Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Palémon

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Les enquêtes de Mary Lester

- Sprache: Englisch

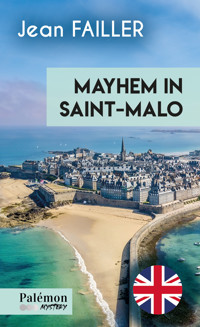

Mary Lester is a French police lieutenant in Quimper, but she has been sent to Saint-Malo to investigate a beautiful young woman’s death. The local superintendent concluded that the woman died of natural causes. Mary, who is both inquisitive and independent, thinks he is dead wrong. Not only that, but unless she takes decisive action, more lives may be lost… Intrepid investigator Mary Lester is the heroine of a series of 64 best-selling novels by

Jean Failler, who sets his mysteries in towns all over Brittany. In the last thirty years, he has sold 4 million copies of the Mary Lester books, several of which have been dramatized on French TV. "Mayhem in Saint-Malo" was his first novel published in English, followed by "Drizzly days in Lanester."

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jean Failler was born in Quimper where he has lived ever since. His childhood dreams were fed by the seafaring tales of his grandfather, a remarkable storyteller and professional fisherman who used to takes him aboard during the holidays.

For 20 years,

Jean Failler worked as a full-time fish-monger but, somehow, he still managed to write 16 plays (5 staged) and several short stories, children’s books and historical novels. After selling his fish-monger’s shop, Jean Failler was at last able to fully devote himself to his passion and has graced us with 63 Mary Lester investigations where good humour and intrigue are our travelling companions throughout Brittany, all with that special tangy flavour of sailor-borne irony.

Anne Pietrasik was born in 1952 in London. A translator since 1989, she lives in Riec-sur-Bélon, Brittany

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 286

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Couverture

Page de titre

With thanks to:

Pierre Deligny Nicole Gauméand the Saint-Malo Office de Tourisme

– JF-

Laetitia PERRAUT,who loves both books and Brittany

– WR-

Chapter 1

As the weather service had forecast, the storm came in from the west. The sky, which until then had been a light blue, barely veiled by small white clouds that floated like a downy quilt, gradually clouded up. Out over the sea, menacing thunderheads appeared, looming dark and heavy above the distant horizon.

The wind strengthened at first in short gusts, as if to warn sailors that it was time to shorten sail, and landlubbers that it was time to bring in the washing hung out to dry and to close the doors and windows tightly.

The sea, which had suddenly become very dark, began to break in short, angry, white-crested waves. In the distance you could hear it pounding the rocks of Grand Bé island and thundering on the môle des Noires, which protected the Sablons marina and was occasionally covered with foam.

Seen from the top of Saint-Malo’s ramparts, the spectacle was a grand one, but there were very few people left to admire it. Two old men hurried down the steps that would take them to the rue Sainte-Anne, where they could get back to their homes sheltered from the wind.

Mary Lester continued her walk, delighted to be alone. She thought the brewing storm suited the corsair city better than the calm weather it had enjoyed through the end of October.

The very name Saint-Malo carries such a whiff of adventure that if you were willing to forget the present century, you might almost expect to see an English squadron approaching to bombard the citadel with its cannons. And you wouldn’t have been too surprised to see the great Robert Surcouf himself emerge from the bastion de la Hollande, his brass telescope in hand, to organise the defence of the city.

There were still cannons at their stations on the ramparts, heavy masses of blackened iron borne by wooden carriages with thick, iron-rimmed wheels. And they still pointed towards the sea, from which all dangers came. Though now long obsolete, these weapons had protected the city for centuries against the incursions of the Sauzons, the hereditary enemy from that great island on the other side of the Channel.

Those arrogant Saxons had good reason for dreaming of destroying Saint-Malo. To them, it was a hornet’s nest from which daring Malouin sailors had built outrageous fortunes by plundering English merchant ships. In spite of all their efforts and their domination on all the world’s oceans, the English had never been able to defeat those outstanding captains. Surcouf, the most famous of them all, had even once boarded and seized His Majesty’s ships Triton and Kent with a crew that was outnumbered ten to one.

Surcouf’s own ship, the Renard – or at least a faithful replica – remained tied up in the bassin Vauban, ready to get underway. But the weary Renard no longer set sail except to take tourists on outings. And while she still had her cannons, they were now only used on holidays, firing harmless blanks in a roar of noise and smoke, to the delight of little children.

