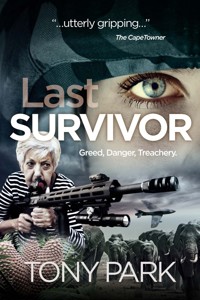

7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: AJP

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Only a bunch of heavily armed gardeners can save the world's most valuable plant.

A priceless plant, a rare African cycad thought to be extinct and prized by collectors, has been discovered, then stolen.

Joanne Flack, widowed and broke, is the prime suspect for the crime. While supposedly hiding out in London she single-handedly foils a terrorist plot, killing a lone-wolf gunman.

Former mercenary turned CIA contractor, Sonja Kurtz, uncovers a link between the missing plant and the terrorist who tried to kill Joanne. The US Government thinks that if it can find the missing cycad it can foil an attack to rival 9-11.

Hot on Joanne’s trail is retired US Fisheries and Wildlife Department special agent Rod Cavanagh who knows his plants and knows his target – he’s her former lover.

Joanne is a member of the Pretoria Cycad and Firearms Appreciation Society. She, Sonja and Rod enlist the help of this group of ageing gardeners and gun nuts to find a plant worth a fortune and the traitor in their midst who is willing to kill for it.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

About Last Survivor

Only a bunch of heavily armed gardeners can save the world's most valuable plant.

A priceless plant, a rare African cycad thought to be extinct and prized by collectors, has been discovered, then stolen.

Joanne Flack, widowed and broke, is the prime suspect for the crime. While supposedly hiding out in London she single-handedly foils a terrorist plot, killing a lone-wolf gunman.

Former mercenary turned CIA contractor, Sonja Kurtz, uncovers a link between the missing plant and the terrorist who tried to kill Joanne. The US Government thinks that if it can find the missing cycad it can foil an attack to rival 9-11.

Hot on Joanne’s trail is retired US Fisheries and Wildlife Department special agent Rod Cavanagh who knows his plants and knows his target – he’s her former lover.

Joanne is a member of the Pretoria Cycad and Firearms Appreciation Society. She, Sonja and Rod enlist the help of this group of ageing gardeners and gun nuts to find a plant worth a fortune and the traitor in their midst who is willing to kill for it.

Contents

For Nicola

Prologue

London, England

He was doomed. The last of his species to have lived in the wild, his extinction was guaranteed. The question was not if his kind would disappear from the face of the earth, but when.

With no females left alive in their natural habitat or in captivity there was no chance of natural reproduction.

The luckier of his ancestors had been stolen from Africa and shipped to foreign lands. In years gone by this had been done by supposedly well-meaning colonialists, who had displayed their captured specimens for generations of enchanted aficionados to gawk at.

Today it was illegal to take them from the wild, but that didn’t stop the wealthy from breaking the law. Impoverished poachers were paid by middlemen to risk imprisonment, perhaps even death at the hand of an armed ranger, to satisfy the desire of proud rich people to flaunt their wealth and status by showing off something rare.

But he was now beyond rare; he was critically endangered, extinct in the wild.

His less fortunate forebears had been butchered for use in traditional medicine, hacked to pieces, ground into potions whose efficacy was spurious, at best. But worse, he was a victim of his rarity; he had been taken to serve the basest of emotions.

Pride.

Greed.

Vanity.

Envy.

These were the sins that had spelled a death sentence for a species that predated the dinosaurs and had once been seen across much of the earth’s surface. Of course, scientists were looking for ways to artificially continue his existence, but it would never be the same.

He had come from a forested hill in Zululand, and while it had sometimes been misty and cool it had never been as cold as it was here, in England. His enclosure protected him from the worst of the elements and that was just as well, for if he had been left to face the harsh northern winter in the outdoors he would surely have died long ago.

So he sat, all alone, under a cold grey sky. Fertile – he had shown his captors he could produce, like some slave from bygone times being exposed and inspected by those who would use him as breeding stock – but he was nonetheless condemned.

The crime of it, Joanne Flack thought as she stared lovingly at him, was that so few people in the world even knew about him, let alone cared.

Joanne looked around, making sure no one was watching, and then reached out and ever so gently stroked one of the plant’s spiky green leaves.

‘Hello, Woody, my old friend. I might have some good news for you.’

Chapter 1

Pretoria, South Africa

Jacqueline Smit banged her gavel on the table. ‘I call this meeting of the Pretoria Cycad and Firearms Appreciation Society to order. Are there any apologies?’

Thunder rumbled outside like a distant artillery barrage, but the lightning strike that followed was close, as loud as a direct hit. Thandi Ngwenya dropped her knitting and Jacqueline frowned.

A hadada ibis gave its drawn-out, eponymous call as it took off in fright from the water feature just outside the back-room office of the garden centre where they were meeting, sitting around an eight-seat boardroom table.

‘Sorry, my Queen,’ Thandi said to Jacqueline as she reached to retrieve the tiny jersey she was knitting for her third grandchild. Thandi’s back ached when she bent over and SS, Stephen Stoke, who proclaimed himself 100 per cent Boer despite the shame of the Christian and surnames his English-speaking father had bestowed on him, dropped to one knee, creakily, and retrieved it for her. SS was quick to criticise the African National Congress government of South Africa and Thandi had sensed he had been distinctly uncomfortable with her, initially, as the first black person to join their society, but over time they had become friends and both, she thought, had learned to leave some of their prejudices where they belonged: in the past. ‘Thank you, SS.’

SS smiled. ‘Pleasure, Thandi.’

‘Queen’ Jacqueline Smit, as she was known to the other members, gave Thandi a curt nod and banged her gavel again, as loud and as fast as a double tap from a Glock. Her beehive hairdo, piled appropriately like a crown on her head, shook slightly.

Charles Borg, a white-haired old South African of Viking stock, sat to attention in his chair and folded his arms. ‘Apart from the obvious apology?’

The ticking of the wall clock became audible. Laurel looked to Baye, who rolled her eyes.

‘Has Joanne not officially resigned yet, or been given the chop?’ Sandy Burrell asked.

Charles leaned over and put one hand on the back of Sandy’s wheelchair. ‘Not yet. She took off to London while you were in hospital. How did it go, by the way?’

‘Well my spinal cord isn’t going to fix itself, of course, but the treatment was good. Basically, I’m still fucked.’

