5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ingwe Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

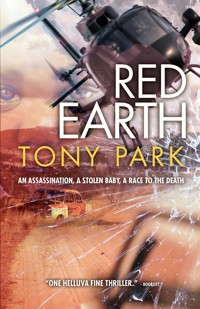

An assassin is on the loose and a baby has gone missing in South Africa - it's up to a vulture researcher and a helicopter pilot track down the innocent and stop the guilty. How will they know the difference?

On the outskirts of Durban, Suzanne Fessey fights back during a vicious carjacking. She kills one thief but the other, wounded, escapes with her baby strapped into the back seat.

Called in to pursue the missing vehicle are helicopter tracker pilot Nia Carras from the air, and Mike Dunn, a nearby wildlife researcher, from the ground.

But South Africa’s police have even bigger problems: a suicide bomber has killed the visiting American Ambassador, and chaos has descended on Kwa-Zulu Natal.

As the missing baby is tracked through wild game reserves from Zululand to Zimbabwe, Mike and Nia come to realise that the war on terror has well and truly invaded their part of the world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

About Red Earth

An assassin is on the loose and a baby has gone missing in South Africa - it's up to a vulture researcher and a helicopter pilot track down the innocent and stop the guilty. How will they know the difference?

On the outskirts of Durban, Suzanne Fessey fights back during a vicious carjacking. She kills one thief but the other, wounded, escapes with her baby strapped into the back seat.

Called in to pursue the missing vehicle are helicopter tracker pilot Nia Carras from the air, and Mike Dunn, a nearby wildlife researcher, from the ground.

But South Africa’s police have even bigger problems: a suicide bomber has killed the visiting American Ambassador, and chaos has descended on Kwa-Zulu Natal.

As the missing baby is tracked through wild game reserves from Zululand to Zimbabwe, Mike and Nia come to realise that the war on terror has well and truly invaded their part of the world.

For Nicola

Contents

PART 1

Prologue

They called him Inqe and he flew all over southern Africa, searching, always searching.

The sky was clear, the day warm, perfect weather for flying though summer’s storms would soon be on their way. The golden grasslands and crops passed below him. Inqe was heading for the rolling hills and coastal wetlands of KwaZulu-Natal, nearly seven hundred kilometres south of his base in the Kruger National Park. He wasn’t alone; his wingmen were either side of him.

They crossed the monumentally scaly back of the dragon, the Drakensberg Mountains, and the greener, lusher land opened out beneath them. Specks in the distant sky caught Inqe’s eye and he changed direction to head towards them. As he flew closer he could see the fliers were in a landing pattern, each holding in perfect formation until it was his or her turn to land. Inqe joined the circuit, as did his wingmen.

As he orbited, waiting for his chance to touch down, Inqe saw there was yet more traffic in the air. Over King Shaka International Airport, a Boeing was on its final approach, and a small helicopter was coming towards them, low, fast, hellbent on a mission of some sort.

He returned his attention to the others immediately around him, and their target on the ground below. Those that had landed were already hard at work. He hoped he wouldn’t be too late. On the thermals rising from the sun-warmed African grasslands he smelled the sweet scent that had brought the other fliers, and which had lured Inqe and his wingmen to Zululand.

Death.

Chapter 1

‘ZAP-Wing, this is Tracker,’ Nia Carras said into the boom microphone attached to her headphones. ‘I’ve located your target.’

She adjusted her course slightly and pushed her Robinson R44 helicopter into a wide turn to stay clear of what looked like a swirling tornado of black dots against the blue sky. ‘It’s a kill all right, over.’

‘Roger that, Tracker,’ said Simon, the operations officer on duty at ZAP-Wing, the Zululand Anti-Poaching Wing, a force of air assets patrolling twenty-four game reserves in KwaZulu-Natal Province. ‘Can you confirm it’s a rhino, over?’

Nia keyed the microphone switch on the stick. ‘Moving in closer, ZAP-Wing, but I’m taking it easy. There are vultures everywhere here.’

Nia tightened her orbit and, checking to either side and above her, brought the R44 lower. The carcass of the dead animal below was rippling with the bobbing heads and beating wings of scores of vultures, all fighting for the tastiest morsels of their lifeless prey. The noise of the approaching helicopter startled some of the birds, which began the ungainly process of taking off. Each vulture’s wingspan was up to two metres wide.

‘Getting visual now,’ Nia said into her radio. She was used to continually scanning the sky around her, and her instruments; her eyes rested momentarily on the satellite navigation system in the cockpit. ‘Hey, ZAP-Wing, you do know this kill is outside the park, right? Over.’

Nia peered through the rising curtain of birds, trying to catch sight of something that would identify the animal they were feasting on. The most prevalent and serious big game targets of poachers in the province were rhinos.

‘Negative, Tracker,’ said Simon. ‘We received a report on the hotline from someone who thought the kill was inside the park, over.’

‘Well, they got that wrong. It’s just outside, in the communal lands.’ A white-backed vulture, startled by the noise of Nia’s engine, alighted from the head of the dead beast. ‘Wait, ZAP-Wing. I see a horn and it’s not of the rhino variety. It’s a dead nguni, over.’

‘A cow?’

‘Affirmative. Something odd there, too. I’m going down for a closer look.’

‘Your call, Tracker, we appreciate you going out of your way in any case.’

Nia could hear the diminishing interest in Simon’s voice. If it wasn’t a dead rhino in the Hluhluwe–iMfolozi Park then there would be no need to call in the police or national parks anti-poaching teams. The Hluhluwe Game Reserve and the adjoining iMfolozi Game Reserve, now designated as one park, were home to large numbers of black and white rhino. The cow had probably been hit by a car or a truck; it was close to the main tar road that ran between the two reserves, towards Mtubatuba.

She should really have been heading back to her base at Virginia Airport on the coast just north of Durban, but she had some fuel left and it was a beautiful day for flying. It had been a good morning, even if it hadn’t started out too well. She’d received a call-out early, just before six, from the control room of Motor Track, the vehicle tracking company that Coastal Choppers, her employer, was contracted to. A Volkswagen Jetta had been stolen from outside a pub in Ballito and was last seen heading for the N2. Her tracker, John Buttenshaw, who normally flew with her, had received the call at the same time. At that time of day Nia had made it to Virginia from her home in Umhlanga Rocks in nine minutes, but when she’d arrived at the gate to Coastal Choppers it was still locked and the lights were off in the office. Nia’s cell phone had rung just then.

