Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Palémon

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Les enquêtes de Mary Lester

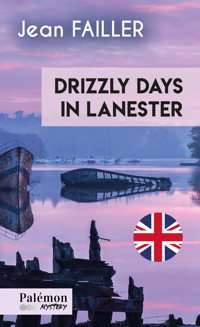

- Sprache: Englisch

"Trainee detective constable Mary Lester has been sent to Brittany’s great Southern seaport, Lorient.

A tramp drowns in the river Scorff, a supermarket manager vanishes into the air, juvenile delinquents go in for a bit of chainsaw-powered breaking and entering…

For detective constable Marc Amedeo, this is just uneventful daily routine. Peace and quiet rule in Lorient police station… or did so until Mary Lester starts knitting these apparently trivial incidents into a full blown multiple murder case!

Intrepid investigator Mary Lester is the heroine of a series of 64 best-selling novels by

Jean Failler, who sets his mysteries in towns all over Brittany. In the last thirty years, he has sold 4 millions copies of the Mary Lester books, several of which have been dramatized on French TV. "Drizzly days in Lanester" was his second novel published in English, after "Mayhem in Saint-Malo."

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jean Failler was born in Quimper where he has lived ever since. His childhood dreams were fed by the seafaring tales of his grandfather, a remarkable storyteller and professional fisherman who used to takes him aboard during the holidays.

For 20 years,

Jean Failler worked as a full-time fish-monger but, somehow, he still managed to write 16 plays (5 staged) and several short stories, children’s books and historical novels. After selling his fish-monger’s shop,

Jean Failler was at last able to fully devote himself to his passion and has graced us with 63 Mary Lester investigations where good humour and intrigue are our travelling companions throughout Brittany, all with that special tangy flavour of sailor-borne irony.

Anne Pietrasik was born in 1952 in London. A translator since 1989, she lives in Riec-sur-Bélon, Brittany

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 190

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Couverture

Page de titre

Carte

With thanks to:

Pierre DELIGNY

Nicole GAUMÉ

– JF –

Linda LEE

David PEARCE

Danièle LARUELLE

– AP –

CHAPTER I

The body of Maurice Toussaint, also known as Mo or Winklestar, depending on the degree of intimacy one might have had with the deceased, was found at low tide by Aimable Maugracieux, master gunner, presently retired.

If it hadn’t been for the strap of his carpet-bag, Mo, now spread-eagled on the black muddy bed of the river Scorff, right in the middle of the East India Company’s log dock, would long have drifted out with the ebb tide.

However, the strap had got caught around one of the old worm-eaten stakes that used to hold in the ship builders’ lumber, left there to soak, tide-in, tide-out, for several months. This practice aimed to prepare these landlubbers to their future element, the sea, where, once assembled by virtue of Man’s genius, the keels, ribs, timber heads, planking and one thousand other pieces cut up by the carpenters of the nearby Arsenal would become warships.

For his last voyage, Mo had moored himself to these stakes, initially designed to hold other trunks than human.

Aimable Maugracieux stops, freezes, and swears in front of his macabre discovery. “Bloody hell!”

He approaches the deceased gingerly, as if ring some dirty trick.

When alive, Winklestar had been quite harmless. This gentle vagabond’s ambition had been restricted to two very definite objectives: finding something to drink when he woke up, and sleeping when he had drunk.

This time, he had certainly drunk, like a fish you could say, except that the beverage had been most unusual for him: water! A substance quite foreign to Mo, whether for internal or external use. Moreover, this was salt water. At last a liquid that wouldn’t give him a hangover as, you’ll agree, hangovers usually hit you when you wake up and that’s something poor Mo certainly isn’t going to do for a long time.

Totally harmless when alive, Winklestar doesn’t look very fearsome now he’s dead. But… you never know. Aimable Maugracieux’ snub nosed face suddenly crinkles with annoyance. He’s going to have to report this to the police, and that means hassle: questions, statements, in other words, a considerable waste of time. Nothing good is going to come out of all this.

On top of that he’d planned to pick some winkles for his supper, definitely not on schedule any more. And will Aimable Maugracieux ever be able to enjoy his winkles any more? Not so sure. The few fair sized specimen presently exploring the body’s hollowed orbits aren’t exactly appetizing.

Ironically, winkle picking had been Mo’s main trade, hence his nickname. With an expertise borne from long practice, he’d tracked them down beneath the kelp growing in the mud flat. When his plastic bucket was full, sometimes earlier when thirst or hunger took priority, he sold them in Lorient or went to the local fishmonger’s and traded them against a litre of red wine, his only currency where bartering was concerned.

