his cavalry breeches and boots. As he stood, he hitched the braces over the shoulders of his collarless, grimy undershirt. Thunder rumbled, like Chelmsford’s four-pounders firing in the distance, and a crack of lightning sounded like a bursting shell.

Gregory lifted the wooden latch from its stay and opened the door a fraction. Phillips paused, fist up, ready for another knock. Rain streamed from his off-white pith helmet onto the thick corduroy of his dark brown Natal Mounted Police uniform tunic. Gregory caught a whiff of horse and sweat.

‘I’ll be out in fifteen minutes, Phillips. Wait in the barn. Ask Samuel to –’

‘I’ve already told the bloody –’

Gregory held up a finger. ‘Please ask Constable Khumalo to saddle my horse.’

‘I’ve already done so, sir. And if you don’t mind me saying so, that . . . man, Khumalo, has something of a superior attitude, unbecoming in a native.’

Gregory reached for his own police tunic, hanging on a hook. ‘That’s because he’s a prince, Phillips, a member of a Zulu royal family. Best not to forget it. If you were back home in London, he’d have you cashiered and horsewhipped for insubordination. I’ll be out directly.’

Gregory waited long enough to see Phillips trudging through the mud to the barn before closing and latching the door again. He tossed the uniform jacket on the bed, then went to the hearth and prodded the fire’s near-dead embers with the tip of a rusted Martini–Henry bayonet.

It was May and the Natal Midlands was colder in the approaching winter than any of Gregory’s estranged family back in England could have imagined. The unseasonal late rain, some of which was finding its way through the thatch roof, just made it more miserable. Gregory laid a taper on the glowing coals until a flame appeared and used it to light a thin cigar from a tin box on the simple brick mantelpiece. He coughed.

Grace emerged again and wiggled up the mattress until her back was against the bedhead. Though she held the sheet up, Gregory saw the shadow of one dark, wayward nipple peeking around a fold. He felt a tightening in his lower belly.

She frowned. ‘I’m not inclined to agree with the current body of medical evidence that smoking is conducive to good health and an improved respiration.’

‘Preeti . . .’

She frowned. ‘Grace.’

‘I liked your Indian name better. Now that you’re a God-fearing, baptised Christian lady, you should be repenting for what we did an hour ago, not lecturing me about smoking.’

She drew the sheet up to cover her face completely. ‘You are a perfectly horrible man, Captain Peter Gregory. I shall pray for your soul.’ Grace liked to refer to him by his former army rank, captain, which he’d held before joining the police, as she thought it sounded more important than his police position as a sub-inspector. Still in her twenties, Grace was big on social standing. She blinked at him again, the bedclothes now revealing only her eyes. ‘Do you have to go?’ she purred.

He put his cigar in an ashtray made from a giraffe’s vertebra he’d scavenged from the remains of a lion kill on the banks of the Umfolozi River, shrugged on his tunic and buttoned it up. ‘When Hellfire Jack Dartnell calls, one doesn’t say no.’ Gregory took his pistol belt from the back of the chair and buckled it on. ‘Besides, no one else would employ me.’

Gregory drew his revolver, thumbed back the hammer and spun the chamber. Satisfied that it was clean, he slid it into its holster.

‘You had the night terrors again, Peter,’ Grace said.

He looked in her direction, but let his eyes rest on the whitewashed wall above her head. His mind projected a magic lantern image of a field of naked bodies, each sliced from sternum to groin, the viscera spilling out. Fires flickered at the corners of the scene; a single gunshot silenced a horse’s dying whinnies. He screwed his eyes closed. Gregory remembered, now, waking in the small hours of the morning, screaming.

‘Peter . . .’

He opened his eyes and manufactured a smile. ‘Probably the tinned fish we had for supper.’

Grace shook her head. ‘There is no need to make light of it. Your soul is injured, but your pain may come from one of your past lives.’

Gregory gave a snort. ‘I doubt your new friend the Baptist pastor believes in your Hindu notion of reincarnation, Preeti.’

‘Grace . . .’

