Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Publicacions de la Universitat de València

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Biblioteca Javier Coy d'Estudis Nord-Americans

- Sprache: Englisch

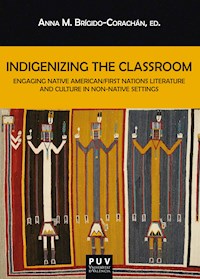

In the past four decades Native American/First Nations Literature has emerged as a literary and academic field and it is now read, taught, and theorized in many educational settings outside the United States and Canada. Native American and First Nations authors have also broadened their themes and readership by exploring transnational contexts and foreign realities, and through translation into major and minor languages, thus establishing creative networks with other literary communities around the world. However, when their texts are taught abroad, the perpetuation of Indian stereotypes, mystifications, and misconceptions is still a major issue that non-Native readers, students, and teachers continue to struggle with. To counter such distorted representations and neo/colonialist readings, this book presents a strategic selection of critical case studies that set specific texts within cross-cultural contexts wherein Native-based methodologies and key concepts are placed at the center of the reading practice. The challenging role of teachers and researchers as potential intermediaries and responsible disseminators of what Gayatri C. Spivak calls "transnational literacy" as well as the reception of Native North American works, contexts, and themes by international readers thus becomes a primary focus of attention. This volume provides a set of critical analyses and practical resources that may enable teachers outside the United States and Canada to incorporate Native American/First Nations literature and related cultural and historical texts into their teaching practices and current research interests in a creative, decolonizing, and responsible manner.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 356

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

INDIGENIZING THE CLASSROOM

ENGAGING NATIVE AMERICAN/FIRST NATIONS LITERATURE AND CULTURE

IN NON-NATIVE SETTINGS

BIBLIOTECA JAVIER COY D’ESTUDIS NORD-AMERICANS

https://puv.uv.es/biblioteca-javier-coy-destudis-nord-americans.htmlhttps://bibliotecajaviercoy.com

DIRECTORA

Carme Manuel(Universitat de València)

INDIGENIZING THE CLASSROOM

ENGAGING NATIVE AMERICAN/FIRST NATIONS LITERATURE AND CULTURE

IN NON-NATIVE SETTINGS

Anna M. Brígido-Corachán, ed.

Biblioteca Javier Coy d’estudis nord-americansUniversitat de València

Indigenizing the Classroom: Engaging Native American/First Nations

Literature and Culture in Non-Native Settings

© Anna M. Brígido-Corachán

1ª edición de 2021

Reservados todos los derechos

Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial

ISBN: 978-84-9134-748-4

Imagen de la cubierta: Navajo Ye'ii Tapestry Ca. 1920-30. Wool, 61 x 92.

Collection of the McNay Art Museum, Bequest of Marion Koogler McNay

Diseño de la cubierta: Celso Hernández de la Figuera

Publicacions de la Universitat de València

https://puv.uv.es

Edición digital

Contents

Reframing Our Pedagogical Practice.

Teaching Native American/First Nations Literature and Culture through Indigenous-centered Methodologies

ANNA MARIA BRÍGIDO-CORACHÁN

Pedagogies of Language Sovereignty

PHILLIP H. ROUND

Addressing Matters of Concern in Native American Literatures: Place Matters

CHRIS LALONDE

Buffalo Man: Human-Animal Transformations in American Indian Fiction and Its Reception by Polish University Students

GABRIELA JELEŃSKA

An Interdisciplinary Approach to Teaching Pocahontas

TERESA GIBERT

‘With them was my home’: The Politics of Native Space in A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison

ELENA ORTELLS

Teaching Native American Literature in Argentina

MÁRGARA AVERBACH

Native American Children’s Literature in the English Language Education Classroom

DOLORES MIRALLES-ALBEROLA

Indigenizing Afroperipheralism in Wayde Compton’s The Outer Harbour

VICENT CUCARELLA-RAMON

Identity (and Other) Lessons: Creative Writing in the Classroom as a Door into the Poetry of Ralph Salisbury

INGRID WENDT

Acknowledgments

This collective volume hopes to add to the growing discussion of Native American writing and critical pedagogies in the classroom. The idea to put this collection of pedagogical experiences, theories, and proposals together came after my participation in several international conferences (American Indian Workshop Resurgence and Resistance, London 2017, Small/Minor Literatures and Cultures: A Preliminary Debate, Santiago de Compostela 2017, and Teaching and Theorizing Native American Literature as World Literature, València 2018), and was inspired by the enlightening conversations held with many colleagues working in the field of Native American/First Nations and ethnic literary studies outside the United States and Canada. The challenges of teaching Indigenous American literatures in a foreign, non-Native setting are certainly greater for some of the reasons tackled in the chapters that follow. I would especially like to thank Ewelina Bańka, Silvia Martínez-Falquina, Gloria Chacón, Joanna Ziarkowska, Robert E. Lee, Gordon Henry Jr., David Moore, Kate Shanley, Sharon Holm, Rebecca Tillett, Aitor Ibarrola, César Domínguez, Susana Bautista, Sue P. Haglund, and Juan G. Sánchez for the inspirational exchange of ideas and classroom stories on Indigenous-centered theories and pedagogies and also thank Belén Vidal, María del Pilar Blanco, and Ana Fernández-Caparrós for their academic support and friendship. I am also most thankful, of course, to the amazing contributors to this volume for sharing their pedagogical experiences and wisdom with such commitment and passion.