‘John?’ she’d asked as she saw his number flash on the screen. ‘What’s wrong?’ John, who was a trainee helicopter pilot trying to get his hours up in his spare time, lived much closer to the airport, just a kilometre away, and by the time Nia arrived he’d normally be there getting everything ready. Together, they would push the Robinson R44 outside and she would start it up.

‘Sheesh, you won’t believe it,’ John said, sounding stressed. ‘I pulled out of my house and this drunk guy came screaming round the corner and T-boned me.’

Nia had checked that John was OK – he was – but the drunk had cracked his head on his windscreen and John was waiting with him for an ambulance. It wasn’t ideal for her to fly a tracking mission by herself, but John would be tied up for an hour or more, so she’d wheeled the R44 out by herself, grabbed John’s tracking pack from the office, and taken off alone to find the stolen Jetta.

It had been a pretty uneventful mission. She’d picked up the signal from the radio tracking device hidden in the car north of the town of Hluhluwe and found the vehicle abandoned on the side of the N2. The Motor Track ground crew, her boyfriend, Angus Greiner, and his partner Sipho Baloyi, had arrived about twenty minutes after her while Nia orbited the vehicle. She’d done a low-level fly past and Banger – Angus’s nickname – had blown her a kiss. Over the radio they’d confirmed the car was fine – luckily for the owner he or she had neglected to fill the fuel tank lately and the Jetta had run out of fuel.

‘Probably some okesjust looking for a quick ride home from the pub,’ Banger had theorised over the radio. ‘We’ll put some fuel in it and I’ll take it to the owner. Sipho will follow me. Catch you later, babe.’

Some of the vehicles they tracked were stolen for parts; others were destined to be resprayed and smuggled across the nearby border into Mozambique; some were taken to be used in a robbery; and others, like the Jetta, were taken because they provided a quick, easy ride home. This had been a good morning, Nia told herself. The vehicle had been recovered, no one had been held up or shot and no other crime committed, and Banger and Sipho had not had to face down a gunman or two. She worried about him constantly. Like the other ground crews, Banger and Sipho were always spoiling for action and were sometimes brave to the point of being stupid. But Nia acknowledged that Banger’s recklessness was part of the attraction she felt for him.

Nia flew a slow orbit around the dead cow, keeping a careful watch out for flying vultures – a hit from one of those massive birds could bring her down. Through the Perspex windshield Nia could see several birds, maybe a dozen or more, still on the ground around the carcass, most of them with their wings outstretched as though they were sunning themselves. The majority of the vultures, however, had taken flight. She brought the helicopter in as close as she dared.

‘ZAP-Wing, there’s a problem here,’ she said as she settled into a hover.

‘What is it, Tracker?’ Simon said.

The vultures on the ground were not moving at all. All the birds that were able had taken off. The bones of the cow’s rib cage had been stripped clean and were shining bright white against the dun-coloured grass and the red gore of what was left of the animal.

Nia keyed the radio switch. ‘Better call your vulture guy, ZAP-Wing. There’s a span of dead birds on the ground here.’

*

Suzanne Fessey closed the door of the house in Hillcrest she and her husband had been renting for the last six months. She picked up her baby and took him to the Toyota Fortuner.

She felt mixed emotions about leaving the house, about taking the baby when she would never see her husband again. They hadn’t been ready for a child, hadn’t expected or wanted one, but they had decided to go through with the pregnancy.

Suzanne had cleaned the house from end to end, vacuuming, scrubbing and wiping down everything. There was no trace of her left there. She unlocked the Fortuner and put the child in his car seat, squeezed in among her possessions. He wriggled and gurgled as she fitted his restraints – he was active and adventurous and she knew he would be walking soon. She wasn’t taking a lot with her, but it was surprising how much stuff one accumulated.

With her son securely belted in, Suzanne reversed out of the driveway and drove out of the small walled estate’s gates. She turned right and headed down the street to the on ramp to the N3, heading towards Durban. It was a warm day and she turned up the air conditioner and switched on East Coast Radio.

She caught the tail end of the news. The Sharks had beaten the Stormers on the weekend. The recap of the news was about more load shedding and a corrupt local politician. Nothing out of the ordinary there, she thought to herself.

Suzanne turned off the radio before the music began again. She checked the clock on the dashboard. If she didn’t take too many breaks she would be in Mozambique in a bungalow on the Indian Ocean by four that afternoon, after which the rest of her life would begin.

She skirted Durban and took the N2 north. Suzanne had deliberately left late to miss the peak-hour traffic and the motorway was flowing well. Soon she was clear of the city. In just under an hour she would check the news again. She turned and looked back at her son. ‘Not long now.’

Emerald-green sugar cane fields lined the road and off to her right she could see how the sky turned a deeper shade of blue where it met the sea, which was out of sight, but not out of reach. As she crossed a bridge a long-crested eagle took flight from its perch on the railing. Suzanne watched it fly off into the clear sky. She remembered another time, another life, when she was a child and her parents used to take her into Hluhluwe–iMfolozi to see the animals. Her father was interested in birds, but Suzanne wasn’t; she hated anything her father liked. She had left home at seventeen, lived on the streets, and the nightmare that was her life, not eased by the daggaor the tic, or even the heroin, had been almost as bad as her time at home. But she had turned her life around, with the help of a good but weak man. And he had given her a child. Suzanne had realised two things late in life – she was a fighter, and she was a survivor. She would find a better place.

Coughing, spluttering and an awful smell from the back made her turn. ‘Oh, no!’

Her son had vomited, all down his front. The stench made her gag. Suzanne banged the steering wheel in anger. ‘Shit, shit, shit!’

Up ahead, beside a bus stop layby, was a small caravan. Suzanne saw two cars there, one a beaten-up bakkieattached to the caravan, the other a red Volkswagen Golf. As she drew closer she saw that the trailer was a mobile boereworsroll stand. It was as good a place as any to stop and clean the baby with some wet wipes; as tough as she was she couldn’t stand the smell. She slowed down and pulled over.