Jacqueline cleared her throat. ‘Language.’

‘All right, all right,’ Charles said. ‘We have one apology, Mrs Joanne Flack.’

‘Thank you,’ Jacqueline said. ‘You’ve all read the minutes of the last meeting, I take it, so there is no need for me to go through them?’

SS leaned back in his chair, the buttons of his farmer’s two-tone khaki and blue work shirt threatening to open fire as the material stretched tight across his spreading belly. ‘Ag, enough of this what-what-what. I move the minutes be accepted.’

A quick show of hands confirmed it.

Thandi looked around the room at her friends, because despite their occasional differences and outbursts, and instances of latent racism, they were her friends. Sandy frowned; SS harrumphed; Laurel Covey inspected her latest manicure for non-existent signs of imperfection; and Baye Pigors, at sixty-seven still as lithe as a leopard in Lorna Jane activewear, regarded Jacqueline through narrowed golden eyes. Baye’s hair, long, dark and lustrous, was pulled back from her olive-skinned face in a plait. She taught Pilates for the more-mature to while away her spare hours and to keep herself in shape; her regime was working, Thandi mused with not a little envy.

Charles sat up. ‘Very well, I’ll speak to the elephant in the room …’

‘Who are you calling an elephant?’ Laurel asked, finally tiring of looking for her reflection in her fingernails.

Jacqueline frowned and Thandi sighed. Laurel was the prettiest woman in the room, and had been mistaken more than once, she was keen on reminding them, for being twenty years younger than her sixty-five years. Thandi touched her gently on the arm. ‘It’s a figure of speech, dear, it means the big thing everyone is scared of, and knows is there, but does not want to address.’

Charles, handsome and debonair as ever in his sports coat and cravat, cleared his throat. ‘I move that Joanne Flack be hereby … what’s the word, excommunicated, terminated?’

Jacqueline clenched her teeth and drew her lips back from them. ‘Expelled?’

Typical ex-teacher, Thandi thought as she started her knitting again. She wasn’t being rude – the others knew she was able to listen to everything they said while she knitted, and it calmed her when she felt anxious. Like now. These people were messing with words. In her day, in the training camp in Mozambique, they’d known what to do with traitors.

‘What do you think, Thandi?’ SS asked. ‘Expelled?’

She looked up from her knitting. ‘I was thinking that at one time in my life, if someone betrayed the cause they would be killed. The ANC would burn them – with a necklace, you know, a tyre filled with petrol – but we Zimbabweans would simply shoot them.’

SS raised his eyebrows. ‘Sheesh, man, you think we should shoot Joanne? This is not the old days.’

They were all looking at her now, as if she was the odd one out. They were no different from her. Her eyes lingered on each of her friends for a second. Charles Borg had been a South African Defence Force helicopter pilot under the old apartheid regime and had served in Namibia and Angola and, for a time, in Thandi’s native Zimbabwe, flying for the Rhodesians. Ironically, Thandi’s second husband – the first love of her life – had been a white man who had also flown choppers in Rhodesia. Charles had, it turned out, flown with her husband George for a short while in the same squadron. Thandi and George had been forced to keep their love a secret during the Bush War and had been estranged for many years, finally reuniting not long before dear George died of a heart attack.

SS was a former Recce-Commando, a member of South Africa’s elite special forces; Jacqueline, her Majesty the Queen, had famously shot and killed a man who’d tried to hijack her car; Joanne had grown up on a farm in Zimbabwe, then Rhodesia, and had shot two Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army terrorists, Thandi’s people, during an attack on her family’s property. Laurel, once the wife of a Zululand cane farmer, had shot dead a thief during a farm robbery; and Baye Pigors, a banker’s widow from Johannesburg’s expensive Houghton Estate, had moved to Tel Aviv in 1972 after leaving school to study and found herself serving in the Israeli Army during the Yom Kippur War in 1973 before moving back to South Africa. They had all once been soldiers or involved in gunfights, living for a time on a diet of adrenaline and fear, but today they looked forward to their cycad society meetings and pensioners’ discount Tuesdays at Builders Warehouse.

Even dear Sandy, the youngest of them at fifty-five, had put a bullet in a home invader’s leg when he’d tried to threaten her into giving over the PIN for her Visa card – he had dropped his guard, thinking her disability, the result of a motor vehicle accident, made her helpless, and she had pulled the CZ-83 from the side pocket of her wheelchair and dropped him. She had sat there, keeping him covered, until the police tactical unit arrived at her home in Centurion.

Charles scoffed. ‘Well, Thandi? It’s not the liberation war now so we won’t let you burn or shoot anyone to death as a punishment for betrayal.’

‘No,’ she tutted in reply. ‘I wouldn’t dream of it, and nor do I think Joanne should be expelled, or excommunicated, or sanctioned. At least not until we’ve heard from her.’

‘Tell me exactly what I’ve missed over the last couple of weeks,’ Sandy said. ‘I want to hear it from the chair, not via the rumour mill.’

Queen Jacqueline looked down over the top of her horn-rimmed eyeglasses. ‘Joanne, as treasurer, had not only the bank account log-in details, but also the keys to the storeroom.’

‘Yes,’ Sandy said. ‘And …’

‘And as you would have heard from the others already, the police brought us a fine specimen of Encephalartos woodii, a female plant no less, and –’

Sandy broke in: ‘Yes, I could hardly believe it when Joanne told us she’d discovered a female woodii, but to then find out it was stolen, not once but twice, is incredible. That plant must be worth …’

‘A fortune, yes,’ Jacqueline continued. ‘The police gave it to us for safekeeping after they caught two men with it at a random roadblock.’

Sandy shook her head. ‘This is just too astonishing for words. How did the cops even know it was a female woodii? I think we can agree it’s unlikely they’d have realised it’s the only one of its kind in the world, so rare no living human had ever even seen one until Joanne and you lot clapped eyes on it.’

Jacqueline held up a hand. ‘If you will allow me to continue …’

Even Sandy, who was never afraid to speak out, had to bow to Jacqueline’s typical forcefulness. She gave a submissive nod.

‘The criminals,’ the Queen continued, ‘had it in the boot of their car. The fact that they rather foolishly tried to run from the police told the cops that the plant was worth something. The detective at the station –’

‘My son-in-law,’ Laurel interrupted, sitting straighter in her chair and beaming proudly.