An immense debt of gratitude and appreciation is also owed to my colleague, mentor, and friend, Carme Manuel—an extraordinary editor and a continuous source of inspiration in the classroom. This book would not have been possible without her insightful advice, generous assistance, and constant support, as well as that of the Conselleria d’Innovació, Universitats, Ciència i Societat Digital (Generalitat Valenciana), which provided funds for our research project “Las literaturas (trans)étnicas norteamericanas en un contexto global: representaciones, transformaciones y resistencias” (Ref. GV/2019/114).

Lastly, I would like to express my warmest gratitude to my students for their enthusiastic reception of Native American literary works throughout the years, in New York University and at the University of Valencia and, most dearly, thank my wonderful family—my parents, my partner Alex, and my precious children—for their unconditional love, patience, and emotional support.

Reframing Our Pedagogical Practice

Teaching Native American/First Nations Literature and Culture through Indigenous-centered Methodologies

Anna Maria Brígido-Corachán1

Universitat de València

There will be no balance

without all voices present in the power circle.

Joy Harjo, An American Sunrise

In the past four decades Native American/First Nations Literature has consolidated itself as a literary and academic field and it is now read, taught, and theorized in a variety of educational settings outside the United States and Canada. Native North American texts have also broadened their themes and readership by exploring transnational contexts and foreign realities, and also through translation into major and minor languages, thus establishing creative networks with other literary communities around the world. However, when Native texts are taught in foreign contexts, the reproduction of Indian stereotypes, mystifications, and misconceptions is still a major issue that non-Native readers, students, and teachers continue to struggle with. This is even more the case in non-US/Canadian settings, where direct contact with contemporary tribal cultures and practices is non-existent and where constant exposure to cliché representations of Indians in popular culture (through mainstream films, books, cartoons, advertisements, toys, sports mascots, etc.) may lead students to believe that Indigenous cultures in 21st century North America have either vanished or are circumscribed to dystopic, alcohol-ridden reservations.

When teaching Native American/First Nations literature, history, and culture in Spain, lecturers face an additional set of challenges that add to the potential misunderstanding, appropriation, mystification, and prejudice that commonly arises in non-Native classrooms in North America: students are no longer familiar with mainstream cultural references featuring Native communities and individuals in literature, films, or TV. They have never seen a western, an episode of The Lone Ranger and Tonto, or a Washington Redskins football game on TV. Their personal interests have shifted to other areas, channels, and formats such as social media or video games, while their cultural references have broadened and now include global cultural products such as K-Pop, reggaeton, or Turkish soap operas, with North American output quickly losing its dominant share of the cultural market.

When asked to imagine and describe an Indian, millenials and post-millenials in Spain have vague associations that reduce Native cultures to feathers and moccasins, teepees, buffaloes, and to (Disney’s) Pocahontas. A student or two in each classroom may be able to identify colonial realities and themes such as settler occupation, tragedy, and genocide or may mention Christopher Columbus’s historical error that led to the agglutination of extremely diverse Indigenous cultures under the false colonialist category Indian. But our students at the University of Valencia, for example, are rarely able to identify more modern stereotypes and areas of concern such as alcoholism and trauma, casinos, New Age shamans, social and environmental racism, political sovereignty, or cultural appropriation. In a way, it is perhaps best that their imaginaries are limited to romanticized lore (Disney’s Pocahontas is still a feminist model for many of our female students) because it reduces the number of clichés that must be interrogated. However, filling all of our students’ cultural and historical gaps in one semester (or a monthly unit!) while they read Native literary texts and Indigenous-centered scholarship is certainly a daunting task.

Compounding this difficulty, Native North American literature rarely stands as a module in and of itself in most universities around the world, even in North America. It shares classroom space and student attention with other US, Canadian, minority, postcolonial, or world literatures. Native American/First Nations literature is most often introduced within US or North American literature survey courses, Postcolonial literature courses, or cross-disciplinary modules that engage history, anthropology, trauma, memory, law, or space in the Americas, among other topics and fields. And given the geographical and cultural broadness of such topics and fields, delving into the specific tribal context of each of the texts that are engaged in the classroom is imperative. This context includes tribal histories, epistemologies, critical perspectives, literary styles, cultural practices, religious ceremonies, or political and legal frameworks, among others, and to provide some pedagogical strategies towards this ultimate goal has been the aim of all the essays included in this collection.

In her pioneering critical and pedagogical anthology Studies in Native American Literatures, Paula Gunn Allen argued that Indigenous works should be always approached from a holistic perspective that establishes “context and continuity” as the leading threads (xi). To that end, considering the complexities of a classic term such as cultural relativism and helping our students acknowledge the very notion of culture as a flexible concept in a continuous state of change is always our starting point, which is necessary to challenge the cliché of the pre-modern Indian right from the first class. Following Allen, some of the themes and strategies that emerge in recent scholarly works aiming to Indigenize the curriculum in the Americas or in Aboriginal Oceania also place a strong emphasis on keeping a local/tribal focus while exploring traditional and contemporary Native views on identity, nature, hi/story, or ceremony, among others.