*

Shadrack Mduli looked in the wing mirror of the Golf and saw the white Fortuner indicating left to pull over at the caravan. He nudged his partner, Joseph Ndlovu, in the ribs.

‘Can you believe this shit? It’s like home delivery,’ Shadrack said.

Joseph stretched and yawned. ‘What, brother? I was sleeping. What are you talking about?’

Shadrack pointed over his shoulder with a thumb. ‘Check. Late model Fortuner, white, single woman driving. Our luck has changed. She’s coming right to us.’

This, Shadrack realised, would be even easier than he thought. The woman was pulling over a good fifty metres away from the caravan selling worsrolls. He checked the mobile eatery and could not even see the cook inside. If he couldn’t see the chef, then the chef couldn’t see them.

The woman got out of her car, clearly looking flustered, and walked around to the rear door. ‘Let’s go,’ Shadrack said. Joseph unfolded his lanky frame from the small Golf.

Shadrack pulled the nine-millimetre pistol from the waistband of his low-slung jeans. With Joseph following he raised the gun and strode up to the woman. ‘Give me your keys, now!’

She turned to him. Shadrack closed the gap between them and pointed the gun at her face, just centimetres away. ‘Now! I said give me your keys or I’ll blow your head off.’

The woman glared back at him. Shadrack was used to his victims screaming or crying or madly scrambling for their keys to give to him, not just staring back at him. He had never killed a person during a robbery, but he fully believed he could do so. This woman mocked him with her stare. Well, she would be his first. He tightened his finger on the trigger, hoping the muscle action would still the slight tremor he felt in his hands. ‘Last chance. Don’t just stand there.’

‘Shad … brother,’ Joseph called behind him.

Shadrack risked a quick sideways glance and saw that Joseph was at the driver’s side door.

‘The keys are in the ignition,’ Joseph said.

Shadrack saw the movement in his peripheral vision but he was too slow to move. He felt the blow on his wrist at the same moment and pulled the trigger, instinctively. His shot went wide. The stupid woman had hit him – no one had ever defied him like that. Her other hand was moving as well. He swung his gun hand back towards her, but before he could fire he was on his back, on the ground, his ears ringing from the blast of another gunshot. How could that be? he wondered. He was sure he hadn’t fired again.

Shadrack tried to raise his hand to aim his pistol, but he felt too weak to do so. He looked down and saw red blossoming across his chest, soaking the fabric of his white T-shirt. He saw the woman’s feet step over him, heard the crunch of her shoes on the gravel of the layby. The Fortuner’s engine roared to life and the wheels spun on the loose surface.

‘My baby!’ The woman turned and punctuated her cry with two shots at the escaping vehicle.

The pain hit Shadrack as the numbness from the shock of the bullet’s impact wore off. He screamed with the effort of rolling over. His eyes were clouding and the effort it took to stretch out his right arm and hand nearly made him black out. It was worth the pain, though. The woman was a blurry target beyond the tip of the barrel. Curse her. He pulled the trigger, once, twice, three times, and had the satisfaction of seeing her stumble before his world ended.

Chapter 2

Themba Nyathi felt ill.

Health-wise, he knew he was perfectly fine. He had checked his pulse rate against the second hand of his cheap Chinese watch, and had inspected the inside of his mouth and throat in the cracked mirror in the school bathroom. He’d even had his friend, Bongi, hold the back of his hand against his forehead to see if he had a temperature.

‘You’re fine.’ Bongi had laughed at him, good-naturedly. ‘Maybe you’ve got something else on your mind.’

Themba had frowned in the hallway as they bustled their way out into the hot, humid Zululand morning. It was always hot in Mtubatuba. It was hot and dry during the winter, and hot and wet in the summer. But the sun and water brought life and it sprang up everywhere, in the rich green grasses, in the sugar cane in the fields, in the trees in the bush and the animals who chose the lush, wet summer to give birth.

Themba was more aware of the world around him than he’d been at any other point in his seventeen years, and he had good reason to appreciate the natural environment. It may very well have saved his life. He’d explained this theory to Lerato, the new girl at school, how his recently discovered love of the bush had helped him come to terms with some terrible things that had happened in his life. He had neglected, however, to tell Lerato that some of those bad experiences were of his own making. This omission, he was now sure, was what was making him feel sick.

‘Hey, you’re always reading that book between classes, Themba,’ she had said to him during the morning break.

Themba had looked up. Lerato Dlamini was the talk of the school. She was beautiful, intelligent, and the word was that her father was very wealthy, a former ANC member of parliament who owned a trucking company and two cane farms.

The smart guys, the bad guys, the football players, every boy in school in fact, were all vying for Lerato’s attention, but she affected a haughty air. Themba liked the word ‘haughty’, having recently discovered it, and tried to use it whenever possible. It made her seem unattainable, and that only increased her attraction.

Themba blinked. ‘Excuse, me?’ His two words were punctuated with a cough as though his response threatened to choke him.

Lerato looked down at him, like a giraffe whose attention has been piqued by some little creature below her. ‘That book. Animals. Why are you so interested in that stuff?’

Themba had licked his lips and then looked at the cover of his book, as if only just now discovering what it was about. ‘It’s … it’s not only animals. It’s … it’s birds and snakes, and, and, even some trees and plants.’

Lerato had laughed out loud, for real. ‘Oh, well thatmakes it all right then. I just lovesnakes and trees.’

Themba did not know why she was teasing him, but all of a sudden it didn’t matter. The important thing was that she knew he existed and, even better, she was talking to him – even if she was ridiculing him. ‘Did you know Inkwazi, the African fish eagle, mates for life?’

Her eyes widened.

Idiot, Themba said to himself. He’d regurgitated the last piece of information he’d read from his field guide and the implications of what he’d said pumped through his body like a black mamba’s venom. He felt his body start to stiffen with paralysis.

‘That’s really nice.’ Lerato set her rucksack full of books on the ground and sat down on the wooden bench next to him. ‘I never thought of birds falling in love and getting married.’