As Mary Lester strode against the wind along the deserted wall walk, she reflected on those glorious pages of Saint-Malo’s history.

Rain suddenly now joined the wind, borne horizontally by the gusts pelting the granite walls like machine-gun fire. Mary pulled the hood of her duffle coat over her head. Darkness was falling on the Old City with surprising speed. A couple was hugging in a nook of the Tour Bidouane, well sheltered from the rain behind a projecting stone salient. They were very young, almost adolescents, and wore fluorescent oilskins. The girl’s was pink and the boy’s yellow – or was it the other way around? It seemed to Mary that the taller of the two had long blond hair pulled back and held by a rubber band in a kind of ponytail, whereas the shorter one was cropped almost to the scalp.

She walked by, discreetly glancing sideways at the pair. Engrossed in their nuzzling, they didn’t notice, proving once again that lovers are all alone in the world, and could see nothing except each other. Didn’t they realize that it was raining and that a squall was about to hit?

Because the squall had certainly arrived. By walking slightly hunched over, Mary was protected by the granite rampart and could avoid most of the wind and rain. Still, it was time to seek shelter. She took the massive stone stairway down to the rue Chateau-Gaillard and followed it to her hotel on the rue Sainte-Barbe, in the heart of the Old City.

The wind howled along the narrow empty streets, slamming shutters that people hadn’t had time to fasten. The few stragglers scurried along, hugging the walls, like Mary, watching out for falling slates and tiles, which such a wind could easily turn into deadly missiles.

Fortunately, the planners who rebuilt the corsair city after it was destroyed in the devastating wartime fires of 1944 capped the buildings with heavy, rustic slates secured to the rafters not by the traditional hooks, but by large-headed nails that aren’t easily pulled out.

Mary had to take shelter under an awning, because a real deluge was now pounding the town. Overwhelmed by the mass of water, the gutters spilled it onto the pavement, and the drains themselves overflowed, flooding the roadway. She only had three more streets to go before she reached the small hotel in the rue Sainte-Barbe where she had taken up residence.

Looking over the top of his reading glasses, the patron of the hotel greeted Mary with a short nod and watched as she headed upstairs. He seemed to be wondering what would possess a young woman to visit Saint-Malo in the month of November.

When Mary had disappeared up the stairway, the innkeeper leaned over his register and heaved a heavy sigh. His vacation was coming up, and he was already dreaming of white sands, palm trees, and blue seas… But all that was still a long way away. Outside, the storm had doubled in violence. Driven by the wind, the rain whipped the buildings’ facades, while inside them the north wind could be heard roaring through the alleys in spite of the windows’ double-glazing.

Emerging from this maelstrom, Mary found her room a haven of calm and warmth. Her drenched duffle coat had doubled in weight, and she hung it carefully above the washbasin so it wouldn’t drip on the carpet, then took a moment to put her things away. That done, she pushed her suitcase into the wardrobe, which creaked lugubriously when she closed its door.

Hanging on the wall was a poster for a past festival showing a group of pirates ready for a fight. It was a magnificent drawing that had illustrated Treasure Island, Robert Lewis Stevenson’s wonderful novel. In the poster’s foreground, a skeleton lay on the sandy earth. Next to it, a bareheaded man kneeled in prayer. Behind him stood five other pirates. One, wearing a red cap, was drawing a wide-bladed sabre from its scabbard. The others wore black hats. One brandished a pistol, another a rifle, a third a shovel ready to parry some unseen danger.

The artist had managed to imbue his drawing with an extraordinary sense of the tension of these men on the alert. They were facing the enemy like a pack of wolves in a time of starvation, ready to defend their prey with tooth and claw. And the prey of these wolves with human faces was gold: doubloons, ducats, pieces of eight. The very richness of the drawing’s colours evoked the mythology of treasure: red and yellow for blood and gold, the black of the hats for death.

Mary, who had approached the wall to examine the poster in more detail, took a few steps back to better admire the whole. No illustration had ever suited its book better, yet the artist wasn’t named. Was he still alive? She hoped so, because this poster, distributed by the thousands throughout France, was evidence of a great talent that might perhaps never have emerged from the shadows. Much later, she learned that the image was by the famed American painter N. C. Wyeth, who illustrated Stevenson’s book early in the 20th century.

Mary got undressed and walked into the bathroom. For a while, the sound of the shower covered that of the rain, but as she dried herself, she could again hear the furious clamour of the storm as it broke against the heavy granite walls.