He would then take the metal gangway of the railway bridge over the Scorff which stood 15 metres high, an uncomfortable height when the wind was growling through the structure’s metal crosspieces and the Paris-Quimper train was crawling noisily over it.

Mo wasn’t the only one to use this short-cut. Quite a few people from Lanester do so regularly, overcoming ugliness, windiness and giddiness all the more easily that it spares them the 2 kilometre detour upstream to the Pont Saint-Christophe1.

Yes, Maurice Toussaint made a living off the winkles and now the winkles are living off him. Mother Nature’s implacable law: eat or be eaten…

A few green crabs scuttle away on hearing the loud sucking noise Aimable Maugracieux’ boots make as he ploughs through the sticky mud. Two fat herring gulls perched on a neighbouring stake and casting longing glances at the body fly away heavily, protesting with loud raucous cries. They land a few metres away, never letting their cold beady eyes off this great lump of meat that Mother Sea, in her infinite goodness of heart, has thoughtfully provided.

He’s dead, Aimable Maugracieux perceptively notes. What does he think, this master gunner? That Winklestar is there for the fun of it?

Aimable stays there a while, pondering on what he should do, arms hanging, undecidedly balancing from one foot to the other, the mud gurgling away with each change of footing. At last, having more or less established that this here individual doesn’t require urgent care, he tramps off to warn the authorities.

Maugracieux phones the cops from a telephone booth standing by the dockside and it costs him one franc fifty. A franc fifty at his expense, of course. At least the booth isn’t out of order, thank God for small mercies! They often are nowadays, and sometimes they don’t put your call through but won’t give you your money back either. It had already happened to Aimable Maugracieux. He’d even been all the way to the central post office to complain. But do you think he got a refund? No way!

“For one franc,” the postwoman had sneered. Aimable would have quite happily slapped the cheeky old cow.

The other idiots in the queue had stood up for the old bag as well. “A franc! Does one waste a hard-working civil servant’s precious time for one franc!”

So he’d given up and left, grumbling to himself. A franc is a franc, Aimable thought. On top of that, it was a matter of principle, which made this franc doubly symbolic. But principles have gone to pot in this country; that’s why France is in such a sorry state these days. Oh, how he would have loved to hold these protesters under his thumb when he was deputy instructor in the barracks of Hourtin. By God! He would have made them crawl. The same for all these young wankers who hang around all day and vandalise phone booths at night.

The Police Secours phone number is eventually answered by an unenthusiastic police officer who promptly asks him where he is calling from before hanging up on him. He does call back though. This, he explains, is current policy to deal with practical jokers. A practical joker? Aimable, a practical joker? It’s them who have to be joking.

Out there, near the body, the ring of gulls is tightening in. In a while, the boldest will rip out a piece of flesh and trigger the squawky scramble for the spoils. If them stupid cops don’t get a move on, there will only be bones left to see…

A train crawls slowly across the metal bridge, steel grinding against steel. The lit-up windows neatly outline the cosily seated passengers. Further down, grey warships are barely visible against the equally grey sky and water. Near the Pont Saint-Christophe, small boats are lazily riding at anchor in the channel current. The Boulevard Normandie-Niemen running alongside the river Scorff is deserted, the silence only broken by the occasional car swishing by on the wet tarmac.

Suddenly, things get moving. First comes the white police car with its blue emergency rotating light and howling two-tone siren, closely followed by the red firemen’s van, hurtling down on ill-treated tyres, and then, bringing up the rear, the ambulance.

Aimable chuckles bitterly. An ambulance, the idiots have brought an ambulance! For a stiff that’s already half gobbled-up by the winkles. His face takes on an even uglier expression than usual at the thought of such waste. Oh, they’re not too concerned about undue expenses… like all those who aren’t the payers.

The coppers approach. There are two uniformed men and this woman. What’s this bird doing with the cops?

She approaches Aimable Maugracieux. “Detective constable Mary Lester. Is it you who phoned?”

Dumbfounded, Aimable mumbles a yes. A female copper! Whatever next?

“Where’s the body?”

Aimable nods towards the mud flat. “Out there.”

“You haven’t touched anything, have you?”

“No.”

“Fine, let’s go.”

The woman copper turns around to give out her instructions. The firemen get a stretcher out of their van whilst the ambulance men light up a cigarette and lean back against their ambulance. There’s no way they’re going to plod through the mud in their nice clean uniforms.