Themba had been bracing himself for another jibe. Perhaps as a defence mechanism his ears were shutting down, because Lerato sounded like she was talking to him underwater. But he picked up something of what she said. ‘Nice?’ he croaked.

‘Yes, nice.’

He had dared to turn his head a little, to look at her beautiful face, and to his surprise he saw she was smiling at him, but not in a mocking way. She had said something about love, hadn’t she?

Themba felt blood forcing its way past the coma-inducing poison in his veins. Feeling returned to his fingertips – he wiggled them surreptitiously to make sure he was still alive – and a switch tripped in his brain. ‘When it comes to animals, birds and other wildlife, we have to be careful of anthropomorphism, which means –’

‘Ascribing human qualities to animals – I’ve heard the word before,’ Lerato said.

‘Sorry.’ He was impressed. Like ‘haughty’, he’d thought of ‘anthropomorphism’ as one of his personal words. He was happy to share it with Lerato, though, more than happy. ‘But, yes, it is “nice” to think of two creatures spending their whole lives together, and if the fish eagles were human we’d probably put that down to love.’

She laughed again. ‘You’re funny.’

He felt the paralysis creeping back. Even if she was just making fun of him, he didn’t want her to leave. ‘Male and female steenboks, little antelope, also sort of live together, sharing the same territory.’

‘Serious? I didn’t know there was this much monogamy in the world.’

Just watching her lips move as she formed the words, and catching sight of her perfect, even white teeth when she smiled, brought the life back to him, made him glad to be alive. Now all he had to do was think of something witty to say, to keep her there, next to him. But he couldn’t.

‘What about lions?’ Lerato had asked, filling the chasm of silence that had opened between them in just three seconds.

Themba exhaled, then closed his mouth, not wanting her to notice his relief. ‘Oh, no, lions don’t mate for life, far from it. Lionesses will mate with several different males during the course of their lives, depending on which males have taken over the pride. Males come and go. As they get older they’re challenged by young males for control of the pride.’

Lerato laughed again. She laughed a lot. ‘Gangsta.’

Themba felt like she might be mocking him again, but to his surprise, Lerato reached out and put a hand on his forearm. It felt like an electric shock. ‘You’ve seen lions for real, right? In the wild, not in a zoo?’

He’d nodded his head. ‘Yes, in the Hluhluwe–iMfolozi Park. It was during my training as a youth rhino guard.’

‘I remember, you went and lived there, in the bush, for a month.’ Lerato couldn’t hide her incredulity. ‘Are you mad?’

It had been Themba’s turn to laugh. ‘Yes, it was a month, how did you know?’

‘I was at the talk you gave to the school a few weeks ago.’

Themba felt an acute flush of hot embarrassment. ‘You listened to my talk.’

She rocked her head from side to side. ‘Well, a little bit of it.’

Themba had been encouraged by Mike Dunn, the coordinator of the month-long course, to find a forum where he could address people about what he’d learned, and Themba had reluctantly asked the school principal for permission. To Themba’s horror, the head of the school had agreed and he’d found himself addressing more than four hundred students one sweltering Monday morning. He had stumbled through his written speech and been angered to see some of the older boys and girls talking while he delivered it. The younger students, however, had seemed interested in his stories, particularly the one about the lion.

‘You were in a tent, I remember you saying,’ said Lerato, ‘and you could hear two lions walking around you in the middle of the night. You said it sounded like they were purring, but, like, really loud. You must have been terrified.’

Sheremembered!Themba felt his heart swell. ‘It wasn’t that bad. The main thing our instructors drilled into us was to keep our tents zipped up and to stay very quiet. It wasn’t easy.’ In truth, Themba had been shaking in his sleeping bag, absolutely petrified once his tent-mate, Julius, peeked out the window of the tent and saw the outlines of the two massive lionesses. Themba had thought he would die for sure. Julius had suggested they make a run for it, to a minibus van parked at the campsite; this had galvanised Themba into action, hissing furiously to his friend not to even think of doing something so stupid.

‘Serious?’ said Lerato.

‘You have to remember that lions hunt by sight and sound, not smell. They’re like house cats chasing a mouse or a gecko. If their prey is running, then they will chase it, and there is no way a human can outrun a lion.’

Lerato sagged a little. ‘I’ve never seen a lion, not even in a zoo.’

‘I’ll show you one.’ The words had tumbled out of Themba’s mouth before he’d even thought about how he might do that. He had no car, no money, and no means of getting Lerato to the national park.

‘Oh yeah? How are you going to do that?’ She had seen right through him.

‘I’ll find a way.’

‘Well, good luck with that. My dad wouldn’t let me go anywhere with you anyway – not with any boy, I mean.’ At that moment Lerato’s phone had begun to play a rap tune. ‘Speaking of my dad, just let me get this. I called him to see if he can come pick me up now.’

It was an odd day at school. Their teachers had just called an impromptu strike over wages and school was finishing before lunch. Themba walked to and from school, seven kilometres each way, but Lerato’s dad dropped her at school every morning and collected her each afternoon, in a shiny new black BMW.

She had answered the phone, stood and walked away to talk to her father. Themba had felt like a piece of him had been chopped off as she left, even though she was standing just a few metres away.

‘What? No, I understand. OK. There’s someone who can help. He’s a good guy, Dad, honest. No, Dad, he’s not like other boys, he’s kinda nice. He’s totally not the sort of guy who would try anything, trust me, please. Here, you can talk to him.’

Themba looked up at Lerato as she returned to his side. He didn’t know if he’d heard right. ‘What is it?’ he mouthed to her.

She lowered her phone. ‘My dad can’t come pick me up or send his driver because he has some business meeting he needs to attend. It’s urgent and he can’t get out of it. He’s very protective of me. I have to get a taxi home, but he’s paranoid something will happen to me. Here.’ She thrust the phone into his hand.

‘Hello?’ Themba had said tentatively.

‘My daughter says you can be trusted, is that correct?’ the deep voice on the phone said, no preamble, no greeting.

‘Um. Yes. Yes, sir.’

‘Listen carefully to me, boy. Do you know who I am?’