She thought back to the poster. Since the 12th century, how many crews, looking more or less like the ones Wyeth had painted, had ventured from Saint-Malo’s port on makeshift boats, bounty hunters in search of the Golden Fleece? How many sails had these ancient walls seen disappear into the distance in pursuit of treasure? How many ships had come back, their decimated crews overcome with mourning and misery?

We only remember the ones who hit the jackpot, she thought, the ones who returned in glory with fabulous prizes, fat-bellied ships bulging with madras and spices to be unloaded on the quai Saint-Vincent for the greater prosperity of the entire city. Throughout its history this ship of stone, bathed on all sides by the sea, had known tumultuous times. Saint-Malo had always been a warlike, turbulent city.

The wind screamed ever louder, and, as if the sound suggested cries of anguish, Mary wondered how many quivering bodies had fallen from these ramparts and how much spurting blood had been carried to the sea by the gutters now choked with water.

Because today, Mary Lester had been called to Saint-Malo for what might well be a crime.

Chapter 2

Superintendent Rocca thought it was nothing of the sort. In fact, he looked so dubious that if you needed to illustrate a dictionary entry for “scepticism”, his face would have filled the bill perfectly.

“In that case, what did the Roch woman die of?” Mary asked him.

Rocca folded and unfolded his hands before answering. Though in his forties, he still looked the way he must have when he was twelve years old and the smartest boy in his class. His neatly combed hair was neither too long nor too short, his white shirt was impeccable, and the knot of his tie was perfectly centred in a tweed jacket he wore a little too stiffly. Rocca examined his carefully manicured fingernails. “Heart failure.” he answered in a bored tone.

“Is that all?”

“I am merely repeating the coroner’s finding.”

He nodded slightly towards a thick cardboard binder held by a canvas strap. “It’s all in there.”

“But can’t you tell me anything more?” asked Mary, irritated by Rocca’s silence, which she took for reticence.

He sighed, as if he had been asked to make an unbearable effort. The man really had a face that made you want to slap him, Mary decided. She began to think that her stay in Saint Malo wouldn’t be without a few bumps along the way.

“Tell you anything more!” he said, with a detachment tinged with condescension. “What can I say? I can’t just make things up! Madame Simone Roch was found on the big beach across from the épi de la Hoguette in early spring. On March 15th, to be exact.”

“March 15th!” exclaimed Mary. “And it’s only now that…” She didn’t complete her sentence. The young woman had died nearly eight months earlier. Mary muttered. “Well, thanks for nothing!”

The superintendent watched her with a little smirk, as if to say: Now do you understand my lack of enthusiasm?

“But if memory serves, she disappeared several days earlier?”

“You remember correctly,” said Rocca. “Madame Roch left on Saturday morning, March 4th, apparently to go jogging, and never returned.”

“When was she reported missing?”

“That same day, by her husband.”

Mary thought for a moment. “So more than a week went by between the time she disappeared and when her body was found.”

“Eleven days, to be precise,” said Rocca, proving that he knew how to count and was familiar with the contents of the file.

“The body must have been in terrible shape.”

“Horrible,” the superintendent said, squinting as if remembering how the sight had pained him. After a moment of silence, he added: “The body had spent time in the water, been carried around by the currents, battered against the rocks, and attacked by crabs and seagulls. It was in a state of advanced decomposition.”

He grimaced painfully, then lit a cigarette, perhaps hoping that Simone Roch’s mutilated ghost would disappear behind his smokescreen.

“How old was she?”

“Thirty-four,” Rocca said. “She was 34, and a very pretty woman.” He took two long drags on his cigarette, his gaze elsewhere. Simone Roch’s death really seemed to have affected him.

“Did you know her?”

He nodded in agreement, but seemed reluctant to say anything further.

“In your opinion, what did she die of?”

Rocca looked at her in surprise. “I told you, a heart attack.”

As she was looking at him in silence, he added: “The autopsy report was definite. There was no water in the lungs, so she didn’t drown.”

“Had she been raped?”

Rocca jerked upright, as if what Mary had said was completely off the wall. “Raped? Whatever gave you that idea?”

“Why not? It’s something that happens to young women who go running alone in out-of-the-way places, more often than you might think.”

As the superintendent shook his head, rejecting her hypothesis, Mary added: “A young and attractive woman in running clothes all by herself in the early morning on a deserted beach – that’s enough to give some crazy people ideas.”

