5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

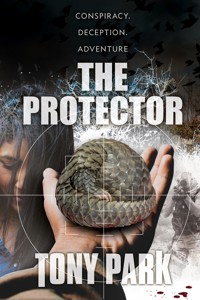

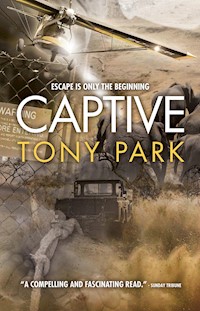

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A woman's quest to save Africa's wildlife turns lethal.

A very eager - and rather naive - Australian lawyer, Kerry Maxwell, flies into South Africa to volunteer at a wildlife orphanage run by notorious vet, Graham Baird.

Graham is as jaded and reckless as Kerry is law-abiding and optimistic. When Kerry arrives at the animal sanctuary it's to the news that Graham is imprisoned in Mozambique following a shootout with elephant poachers. In the gunfight he killed the brother of corrupt politician and poaching kingpin Fidel Costa.

Kerry's earnest sense of justice takes her to Massingir to help Graham with his case, and into a world of danger. Kidnapped, chased, attacked and betrayed, Kerry learns the bitter truth about the complexities and deadly nature of the war on poaching.

Even the motivations of well-meaning charities, wealthy donors and private zoos are not all they appear.

Kerry's perilous entanglement may be what Graham needs to shake off his drunken cynicism and rejoin the fight for Africa's animals, but is it enough, and in time, to stop Costa's quest for revenge...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

About Captive

A woman’s quest to save Africa’s wildlife turns lethal.

A very eager - and rather naive - Australian lawyer, Kerry Maxwell, flies into South Africa to volunteer at a wildlife orphanage run by notorious vet, Graham Baird.

Graham is as jaded and reckless as Kerry is law-abiding and optimistic. When Kerry arrives at the animal sanctuary it’s to the news that Graham is imprisoned in Mozambique following a shootout with elephant poachers. In the gunfight he killed the brother of corrupt politician and poaching kingpin Fidel Costa.

Kerry’s earnest sense of justice takes her to Massingir to help Graham with his case, and into a world of danger. Kidnapped, chased, attacked and betrayed, Kerry learns the bitter truth about the complexities and deadly nature of the war on poaching.Even the motivations of well-meaning charities, wealthy donors and private zoos are not all they appear.

Kerry’s perilous entanglement may be what Graham needs to shake off his drunken cynicism and rejoin the fight for Africa’s animals, but is it enough, and in time, to stop Costa's quest for revenge…

For Nicola

Contents

Author’s note

The problems facing Africa’s wildlife seem almost as numerous as the number of non-governmental organisations trying to protect and conserve it.

I am a supporter of several charities taking very different approaches to these issues, including anti-poaching, relocation of wildlife, conservation and demand reduction. There is no single solution to the problems of poaching and the illegal trade in wildlife products.

The organisations and people depicted in this novel may bear similarity to real-life bodies and individuals, but I assure you they are not based on any person or group.

Prologue

South Africa, 1998

Nsele was scared of nothing, nobody. Not lions, not leopards, not hyenas nor even the wild dogs, who were professional killers. What he lacked in height he made up for in attitude and ferocity.

He was a killer, and no one messed with him.

But he knew when it was time to run. Nsele leapt over a fallen log and scrambled under a thornbush. He felt no pain from the barbs that tried to hook him. He was invincible, he was young.

But he was scared.

Behind him his pursuers had taken to a vehicle. The Land Rover bounced over the open vleiof dry golden grass, flattening stems and lurching in and out of a landscape cratered by the sinking feet of elephants passing through here during the last rainy season. The black soil had hardened now into a hundred thousand potholes.

It didn’t slow him. Nothing could stop him.

If they cornered him, somehow, somewhere, he would kill them and their deaths would be vile and bloody.

If they wanted to kill him they would have done so by now. They had guns, and they’d had a clear shot at him, but they were still in pursuit. They wanted him alive.

Nsele had evaded traps in the past, amateurish affairs that were easy to circumvent and easier still to escape from. He would not be taken easily.

He ran and he ran, but the men were faster. Nsele scurried up and over a termite mound, but when he started sliding down the far side he saw he had run into a trap.

There, in front of him, was another open-topped Land Rover, parked and waiting. A man stood in the open rear with a dart gun.

‘Honey badger!’ The driver of the vehicle pointed at Nsele.

Nsele turned and tried to get over the mound again, but the dart left the weapon with a pffft, and Nsele felt a pain in his arse.

Chapter 1

South Africa, the present

Kerry Maxwell looked out of the window of the Embraer jet and gasped. She turned to the man in the khaki uniform of the South African National Parks across the narrow aisle. ‘It’s a giraffe!’

He smiled. ‘Ja, a big bull.’

‘Sorry,’ she said, feeling a little self-conscious. ‘You must see giraffe every day.’

He laughed, his big beer belly shaking. ‘I wish. I work in Pretoria in an office mostly; I’m almost as excited as you to be back in the Kruger Park. This your first visit?’

She nodded. ‘I’m so excited.’

‘Do you mind if I ask, where are you from?’ His accent was Afrikaans. ‘China?’