Today, most scholars agree that Native American, First Nations, and Indigenous literatures must be engaged from Indigenous-centered methodologies, discourses, and frameworks (Armstrong and Blaeser 1993, Womack 1999, Reder and Morra 2016), that is, from an “Indigenous-centered,” “Native-based,” or “Indigenously-engaged epistemology and pedagogy” (La Rocque in Reder and Morra 58), rather than a Western, universal, or pan-Native perspective. Western thought and the pedagogical practices that set it at its center have traditionally excluded Indigenous epistemologies and methodologies from academia but these two sets of discourses and approaches to knowledge are not, by any means, mutually exclusive. In fact, room must be made for both in US/Canadian and also in non-US/Canadian classrooms. As Devon Mihesuah and Angela Cavender Wilson argue in their poignant volume Indigenizing the Academy, we need to “carve a space where Indigenous values and knowledge are respected” and also help to “create an environment that supports research and methodologies useful to Indigenous nation building” (2).

In my 14-year experience within the Spanish academy, incorporating Indigenous perspectives and pedagogical strategies has certainly enriched our students’ understanding of the world, enhancing their awareness of other cultures and realities, making them more empathetic, mature, respectful, and globally-minded citizens. In many cases, such awareness of contemporary Native American realities, historical struggles, and worldviews has been transformational and led to a sustained commitment to cultural, epistemological, and linguistic diversity and, specifically, to Native North American cultures.

Key terms that have become integral to Native-centered theories and methodologies include the methodological triad we just referred to: context, a holistic approach to literature (Allen 1983), and tribal specificity or tribal-centered criticism (Armstrong and Blaeser in Armstrong 1993 and Womack 1999). In addition to these, other Indigenous concepts and worldviews that continue to shape and stir the field include the intrinsic power of story and storytelling styles (Momaday 1997), communitism (Weaver 1997), intellectual sovereignty (Warrior 1995), the ethics of caring and interdependence (Whyte and Cuomo 2016), land-based pedagogy and solidarity (Wildcat et al. 2014), or responsibility and ethical engagement (McKegney in Reder and Morra 79). Such interconnected and holistic view of knowledge straddles all fields of life and experience and includes other-than-human perceptions, languages, and needs, all of which must be taken into account.

The compilation of chapters we present in this book respectfully follows the tracks of many inspiring pedagogical anthologies and ongoing critical work. Paula Gunn Allen’s pioneering Studies in American Indian Literature: Critical Essays and Course Designs (1995) continues to be a great source of ideas, activities, and examples. Contributors to this early volume strongly emphasized the need to rely on and teach specific cultural contexts alongside the required literary readings, whether these were part of traditional American Studies survey courses or modules that focused on US ethnic or North American Indian literatures.

Teachers in North American and foreign institutions seeking to incorporate Native American, First Nations, and Indigenous literatures into their curriculum should also consider two essential works which stress such interconnected and Indigenous-centered view of knowledge. These are Linda T. Smith’s Decolonizing Methodologies (1999) and Reder and Morra’s recent compilation of essays Learn, Teach, Challenge. Approaching Indigenous Literatures (2016).

In her groundbreaking book Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (1999), Maōri scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith identifies several decolonizing principles that should guide our research and, by extension, our teaching practice when engaging Indigenous cultures. These are articulated around four main areas: “survival, recovery, development, and self-determination,” all of which aim to validate Indigenous systems of knowledge, to mobilize and heal Indigenous communities, and to transform Western-based research practices around the world (116). Smith’s decolonizing tenets vindicate the inclusion of Indigenous concepts, practices, and methods such as testimonies, storytelling, remembrance, revitalization, representation, reframing, protection, connection, or intervention, ultimately aiming to achieve cultural and socio-economic restitution and political self-determination for all Indigenous peoples around the world.

Deanna Reder and Linda M. Morra’s anthology Learn, Teach, Challenge. Approaching Indigenous Literatures provides a comprehensive view of foundational terms that lay at the roots of contemporary Native American and Indigenous Canadian literary criticism and that are coherently articulated following a Native-centered perspective. This casebook can be of strategic assistance to those lecturers, both veteran and new to the field, ready to engage Native North American literature in their modules and institutions. The anthology contains key essays that have become canonical in the field and new approaches that nicely converse with and complement these classics. The volume is organized around key pedagogical areas such as the importance of one’s positioning (that is, situating yourself as a scholar in relation to this material), self-reflection, commitment, and ethical engagement. It also emphasizes the need to reimagine Native cultures “beyond images and myths” (112), and to consider Indigenous literary perspectives, approaches, and styles. Other relevant areas of interest include ethical criticism, storytelling, alliances, collaboration, or reconciliation.

In addition to Allen, Smith, and Reder and Morra’s efforts, many other works have contributed to these ongoing conversations and continue to provide enlightening food for thought. Among these we would like to mention Maria Battiste’s edited volume Reclaming Indigenous Voice and Vision (2000), Devon Mihesuah’s Indigenizing the Academy (2004), Margaret Kovach’s Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts (2010), Annette Portillos’s essay “Indigenous-centered Pedagogies” (2013), Channette Romero’s “Teaching Native American Literature Responsibly in a Multiethnic Course (2014), or Louie, Poitras, Pratt, Hanson and Ottman’s “Applying Indigenizing Principles of Decolonizing Methodologies in University Classrooms” (2017).