Themba swallowed. ‘Yes, sir. Mr Bandile Dlamini.’ He wasn’t sure what else to say, so added, ‘a very important man.’

‘I don’t need your flattery, I need your help. If my daughter is harmed in any way, trips over, stubs her toe or has a hair out of place, I will make it my business to hurt you. Do you understand me?’

Themba understood the soft, menacing tone perfectly. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘Put my daughter back on the line.’

Lerato had reassured her father that all would be fine, and that Themba would see her home safe. Lerato’s mathematics teacher was the last to leave the school and she had stayed back to explain something to Lerato, her favourite student. Now Themba was waiting, feeling sick to his stomach with apprehension, and maybe something else.

‘I’m not hanging around any longer,’ Bongi said.

‘OK, fine. See you tomorrow,’ Themba replied.

Bongi punched him in the arm. ‘Man, you’ve got it bad.’

‘I do not.’ Even as he said the words, Themba knew they were a lie.

Bongi walked away, waving his hand in the air without looking back. Themba looked at his shoes. The toes were scuffed. He licked a finger and wiped them, then rubbed each on the backs of his trouser legs. The shoes didn’t look much better; there was no disguising the fact that he was poor. He sighed. Lerato’s father might be happy for him to shepherd his daughter home, but he would never allow Themba to take her out on a date or anything like that.

‘Hi. I’m done.’

Lerato’s voice was more melodious than any bushveld bird he had heard. His heart felt like there was an invisible hand wrapped around it, squeezing.

‘OK,’ he croaked. ‘Let’s go.’

As he walked out the gates to the road to where they would pick up a minibus taxi, with the prettiest girl in school by his side, Themba felt like the luckiest boy alive. Part of him felt a little miffed that Lerato had told her father he could be trusted because he was some kind of harmless nerd, as opposed to the other boys who strutted loud and proud in front of her to try and gain her attention. But he consoled himself with the fact that she hadn’t suggested anyone else to escort her. His days of pretending to be a tough guy were through. Even though the taxi would be packed with a dozen or more people it would be like a limousine compared to his normal daily commute. He looked up to the sky to say a quick, quiet prayer of thanks, and noticed a helicopter.

*

Bandile Dlamini hoped his daughter would be all right. Since his wife, Siphokazi, had died in a car crash two years earlier, he had been paranoid about Lerato’s safety. They had wanted more children, but Siphokazi had been unable.

‘Mona market,’ he said to his driver.

‘Yes, boss. The deal is on?’

‘Yes.’

Located near Hlabisa, to the west of Hluhluwe–iMfolozi Park, the Mona market was a place where animal products and various other sources of muti– traditional medicines – were traded, legally and illegally.

In the boot of the BMW was a bag full of several hundred thousand rand. He wiped his palms on the fabric of his tailored suit pants. He wasn’t really going to a business meeting, as he had told his daughter.

He was going to the market to buy three rhino horns taken from animals illegally poached in KwaZulu-Natal’s national parks.

Chapter 3

Mike Dunn stopped his Land Rover Defender on the side of the road. He reached into the back and took the gun case from the floor, unzipped it and removed his .375 hunting rifle.

His office was the bush and much of his time was spent in Big Five country, among lion, leopard, buffalo, rhino and elephant. He carried the Brno rifle for protection, and while he was outside the nearby Hluhluwe–iMfolozi Park he didn’t dare leave the rifle in the truck while he was gone from it. No one would be mad enough to steal a Defender, but a heavy-bore hunting rifle was highly sought after by rhino poachers or the criminal gun dealers who supplied them.

Mike smelled the carcass before he saw it. The sky was clear and there was no noise around him save for the swish-swish of his canvas gaiters, a protection against ticks, as he strode through the long grass of the uncultivated field. Not a breath of wind blew. His khaki shirt was soon sticking to him.

He was ready for the sight that would match the terrible smell. The stench was like an invisible wall, one he couldn’t pass through. With each step he moved deeper into it, became part of it. Mike was no stranger to death. He could see it now, a trident of white ribs sticking up above the grass, and sound had come to the scene in the form of the hum of gorging blowflies.

Mike wiped sweat from his eyes. He knew what he was walking into, the terrible sight that awaited him, but knowing, preparing, was not the same as armouring.

At first he thought all the birds were dead, but a strangled squawking noise attracted his attention. He jogged to a whitebacked vulture that was somehow still alive. Seeing him it tried to hop away, but it had lost its sense of balance and stumbled over its talons and fell, its giant wings sprawling outwards. It was gagging and convulsing, trying to regurgitate the poisoned meat. Its head was drawn back, its neck bent as the painful process of dying continued.

Mike worked the oiled bolt of the Brno, chambering a round. He knew from bitter experience there was nothing he could do for this magnificent creature. He took aim and the gunshot echoed across the veldt.

He walked back to the carcass and felt anger displace the sadness when he saw the first body. As he knelt beside the vulture he indulged himself in a brief fantasy of what he might do if he caught the people responsible for this in the act. If one of them was armed and raised a gun to him, he would be within his rights to …

No. It didn’t help talking about shooting poachers, nor the people who used the end products. It was the same with the current epidemic of rhino poaching; hunting poachers, arresting them, or even killing them if they opened fire on the national parks and security forces was only one part of the fight. It was Mike’s view, stated ad infinitum at conferences, in media interviews, and around the fire at braais, that the war on poaching could not be won in the African bush; it had to be fought and settled in the mind.

It was easier said than done, however, the business of convincing a Vietnamese businessman that rhino horn was not a fitting status symbol or a cure for cancer, or persuading an aspirational African believer in traditional medicine that sleeping with a vulture’s head under his pillow would not guarantee him success at a job interview or a win on the national lottery numbers.

Mike went to another dead bird – he estimated there had to be at least two score of them. His shoulders sagged and his heart hurt. He dropped to one knee, the butt of his rifle resting in the yellow grass. This one, and ten others in close proximity, had been beheaded, probably just before the helicopter arrived overhead. Blood from the magnificent creature’s neck mixed with the red earth of Zululand. It was ever thus. Mike looked up and scanned the grassland around him. He saw no movement, but when he took another look at the lifeless birds scattered around the remains of the cow he saw that several, a dozen or more, still had their heads on.