‘Yes, Laurel’s son-in-law, James, asked Laurel and me to identify it. Needless to say we were shocked when we realised what it was. James later asked, begged, Laurel to bring it to us for safekeeping when she told him what it was – he was worried that once word got out about its true worth it would disappear from his evidence locker. Isn’t that right, Laurel?’

Laurel nodded. ‘Yes, shame, the police don’t even trust one another. Poor James did actually beg me to look after the woodii. And this was obviously the same female woodii that Joanne had discovered in the garden of Prince Whatshisname?’

‘I doubt there are two female woodiis,’ Charles said patiently to Laurel, ‘so, yes, this plant was first stolen from the cycad garden on Prince Faisal al Sabah’s private game reserve, near Hoedspruit, and then stolen again from our storeroom after the police entrusted it to us.’

‘But how can we be sure Joanne took it?’ Sandy asked.

Jacqueline pursed her lips. ‘Well, we can’t, but you have to admit, the evidence is fairly damning. Joanne, as you know, worked for the prince part-time as his consultant horti-culturalist, and knew of the theft from the reserve. After the plant was re-discovered and left with us, Joanne flew out to London to visit her daughter, and when I next checked the lock-up, two days after her departure, the woodii was gone and our bank account had been emptied. Since then none of us have heard from her, despite leaving repeated voicemail and email messages.’

Sandy nodded, frowning. ‘Yes, I tried as well. Nothing. And how come none of this has made the newspapers?’

‘These oil-rich Arabs,’ Baye said, unable to hide her disdain, ‘they have enough money to buy anyone, anything, even the silence of the police and the media.’

‘The theory,’ Thandi said to Sandy, ‘is that Joanne took the cycad and the money with her to the UK. She told me before she left that her son-in-law had lost his job and the family are in debt up to their eyeballs. They had already paid for her ticket to come visit before the young man was sacked.’

SS nodded. ‘I’m afraid to say Joanne asked me for a loan a few weeks ago. Shame, the poor thing is in trouble. I gathered that the money her daughter used to send her from the UK had dried up.’

Charles leaned forward, hands on the desktop. ‘Laurel, did you ask James to open a docket to investigate the theft from our premises?’

Laurel looked to Jacqueline, clearly bewildered. ‘Should I have?’

Jacqueline frowned. ‘This matter is most concerning. One of the things I wanted to discuss here today is what steps we should take next – if it is indeed appropriate to call in the authorities.’

‘“Appropriate to call in the authorities”?’ SS slapped the table. ‘Our bank balance, thirty-something thousand ronts –’

Thandi lowered her knitting and smiled to herself at Stephen’s old-fashioned pronunciation of the word ‘rand’ – the man lived in another era, one he would have termed ‘the good old days’. ‘Thirty-two thousand, six hundred and fifty-five rand and twenty cents.’

‘Whatever,’ SS said, ‘has been stolen, along with a cycad we were supposed to care for until the offenders were dealt with by the courts … I’d say it was time to call in the bladdy police, yes, Jacqueline, especially as this bladdy cycad is worth a king’s ransom.’

Jacqueline glared at him. ‘Language.’

‘Now, now, Stephen,’ Charles said. ‘Like Thandi says, I think we need to give Joanne a chance to explain before we go getting the police involved.’

‘But she’s taken the money and the cycad, Charles, you buffoon,’ Sandy said.

Charles rolled his eyes. Sandy’s abrasiveness was well known, but she seemed to filter her words even less when talking to Charles. Thandi wondered why Charles put up with her barbs. They bickered like an old married couple sometimes.

Baye leaned back in her chair, one long, lycra-clad leg crossed over the other. ‘That Arab prince Joanne worked for would have cut off her hands by now if he’d caught her stealing his cycad. Clearly she didn’t steal the female woodii from her employer in the first place, unless of course she paid the guys who the police arrested to transport it for her and then had to steal it a second time – from us.’ She tilted her head, lifting her nose as if she had just detected a whiff of something unpleasant. ‘It wouldn’t be the first time Joanne dudded someone who trusted her.’

‘I say call the police,’ Sandy said.

Thandi placed the little jersey back in her knitting basket. That very act made some of the others look her way.

‘Comrades …’ SS looked heavenwards, as he always did when Thandi addressed them by that name. She liked using the word solely for his reaction. ‘Comrades, now is not the time for burning necklaces, excommunication or amputation. We must find out what has happened to Joanne. I think she will return to Africa. Joanne told me more than once that she could not bear living in England, or Australia, or anywhere outside of this continent. She is a child of our blood-red soil, and, besides, thirty-two thousand, six hundred and fifty-five rand will not last long in England, particularly the way Joanne drinks.’

SS snorted. Queen Jacqueline frowned. Laurel had resumed her inspection of her perfect nails.

‘You don’t think Joanne stole the cycad?’ Sandy asked.

Thandi shrugged. ‘I’m saying something doesn’t add up. Joanne was investigated for smuggling back in the nineties, you remember?’

SS nodded. ‘I do. She was acquitted, though her husband, rest his soul, was clearly guilty, shot dead by an undercover American G-man.’

‘Exactly,’ Thandi said. ‘Even if Joanne was involved she was able to expertly cover her tracks. Stealing a cycad from under our noses, from our storeroom, is not the style of an accomplished poacher. It’s too obvious. If she had wanted to steal the female woodii she could have taken it from the Kuwaiti’s garden before anyone, including the prince, even knew what it was. Remember, it was she who alerted us to her discovery of the rarest plant in the whole world.’

Laurel had taken to her nail with a file, but now she looked up, at Thandi. ‘So, like, what must we do, Thands?’

Dear Laurel, Thandi thought. If it wasn’t for her extensive knowledge of cycads she would think the woman a halfwit. ‘We must investigate, Laurel.’

‘What are we now,’ SS scoffed, ‘the number one old ladies’ private investigation agency, headed by our own Mama Ngwenya?’

Thandi ignored the flippancy. ‘But we must find Joanne and, if we cannot find her, we must ascertain what she was doing before she left South Africa, who she met with, what she was planning.’

‘What about the son of the king of Arabia or whatever, Prince Sisal?’ Laurel asked.