He put his spike-topped pith helmet on and adjusted the chinstrap. ‘I don’t believe in past lives.’

‘You were troubled before . . . when I first met you, Peter. Karma teaches us that we can change our situation, our present life, no matter what grievances we suffered in the last.’

Gregory picked up his cigar and took another drag of it, the tobacco enlivening him even as he coughed again. He stubbed it out. Gregory looked at Grace, in bed, and revelled in some impure thoughts for a few moments. He sighed. ‘I must away.’

She lowered the sheet a little and gave him a smile to accompany the improved view. ‘You won’t reconsider?’

Unless he drowned himself in gin, she was the only thing that could currently make him forget the horrors of the last twelve months. It felt like a curse that even in her arms, in their warm bed, the terror bubbled up inside him like a cancerous growth, eating him from within.

It was a wrench, but he also knew that doing something, even riding in the rain, helped. ‘Phillips will be back looking for me soon. Best he finds you in your maid’s clothes, dusting.’

She lowered her eyes with the exaggerated slowness of a music hall actress. ‘Yes . . . sir.’

He almost ripped his jacket off again, but instead he opened the door and walked out into the rain. Grace was on the right path in her life, at last. She didn’t need him and his melancholy dragging her down or ruining her reputation when she was making a very good effort at salvaging it.

Grace had been grateful of his offer of refuge on his farm, but she had also, in a polite and businesslike manner, made it clear to him that despite whatever attraction they felt for each other, she did not intend to remain there.

‘I escaped from life as an indentured worker on a farm, and I have no intention of spending the rest of my days mucking out stables or milking cows,’ she had told him, only half in jest. ‘For goodness’ sake, Peter, you can’t even afford labourers.’

Her words had stung, but they were true. He was living off his police wage, and, lately, supporting her as well. Part of his problem, he knew, was that as hard as he tried, he could not wash the blood from his memory, nor the stain of guilt from his soul. Unless he was out riding, in search of some criminal, he found it hard to even get out of bed, let alone work the farm.

Grace had also made no secret of her designs on the Baptist pastor. ‘He’s handsome, and I think he likes me,’ she had said. It was frank, casual comments like this that let him know she would soon be on her way. It was probably for the best.

‘Captain.’ Samuel led their horses from the stable as Gregory approached. The rain had eased to drizzle. Phillips came out, his hands wrapped around a tin mug of steaming tea.

‘Sawubona, Your Highness,’ Gregory said.

Samuel smiled. ‘Sergeant Phillips says we have work to do.’

‘That we do.’ Gregory put a foot in Bullet’s stirrup and hoisted himself up into the saddle on the black stallion’s back. He slid his Martini–Henry into the rifle bucket. ‘Come along, Phillips.’

Samuel was in the saddle and closing on Gregory before the young sergeant was even mounted.

It was two hours’ ride on muddy tracks that cleaved Natal’s emerald-green hills like freshly puckered scars until they reached the mix of ramshackle thatch-roofed huts, timber houses and brick edifices of the colonial capital, Pietermaritzburg.

The air hung heavy with damp, and when the sun did make the effort to cut through the clouds it made the thick wool of their uniforms and the horses’ coats steam in the creeping warmth. It was still preferable to the coast, where Grace hailed from, where the Indian labourers sweated in the oppressive heat and humidity while they hacked at the sugar cane that lined the farmers’ pockets and fuelled the engine of empire.

The war against the Zulus had brought more building, more people, more roads, more colonists, more soldiers and more sin, and while the people of heaven, as the Zulus called themselves, were defeated, more than one man and woman on the roadside cast a sideways glance at Samuel. Those who did could not hold his fierce glare for long; he might have worn white man’s clothes, but with his straight-backed bearing, spears and rifle he was the very essence of a warrior.

Samuel stayed outside to mind the horses when they arrived at the imposing, two-storey brick headquarters of the Natal Mounted Police. A uniformed sergeant led Gregory and Phillips inside and an elderly Zulu woman trailed them along the polished wood-floored hallway, mopping the water and mud they left in their wake.