‘Where are you?’ he said, addressing the heat haze at the edge of the clearing. Whoever had done this, whoever had killed this cow or, more likely, dragged the roadkill from the tar to the grass then laced it with Carbofuran or some similar poison, was probably not far away. Mike’s fingers tightened around the oiled wooden stock of the rifle until his knuckles showed white through his deeply tanned, sun-creased skin.

He stood and scanned the tree line, but there was no sign of movement. Mike walked to the hollowed-out remains of the cow. The vultures had gutted and stripped it with their trademark frenzied efficiency. He knelt again to examine it more closely, and his eyes locked onto a few purple granules. It was definitely Carbofuran. The poison was used by farmers to combat pests and aphids, but it was also harmful to birds and animals. It was deadly enough to take down a lion – farmers in Kenya had been using it against predators, illegally, for years. The poison even had a nickname among poachers, ‘two-step’ – the distance a victim would cover before succumbing to the deadly substance.

Mike took out a plastic zip-lock bag from the back pocket of his shorts and a pen from his shirt. He used the pen to scoop some of the poison into the bag. With luck a lab might be able to trace its exact make and source.

The Zulu called vultures Inqe, which meant the one that purifies the land. They did nature’s dirty work, clearing up the remains of kills that had provided nourishment for others. They prevented the spread of disease and did not prey on live, healthy animals or people. In short, they did nothing wrong, and a hell of a lot of good. Man repaid the good work Inqe did by vilifying and poisoning them.

Mike felt angry, sad, dejected, and, at the same time, galvanised. He walked around the scene of death, eyes down, looking for spoor. He’d tried calling his contact at Mtubatuba police station, Sergeant Lindiwe Khumalo, but couldn’t even get through to the switchboard. Mike had heard on the news that there’d been a bomb blast in Durban. He cared little for international politics or politicians, and while he was saddened by the loss of the American ambassador and her bodyguards, his war was here, in the blood-spattered grass, not in the global war against terrorism, or a clash of religions.

There were parallels, though, he mused as he checked the ground for footprints, tyre tracks and other signs of the people who had committed this mass killing. The poachers killed animals and birds in order to prey on the unproven beliefs of their customers; terrorists invoked religious beliefs to encourage young men and women to die for something ethereal, a promise of a better life after death. It was all crazy.

He had learned to track as a youngster from his father, who had hunted, although Mike himself had never had an interest in hunting beyond shooting a couple of impala for the pot. From an early age he’d set his sights on a career with the old Natal Parks Board. He’d managed it, and had thought he’d have a job for life in the bush. But change had come to South Africa in 1994 with the end of apartheid and the election of Nelson Mandela. Mike had known, like the overwhelming majority of his peers, that their lives would change.

Unlike some, he hadn’t been bitter when the axe fell. He was one of the lucky ones, who had completed a university education in the pursuit of his love of wildlife. When he was made redundant, eventually, from the renamed Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, he left as one of the country’s foremost experts on birds of prey, especially vultures. He had found a job with an NGO; money from foreign donors and South African businesses with a conscience kept him in work, but did little to stem the bloodshed. As depressing as his work often was he appreciated the benefits that came with it. He travelled southern Africa, working with various national parks services, counting nests and tracking birds with GPS devices. He trained police and parks officers in what to look for at the scenes of vulture killings and sometimes accompanied them on operations. He gave lectures and media interviews and worked with other researchers and volunteers. He was his own boss and his funders were grateful for the publicity his work generated.

He would need to collect the birds that had not yet been beheaded. Mike scanned the tree line again. He was sure that whoever was responsible for this barbaric crime was nearby, probably watching him, waiting for him to leave.

He stopped at another dead vulture. This one was a lappetfaced, bigger and more powerful than the white-backed vultures around it. With its wickedly curved beak and strength it was the ‘can-opener’, capable of opening the toughest skin. It fed first and, in this case, had probably been one of the first to die. He stroked its pinkish neck. His student volunteers were usually surprised at how soft yet strong that skin was. He rarely saw a nick or a scar despite the fierce competition of sharp beaks on a kill.

Mike raised the rifle again and started to walk towards the bushes, his senses ratcheted up a few levels, the hairs on his arms prickling. He’d taken no more than a dozen steps when his phone vibrated in his pocket.

He stopped and thought for a moment. If there was a poacher there, and he was armed, he should at least tell someone what he was doing. He pulled out his phone. He didn’t immediately recognise the number, but hoped it might be the police. ‘Mike Dunn.’

‘Mr Mike, it’s Solly.’

Solomon Radebe was a sixty-something-year-old ex national parks ranger from Mtubatuba. He had been invalided out of the parks service after a buffalo had charged him and trampled his right leg, breaking it in several places. He walked with a limp. A lifelong protector of wildlife, and as straight as they came, Solly had worked with Mike before his retirement and still kept in touch; he had tipped Mike off in the past about the illegal trade in vulture heads.

‘Howzit, Solly?’

‘Fine, and you?’ he replied.

‘I’m fine,’ Mike said, and with the protocol out of the way it was safe to say, ‘what can I do for you, Solly?’

‘There is something going on at the Mona market today, right now. This is important, Mr Mike. There is a big man here, fancy car, bodyguards. Something is about to happen.’

Mike had never had reason to question Solly’s instincts or his information. Solly had noticed that the buffalo that had charged him was about to attack, and had put himself between another trails guide and their party of tourists to protect them from the charge he saw coming. He’d shot the buffalo, fatally wounding it, but the momentum of its charge had carried it onwards and over Solly’s body. He’d received a commendation for bravery.

‘Something like what, Solly?’

‘A big deal. I have seen this man before; he’s an ex-politician. I think he is here to buy or sell something very valuable.’

‘How valuable?’

‘Enough to warrant him bringing a bodyguard as well as a driver.’

‘You’re watching them?’

‘I am, Mr Mike. I don’t want to approach them myself.’

Mike wanted to spend more time at the cow carcass, collecting evidence and photographing the scene. However, Solly’s instincts were good and he was fearless. Mike had the option of preserving the scene of one wildlife crime or preventing another.