It was her turn to laugh. ‘No, Australia. I’m part Vietnamese.’ He looked over the top of his reading glasses. ‘You know, sadly, much of the rhino horn taken from animals that are illegally killed here in the Kruger Park ends up in Vietnam.’

‘I know.’ She didn’t think the man meant offence. ‘Actually, I’m involved with a charity dedicated to saving the rhinos. That’s why I’m here. I’ve come to learn more about the problem. The charity is all about reducing demand in Vietnam, and I’ve travelled there to work as a translator with our people who are placing anti-poaching advertisements in the news media.’

He smiled. ‘Good for you. We can’t win this fight with guns and bullets on the ground. My name is Danie.’

She shook his hand. ‘I’m Kerry-Anh, though people just call me Kerry. Anh was my mother’s name, she was half-French, half-Vietnamese.’

‘Was?’

‘She died, of cancer, two years ago.’

‘So sorry for your loss. That is a beautiful name, Kerry-Anh. Do you work for this charity fulltime?’

‘No, I’m a lawyer. I work for a firm in Sydney, but I’m taking two months’ long service leave. I try to help out in my spare time.’

‘Then welcome to South Africa. Where will you be staying?’

‘I’m first going to volunteer for a month at a wildlife rehabilitation centre at Hoedspruit.’

‘Ukuphila Wildlife Orphanage?’

‘Yes, that’s the place. I read on their website that the name means “life” in Zulu. I’m going to be working with a veterinarian. Dr Baird.’

Danie shook his head. ‘Eish, that Graham Baird.’

‘What does that mean?’

He smiled. ‘You’ll find out. Try and catch him before midday, though.’ The man pantomimed taking a sip of a drink from a bottle.

Kerry sat back in her chair, a little disconcerted. WhathaveI got myself into? she wondered.

*

‘That’s the Lebombo Hills over there in the distance, Doc. The Kruger Park’s on the other side, across the border,’ the helicopter pilot said into the intercom.

Graham Baird felt queasy. It wasn’t the flying – he’d been in and out of choppers for twenty-five years, since his time as a conscript in the South African Army and had a fixed-wing pilot’s licence. It was the beers last night. And the red wine. And the Scotch. And the brandy. He hadn’t expected to be flying today.

Graham burped. ‘I was working as a vet in that area before you were born.’

‘Whatever, Doc,’ said the pilot, Retief, who Graham thought looked about sixteen.

On the rear seat of the helicopter, next to Graham, was his plastic fishing tackle box full of drugs and darts, and some traces and lures in case he ever got the chance to hunt for some tigerfish in Mozambique’s rivers.

He was very familiar with the Kruger National Park, having worked there for the national parks board in his youth, but nowadays nearly all his work was done in and around the Timbavati Game Reserve and other neighbouring privately owned safari land on the western border of Kruger. Today, however, he was far to the east, on the Mozambican side of Kruger.

The Kruger Park, as big as the state of Israel, had been expanded even further in recent years across the border into Mozambique. The whole conglomeration was known as the GLTP, the Greater Limpopo Transfrontier Park.

All that meant to Graham Baird these days, however, was more space for poachers to hide in, and more dead and injured animals. He loaded a dart with M99, the potentially lethal opium derivative he’d need to sedate the elephant if they found it.

‘Last report had the baby elephant somewhere around here, running up and down the old fence line,’ Retief said.

Graham looked out the open side door, scanning the ground. It was a forlorn hope trying to find a lost baby elephant in all this bush, but his friend Juan Pereira, the owner of the newly developed lodge on the Mozambican side of the park, had been alerted to the calf’s plight by one of his guides, who had encountered it while taking some well-heeled American visitors on a game drive that morning. The visitors were investors in the lodge and had, by good fortune, arrived in a helicopter – the one Graham was in now.

As luck would have it – although his flip-flopping belly protested he was anything but fortunate – Dr Graham Baird had been visiting the lodge at Juan’s invitation to perform surgery on his dog, which had been seriously mauled by a leopard.

Graham looked up and scanned the horizon. He saw a swirl of black dots against the clear blue dry-season sky. They looked almost like a disjointed tornado. ‘Vultures, to the north.’

‘OK, Doc. I see them. You think that’s the baby’s mom?’

‘Could be.’

‘Bastards,’ Retief said.

Graham felt the same. It was bad enough having to deal with the scourge of rhino poaching on an almost daily basis, but in recent times there had been an upsurge in elephant poaching. It was hopeless; the killing never ended.

Retief headed in the direction of the vultures and the elephant carcass came into view. Retief settled into a hover nearby and they both searched the surrounding landscape. ‘Hey, there’s the baby! To the west.’

Graham shifted his binoculars. The distraught calf ran in circles.

‘Call the ground team,’ Graham said. ‘Give them the coordinates. We’re not far from the lodge and there’s a game-viewing road nearby. Shouldn’t take them long to get here.’ As soon as the two vehicles arrived, Graham would dart the elephant and then Juan could take it to wherever and whatever he had planned for it.

‘Roger, Doc. How about we take a bit of a joy flight while we wait for them?’

Graham rolled his eyes. ‘I’d rather die. Keep it straight and level.’

Far to the north the sun glinted on water Graham realised was Massingir Dam, on the Olifants River. He closed his eyes and laid his head against the padded insulation on the rear bulkhead of the chopper.

‘Doc!’

Retief’s voice roused him from the microsleep he’d fallen into. ‘What now?’