As Louie, Poitras-Pratt, Hanson, and Ottman poignantly state, “the modern university is the epitome of ‘Western’ institutions, having played a key role in the spread of empire and the scientific study and colonization of Indigenous peoples and cultures” (17). Although they refer to Canadian universities, this predicament applies to many academic institutions throughout the Western world, most of which continue to exclude non-Western knowledge and practice from the curriculum.

To counter such potentially distorted representations and colonialist readings in other parts of the world beyond North America, where cultural assumptions, clichés, and misinterpretations can be more frequently encountered, our collective volume Indigenizing the Classroom: Engaging Native American/First Nations Literature and Culture in non-US Settings, presents a strategic selection of critical case studies that set specific texts within cross-cultural pedagogical contexts wherein Native-based methodologies and key concepts are placed at the center of the reading practice. We believe that keeping tribal contexts and specificity upfront is key to guiding students responsibly and ethically through these literary works but we also consider that the conversations these texts and contexts stir, when set in conversation with other major and minor non-Native literary voices, cannot be ignored. These dialogues can enrich global debates on national and local identity, colonialist histories, comparative gender and sexuality, racism, power, environmentalism, or social justice, and our hope is to add more theoretical and practical ideas to these ongoing transnational conversations. We contend that Native American texts bring indigenizing power to non-Native classrooms but teachers also play a key role as decolonizing guides and cross-cultural mediators so that the tribal particularities, interests, political struggles, and cultural perspectives of each individual text are not lost nor appropriated.

This book thus provides a set of critical analyses and practical resources that may enable teachers outside the United States and Canada to incorporate Native North American literature and related cultural and historical texts into their teaching practices and current research interests in a responsible, decolonizing, and creative manner. And, of course, these theoretical and methodological reflections, activities, and resources can also be applied to the teaching of Indigenous literatures in North American classrooms since, as LaLonde argues here, most US colleges and institutions are also a “foreign context” where a majority of non-Native students (and teachers) rely on stereotypical imaginaries and cultural assumptions. The challenging role of teachers and researchers as potential intermediaries and responsible disseminators of “transnational literacy” (Spivak 1992) as well as the adequate reception of Native North American works, contexts, and themes by international or “foreign” readers thus become a primary focus of attention.

The volume strategically opens with Philip Round’s “Pedagogies of Language Sovereignty,” which traces a linguistic map of cultural distinctiveness through the Native Americas. Round’s pedagogical method is articulated around the idea of language sovereignty, an Indigenous-centered approach that can be used by non-Native students in the United States and in other parts of the world. Round’s pedagogies of language sovereignty set traditional language revitalization and use as a key source of cultural and historical identity driving contemporary Native North American literature. This is the case when these literary works are written in autochthonous languages but also when they are conveyed through the settler colonial language, the “enemy’s language” (Harjo and Bird’s term 1997)—an American English that is strongly shaped by Native thought and expression and through its connections to a specific landscape. When this idea is applied to the classroom, Native nations’ linguistic uniqueness “translates into a focus on the Indigenous writer’s use of words in ways that speak to general difference in their communities” (Round). Native works are thus not explored merely on the basis of structure, themes, or political drive. Their specific intellectual traditions and linguistic forms of expression are central to the approach.

If Round’s essay measures the distinctiveness of Native literatures through their linguistic and land-based features, Chris LaLonde’s chapter urgently positions place as a crucial element of Indigenous-centered approaches in the study of Native North American literatures: “place matters.” A teaching strategy he strongly recommends to highlight tribal specificity is to focus on one single Native literary tradition throughout the semester and, with that end in mind, he sets Anishinaabe literary works as an example. Place-based understandings of literature stress the intricate and fundamental ways in which people and place are connected in Native American philosophies and practices. LaLonde contends that the White Earth Reservation, placed between other Anishinaabe reservations, functions as a contact zone of sorts, a connecting space “where multiple forest-types and ecosystems meet and mingle” while Annishinaabe literary texts become another contact zone—“a place where we might unlearn so that we can begin to learn something about White Earth, the people, their literary texts, and indigeneity” (see LaLonde’s chapter in this volume). Furthermore, LaLonde brings our attention to Anishinaabe cultural practices such as trickster-like tactics and effects, storytelling, and performative techniques that can be effectively applied in the classroom. He also explores Vizenor’s Ghost Dance of “continental liberty” (Vizenor 2009), which he presents as a way to maintain cultural specificity, land, resistance, and sovereignty at the center of Native North American literatures when these are engaged as World Literature or in other parts of the world. Like LaLonde, we believe that applying these Indigenous techniques and methodologies “means unlearning the classroom and the academy” (LaLonde in book) and that a valuable tool to do this effectively is to present these texts with pleasure, commitment, and enthusiasm.