He went back to his truck and from the rear he took an anemometer, a cigarette lighter and a five-litre can of fuel he kept for cases like this. With the rifle slung over his shoulder he jogged back to the carcass. He held up the wind-measuring device and checked that the direction and speed were in his favour. They were; the wind was blowing back towards the road, and the breeze was only a couple of knots. Even better, the grass on the other side of the road had been recently burned.

Mike set down the device, fuel and his rifle and set to work dragging the dead vultures back to the carcass that had killed them, piling dead upon dead. When he was done, his clothes soaked with sweat, he splashed half the container of fuel over the grisly mound. He lit a handful of dry grass and tossed it; the pyre erupted with a whoof.Ideally, he would have had people here to watch that the blaze didn’t get out of hand, but at this time of day he was sure the wind wouldn’t change. The grass would catch, but the fire would stop at the roadside and burn itself out. Mike spared a look back to the trees and hoped the bastards who had done this were watching the rest of their profits go up in smoke. He gathered his things and jogged back to the Land Rover.

It wasn’t far to the Mona market and he pushed his Land Rover as close to the speed limit as it would let him. Villages and bare, overgrazed hills flashed by. When he came within sight of the stalls, but not too close, he pulled off the road and parked. Solly walked down the road to meet him.

The market itself ran along both sides of a back road, a linear collection of ramshackle stalls and huts made of timber, corrugated iron and other cast-off building materials. Here and there were a few more substantial shelters of mud brick. Some sellers plied their wares on makeshift shelves in the open. Side alleys had sprawled from the main road and Mike knew it was usually in these back lanes that the illegal products were to be found. Solly led him to the rear of a brick building, a shebeen, a local bar.

The market was quiet now; the end of month rush, when people were paid, had just passed and many of the stalls were closed, wrapped shut against the elements with fraying canvas and plastic sheeting. A dog, all ribs and mange, trotted down the street searching for scraps. A woman selling tomatoes and cabbages cursed it in Zulu.

After they’d exchanged greetings and shaken hands, Solly said: ‘I got closer to them, and I recognised the big man, the one who is obviously in charge. He was wearing dark glasses, so I couldn’t be sure from a distance.’

‘Who is he?’

‘Bandile Dlamini.’

Mikesworequietly.‘Theformerpoliticianturnedentrepreneur?’

Solly looked left and right. ‘Yes. He talks a good deal about protecting wildlife and the fight against rhino poaching.’

‘Then what’s he doing here?’

Solly shrugged. ‘I don’t think it’s a photo opportunity for the local media, or a campaign rally. He’s gone back to his car now. He has a driver and one other man, who looks like a bodyguard.’

‘Why does a businessman need a bodyguard?’ Mike asked. ‘It’s not like he’s a government minister who’d warrant protection.’

Again Solly looked around, checking no one had moved into earshot. ‘I’ve heard talk about him. Before he got into politics, back in the days of the struggle, he moved guns and explosives for the ANC, but people said he also supplied criminal gangs. They say he was involved in car hijackings as well, not stealing the vehicles himself, but running garages where stolen vehicles were stripped and resprayed. But this was years ago.’

Mike had read Dlamini’s tough talk in the newspapers, and had met him once at a conference on rhino poaching, but he hadn’t had time or the opportunity to form his own opinion of the man. ‘Let’s take a look around.’

They walked out from behind the shebeen onto the dusty road that ran the length of the market.

Most of the people selling goods greeted them both, but every few stalls someone would retreat further into the shadows at the rear of their tin hut, avoiding eye contact with Mike, perhaps thinking he was police or national parks – or they recognised old Solly. As they passed one stall Mike glimpsed a giraffe skull with dried skin still stretched across the bone, and a set of hippo tusks beside it. The seller tossed a blanket over his wares, but Mike didn’t care about him right now.

Solly put a hand on Mike’s forearm and pointed down the street. Mike saw the black late model BMW sedan with the tinted windows, a heavy-set man in a leather bomber jacket and sunglasses leaning against the bonnet.

‘That man is the driver,’ Solly said.

The rear door on their side opened and a man got out.

‘That’s not Dlamini,’ Mike said.

‘The bodyguard,’ said Solly. ‘Dlamini is inside in the back seat.’

The driver pulled the keys from his pocket and pressed the boot release on the remote. The boot popped open and the bodyguard, dressed in jeans and a grey hoodie, took out a hessian bag before closing it again.

Mike and Solly moved between two stalls, where they were out of plain sight but could still track the man with the bag. He crossed the road and came their way, to a small shack about a hundred metres up the street.

‘Let us go behind the stores,’ Solly said.

Solly led them to the rear and they moved cautiously but quickly along the line of stalls. Away from the street chickens foraged in garbage, women cooked pots of papover small fires, and young men brought more stock for the various sellers.

‘It is this one,’ Solly said, then put his finger to his lips. He and Mike moved quietly to the rear of the stall.

Mike let Solly translate, though his Zulu was almost as good as the old ranger’s.

‘The man with the bag is selling something,’ Solly said. ‘The other man is asking what it is.’

‘Inqe,’ Mike whispered, before Solly could translate the next sentence. ‘Vulture heads.’

Mike took a deep breath to try and still himself. He wanted to kick the ramshackle back door of the hut in and grab the man with the bag and throw him to the ground. He would probably be armed, but Mike had a gun as well.

Solly put his hand on Mike’s arm again. ‘We must wait.’

Mike exhaled. ‘You’re right. Listen.’ Mike put his finger to his lips to tell Solly he could understand what the men said and didn’t need any further translation.

The bodyguard was saying the vulture heads were fresh, not yet even dried. The stallholder asked how many he had. ‘Ishumi nanye.’

Eleven. Mike remembered the headless birds he had found at the site just outside of Hluhluwe–iMfolozi, where the cow had been poisoned – the exact same number. If it hadn’t been for the helicopter tracker scaring away many birds with the helicopter, there would have been more. It was no coincidence; these had to be the heads of the birds he had burned.