Practical-minded, the detective constable (What do you call them when they’re female? Constableresses?) pulls plastic carrier bags over her shoes. The uniformed men don’t take the trouble and are soon up to their ankles in it, swearing under their breath. There’s going to be some serious shoe cleaning at the police station that evening.

Aimable ambles along, telling them in a few rough words how he found the body. Mary soon realises that there’s no evidence left to find. She signals to the firemen that they can get on with it. The body is hoisted onto the stretcher, its stiffened and therefore unbendable arms splayed out on both sides, and late Maurice Toussaint heads for the morgue.

Aimable is about to go home when the woman cop calls out: “You’re coming with us, Sir.”

Aimable jibs. “But…”

“You’ve told us everything, I know, but I need to take down your statement.” And, reassuring: “It won’t take long.”

It won’t take long. Well that’s a good one. Half an hour he’s been stuck in the police station waiting room. And for what? To say he went out to check his boat’s mooring before the spring tides and that, on his way back, he’d suddenly fancied a few winkles to start his supper with. That was all he had to say… well, not quite. He could’ve added that he thought it was an absolute shame, yes a shame, that tramps’ bodies were to be found right in the city centre.

*

“So, you knew the victim,” Mary Lester asks, playing with her ball pen.

Click, click, click… goes the pen as she pushes the button in and out. This both irritates and fascinates Aimable. His eyes are riveted to her hands. Click, click, click…

He starts, and grumbles. “I knew him… I knew him… hang on a minute! What did you say his name was?”

“Toussaint. Maurice Toussaint.”

“That’s right. And the others called him Winklestar.”

“What others?”

“Well… his pals… You know… I mean the other guys he chatted with on the shore.”

“What guys?”

“I don’t know. Guys from the Arsenal, or from the foundry… Quite a few of them own a small boat. Winklestar used to pick winkles, that’s where he got his nickname from. Sometimes he gave people a hand to haul in a boat and they brought him a drink. That’s all.”

Mary Lester looks at him straight in the eyes. “Are you sure?”

“Sure of what?” Maugracieux says, exasperated.

“Sure, that’s all.”

“Well, that’s just what I’ve told you, isn’t it!”

Click, click, click… (Is she ever going to stop with that bloody ball pen? She’s really getting on my nerves).

“Did he help you?”

Maugracieux flares up. “Never! I don’t need help from people like that.”

“But you did speak with him, didn’t you?”

“Never, I tell you. Guys like that, well, I… I…”

Mary Lester waits for him to finish his sentence. Click, click, click…

“What do you mean by guys like that?” she asks as nothing is coming.

“Well, you know,” Maugracieux splutters, “tramps…”

“You don’t like them, do you?”

“Can’t stand ‘em,” Maugracieux spits out. “Dirty drunken parasites, filth, they ought to be… to be…” He’s stuttering with indignation.

Slyly, Mary helps him on. “To be what, Monsieur Maugracieux? Shot?”

Suddenly grasping the abysses looming ahead, Maugracieux rapidly shifts into reverse.

“Hang on a minute, don’t you go putting words into my mouth.”

Click, click, click…

“I’m not, Monsieur Maugracieux. You said it.”

“I didn’t say anything of the sort.” Flustered, Maugracieux adds: “all I said was that I couldn’t stand them and that…”

“And that what?” Mary Lester probes unrelentlessly.

“That it shouldn’t be allowed. There!”

“That’s not very far from getting rid of them…”

“Wait a minute,” Maugracieux says rising from his chair, “I haven’t killed no one!”

“We’ll check, Monsieur Maugracieux.”

“Do you mean you actually suspect me? But the bloke probably just drowned himself. Half the time he was blind drunk anyhow. He could easily have slipped in the mud.”

“We’ll check,” Mary Lester repeats.

“If I’d have known,” Maugracieux groans, “would I have turned a blind eye and steered clear of him! At this time, I’d have been nice and cosy at home. These tramps are a bloody nuisance, even dead they’re nothing but trouble.”

Mary Lester doesn’t react to this last comment of Aimable Maugracieux. She seems to be daydreaming.

Discreetly hiding a yawn behind her right hand, she adds: “You may go home now, Monsieur Maugracieux. Could you please sign this for me?”

“What’s that,” Aimable asks suspiciously.

“It’s not your death sentence, just your statement. Do check it out first if you want.”