‘His name is Faisal,’ Charles said patiently, and turned to Sandy. ‘Joanne told us all about her work for him while you were in hospital. Faisal’s a Kuwaiti prince, a minor member of the Al Sabah family, busy building his own private game lodge near Hoedspruit. Joanne had some work advising on the landscaping. The prince is one of us, apparently.’

‘You’re suffering from old man’s disease, Charles, you silly old fool,’ Sandy said. ‘You forget I was here when Joanne told us about her work for the prince and how he’d already had an Encephalartos hirsutus stolen from his garden. So this female woodii is the second valuable cycad he’s lost. And what do you mean, he’s one of us?’

‘He’s a gun nut and a cycad fancier,’ Charles said quietly, somewhat chastised.

Jacqueline weighed in: ‘Come to think of it, we should invite him to join the society as we need his subscription. He’s a hunter – the game lodge is primarily there to stock his private trophy room, apparently.’

Sandy frowned. ‘Joanne wouldn’t have been involved with a hunter, would she?’

Jacqueline shrugged in reply. ‘Joanne was an old-school Zimbabwean. She told me once she took her daughter on an impala hunt when the girl turned fifteen. The girl never shot again and Joanne said she no longer had the stomach for it, either, but money is money these days, and the Kuwaiti paid her in US dollars.’

Laurel addressed Sandy. ‘Not only is he fabulously wealthy in his own right, but Joanne told us how he has all this ivory and rhino horn stocked away that people are always scheming to get their hands on.’

‘I’m in a wheelchair, Laurel, I am not mentally deficient. I also remember Joanne telling us about the prince’s other treasures.’

‘Yes, well, I think this Sisal’s a suspicious character, myself,’ Laurel said.

‘Faisal, Laurel.’ Thandi had gone back to her knitting, in order to process the new information swirling around. She thought out loud: ‘A suspicious member of a royal family with cash, diplomatic immunity, and a love of cycads.’

Charles raised his eyebrows. ‘Are you thinking what I’m thinking, Thandi?’

‘Road trip?’ SS interrupted. ‘Joanne told us that the prince had issued a standing invitation for us to visit his royal hunting estate if we were ever in Hoedspruit – and we very soon will be.’

Thandi looked to Jacqueline. ‘Madam Chair, we have the Kombi organised for this year’s cycad conference at Nelspruit, and a visit to the Kruger Park next week. Hoedspruit is very near.’

Jacqueline pursed her lips and slid her glasses up her nose. ‘Do we have a motion and a seconder?’

All of their hands went up.

Chapter 2

London, England

By force of habit Joanne Flack looked around her.

In the bush in Mana Pools National Park in the country of her birth, Zimbabwe, she kept an eye out for elephants which, unless they were snapping off branches, were so quiet that one could walk into them before they made their presence felt. In Johannesburg, her home for the last third of her life, she watched the roadside hawkers for signs of anything other than acute sales acumen. Joanne was always amazed how the man selling the sunglasses at William Nicol could see the tiniest movement of her head or eyes that might indicate she was interested in a new pair of knock-off D&Gs.

Not that she had any money.

Now, in London, she watched the people. It wasn’t that she was scared, just out of her natural environment. In Africa there was danger, for sure, and it could be random and horrible, but one could take measures, Joanne reasoned. Avoid the bad areas, keep the nine-millimetre Glock clean, try not to drive at night, keep the windows wound up, but not all the way as it was harder for a thief to smash a partially open window than a fully closed one. In Hwange National Park she didn’t walk around the camp at night because she knew the hyena would be out and the snakes more active, and if she ever came across a lion on foot she knew to stand still.

There were Africans on the streets of London, which at first gave her some measure of comfort, but when she heard their voices they were speaking French, or Nigerian, or some other tongue she couldn’t understand. Her people were the Ndebele, first and foremost. These people in their overcoats and beanies might be from the same continent as her, but that was as much as they had in common. She didn’t understand them, didn’t understand England.

There were six policemen in her field of view as she exited Kings Cross station, dispersed in three pairs, armed and wearing yellow high-visibility jackets. Cops with guns were part of her life in South Africa, but these ones in England were different from the smiling, ambling officers she was familiar with, the ones whose waistlines reflected their skill at fleecing speeding tourists with ‘on-the-spot’ traffic fines. She went down the escalators into the tube station.

The first time Joanne had been to London, with Peter, back in the early nineties when things had still been good for them and their country, none of the bobbies had been armed. The world had changed since then. The policemen above ground, with the sides of their heads shaved, looked like soldiers, and she wondered if some of them had been. They reminded her of her childhood, when the threat of attack had been very real and everyone seemed to carry a gun, even her own mother.

Joanne’s fondest memories of her mother were of the two of them in the garden, tending to her mother’s plants. She remembered going to her first Cycad Society annual general meeting in Mount Pleasant in 1979. Members will please check firearms at the door, the program had said. Her mother carried an Israeli-made Uzi submachine gun – ‘handbag-size, darling, the ultimate fashion accessory’. Joanne smiled to herself.

How odd to have good memories of a war, she thought. A week after that meeting Joanne had shot and killed two men. While there was a terrorist threat in the United Kingdom most of these people passing her by, she realised, would never see a body oozing blood from a bullet wound or know the almost paralysing terror of an armed man coming through the night towards one’s home with an AK-47. These people did not know what it was to feel the kick of the rifle in the shoulder, to smell the cordite and to know that in that instant a life had been taken and another saved. They did not have the nightmares nor feel the pats on the back in the morning from well-intentioned adults for a job well done, for taking two lives; they did not know that wine and beer could dull the pain as one got older, and bring on the tears in the same night. These people knew nothing of death and little of life. People in Africa knew these things and it shaped them, this shared experience of war and trauma, even as it chipped away at them, little by little.

She took a deep breath and hopped on the Northern Line to Embankment, then changed to the District Line and took a westbound train towards Richmond. The morning commuters had given way to tourists, mums with babies, and a noisy group of schoolchildren on an excursion. As usual everyone, apart from the kids, kept to themselves. That suited Joanne.

Kew Gardens was one stop from the end of the line, about where she felt in her life right now, she mused. She knew the route from her previous trips to the UK and wondered if this would be her last mini pilgrimage to the Botanic Gardens. The train was above ground here, and the drab outer suburbs had given way to leafier streets and old red-brick houses. Joanne exited the station and walked the five hundred metres to the Victoria Gate.