Gabriela Jeleńska’s chapter entitled “Buffalo Man” reflects on recent pedagogical experiences she had when teaching traditional Native American myths and tales to her university students in Poland. Through some of her students’ reactions, she discusses the challenges of applying a “tribally informed” approach that is also open to an “empathetic-intuitive response” that allows students to engage the text through personal emotion and pleasure. Her results show that balancing these two methodologies, an Indigenous-centered focus and a personal response, is a fragile and challenging undertaking, for students’ own cultural and moral preconceptions may end up shaping their interpretation of the text. According to her, this may happen even when the specific tribal context has been thoroughly laid out for them because some non-Native readers may choose to resist it. Ultimately, Jeleńska’s classroom activities vindicate the importance of stories to understand our world and other worlds but she also instils caution, for what may work for a group of students in a specific academic institution may not work for another group just a year later.

Gibert and Ortells’ chapters contend that Native American history and culture can effectively be taught in connection with non-Native historical, literary, and audiovisual materials, and that these can also be reconsidered and reinterpreted through Indigenous-centered and tribal-specific readings. Western accounts written by settler colonizers can also be decolonized and even indigenized.

Teresa Gibert specifically discusses the teaching of Pocahontas, also known as Matoaka, Amonute, Rebecca Rolfe, and Lady Rebecca, in American Studies modules in a Spanish university. She asks her students to examine the Pocahontas story according to a variety of critical interpretations, written, and also visual formats that aim to challenge her construction as a “mythical figure.” As Pocahontas never recorded her own story, Gibert recommends the use of a wide spectrum of historical and artistic documents and particularly favors the website The Pocahontas Archive. This vast online archive gathers a variety of narrative voices and historical perspectives through which we can rethink our understanding of this historical character while connecting disciplines such as literature, history, film, and art in a revisionist manner and within virtual learning environments.

Elena Ortells’ chapter explores a well-known colonial gender, captivity narratives, and strongly takes into account the specific tribal practices and worldviews of the Native cultures depicted in these texts. Within this genre, she is particularly interested in the stories of female captives that chose to “go native” after experiencing physical, emotional, and cultural displacement. Despite their traumatic experiences, they were able to adapt to the Indigenous societies they lived with and learned to renegotiate the concepts of identity and home.

Among the various captivity narratives written by female captives, Ortells recommends using the Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison. According to Ortells, Mrs. Jemison managed to successfully reconfigure her domestic practices, which were based on a rather Western understanding of home and female domesticity, and gave a precise account of Seneca customs and their use of land—one that questioned dominant visions of Native American practices at the time and that subverted colonial representations of both Native and settler women.

In her chapter “Teaching Native American Literature in Argentina,” Márgara Averbach focuses on another pedagogical challenge: What do we do when our students’ level of English is not adequate and, as a result, when these literary and cultural materials have to be presented through translation into other languages? Averbach’s approach is to consider Native texts’ hybrid linguistic qualities since they actively “reinvent the enemy’s language” and the enemy’s literary forms to express their own worldviews (Harjo and Bird 1997). To that end, Averbach (who often translates most Native North American texts used in her classes into Spanish) illustrates her teaching practice through the analysis of a poem by Simon Ortiz, “Speaking” (“Hablar”), and reflects on the pitfalls and possibilities offered by texts taught in translation.

Dolores Miralles-Alberola’s chapter “Native American Children’s Literature in the English Language Education Classroom” reminds us that Native American literary works can be strategically deployed in the teaching of English as a Foreign Language and as a compelling way to develop empathy, critical thought, and intercultural competence. She argues that Native American literary works could be introduced in the classroom in early educational levels as Native American children’s literature encompasses a wide range of traditions and genres which include oral traditional myths and tales, and also contemporary works such as picture books, fictional tales, memoirs, historical accounts, and rhymes written by well-known contemporary Indigenous authors. In her chapter, she explores a selection of works by Joy Harjo, Simon Ortiz, Nicola Campbell, or Lucy Tapahonso, among others. She offers some strategies and resources that can be meaningfully applied by elementary and middle school teachers in foreign settings, helping them to engage these texts with respect, commitment, and pleasure.

Like Gibert’s and Ortells’, Vicent Cucarella-Ramon’s contribution to this volume explores alternative forms of representation in non-Native literary works that are, however, Indigenous-centered. In his analysis of Black Canadian author Wayde Compton’s short story collection The Outer Harbour, Cucarella-Ramon brings the focus back to the idea of periphery, rather than center, as a meaningful space of connection and resistance that should not be dismissed. Transethnic readings and alliances are possible in such peripheral spaces which challenge not only Western but also Afrocentric paradigms. Like LaLonde’s Anishinaabe approach, Compton’s Afroperipheralism also envisions the literary text as a contact zone where fruitful alliances between Indigenous and Black Canadians can be forged, while an interrelated history of colonial oppression and silencing can be acknowledged and re-centered.