‘I’ve got people ahead, crossing a vlei, running.’

Graham lifted his binoculars and followed the pilot’s directions. He picked up the men, half-a-dozen of them, running through the waist-high golden grass of the floodplain. Two of them were burdened with long, curved ivory tusks.

‘Put me through to the ground team,’ Graham said. Retief patched him through. ‘Juan, it’s Graham. We’ve got six poachers in the open, about a kilometre southwest of the coordinates we gave you for the elephant, over.’

‘Copy, Graham,’ Juan said above the noise of his Land Rover’s engine. ‘What are they carrying?’

Retief keyed his microphone. ‘Looks like three with AK-47s, two carrying the tusks and the remaining guy with the tools.’

There was a pause on the other end. ‘Graham, I’ve got one rifle, my .375.’

‘Where’s your nearest anti-poaching patrol?’ Graham asked.

‘Eli Johnston’s working fifty kilometres south of us today. With the state of the roads here it will take him nearly two hours to reach you.’

Graham had met Johnston, a former US Navy SEAL who had left the military to devote his life to hunting poachers.

‘I’ll be out of fuel by then,’ Retief said. ‘I’ve got maybe thirty minutes remaining.’

‘Best we can do is keep them in sight for as long as we can,’ Graham said. ‘Juan, see if you can raise Eli or the police in any case.’

‘Roger.’

Retief cut in again, using their private intercom. ‘I’m going to buzz these guys, scare them.’

Graham shared the pilot’s frustration, but not his impetuous youth. ‘All I’ve got is my nine-mil pistol. I smuggled it into Mozambique.’

Retief reached under his seat. ‘Take mine as well.’ He passed a Glock 17 back to Graham.

Graham held a pistol in each hand. ‘What am I, Wyatt Earp?’

The pilot threw the helicopter into a steep banking dive. ‘You are now, partner.’

Graham tensed his whole body as the ground raced up towards them. Retief levelled out and the long grass on the floodplain flattened under the downwash. Graham saw the poachers dive in fear.

Retief was foolhardy, but Graham couldn’t fault his courage.

‘They’re not going to fire on us,’ the pilot said. ‘They don’t want to risk getting in that much shit.’

‘I’m not so sure about that,’ Graham said. ‘How about you back off, China.’

‘Negative, Doc.’

Retief turned tightly one hundred and eighty degrees, and came back for another low-level buzz. Graham saw two of the poachers pop up, their AK-47s pointed at the helicopter. ‘They’re firing.’

Graham heard the ping and thud of bullets penetrating the skin of the helicopter. He put both hands out in the slipstream and started firing back, the two pistols blazing as they passed over the men below. A bullet whizzed between Graham’s legs and he yelled with fright.

‘Sheesh, that was too close,’ Graham said. It was terrifying, yet at the same time exciting. Graham was momentarily taken back to his time in the army.

He looked back, the wind catching his hair. The poachers were running. The helicopter lurched sickeningly to the right. Graham stuck one pistol inside his open shirtfront and grabbed onto the seat. ‘Retief, what’s going on?’

‘Doc …’

‘What is it?’ Graham leaned forward and saw the blood.

‘I’m hit.’

Graham looked around him in the back of the helicopter. He saw a first aid kit clipped to a bulkhead and wrenched it free. ‘Hold on.’ He climbed awkwardly between the pilot and co-pilot’s seat.

‘Got to find somewhere to put her down.’

The helicopter slewed from side to side. Blood was spurting from the top of Retief’s thigh and his face was getting paler by the second. Graham fell into the co-pilot’s seat. He reached over and put his hand on Retief’s leg. ‘It’s your femoral artery. Shit.’

Retief tried to smile. ‘What happened to “reassure the patient”, Doc?’

Graham unzipped the first aid kit and the contents tumbled out into his lap and onto the floor. He found a wound dressing and ripped it open. When he lifted his hand from Retief’s leg the blood kept welling. He placed the dressing over the bullet hole. ‘Can you lift your leg?’

‘Not unless you want us to crash. I can see a clearing … up ahead.’

Graham kept pressure on the wound. ‘Hang on, you’ll be OK.’

Retief coughed and blood ran out of his mouth.

Graham used his free hand to feel behind the pilot. When he pulled away from Retief’s shirt he saw fresh blood on his hand. The bullet that hit him must have passed through his leg, nicking the artery, and carried on up into his body.

‘Can’t … can’t keep my leg steady. Brace … brace, Doc.’

Graham looked up and saw that the helicopter had tilted almost onto its right side. The ground rushed up at him. There was the sound of screeching metal as pieces of the rotor blades sheared off and flew at crazy angles as the helicopter smashed into the ground.

Chapter 2

‘I can take the meat off for you,’ said Lawrence, the Shangaan safari guide who had picked Kerry up from Skukuza Airport.

‘Thank you,’ Kerry said.

They had stopped at a picnic spot, a place called Nhlanguleni, which Lawrence explained was near the western border of the Kruger Park, and he had produced ham and cheese rolls from a cooler box for lunch. Kerry had politely explained that she was a vegetarian. She took a travel-sized bottle of hand sanitiser out of her daypack and thoroughly disinfected herself before eating.