She was a member of the Gardens, a gift from Peta that no doubt could not be renewed this year, and showed her card at the entry booth. She couldn’t afford to stay long – her flight left that night – but even though it had only been days since her previous visit she knew she couldn’t leave England without seeing Woody again, possibly for the last time. She needed to leave this country. Extending her return ticket was not just a matter of neither she nor Peta having the money to pay the change-of-booking fee; if the events she had put in place played out as she thought they would, then it might not be safe for her daughter and her family if Joanne continued to stay with them.

When whomever stole the cycad from the society’s lock-up realised what they had then there would be hell to pay. She needed to get back to Africa where she knew where and how to hide, but if she failed and her actions resulted in a loss of life, then she was determined it would not be her child or grandchild. And if that lost life was her own, she would leave this world having seen Woody once more and in the knowledge she had done her best to ensure he would not be the last of his kind.

Once through the gate she turned left. The bitumen pathway shone with dew in between the camouflage pattern of autumn leaves, but the grey sky did nothing to lift her spirits. She zipped up her imitation leather jacket and quickened her pace to ward off the cold.

The Temperate House loomed ahead, the largest surviving Victorian-era greenhouse. It sheltered plants from Africa and Asia which otherwise wouldn’t have survived in the cold, dank English air. Inside, the heady, earthy smell of life calmed her a little.

Joanne went left, heading straight to the Africa section. There were cycads as soon as she entered this wing, but she bypassed them and walked purposefully to the far end, where Woody waited for her.

Joanne looked around, making sure none of the garden staff were watching, then reached out and ever so gently touched him. ‘Goodbye, Woody, my old friend.’

At more than two metres in height Woody, as Joanne called him, was tall for a cycad, which was important, because anything that made him stand out from the other plants – certainly the rest of the cycads – was good, as it might make people stop and read the interpretive panel, where they would learn about the great tragedy of his story. His real name was Encephalartos woodii and the species part of his name was actually pronounced ‘woody-eye’. He was named after John Medley Wood, an English botanist who found the plant in the Ngoye Forest in Zululand in 1895.

A little girl, perhaps nine or ten and wearing the uniform of the group Joanne had seen on the train, came wandering through the Temperate House on her own. Joanne looked past her and saw that the other children were climbing the stairs to the upper viewing level.

The girl stopped in front of Woody. ‘Is this plant very rare?’

‘Yes, he is.’

The girl looked up at her and brushed a strand of golden blonde hair out of her eyes. ‘You call it a he. It’s a plant, not a person.’

Joanne nodded and smiled. ‘You’re very clever, and you’re right, but this plant is, in fact, a male.’

‘Like a boy.’

‘Yes.’

‘Are there girl plants, then?’

Joanne had to be careful with her answer, in case anyone overheard them. ‘Female, yes, or at least there were, once upon a time, but not for more than a hundred years. When this plant was found he was the last of his kind, and no more have ever been seen in the wild.’

‘So is he the only one in the world, then?’

‘Not quite,’ Joanne said. ‘There are a hundred and ten other cycads like this one, all related to him, and all male. They were grown from suckers, little versions of himself that he produced.’

‘Like clones?’

Joanne smiled, her mood momentarily lightened. ‘Yes, exactly.’

‘If there are no girl plants, does that mean this plant won’t ever make babies? I know you need a mummy and a daddy. I’ve got a little brother on the way, and my mummy said she and daddy made him, like they made me.’

Joanne drew a breath, fighting the urge to gather everyone in the Temperate House to her and blurt out the truth. ‘I’m afraid that’s right. This plant will never make a real baby. They’re called pups, in fact.’

‘Pups, like puppies?’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s cute, but it’s also very sad.’

‘It is.’ Joanne swallowed. ‘Very.’

‘Liza?’ a teacher called from the end of the hall. ‘Come here, please. Stay with the group.’

Liza looked up at Joanne. ‘Bye, then. Don’t be sad. Maybe one day your funny spiky plant will get a wife and make proper babies.’

Joanne took a tissue out of her bag and dabbed her eye. She used her phone to take a picture of Woody, made sure no one was looking, then touched one of his leaves again. She checked her watch, turned, and walked through the Temperate House and back out into the cold.

Yes, she thought to herself, one day Woody would make babies, if both she and the plant lived long enough to make that happen. If Encephalartos woodii was to survive and thrive into the future, then he needed to reproduce naturally. Clones took ages to grow and they lacked the genetic diversity a species needed to ensure longevity and survival. The enormity of what she had done weighed heavily on her as she retraced her steps.

From the Kew Gardens station she took the District Line to Victoria then a 170 bus through Chelsea. She had in her mind to visit the Physic Garden, a historic collection of medicinal plants, but first she needed something to eat.

She used the map app on her iPhone to find the way past the rows of beautiful Georgian townhouses. On her phone was a string of missed calls and unanswered SMS and WhatsApp messages from her friends in the society back in South Africa. She missed them, now, but she hardened her heart and tried to concentrate on her surroundings.

London fascinated her, especially the way areas of depressed poverty existed side by side with those of unimaginable wealth. The buildings were the same, but the interiors were where the money was. That and the cars on the road. On this street the Range Rovers and convertible Minis, even a Ferrari, were mirrors held up to the souls of the people who lived here.

Joanne looked up from her phone. Her son-in-law, Phillip, had warned her that on the streets where he and Peta lived in Tufnell Park she should not walk about with her phone in her hand, otherwise a mugger on a moped might grab it. Joanne figured she was safer here, in Chelsea, but kept a watchful eye out nonetheless.

As she walked, Joanne felt her eyes fill with tears. ‘Stop it.’

Her admonitions to herself didn’t work and she wiped her eyes as she stabbed the button at the traffic lights to summon a ‘walk’ sign. She had turned her back on the people closest to her in South Africa and she could not speak to the other person who had been calling her and messaging her: Faisal. Joanne was burning bridges and losing friends, but she firmly believed that her means justified the end she was hoping for. Though it was the hardest decision she’d ever made, she was confident she’d done the right thing by deceiving those who trusted her in order to reverse something the botanical world thought was inevitable.

‘Are you all right, ma’am?’