“You bet I’m going to read it first,” Maugracieux says, fishing a ridiculous pair of tiny metal-rimmed glasses out of his pocket and perching them on the end of his strawberry shaped nose.

In fact, he reads the whole thing through twice, just to make sure they haven’t put words in his mouth that he might regret later.

“Is this correct?” Mary Lester asks.

The confused rumble that emanates from Maugracieux and resembles a not very complimentary answer could also serve as an agreement. He bends over and, sticking the tip of his tongue out in the effort, painstakingly applies his care fully ornate signature on the form in front of him. Then, head slightly tilted sideways, he contemplates his work with a satisfied grin and, handing the ball pen back to Mary, asks: “Will that be all?”

“Yes, Monsieur Maugracieux. That will be all. Thank you very much for your cooperation.”

“You’re welcome,” Maugracieux grumbles, shrugging his shoulders.

He makes for the door sideways, like a crab, and disappears from the scene.

1 “Pont” means bridge. The Pont Saint-Christophe crosses the river Scorff between the large seaport Lorient and its suburb, Lanester.

CHAPTER II

“Wow!” detective constable Mary Lester says to the sergeant who’s been laboriously typing out Maugracieux’ statement with two fingers, “talk about sweet mouthed! Aimable, on top of that he’s called Aimable2, I don’t believe it.”

Mary Lester can’t know that Désiré Maugracieux, father of the above-mentioned, and his wife Anne, born Dagorn, tried to compensate for their unfortunate patronymic by giving their only child a first name they thought comely. Unfortunately, with his constantly surly air, Maugracieux has been bearing his first name like a cross for the past fifty-nine years.

“Aimable Maugracieux…” Mary Lester is reading the statement out loud. “Age fifty-nine, married to Francine Le Gallou. No children (thank God for that, at least the line will soon be extinct), retired 2nd-class master gunner. Indochina, Algeria… Distinguishing feature: nil… Nil, my eye!” Mary Lester says, “I would have written: distinguishing feature: loves no one or, better still, hates everybody! That’s it, hates every body. That’s an eminently distinguishing feature.”

“Not regulatory, Miss,” the sergeant says from behind his typewriter.

“You’re right, Le Moal.” Mary Lester gets up. “It’s not… Pity, though.”

*

Mary Lester is alone in her office, absentmindedly playing with her ball pen, click, click, click, when the door bursts open on Marc Amedeo. Startled, Mary drops her pen, much to the new comer’s delight.

“Did I scare you then, love?” he asks, grinning insincerely.

Mary Lester doesn’t answer. She loathes the man, this detective inspector who is supposed to help her, the rank amateur… She loathes the way he barges into her office without knocking, the way he addresses her as “love” when love has certainly nothing to do with her feelings for this Mediterranean heartbreaker, not to say pimp, who obviously expects all women to swoon at the very sight of his lordship. However, he is her superior and she has to put on a good face. So, she tries…

“Tell me, love, what’s this about a stiff turning up last night?” he asks, casually perching himself on the corner of her desk.

Mary Lester pushes her chair back and opens a drawer. She takes out the report Le Moal had typed and starts to read out loud in a monotonous tone. “The man was called Maurice Toussaint, also known as ‘Mo’ or ‘Winklestar’, take your pick. Age: fifty-five. Profession: tramp.”

“Has he been formally identified?”

“Yes, Monsieur. Everybody knew him. He was one of the local characters. He’d set up his quarters in an old blockhouse, under the railway bridge, between rue Camille Pelletan and the Arsenal wall. Apparently a harmless bugger.”

“Good old Winklestar. So, he finally went and got himself drowned.”

“Because you knew him?”

“You’d have trouble finding someone who didn’t know him,” Amedeo says. “In fact, everyone was wondering when he was going to fall in the river. It’s a miracle it hasn’t happened earlier!”

“He fell in, or was thrown in, or pushed in.”

“Wow there! Hold your horses!” Amedeo says as he stands up. “We’ll just stick with the first if you don’t mind, love. He’s been picked up option blotto so many times, he most probably shoved himself in the water all on his own like a big boy. He probably tried to use the railway gangplank, despite the warning, and, now the guard-rail’s gone…”

“Maybe. One thing’s sure, he’s dead. And another thing that’s sure is that he drowned. The autopsy reports there was water in his lungs.”

“You’ve already got the autopsy report?” Amedeo says, surprised. “Oh well, things are pretty quiet, I guess our forensic surgeon didn’t have much work on his hands. Anyhow… what else?”