Again, Rocca shook his head. “The autopsy report didn’t mention any sign of a sexual attack.”

Mary decided not to press the point. Since the superintendent kept coming back to the autopsy report, she would read it, as she would read the entire file. “So this heart attack, what would have caused it?”

Rocca shrugged. “Joggers who aren’t careful get themselves into trouble every day, when they try to do more than they are capable of.”

“So you think Madame Roch exercised too energetically and had a heart attack right on the beach.”

“Something like that, yes.” He corrected his statement. “That’s what everybody thinks. It’s the most likely hypothesis. She was running by the water’s edge and collapsed. The waves picked her body up and the ebbing tide took her out to sea.”

Mary cut in:

“And then, eleven days later, dropped her off at the very same spot where she collapsed. Hmpf!”

“That’s the conclusion we reached.”

“But it wasn’t unanimous, since her husband requested a supplementary investigation.”

“That’s his right,” said the superintendent with a pinched expression, “and he’s a man of some influence. He’s the vice president of the national notaire association, and pro tem deputy to the Assemblée Nationale. His firm is one of the most successful businesses on this coast. So he isn’t someone who is easily taken in.”

As superintendent Rocca said those words, his thin lips involuntarily tightened. The notaire must have raked him over the coals during the investigation.

Mary had opened the folder and was leafing through it. Coming to one document, she stopped. “Hey! He was old enough to be her father!”

“That’s right. Maître Roch has children who are older than his wife.”

“Had they been married for a long time?”

“Four years, I think. Maître Roch had been a widower for a dozen years when he met Simone.”

Mary looked at him, surprised by the familiarity. It was unusual for a police superintendent to refer to a victim by her first name. She closed the folder and asked: “Was there talk?”

“There’s always talk, and too much of it,” Rocca answered. “Especially under such dramatic circumstances. Before the body was discovered, rumour had it that Simone Roch had run away with some man.”

“So people knew she had a lover?”

“I didn’t say that!” he said, looking at her with irritation.

He took a deep breath, forcing himself to be calm. “I’m telling you about the gossip and rumour mongering that you find in all small towns. Don’t take it for gospel!”

Rocca shrugged his shoulders, as if he were angry at the rumour and also at the person across from him who was forcing him to mention it.

Mary, who was watching him while he said those words, lowered her eyes. The superintendent’s vehemence surprised her. He wouldn’t have spoken differently if he had been in love with Simone Roch.

“And this gossip, did it have any… foundation?”

“What do you mean?” asked Rocca, putting his palms flat on the green blotter that covered his imitation mahogany desk.

“Did she spend time with people in a way that might have fed…”

He didn’t let her finish her sentence. “Of course she spent time with people! She had men and women friends. Simone was an excellent tennis player and there wasn’t a woman who even came close to her level, so naturally she played with men.”

“Ah!” said Mary.

The superintendent gave her a dark look. “Whom she often beat!”

“So she was very athletic.”

“That’s for sure! When Roch met her, she was a mountain guide. She led people on hikes and did some climbing herself.”

“What about Maître Roch?”

“What about him?”

“Is he athletic?”

“In his way.”

“Meaning what?”

“He likes sailing.”

“Does he have a yacht?”

“Yes. In keeping with family tradition, he has a schooner at the Sablons port.”

Seeing Mary frown, Rocca asked: “Didn’t you know that we’re in an area where old traditions are still strong?”

“Sure, but that’s true all over Brittany.”

“Here more so than in other places. We even have an association of the descendants of corsairs.”

Mary smiled. “No kidding?”

“I’m not joking,” said the superintendent. “They meet in a room on the ramparts, the way they did in the good old days.”

“And Maître Roch is a member of the fraternity?”

“Of course! He’s one of the club’s most prominent members. His ancestors made their fortune at sea and greatly contributed to establishing the town’s reputation.”

“So needless to say, he has a sail boat!” Mary guessed.

“Yes, a beautiful schooner about 15 metres long, which he sails like a pro. But he certainly isn’t the type to go running along a beach, much less sweat on a tennis court.” At the thought, Rocca produced a slight smile.

“In any case, he was the one who asked for the supplementary investigation into his wife’s death…”

“Yes.” The superintendent sighed.

“You seem to regret it…”

“What’s the point? It won’t bring her back. And dying of a heart attack while jogging is an honourable death, isn’t it?”