The volume closes with Ingrid Wendt’s creative and personal approach to the Cherokee poetry of her late husband Ralph Salisbury. Wendt’s chapter moves Indigenous-centered pedagogies from local to global concerns through her discussion of Salisbury’s poems. Through her fresh, honest, and engaging style, Wendt, who is a poet herself, explores several ways through which the teaching of Native North American literature can indigenize our classrooms using poetry as a springboard. Moreover, Wendt identifies many conflicting situations in Salisbury’s poems that could lead students to critically explore similar experiences and processes in their own local settings. To that end, she discusses the effects of ethnic violence and racism, the importance of speaking up when facing social injustice rather than becoming complicit with it, the challenges of navigating a cross-cultural identity, our current climate crisis, and the expression of simple human gratitude and cross-cultural dialogue—core practices which are not easily tackled in the Trump/post-Trump era and which must be urgently addressed not only in North America but in many other countries around the world as well.

The classroom space is, as LaLonde pointed out, a contact zone of sorts, with asymmetrical relations constantly being negotiated between teachers and students, between readers and texts. Classrooms can also foster the growth of dynamic, globally-minded and empathetic learning communities, and one way to create such an environment is to place Indigenous-authored texts and methodologies at the center of the conversation, radically changing the way we (readers in other parts of the world) think about the world. Applying Indigenous-centered methods and tribal-specific philosophies and tactics can be transformational, not just for Indigenous communities around the world but also for many non-Native students in non-Native settings. As Gayatri Spivak stressed in her Death of a Discipline, helping students to develop “transnational literacy” which translates into an awareness of and respect for the world’s cultural and literary diversity, and our own collective responsibility in disseminating and protecting it, must lay at the core of our pedagogical efforts (see also Chris LaLonde’s chapter). Devon Mihesuah and Angela Cavender Wilson further emphasize this idea by stressing that:

the academy is worth Indigenizing because something productive will happen as a consequence. Perhaps as teachers we can facilitate what bell hooks refers to as “education as the practice of freedom.” Perhaps we might engage in an educational dynamic with students that is liberatory, not only for the oppressed but also for the oppressors. Perhaps as scholars we can conduct research that has a beneficial impact on humanity in general, as well as on our Indigenous peoples. Perhaps the scholarship we produce might be influential not only among our ivory tower peers, but also within the dominant society. Perhaps our activism and persistence within the academy might also redefine the institution from an agent of colonialism to a center of decolonization. (5)

In this respect, even captivity narratives, historical accounts by non-Native chroniclers, contemporary Black Canadian fiction, or children’s literature can be indigenized and strategically used as allied texts in our teaching of Native North American literature, culture and history. As Muskogee Creek poet laureate Joy Harjo poignantly states in her dialogical poem “Advice for Countries, Advanced, Developing and Falling”: “There will be no balance without all voices present in the power circle” (80). In education, classrooms are our power circle.

Works Cited

Aboriginal Worldviews and Perspectives in the Classroom. Moving Forward. British Columbia Ministry of Education. Queen’s Printer Publishing Services, 2015.

Allen, Chadwick. Trans-Indigenous: Methodologies for global Native literary studies. University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Allen, Paula Gunn. Studies in American Indian Literature: Critical Essays and Course Designs. Modern Language Association (1983) 1995.

Armstrong, Jeannette, ed. Looking at the Words of Our People: First Nations Analysis of Literature. Theytus, 1993.

Battiste, Marie. Decolonizing Education: Nourishing the Learning Spirit. University of British Columbia Press, 2017.

Harjo, Joy, Gloria Bird, and Patricia Blanco, eds. Reinventing the Enemy’s Language: Contemporary Native Women’s Writing of North America. WW Norton & Company, 1997.

Harjo, Joy. An American Sunrise. Norton, 2019.

Kovach, Margaret. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. University of Toronto Press, 2010.

LaRocque, Emma. “Teaching Aboriginal Literature: The Discourse of Margins and Mainstreams.” In Reder and Morra, 2016. 55-72.

Louie, Dustin William, et al. “Applying Indigenizing principles of decolonizing methodologies in university classrooms.” Canadian Journal of Higher Education/Revue canadienne d’enseignement supérieur 47.3 (2017): 16-33. https://doi.org/10.7202/1043236ar

McKegney, Sam. “Strategies for Ethical Engagement: An Open Letter Concerning Non-Native Scholars of Native Literatures.” In Reder and Morra, 2016. 79-88.

Mihesuah, Devon Abbott, and Angela Cavender Wilson, eds. Indigenizing the Academy: Transforming Scholarship and Empowering Communities. University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

Momaday, N. Scott. “The Man Made of Words.” The Man Made of Words: Essays, Stories, Passages. Macmillan, 1998.

Portillo, Annette. “Indigenous-Centered Pedagogies: Strategies for Teaching Native American Literature and Culture.” The CEA Forum. Winter/Spring (2013): 155-178.

Reder, Deanna, and Linda M. Morra, eds. Learn, Teach, Challenge: Approaching Indigenous Literatures. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books. University of Otago Press, 2013 (1999).

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. Death of a Discipline. Columbia University Press, 2003.

Vizenor, Gerald. Native Liberty: Natural Reason and Cultural Survivance. University of Nebraska Press, 2009

Warrior, Robert Allen. Tribal Secrets. Recovering American Indian Intellectual Traditions. University of Minnesota Press, 1995.

Weaver, Jace. That the People Might Live: Native American Literatures and Native American Community. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Wildcat, Matthew, et al. “Learning from the Land: Indigenous Land-Based Pedagogy and Decolonization.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3.3 (2014): 1-15.