Joanne half turned and looked up into the handsome face of a policeman. She blinked.

‘Can I help?’ he said. He looked Indian, but sounded Cockney.

‘You haven’t got a cigarette, have you?’

He smiled, not unsympathetically. ‘Afraid not, ma’am.’

‘Are you lost, ma’am?’ asked his rosy-cheeked female partner.

‘No.’ The word ma’am made her sound old, which, as she was pushing sixty, was not entirely unwarranted. She cursed herself again, this time for wanting to smoke; she’d given up years earlier, but moments of stress brought back the old craving.

‘You sure you’re all right, love?’ the male officer asked.

At least that made her feel younger than ma’am, she thought. Love. Hadn’t had that for a long time, either.

Joanne sighed. ‘My son-in-law was made redundant from his job, leaving my daughter and my grandchild with no viable means of support. My husband was shot dead, our farm in Zimbabwe was taken from us, and the pittance I used to receive from my child to keep me afloat has now dried up. I have no professional qualifications other than a keen amateur’s interest in plants and garden design, no savings, no pension and no prospects.’

The two officers looked at each other, and Joanne couldn’t miss their raised eyebrows.

‘I’m fine,’ she sighed. ‘Mustn’t grumble.’

They smiled and nodded and walked on, ahead of her. If any-thing the weather had turned colder and she felt her mood slump again. Joanne followed the officers to the King’s Road and started to think about where she’d have lunch. The footpath was flanked by upmarket eateries and shops selling clothes, watches, accessories and all manner of other goods as well as food Joanne couldn’t afford.

The two officers were still visible in front of her. The helmet of the man, who was much taller than his partner, bobbed commandingly, reassuringly, above the crowd.

Off to her right, in the direction of the Sloane Square tube station, she couldn’t help but notice a man with a long black beard wearing a camouflage jacket. He was coming towards them, barrelling through the crowd with enough aggression to cause a woman to abuse him. The police officers didn’t see him – the male constable was leaning over as he seemed to try and hear something his partner was saying.

As it happened, the man with the beard seemed to be heading straight for Joanne. She wondered if he had some sort of mental illness. She had been quite surprised and confronted to see the number of people living rough and begging on the streets of London since she had arrived.

The man with the beard was reaching into his jacket. Joanne realised that if he stayed on his path, at that pace, he would intercept her, if not run straight into her. The other people on the street were avoiding looking at him, watching the footpath ahead or talking to each other.

Joanne saw a glint of shiny stainless steel. The man with the beard drew a knife that was scarily long and he held it low, and with purpose. The police officers had their backs to her and were half a block ahead. The man came to her. Time slowed; a jolt of shock and fear could have frozen her on the spot, but instead it reignited a long since dormant survival instinct. If she couldn’t flee – and she could not – she needed to fight.

‘Come with me,’ he said in a low voice. He showed her the knife. ‘Say nothing, or I will kill you.’

‘Hey!’ Joanne yelled. ‘Police!’

The male officer started to look around and Joanne realised with horror that she had done the wrong thing.

‘He’s got a knife!’

Her warning call came too late. The bearded man turned his attention from her and charged at the tall policeman from behind.

‘Allah-u-Akbar!’ The man raised his hand as he yelled the words and struck downwards with the knife, aiming for the junction between the officer’s neck and shoulder, above the stab-proof vest he wore. Blood erupted and spurted over the constable next to him. She reached for her pistol but the attacker was quicker, slashing at her neck.

People screamed and ran. Joanne raced towards the bobbies and when she reached them the male officer toppled backwards onto her, pinning her to the ground. The man with the knife stepped agilely to the side.

Joanne looked up into the bearded man’s eyes but he barely spared her a glance now. A man in a suit was trying to grab his arm and the attacker swung and punched him in the face. Joanne could see now that he had a knife in each hand, and he used his left to plunge a blade into the other man’s belly.

Blood was flowing from the male officer’s neck wound over her face and her hands as Joanne tried to wipe her eyes and fought to slide out from under the man writhing on top of her. She put an arm around him and her fingers brushed the pistol in his holster. Joanne grabbed it with a slippery grip, pulled the pistol free and stared at it.

Glock 17, no safety catch – double action trigger.

Joanne rolled the police officer off her and hauled herself up onto one knee. Having dispatched the man in the suit, the bearded man was coming for her again.

Joanne raised the pistol in a two-handed grip and fired, twice in rapid succession.

She heard the bangs and the clinking of the spent rounds hitting the pavement. The world moved in slow motion. Her moments of terror at being accosted and grabbed had been stilled, subsumed, by the speed at which everything had happened, by the familiar, reassuring grip of the pistol, by the buck and the noise and the smell of the bullets leaving the barrel.

She stood, and now the bearded man lay at her feet, gasping his last gurgling breaths of life as he looked up into her eyes. People were screaming, running, but to her they moved and spoke in muffled slow motion. She had killed, again, her brain registered.

The pistol hung loose by her side now, impossibly heavy, dragging her hand down. She wanted to crumple to the ground, spent after the rush of adrenaline. Had this just happened?

The yells of the passers-by, the wail of a siren increased in volume and pitch, bringing her back into the moment as she looked around. People were coming to her. It had not been a dream; it had been real.

She looked down at the man again. He was dead. ‘Come with me,’ he had said to her.

‘Where?’ she asked the corpse out loud.

New Jersey, United States

‘Forty-five my ass.’ Rod Cavanagh slammed the remote control down so hard on the kitchen bench that his twenty-year-old son, Jake, looked up from his phone.

Rain beat against the window of his modest house. The tree outside was bare, the leaves scattered by the blustery fall winds. The bleakness of the day matched his mood this morning.

The television news anchor droned on, over pictures of a crime scene roped off with blue-and-white police tape and filled with forensic investigators in one-piece white suits. ‘Joanne Flack, Zimbabwean born, but now resident in South Africa, was visiting her daughter in London and sightseeing in the capital when she saw the alleged lone-wolf terrorist, Jamal Hussein, draw two knives and attack a pair of police officers in front of her. Flack took one of the injured officers’ pistol and fired two shots, killing Hussein. Scotland Yard said today that Hussein, born in Mali, West Africa, had travelled to England on a South African passport. The National Rifle Association has praised …’

‘Oh, for Pete’s sake …’

‘Chill, Dad,’ Jake said.