Mary stood up. “I don’t know what you mean by that,” she said very coldly. “I’ve never understood that expression. Death is always horrible, especially when it strikes a young person who is obviously enjoying life.”

Now it was the superintendent’s turn to stand. “That isn’t what I meant to say,” he stammered. “I mean that it isn’t as hard on the family…”

She looked at him coolly. “So you think it is less painful for the widower to think that his wife died a natural death than thinking that she had been killed?”

“That’s it, exactly!” Rocca exclaimed. “You understand me, don’t you?”

“I understand what you’re saying, of course. But I’m inclined to agree with Maître Roch. The worst would be if Simone Roch had been murdered and her killer were still at large. And believe me, if this was murder, I will do everything I can to see that the culprit pays the price!”

She took the file from the table and looked down her nose at him.

“You understand me, don’t you?” he repeated.

Without making a move, Superintendent Rocca watched the door closing. For a moment he remained motionless, looking into the distance. Then he shook his head, like someone who has just awoken from a bad dream and is returning to reality. Who the hell was this woman, anyway? What nerve! None of his men would ever dare speak to him in that tone!

Someone knocked on his door, so Rocca sat down behind his desk and pretended to be looking at a folder before shouting “Come in!”

Lieutenant Maüer, who was waiting in the hallway, frowned. It wasn’t like the superintendent to yell that way, or make somebody wait before answering, for that matter. He came in.

“Monsieur le commissaire, it’s about arranging the triathlon next Sunday,” he said. “The runners are supposed to make the tour of the ramparts.”

The superintendent was looking straight ahead. Clearly, the lieutenant’s comments weren’t getting through to him. “Tell me, Maüer, did you see that girl come out of here?”

Maüer stared at his boss. It couldn’t have been that young woman who had put him in such a state! “I passed a woman in the stairs, she was wearing a beige duffle coat and had a thick file under her arm.”

“That’s her,” said Rocca. “Do you know who that was?”

Maüer raised his arms as if to say How should I know?

“Well, old man, that was Mary Lester!”

“Mary Lester,” repeated Lieutenant Maüer, who was astonished to find himself being called “old man” by the superintendent.

That kind of familiarity wasn’t the rule at the Saint-Malo police station. Superintendent Rocca never used the familiar tu with anyone, and he called everyone by their exact rank. When speaking to him, you called him “Monsieur le commissaire”, and one newcomer who had dared to call him “Chief” had been promptly put in his place. Where do you think you are? Rocca had snapped. At the wholesale fish market? On a building site? Looking woeful, the newcomer had picked himself up and given the superintendent a nickname that had stuck, and which would have made Rocca explode if he had ever heard it: “Coco”.

Coco Rocca went on. “That’s right, Mary Lester, the bird who nailed Amédéo at Lorient1 and shut down the drug ring at La Baule.2” Rocca gazed at his subordinate. “Among other things.”

“I thought Superintendent Graissac was the one who cleaned up that business,” Maüer said.

Rocca snorted with laughter. “Graissac only showed up to eat the chestnuts. Mary Lester was the one who pulled them out of the fire.”

“But she wasn’t mentioned in connection with the case,” Maüer said with surprise.

“That’s exactly what worries me,” Rocca reacted. “She did all the work and didn’t try to take any of the credit. It was the same deal at Concarneau. Lester nailed four dangerous Belgian gangsters, retrieved fifty kilos of cocaine, and then acted as if she didn’t care about it. She didn’t even take part in the interrogation!”3

“So she was the one who set the trap on that bridge at Concarneau. The four guys were picked up just as sweet as you please. I remember people talked about it as a small masterpiece of police strategy.”

“That’s the one. And the author of that masterpiece is now within our walls. You’ll see! She’s something else, I swear.”

“But what is she doing here, monsieur?”

“Investigating Simone Roch’s death.”

“I thought that the file…”

“Was closed?” Rocca asked. “Well, so did I. But it isn’t any longer. Maître Léonard Roch asked for a supplementary investigation and Lieutenant Lester is in charge of it.”

“It’s been such a long time,” Maüer exclaimed. “Lester’s going to have a lot of fun.”

Rocca looked at him thoughtfully, and Maüer returned to what had brought him in the first place. “About the triathlon, monsieur le commissaire?”

“Ah, yes, the triathlon… Who handled it last year?”

“I did, monsieur le commissaire.”

“As I recall, everything went very well?”

“Yes.”

“Well, in that case, do the same as last year, Maüer!”