The men argued over the price, with the stallholder eventually offering an amount acceptable to the seller. It was a tidy sum, but Mike thought about Dlamini, in his big black sedan waiting across the road. Vulture heads were worth good money, but good enough for a high-profile man such as Dlamini to risk hanging around in public while his minion did the trade?

Inside the shack the stallholder told the bodyguard that he needed to go fetch the cash from elsewhere; it made sense the man would not keep a stockpile of money in his stall or on himself, in case of theft. Solly and Mike backed up between the shop and its neighbour, as they heard the rear door creak open.

Mike reached behind his back and drew his pistol. As the stallholder came into view he took three steps forward, wrapped his hand around the man’s mouth from behind and rammed his pistol into the man’s temple.

The stallholder was wide-eyed, but didn’t struggle.

Solly unthreaded the belt from his trousers and, with Mike keeping the gun on the man and his finger on his own lips to warn him to continue to be quiet, Solly trussed the stallholder’s hands behind his back. Mike took a cleaning rag that was hanging on a wire fence between the huts to dry and stuffed it in the man’s mouth. They lowered him to the ground, on his knees. Solly produced a knife from inside his threadbare suit jacket and held it to the man’s neck. Mike returned to the rear of the shack.

He cocked his head, moving along the wall of the shack to the back door. There was movement inside. Mike paused, felt the tension and adrenaline firing up his nerve endings. The man Solly was holding a knife to had been about to commit a crime, but he had not handed over any money. Mike wondered if they had gone too far too soon, but the thought of those eleven headless vultures, and the other birds he’d seen slaughtered and nests destroyed enraged him. This, he was sure, went beyond the killing of birds for traditional medicine. This deal was a curtain raiser.

Mike glanced back at the bound man. He looked terrified. He would not be a dealer in rhino horn; his market was local people who wanted a talisman or a potion to improve their lot in life, not Vietnamese businessmen half a world away who wanted to avoid hangovers or impress their commercial contacts.

The back door of the shack creaked as it swung open.

Mike moved to where Dlamini’s bodyguard was exiting, probably looking to see where the stallholder was, and noticed him reaching under his hoodie. From a shoulder holster under his left arm, the man drew a black pistol. He had his back to Mike, who moved forward, raised his arm and smashed the butt of his own gun down on the back of the man’s head. The bodyguard crumpled to the ground. Mike straddled the man and reached down, snatching the pistol from his hand and putting it in his pocket.

The man moaned and writhed on the ground at the rear of the stall, not out cold, but stunned. Mike bent down again and snatched up the hessian bag the bodyguard had dropped beside him. Inside he saw the pinkish-grey heads, the glassy eyes, the hooked beaks. Mike gave the man a kick.

‘Who are you?’ the man croaked.

‘Shut up.’ Mike pointed his gun at him. ‘What’s your boss doing here?’

‘Who?’

Mike kicked the henchman again. ‘Dlamini. Don’t tell me he’s here just to oversee the sale of some vulture heads.’

The man spat. ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about, and if you’re not police then get off me.’

‘You’ll wish I was the police once I finish with you.’

‘Hey,’ Solly called, ‘let’s just wait for the police.’

Solly was right, but Mike was angry. The bag of vulture heads had incensed him. ‘There’s more to this than just the heads.’

‘I agree,’ Solly said, ‘but we are not the law.’

Mike ignored the older man’s words of caution and addressed the henchman. ‘If you’re delivering the vulture heads for Bandile Dlamini then you’re just a courier, not a serious criminal. Tell me where you got them from and I’ll put in a good word for you when the police arrive.’

The man spat blood. ‘I’ll tell the police what you did to me and I’ll charge you with assault, white man. Go fuck yourself.’

It wasn’t in Mike to torture the man any further, beyond the kicking he’d given him, but he needed him to talk. He picked him up by the hood of his top and pushed him around the corner of the stall to where the stallholder was sitting, bound and gagged. ‘OK, how about I let you go free. I’ll take the heads, and this guy,’ he gestured to the stallholder with his pistol, ‘can tell the cops how he was never going to buy any vulture heads and instead cooperated fully with the police and national parks officers. You get to go back to Dlamini and tell him you lost the heads and didn’t get the cash. How about that?’

The man’s eyes darted from the stallholder back to Mike, and then to Solly. Seeing he’d get no sympathy from the old ranger he looked at Mike again. ‘What do you want?’

‘I asked you already,’ Mike said. ‘Who’s your boss?’

‘Those vulture heads weren’t mine. I was just making a delivery.’

‘A delivery for who?’ Mike replied.

‘Fuck you. I want a lawyer.’

Mike leaned over the man and again pressed the pistol to his head. ‘You think I won’t shoot, right?’

The man glared back at him. ‘I know you won’t, and I’m going to see that you’re charged.’

Mike looked to Solly. ‘Take the stallholder away, out of sight. You don’t need to see this.’

Solly hesitated. ‘Mr Mike …’

‘Go. No one will miss this piece of shit, certainly not his boss, since he lost both the goods and the money. Leave me to finish this. He is no use to us any longer and it’s time I sent him on his way.’ Mike took his captive’s pistol from his pocket and passed it to Solly.

Solly took the firearm, lifted the stallholder up by his bound wrists and pushed him towards the street.

‘Please,’ the man at Mike’s feet said. Mike had never had any intention of executing him, but he had the satisfaction of seeing the fear in his face.

Solly, who seemed unable to tell if Mike was bluffing or not, gave him a worried look. ‘What do you want me to do?’

‘Keep that guy under wraps somewhere. Call the police. They’re busy with a load of other kak, but they’ll get here eventually. Don’t let Dlamini see you’ve got our shopkeeper here, or he might drive off. We want him as well.’

‘You’ve got this all wrong,’ the captive said.

The man cast his eyes towards Solly, but the ex-ranger had turned his back on them, probably with a measure of disgust for both of them.

‘Solly can’t help you, only I can.’ Mike raised the pistol so it was pointed between the man’s eyes. ‘And right now, we could be the only two people left in the world. Say a prayer.’

The man licked his lips, quick, like a snake. ‘Wait. There’s more at stake here than the heads.’

Mike looked over the barrel of the gun. ‘Like what?’

‘Bigger stuff than vulture heads.’

‘Tell me.’