“The water in his lungs was brackish…”

“Yes, well, it would, obviously,” Amedeo says impatiently. “Is that all?”

“A few none too clean wounds on his wrists and feet and a large bruise on his sternum. The forensic also mentions a 1.20g blood alcohol level. This, however, doesn’t necessarily mean he was drunk. If I believe our records, he’s often been picked up with 3 grams so, for him, 1.20g is practically sober level. On top of that he had a nearly full litre of wine in his bag.”

“Any money?”

“Forty-eight francs in his trouser pocket. A fortune for a guy like him. If his death resulted from a quarrel among tramps, his assailant would have rifled his pockets before chucking him in the river.”

“And would also have taken the bottle of wine.”

“Probably.”

“Well then, love?”

“Well then what, Monsieur?”

“What do you think of it?”

“All seems to point towards an accident, however…”

Amedeo frowns. “However?”

“However, I believe it might be wise to wait a few days before closing the case. Just in case something turns up.”

“Something turns up? Do you really believe that?”

“Well, Monsieur, you never know. Someone might have seen him fall… another tramp… Who knows? He wasn’t alone all the time.”

“No, he wasn’t alone all the time. In fact, I can even tell you he was married.”

“Married? Well, that’s a bit of a surprise, Monsieur.”

“Well, when I say married, I mean living in sin… living with a partner is probably the politically-correct expression. With Titine, Titine appleface. It’s a nickname of course. After her complexion. The red wine… As for her family name, you’ll have to ask the hospital.”

“Because she’s in hospital?”

“Yes, Mademoiselle, has been for the past fortnight. On her last bender, she fell asleep under the van of a fish wholesaler in Keroyan. The man drove off without seeing her and crushed both her legs. Talk about drunkard’s luck. Anyone else would have been killed. Not Titine. Two broken legs and she’s in clover at the hospital, full board at the taxpayer’s expense. Let me tell you, the poor guy who ran her over was hauled over the coals good and proper before the ambulance carried her away. Titine’s language is something else!”

“So we can’t rely on her testimony.”

“Neither hers nor anyone else’s. Believe me, Lester, the world of down-and-outs is as closed as a clam. Particularly where coppers are concerned. If you think they’re going to come forward to testify, you’ve got another think coming, love. We can wait, of course, if you want. Winklestar’s in his box at the morgue. He’s in no hurry… Neither are we. But the sooner you file the case, the earlier we’ll be rid of it.” Amedeo stretches and yawns. “Oh well, we’ll wait a few days if you want. There’s no rush! And, as there’s no rush, you can go to the Lanester station. Do you know where it is?”

Mary sighs. Yes, she does know. Rue Marcel Sembat, number 65. She’s already been sent there three times and the only crime she’s had to fight was severe boredom. This imbecile is probably going to add that she ought to see how a small local station works.

Sure enough, Amedeo adds sententiously: “You ought to see how a small local station works.”

*

Mary Lester is alone at the reception desk of the Lanester police station.

Squatting on the left bank of the Scorff, facing Lorient, Lanester is the working class suburb of the great Western harbour. The current crisis in the shipbuilding and foundry industries, traditional sources of employment in the Lanester area, has sent unemployment rates soaring sky high. The city centre, completely renovated, is rather attractive but the neighbouring streets are full of mean little jerry-built houses, each with its vegetable patch and cement posts strung with wire where laundry is trying to dry.

After dumping her here, detective inspector Marc Amedeo has left just like he had arrived, gustily, leaving her to cope with whatever petty larceny might turn up. Mary’s seething. If anything important turns up, it’s bound to go to the Lorient central station.

Occupying the ground floor of a modern building, the Lanester police station is stuck between a veterinary practise and a bank. If it weren’t for the Wanted signs stuck on the wall with their sinister looking mugshots, we could be in any administrative office. Not a uniform in sight. The station is manned by two plain-clothed inspectors who are there to register complaints and transfer them to the Lorient central station.

Mary Lester is sitting at the reception desk. One of the two inspectors has gone out on an investigation requested by the examining magistrate. The other is in his office. He’s typing a report. Mary can hear the typewriter’s irregular clicking.

She is definitely bored stiff. She’s read the paper through and through. Even the football section, the horse-racing column and the death notices. How desperate can you get!

Maurice Toussaint’s death is featured in the miscellaneous section:

MAN FOUND DEAD IN THE SCORFF