1 See Les bruines de Lanester. Available in English: Drizzly days in Lanester.

2 See L’homme aux doigts bleus.

3 See Marée blanche.

Chapter 3

It had stopped raining but the wind was still strong. Strong and warm, a true west wind, loaded with humidity.

Mary crossed the place des Frères Lammenais, then the place du Pilori, and finally the vegetable marketplace. The Old City streets had names to set you dreaming: the rue du Gras Mollet – fat calf –, rue de la Corne de Cerf – deer antler – and rue de la Pie qui Boit – drunken magpie.

Over the centuries, the spirit of adventure had so impregnated these granite ramparts that neither the tons of bombs that fell on them during the last war nor the end of a millennium marked by tawdriness and mendacity had been able to dissipate it.

At the end of the 16th century, with their riches wrested from the sea and fearing neither God nor the devil, the Malouins set themselves up as an independent republic, like Venice. And ever since, the air at Saint-Malo has smelled of freedom and adventure, two words infinitely dear to Mary Lester’s heart.

She climbed the hotel stairs two at a time, threw open the door to her room, and tossed the thick case folder on the bed. Having shed her duffle coat, she undid the strap around the documents and started to peruse them.

The investigation appeared to have been carried out completely by the book. The file contained the transcript of the interrogations of the husband and of the early-morning walker who had discovered the body, one Raoul Chevallier. It also had the depositions of people who knew Simone Roch, her friends and her tennis and sailing partners. The young woman certainly did love to sail. She not only joined her husband on his schooner on weekends, but during the week went out on a sport catamaran, and even windsurfed.

Two men in particular had been questioned at length: Patrick Slimane, 33, the pro at the tennis club, and Ronald Cartridge, 29, who taught at the sailing centre. Gossip had swirled around the men as having been Simone Roch’s lovers, but both vigorously denied it.

The investigation had been conducted by Superintendent Rocca himself, assisted by Lieutenant Maüer. Maüer had minutely reconstituted Simone Roch’s movements from the moment she left the malounière at Paramé where she lived with her husband and headed for the great beach at Rochebonne.

People on their way to work had seen her running in white shorts and T-shirt with a white headband round her auburn hair. Some of them were used to seeing her, because she ran that way two or three times a week. She sometimes went along the Paramé beach as far as the Saint-Malo ramparts, then returned to the Rochebonne point. There she occasionally dove into the sea and swam for a few minutes, even in winter. She then would run back to the malounière.

Mary gave an admiring smile. Simone Roch had been seriously fit! Especially when you consider how cold the water gets on the north coast of Brittany.

She closed the file thoughtfully. The victim had behaved the way she usually did, that much had been established. Several people could attest to it, though none of them could say for sure where they had seen her for the last time.

The witnesses had been questioned two weeks after the date of her disappearance and their testimony was uncertain and tentative. So eight months later…

As Superintendent Rocca had said, the autopsy report didn’t mention water in the lungs, which proved that the victim hadn’t drowned. It seemed equally clear that she hadn’t had sexual relations before her death.

For that matter, the corpse was in such horrible shape when it was found that poor Raoul Chevallier, a pensioner who had discovered it under a pile of seaweed, had had to be hospitalised. The body was completely naked, and terribly torn up. The head was almost completely severed from the trunk, and strips of flesh had been ripped from the arms and legs. Mary closed the document, her face screwed up in disgust. Hardly surprising that it gave poor Chevallier nightmares. And to say that Rocca was calling this an “honourable” death!

“I’ll show you honourable deaths!” Mary said as she jumped off her bed. She tore down the stairs and rushed out, under the astonished eye of the innkeeper, who was seated behind his cash register reading the newspaper.

*

It was November, and the Saint-Malo bay sailing centre wasn’t exactly humming with activity. On the Dinan ramp, a neat row of catamarans forlornly awaited brave sailors.

Mary walked down the large slate slabs and approached a man in blue overalls who was working on the rigging of some aluminium masts set on sawhorses. Hearing her approach, he turned around.

“Good morning, I’m looking for Ronald Cartridge.”

“That’s me,” the man said as he put down a shackle key and an adjustable spanner. Without taking his eyes from Mary, he pulled a rag from his pocket and wiped his hands. “What’s this about?”

He spoke perfect French, but with a distinct English accent. In fact, everything about him said “British citizen”: His head of stringy, thinning hair, and his crowded, yellowish teeth identified him better than any passport.

Mary took out her I.D. card. “Police”.