Whyte, Kyle Powys, and Chris J. Cuomo. “Ethics of Caring in Environmental Ethics.” The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Ethics, 2016. 234.

Womack, Craig. Red on Red. Native American Literary Separatism. University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

1 We would like to express our gratitude to the Conselleria d’Innovació, Universitats, Ciència i Societat Digital (Generalitat Valenciana) for generously providing the research funds that enabled the writing of this chapter and the edition of the volume as a whole (Research Project: “Las literaturas (trans)étnicas norteamericanas en un contexto global: representaciones, transformaciones y resistencias.” Ref. GV/2019/114).

Pedagogies of Language Sovereignty

Phillip H. Round

University of Iowa

As a teacher of Native American literature at a US university, I have become very familiar with the challenges posed by the necessity to offer that literature within a context that is true to the complex relations that exist between it and federal Indian policy, individual tribal communities’ cultural and social practices, and the history of its place in the broader canon of American literature. Those problems might at first seem to be insurmountable in the context of European university curricula. But, in reality, my US students are often very unfamiliar with their own nation’s history and are in need of a kind of remediation that is no more demanding than the work non-US teachers must put into their own pedagogical practices when they offer their students Native American literary texts.

As a response to this situation, I offer an approach to teaching Native American literatures in non-US settings that I call a “pedagogy of language sovereignty.” Simply put, this teaching method puts the struggle of Native nations to revive and maintain their languages front and center in the classroom. For our purposes, “language sovereignty” may be defined as an Indigenous community’s use of its traditional language as a tool “for stressing its cultural and historical uniqueness,” as well as their “cultural distinctness from nonindigenous governments” (Viatori and Ushigua 7). Having taught for a few semesters at universities in Portugal and Spain, I have some experience in translating the cultural contexts of “American” literary works for European students. When I have turned my attention to the doubly difficult task of contextualizing Native literature (a body of texts and orature traditions that many Native theorists resist calling “American” at all), I seized upon this formulation as a response to the question “How one would teach Native American Literature as World Literature?”

Ever since Goethe announced that “the era of world literature is at hand, and everyone must contribute to accelerating it,” there has been a corresponding commitment “to acknowledge and validate occluded regions of the non-Western world as unique literary and historical spaces that contribute to the whole” (Conversations 133). This recognition has, in turn, “necessitated an altogether different framework for theorizing concepts such as language, nation, and masterpieces” (“World Literature” 1). This is laudable goal, and I can see why thinking about Native literature in this way might be helpful. Still, I have some concerns about applying this perspective to Native literature. Like the term “World Music,” World Literature is not a fixed category. By applying it to Native texts, its lack of definitiveness could lead us into some pretty unsavory places—cultural appropriation, generalization, homogenization. Indeed, contemporary Native American critics like Jace Weaver have forcefully argued that “Native American literary output [is] separate and distinct from other national literatures’ and “proceeds from different assumptions and embodies different values from American literature” (15).

Therefore, in order to present what I think is a more Native nation-centered praxis as a ground for our foray into this world perspective, I propose a language sovereignty-oriented pedagogy that is decolonizing in a number of ways. For one thing, as Indigenous language educator Belinda Daniels of the Sturgeon Lake First Nations in Canada has recently observed, “In order for a nation to exist, the Nehiyawak [Sturgeon Lake First Nations], for example, require five elements: land, culture, governance, people and a language.”1 In fact, a Native community’s pursuit of language revitalization, intertwines with the other four elements of cultural survival Daniels cites here—language embodies culture, enunciates governance, knits people together. My pedagogical ideas thus derive from the power of language to circulate through and constitute communities. In the classroom, this translates into a focus on the indigenous writer’s use of words in ways that speak to generational differences in their communities, address political shifts both within and without their tribes, and forge continuing links between their words and their homelands. Language is more than a medium of expression for these writers; it is a practice. It is a cultural technique that continually unites kinship groups across time, mobilizes time-honored ceremonial and storytelling practices in new ways to meet new political obstacles, and in many cases is viewed as an organic outgrowth of an indigenous homeland, grounding the speaker, writer, and listener in what the ethnographer Keith Basso has called “the wisdom of places.”2

Thus, the first step in teaching Native literature from a language sovereignty perspective is to present students with a linguistic map of the US. This one, produced by the linguist Ives Goddard of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, vividly illustrates the many different kinds of languages that are at work in Indian Country.

Before European contact with North America, more than 300 separate languages were being spoken in this part of the Western Hemisphere. As ethnolinguist, Marianne Mithun explains, these languages were “mutually unintelligible … and differ in fascinating ways not only from the better-known languages of Europe and Asia, but also among themselves” (1). Whereas European languages can be categorized into only three distinct “families” (Indo-European, Finno-Urgic, and Basque), there are about fifty Indian language families in North America, none written in alphabetic form.