The light seemed brighter and the sun even hotter than either Australia or Vietnam, the two countries she was most familiar with. The sky was a perfect endless blue. The picnic site was a clear patch of raked dirt with a few big trees for shade. There was no animal-proof fence, just a log and pole affair that Kerry suspected was more to stop people wandering. A few sets of green tables and chairs were occupied by families laying out food for lunch.

Lawrence pointed. ‘Look.’

‘Oh my God, it’s an elephant!’ She had seen zebra, wildebeest, and more beautiful giraffe already that morning, along with what seemed like thousands of impala, but this was another first.

‘Yes, we have many elephants in the Kruger Park,’ Lawrence said. ‘Some people say we have too many.’

Kerry raised her camera and fired away as the big lone elephant sucked up a trunkful of water from a man-made cement waterhole, set in an open plain about a hundred metres from the picnic site.

‘How can you have too many elephants? They’re a threatened species.’ Kerry realised she hadn’t put sunscreen on so she found her bottle and applied a liberal smearing of SPF 50 to her face and hands.

Lawrence stood beside her. ‘That is true. Elephants have disappeared from much of Africa, but in places where they are protected, like the Kruger Park, their numbers grow and grow each year. Parts of Kruger are suffering from elephants eating too much.’

A herd of zebra trotted across the plain and closed, nervously, on the waterhole. The elephant turned and took a few steps towards them, sending the skittish animals galloping with a spray of water from his trunk. They returned, though, once the elephant had drunk his fill and ambled away.

‘It’s breathtaking,’ Kerry said. She swallowed hard, experiencing a sudden foolish thought that she might cry.

Lawrence looked at her. ‘Don’t worry, I have seen people shed tears at the sight of their first wild elephant.’

They packed up and drove on. This, to her mind, was Africa as she had pictured it, with the harsh thorny trees giving way to open plains of golden grass.

‘Keep your eyes open,’ Lawrence said. ‘This area west of Satara Camp is very good for cheetah. They favour these savannahs.’

Kerry stared into the heat haze, willing a big cat to appear, but they reached the Orpen Gate without a sign of the predator. She told herself she had plenty of time to see all Africa had to offer.

*

Graham came to and smelled smoke. He lifted his head and his vision swam as he felt the pain, worse than any hangover he had ever experienced.

Something electrical was shorting. He caught the odour of burning plastic. ‘Retief,’ he croaked.

There was no answer from the pilot next to him.

‘Retief!’ He shook the pilot, then placed two fingers on his neck. No pulse. ‘Shit.’

He fumbled with the buckle for the pilot’s harness and dragged him free of the wreckage. He rolled the younger man onto his back and started CPR.

‘Come on.’ Graham moved from breaths to compressions, but got no response. Retief was dead. He heard voices. They were men, speaking Portuguese, calling to each other.

Graham shivered. It was the poachers. The ground crew from the lodge would be coming by vehicle. The men who had downed the helicopter would not want to leave any witnesses. He reached into his shirt for the pistol, pulled it out, and ejected the magazine. His wild gunfire had left just three rounds.

He went back to the wreckage of the helicopter and hurriedly searched the rear compartment, snatching up the only other weapon he could find: his dart gun. The other pistol must have fallen out of the helicopter during the crash.

Graham did a quick check of Retief’s shirt and shorts, but the pilot had no more ammunition. Graham looked down at Retief and crossed himself, then limped away from the helicopter.

When he reached a clump of thorn trees he dropped to his knees and wriggled into the dry undergrowth.

Three men armed with AK-47s came into view, moving with the professionalism of soldiers on patrol. Graham guessed that the other men, those carrying the tusks and the tools they had used to remove them, must have carried on towards their base or destination, leaving the armed men to investigate the crash.

The first gunman searched the helicopter, including Retief’s body, and after helping himself to the pilot’s wallet, called his comrades forward. They talked to each other in Portuguese as they ferreted around the crash site.

One poacher, an older man with tight curls of grey hair, circled the wreckage, his eyes on the ground searching for spoor. He called to the others. The youngest-looking man in the group, perhaps still a teenager, joined him, while the third stayed by the helicopter.

The youth looked at the tracks the older man was pointing out and then both looked up, following the trail towards where Graham lay. The old man put his hand on the younger one’s arm to caution him, but the youth shook off the touch and started heading Graham’s way.

Graham was a hundred metres or more from the wreckage, too far for an accurate pistol shot. He picked up the Dan-Inject dart gun he had been about to use on the baby elephant, took aim through the telescopic sight and centred the crosshairs on the young man heading his way.

The youth paused, then pointed directly at Graham and yelled something over his shoulder, in Portuguese, to the older man. The boy raised his rifle and started to take aim.

Graham pulled the trigger. The dart flew true, and the young man fell. Graham changed weapons as the other two men, calling to each other, raised their assault rifles and opened fire.

The elder of the group hung back, but the man who had been checking out the downed helicopter ran forward. Graham stood, wrapped his left hand around his right and fired a shot at the man coming towards him, aiming for the centre mass of his body. The man fell backwards and lay unmoving. Graham dived for the ground and rolled, then crawled for the cover of a fallen tree.

The old poacher fired a wild burst of three rounds from his AK-47 then turned and ran.

Graham fired his last two bullets at the fleeing man, but neither shot found its mark. He stayed in cover until the man was out of sight.

He stood, dusted himself off and walked to the young man he had darted. The boy was immobilised, but still conscious. He blinked twice.