‘Major Dartnell will see you now, Sub-Inspector Gregory,’ the sergeant said when they reached the commanding officer’s door.

‘Right, well.’ Phillips shifted his weight from one foot to the other, waiting to see if he would be invited in as well. There were no further instructions. ‘I’ll see you anon, then.’

Gregory nodded and knocked.

‘Come.’

He opened the door, saluted, and took off his hat. Dartnell sat behind a large mahogany desk; the cloud-dimmed light from outside was supplemented by an oil lamp that burned hot and hazy on the major’s desk. He looked up from his writings and ran the thumb and forefinger of his right hand down the length of his short, pointed beard.

‘Gregory.’

‘Sir.’ Gregory took a seat.

Dartnell was thinning on top, but he was perhaps only a year or two older than Gregory. His eyes fixed on Gregory like he was prey. Hellfire Jack had earned the respect of his men not only through his straightforward manner and loyalty to them, but because of his history of service. During the Indian Rebellion he’d been recommended for a Victoria Cross after being first up the ladder to storm an enemy fort, and he’d later served in Bhutan, and in the Zulu War. Dartnell put his elbows on his blotter and leaned forward.

‘Are you clear-headed, Gregory?’

Gregory was taken aback, but casually covered his mouth while pretending to stroke his moustache. ‘I’ve not been drinking this morning, if that’s what you mean, sir.’

‘No. That is not what I mean, Gregory. Some men are afflicted by their experiences on the battlefield. A malaise settles upon them and they are unable to shake it off. They withdraw from polite society . . . take refuge in one improper substance or activity or another.’

‘I am in good health, sir.’

The major looked him up and down and snorted. ‘If your mind still works, I have a task for you. I recall how you brought that chap Blundell to justice.’

Gregory nodded. ‘Said his wife had shot herself in the head using her right hand, when some simple enquiries revealed she was left-handed. He was a gambler with outstanding debts and a mistress.’

‘Hmmm. Not the most difficult of cases, but you saw it through to the end, and the fellow admitted his crime.’

‘Yes, sir,’ Gregory said, wondering what the back-handed compliment was meant to achieve.

‘There’s been another murder,’ Dartnell said. ‘A former army officer, killed and slit open, in the manner of the Zulus.’ The major picked up a pen, dipped it in ink and began scratching on a piece of paper. ‘This is the name of the deceased, and his farm, on the road to Dundee.’

‘Yes, sir.’

Dartnell stopped writing and looked up at him. ‘Some local farmers are up in arms, as it would appear to be the work of Zulu renegades.’

‘I wasn’t aware that we’d had any problems with the Zulu since their defeat last year, sir,’ Gregory said, ‘and certainly not here on the Natal side of the border with Zululand.’

The major slid the piece of paper across the desk and Gregory took it. ‘We haven’t, which is why I’m sending you to investigate the killing.’

Gregory glanced at the note. He knew the rough location of the farm. He looked up at Dartnell. ‘Phillips said something about a journalist, sir?’

‘Suspected journalist.’ Dartnell shuffled through a sheaf of papers on his desk until he found the one he was looking for. He consulted it. ‘But, yes. A woman and an American to boot.’ He grimaced and looked up from the sheet, raising his eyebrows. ‘A titled woman, Lady Beecham, one Teresa O’Kane. She is quite the independent traveller, now being estranged from her former husband, Lord Beecham, and claims to be a close acquaintance of the Empress Eugénie.’

It took Gregory a moment to recall something he’d read in the Natal Witness. ‘The mother of the late Prince Imperial of France, sir? Is she not on her way to the colony, sir?’

‘Here already.’ Dartnell’s chest swelled as he drew a deep breath, frowned and nodded. ‘Her Majesty has come to commemorate the first anniversary of Prince Louis’s death, on the first of June, just around the corner. The empress has embarked on a pilgrimage to retrace her son’s footsteps and to be present for the unveiling of a new memorial at the site of his death.’