Among this linguistic diversity, several factors stand out as perhaps influencing the way Native writers approach writing in English. Words, for example, are treated differently in the polysynthetic languages of North America. In Yupik, a language spoken in western Alaska, the word kaipiallrulliniuk is translated into the English phrase “the two of them were apparently really hungry” (Mithun 39). Some North American languages like Mohawk contains only nine consonants, while Tlingit, an Athabaskan language, contains forty-five. In addition to diction and phonological differences, Native languages exhibit (as perhaps do all languages) some relationship to their physical environment.3 If one looks at the Goddard map and locates the landscape in which Yupik is spoken, it makes sense that this language is filled with terms like caginraq (“skin or pelt of caribou taken just after the long winter hair has been shed in the spring”), a term whose specificity is born of generations of experience in Alaskan ecosystems (Mithun 37).

Map by Ives Goddard. “Native Languages and Language Families.” Compiled for Languages, vol. 17 of the Handbook of North American Indians (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1996).4

By examining this map, our students might also begin to imagine some other relationships that obtain between the land and language. Putting aside for a moment those many tribes that were removed from their homelands after the Indian Removal Act of 1830,5 they might look at how the languages of the Athabaskan Family are distributed across North America. The swirl of olive color that denotes Athabaskan—split as it is between the sub-arctic and the Great Basin of the US—suggests another important element of language, the fact that it also maps migrations and movements of peoples.

In order to ground these somewhat speculative observations in the real-world work of a Native poet, let’s examine a writer whose community still resides in part of its original homeland and whose language speaks of that land. Jeanette Armstrong is Okanagan. Okanagan is spoken in southern British Columbia in Canada and in north central Washington in the US (Mithun 492). It is a language known to its speakers as Nsilxin, and is perhaps spoken by 500 to 1000 speakers. Armstrong is of the “opinion that Okanagan, my original language, constitutes the most significant influence on my writing in English” (178). She also believes strongly that “the language spoken by the land which is interpreted by the Okanagan into words, carries parts of its ongoing reality” (178). “In this sense,” Armstrong writes, “all indigenous peoples’ languages are generated by a precise geography and arise from it” (178). In addition to the “landed” nature of indigenous languages that lie behind Native writer’s English literary works, Armstrong notes a profound difference in the way that nouns and images are understood and employed in Okanagan.

Using the example of the English word, dog, Armstrong explains, “when you say the Okanagan word for dog (kekwep), you don’t ‘see’ a dog image, you summon an experience of little furred life” (190). This is because the two syllables in the word suggest a combination of “a happening and a sprouting profusely (fur).” Armstrong thus observes that “speaking the Okanagan word for dog is an experience” (190). In Okanagan, the word is more a verb than a noun, and when Armstrong employs this understanding to her English language works, “[she] attempt[s] to construct a similar sense of movement and rhythm through sound patterns” (192). In the poem “Winds,” she demonstrates these practices:

The influence of the Okanagan language on Armstrong poetry does not stop with these morphological and syntactic elements. The way English is spoken on the Okanagan Reserve is considered a kind of dialect of the English language that, in its various forms, is known in Indian Country as “Rez English.” Like Armstrong’s poetic lines in English, “Okanagan Rez English has a structured quality semantically and syntactically closer to the way the Okanagan language is arranged,” and Armstrong argues that “Rez English from any part of the country, if examined, will display the sound and syntax pattern of the area.” Armstrong explains how this might work in the following sentences:

Trevor walked often to the spring to think and to be alone. Rez English would be more comfortable with a structure like this: Trevor’s always walking to the spring for thinking and being alone. The Rez style creates a semantic difference that allows for a fluid movement between past, present, and future. (193)

In both her Rez English usage and her ethnopoetic approximations of Okanagan verbal arts structures, Jeanette Armstrong feels her “writing in English is a continual battle against the rigidity in English” (194).

If we turn our attention to a very different landscape and language located on the southern border of the US, we find the Tohono O’odham Nation and the poetry of tribal member and linguist Ofelia Zepeda. Two of Zepeda’s poetry collections, Ocean Power (1995), and Jewed I Hoi (2005), are bilingual O’odham/English gatherings of verse. Many of Zepeda’s poems “originated in the O’odham language,” and when she offers an English counterpart, she cautions the reader that “they are not translations of the O’odham into English” (Jewed 7). As Zepeda explains in the Introduction to Jewed I Hoi, “Written O’Odham is a relatively new phenomenon,” and employs the orthography developed in the middle of the twentieth century by Albert Alvarez and Kenneth Hale.” Sanctioned by the O’odham Nation, “it is the writing system most commonly used for classroom teaching. Literacy in the O’Odham language is accessible only to young people in schools that offer O’odham language classes, and to adults who make the choice of becoming literate” (7-8). Thus Zepeda’s O’odham language poems stand in a unique relation to the verbal traditions that lie behind them. A case in point is her use of traditional songs to bring the rain to her desert homeland as a jumping off point for these two versions of “Cloud Song:”

Ce: daghim ‘o ‘ab wu: sañhim.

To:tahim ‘o ‘ab wu: sañhim.

Cuckuhim ‘o ‘ab him.

Wepeghim ‘o ‘abai him.

Greenly they emerge. In colors of blue they emerge.

Whitely they emerge.

In colors of black they are coming.

Reddening they are right here.

As in Armstrong’s verse, the O’odham language exerts a special morphological influence on its English counterpart. The repetitions of word ending auxiliaries common in O’odham must be abandoned in the English version to emphasize what is the “experiential” nature of nouns in the vernacular.6