Graham knew he should draw up a syringe of naltrexone, the same drug that paramedics administered to heroin addicts who had overdosed, to reverse the effects of the dart. His tackle box was somewhere in the wreckage.

He jogged to the helicopter and paused, briefly, to look at Retief’s body. In the back of the helicopter he found his tackle box full of drugs, but it had come open on impact and phials, syringes and ampoules were scattered everywhere. By the time he had found and drawn up a syringe of naltrexone, and made it back to the poacher, the young man was dead.

*

Kerry and Lawrence pulled up at the reception office of Ukuphila Wildlife Orphanage, near Hoedspruit.

Kerry walked into the thatch-roofed building which was painted a similar khaki hue to the bush she’d been passing through all day. She was tired, but pleased to be at her destination. Except there was no one at the reception desk. She rang a bell on the counter. As well as housing a variety of birds, animals and reptiles, Ukuphila’s grounds also included a dozen two-person accommodation units. Kerry saw a whiteboard behind the counters that bore the heading Chalets.

Next to the numbers one to twelve were various surnames. Oddly, hers wasn’t there; perhaps, she mused, the board had yet to be updated.

Lawrence came in behind her, pulling her wheelie bag.

A portly lady walked slowly through a doorway from a back office. ‘Hello, how are you?’

‘I’m Kerry Maxwell. I’m here for the month-long volunteer program with Dr Baird.’

The woman seemed miffed at something. ‘Ah, but Dr Baird, he is not here today.’

Lawrence and the woman exchanged what seemed like extended words of greeting in their language and Kerry wondered if she should have been more polite, instead of coming straight to the point.

‘Can you tell me when he’ll be arriving?’ Kerry asked.

The woman shrugged.

Kerry looked back at Lawrence, but he just smiled. Kerry took a deep breath to still her growing impatience. ‘OK. Perhaps I can check in to my room and you could let me know when Dr Baird arrives.’

‘Your name?’

Kerry took a deep breath. ‘Maxwell.’

The woman clicked a computer mouse and looked at the monitor.

‘There is no one by that name booked with us.’

Kerry leaned over the reception counter. ‘Let me see.’

The woman frowned at her, but turned the monitor slowly her way.

Kerry scanned the names. ‘I’m not here. You look busy.’

‘We are fully booked. There is a wedding happening tomorrow.’ ‘You mean you don’t have any accommodation for me?’ She felt her heart rate start to rise. ‘I sent my money to Dr Baird and he confirmed my booking.’

‘Dr Baird, he is not here.’

Kerry felt a panic attack coming on.

*

Graham Baird drank slowly but steadily all the way to the town of Massingir.

Juan had picked him up and taken the bodies of Retief Potgeiter and the two poachers Graham had killed back to his lodge, where they had collected Graham’s Land Rover. Graham followed the lodge owner on the drive to town where they would have to report to the Mozambican police. Graham wasn’t looking forward to the inevitable bureaucratic marathon that would ensue, so he worked his way steadily through a sixpack of warm Dois M beers as he drove in order to prepare himself and to steady his nerves.

Massingir was dominated by the dam of the same name, a low but five-kilometre-long wall that held the Olifants River in check for a while on its journey from South Africa into Mozambique.

The town had sprung up around the dam and was, year by year, eating up more of the surrounding bushland. There were high hopes that one day tourists would flock to the lake created by the dam to fish and view game, but for now a good deal of the money that paid for the newer houses and the four-by-fours that honked and bumped their way around Massingir came from poaching.

A Mozambican poacher could make well in excess of the country’s average annual income from the proceeds of shooting one rhino across the border in the Kruger Park, while the kingpins who supplied the animals’ horns to the Vietnamese middlemen were akin to local royalty.

Graham crumpled an empty beer can and tossed it on the floor of the passenger side of his Land Rover, where it clanged against the first three. He had a nice buzz on, though it wouldn’t be enough to see him through the day.

Juan led the way past market stalls that were selling tomatoes and second-hand clothes donated by well-meaning do-gooders overseas, and pulled up outside the town’s police station.

Graham parked behind him and got out.

‘Stay here, for now, my friend,’ Juan said, then went inside.

Three police officers filtered out of their bunker with Juan. They clustered around the bakkieloaded with the bodies of the dead poachers. Retief was wrapped in a green waterproof poncho in the rear of Graham’s Land Rover.

The policemen chatted among themselves, one took notes, and a couple took pictures with cheap Nokia phones. They came to Graham and the one who seemed to be in charge started berating him.

‘He says you are to be charged,’ Juan said.

‘Then tell him I am very sorry for any offence I have caused to the peace-loving people of Mozambique, but now is the time for me to go back across the border to South Africa.’

Juan did some translating. ‘The officer says this is not possible, for now.’

It was hot. Sweat streamed down Graham’s face and he thought it could be the beers evaporating from him. He felt light-headed.

The senior policeman was taking notes now, still speaking only in Portuguese.

Juan looked Graham in the eyes. ‘He says one of the men you killed was the little brother of a local politician, Fidel Costa.’

‘Hah!’ Graham said. ‘You know as well as I do he’s the biggest criminal in town, and supposedly the local rhino poaching kingpin. What are they charging me with, manslaughter?’

Juan shook his head, his expression grim. ‘Murder.’