‘Don’t tell me what to do. I’m the father here, I call the shots, and that woman is not forty-five years old. Whatever happened to good old-fashioned fact-checking?’

‘Whoa, dude. What exactly are you talking about?’

Rod picked up a piece of toast and pointed at the television screen which showed, for perhaps the hundredth time that morning, the jerky phone camera vision of a blonde woman shooting down a terrorist. For the sake of the squeamish the video ended before the impact of the bullets could be seen. ‘Her.’

Jake looked up. ‘The woman who killed the terrorist? She looks younger, if anything. She’s badass.’

‘She’s at least the wrong side of fifty-five now,’ Rod said.

‘Wait. You know her, Dad?’ Jake actually put his phone down.

‘I’m glad to see I’ve at least got you off Facebook for two minutes.’

‘Um, hello. Tinder, Dad.’

‘TMI,’ Rod said. ‘Yes, I know her.’

‘How? Can you get me her phone number? She’s kinda hot, in a cougar way.’

‘She’s old enough to be your mom,’ Rod said.

They were both quiet for the next few seconds. Rod felt the stab wound in the heart again, as, no doubt, did Jake.

‘Sorry, buddy,’ Rod said.

Jake smiled. ‘It’s OK, Dad. So, how do you know her?’

Rod shook his head. ‘She’s Zimbabwean, lives in South Africa. I investigated her, twenty-two years ago in –’

‘The great plant sting. You may have mentioned that like, oh, maybe a thousand times.’

Rod frowned. Jake was a good kid and they were as much buddies as father and son – at least he liked to think so – and while Jake was only joshing, Rod knew he was guilty of telling the story of his biggest undercover operation too many times. After all, it wasn’t every day that you busted an international ring of endangered cycad smugglers. At the time it had been news, even made the New York Times magazine, but in this age of the war on terror no journalist or chief financial officer cared too much about Fish and Wildlife Service investigations or the international trade in endangered plants.

Rod had been lauded by the department in public as a hero, but after the prosecutions were over his career as an investigator had been quietly but irrevocably terminated. It turned out that the end did not always justify the means and Rod had been guilty of some serious errors of judgement during the operation.

‘Yeah.’ Rod stared at the television, watching the re-runs of the portrait shot of Joanne Flack and the slow-motion vision of her taking down an honest-to-goodness bad guy. ‘She’s barely changed.’

‘What was that, Dad?’ Jake asked.

Rod looked up from the flat-screen on the kitchen wall. ‘Oh, nothing, son.’

‘Dad, are you OK?’

Rod sipped his coffee. ‘Sure, why?’

‘You looked a little lost, just then. Like you were flashing back or something. Was it about Mom?’

It had been two years since they’d lost Betty to breast cancer and it still hurt. Rod felt his cheeks flush. ‘Yes, I guess, buddy. Go on, get off to work, now. Wall Street might crash without its latest young hotshot intern.’

Jake chuckled. ‘OK. And Dad?’

He looked at his son and wiped his mouth with a paper napkin. ‘Yes?’

‘I’m proud of you, really. And the plant world sleeps safe knowing tough guys like you once put their lives on the line for them.’

Rod screwed up the napkin and threw it at his son. ‘Get out of here. Go sell off some junk bonds to little old ladies and I hope you choke on your Dom Pérignon.’

Jake got up and put his satchel around his neck. ‘Love you, Dad.’

‘Ditto.’

Rod drained the last of his coffee. When Jake had left he switched channels to watch the story on Joanne Flack all over again.

Just so he could look at her.

Chapter 3

Mali, West Africa

The woman in the burqa, clutching a tattered hessian sack to her chest with her left arm, passed all but unnoticed down a dusty street flanked by an open drain whose smell ripened in the afternoon heat.

A bored jihadi in a black turban picked his nose as he leaned on the receiver of his Russian-made 12.7-millimetre DShK heavy machine gun on the back of a battered Toyota HiLux technical. The gun’s nickname was Dushka, beloved one, but the woman knew from personal experience there was nothing to like about that thing unless you were firing it.

A dog paused, looking up from his foraging in the gutter to see if the woman had a scrap for him, but she carried on. She quickened her pace when she heard the call to Asr, the afternoon prayer, blare out, scratchy and tinny from a speaker atop the mud-walled mosque at the end of the street. The fighters behind her would be climbing down from the armoured vehicle, unrolling their prayer mats.

She turned right down a narrow alleyway and, away from the vehicles and machine guns, back into the Middle Ages, save for the single-use plastic bags that littered the way. There were no signs for Pepsi or Coca-Cola, no radios blaring, no satellite TV dishes, no vestiges of the twenty-first century. That wasn’t all bad, she thought to herself, but the pile of rocks she passed was sticky with blood and hair and the ground around it was stained, all that remained of a woman who had been caught having sex with a married jihadi. The man had been flogged, apparently, but after the stoning the woman had been dragged into the desert, tied by the ankles with a rope fixed to the back of a technical. If she was still alive after being pounded by rocks the last ride of shame would have finished her off.

‘Waqf.’

She stopped, not daring to look behind her at the man who had just told her to stop. She heard the scuff of his sandals in the dusty street and controlled her breathing.

‘Salaam aleikum,’ he muttered as he came up to her.

Through the gauze covering her eyes she answered, ‘Aleikum salaam.’

He reached for the sack she held and she clutched it tighter. She leaned forward and a couple of dates spilled out of the top. The man laughed and his foul breath penetrated her veil. She looked at the rifle on his back as he bent to pick up the dates. The AK-47 was rusted and dirty, slung so as not to be readily accessible. It would take him seconds to bring it to bear if he needed to use it.

Amateur, she thought.

He stood straight, popping one date in his mouth with dirty fingers and pocketing the other. She stood there and revised her opinion of the man, slightly, when she saw how he looked down at her one foot that was visible beneath the hem of her robe. Her sandal was locally made, simple, grubby, yet her foot, darkened with several coatings of spray tan, was ornately decorated with henna. Maybe he was just a lecherous young man, she thought, or maybe he was making sure there was a woman under the burqa. Either way, the little touch of painting her feet had worked.

He waved her on. She gave a deferential little nod and carried on down the alleyway.