Gregory nodded. Just over a year ago all their lives had changed. Had it been a year already? If one event had eclipsed the undying shame of thirteen hundred British, colonial and native troops being overrun and slain at that damned rock, Isandlwana, it had been the death in a small skirmish of a single Frenchman – the great-nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte himself in an unnamed donga, a dry tributary of the Tshotshosi River in Zululand.

‘Miss O’Kane,’ Dartnell continued, ‘Lady Beecham, seems to have it in mind that she will be reunited with the empress and attend the memorial service. We have yet to ascertain the validity of her claims – enquiries are ongoing – but the lady will require an escort as she seems intent on visiting the key battlefields of the late campaign, as well.’

‘Sir . . .’

Dartnell held up a hand. ‘Still your inevitable protest, Gregory. Yes, I need to assign some poor fellow to chaperone the good lady, but there’s another reason why I’d like it to be you who retraces the steps of Lord Chelmsford’s campaign.’

Gregory pinched the bridge of his nose with thumb and forefinger. He felt dizzy and silver spots began appearing at the extremities of his vision, even as he closed his eyes.

‘Gregory!’

He opened his eyes. ‘Sir.’

‘Pay attention.’

‘Yes, sir.’

Dartnell exhaled, and his shoulders sagged a little. ‘You are one of my best officers, Peter, and undoubtedly the cleverest, if not when it comes to affairs of the heart.’

Gregory drew a breath and was ready to reply, but Dartnell shut him down with a raised hand.

‘Enough. What goes on between you and your Indian housekeeper is none of my business. No, Gregory, there is something else I need you to do for me.’

Gregory held his tongue. Dartnell sifted through more papers, until once again he found the one he was looking for. ‘I have here a missive from Lord Chelmsford. What I am about to tell you, Gregory, is in the strictest confidence. No one else must know of the contents of this correspondence. Do you understand?’

Gregory nodded. ‘Yes, sir.’ Chelmsford had been the overall commander of the invasion of Zululand at the start of the war, in January, 1879. It was he who had made the terrible error of splitting his forces and leaving his supply wagons exposed and under-defended at Isandlwana. They had been massacred, almost to a man. The heroic defence and British victory at Rorke’s Drift, which followed the disaster at Isandlwana, had not been enough to save Chelmsford’s job, but even though he was relieved of his command he led a final incursion back into Zululand. Chelmsford defeated the Zulu king, Cetshwayo kaMpande, at his imperial capital, Ulundi, before Chelmsford’s successor, Garnet Wolseley, could arrive to take the glory.

Dartnell’s eyes scanned the page, then he looked up. ‘When Lord Chelmsford returned to England after Ulundi, he sought and was granted an audience with the Empress Eugénie. His purpose, as well as conveying his condolences over the death of the Prince Imperial, was to return the young prince’s sword to his mother.’

Gregory pulled his head back a little in surprise. ‘They found Napoleon’s sword, sir?’ The way he’d heard it, the Zulus who had ambushed the small scouting patrol that the prince had been on had killed the heir to the Bonaparte dynasty, as well as two British soldiers and a Zulu scout working for the British. They then stripped the bodies, mutilated them, and took their weapons and uniforms.

Dartnell arched his eyebrows. ‘You say, “Napoleon’s sword”, Gregory. What do you mean by that? The prince’s weapon, or that of a more famous forebear?’

Gregory shrugged. ‘The latter. I remember some stories, sir. A friend of mine in the Royal Artillery, whose younger brother had trained with the prince in England, said that Prince Louis carried the sword of his great-uncle, Napoleon Bonaparte. He said the blade was that carried by the French Emperor at the Battle of Austerlitz.’

‘Indeed.’ Dartnell consulted the letter again. ‘But Chelmsford wrote the following to me: “On presenting the sword to Her Majesty she affected a look of surprise, followed by profound dismay, whereupon she told me that this was not her son’s sword, nor that of her husband’s uncle, Napoleon Bonaparte”. It seems Chelmsford had the wrong sword.’

‘How did Lord Chelmsford come across the sword?’ Gregory asked. He found himself leaning forward, elbows on his knees. There was something about a puzzle, a mystery, an odd question that excited him. It also had the welcome effect of pushing any other problems or maladies in his life into the background.