Chapter 3

Kerry was fuming. With no accommodation available at the Ukuphila Wildlife Orphanage, Lawrence had driven her to the only place in Hoedspruit he could think of that would have a room available.

She was in a place called Raptor’s Lodge, a collection of self-contained accommodation units on the edge of the Raptor’s View wildlife estate, a housing development set in the bush and populated with animals as well as people. It would have been very pleasant if she didn’t feel like a landlocked castaway.

Her Australian mobile phone was picking up a roaming signal. She tried the Ukuphila number for the third time that afternoon and Thandi – she was now on first-name terms with the receptionist – answered.

‘Is there any more news about where Dr Baird is, when he’ll be coming back?’

‘Ah, I have some bad news and some good news answers for you.’

Kerry sighed. ‘Good news first, please, Thandi. I need some.’ ‘The good news is that I have found your booking. The problem is that we were not expecting you until this time next month. I think this is Dr Baird’s mistake. He can be – how should I say – less than attentive to detail, particularly after lunch. I also now know where Dr Baird is. His friend, Juan, the lodge owner he was visiting in Mozambique, called just now.’

‘And?’

‘And that is the other news – the bad news. Dr Baird is in prison in Mozambique.’

Kerry plonked herself down in one of the cane chairs in the small lounge room of her unit. ‘Where? What’s he done?’

‘Ah, he is in Massingir, in Mozambique. He has been charged with murder.’

Kerry was speechless. How could this be happening to her? She took a deep breath and tried to think straight. Kerry realised she had so far only been thinking about herself.

‘What was Dr Baird doing in Mozambique?’ she asked Thandi. ‘He was trying to save a baby elephant whose mother had been killed by poachers. Dr Baird’s helicopter was shot down by poachers. The pilot died in the crash and Dr Baird was involved in a gun battle with the criminals.’ Thandi relayed the news in the same tone as she might have if Dr Baird was stuck in traffic. Kerry felt like she’d been physically floored for the second time in as many minutes. Here she was worried about her ruined holiday while a man who put his life on the line to save Africa’s wildlife was rotting in a third-world prison.

‘Do you have a number for this Juan guy?’

‘Of course.’

‘Good. Give it to me, please.’ Kerry scribbled down the number. ‘Thanks, Thandi.’

Kerry dialled the number and a man answered in what she assumed was Portuguese. She introduced herself and explained who she was.

‘Ah, I’m sorry to hear about your predicament,’ Juan said.

‘I wish I could tell you Graham will be out of prison soon, but the justice system in my country moves very slowly. I’m doing what I can behind the scenes.’

‘Does Dr Baird have a lawyer?’

‘Alas, no,’ Juan said. ‘I’m not sure I can find a good lawyer to represent him and, anyway, I know from my own dealings with my friend Graham that he is not a wealthy man. I usually end up covering his bar bill. However, I’m also having cash flow problems. I’m going to ask the police if Graham can perhaps pay a fine – what you might call a bribe – but even if they agree I’m not sure where we would raise the money if it is expensive. For a murder charge it is likely to be extortionate.’

‘I’m a lawyer,’ Kerry said.

‘You are?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then perhaps you could …’

The call ended. Kerry called Juan again but there was no answer, just a recorded message in Portuguese, repeated in English, telling her that the phone user was out of range or not in contact. She made five more attempts to call Juan, but could not get through.

‘Damn.’ Kerry felt helpless, but she was not only concerned for herself. A man was in trouble and needed legal help. She phoned Ukuphila again. ‘Hello, Thandi?’

‘Yes?’

‘Do you know where I can rent a car to drive to Mozambique?’

*

The rum was at room temperature, which was to say, close to boiling.

The cell smelled of old sweat and recent urine and the odours, like Graham himself, were ripening in the stifling October heat. Juan had smuggled in a bottle of Tipo Tinto, home-brewed rum sold in old plastic Coca-Cola bottles. The spirit was like sandpaper going down, but it was the only thing keeping him half-sane, as in half-drunk.

Graham willed himself to be patient. Juan would be pulling strings in the provincial government offices. It would just take time; Africa time.

A cockroach scuttled from out of the drain hole in the stained sink in the corner of the cell, looked around, twitched its antennae, then retreated.

‘Wise move, China.’ Graham raised his bottle to the departing bug. ‘The sewer’s cleaner. Probably smells better, as well.’

Graham heard voices speaking Portuguese. Keys rattled in the lock and a warder opened the door. ‘Come.’

He stood, his nose rankling at his own odour, and followed the policeman down a corridor with stained walls. They went into an office. A policeman sat at a battered wooden desk, his white shirt straining at the buttons over his corpulent belly. The man smoked while he perused a handwritten file. He looked up.

‘Doctor Baird,’ said the seated officer.

‘Sit,’ said the warder. ‘I will make the translation.’

The officer, older and clearly more senior, spoke in Portuguese, his words as sluggish as the blades on the ancient desk fan that squeaked as they failed to make headway against the humidity.

‘This is Capitão Alfredo. He says you are in big trouble.’ ‘Don’t worry. Tell him I’m innocent.’

The younger officer translated and Captain Alfredo regarded him through heavy, sleepy lids. ‘Guilty,’ the captain said in English.

‘I want a lawyer,’ Graham said.

The captain stubbed out his cigarette in an overflowing ashtray, listened to the translator, then shook his head. He spoke again.