Two more men, both also armed with AKs, walked by her, not sparing the woman in black a second glance. This was why she was here. In this town she could move almost unseen, right up to the ornately carved door set into the deep recess in the mud-brick wall. The guard, who had been given dispensation from praying but nonetheless was reading from a well-thumbed pocket edition of the Qur’an, looked up from the holy book when he realised she had stopped in front of him.

This time she proffered the bag to him, showing him the pile of remaining dates.

‘Shukran.’ He took one and smiled.

Pity, she thought. He had nice eyes. She wondered if he had been one of the men who had raped the girl. She dropped the sack and as the young fighter bent to retrieve it she pulled her right hand from under the folds of her robe and drove the point of the vintage Fairbairn–Sykes commando fighting knife up under the man’s ribcage and into his heart. She clamped her free hand over his mouth and pushed him deep into the shadowed vestibule, against the heavy door, and held him, still, until he died a few seconds later. Her black robe absorbed and hid the blood that flowed down over her hand.

She spoke softly, the throat microphone transmitting her voice to the US Navy Seahawk helicopter orbiting out of sight and sound over the desert ten kilometres away. ‘One tango down, breaching now.’

‘Roger,’ came the disembodied voice in her ear. It was Jed Banks, one of the CIA’s top men in Africa. Jed was an ex–Green Beret, a combat veteran who had served in Afghanistan, and she felt better knowing he had her back.

She knew the door was locked and bolted from the inside so there was no point in looking for keys on the dead guard. She reached under her robe for the breaching charge she had already prepared in advance. From around her neck she slid forty-five centimetres of detonating cord, with a further length of shock tube attached to a blasting cap on one end and a primer on the other. She peeled the cover off the double-sided tape attached to the det cord and stuck the explosives-packed snake to the door. She backed along the wall and initiated the primer by slapping a metal initiator punch into the primer tube.

The door was shattered, splinters and dust shooting out into the alley. She took a stun grenade from a pouch under her robe and pulled the pin. Before the smoke had begun to clear she was through the door. She had modified her burqa with velcro fasteners and it came apart as she raised the Heckler & Koch MP5 machine pistol, slung around her neck in front of her, with her right hand. On top of the MP5 was a camera, which she switched on. She followed the map of the building in her mind and down the stone-flagged corridor was a door on her right. She tossed the stun grenade inside and as it went off she entered the room, searching for targets.

The eyepiece of her veil, which was still in place, shielded her vision from the bright flash of the grenade, and she saw a jihadi crawling across the floor from his prayer mat towards his rifle. She fired a double tap, two shots in quick succession, into his back, and he fell flat and motionless.

She carried on through to a door on the other side, which she kicked open. She fired into the room, catching one of the two men inside in the shoulder and spinning him around. The second man had his rifle up and was searching for her when she fired again.

Tap-tap. The man fell. She dispatched him with a third shot, between the eyes.

‘In,’ she said into the mouthpiece, voice calm, heart pounding. ‘Three more tangos down. Bring it.’

‘Roger,’ Jed said. ‘On our way.’

There was a door on her right that was not on the plan she had committed to memory. She tested the handle and found it was unlocked. She kicked it open and raised her weapon. It was a storeroom, uninhabited but stacked high with stuff she instantly recognised as being valuable. There were elephant tusks, maybe thirty of them, the ends of the ivory still bloodstained; a dozen rhinoceros horns stacked in a corner; an open sack of marijuana, and a stack of what looked like a dozen small fuzzy tree trunks, each no bigger than a round side table. One trunk was bigger than the others, about a metre tall, and its plastic covering had been partially undone, revealing its rough, diagonal-patterned surface. The camera on top of her H&K would record it all. She carried on.

She had another explosive breaching charge in a pouch on her combat vest. She placed the charge against the locked door that faced her and blew it open.

She knew this would be the hardest target, the final guard who would be standing over the package, a twenty-four-year-old American aid worker, the daughter of a US senator, who had been held hostage for the past six weeks. The man would be ready to kill his captive and die for his cause rather than let her be rescued. She knew she might be too late.

She paused deliberately. The guard would be expecting a force of SEALs to come rushing through the door. She let the H&K dangle from her neck again and closed the folds of her burqa, reattaching the velcro. She drew the Glock 19 from her belt and held it behind her back.

‘Allah-u-Akbar!’ she screamed, then went through the door.

Through the smoke from the charge she saw the guard as well as the woman lying on the filthy bed, her mouth covered with duct tape. The man had his AK-47 up but when he saw the black-clad woman enter he hesitated, as she hoped he would, and lowered his rifle a fraction.

It was enough. She brought her pistol up and fired twice, hitting the man in the chest. She put a third round into his head for good measure, and because of the state of the woman she had come to rescue.

The woman was handcuffed, her exposed skin scored with cuts and pocked with what looked like festering burns, each the size of the end of a lit cigarette. She brought the Glock up again and fired through the chain joining the cuffs. She reached down and ripped the tape from the aid worker’s mouth.

The young woman blinked and cowered on the bed. ‘Who … who are you?’

‘My name is Sonja Kurtz. Don’t let the accent fool you – I’m CIA. I’m here to rescue you and kill as many of these fuckers as I can.’

The hostage began to cry, but there was no time for a hug. Sonja grabbed the woman’s wrist and pulled her gently but firmly off the bed to the door.

‘Come with me.’

Sonja led the aid worker through the rooms, stepping over dead bodies. She had the H&K at the ready again and passed the Glock to the young woman. ‘No safety catch. Just point and pull the trigger.’

The young woman nodded dumbly. At the entrance Sonja peeked out into the street and a hail of heavy-calibre bullets raked the walls either side of her. She had glimpsed the vehicle at the end of the alleyway.

‘Technical, blocking the exit,’ Sonja said, so the throat mic would pick it up.

‘Got it,’ Banks replied. ‘UAV’s on it. Clear to launch?’

‘Unleash hell,’ Sonja said.

Orbiting above them, out of sight, was a Global Hawk Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, what the media liked to call a ‘drone’, but in reality a sophisticated jet-powered platform of destruction. At Jed’s order a Hellfire missile was launched.

Sonja watched the streak of smoke come out of the sky and the next second the HiLux erupted in a ball of flame and smoke and the machine gun stopped firing.