‘You remember the situation between the Zulus and our forces in the lead-up to Ulundi?’ Dartnell said, answering with a question.

‘Sir.’ Gregory nodded. ‘We wanted revenge after Isandlwana, but even when the second invasion happened, the Zulus did not rush to the fight again.’

‘Yes,’ Dartnell said. ‘King Cetshwayo may have basked briefly in his early victories, but he knew what the reaction would be. Accordingly, he sent out several envoys to try and negotiate with Chelmsford. However, His Lordship was intent on crushing the Zulus. One party of Zulus, under a senior officer named Mfunzi, approached a British patrol below the Mthonjaneni Heights, en route to the White Umfolozi River, under a white flag, and handed over the Prince Imperial’s sword. They claimed it was the weapon taken during the encounter and that they had since learned that their men had killed a great warrior, a nobleman from Europe. They offered the sword as a sign of good faith. Chelmsford took the sword, but refused to negotiate, and the rest is history. Except . . .’

‘Except it wasn’t the prince’s sword?’ Gregory asked.

Dartnell shook his head. ‘Oh, it was a French sword all right, but a common cavalry officer’s weapon. According to the empress it was certainly not the rather ornate blade carried by Bonaparte at Austerlitz – that one was apparently covered in rather ornate engravings.’

Gregory thought a moment. ‘How the hell would a French cavalry sword end up in Zululand?’

Dartnell leaned back in his chair, which creaked with the movement. Outside, cicadas screeched in the sun now that the rain was gone. He folded his hands over his stomach, fingers interlaced. ‘Exactly. And where is Napoleon Bonaparte’s famous sword now?’

Gregory looked his commander in the eye. ‘Sir?’

Dartnell leaned forward again on his elbows, closing the distance between him and Gregory. ‘I want you to make some enquiries, Gregory, discreetly, but posthaste. With the empress here now it is Lord Chelmsford’s wish that we do our utmost to find the real Napoleon’s sword and present it to her.’

‘But surely the army, sir –’

Dartnell held up a hand. ‘As you very well know, Lord Chelmsford was officially relieved of his post just before the Battle of Ulundi and was supposed to hand over command to General Wolseley. As it happened, Chelmsford snatched victory from the jaws of his own reputational defeat and Wolseley arrived too late for the last big battle of the war. There is bad blood between the men, and if Wolseley found out that Chelmsford had embarrassed himself by handing over the wrong sword then Wolseley would sully Chelmsford’s reputation further. It is a matter of honour for Lord Chelmsford.’

Gregory took in the information. In his experience, the foolish pride and honour of generals more often than not ended with the death of soldiers.

‘The empress is known in London as a woman of great generosity, who rewards the favour of those who serve her well,’ Dartnell added.

Sweetening the pot? The good Lord – and his newly minted servant Grace – knew that Gregory was proving to be a failure at farming. Perhaps Dartnell had also learned of Gregory’s parlous financial state. The funds from England had dried up with the death of his mother, and though nothing had yet been communicated formally, Gregory couldn’t help but wonder if word of his shame had reached the rest of his estranged family.

‘What is occupying your thoughts, Captain?’

Gregory realised he’d been lost in his own troubles. ‘Er, nothing, sir. Do you have any avenues of approach in mind as to where I can start looking for this missing sword?’

Dartnell ignored the question. ‘I know what troubles you, Gregory. I’ve read the full report of what happened at Isandlwana, and the accounts of the very few survivors of the battle.’

Rout, more like it. ‘Sir.’

Dartnell stroked his neat beard. ‘I wish that more people in the colony could have read that document – it would still some of the . . . innuendo. You and I know what happened.’

‘With respect, sir, I was unconscious for much of it.’

He nodded. ‘Yes, yes, yes, I know that. But we both know that those with idle hands and simple minds will gossip, and I am not unaware of how that has affected your social standing in the colony, Gregory. This mission, quest, whatever you will name it, to assist the empress, will be an opportunity to demonstrate the thoroughness and sense of duty and honour that I know you possess.’