‘The captain, he says there is no need for a lawyer, or a trial. He says he is able to deal with this matter with a fine.’

Graham nodded. He’d expected, hoped, this might be the case. His number one priority was to get out of this stinking place and back to South Africa, not clear his name in the eyes of the Mozambican justice system. ‘Ask him how much.’

There was a discussion between the two officers.

‘Five thousand,’ the warder said.

‘Meticais. Sure, no problem.’ Graham didn’t even bother bargaining. The price was too good to be true.

‘Unfortunately not.’

‘Rand?’

‘No, US dollars,’ said the warder.

‘What!’ Graham didn’t have anything like that much money. ‘That’s criminal. My life’s not worth that.’

‘The captain takes offence at your words.’

‘Well, tell him some more words from me. How about he …’

Captain Alfredo held up a hand and spoke low and slow to the translator.

‘The captain says you would be wise to consider paying this fine. He says there are other men in Massingir who might want to come and visit you.’ The warder moved behind Graham and grabbed his upper arm, motioning for him to stand. It was time for him to go back to his cell. ‘You would not like these visitors.’

Chapter 4

Kerry left Letaba Camp in the Kruger Park at dawn, just as the security gates opened. At the four-way stop she turned right, to the north.

She gripped the steering wheel of her rented Corolla hard and her eyes swept left and right, looking for elephant or other game that might suddenly jump out from the mopane trees into her path. Off to her right a herd of buffalo, perhaps two or three hundred of them, were plodding, single file, towards a concrete trough at a man-made waterhole fed by a windmill-driven pump. She slowed, but didn’t stop to take a picture. Yesterday she’d been in a kind of limbo, heading from the Kruger Park’s Orpen entrance gate north to Letaba Camp.

On her afternoon drive through the reserve, at a sedate pace dictated by the speed limit, she had almost convinced herself not to go to Mozambique, and rather just enjoy the spectacular wildlife and scenery around her. The countryside from Orpen to Satara, the first camp she’d stopped at, was sparse and open and she’d been treated to a sighting of a cheetah. She had watched, barely daring to breathe, as the cat had stalked an impala, then showed itself and gave chase. Puffs of red dust had erupted like mini explosions, signalling where the cheetah’s paws hit the ground. It had turned, dramatically, using its long tail as a rudder, and made a desperate lunge for the impala, but the lucky antelope had got away.

At Letaba Camp she had stayed in a rondavel, a round hut overlooking the wide sandy banks and glittering blue river of the same name. A dainty bushbuck, a milk chocolate brown antelope with white icing stripes, had walked up to her while she’d sat at a little table outside her chalet, beseeching her for a snack with its big glistening eyes. She’d seen signs warning tourists not to feed the animals, so she hadn’t.

Over dinner at the camp restaurant, while she’d watched a big bull elephant drink, Kerry’s doubts had surfaced. She’d spent a restless night and, thanks to a mix of jetlag and apprehension, had woken at five, before her alarm went off.

And now she was heading to her second African country in three days. Mozambique.

The road she followed climbed up into the Lebombo Hills, which marked the physical barrier between South Africa and Mozambique, and eventually led her to the Giriyondo border post. The formalities on the Kruger side were painless, though slower once she drove through the short no-man’s land into Mozambique. There were forms to fill in, for her and her rental car, an expensive visa to purchase, and she had to produce documents and a letter from the hire company to prove she had permission to take the car out of South Africa.

Kerry showed the customs officer on duty that she was bringing nothing into the country then set off through the Mozambican side of the reserve. Here there was less game but she drove through forests of towering mopane trees. She guessed that one side effect of the poaching that had plagued this part of Africa in decades past was a lack of megafauna, such as elephants, to thin out the vegetation. It seemed a sad irony that while the Kruger Park, according to Lawrence, had too many elephants, on this side of the border there seemed to be very few.

Kerry passed through a village and an exit gate from the park and finally drove onto the low, curving wall of Massingir Dam. She took it slowly, and forced herself to breathe deeply and calm herself for whatever she might encounter next.

Massingir itself burst her peace bubble. Children ran alongside her car, shouting and holding their hands to their mouths. The buildings looked ramshackle, either decaying old colonial edifices of brick and cement or shacks made of salvaged anything. Here and there were new structures with whitewashed walls and tin roofs, bureaucratic beneficiaries of foreign aid, but for the most part the residents and businesspeople of the town appeared to inhabit the south side of the poverty line.

Though not everyone.

A horn blared behind her and Kerry saw a black BMW X5 four-by-four in her mirror, flashing its lights at her and doing its best to mate with her rear bumper. She slowed and pulled over. The big car, with its dark tinted windows, roared past her.

A little further down the road she saw a new Range Rover and, somewhat incongruously, a low-slung Audi Q5 parked next to it. A few people in this dusty corner of Africa clearly had money to burn.

Kerry pulled over and checked her GPS, trying to find the police station. It was on Google Maps, but she couldn’t quite tell which street she was in. A banging on her window gave her a fright. It was a small boy. Kerry wound down the window.

‘Police. Er, Policia?’ she tried.

The boy nodded. ‘Sim.’ He pointed to a road ahead and crooked his hand to the right.