The man’s face darkened, and he stuffed the rag back into his pocket. “What’s this about?” he asked again.

It seemed to Mary that Cartridge’s accent was stronger now, as if the mere word “police” unnerved him. She glanced around the deserted work area. “Is there somewhere we could talk quietly?”

He sighed and nodded towards a glass door. “The office?”

“Let’s go.”

The “office”, as Cartridge somewhat grandly called it, was a brick hut built on a slab of concrete right on the beach. Its shelves were ordinary planks casually nailed to the wall and piled with dusty files. But the place contained a metal desk with drawers, and Cartridge sat down behind it while waving his visitor towards an old stuffed armchair.

Mary sat down cautiously because the chair looked a bit shaky, a fact that Cartridge confirmed: “Be careful. I think it has one leg shorter than the others.” Then he looked at her questioningly.

“Do you run this sailing centre, Monsieur Cartridge?”

Frowning, he nodded.

“I’ve come to talk to you about the death of Madame Simone Roch.”

“That again!”

Mary couldn’t tell if his sigh was one of relief or weariness. “Did Madame Roch come to the centre regularly?”

“Yes, but I’ve already told the police all that,” said Cartridge.

“That’s right,” she said while examining her notebook. “To inspector Maüer.”

He echoed her: “That’s right, inspector Maüer.”

Then he sighed, as if he felt burdened. “Do you want to know when she rented the catamarans and windsurfers?”

“No, Monsieur Cartridge.”

The sailing instructor seemed relieved. It meant doing all that research… He cast a weary look at the folders. “It’s all written down somewhere, of course. But what a job to find it!”

Mary smiled at him. “Don’t worry, that’s not what’s involved here. I want you to tell to me about Madame Roch.”

He looked surprised, so Mary added:

“About her behaviour, what kind of a woman she was. For example, was she a good sailor?”

With his right index finger, Cartridge picked at a spot of tar on his left thumb. “I don’t know what you would mean by a “good sailor”, but she was an expert on a sport catamaran, and a very accomplished windsurfer.”

She smiled at him again. “That’s what I wanted to find out, Monsieur Cartridge. I know that you were once a long-distance ocean racer yourself.”

The man grinned widely, displaying a jumble of long teeth that would have frightened little children. He was obviously pleased that someone remembered his glorious past. Before becoming a dogsbody at the Saint-Malo sailing centre, Cartridge had been a well-known sailor and had several times finished near the top in transatlantic solo races.

“Simone came here two or three times a week,” he said.

“On a regular schedule?”

“No, just when the weather conditions suited her.”

“Meaning what?”

“Meaning when there was enough wind. She wasn’t interested in sailing in calm weather. For a catamaran, she needed a good breeze, what we call a piaule: a steady force 5 or 6. Above that, she preferred windsurfing.”

Cartridge was referring to wind strength as measured on the Beaufort sale, and was describing conditions challenging enough to keep most pleasure sailors back at the dock.

“Did she go sailing by herself?”

“No. It takes two people to sail a catamaran.”

“Who sailed with her?”

“Sometimes me, sometimes a student in the sailing school.”

“Was she gifted?”

“Oh yeah! Smooth moves were something she knew all about. She’d been a ski instructor when she was young.”

“Thirty-four years old isn’t exactly old… that’s how old she was, wasn’t it?”

“I’m not putting it well,” said Cartridge. “Of course she wasn’t old. But since most of the students here aren’t even twenty…”

She finished his sentence: “You come across as an old man.”

“There’s something to that,” he admitted with a grin. “What I wanted to say was that Simone started climbing when she was a teenager, and then she was a ski instructor at Les Arcs, in the Alps.”

“What’s the connection between skiing and sailing?”

“They both involve moving smoothly and gracefully. On a windsurfer she wasn’t afraid to go out by herself.”

“Even in heavy weather?”

“Especially in heavy weather! She had mastered the trick of making water starts long ago, so she would go out on a short board.”

“Water… whats?” Mary asked, frowning.

“In windsurfing, a water start is a technique for getting underway again from the water after you’ve fallen. You let your sail catch the wind, and it pops you upright. Not everybody’s able to do it. It takes practice, and those short boards don’t float unless they’re moving.”

Through the open doorway Mary looked at the neatly aligned, brightly coloured boards. She had trouble imagining herself doing a “water start” in a sea whipped to a froth by a force 6 wind.

“Did she mainly sail in the summer?”