‘Thank you. Obrigado.’ She recalled the Portuguese word for thank you from a trip to Macau long ago with her parents. She missed her mother, still, terribly. What would her father think of her being here, on her mission? she wondered. It would be better to tell him when she got back to Australia.

The little boy was running after her as she drove off, doing his best to keep up with her, waving his hands. She wondered if she should have given him money.

Kerry slowed again and saw a large building on her right. It was surrounded by a wire fence, and a man in a white shirt with what looked like police insignia sat on a wooden stool by a gate. He had an assault rifle cradled on his lap. Kerry swallowed hard.

*

‘Visitor.’

‘What?’ Graham Baird blinked and coughed. The cheap rum had stripped his throat. He went to the steel door. When it opened he had to blink again. Standing in the gloomy, smelly corridor was a young woman in safari clothes. She had jet-black hair, almond-shaped eyes like a cat’s, and honey-coloured skin.

‘Dr Baird, I presume.’ She forced a smile at her own joke.

‘Howzit. Do I know you? I hope so.’

‘My name is Kerry-Anh Maxwell.’ The corners of her mouth turned down. ‘I was supposed to be staying with you right now at Ukuphila.’

‘You were?’ Graham scratched his head. Her accent sounded Australian, not quite what he’d expected. The penny dropped. ‘Oh. I thought you were due next month, or something like that. I’m supposed to be in Zimbabwe next week.’

‘Er, no, Dr Baird, I was supposed to be with you now, in South Africa. We can discuss all that later. I’m a lawyer, I’ve come to help you.’

Graham burped and was slightly ashamed of the invisible wave of stale booze that washed over Kerry. ‘Well, Miss …?’

‘Maxwell.’

‘Miss Maxwell, I’m afraid there’s not much you can do for me. I can’t afford the bribe the cops here want to let me go, so I definitely can’t afford a lawyer.’

She looked around the cell, and back at the warder, who was leaning on a wall in the corridor behind her. ‘I know you can’t afford legal representation; your friend Juan told me already. So what do you intend on doing?’

He shrugged. ‘Wait. This is Africa; sometimes that’s all you can do. If you spoke to Juan then you probably already know he’s trying to pull some strings for me.’

Kerry pursed her lips. ‘I don’t think you heard me. I’m here to represent you. I hear you killed a poacher.’

‘No, I killed two.’ Graham sighed. ‘Like most foreign volunteers you think you can change the world, but I don’t think you heard me, either. This is Africa.’

She put her hands on her hips. ‘What’s that supposed to mean – that justice doesn’t count and that you don’t deserve a fair trial with legal representation?’

‘Pretty much.’

She stomped a foot.

Graham laughed. ‘Did you just stomp your foot?’

‘Don’t mock me, Dr Baird.’

‘If I were you, Miss Maxwell –’

‘Kerry-Anh or Kerry for short.’

‘All right. If I were you, Kerry-Anne –’

‘It’s Anh, not Anne. It’s Vietnamese. Try Kerry if that’s too hard to pronounce.’

‘Well, Kerry, my advice to you is to go back across the border to South Africa and enjoy the rest of your holiday. Oh, and please don’t shoot any more of our rhinos on your way out of the country.’

She strode across the cell to where he was sitting and raised her hand. Graham recoiled, but was too late. She slapped him, hard, on the face. The guard in the corridor chuckled.

*

Kerry stepped back. She was shocked and surprised, and embarrassed. She had never hit anyone in her life. She was amazed that this dishevelled man, who smelled of alcohol and acrid sweat, had got under her skin so quickly.

But she was not sorry. ‘How dare you, you racist, arrogant, ungrateful criminal.’

‘Hey, I’m not a criminal.’ He rubbed his cheek. ‘Quite a right hook you’ve got there.’

‘You took my money. I was supposed to be spending a month with you, right now, helping you tend to injured wildlife.’

‘Sure. I’m the only injured wildlife here at the moment. I don’t think I would have survived a week with you, lady.’

She looked down at him. ‘Can’t you be serious about anything?’

‘You want to come to Africa and save the cute little animals?’

She bridled again. The man was impossible. ‘I want to do something. I want to help stop the slaughter.’

He ran a hand through his lank, greasy, greying hair. ‘Well, I was part of the slaughter yesterday. I saw a good man die and I killed a couple of others. That serious enough for you?’

Now she saw the pain in his eyes and wondered if the redness wasn’t just from the alcohol he’d been consuming.

‘Visiting is over,’ said the guard in the corridor. He walked into the cell and put his hand on Kerry’s elbow.

She shook him off. ‘Don’t touch me.’

‘I’d listen to her, comrade,’ Baird said to the guard. ‘She’s dangerous.’

Kerry started to leave, but turned back to the man on the concrete bed. ‘Dr Baird …’

‘Graham.’ His voice was softer now and his big frame sagged. ‘And I’m sorry, for what I said before.’

‘Thank you, for what you’re doing, trying to save wildlife.’

‘Don’t thank me. And do what I told you. Go back to South Africa. I’ll be all right. They’ll get sick of me here after a while, and if I’m not out of here by next week I’ll get your money back to you, somehow.’

‘I didn’t realise how traumatic all this must have been for you. I’ll get you released.’

‘Whatever.’ He lifted his hand in a half-wave and Kerry walked out of the cell.

He was infuriating, she thought, but he had just been through a trauma. Kerry had come too far to give up just yet.